Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Maya Carved Shell Plaque From Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico. Comparative Study

Uploaded by

Numismática&Banderas&Biografías ErickCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Maya Carved Shell Plaque From Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico. Comparative Study

Uploaded by

Numismática&Banderas&Biografías ErickCopyright:

Available Formats

A MAYA CARVED SHELL PLAQUE FROM TULA, HIDALGO, MEXICO: Comparative study

Author(s): Donald McVicker and Joel W. Palka

Source: Ancient Mesoamerica , Fall 2001, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Fall 2001), pp. 175-197

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26308002

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26308002?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Ancient Mesoamerica

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Mesoameñca, 12 (2001), 175-197

Copyright © 2001 Cambridge University Press. Printed in the U.S.A.

A MAYA CARVED SHELL PLAQUE FROM TULA,

HIDALGO, MEXICO

Comparative study

Donald McVickera,c and Joel W. Palkab,c

department of Sociology and Anthropology, North Central College, Naperville, IL 60566, USA

bDepartment of Anthropology/Latin American and Latino Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60607, USA

department of Anthropology, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605, USA

Abstract

In the early 1880s, a finely carved Maya shell picture plaque was found at the Toltec capital of Tula, central Mexico, and was

subsequently acquired by The Field Museum in Chicago. The shell was probably re-carved in the Terminal Classic period and

depicts a seated lord with associated Maya hieroglyphs on the front and back. Here the iconography and glyphic text of this unique

artifact are examined, the species and habitat of the shell are described, and its archaeological and social context are interpreted.

The Tula plaque is then compared with Maya carved jade picture plaques of similar size and design that were widely distributed

throughout Mesoamerica, but were later concentrated in the sacred cenote at Chichen Itza. It is concluded that during the Late

Classic period, these plaques played an important role in establishing contact between Maya lords and their counterparts

representing peripheral and non-Maya domains. The picture plaques may have been elite Maya gifts establishing royal alliances

with non-local polities and may have become prestige objects used in caches and termination rituals.

One of the more significant pieces in the Field Museum of Natural 950-1250. These dates fall within generally accepted Mesoamer

History's Mesoamerican collection is a small carved shell plaque ican chronological parameters (cf. Wren and Schmidt 1991).

(9.5 X 5.8 X 0.8 cm) from Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico (no. 95075).1

The low-relief image depicts a seated Maya lord looking to the HISTORY

viewer's left and wearing an elaborate, long-snouted reptilian head

The first published notice of the carved shell plaque appeared in

dress lacking a lower jaw. A band of hieroglyphs is incised on the

Charnay's 1885 publication Les anciennes villes du Nouveau

reverse side (Figures 2, 3, 6, and 7). Its closest analogues are the

Monde. On page 74, Charnay illustrates the carved shell (in a

well-known Late Classic Maya jade "picture plaques" depicting

reversed drawing), labels it, and makes the following comments:

seated lords. This plaque is significant not only because of its

aesthetic qualities, but also because it is the only known indisput

Parmi les autres antiquités que j"ai recueillies á Tula, figure une

ably Classic Maya-style piece found at Toltec Tula. How its dis

large coquille de nacre sculptée, qui représente un chef toltéque

covery at Tula may effect our understanding of the interaction

avec tous ses attributs et qui ressemable aux sculptures de la

between Maya and Toltec is discussed later. pierre de Tizoc a Mexico, mais mieux encore á certains bas

The image on the Tula plaque can be compared with other reliefs de Palenque et d'Ocosingo, dans l'État du Chiapas.

Mesoamerican depictions of seated lordly figures dating from the

Classic to Early Postclassic periods (for the sites discussed in this Among the other antiquities that I collected at Tula was [fig

paper, see Figure 1). For the purposes of this article, the Maya ures] a large sculpted shell of nacre [mother-of-pearl], which

Late Classic period will be dated ca. a.d. 600-800. In the descrip represents a Toltec chief with all his attributes and which re

tions that follow, a Terminal Classic period will be dated ca. a.d. sembles the sculptures of the Tizoc stone in Mexico, but better

800-950, and the Early Postclassic period will be dated ca. a.d. still certain bas-reliefs of Palenque and Ocosingo in the state of

Chiapas.

In the English translation (Charnay 1887:97), the piece is again

1 Before he retired as a curator of anthropology at The Field Museum, illustrated and labeled "warrior's profile, found at Tula," but his

Donald Collier discussed this plaque with Donald McVicker. Collier sug comments are abbreviated:

gested that an invertebrate biologist should be consulted for identification

of the shell itself; that a history of the piece should be written; that the

remaining Maya hieroglyphic inscription should be translated; and that its Among the objects which we found at Tula is a large curiously

provenance from Tula should be evaluated. The publication of this paper carved shell of mother-of-pearl; the carving recalls Tizoc's stone

fulfills a long-standing obligation and is dedicated to Collier. and notably the bas-reliefs at Palenque and Ocosingo in Chiapas.

175

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

176 McVicker and Palka

Yucatan

Huasteca

El Tajin

Misantla

. Teotihuacan

Tenochtitlan .Veracruz

• Cacaxtla

Xochicalco

Mexico

Michoacan * ! Peten .*

Piedras Negras, Tikal

. Monte Albdn Tonina . ~^.La Pasadita •'

Simojovel"* Bonampak Yaxchilan j

Chiapas Dos^^^^Machaquild

■'""1 fl "KJ

Nebaj T3

* San Augustin^z .

^

r<?

<//Y

^

0 160 km

u i

Figure I. Map of Mesoamerica, with s

ularly

In neither publication is theshaped fragmen

hieroglyphic in

referred to (Figure 2a).

notes that "[t] he work

The object next appears in Peñafiel's

Zapotecan" m

and that "th

Monumentos del arte Mexicana

with antiguo on

the inscription (

plates on page 169, the shell

nized theand its inscript

significance o

plate and is simply the

described as "Relieve

feature most dese in

del Sr. D. E. Macotela [Relief in Mother-of-

[mispaginated 10]). He

Mr. D. E. Macotela]. In

had 1899, Peñafiel

published, then (19

"p

lustrates the shell, but not the inscription,

fortunately, despite the

were published upside

Starr

Relieve Grabado en Nacar, Dereached two

Fotografía "st

Direc

escritura parecida a la Maya,

form encontrado

characters en las

were

Tula, estado de Hidalgo.

far outside of the reco

ment of the city—or (

Carved relief in mother-of-pearl

nected Tula,directly

at thefrom

time

The reverse has writing similar to

presumably that of the

to the Ea

the planted fields of Tula, state of Hidalgo.

conclusion deserves co

tween Chichen Itza and Tula is still a matter of considerable debate.

