Professional Documents

Culture Documents

16 - PDFsam - 426483 Chapter 4 Innovation and Creativity

Uploaded by

juliotcr2104Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

16 - PDFsam - 426483 Chapter 4 Innovation and Creativity

Uploaded by

juliotcr2104Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 4 continued

Science and creativity formulation, systematic observation, measurement and experimentation leading to

Science is not only a body of knowledge to be learned and understood, it represents a new insights. A deep understanding of the scientific method provides powerful

powerful method in identifying and solving problems with a significant creative knowledge to students, preparing them for further study in science and helping them to

component. Well-planned, structured enquiry is fundamental to science teaching as it understand applications beyond science. One simple example of enquiry-based learning

reflects the scientific method: curiosity based on existing knowledge, hypothesis in science that offers the potential for creative thinking is in Table 14, below.

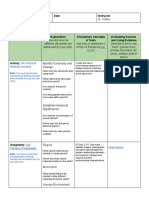

Table 14: An example of a low-tech tinkering activity: Marble Machines (Winterbottom et al, 2016, p.14)

In this activity the participants choose from a wide selection of recycled materials

and low-tech tools (for example, scissors, sticky tape, cardboard, elastic bands,

pipe cleaners) to achieve the goal of ‘getting a marble to move from the top of the

pegboard to the bottom as slowly as possible’. The imposed condition ‘as slowly as

possible’ is important. Without it, it’s too easy, and the goal is too closed.

Through their explorations, participants may engage in ‘engineering’ (for example,

working out the best materials to create a funnel), ‘making’ (for example, building

a run from cut-up tubes) and ‘tinkering’ (playfully experimenting with the different

materials as they develop their thinking and set new short-term goals).

In a science lesson, this could be a starting activity to help learners to encounter

ideas about forces and motion before any of them have been taught the ideas

theoretically. By imposing the ‘as slowly as possible’ condition, learners use intuitive

ideas about friction. They also use ideas about rotational movement, linear

movement, acceleration and velocity. When they have misconceptions about those

topics, this activity can help expose them, and enable the learners to discover that

they have misconceptions.

However, most of the time, this is not used in the context of a specific topic in

science. It is more there to foster skills, and understanding of the nature of

science, including hypothesis setting (albeit informally), testing, controlling for

Cambridge teachers exploring the idea of scientific tinkering variables and collaboration.

68 Developing the Cambridge learner attributes

Chapter 4 continued

What can we learn from the arts? Looking at and discussing artworks: The study of artworks is not necessarily limited to

Arts subjects such as art and design, music, drama and dance are often associated with art or art history lessons. Images of artworks can be used to prompt thinking in any

creativity and innovation. A broad and balanced curriculum (see Chapter 2) recognises subject area. Teachers can use carefully chosen artworks to prompt discussions and

that encouraging the arts can help students to develop their own creative voice and deeper critical thinking about a topic. Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), developed by

creative thinking skills. Studying an arts subject can also build learners’ self-confidence Yenawine (2014, p.25; see the Resources section) uses art to help learners of any age to

as they feel valued for their unique contributions and talents. When encouraging develop their visual literacy, thinking and communication skills, and is an excellent

creativity across the curriculum, it can be useful to look at the ideas and techniques resource.

that underpin the teaching of creative subjects such as art, drama and music. Journals, notebooks and sketchbooks: Keeping a notebook, sketchbook or journal is

Learner autonomy: Arts subjects can be popular with learners because of the perceived an essential part of an art and design education. All the creative skills can be practised

high level of learner choice that is involved. Learners often work on projects that they through the discipline of keeping a record of a learner’s observations, ideas, reflections

have devised themselves, according to their own interests and passions. Unique and and collections. By recording and collecting a wide range of information, a learner can

original work is particularly valued, in both informal and formal assessments. When then start to cultivate creative connections between different elements and come up

learners take control of their work in this way, their levels of intrinsic (internal) with more unique and original ideas. Notebooks and journals have been used by many

motivation tend to increase (Craft, 2005, p.56). great creators, such as the poet Lord Tennyson, who recorded fragments of thought and

then generated connected words and images which led to his poetry (Michalko, 2001,

