Professional Documents

Culture Documents

American Economic Association

Uploaded by

saidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

American Economic Association

Uploaded by

saidCopyright:

Available Formats

American Economic Association

Price Expectations and the Phillips Curve

Author(s): Robert E. Lucas, Jr. and Leonard A. Rapping

Source: The American Economic Review, Vol. 59, No. 3 (Jun., 1969), pp. 342-350

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1808963 .

Accessed: 01/12/2013 15:17

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

American Economic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Price Expectations and the

Phillips Curve

By ROBERT E. LUCAS, JR. AND LEONARD A. RAPPING*

Until recently, there have been two main approaches,as implemenitedempiricallyby

approaches to the rationalization of the these and other authors,imply a permanent

observed negative correlationbetween the and rather discouraging tradeoff between

unemployment rate and the rate of infla- inflation and unemployment. The results

tion (the Phillips curve)'. Phillips [19] and have led to two important policy conclu-

Lipsey [8] postulated a competitive adjust- sions: first, that sustained inflation is both

ment mechanism,where the rate of change necessary and sufficient to the sustained

in money wages is negatively related to maintenance of low unemployment rates;

excess supply in the labor market, with the and, second, that policies (like wage-price

latter quantity measuredby the unemploy- guideposts) which may shift the Phillips

ment rate. A second view, expressed by curve, are an important ingredient of na-

Eckstein and WVilson[3] and Perry [17] tional economicpolicy.

emphasizes a collective bargaining mecha- Recently, several authors have sought to

nism with unemployment rates and other elaborate different theories underlying the

variables(like profitrates) measuringunion Phillips curve, emphasizingthe role of ex-

bargainingpower over (or employer resis- pectations in labor markets either in addi-

tance to) increasesin money wages.2Both tion to, or in place of, the bargainingmecha-

* The authors are associate professors at Carnegie- nisms referredto above.3These approaches,

Mellon University. They wish to thank T. W. McGuire while differing considerably in detail, all

and E. Phelps who commented on an earlier draft of suggest that the inflation-unemployment

this paper. trade-offis a short run phenomenon,or that

' Throughout this paper the term Phillips curve is

used interchangeably to refer either to a price change- sustained inflation will make no contribu-

unemployment relationship or to a money wage change- tion to the permanent lowering of unem-

unemployment relationship. ployment rates. In view of the policy impli-

2 These remarks are not intended to suggest that the

references cited contain a well articulated theory of cations drawnfrom the originalapproaches,

wage-employment determination in an economy domi- as sketched above, it is clearly crucial to

nated by collective bargaining. We have been unable to attempt to discriminateempiricallybetween

find such a theory anywhere in the literature. We have,

however, attempted to construct a rationalization of what may be called the "bargainingmech-

the Phillips curve along these lines ourselves-an at- anism approach" and the "expectations

tempt which ran into two difficulties we found insur- approach"to a theory of the Phillips curve.

mountable. First, why should "money illusion" char-

acterize the outcome of collective bargaining if the The objective of this paper is to review a

individuals and employers involved are free of it? Sec- particularversion of the "expectations ap-

ond, even if one had an adequate theory of wage deter- proach" (our own), to test this version on

mination in a single, unionized sector, what implica-

tions will this theory have for aggregate wage and em- either ambiguous or irrelevant to absol-utewage determi-

ployment determination? (This later point is developed nation. For an application of a bargaining based

more fully in [91.) In part, the union impact on aggre- Phillips curve to the entire economy (as opposed to the

gate wages depends on the wage interconnections be- manufacturing sector studied in [31,and [18]) see Tella

tween the unionized sector and the rest of the economy. and Tinsley [21].

In several recent studies, McGuire and Rapping, [11], 3 We have in mind our own previous study, [91, as

[12], [13], [14] argue that most of the evidence on well as Phelps [181, Friedman [4], Meltzer [10], and

"spillovers" from uinionized to nonunionized sectors is Mortenson [15].

342

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LUCAS AND RAPPING: THE PHILLIPS CURVE 343

United States time series for 1904-65, and wtY wt*

to use this theory as a frameworkfor isolat- WtA S

ing short and long run unemployment-

inflation trade-offs.Theory, tests, and con-

clusions are given in sections I, II, and III

respectively.

-Short-run

~{w*hed fixed}

I. An ExpectationsTheoryof

the Phillips Curve wt/Mt

In an earlierstudy4we postulated an ag- FIGURE 1

gregate labor supply function of the form:

In (Nt/Mt) the 'interpretationof all or part of measured

unemployment as an excess supply in the

(1) = iB0+ 31 Iin(Wt/Wt*) + 12 In (wg*) usual sense is precluded. We sought, then,

- 13 in (Pt*/P9), an alternativehypothesis as to what people

mean when they answer"yes"to the Census

whereNt is total man-hourssupplied,Ms is

Bureauquestion: "Areyou actively seeking

population, wt is the current real wage

work?" We hypothesized that respondents

(Wi/Pt), and wt and P* are "permanent" to this question take it to mean: "Are you

or "normal"real wages and prices respec-

seeking work at your normal wage rate?"

tively. In [91,eq. (1) is generatedby a two-

Thus we assumed that the labor force as

periodFisheriananalysis of the household's

measured by the employment survey con-

labor-leisurechoice problem,which implies

sists of employed persons plus those who

that 9, and /3 are positive, while /2 may

are searchingfor work at what they regard

have either sign. Estimates reported in [91

as their normal wage rate (or, roughly

indicate that 12 is approximatelyzero, or

equivalently, in their normal occupation).