This is the only text Inknown that

1905 Starr sold his Mexican collectionsgives

to the Field Mu any

the shell being found

seum. Oninthe backthe cultivated

of accession fie

card no. 95075 for the Tula plaque,

Sometime after the publication

the following comments were typed: of Monum

tained the plaque, for in 1898, Frederick S

thropology at the University of Chicago,

This is one of the finest and most beautiful specimens of shell

from Peñafiel (Frederick Starr Field Noteboo

carving ever found in Mexico. It is engraved on a haliotis [sic]

cago Libraries, Special Collections 17:53),

shell (abalone). The figure is of very characteristic Mayan tech

the first Southern Baptist missionary in Tol

nique and art and probably represents a warrior with a great

his agent. Starr published his

plumed headdress. . . . The prized

object was new

evidently originally quad

ceedings of the Davenport Academy

rilateral and rectangular and was subsequently trimmed ofsmaller, Sci

110 [mispaginated 10]). For

parts of the figure unknown

being cut rea

away in the process. The shell has

identification of the shell

also flaked awayfrom mother-of-

in places. It was perforated in several places

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 177

Figure

Figure

2. Nineteenth-century

2. Nineteenth-century

renderings of the Tula plaque, (a) Charnay re

(1887:97

(1887:97

[image reversed]];

[image

[b] Penafiel [1890:1:169,

reversed]];

Plate 80 [inscription [b] Pe

upside

upside

down]]. down]].

warrior's profile, found at tula.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

178 McVicker and Palka

Figure 3. Frederic

plaque. (Courtesy

ence,Davenport, IA

photo inscription (

(

[mispaginated 10)),

10]],

so that it could be worn

Baja as an

Californiaorna

w

a band of hieroglyphic

the symbols

authors wh

ques

dric, but which are

been difficult

re-carvedof i

o

inscription has ever,

also been cut

discuss away

the

Most recently.

The fact that the specimen,

trate the while

shell in

in the old Toltec city of Tula raise

fortunately, it is

known that from about 1200 to 13

the "Leaning Lor

course between the Toltec cities

ural jades as "som

cities of Yucatan and it is probabl

from Yucatan to

to the

Tula at

cult

this

of Q

perio

between the car

Donald Collier,

plaques

curator

(1998:20

at The

ments were by J. Eric S. Thom

parallel those written

ANALYSIS by Starr.

Contemporary interest in th

Scheie Although the Miller

Mary and facts surrounding the discovery

when of the Tula plaque in th

then a sementera

displayed in will probably

the never be known,

museum four avenues are avail

hibition "The able

Bloodto further our knowledge

of of the shell, its chronologicaj posi

Kings."

(Scheie and Miller 1986)

tion, and its place of manufacture the

and function: (1) a reconsiderationpie

ornament") under the

of the species and habitat section

of the shell; (2) a reading of the glyphs; o

fied (3) stylistic

(following Theanalysis and iconographic

Field interpretation; Muse

and (4) com

the authors goparison

on with jade to

picture plaques and distributional analysis.

speculate t

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 179

Engraved bas-relief Like mother-of-pearl

or carved the Tula plaque, shell

somep

human figures are mention the

extraordinarily kind

rare of object

in the archaeoa

of Mesoamerica. Only a (cf.

few Houston

specimenset have

al. 1989).

been Fo

id

appear to be comparable to The Field

illustrated Museum

in Figure she

5b, the

most of these appear to seated

be figure

incised refers

rather thanto thron

carved.

shell is illustrated by Covarrubias

A third class (1957:Plate LII

of carved/inc

nience is given, nor is its

by current location

"Huastec" gorgetsspecifie

(Beyer

The second incised shell is illustrated

northern by Hellmut

Gulf Coast Late Po

Figure 547). Again, no widespread

location or atprovenience is

the time of th

third, less comparable incised

and theirexample, described

iconography is notas

Finally, from

pearl shell plaque from Simojovel, Panaba in

is illustrated onthp

Second Palenque Round TablePeninsula, near the

(Robertson coastal co

1976:61, 6

The full figure in profile with

bearsa miniature

little resemblance

palace scene

to

et al. 1998:590-591,

sented on the plaques mentioned earlier. Number

approximates

A second category of carved shell thatthe may style of t

be relate

lord's facial produced

ferred to as a conch-shell "silhouette," featuresusing

are m a

ing and incising technique Late/Teminal

(Figure 5b). Classic repre

Two remarka

carved

are from the Bliss Collection on an alabaster

(Lothrop (tecal

et al. 1957:25

[cat. no. 104]), and one is illustrated

plaque from in Schmidt

a cache et

at Uxm

91, Number 289). The Two

latter published

example worked

is said to be shell

from

in Mexico Museo represent

Nacional de at

the the

Antropología.

Classic Maya sh T

Pomona,

lection examples at Dumbarton OaksBelize (Digby

also are 1972

said to ha

in the state of Campeche depicts two

with six kneeling

Jaina figure

figurines in a

ered with an inverted Late

flares.

Classic

Thenubbin

Early Classic

tripod imag

poly

A final example of this twins

secondatcategory is inof

the portals the Mu

Xibal

American Indian (MAI) collections (Fagan

Kerr 1998:112, 1977:351).

Plate 38) is d

accession records it is mountain cave."

described simply as "shell carvin

Maya man with elaborate feather who headdress and a

spool . . . [Once] entirely inlaid with precious stones

Shell Identification and Current Condition

uted to Palenque, undoubtedly on stylistic grounds.

cept for the posture andRiidiger

gesture,Bieler (Chair of it displays

Zoology, few

Field Museum) and Linda Nicho of th

attributes of either the las

Tula plaque or the jade

(Adjunct Curator, Anthropology) have looked at the Tula shellpictur

cussed later. Clemency and Coggins (personal

believe that it is most likely a pearl mussel communi

(Pinctada). Be

proposes that, except for causethe obvious

of its size, curvature, surface nose

morphology,bridge,

and iridescent its

suggests Xochicalco rather than

coloration, Bieler isPalenque, and

convinced that the specimen that

derives from a it m

carved in the states of Campeche or Yucatan.

large-shelled species of the bivalve genus Pinctada, not a member

These shell silhouettes belong to Haliotis.

of the gastropod genus a different traditio

Because the Atlantic-Caribbean

Tula plaque and related jade

species do picture plaques,

not reach this size and thickness, the likely and their

origin of the

appears to be limited to Campeche and adjacent

shell is in the Indo-Pacific region. There, three nominal Pinctada are

the posture of the figures is the

species reach similar, much

size exhibited by this fragment (P.of maxima,theP. ico

not. The profiles are often non-Classic

margaritifera, Maya,

and P. mazatlanica). Bieler suspects that theandshell the

resemble typical

plaque wasthose

ceramic of

Jaina-style

made from the Pinctada mazatlanica (Hanley 1856), afigu

1997). Furthermore,

they relatively

are commoncarved from conch

bivalve ranging in the eastern rather

Pacific from

of-pearl and once were lowerinlayed

California through thewith "precious"

Gulf of California and south to Peru. s

1986:156, Figure 129). This

(The othertradition may

two Pinctada species mentioned be associa

are Indo-western Pa

Chontal ("Putún") Mayacificinhabiting

forms.) Such a wide-rangingwestern coastal

species offers little data for a

the Terminal Classic period.3

pattern of procurement. In fact, Feinman and Nicholas (2000:127,

Figure 6) found that Pinctada was the most commonly worked

shell in Ejutla, accounting for more than 65 percent of the marine

2 Etching lines on the surface of a shell is the most frequent style of

shell assemblage.4 It is clear that the shell is not Haliotis (abalo

incising. On nacreous shells, exterior lines may cut through to the mother

of-pearl underneath. Carved shells are done in bas-relief, with portionsne);

of why Starr came to that conclusion is unknown.

the material removed. The Tula plaque is unusual in that the inside of the Apparently the shell was re-carved, perhaps more than once.

shell has been carved directly into the mother-of-pearl.