Valuing uniqueness: Every learner’s outcome will be different in arts subjects. The idea

p.58). Charles Darwin kept detailed journals on his travels to the Galapagos Islands, and

of there being ‘no one right answer’ is deeply embedded in both the teachers’ and the

his journals contain a record of his tentative diagrams of the branching system on which

learners’ approaches. Although other subjects have more fixed subject matter, it is

he eventually based his theory of evolution. Guy Claxton (2006, p.353) recommends

important for students to learn that there is often more than one correct answer or

encouraging learners ‘to keep a commonplace book… in which they keep scraps of

more than one way to arrive at an answer.

overheard conversation, images, quotes, fleeting thoughts that didn’t go anywhere… as

Experimentation and play: In all arts subjects, there is an emphasis on most creative writers, scientists, composers do’.

experimentation and ‘play’. An art teacher will introduce a technique or material, for

example acrylic paint, and learners try it out. This may initially involve copying The value of failure: The arts, perhaps more naturally than other subjects, accept and

examples and practising. Boden (2001, cited in Ferrari, Cachia & Punie, 2009, p.19) celebrate failure as a learning opportunity and understand that it is an inherent part of

describes this as ‘exploratory creativity’, and likens it to a jazz musician learning to the creative process. As West-Knights (2017, p.49) points out: ‘One of the mainstays of

improvise based on a defined set of chords or scales. Having developed some degree of drama classes… is the notion that mistakes are OK, as long as you are trying things out.’

skill, learners can then start to experiment and push the boundaries of the material or Peer review and feedback: Peer review sessions (sometimes called group critiques) are

technique. They may choose to combine it with another technique or idea to produce commonly used in art and design as a method of informal interim assessment. Learners

something that is original to them. Boden calls this ‘combinatorial creativity’ – the present their work to small groups of their peers and receive constructive feedback. The

generation of new ideas by combining or associating existing ideas. process is carefully scaffolded by the teacher, who leads initial sessions, modelling the

There is a role for experimentation and play in all disciplines so that students learn to use types of questions and comments that are appropriate. When successful, peer

their imagination and develop engagement. As in arts subjects, this must be balanced reviewing helps learners to build independence, gain insight into their peers’ working

with, and be supportive of, skill development so that it supports students’ basic literacies. and thinking processes, and develop confidence in themselves as creative individuals.

69 Developing the Cambridge learner attributes

Chapter 4 continued

Making connections: mind mapping • Planning essays, presentations or projects. By using key words, learners can fit large

As illustrated in figure 6 on page 58, mind maps (sometimes called concept maps or amounts of information onto one page, allowing them to get an overview of a topic

spider diagrams) are a flexible and powerful tool for representing information and and to plan information strategically.

nurturing creative and critical thinking. Originally popularised and developed by Tony

• Clarifying, analysing and re-defining problems or questions. This helps learners to

Buzan in the 1970s, mind maps are designed to ‘harness the full range of cortical skills’

uncover new perspectives, to build higher-level thoughts and to develop

(Buzan, 1986, p.45) by using key words, colour, images, number, logic, rhythm and

understanding, analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

spatial awareness.

• Making connections. This supports the development of holistic and

Mind maps are essentially diagrams that visually organise information. They normally

disciplinary understanding through connecting ideas from different topics

consist of a central concept, which is expressed with a key word or short phrase. Related

or different subjects.

ideas branch off from this, spreading across the paper, which is usually in landscape

format to give the optimum space for ideas to be written. Each main branch that Mind maps are an extremely versatile and accessible approach to help visualise and

emerges from the central theme can then branch out further to related sub-sections. understand material. Many learners, including those who have dyslexia or other

learning difficulties, find mind maps very useful, and they can be used to support

The theory of semantic network models (Collins & Quillian, 1969, p.240) helps to

learning in all disciplines. Research by Park and Brannon (2013, pp.2013–2019) found

explain why mind maps are effective. Each learner has their own unique understanding

that training learners to use visual and spatial representations significantly improved

of any subject at a particular time based on their own personal associations and

their performance in mathematics, even when undertaking numerical problems.