that the long run labor supply schedule is

To define unemployment (in our sense)

approximatelyvertical. On the other hand,

more precisely, we define the normal labor

it was found that labor supply is highly

supply, N*, to be the quantity which would

responsive to changes in Wt/Wt*, the ratio

be supplied when the actual wage rate, wt,

of currentto normal wages, and to the an-

equals the anticipated normal wage, w*l,

ticipatedinflationrate, In(Pt*/Pt). Thus the

and when actual prices, Pt, equal normal

short and long run behaviorof labor supply,

prices, P* . Under these conditions, (1)

as predictedby our theory and confirmedin

becomes:

our tests, is as inidicatedin Figure 1.1

Combiningthis supplymodelwith a labor (2) In ( */Mt) -A n + /3 lit til

demand function, and assuming that labor

markets are cleared each period, one has a + (82 - 31) ItnWt- l3 (P*t/P_)

complete aggregate labor market model Subtracting(1) from (2) gives:

(once the formation of w* and P* is de-

in = 3

scribed). Completingthe model in this way, (3) (vt/lNt) In} (7ot-1/wt)

'

4Since considerable space is devoted to explaining ()+ 3 (P .1/Pt).

equation (1) in our earlier paper [9], treatment here will

be sketchy. Because In (N*lNt)-(N*-N,)IN*, the

5 An anticipated rise in the price of future goods in- left side of (3) has the dimensionsof an un-

duces, among other effects, a substitution of current employment rate, but it will differfrom the

leisure for future goods consumption-hence a decrease

in current labor supply (other prices, including the measured unemploymenitrate, Ut, for two

nominal interest rate, remaining fixed). reasons. First, teenagers and women may

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

344 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW

fail to report themselves as unemployed of (8) for 1904-65, and various subperiods,

and, secondly, N* is defined in terms of a are reported.

representative household and so does not As with the other empirical Phillips

allow for the frictional component of mea- curves, (8) implies a long run as well as a

sured unemployment. Since there is reason short run inflation-unemployment trade-off,

to think that the frictional and nonfric- with the consequent promise of a permanent

tional components of total unemployment decrease in unemployment if the economy

vary together, we assume that Ut and is willing to tolerate a sustained inflation.

In (N*/Nt) are linearly related: This long run trade-off is, however, built

inmo(8) in a transparent way by the expec-

(4) Ut = go + g lin (N*t/Nt), gO, gi > 0.

tations hypotheses (6) and (7). Thus the

Combinilng (3) and (4): reason (8) offers a long run trade-off lies in

the assumption of an unreasonable stub-

Ut = go + git3l in (wt-l/wt)

borness on the part of households: if a sus-

+ g913 III (P1/f-Pt). tained inflation policy is pursued by the

It remains only to link the unobserved, government, households following (7) will

normal wages and prices to observable, continue forever to underpredict future

actual values. In our original model we prices.

assumed that both normal variables are There is no entirely satisfactory way to

adaptively calculated by households from remedy this deficiency in the theory within

actual values, with the same reaction the framework of adaptive expectations.

parameterX, O<X < 1, or that: Any forecaster predicting future prices as a

fixed function, however complicated, of

(6) In (w*X) In

i (zet) + (1- X) In (w* 1), past prices can be systematically fooled by

and: a clever opponent manipulating the actual

series at will. But since there is little reason

(7) In (P*) X In (Pt) + (1- X) In (P* ) to believe that the government systemati-

Using standard methods to reduce the cally manipulates prices, it may be worth-

system of difference equations (5)-(7) to a while to examine adaptive schemes which,

single difference equation in Ut, we obtain :6 unlike (6) and (7), permit a short run

Phillips curve without deciding the ques-

t= Xgo - g3l In (wt/wt-i) tion of the existence of a long run curve a

(8) - gp33 In (Pt/Pt_1) priori.

Focusing on the anticipation of prices

+ (1-X) L.

rather than real wages, a natural generaliza-

The reader should note that when going tion of (7) is the hypothesis that ln(Pt*) is a

from (5) to (8) the coefficients of the wage "rational distributed lag function" of past

and price terms change sign because in (6) actual values,8 or that:

and (7) we assume an "elasticity of expec-

tations" less than unity (when current of the three variables wi, Pg and wtPg (money wages)

prices or real wages rise, suppliers anticipate implies knowledge of the rate of change of the third,

an eventual return to normalcy). Since (8) (8) can be rewritten in two other ways. In particular,

one may relate unemployment to money wage changes,

relates unemployment to the inflation rate as is more conventionally done.

(ceteris paribus) it is a Phillips curve in the 8 The term "rational distributed lag function" is

broad sense.7 In the next section, estimates from Jorgenson [6], where the word "rational" applies

to the form of the generating function of the distri-

6 See note 10. buted lag. Jorgenson shows that a distributed lag has a

I Since knowledge of the rates of chanige of any two rational generating function if and only if it can be ex-

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LUCAS AND RAPPING: THE PHILLIPS CURVE 345

In (fPt*) = boIn (Pt) + b, In (Pt-1) ward sloping short run Phillips curve is

+ + br In (Ptr)

equivalent to the condition bo< 1 (an "elas-

ticity of expectations" less than unity).