A remarkable carved and incised silhouette shell is on loan to the Proskouriakoff's (1974:x) analysis of comparable jade plaques

indicated that this was a common occurrence. When the seated

Brooklyn Museum of Art (TL 1991.109.2a,b). The detailed image of the

person

leaning lord is etched with an extraordinary fine line; his appearance is is viewed and the shell is turned around, the text is upside

"classic," and he leans against a bar resting on his knee carved with seven

glyphs. Several edges of this plaque appear smoke-smudged, and drilled

depressions probably held inlays. The lord once wore a detachable head4 Despite years of extensive work on shell from the Valley of Oaxaca,

Feinman and Nicholas (1993, 2000) have not reported a single carved

dress (now missing). The shell has not been identified but is flat and pale

ivory in color. It may be conch. The back of the shell shows clear vertical

shell comparable to the Tula plaque. However, jade picture plaques dis

ribbing. This piece has not been published. Photographs are not available,

cussed in the text have been found in the Valley and at Monte Alban (Caso

and no additional information is to be had at this time. 1965).

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

180 McVicker and Palka

Figure 4. Term

(a) Xochicalco-st

cf. Batres 1902

Serpents, detail

Great Britain an

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 181

Figure 5. Maya incised shell-plaques, (a] Incised-shell "gorge

Dumbarton Oaks silhouette-carved conch-shell plaque (cour

DC).

down. This is not the usual Maya or Mesoamerican presentation was it reshaped without regard to the inscription? However, be

of image and text on jades, shell, or other portable ornaments. The cause it is likely that the plaque was never intended to be worn as

texts are usually matched with the orientation of the image. How a pendant, the orientation of the text may not have been essential.

ever, the pendant holes on the shell do not allow for the hanging of If it was a talisman possessed by foreigners who were unfamiliar

either the text or the image right side up. It is conceivable that the with Maya texts, the inscription itself may have been of little

unfinished perforation near the headdress of the image indicates significance.

that the final carvers tried to have it suspended with the image

right side up but then did not complete the work. However, many

Hieroglyphs

of these perforations may not have been intended for suspension

at all, but for inlays. The band of hieroglyphs on the back of the Tula plaque is largely

Clearly, the Tula shell was larger originally; sections have been phonetic and difficult to decipher. This may be due to the shell's

broken or sliced off on at least three sides. Part of the figure's relatively late chronological placement and the possibility that the

feathered headdress and neck pendant have exfoliated since Char hieroglyphs represent a regional Mayan dialect (perhaps Chontal

nay's drawings and Starr's drawings and photographs. The glyphs or Yucatec) that is not commonly found in the Classic Period

on the back have also been damaged, especially the "smoke/fire" inscriptions of the southern lowlands. Perhaps further compari

glyph (third from the left), which is almost completely erased sons with hieroglyphs from Classic to Postclassic times will help

now. How much damage to the original piece may have been the provide a decipherment of the Tula plaque's text and knowledge

result of 800 to 900 years in a field, and how much to deliberate of its temporal and spatial provenience. What is also interesting

reshaping, may never be known. When the piece was re-carved, about the hieroglyphs of the shell's reverse side is that they have

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

182 McVicker and Palka

raised glyphs "type of shell" or

features "name of carved shell";

and feweru huuch (his

that shell); "person's/owner's

shell the

was name." ground o

from the Although rare, glyphs do appear on the back of various jade

background. In

glyphs on objects, including

the plaques from the Cenote of Sacrifice

reverse (Prosk

of t

of the shell ouriakoff

is1974:207-210)

turned (Figure 13c). They also appear on the

arou

the text. picture plaque from the El Castillo cache (Carnegie Institution

An initial 1937:113), naming a ruler from Calakmul.

reading and cata

text on the back of the pla

1) eroded; 2) T692(854):19(or 24?):30/ pumu(wa) or puli STYLE AND ICONOGRAPHY

(wa); 3) T122 [smoke scrolls]:T669:102(or 103?) K'AK'(ki?

or ta'?); 4)T74(or 184?): 114:62(?):606 (or669?):607(?)/maxa The Tula shell plaque most likely dates to the Late Classic or

? ta or ho (or perhaps a version of K'INICH [mahkina]) Terminal Classic period and was perhaps re-carved as late as the

Early Postclassic period. The seated male lord on the front of the

This text may list the names and titles of a Maya noble (nobles Tula shell is depicted in low relief (1-3 mm.) (Figures 6a and 7a).

often used "fire" in their epithets) or it may refer to a sacred He wears a "jawless zoomorph" headdress (cf. Scheie and Miller

1986:78, 89, Plate 6) with feathered fans on its reptilian forehead

burning or ceremonial fire. The second glyph from the left may

read pum or pumuuw; if the affix is mu and not li, which Moran and muzzle. Long, beaded headdress feathers reach the noble's

(1935 [ 1625]:61) lists as pum 'sign/exhale, pursing the lips.' Can waist, and he wears wristlets and anklets of beads; earplugs with

this be taken as a description of someone smoking or blowing a tubular beads; and a beaded, mirror-shaped necklace pendant with

flame? Because very few Mayan dictionaries have entries for pum, three dangling bead tassels. These types of round beaded pen

and the structure of these hieroglyphs do not follow other glyphic

dants, and particularly the one worn by the figure on the Tula

examples of verbs meaing "burn" in Classic Maya texts (Stephen shell, may actually be mirrors (following Taube 1992b. 1999).5

The headdress feathers and pendant tassels are damaged and barely

Houston, personal communication 2000), the meaning is unclear.

discernible.

However, it may be possible that this sign is derived from the verb

root pul, which can be glossed as "fire, or to be fired," especially The lord wears an elaborate hip- and loincloth, which is also

because the next glyph is composed of K'AK' 'fire' and possibly eroded. He may be seated on a pillow, and he gestures with his

ta 'torch.' The Diccionario Ch'ol (Aulie and Aulie 1978) gives right hand (which is now missing). Unlike the characteristic Clas

pul 'to burn' and mach mi lac pul jini cholel 'it doesn't work to sic Maya profile with receding forehead and chin, prominent nose,

burn the field.' Sometimes burning in Maya texts refers to censing and elliptical eye, the Tula plaque figure's facial features are an

something, warfare, conquest, and the destruction of a town's tem

gular, his bangs are straight cut, and a tubular nose ornament

ples; it may also refer to fires lit in agricultural fields and rituals passes through his septum. As a symbol of his royal status, he may

(research by David Stuart and Nikolai Grube, as cited in Scheie display a jester god or god K (k'awil) on his headband.

and Mathews 1998:148-149, 272, 379-380). Interestingly, the hi Many of these features also appear on Terminal Classic carved

and painted images in the Maya area (Scheie and Freidel 1990:385

eroglyph for fire on the Tula shell is similar to examples com

monly found in the Late/Terminal Classic inscriptions at Chichen 386, Figure 10.4b [Machaquilá Stela 5]; 391, Figure 10.8a [Jimba

Itza, where smoke scrolls (K'AK' 'fire') are suffixed with the Stela 1]). A similar profile appears on Seibal stela 10 (Graham

phonetic complement k'a (see Krochock 1988). The final hiero 1996: Figure 7:32 [Figure 12b]). These images are comparable to

those found on bas-relief columns at Chichen Itza (Morris et al.

glyph may be a version of the K'INICH 'sun-eyed/faced one'

1931; Tozzer 1957:153, 166. 172 ["an anomalous Toltec" (Fig

title, or it may represent the syllables ma sha ? ta ho(?).