connections. The act of creatively constructing mind maps requires students to think

Research has shown that mind mapping is more effective as a means of knowledge

hard about what they are learning and to build new connections. Learners will find it

retention and transfer than attending lectures, participating in class discussions or

easier to remember information by building their own personal representation of

reading text passages alone (Nesbit & Adesope, 2006, p.434).

understanding. It is impossible to create a mind map without active engagement and

thinking through the construct being mapped. Building up a large amount of For more information on mind maps see the references and resources at the

information on a page also encourages creativity. Learners can make connections end of this chapter.

between topics, which they may not see while studying a dense block of text. Mind

maps can be used in a number of ways including: Assessing innovation and creativity

As argued already in this chapter, the outcomes of creative processes are incorporated

• Note taking. The act of creating a mind map requires chunking of information and naturally into teaching and learning. Teachers can assess them when students complete

concepts, relating them to each other. This can be helpful both in developing

an assignment or task and have demonstrated creativity.

understanding and helping to memorise information. It makes the process of note

taking active rather than passive. At the end of a unit, a teacher might ask learners, Because creativity is a process inherently linked to reflection, it is often valuable

individually or collaboratively, to create a mind map of what they understand about to assess progress at appropriate points in the journey. This needs to be done

a topic that has been covered. Many learners find mind mapping a very useful sensitively. If learners or teachers are too critical of ideas during the ideas generation

technique when revising for exams, as the process of reformulating their notes into a phase, they may find that they dismiss all their ideas and do not have anything to

new structure is in itself a memorable activity. work with.

70 Developing the Cambridge learner attributes

Chapter 4 continued

Creativity lends itself to self-evaluation, peer evaluation, process/progress learning and training in the EU member states: Fostering creative learning and supporting

diaries (sometimes called process or progress journals), portfolio assessments, blogs, innovative teaching. European Commission Joint Research Centre.

presentations and exhibitions. As Rachel Logan, Product Manager for Art and Design at

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to

Cambridge explains: ‘We are assessing how well they have thought “around” a problem,

Achievement. London: New York Routledge.

not necessarily how well the solution works.’ She adds: ‘It’s vital that learners have

critically evaluated their outcomes, but in the end it’s mostly about the process that Kampylis, P. & Berki, E. (2014). Nurturing creative thinking. [pdf] International Academy

they went through to get there.’ of Education, UNESCO, p. 6. Available at:

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002276/227680e.pdf

Ellis and Barrs (2008, p.78) have developed a generic rubric to informally assess creative

learning. Rubrics are designed to clarify criteria and standards against which students’ Kaufman, J. C. & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of

work can be assessed. This focuses on the processes involved in creative work, including Creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1) pp. 1–12.

investigation, skills, discussion, evaluation and reflection. The rubric is intended for use Kazemi, E. (1998). Discourse that promotes conceptual understanding. Teaching

in a primary classroom, but could be adapted for any level. Children Mathematics, 4, pp. 410–414.

References Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An Overview. Theory into

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A Practice, 41(4) pp. 212–218.

case for mini-c creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, 1, 73-79 Leven, T. & R. Long. (1981). Effective Instruction. Washington, DC. Association of

Budd Rowe, M. (1986). Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Education, 37, p. 43. Michalko, M. (2001). Cracking creativity: the secrets of creative genius. California: Ten

Buzan, T. (1986). Use Your Memory: Understand Your Mind to Improve Your Memory and Speed Press.

Mental Power. UK: Pearson. Nakamura, J. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. Handbook of positive

Claxton, G. (2006). Thinking at the edge: developing soft creativity. Cambridge Journal psychology, pp. 89–105.

of Education, 36(3), pp. 351–362. Nesbit, J. & Adesope, O. (2006). Learning with concept and knowledge maps:

Collins, A. M. & Quillian, M. (1969). Retrieval time from semantic memory. A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), pp. 413–448.

Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8, pp. 240–247. Park, J. & Brannon, E. (2013). Training the Approximate Number System Improves Math

Craft, A. (2005). Creativity in Schools: Tensions and Dilemmas. UK: Routledge. Proficiency. Psychological Science, 24(10), pp.2013–2019.

Ellis, S. & Barrs, M. (2008). The assessment of Creative Learning. In: J. Sefton-Green, Richards, R. (Ed) (2007). Everyday creativity and new views of human nature:

ed., Creative Learning. [pdf] UK: Arts Council England. Available at: Psychological, social, and spiritual perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychological

https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=creative-learning- Association p.349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11595-000

sept-2008&site=45 [Accessed November 2016]. Scales, P. (2013). Teaching in the Lifelong Learning Sector. Maidenhead:

Ferrari, A., Cachia, C. & Punie, Y. (2009). Innovation and creativity in education Open University Press.

71 Developing the Cambridge learner attributes

Chapter 4 continued

Smolucha, F. (1992). A reconstruction of Vygotsky’s theory of creativity. identifying topics for further research and investigation, preparing for tests, providing

Creativity Research Journal, 5(1), 49-67. formative assessment information for teachers or preparing a research agenda for the

next unit of study.

Sternberg, R. J. (2012). The Assessment of Creativity: An Investment-based Approach.

Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), pp.3–12. Educating for Creativity: Level 1 Resource Guide

von Oech, R. (1998). A Whack on the Side of the Head: How You Can Be More Creative. www.creativeeducationfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/EFC-Level-1-

3rd ed. New York: Warner Books. FINALelectronic.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child. Soviet This guide from the Creative Education Foundation gives lots of useful tips about how

Psychology, 5(3), pp.6–18. to encourage your learners to solve problems creatively. The creative problem solving

(CPS) process is based on the Osborn-Parnes CPS model. There are descriptions of

West-Knights, I. (2017). Why are schools in China looking west for lessons brainstorming-type activities for cross-curricular projects. The ethos behind this model

in creativity? The Financial Times. Available at: is to encourage an environment in which creativity and innovation can thrive using a

https://www.ft.com/content/b215c486-e231-11e6-8405-9e5580d6e5fb [Accessed range of techniques and strategies. The authors aim to nurture creative skills which will

21 April 2017]. become an integral part of learners’ work and life in future.

Winterbottom, M., Harris, E., Xanthoudaki, M., Calcagnni, S. & De Puer, I. (2016). Buzan, T. (1996). The Mind Map book. New York, NY: Penguin.

Tinkering: A practitioner guide for developing and implementing tinkering activities. One of many publications by Tony Buzan that explores the possibilities of mind maps

Tinkering: Contemporary Education for the Innovators of Tomorrow project. and explains how they are best generated.

Resources De Bono, E. (1993). Serious Creativity: Using the Power of Lateral Thinking

Questioning to Create New Ideas. USA: Harper Business.

Although primarily aimed at a business market, this book contains very detailed

Rothstein, D. & Santana, L. (2015). Make just one change: Teach students to ask their

descriptions of how to implement Edward De Bono’s many lateral thinking tools,

own questions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

including Six Thinking Hats, Provocations, Random Input and more. There are also

This practical teachers’ guide describes the ‘question formulation technique’ as suggestions for how to run training or set up a creative thinking session, which could

developed by the authors over several years of working with learners across a range of easily be adapted for use in schools.

socio-economic backgrounds, including bilingual learners. The book goes through the

Online resources from Edward De Bono

strategies step by step and gives examples of how teachers of different subjects have

Edward De Bono’s CoRT thinking tools are described in this resource, along with many

implemented the technique.

other ideas for using questions to trigger critical and creative thinking:

Essentially, the strategy is to prompt learners’ curiosity with a ‘question focus’ which www.nsead.org/downloads/Effective_Questioning&Talk.pdf

could be an image, statement or audio-visual stimulus. Learners then create questions

Instructions and descriptions of De Bono’s CoRT thinking tools with examples:

through divergent thinking routines. They then prioritise and improve these questions

http://elearnmap.ipgkti.edu.my/resource/gkb1053/sumber/CoRT1-4.pdf

with help from their teacher. Finally, a range of possible next steps are suggested as to

what learners might do with the questions. These include ‘do-now’ activities, Simister, C. J. (2009). The Bright Stuff: Playful ways to nurture your child’s

extraordinary mind. Harlow: Prentice Hall LIFE.