+ a, In (Pe*l) + The slope of the long run Phillips curve is

- a, In (P*L). obtained by summing the coefficients co

As in (7), we impose the condition: + - * * +Ck and dividing by one minus the

sum of the lagged unemployment terms,

(10) bo + + b + a1 + * + a, el+ * * +em.

?

For k-=0, (11) implies that there will be

so that a proportional change in all past

a long run Phillips curve if and only if there

prices would imply a change in Pt* of the

is a short run Phillips curve, both cases

same proportion.9 \We assume as well that

occurring whenever cO< . For k> 1, how-

(9) is stable.

ever, it is entirely possible that co<0 and

Equations (5), (6) and (9) form a system

simultaneously cO+ ** +Ck=0, so that

of three linear difference equations in Ut,

the slope of the long run curve is zero.

ln(P*) and ln(w*) with forcing variables

In the next section, we report estimates

in(Pt) and ln(wt), which may, using the

of the coefficients of (11) for the case k= 2,

restriction (10), be reduced to a difference

n =1, m = 2-the values which, after some

equation in Ut of the form :10

experimenting, appeared to yield the

lt = a + co0 In (Pt) + "best" results.11 Using this case as a

+ CkA Itn (Pt-k) -+ (oA Iin(Wt) maintained hypothesis, we also test the

hypotheses Co+Cl+C2=0 and do+d,= 0.

(11) + +

+d,S in (wt1n) In the testing and estimation, we assume

+ e1t7t_1 + * * - + emUt-m, that (11) is disturbed by an error term

Et, where {Et } is a sequence of independent

where Axt=xt-x_j1. The coefficient co of

identically distributed random variables

the current inflation rate in (11) is equal to

with finite variance a2 and mean 0, inde-

gfl1(bo- 1) so that the existence of a down-

pendent of contemporaneous values of

pressed in the form (9), which he calls its "final form". wt and Pt. Under these conditions, and

This usage should not be confused with "rational ex- provided (11) is stable,'2 the estimated

pectations" as defined by Muth in f16]; the two con-

cepts are unrelated.

coefficients will be consistent and asympto-

T

The formulation (9) is sufficiently general to include tically normal, and certain Chi-square

the best known expectations hypotheses. For example, tests (described in detail below) will be

to obtain (7), let bo =X and a, = 1-X.For expectations of

inflation which are adaptive on the rates of change of

approximately valid.

prices (and hence extrapolative on price levels) set

bo= 1+X) bi = -1, and a, = IA, and other ai, bj equal to II. Empirical Results.

zero. (This example also shows that one would not

wish to impose the restriction bi>O on (9)). Any con-

In this section we report tests of (8) and

vex combination of regressive (as in (7)) and extrapola- (11), on data series covering the period

tive expectations can then be formed in an obvious way. 1900-65. For the years 1900-60, the un-

10This reduction is most easily carried out by re-

writing (5), (6) and (9) in terms of current (time t)

employment series used is from Leber-

values of the variables, using the lag operator E de- gott [7, p. 512] and for 1961-65, reported

fined by Ex,=xt-1. Then to obtain (11), one multiplies census data are used [1, p. 236]. The price

both sides of (5) by [1-a,E-. . .-a8E-] [l-(1-X)E] and

substitutes from (6) and (9) to eliminate terms involving

series is the Consumer Price Index taken

wt* and P9*. Then applying (10) to the resulting expres-

sion yields (11). The parameters k, n and m of (11) are 11In terms of the parameters of (9), this case corre-

found to be k=-nax(r,s)-1, n=s, and m=s+1. Simi- sponds to r =3 and s = 1.

larly, the constants c,, di, eq are determinable functions 12 The stability of (11) follows from the assumed sta-

of bo, ... , a .... a a,,x,gi,0i and S. bility of (6) and (9).

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

346 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW

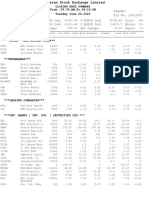

TABLE 1-ESTIMATES FOR MODEL BASED oN EQUATIONS (5), (6) AND (7).a

Variable

Time Constant Aln(Pg) Aln(wg) (Ut.1) R2(Adj) DWS

Period

1904-65 2.32 -25.28 -21.72 .822 .832 1.44

(.57)*** (5.82)*** (10.18)* (.054)***

1904-29 4.04 -10.84 -29.75 .322 .370 1.67

(.95)*** (6.84) (12.21)** (.176)

1930-45 2.50 -70.80 4.19 .818 .953 2.21

(1.40) (8.73)*** (22.45) (.063)***

1946-65 4.15 -13.80 - 4.51 .249 .180 1.73

(1.37)*** (10.23) (12.74) (.208)

1930-65 4.2 -59 -41 .80 .925 1.50

from [91 (I.0)*** (8)*** (24) (.05)***

* ) ~~~~~~.025

** one tail significanceat .01

*;** ~~~~~.005

a The unemployment rate is measured as a percentage while the Aln variables are on

the order of magnitude of .01. The effect of a one percentage point increase in the rate of

inflation on the percentage unemployment rate is found by dividing the estimated

Aln(Pt) coefficients by 100. For example, for the period 1904-29 the coefficient of Aln(Pj)

is -10.84 which is interpeted to mean that when the inflation rate goes from, say, 0 per-

cent to 1 percent, the unemployment rate falls initially by about .11 percentage points.

from [1, p. 262] and [20]. Hourly com- the results that it was fortunate that we

pensation was obtained by linking the tried it.