In addition, there appears to be a formerly unreported bejew

ure 512) and an "anomalous Maya" (Figure 652)]) (Figure 12c);

on other stelae at Seibal (Graham 1996); and at other related Late/

eled hand touching the final hieroglyph on the reverse side. Prior

to breakage and re-carving, there probably was a scene carved

Terminal Classic eclectic sites. The profile and nose bar of the

above the glyphs that more than likely describe this lost tableaux.

Halal (Campeche) doorjamb figure is particularly close, and he

wears a headband and a stylized long-snouted reptilian headdress

It may have been another seated noble or a fire-starting scene

(Pollock 1980:Figure 925) (Figure 12a).

(possibly with a fire drill like that on a looted panel from the

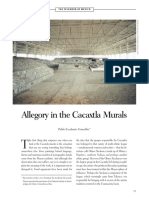

Close resemblances can also be noted between the Tula plaque

Usumacinta region [Stuart and Houston 1994:76]). It is also pos

and items of adornment worn by the battle-scene figures in the

sible that the now eroded image may have been a smoking lord

like the one on the incised shell illustrated by Scheie and Miller

Cacaxtla murals (Foncerrada de Molina 1982; Diehl and Berlo

(1986:155, Plate 59). 1989: Volume Figures 1-2). Many of the "feathered warriors" and

the central image on the east talud wear tubular nose plugs similar

On the front of the plaque, there are hieroglyphics above the

to the one worn by the Tula plaque lord (cf. McVicker 1985:90

figure's headdress, but they are now broken off or eroded and

difficult to discern. Phonetic hu (?) and chi signs can be picked 92, Figures 7-9). The mirrorlike pendants worn by figures 15, 24.

and 47 are also comparable to that on the Tula plaque. These

out. It appears to be the second part of T1:181:671 /u huuch or

yuuch, meaning "his/her shell," which is so common on Maya

shell artifacts. These signs are analogous to the glyph on the in 5 The Dumbarton Oaks plaque (Figure 9c) is badly stained by what

cised shell shown by Hellmuth (1987:251) and the halved carved has been identified as "iron rust," attributed to burial with an iron pyrite

conch shell illustrated by Dorie Reents-Budet (1994:43, Fig mirror. Although pyrite decays and leaves residues of various colors, fur

ure 2.8), which she reads as hach. However, the ha sign often ther testing is needed to determine the exact source of the "iron rust" and

distinguish it from burning. At Nebaj, pyrite mirrors were frequently en

works as hu when it is a prefix, as in huul, or the arrival glyph. It countered in Classic high-status burials, but they do not appear to be

is likely that the owner's name or title appeared at the end of the associated with caches containing jade picture plaques (Smith and Kidder

text, which is now broken off. The front text may have had the 1951:46,50).

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 183

5 cm

Figure 6. Photos of the Tula Plaque [by J. W. Palka

likeness all reaffirm theings and photographs of thisof

placement smallerthe

plaque and its present

Tula loca

plaque

minal Classic period, whention remain

styles unknown.6

shifted through encou

populations expanding In general,

into both the Tula the

plaque resembles the well-known carved

highlands and t

from the Mexican Gulf coast. jade plaque from Nebaj (Smith and Kidder 1951:Figure 59b),

The noble images most closely related to the Tula Plaque figurewhich is usually considered the type specimen (Figure 8a). Spe

cific similarities can be found in the carving of the left arm and

were carved on jade "picture plaques" (Proskouriakoff 1974:175—

hand and general similarities in the headdress and ear plug. Nine

192). To investigate the role played by the shell plaque in the

or more of these "Nebaj-type profile picture plaques" were re

dynamics of Classic Maya society, it will be assumed that the

carved shell from Tula, unlike other carved and incised shells, is covered from the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza7 (Proskouria

koff 1974:178-185, Plates 72-75). They were all broken, some

analogous to these objects, and perhaps served similar functions.

This analogy is supported by the size and portability of these

objects, their chronological placement from the Late to Terminal

Classic period, the posture and gesture of the seated figure and its 6 Morley (1938) gives a brief history of the Gann plaque and affirms

adornments, and the restricted range of headdresses, nearly all

that it was found by a workman near San Juan Teotihuacan at "the time of

falling into the general category of long-snouted reptilians. Leopoldo Batres." He relates that Batres gave it to Finance Minister Liman

tour, who took it to Paris. Later, Limantour's heirs sold it to Weston, a

Discussing jade plaques comparable in style to the Tula shell,

curio dealer in Mexico City, who then sold it to Gann in 1923 for $250.

Tozzer (1957:183) speculates that "[t] he wide distribution of these

For the story of how Gann took the plaque from Mexico, and the sub

jades seem to point to their center at Ocosingo [Tonina], Chiapas,

sequent scandal, see Givens (1992:142-143).

and possibly at Palenque and neighboring sites on the Usumacinta 7 In his letters from the field (to his mother), A. M. Tozzer (Peabody

extending to Piedras Negras." Unfortunately, with the exception Museum, Harvard University Archives, letter 20, April 20, 1905) de

scribes the wealth being taken from the Sacred Centote and the secrecy

of Tonina, not a single jade or shell plaque bearing the lordly

surrounding the finds. After recounting the magnitude of gold recovered,

image is documented from the entire Classic Maya southern low he goes on to state, 'And as for the jade, there is no end to it. There is

land heartland. However, Gann (1936:38) claims that the famous probably more of this precious stone taken from the Cenote than all. the

plaque from Teotihuacan that bears his name (Figure 8c), was museums in the country have in their united collections. The carving beg

"almost certainly manufactured in the great Maya art centre gars

of description and there are hundreds of pieces." He also says that the

utmost secrecy is being maintained for fear that the Mexican Government

Palenque, as in that city was found a smaller plaque upon which

may try to regain it. Finally, in the last decades, many pieces have been

was sculpted an almost identical design; moreover, the two were

returned to Mexico to form a collection comparable to that maintained by

Harvard's Peabody Museum (Table 1 Jades 3, 5).

probably made from the same slab of jade." Unfortunately, draw

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

184 McVicker and Palka

Figure 7. Drawings of the Tula Plaque

image and inscription [by J. W. Palka).

[a] Tula plaque image; [b] Tula plaque

inscription.