72 Developing the Cambridge learner attributes

You might also like

- 15 Brain Exercises That Ensure Memory ImprovementDocument62 pages15 Brain Exercises That Ensure Memory ImprovementSir SuneNo ratings yet

- Your Delivery: How To Prepare For Your Talk How To Deliver A Great TED Talk Wrap UpDocument8 pagesYour Delivery: How To Prepare For Your Talk How To Deliver A Great TED Talk Wrap Upjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Teaching Creative Thinking Skills-Full PaperDocument22 pagesTeaching Creative Thinking Skills-Full PaperSoorej R WarrierNo ratings yet

- Understanding The SelfDocument21 pagesUnderstanding The SelfGaudencio MembrereNo ratings yet

- 9.03 Critical Thinking and Creative ThinkingDocument2 pages9.03 Critical Thinking and Creative ThinkingAishan Israel100% (1)

- 1 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages1 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr21040% (1)

- Visualcollaborationtools PDFDocument151 pagesVisualcollaborationtools PDFjuliotcr2104100% (1)

- Gestalt PrinciplesDocument23 pagesGestalt PrinciplesKaushik BoseNo ratings yet

- Domain of Learning ScienceDocument4 pagesDomain of Learning ScienceGlenda DulimNo ratings yet

- 9 Stage Planner - Where We Are in Place and Time - Grade 5Document4 pages9 Stage Planner - Where We Are in Place and Time - Grade 5Remi RajanNo ratings yet

- Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemDocument35 pagesIdentifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemMary Joy Llosa RedullaNo ratings yet

- 8 M's of TeachingDocument2 pages8 M's of TeachingNorhana Manas83% (6)

- Prelim Module Teaching Science in The Elem GradesDocument28 pagesPrelim Module Teaching Science in The Elem GradesLemuel Aying100% (3)

- LSK3701 - Notes Unit 1Document14 pagesLSK3701 - Notes Unit 1Annemarie RossouwNo ratings yet

- TCH 76220 wk6 LPDocument7 pagesTCH 76220 wk6 LPapi-307146309No ratings yet

- Teaching Science in The Secondary LevelDocument44 pagesTeaching Science in The Secondary LevelOVP ECANo ratings yet

- THE TEACHING OF SCIENCE IN THE ELEMENTARY Grade's.pptx Report TidayDocument21 pagesTHE TEACHING OF SCIENCE IN THE ELEMENTARY Grade's.pptx Report TidayJenny Grace IbardolazaNo ratings yet

- Creativity in Science:: The Heart and Soul of Science TeachingDocument3 pagesCreativity in Science:: The Heart and Soul of Science TeachingnomadNo ratings yet

- Se, Anika: Activty 1 Sc-Sci 1Document3 pagesSe, Anika: Activty 1 Sc-Sci 1Anika Gabrielle SeNo ratings yet

- An Alive' DGS Tool For Students' Cognitive DevelopmentDocument20 pagesAn Alive' DGS Tool For Students' Cognitive Developmentihsanul fuadiNo ratings yet

- AT MOOC LS Race To SpaceDocument11 pagesAT MOOC LS Race To SpaceAndreana CioruțaNo ratings yet

- Educ 535 lt3 Caldwell BDocument5 pagesEduc 535 lt3 Caldwell Bapi-390725209No ratings yet

- Using The Activity Model of Inquiry To Enhance General Chemistry Students' Understanding of Nature of ScienceDocument7 pagesUsing The Activity Model of Inquiry To Enhance General Chemistry Students' Understanding of Nature of ScienceApriliana DrastisiantiNo ratings yet

- Context Goals Beliefs and Learning MathDocument9 pagesContext Goals Beliefs and Learning MathGreySiNo ratings yet