Lucas-Rapping [9] all economy hourly In Table 1 standard errors are given

money compensation series (1929-65) to below each coefficientestimate. Each set of

the Rees [20] series for manufacturing estimates indicates a (short and long run)

(1900-29). 13 Phillips curve with a quantitatively signi-

In Table 1 we report estimates of the ficant negative slope. Thus for example,

coefficients of (8) for the period 1904-65 leaving aside the question of statistical

(line 1), for three subperiods (lines 2-4) significance, the estimated inflation term

and roughly comparable estimates for for the period 1946-65 implies an initial

1930-65 from [9] (line 5).14 The division fall in the measuredunemployment rate of

of the period into three subperiods is about .14 percentagepoints per percentage

arbitrary. We wish to separate the post- point increasein the inflation rate. Under a

war years to obtain comparability with sustained inflation, the final impact on

the many Phillips curve studies done for unemployment is .18 per percentage point

this period. In view of the folklorereferring increase in the inflation rate [.1380/(1-

to 1929 as "the end of an era," it seemed .249)]. The real wage rate has a statisti-

another natural dividing point. Whatever cally significant effect in the predicted

the reasons for this subdivision, however, direction for the entire period and for the

we think the readerwill agree after seeing 1904-29 period, but not for the latter two

periods. There is an indication of serial

13 The data used in this paper are available upon re-

correlation in each regression.l"The Chi-

quest from the authors.

14 In [91, we measured price by the GNP deflator.

S5 We refer to the stated values of the Durbin-WVat-

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LUCAS AND RAPPING: THE PHILLIPS CURVE 347

TABLE 2-ESTIMATES FOR MODEL BASED ON EQUATIONS (5), (6) AND (9).

R2

Constant Aln(Pt) Aln(Pt-1) Aln(Pt-2) Ahl(wt) Aln(wtt-1) Ut_1 Ut-2 (Adj) DWS

Period\

1904-65 1.15 -39.16 35.36 -17.38 -11.86 26.67 1.170 - .322 .876 2.01

(.63) (6.69)*** (8.19)*** (6.84)*** (9.19) (9.52)*** (.126)*** (.123)***

1904-29 2.12 -20.09 30.32 -12.61 -34.78 - 1.32 .680 .021 .532 1.91

(1.21) (8.11)** (9.07)*** (9.11) (13.52)*** (12.92) (.227)*** (.232)

1930-45 1.98 -96.87 5.97 -24.27 18.90 11.44 .423 .374 .966 1.87

(2.08) (15.49)*** (22.13) (13.04) (22.24) (21.50) (.277) (.286)

1946-65 5.55 -12.73 -13.20 7.00 - 15.05 -10.44 .247 - .147 - .05 1.94

(3.29) (17.29) (34.20) (15.48) (22.68) (30.39) (.305) (.275)

, } one tail significance at {?

square statistic for testing the stability significance tests on the added coefficients?

of the coefficients across the three sub- Second, are the instability and serial

periods takes the value 70.9, to be com- correlation which appear in the Table 1

pared to the .005 criticalvalue (8 degreesof estimates eliminated? Third, do the esti-

freedom) of 22.0.16 Hence the hypothesis mates succeed in reconciling a downward

that the coefficients are equal in all sub- sloping short run Phillips curve with a

periods is decisively rejected. flat long run curve.

In turning to estimates for the more The estimates for the entire period, and

complicated hypothesis (11) (with k=2, to a lesser extent for the subperiods, indi-

n= 1, m= 2) reported in Table 2, we have cate clearly that the additional lagged

in mind three sets of questions. First, is inflation rates, rates of wage change, and

the additional complexity justified by unemployment rates result in a significant

improvement."7 Further, serial correlation

appears to be absent from all regressions.

son statistic. Of course, the critical values tabulated by The instability across periods is, however,

these authors in [21do not apply to stochastic difference

equations as estimated here. still present as measured by the Chi-

16 Let SSu and DF be the residual sum of squares and square statistic 64.2, to be compared to

the degrees of freedom under the maintained hypothe- the .005 critical value (16 degrees of free-

sis, let SS,, be the residual sum of squares under the null

hypothesis, and let df be the number of independent dom) of 34.3. Thus, we must discuss the

restrictions imposed by the null hypothesis. The statis- results for each period separately, rather

tic used is (DF)(SS.-SSQ/SSj2) which converges in dis- than treat the first line of Table 2 as an

tribution to a Chi-square with df degrees of freedom as

DF goes to infinity. In the subperiods, DF is as low as accurate Phillips curve for the entire

8 in some of our tests, so caveat arbiter. period. (It is fortunate that we chose

As an alternative test statistic, we conisideredthe F- arbitrarily to split the data period since

statistic based on SSn and SS.. Since the estimated

equations are stochastic difference equations, the test there is no clue in the results on the first

is also at best approximately valid and the properties line of Table 2 that the regression over the

of the latter approximation, while perhaps superior to whole period is dangerously misleading.)

the one we used, are unknown. Similar considerations

led us to use unit normal, rather than Student's tables, 17 The significance of coefficients of added variables is

to judge the significance of the estimates reported in the criterion we have uised to select the "best" of the

Tables 1 and 2. various instances of (11).