0 15 cm

shattered, and their surfaces suggest that they were burned as deposition in the cenote" (Moholy-Nagy and Ladd 1992:142). In

part of a ritual.8 fact, Tozzer (Peabody Museum, Harvard University Archives,

All the Cenote jade profile picture plaques have Classic Maya Tozzer to Putnam, December 3, 1904) finds it strange that "the

profiles and eyes and wear a variation of the same reptilian head shell ornaments and in fact every [sic] thing made of shell seems

dress. Proskouriakoff suspects that the one exception represents a to show the effects of their long burial beneath the water full as

"prototype" of the later carvings (Proskouriakoff 1974:184-85, much as those made of other materials." It is not surprising, if

Plate 75a [Figure 9b; Table l:Jade 9]). Stylistically Coggins (Cog shell plaques were present and they were destined for a sacrificial

gins and Shane 1984:27-28) places the others in the first part of pyre, that none of them survived.

the Early Phase which is dated 800-900 B.C. She speculates that

"[t] he jades, which represented the personal wealth of Maya rul

ers to the southwest, may have been tribute sent or taken to the COMPARISON AND DISTRIBUTION

new, foreign-dominated capital." The question of the concentra

tion of jade plaques at Chichen Itza and their distribution through In addition to the nine jade plaques from the Sacred Cenote, 11

out Mesoamerica will be taken up later. jade plaques have been identified for comparison that closely re

The one jade picture plaque excavated at Chichen Itza, a front semble the shell plaque from Tula (Figures 8a-d; 9a-d; Table 1).

facing seated lord, had been placed with other highly valued ob There are certainly a number of others (Rands 1965).9 One com

jects and jade plaques in a stone box cached in front of an earlier parable plaque is from Uxmal (Ruz 1955:62-63, Lámina XXV),

staircase inside the Castillo (Erosa Peniche 1939:241). It resem and the others with known locations range from Central Mexico

bles numerous frontal plaques recovered from the Cenote (Prosk (Digby 1972:30, frontispiece), through Oaxaca (Caso 1965), to

ouriakoff 1974:164-171, Plates 67-70) (Table 1:Jades 10-11; the uplands of Chiapas (Easby 1964) and Guatemala (Smith and

Figure 13c). However, Coggins (personal communication 2000) Kidder 1951). The aberrant Berlin plaque (Schmidt etal. 1998:588,

Number

feels that these frontal images wear ill-defined headdresses, some 279) is recorded as coming from Colipa near Misantla in

of which may be birds rather than reptiles, and are not strictly

comparable to the reptilian headdress worn on the Tula plaque.

It should be noted that no carved shell plaques were recovered

9 For example, in the Guennol collection volumes, two jade plaques

from the Sacred Cenote. Many of the other shell artifacts thatare illustrated (Rubin 1975:332, 1982:133). The former is on loan to the

were recovered were "intentionally broken, burned or both, before

Brooklyn Museum, and the latter to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in

New York. They fall solidly within the range of standard posture.-seated

lords. They are both small (7.2 cm and 9.75 cm, respectively), and one

faces left and the other right. The Metropolitan example has a clear long

8 Many Maya jade and shell artifacts were often burned as offerings

(Escobedo et al. 1990; Fash 1988:158; Freidel et al. 1993:242). When jade

snouted reptilian headdress; the Brooklyn Museum plaque's headdress is

problematic. Provenience is unknown, although it is possible that A. B.

reaches a certain temperature, it "explodes" and produces jade "popcorn."

This shattering is particularly intense when hot jade is thrown Martin

into cold

purchased at least the Brooklyn plaque from the "Michoacan cache"

water. referred to in note 10.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 185

Figure 8. Examples of Maya jade picture plaques: standa

and Kidder 1951:Figure 59b; courtesy Michael Coe]; (b] C

right President and Fellows of Harvard College); (c) Teo

British Museum); (d) Unknown (Table l:Jade 18), Univ

Pennsylvania Museum).

central Veracruz, and As noted plaque

the Princeton earlier, despite a c

(Reents-Bude

17) is said to come from Classic "Michoacan."10lowland Maya art, n

been recovered from Piedras

1951:47; Stephen Houston, p

lenque

10 The provenience of the Princeton plaque (Table l:Jade 20) is an (Ruz 1973) or other U

example of the difficulties encountered in researching they

plaque provefound at Seibal or Río

nience. Mathew Robb, assistant curator of pre-Columbian highland

art at Princ Guatemalan jades e

eton's Art Museum has provided the following information. "The Merrin

the Nebaj plaques, not a sin

Gallery purchased a group of jades in 1968 or 1969, said to be from

Classic

Michoacan. There are indications that these jades were cached as heir southern lowland Ma

ten

looms. The lot included three plaques and some beads. Gillett based on style, as would

[Griffin]

recalls a conversation about the group around the timeican Indian

of the conch shell silhouette described earlier and the

'Before

Cortes' show, and [szc] included Ed Merrin, Ignacio Bernal, Gordon Ekholm,

"prototype" Cenote Jade 9, both attributed to Palenque (Figur

and Jose Luis Franco. Their theory was that the Maya jades had been

Obviously, the manner in which the plaques were recov

looted in antiquity and had made their way to Michoacan through ex

and

change and trade." It is unfortunate that today jades are still recorded

being looted can not provide an adequate sample. Neverthe

someand

and making their way into various collections through exchange common

trade. dimensions and iconographic attributes pr

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

186 McVicker and Palka

Figure 9. Examp

dimensions], [a)

73:2; copyright

Cenote [Table

(Table l:J

l:J

and Fellows of H

et al. l957:Plate

Collections, Was

(after Ruz L. l95

suggestive comparisons.

in thickness. Th

to 14.1 cm in height

depth and

(Table f

1

Because they Nearly

are all

irregular pl

i

a rough surface

flares area

andwasusu

They fall on

into the

three pictur

catego

are mediumseats

(80-100

may cm2)

be f

Cenote jades variation

are in p

distribute

plaque, at 55.1 restingcm2, falls

acrossin

There is less is variation

paid to in

the de

(0.3-0.7 cm) incisions.

Cenote Jade 9 (

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

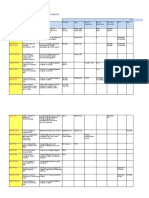

Source

(Figure 8a) (Figure 9a) (Figure 9b) (Figure 13c) (Figure 8c) (Figure 9c) (Figure 9d) (Figure 8d)

Star (189 :109) SmithandKid er(1951.-Figure59b) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate72:1,c/6 9) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate72: ,c/6 1) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate73:1,c/6 8) (Figure 8b) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate73:2,colrPatel, c/670) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate73:4,c/6 3) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate73:5,c/6 73) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate74:1,c/6 72) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate75:a,c/6 7) Proskuriakof (1974:Plate67:b2,C/6I03A) Morley (I946:Plate 93:c) Schei andMiler(1986:PIate34) Schei andMiler(1986:Plate6) Lothropetal.,(1957:PlateLXVI ) Easby (1964:Figure 2c) Ruz L. (195 :Lamina X V) Schmidte al.(19 8:Number279) Mason (1927:59, Figure 5) Joyce (l938:Plate Lie) Re nts-Budet(19 4:32 ;Number17)

Adornments0

nose barc col ar (heads) pendant beads face pendant bar beads bar pendant beads collar wrist mask, bar bar bar bar bar collar

A/C pendant. A/C, A/C, A/C, A/C, bar A/C, A/C, A/C, A/C, A/C, Sandals/C ?/C. A/C, A/C A/C, A/C, A/C, A/C c, ?/C, A/C,

Headdres LSR LSR LSR LSR LSR LSR LSR? LSR? LSR not LSR LSR LSR? LSR LSR LSR not LSR ?? not LSR LSR LSR? LSR

Profileb

non-Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya eye Maya eye Maya Maya Maya Maya Maya non-Maya Maya Maya Maya

Posture/Gesture8 Gesture left Standard left Standard left Standard left Standard left Gesture right Standard left Standard right Standard left Gesture left Full face Full face Standard left Standard right Gesture right Standard left Gesture left Standard right Standard right Gesture left Standard left

Sit ing Position unknown

on cushion? on thre heads on two heads on two heads on picture frame on picture frame on picture frame on picture frame on picture frame on solar cartouche standing seated on carved bench on throne or pil ow in niche on monster head on picture frame on picture frame on picture frame? broken, on picture frame?