- Ojscieadmin, Journal Manager, King & LaRocco (2006)Document13 pagesOjscieadmin, Journal Manager, King & LaRocco (2006)V VibeNo ratings yet

- Action-Research-2021-2022 (MAPEH)Document10 pagesAction-Research-2021-2022 (MAPEH)Chito AntonioNo ratings yet

- Having Fun and Learning Through Tinkering: Why It Matters To YouDocument2 pagesHaving Fun and Learning Through Tinkering: Why It Matters To YouMelissa MorgaNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Session 1 - Life & Physical Sciences ActivitiesDocument11 pagesWeek 2 - Session 1 - Life & Physical Sciences Activitiesnoura ahajriNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5: Sorting Out' - Exploring An Understanding of Freedom Through The ArtsDocument12 pagesLesson 5: Sorting Out' - Exploring An Understanding of Freedom Through The ArtsBec CNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in The Elementary Classroom: Problems and SolutionsDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking in The Elementary Classroom: Problems and SolutionsMohsin BaigNo ratings yet

- Educational Technology in The Constructivist Learning EnvironmentDocument27 pagesEducational Technology in The Constructivist Learning EnvironmentLeila Janezza ParanaqueNo ratings yet

- 3300edn Assessment 1Document5 pages3300edn Assessment 1Georgia AhernNo ratings yet

- ArtifactDocument6 pagesArtifactapi-516988940No ratings yet

- Mapping Systemic Resources in Problem SolvingDocument10 pagesMapping Systemic Resources in Problem SolvingCaro ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Final PresentationDocument13 pagesFinal Presentationapi-543425060No ratings yet

- 2009.Dehaan-essay-Teaching Creativity and Inventive Problem Solving in ScienceDocument10 pages2009.Dehaan-essay-Teaching Creativity and Inventive Problem Solving in ScienceTaufik hidayatNo ratings yet

- Forces Causing Movement CompletelessonDocument28 pagesForces Causing Movement Completelessonapi-616056306No ratings yet

- Minji CactusDocument43 pagesMinji Cactusapi-20975547No ratings yet

- Encouraging Creativity With Scientific Inquiry: Lloyd H. BarrowDocument6 pagesEncouraging Creativity With Scientific Inquiry: Lloyd H. Barrowismailia ayuzraNo ratings yet

- Orks of Art Are Good Things To Think About: Shari Tishman & Patricia Palmer Harvard Graduate School of EducationDocument34 pagesOrks of Art Are Good Things To Think About: Shari Tishman & Patricia Palmer Harvard Graduate School of EducationguillermythoNo ratings yet

- Direct Instruction Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesDirect Instruction Lesson Plan Templateapi-532300724No ratings yet

- LOQ-model-of-science-teaching PendukungDocument8 pagesLOQ-model-of-science-teaching Pendukungkamilah kurniaNo ratings yet

- Creating A Classroom Community: Inquiry and Dialogue: Week 8 Lecture Summary 3 March 2008Document24 pagesCreating A Classroom Community: Inquiry and Dialogue: Week 8 Lecture Summary 3 March 2008Ethan Jimuel OhcidnalNo ratings yet

- The Interpretation Construction Design Model For Teaching Science and Its Applications To Internet-Based Instruction in TaiwanDocument15 pagesThe Interpretation Construction Design Model For Teaching Science and Its Applications To Internet-Based Instruction in TaiwanALL MoViESNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Inventions PDFDocument5 pagesEgyptian Inventions PDFapi-453830123No ratings yet

- Improving Creative Thinking Ability of Class X Students Public High School 59 Jakarta Through Guided Inquiry Learning ModelDocument7 pagesImproving Creative Thinking Ability of Class X Students Public High School 59 Jakarta Through Guided Inquiry Learning ModelRini Endwiniksfitri Rara AlwanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum - Science Stage 4 - Lesson PlansDocument28 pagesCurriculum - Science Stage 4 - Lesson Plansapi-435765102No ratings yet

- Inquiry in Science and in Classrooms Inquiry and The National Science Education StandardsDocument13 pagesInquiry in Science and in Classrooms Inquiry and The National Science Education Standardsapi-632830949No ratings yet