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

348 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW

In the two subperiods, 1904-29 and over the first subperiod 1904-29. In this

1930-45, indicated in Table 2 there is period, the first-period impact of an in-

evidence of a short run Phillips curve: the crease in the inflation rate is a decrease in

coefficient of Aln(Pt) in each regression is unemployment, but this initial effect is

negative and significantly different from counteracted in the second year with an

zero. On the other hand, for the period effect in the opposite direction. The third

1946-65 there is no statistical evidence of a period effect is again negative. Adding the

short run Phillips curve, but this regression price change coefficients over the three

does not improve on the comparable period terms yields a negative estimate in this

results reported in Table 1. To test for case, but this sum does not differ signifi-

the existence of a long run Phillips curve cantly from zero."8Similar remarks hold for

we consider three null hypotheses. First, the wage change coefficients over the first

the hypothesis that a sustained, con- two periods.

stant percentage rate of inflation has no The results for the second period, 1930-

long run effect on unemployment is seen, 45, indicate the presence of a long run

from (11), to require that the coefficients Phillips curve. But the results for the

of all price change variables (three in the 1946-65 period are strikingly different.

regressions reported in Table 2) add to For this period there is no evidence of a

zero: we refer to this hypothesis (in Table long run relationship, a not too surprising

3, below) as Ho. The hypothesis that the result in light of the fact that the individ-

coefficients of the lagged wage changes ual coefficients are all statistically insig-

sum to zero is termed H1. Finally, let H2 nificant in this period.

be the hypothesis that both Ho and H1 are

true. III. Conclusions

The objective of this paper has been to

TABLE 3-CHI-SQUARE TESTS articulate what we have called an expecta-

tions theory of the Phillips curve, and to

Hypothesis develop and test some of its implications.

Tested IH, H1 H2

Period Our primary emphasis has been on the

possibility, strongly suggested by our

1904-65 x2 8.360*** 1.159 9.566** theory, that the Phillips curve is a short

1904-29 x2 .095 3.051 3.819 run phenomenon, in the sense that a sus-

18 To estimate the slope of the long run Phillips curve,

1930-45 x2 23.497*** .702 24.627***

one divides the sum of the price change coefficients by

1946-65 x2 .587 .279 .942 one minus the sum of the lagged unemployment co-

efficients. This estimate can be large even in cases

01 significance where its numerator does not differ significantly from

** Rejected at

Hypothesis :ReJect

Null tIypothesls zero. Thus, for example, for the period 1904-29 this

**,, f .005 level.

estimate is - 7.96 which is smaller in absolute value

than the initial effect of -20.09 (Table 2). On the other

hand, for the periods 1930-45 and 1946-65 the long

Table 3 provides Chi-square statistics run point estimates are -567.34 and -21.03 respec-

for testing these hypothesis, for the entire tively. These estimates are larger than the initial in-

period and for each subperiod, within the flation impact as estimated by the leading inflation

term in Table 2. Of course, to the extent that the

version of (11) reported in Table 2. In view lagged unemployment rates reflect the impact of

of the instability of coefficients across forces other than lagged inflation rates, we may sub-

periods, only the subperiod results appear stantially overstate the long run effect of inflation on

unemployment rates. A discussion of this and other

to be of interest. Table 3 shows that there estimation problems in models such as ours can be found

is no evidence of a long run Phillips curve in Griliches[5].

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LUCAS AND RAPPING: THE PHILLIPS CURVE 349

tained inflation will have a temporary but Squares Regression II," Biometrika,

not a long run effect on unemployment. As 1951, 38, 159-77.

reported in the last section, our results [3] ECKSTEIN,0. AND T. WILSON,"Deter-

show (1) that our particular expectations- mination of Money Wages in American

based Phillips curve is not stable over the Industry," Quart. Jour. Econ., Aug.

1962, 76, 379-414.

three (arbitrary) subperiods of the period

[4] FRIEDMAN, M., "The Role of Monetary

1904-65, (2) that a short run Phillips Policy," Am. Econ. Rev., March 1968,

curve exists in each subperiod, although 58, 1-17.

the relationship for the most recent period, [5] GRILICHES,Z., "Distributed Lags: A

1946-65, is less statistically obvious than Survey," Econometrica, Jan. 1967, 35,

for the earlier periods, and (3) that the 16-49.

hypothesis that there is no long run Phil- [6] JORGENSON, D. W., "Rational Dis-

lips curve is accepted for the periods tributed Lag Functions," Economnetrica,

1904-29 and 1946-65, but rejected for the Jan. 1966, 34, 135-149.

period 1930-45. [7) LEBERGOTT, S., Manpower in Economitic

What is to be concluded from these Growth: The American Record Since

tests? As reported econometric models go, 1800, New York, 1964.