Location

The Field Museum Museo Nacional Peabody Museum Museo Regional Peabody Museum Museo Regional Peabody Museum Peabody Museum Peabody Museum Peabody Museum Peabody Museum Museo Regional British Museum Museum American Indian Dumbarton Oaks of Natural History Museo Regional Museum fur Volkerkunde University Museum British Museum Princeton Art Museum

Chicago, Guatemala, Cambridge, MA, Merida, Cambridge, MA, Merida, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, MA, Merida, London, Washington, DC, Washington, DC, NewYork,AmericanMuseum Merida, Berlin, Philadelphia, London, New Jersey,

Provenience

Tula planted field Nebaj excavated ca he Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote Chichen Itza Cenote ChichenItzaElCastiloca he Teotihuac n planted field "Oax ca"unk own"colected" Unknown Tonina burial cache UxmalGovernor'sPal ce ache "Central Veracruz" Unknown Unknown Michoacan?

Dimensions

9.5 X 5.8 cm 10.6 X 14.6 cm 17.8 x 10.6 cm 14.2 X 1 cm 1 .5 X 14 cm 7.5 X 9.5 cm 6.1 X 5.5 cm broken 9 X 10.2 cm 12.0 X 13.5 cm 7.5 X 1 .5 cm unknown 14 X 14 cm 8 X 6 cm 14.1 X 8.6 cm 1 .4 X 5.5 cm 7.5 X 13 cm 7.2 X 9.2 cm 6.7 X 5.8 cm 5.8 X 7.5 cm 8.2 X 6 cm

Jade I Jade 2 Jade 3 Jade 4 Jade 5 Jade 6 Jade 7 Jade 8 Jade 9 Jade 10 Jade 12 Jade 15

TableI.ComparisonfeatursoftheTulasheplaquewith20Mayjdepictureplaqus Plaque Tula Shell Nebaj Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Cenote Jade 11 Gann Jade 13 Jade 14 Squicr Jade 16 Jade 17 Jade 18 Jade 19 Jade 20 LSR,long-s utedrpilan(setxfordesciptonadiscu on);A/C,anklets dcufs. aProfilegstu romheviw'sprcte:andposuritngwhoeluckdnr;oeha knripadoemcrsht;wenadrlokigeft,harmcoset;whnadrlokig right,lefamcroshet;figursoenvthaperncoflaig.Whensturig,oeamsxtnde.Ja9holdsnvabject;Jd19saer"bd-likojects. bMayprofilesatur smothlinefrom sethairlnedaliptcey.Non-Mayprofilesaturnoblerwidgesanroudeys. cMostfigureswarnkletsandcufs;bead,pctoralbs,orpendatsrecom n.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

188 McVicker and Palka

Despite strong resemblan

ments, rarely these figures

figure, lack nose bars, and

eye. This may indicate tha

plaques were carved in a d

what earlier time than the

the Tula plaque was re-car

Except for their restricte

plaque figures are remark

on Classic Maya polychro

even bone. This also sugge

dates the Tula plaque imag

Cream polychrome vase ill

322) (Figure 10) is almost i

an exception, even sports a

"Princeton" plaque (Table

ble image. Other painted

figures are also illustrate

ures 4-5), Gallenkamp

Figure II. A Late Classic carved-stone image of a seated lord. Bonampak an

(1989:460, File

Sculptured Panel No. I No. 4113)).

[Scheie and Miller 1986:116, Figure 11.8; drawing by

chaeological Lindacontext Scheie]. and ca

Several of the stone carv

palace scene with a seated

Tablet and the Palace Tablet (Scheie and Miller 1986:114-115,

Figures 11.5, 11.7). Bonampak Sculptural Panel 1 (Scheie and 1990:302, Figure 7:19c). As is generally the case with the poly

Miller 1986:116, Figure 11.8) (Figure 11) repeats the scene, as chrome vessels, none of these seated monumental bas-relief fig

does a relief carved on La Pasadita Lintel 3 (Scheie and Freidel ures wears a headdress that falls within the range of those commonly

worn by jade plaque figures.

A related set of carvings of seated lords from the northern Yu

catan peninsula, although reminiscent of southern lowland panels

and pots, are later than the Late Classic-style jades and in style

closer to the Tula plaque. Examples are the seated "elite male" on

the tablet thought to be from Oxkintoc (Gallenkamp and Johnson

1985:139, Figure 68) and the seated lordly figure on the carved

Ak'ab Tz'ib lintel from Chichen Itza (Maudslay 1889-1902:Vol

ume III, Plate 19).

Images from Xochicalco—most notably, the sculptures sur

rounding the base of the Temple of the Plumed Serpents (Hirth

2000:33, Photo 3.1; 36-37, Figures 3.5-3.6) (Figure 4b)—share a

number of features with the Tula plaque. These seated bas-relief

figures enclosed by serpent coils wear beaded necklaces (without

pendants) and both wrist and ankle bracelets; their right arms are

across their chests; and they wear saurian headdresses lacking

lower jaws.

Another example is the tablet labeled by Covarrubias (1957: Plate

LVI) "in the style of Xochicalco" (Figure 4a). This relief carving

was excavated by Batres (1902) in his explorations in the Calle

Escalarillas in Mexico City. Unless it was looted by the Mexica

from Xochicalco, it is a prime example of Aztec archaizing

(cf. Pasztory 1983:141).

Although there is little variation in posture, gesture, and cos

tume of Maya seated lords regardless of media, the headdresses

worn are an exception: Rarely do plaque figures wear anything

other than a variation of a long-snouted zoomorphic headdress

(Table 1). Scheie and Miller (1986:78) note that the reptilian fig

ure in the headdress worn by the figure on the Tula Plaque is

marked by feathered fans on its forehead and muzzle and identify

it as a vision serpent. Taube (1992a) argues that these headdresses

are derived from the Teotihuacan war serpent (in Maya texts: wax

Figure 10. Late Classic Zacatal Cream Polychrome vessel image of a seated aklahun ubah chan) and are ancestral to the Aztec fire serpent.

lord [Reents-Budet 1994:9; courtesy Justin Kerr). Andrea Stone (1989) also discusses the elite use of this Teotihua

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 189

:Cvl

Figure

Rgure 12. 12.

MayaMaya

Terminal

Terminal

Classic column,

Classic

stela, and

column,

doorjamb stela,

images, (a)

and doorjamb ima

Halal

Halal Acropolis,

Acropolis,

sculpturedsculptured

doorjamb figure

doorjamb

[after Pollock

figure

1980:Fig[after Pollock 19

ure

ure925); (b) Seibal,

925); detail, Stela

(b) Seibal, 10 (after

detail, Graham

Stela 10 l996:Figure 7:32); (c) 1996:Figure 7:3

(after Graham

Chichen

Chichen Itza, Itza,

TempleTemple

of the Warriors,

of the column

Warriors,

I0W (Morriscolumn

et al. l931:Plate

I0W (Morris et al. l93

50).