- ACHG300 Assignment 1Document25 pagesACHG300 Assignment 1siyabongakhuzwayo3No ratings yet

- Deep Knowledge & Higher Order ThinkingDocument4 pagesDeep Knowledge & Higher Order Thinkingapi-351478197No ratings yet

- Bubble Planner How The World Works LiteracyDocument6 pagesBubble Planner How The World Works LiteracyasimaNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 The Science Framework in The K To 12Document2 pagesActivity 2 The Science Framework in The K To 12WagayanNo ratings yet

- Original Lesson Plan With CommentsDocument11 pagesOriginal Lesson Plan With CommentsAllison Lynné ArcherNo ratings yet

- Ej 777786Document8 pagesEj 777786Danny SilungweNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Science, A Constructionist Approach To Science Literacy in Middle SchoolDocument6 pagesProblem-Based Science, A Constructionist Approach To Science Literacy in Middle SchoolJeanOscorimaCelisNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving in Science Learning - Some Important PDFDocument5 pagesProblem Solving in Science Learning - Some Important PDFgiyonoNo ratings yet

- Creativity Graphic OrganizerDocument3 pagesCreativity Graphic Organizerapi-489701601No ratings yet

- Drawing From Life: January 2016Document25 pagesDrawing From Life: January 2016Matteo CarusoNo ratings yet

- The Object of Their Attention: Behold The Darning EggDocument4 pagesThe Object of Their Attention: Behold The Darning EggValentina DimitrovaNo ratings yet

- Peter PetrakisDocument13 pagesPeter PetrakisStephen RowntreeNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Lesson PencilDocument8 pagesSocial Studies Lesson Pencilapi-384482519No ratings yet

- Exploring Theory PaperDocument8 pagesExploring Theory Paperapi-308088258No ratings yet

- Sparks-Langer and Colton - Synthesis On Research On Teacher Reflective ThinkingDocument9 pagesSparks-Langer and Colton - Synthesis On Research On Teacher Reflective Thinkingophelia elisa novitaNo ratings yet

- Name: Sydney Bull Grade: Kindergarten/ Grade 1 Draft Unit Planning TemplateDocument6 pagesName: Sydney Bull Grade: Kindergarten/ Grade 1 Draft Unit Planning Templateapi-339858952No ratings yet

- Behaviorism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism: Klara Ndoni Grupi B Pranuar: Ped. Gerda SulaDocument11 pagesBehaviorism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism: Klara Ndoni Grupi B Pranuar: Ped. Gerda SulaClara Melissa BlueNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Style ValuesDocument13 pagesCognitive Style ValuesDAYELIS DUPERLY MADURO RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Constructivism: The Associated Names of This TheoryDocument11 pagesConstructivism: The Associated Names of This TheoryFitri MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Innovation and Creativity: Lev Vygotsky, 1930/1967, Cited in Smolucha, 1992, P. 54Document5 pagesChapter 4: Innovation and Creativity: Lev Vygotsky, 1930/1967, Cited in Smolucha, 1992, P. 54juliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 11 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-FreeDocument5 pages11 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-Freejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 21 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-FreeDocument5 pages21 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-Freejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 16 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-FreeDocument5 pages16 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-Freejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 6 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-FreeDocument5 pages6 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-Freejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Continued: and Developing Practice. London: RoutledgefalmerDocument2 pagesChapter 4 Continued: and Developing Practice. London: Routledgefalmerjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Graphic Facilitation: Simplify Complexity and Make The Invisible VisibleDocument5 pagesGraphic Facilitation: Simplify Complexity and Make The Invisible Visiblejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 26 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-FreeDocument3 pages26 PDFsam Pdfcoffee - Com Visuals-Conversion01-Pdf-Freejuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- My First BoardDocument1 pageMy First Boardjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Forget About YourselfDocument8 pagesForget About Yourselfjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 41 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages41 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Use Appropriate Charts: Akash Karia Mikebaird CompfightDocument8 pagesUse Appropriate Charts: Akash Karia Mikebaird Compfightjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 61 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages61 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 21 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages21 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 81 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages81 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104100% (1)