[8] LIPSEY, R. G., "The Relationship Be-

ours can scarcely be called successful, but

tween Unemployment and the Rate of

we think its failures are suggestive along Change of Money Wage Rates in the

several lines. First, it is clear that the exis- U.K., 1862-1957," Economica, Feb.

tence of a short run Phillips curve is con- 1960, 27, 1-31.

sistent (in practice as well as in principle) [9] LUCAS, R. E., JR. AND L. A. RAPPING,

with the absence of a long run inflation- "Real Wages, Employment and Infla-

unemployment tradeoff. Second, the ex- tion," Jour. Pol. Econ. (forthcoming).

pectations view as we have developed it [10] MELTZER, A. H., "Is Secular Inflation

appears to have promise in the sense that Likely in the U.S.," Monetary Problems

the additional explanatory variables it of the Early 1960's: Review and Approval

suggests are frequently (though by no Atlanta, 1967.

[11] McGUIRE, T. W. AND L. A. RAPPING,

means uniformly) significant. Third, and

"The Role of Market Variables and

most important, statistical Phillips curves Key Bargains in the Manufacturing

are highly unstable over time, and this Wage Determination Process," Jour.

instability is far too serious to be dismissed Pol. Econ., Oct. 1968, 78, 1015-36.

by a vacuous reference to structural [12] , "The Determination of Money

change in either 1929 or 1946. Until the Wages in American Industry: Com-

variables which are shifting these curves ment," Quart. Jour. Econ., Nov. 1967,

can be identified, and verified as important 81, 684-90.

by testing over the entire period, we see no [13] , "The Supply of Labor and

alternative to the conclusion that empiri- Manufacturing Wage Determination in

cal Phillips curves (ours included) are a the United States: An Empirical Exam-

ination," International Econ. Rev. (forth

weak foundation on which to base policy

coming).

decisions. [14] , "Interindustry Wage Change

REFERENCES Dispersion and the 'Spillover' Hypothe-

[1] Council of Economic Advisors, Eco- sis," Am. Econ. Rev., June 1966, 61,

nomic Report of the President, January 493-501.

1967, Washington 1967. [15] MORTENSON,D. T. "A Theory of Wage

[2] DURBIN, J. AND G. S. WVATSON,"Test- and Employment Dynamics," in E.

ing for Serial Correlation in Least Phelps et. al., The New Microeconomics

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

350 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW

in Employment and Inflation Theory: tween Unemployment and the Rate of

Price Wage and Employment Decisions, Change of Money Wage Rates in the

forthcoming. United Kingdom, 1861-1957," Econo-

[16] MUTH, J. F., "Rational Expectations mica, Nov. 1958, 25, 283-99.

and the Theory of Price Movements," [20] REES, A., "Patterns of Wages, Prices,

Econometrica, 1961, 29, 315-35. and Productivity," in C. Myers (ed.)

[17] PERRY, G., "The Determinants of Wage Wages, Prices, Profits and Productivity,

Rate Changes," Rev. Econ. Stud., Oct. New York 1959.

1964, 31, 287-308. [21] TELLA, A. J., AND P. A. TINSLEY, "The

[18] PHELPS, E. S., "Money Wage Dynamics Labor Market and Potential Output of

and Labor Market Equilibrium," Jour. the FRB-MIT Model: a Preliminary

Pol. Econ., Aug. 1968, 76, Part II, 687- Report," (paper presented at the Win-

711. ter, 1967 meeting of the Econometric

[19] PHILLIPS, A. W., "The Relation Be- Society).

This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 15:17:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Staggered Wage Model ExplainedDocument6 pagesStaggered Wage Model ExplainedWederson XavierNo ratings yet

- New Keynesian Models and the Expectations-Augmented Phillips CurveDocument13 pagesNew Keynesian Models and the Expectations-Augmented Phillips CurveTeddyBear20No ratings yet

- The Duration of Unemployment and Unexpected Inflation - An Empirical AnalysisDocument35 pagesThe Duration of Unemployment and Unexpected Inflation - An Empirical AnalysisAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Lec 4 AS and Phillips CurveDocument27 pagesLec 4 AS and Phillips CurveEngvalieNo ratings yet

- Theories of WagesDocument14 pagesTheories of WagesGracy RengarajNo ratings yet

- Ch. 9: Understanding InflationDocument40 pagesCh. 9: Understanding InflationfasikaNo ratings yet

- Traditional Theories of UnemploymentDocument10 pagesTraditional Theories of UnemploymentVaishnav KumarNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument36 pagesUntitledLucas OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- Hansen (1985)Document19 pagesHansen (1985)Marta Aurélia Dantas de LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Kapteyn LE2004Document21 pagesKapteyn LE2004api-3747949No ratings yet

- Hansen 1985 PDFDocument19 pagesHansen 1985 PDFadnanNo ratings yet

- Wage TheoryDocument15 pagesWage Theorysheebakbs5144100% (1)

- The Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies RevisitedDocument24 pagesThe Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies RevisitedmonoNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation - Evidence From U.S. EconomyDocument6 pagesThe Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation - Evidence From U.S. Economyabdur raufNo ratings yet

- Is The Nairu Theory A Monetarist, New Keynesian, Post Keynesian or A Marxist Theory?Document32 pagesIs The Nairu Theory A Monetarist, New Keynesian, Post Keynesian or A Marxist Theory?MilijanaNo ratings yet

- 2.8 Rober Lucas Modelo 5 Islas Some International EvidenceDocument9 pages2.8 Rober Lucas Modelo 5 Islas Some International EvidenceMatias BNo ratings yet

- Dal RopeDocument16 pagesDal RopetanunolanNo ratings yet

- Wages, Prices and EmploymentDocument9 pagesWages, Prices and Employmenttalha hasibNo ratings yet