&

i i§gn

III UBlTtSrr

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

190 McVicker and Palka

can headdress shell was too fragileas a

to attempt perforations"forei

for either purpose and

particular was intended to be held"frontal

the in the hand. m

three stelae Thereat Piedras

is little agreement N

about the identification of the plaque

Regardlessfigures. of They are usually

their referred to as lords, although

spec whether

cation as vision serpent,

they are portraits of individuals or stylized types remains undeter

blance betweenmined. Coggins (personal the communication 2000)May suggests that if

those of thethe plaque images were self-portraits, they would not be worn.

processional

itla at Teotihuacan (Mil

This would help explain why figures in Late Classic-period mon

ure 14) is umental and minor arts never wear or display them.

significant becaIndividuals

foreigners, appearing

enemies, on plaques have also been consideredor cult representa

an

In the remarkable

tions of warriors, priests, and gods.12 series

Jaina illustrated Additional comments on the bycondition of the jade plaques may

Schei

ing serpentclarify the current state of the Tula

heads shell. Plaques are frequently

withou

(Scheie referred to as broken and/or re-carved. This assessment is

1997:91-92, based

Figu

the sectionon the observation that many of the headdresses

titled "Warri are incomplete

numerous and often appear sliced in half by a picture frame;

examples of the framesth

ures (Scheiethemselves1997:95-119)

sometime appear to have been re-carved. One Cenote

convention jadeis (Proskouriakoff

to 1974:172,

havePlate 71 :c3) is neatly the

sawed in

both feet half just below

on the the figure's waist. Other images seem to be inter

ground

typical rupted by the irregular shapelord"

"leaning of the stone. Some reshapingpo of

Practically plaques

all could have plaques

been deliberate, pieces being removed for other

hav

Some are ritual purposes—much like potlatch

drilled coppers on the Northwest

through

These Pacific coast being

various drill"broken" during ceremonial

marks feasts. It appears

suspension, thatleading

the missing arm on the Tula plaque wasto the result of purpose

the

as pectorals,ful mutilation rather than natural breakage.13

pendants, go

for this assumption. Alth

presented on ceramics and

this figureCONCLUSIONS

wearing one

In fact, the larger plaqu

comfortable to wear around the neck. Distribution

It is likely that many of the holes were not for suspension but

for the attachment of additional adornments or the inlaying of Jade and shell figural plaques have been described as objects of

semiprecious stones. This appears to be the case in other types trade,

of pilgrimage offerings, and tribute. Their most remarkable

distributional characteristic is their absence from Classic Maya

pendants worn by lords on painted pottery and stone reliefs (cf. Ma

son 1927:64; Proskouriakoff 1974:175). These perforations may

also have been used to attach the plaque to a cloth or other

12 Ringle et al. (1998:207) classify the figural jades as Quetzalcoatl

material. The Squier plaque from Tonina (Easby 1964:Figure cult

2c objects. Their proposed association of plaques with Quetzalcoatl is

[Table l:Jade 15]) is a case in point. Although it is drilled through

rather tenuous, based largely on the relationship at Xochicalco between

horizontally above the shoulders and could easily have been susthe feathered serpent and the lords enfolded in his coils. Because the

Xochicalco carvings are later than most of the jades, and because these

pended, eleven additional holes were drilled at right angles from

Xochicalco figures were probably modeled on the earlier jades, it seems

the edges to the back, an ideal arrangement for sewing the jademore likely that the Terminal Classic Quetzalcoatl association was a later

to a backing. Coggins (Coggins and Shane 1984:142) suggestaddition to the leaning-lord iconography. Miller and Samayoa (1998) have

that it is possible that they were hung within palaces as emblems

recently proposed that at least some of the earlier Chichen Itza jades were

connected with the worship of the maize god.

of rulership and wealth. Again, not a single depiction of a plaque

13 The deliberate mutilation of jade objects is well documented for the

being displayed is known, even in palace scenes.

Olmec. For example, in the Guennol Collection ( Rubin 1975:311) an Olmec

Remarking on a spondylus shell disc carved with a kneeling jade plaque is described as having been "killed" by carefully sawing off an

figure. Smith and Kidder (1951:54, Figure 88b) state, "The fact arm. It is possible that the missing arm on the Tula plaque was deliberately

removed rather than broken.

that none of the three perforations is so placed as to allow the

Other factors that may explain the condition of the plaques under

object to hang right side up, as a pendant, suggests that it was

consideration are the hardness and preciousness of jade. It is possible that

designed for attachment to clothing." The Tula plaque is puzzling

the irregularity of the green stone may have guided the completeness of

because, despite the numerous surviving drill marks, none appears

the image. Jade is a remarkably hard mineral, and in many cases it may

have been more practical to follow the irregularities and save the effort of

suitable for attaching to a backing or for suspension. Perhaps the

completing the recognizable iconography. Rubin (1975:309) suggests that

"the original [Maya] artisans often modified the original shape of the

stone [jade] as little as possible, taking advantage of the natural forms to

" Although a full discussion of frontal figurines on jade express their purpose." Jade is a remarkable precious commodity, and in

plaques

is beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth noting that Proskouria many cases irregularities may have been preferable to losing any of the

koff (1974:160-161, Plates 67b-70) illustrates a series of Late material. Easby (1968:15) remarks on how the surface imperfection of

Classic Maya "stela" plaques from the Sacred Cenote, which are "dressed Maya jades, and "attempts of the lapidary to adapt the form to the original

in the full regalia of a warrior figure that one might encounter at Piedras shape." offer evidence for the scarcity and high value placed on the raw

Negras, with the lower jaw of a monster headdress hanging on the chest, material. How the fragility of shell, its relative availability, and bivalve

and the upper jaw sharply upturned with a double scroll above"form may have affected the carving of images on the Tula plaque is diffi

(Figure 13b). cult to assess.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 191

Figure 13. Full frontal figure

rior" headdresses,

headdresses, (a)

(a) Pied

Pie

Stela 26 (drawing

[drawing by John

ery); (b)

ery); (b) Jade

)ade picture

picture plaq

pla

of Sacrifice, Chichen Itza

koff 1974:164, Plate 67:b2

(c) Jaina figurine [after

(after Sch

Figure 34; drawing by J. W

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

192 McVicker and Palka

Figure 1

from Teo

sional Fi

FigureVI.

ma).

sites in the central Peten and in the Usumacinta region (cf. Coe cached jades are all in nearly perfect condition and show no signs

1959). As portable objects, they are known to have been recov of burning. The fragile Tula plaque, with the exception of the

ered from the central Mexican highlands (Tula, Teotihuacan), "Mi broken or deliberately removed left side, was also in excellent

choacan," Gulf Coast, southern highlands (Monte Alban), the condition. Apparently, two or more distinctive rituals of disposal

northern Maya lowlands (Chichen Itza, Uxmal), and highland Maya were involved, reflecting chronological and cultural differences.

areas from Chiapas (Tonina) to Guatemala (Nebaj). Where they It is significant that not a single comparable picture plaque,

were manufactured and how they were obtained before they were regardless of time or region, is known from a tomb and associated

distributed are basic questions. Currently, there is no evidence to with a particular individual. Even the Tonina jades appear to be

support Tozzer's (1957:183) speculation that they were produced associated with secondary burials in cremation urns and had been

in the central Usumacinta region or at Tonina. If they were man placed in a separate jar (Easby 1964:60). Because the shift to

ufactured in the style of Palenque and Piedras Negras, why are cremation burials is a hallmark of the Early Postclassic period in

they absent from these excavated sites? the Maya highlands (Ruz 1968; Woodbury and Trik 1955), it would

Proskouriakoff (1974:14) has suggested that jade plaques were appear that these Classic jades, like the Tula plaque, also were

items looted from graves and caches following the collapse of the heirloomed and cached at a time that Central Mexican ideologies

southern lowland Maya cities in the ninth and tenth centuries. She had penetrated into Late Classic domains.14

bases her speculation in part on Aztec jade looters implied in Given the remarkable preservation of the Tula shell plaque, and

Chapter 8 of Sahagún's book 11 (1963:221). Yet, a sufficient num the lack of known elite burials at Tula, it seems likely that what

ber of richly stocked, unlooted Late Classic Maya tombs have was found in the cultivated field was a cache containing the pre

been excavated, and none has yielded a seated-lord picture plaque. cious shell and other "treasures." It is unfortunate that we do not

If, with the disruption of trade routes in the ninth century, jade have more precise information on its provenience. Another remark

became such a rare commodity, it is more likely that some plaque able ofrenda from Tula also contained mother-of-pearl, in this

carvers may have turned their attention to shell as a precious raw case the famous shell mosaic anthropomorphic censer lid in Toltec

material. style excavated at El Corral (Acosta 1974).