- 101 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages101 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 41 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages41 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 101 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages101 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 141 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages141 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 61 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages61 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- 81 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages81 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104100% (1)

- 21 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For BusinessDocument20 pages21 - PDFsam - The Idea Generator Tools For Businessjuliotcr2104No ratings yet

- Cognitive Development: Answer: CDocument4 pagesCognitive Development: Answer: CAli Nawaz AyubiNo ratings yet

- Career Satisfaction Theory Final2Document17 pagesCareer Satisfaction Theory Final2Mary Apple Danielle CanaresNo ratings yet

- The Functions and Theories of ArtDocument4 pagesThe Functions and Theories of ArtTitus NoxiusNo ratings yet

- Memory PretestDocument2 pagesMemory Pretestapi-301592360No ratings yet

- Noyd - Writing Good Learning GoalsDocument8 pagesNoyd - Writing Good Learning GoalsRob HuberNo ratings yet

- Intro. To Political TheoriesDocument3 pagesIntro. To Political TheoriesAilene SimanganNo ratings yet

- Cuadro Comparativo Methods 2ND LG AcquisitionDocument18 pagesCuadro Comparativo Methods 2ND LG AcquisitionBraian Maximiliano GarcésNo ratings yet

- CreativityDocument10 pagesCreativitySamithaDYNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory Dollard and MillerDocument4 pagesAttachment Theory Dollard and MillerJoshua GerarmanNo ratings yet

- Understand Yourself PDFDocument3 pagesUnderstand Yourself PDFgeethangalinvaanavinothanthamizNo ratings yet

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 1, 2007Document151 pagesProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 1, 2007Scientia Socialis, Ltd.No ratings yet

- Learning Styles مترجمDocument26 pagesLearning Styles مترجمzeyad.mohd20No ratings yet

- Language Acquisition: How Do We Learn?Document64 pagesLanguage Acquisition: How Do We Learn?Nel MachNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Why Improving and Assessing Executive Functions - Diamond PDFDocument36 pages2016 - Why Improving and Assessing Executive Functions - Diamond PDFMADDAMNo ratings yet

- Cog Ass Syllabus-2018 Fall - StuDocument5 pagesCog Ass Syllabus-2018 Fall - StuNESLİHAN ORALNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2 Art Appreciation - Imagination, Creativity, ExpressionDocument10 pagesLESSON 2 Art Appreciation - Imagination, Creativity, ExpressionBarry AllenNo ratings yet

- Ican PPTDocument40 pagesIcan PPTRajeshNo ratings yet

- PD - CRS Evaluare Parkinson PDFDocument72 pagesPD - CRS Evaluare Parkinson PDFAngelica MarinNo ratings yet

- While Change Blindness Is Explained by A Variety oDocument2 pagesWhile Change Blindness Is Explained by A Variety oHedrene TolentinoNo ratings yet

- HTTPS:WWW - Gla.ac - uk:Media:Media 846944 SMXXDocument3 pagesHTTPS:WWW - Gla.ac - uk:Media:Media 846944 SMXXValeria RochaNo ratings yet

- 0.7 PART 7 - Major Theories of SLADocument29 pages0.7 PART 7 - Major Theories of SLASehamengli FalasouNo ratings yet

- Dark PsychologyDocument61 pagesDark PsychologyStephenOnahNo ratings yet

- Animal Behavior-Fly Away Home - GATEDocument2 pagesAnimal Behavior-Fly Away Home - GATEJonas WelliverNo ratings yet

- FS 2 Experiencing The Teaching Learning ProcessDocument27 pagesFS 2 Experiencing The Teaching Learning ProcessHannahclaire DelacruzNo ratings yet

- JOHN LOCKE (1632-1704) Man and The State: Sarah Mae B. ZamoraDocument9 pagesJOHN LOCKE (1632-1704) Man and The State: Sarah Mae B. ZamoraSarah ZamoraNo ratings yet