- Summary of John Maynard Keynes's The General Theory of Employment, Interest and MoneyFrom EverandSummary of John Maynard Keynes's The General Theory of Employment, Interest and MoneyNo ratings yet

- Capítulo 2Document6 pagesCapítulo 2José David Duarte TorresNo ratings yet

- Unioersify California, Santa Barbara, CA 93104, USADocument19 pagesUnioersify California, Santa Barbara, CA 93104, USAAdem IleriNo ratings yet

- Theories of WageDocument13 pagesTheories of WageRobin TNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Wage Theories: Hrpe04 Handling Expatriate Workers in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesChapter 6 - Wage Theories: Hrpe04 Handling Expatriate Workers in The PhilippinesPat TapNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 1 - Chapter FiveDocument38 pagesMacroeconomics 1 - Chapter FiveBiruk YidnekachewNo ratings yet

- Testing Wage and Price Phillips Curves For The United StatesDocument24 pagesTesting Wage and Price Phillips Curves For The United StatesrrrrrrrrNo ratings yet

- Transferable Skills, Job Matching, and The Inefficiency of The 'Natural' Rate of UnemploymentDocument15 pagesTransferable Skills, Job Matching, and The Inefficiency of The 'Natural' Rate of UnemploymentAbdur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Conflict Inflation, Distribution, Cyclical Accumaulation and CrisesDocument19 pagesConflict Inflation, Distribution, Cyclical Accumaulation and CrisesRicardo CaffeNo ratings yet

- MIll and Wage FundDocument25 pagesMIll and Wage FundJavy De la MorenaNo ratings yet

- The Phillips Curve, Rational Expectations, and The Lucas CritiqueDocument34 pagesThe Phillips Curve, Rational Expectations, and The Lucas CritiqueAsh RayNo ratings yet

- Wage Fund TheoryDocument6 pagesWage Fund TheorySoorya LekshmiNo ratings yet

- Output and Unemployment Dynamics in Transition: April 3, 2000 Revised: January 19, 2004Document35 pagesOutput and Unemployment Dynamics in Transition: April 3, 2000 Revised: January 19, 2004marhelunNo ratings yet

- Michael Griffiths EC103H Final EssayDocument14 pagesMichael Griffiths EC103H Final Essaymunisnajmi786No ratings yet

- Weiss - 1986 - The Determination of Life Cycle Earnings A SurveyDocument38 pagesWeiss - 1986 - The Determination of Life Cycle Earnings A Surveyindifferentj0% (1)

- The Employment Ratio As An Indicator of Aggregate Demand PressureDocument9 pagesThe Employment Ratio As An Indicator of Aggregate Demand PressuretrofffNo ratings yet

- Calvo - Staggered Prices in A Utility-Maximizing FrameworkDocument16 pagesCalvo - Staggered Prices in A Utility-Maximizing Frameworkanon_78278064No ratings yet

- Economia - Robert Lucas - Some International Evidence On Output-Inflation TradeoffsDocument10 pagesEconomia - Robert Lucas - Some International Evidence On Output-Inflation Tradeoffspetroetpaulo2006No ratings yet

- Profit Sharing Vs Interest Taking in The Kaldor-Pasinetti Theory of Income and Profit and DistributionDocument14 pagesProfit Sharing Vs Interest Taking in The Kaldor-Pasinetti Theory of Income and Profit and DistributiongreatbilalNo ratings yet

- 6 Involuntary Unemployment : A. G. HinesDocument2 pages6 Involuntary Unemployment : A. G. HinesShabnam NazirNo ratings yet

- Serrano 2019 Mind The Gap TDDocument36 pagesSerrano 2019 Mind The Gap TDJhulio PrandoNo ratings yet

- Wiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsDocument20 pagesWiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id920959Document42 pagesSSRN Id920959Katitja MoleleNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy and Exchange RatesDocument37 pagesMonetary Policy and Exchange RatesJenNo ratings yet

- Subsistance TheoryDocument6 pagesSubsistance TheoryNabaneel BhuyanNo ratings yet

- Wage Determination in Rural Labour Markets: The Theory of Implicit Co-OperationDocument21 pagesWage Determination in Rural Labour Markets: The Theory of Implicit Co-OperationRohit RagNo ratings yet

- Fischer 1977Document15 pagesFischer 1977pilymayor2223No ratings yet

- Keynesian ApproachDocument15 pagesKeynesian ApproachJasmine NandaNo ratings yet

- Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage - Twentieth-Anniversary EditionFrom EverandMyth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage - Twentieth-Anniversary EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- UntitledDocument34 pagesUntitledBoton Immanuel NudewhenuNo ratings yet

- Phelps ReviewUnemployment 1992Document16 pagesPhelps ReviewUnemployment 1992pilymayor2223No ratings yet

- Purchasing Power Parity in The Long Run: Niso Philippe JorionDocument18 pagesPurchasing Power Parity in The Long Run: Niso Philippe Joriontareq tanjimNo ratings yet

- Unemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpDocument63 pagesUnemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Olivera PassiveMoney 1970Document11 pagesOlivera PassiveMoney 1970Héctor Juan RubiniNo ratings yet

- Schor, J. B. (1985) - Changes in The Cyclical Pattern of Real Wages Evidence From Nine Countries, 1955-80. The Economic Journal, 95, 452-468.Document18 pagesSchor, J. B. (1985) - Changes in The Cyclical Pattern of Real Wages Evidence From Nine Countries, 1955-80. The Economic Journal, 95, 452-468.lcr89No ratings yet

- Champernowne IS-LMDocument17 pagesChampernowne IS-LMeddieNo ratings yet

- Rent Sharing and Wages: Pedro S. MartinsDocument10 pagesRent Sharing and Wages: Pedro S. MartinsbahardajahaldaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 7th Edition Blanchard Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument27 pagesMacroeconomics 7th Edition Blanchard Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFhanhcharmainee29v100% (13)

- ECON 103 Intermediate MacroeconomicsDocument18 pagesECON 103 Intermediate MacroeconomicsRachael MutheuNo ratings yet

- Alchian InflationDocument20 pagesAlchian InflationIvan JankovicNo ratings yet

- IFRSs For SMEs in The Kenyan ContextDocument6 pagesIFRSs For SMEs in The Kenyan ContextTerrence100% (1)

- Chapter 20 - Updated (Student Version)Document36 pagesChapter 20 - Updated (Student Version)NurulNo ratings yet

- 13.1 Objective 13.1: Chapter 13 Pricing Decisions and Cost ManagementDocument43 pages13.1 Objective 13.1: Chapter 13 Pricing Decisions and Cost ManagementAlanood WaelNo ratings yet

- List Exchange CryptoDocument18 pagesList Exchange CryptoduylongpisNo ratings yet

- Module No. 2: Compound InterstDocument8 pagesModule No. 2: Compound Interstyhan borlonNo ratings yet

- Closingrates 202306junDocument20 pagesClosingrates 202306junTabrez IrfanNo ratings yet

- PPP IrpDocument29 pagesPPP IrpSam SmithNo ratings yet

- Why in Ation Is Poised To Remain ASEAN's Main Economic Concern in 2023Document31 pagesWhy in Ation Is Poised To Remain ASEAN's Main Economic Concern in 2023raditNo ratings yet

- Afar 2 Module CH 4 PDFDocument20 pagesAfar 2 Module CH 4 PDFRazmen Ramirez PintoNo ratings yet

- ECON 1001 Tutorial Sheet 2 Semester I 2020-2021Document2 pagesECON 1001 Tutorial Sheet 2 Semester I 2020-2021Ismadth2918388No ratings yet

- Wenzhou Zhongsheng Sanitary Shower ListDocument3 pagesWenzhou Zhongsheng Sanitary Shower ListCristian Jorge PradoNo ratings yet

- HERMAgreenGuide EN 01Document4 pagesHERMAgreenGuide EN 01PaulNo ratings yet

- UM20MB551-Corporate Finance: DR C Sivashanmugam Sivashanmugam@pes - EduDocument45 pagesUM20MB551-Corporate Finance: DR C Sivashanmugam Sivashanmugam@pes - EduRU ShenoyNo ratings yet

- MID TERM EXAM REVIEW: FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING FUNDAMENTALSDocument3 pagesMID TERM EXAM REVIEW: FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING FUNDAMENTALSsahittiNo ratings yet

- Problem 7 Bonds Payable - Straight Line Method Journal Entries Date Account Title & ExplanationDocument15 pagesProblem 7 Bonds Payable - Straight Line Method Journal Entries Date Account Title & ExplanationLovely Anne Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Shellmax Thermax BoilerDocument2 pagesShellmax Thermax BoilerHaribabuNo ratings yet

- Apuntes - UD 3 - THE SECONDARY SECTORDocument7 pagesApuntes - UD 3 - THE SECONDARY SECTORKhronos HistoriaNo ratings yet

- Leases: Section 15Document9 pagesLeases: Section 15Chara etangNo ratings yet

- Coi Ay 22-23Document2 pagesCoi Ay 22-23vikash pandeyNo ratings yet

- Economic System PresentationDocument19 pagesEconomic System PresentationVenkatesh NaraharisettyNo ratings yet

- Nse 20171006Document33 pagesNse 20171006BellwetherSataraNo ratings yet

- School Feeding Program Action PlanDocument2 pagesSchool Feeding Program Action PlanJazzele Longno100% (2)

- Intermediate MacroeconomicsDocument6 pagesIntermediate MacroeconomicstawandaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Affordable Urban HousingDocument76 pagesDissertation On Affordable Urban Housingflower lilyNo ratings yet

- MGT 212 - Mid 1 - LT 3 - Global ManagementDocument31 pagesMGT 212 - Mid 1 - LT 3 - Global ManagementNajmus Rahman Sakib 1931937630No ratings yet

- Shipping & Billing Address: Neha Singh: Date: 23/02/2024Document2 pagesShipping & Billing Address: Neha Singh: Date: 23/02/2024tyrainternationalNo ratings yet

- National Law University, OdishaDocument16 pagesNational Law University, OdishaTanmayNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Analysis For Financial Management 12th Edition Robert Higgins 2Document12 pagesTest Bank For Analysis For Financial Management 12th Edition Robert Higgins 2Osvaldo Laite100% (38)

- Narrative Report - Chapter 10Document4 pagesNarrative Report - Chapter 10Hazel BorboNo ratings yet

- New Directions in Federalism Studies (2010)Document126 pagesNew Directions in Federalism Studies (2010)CheesyPorkBellyNo ratings yet