How, why, and where plaques were deposited is unclear. Un Most authors assume that the plaques were direct trade or trib

fortunately, most are looted and unprovenienced. The few from

ute items but do not address the exchange system that might have

excavated contexts are all from caches, and were frequently placed

in jars or stone boxes (Chichen Itza [el Castillo], Nebaj, Monte

Alban [votive deposits in the Temple of the Jaguar. Rands 14 The Tonina jades, discovered (but not excavated) by Squier in 1852

(Squier 1870), form the largest collection of jades recovered in situ. The

1965:906], Tonina). Ruz (1955:62) interprets the deposit in which

three largest are a profile lord, a stela style, and a face plaque. Several

the Uxmal plaque was discovered as the scattered remains of smaller

a pieces were in the cache, including what appears to be a fragment

cache that had once been placed in the small platform supporting of a second leaning lord. The large, seated profile figure (Table l:Jade 15)

the double jaguar-headed throne in front of the Governor's Place.is unusual in that he wears an elaborate headdress without the features of

The most striking difference between cached jades and thosethe long-snouted reptilian and is seated on a cauac earth-monster head. As

discussed in the text, this jade had been perforated on all side's to be

from the Cenote of Sacrifice is the condition of the plaques them

attached to a backing. Unfortunately, several of the smaller jades from the

selves. As discussed earlier, all comparable Cenote jade plaques

cache have disappeared. The remainder are in the collection of the Amer

show evidence of burning and are in a fragmentary condition. The

ican Museum of Natural History.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya carved shell plaque from Tula 193

been The Tula figure, like itsLothrop

in operation. For example, jade counterparts, is portrayed

writes, in the "T

jades passed in trade or formal

as posture

tribute of Maya rulersovergiving an audience

great (Scheie distan

and

positive evidence that some

Miller 1986:78).were inherited

If a high-ranking for

foreign dignitary was granted ma

before they were buriedan audience orwith

received a royal their

visit, what better owners"

gift than a pre (

1957:253). Referring to a or

cious jade "Nebaj-style"

shell representing kingly authority and plaque

possessing fr

shared symbolic

Cenote, Coggins comments that value? "the plaque may h

or carried as spoils or as an

The giving offering

and accepting to

of highly valued gifts has Chichen

long been

southwestern Maya regions. However

recognized as the most fundamental symbol of it traveled,

alliance. Describ

probably tied the Oaxacan

ing Germanic center of

societies, Mauss (1990:60) Monte

summarizes the signifi Albá

cinta region of its origin"

cance of the gift (Coggins and

in essentially feudal and peasant Shane 1

societies:

et al. (1998:207) propose that pilgrims may have car

as tokens of religious veneration.

The clans within the tribes, the large undivided families within

Diehl (1983:114) explores the

the clans, the tribesanalogy with

one with another, the chiefs among them Aztec

traders (pochteca) to explain extraregional

selves, and even the kings among themselves—all lived to a item

fairly large extent morally

Tula. Unfortunately, pottery and and economically

a few outside themiscellan

closed

confines of the family

marily Papagayo Polychrome group. Thus,Plumbate

and it was by the form of the from

gift and alliance, by pledges and in

ica, were all that he encountered hostages, his

by feasts and presents

excavation

that were as generous as possible, that they communicated,

of Huastec trade pottery from the northern Gulf

helped, and allied themselves to one another.

toys (presumably from the Huasteca), and some j

rine shell from the Pacific were also collected. Notable in their

absence were other exotic goods from the central and southern Although marriage and lineage alliances were often sealed with

Gulf Coast (e.g.. Fine Orange) or any artifacts from the feasts

Maya and gifts, the underlying function of the giving and exchang

marches or heartland. Although he had hoped to "uncover ingevi

of elite objects was often political and economic. The classic

dence of Huastec or other foreign residents in [his] Corral Localwould be Malinowski's analysis of the Kula Ring (1978

case

[1922]).15 As Malinowski points out, the seemingly "irrational"

ity excavations, nothing [he] found indicates the ethnic affiliation

of the occupants" (Diehl 1983:143). It remains one of the exchange

Meso of shell armbands for necklaces was a chiefly activity

american archaeological puzzles that architectural ideas and that set the scene for active trade on the beach. Even today among

sculp

many peoples of Mesoamerica the establishment of ritual com

tural forms could have passed so freely between Tula and Chichen

padrazgo kinlike relations accompanied by gift-giving is thought

Itza, and that, with the exception of the Tula plaque, all portable

objects were filtered out (cf. Wren and Schmidt 1991). to be essential to the establishment of alliances and trading part

nerships (Nutini 1984:23-28, "the mediating entity"; cf. Vogt

Of course, the presence of a single portable object at Tula,

which may have originated in the northern Maya lowlands, 1969:236-238).

need Even though the present form of these exchanges

say nothing about any direct connection between the Toltecs is post-Conquest, their functions are ancient.

and

the Maya. However, the fact that the object was carved or Gift-giving

re among and to members of the elite was common in

Mesoamerica. Kepecs et al. (1994:141) discuss the significance of

carved in "Mexicanized Maya" style and considered of sufficient

this pattern of gift giving and the "power that preciosities confer

value to be cached at the Toltec capital does suggest a conceptual

connection between the two peoples. on elites who control them." They note that "the calculated distri

bution of these goods to secondary elites and middle-level groups

It is obvious that the initial carving of the plaques considered

establishes nets of obligations that contribute in many ways to the

here predated the establishment of Tula as a metropolitan power.

mobilization

In the Late Classic period, it is likely that the plaques were pre of energy."

Landa (Tozzer 1941:95-97) describes gift-giving among Yuca

sented to high-status visitors or travelers to Maya domains and

became symbols of alliance. It is even possible that the tan Maya nobles at the time of the Conquest. Sahagún (1959,

Maya

Book 9:8, 47, 55) records the tradition of gift-giving among the

lords carried carved plaques with them on their royal visits (Scheie

elite

and Mathews 1998). As high-status items, they would have bepochteca. Brumfiel (1987) reviews the evidence for both

come heirlooms and been handed down through the generations. tribute and special-occasion gifts being received by Aztec elites

Later, they might have reached their final destination through from

a foreign nobles and rulers. When these foreign nobles at

tended the great dedication ceremonies at Tenochtitlan, they in

new network of indirect exchange, redistribution, or tribute among

Terminal Classic eclectic centers such as Xochicalco, Cacaxtla, turn were presented with high-status items as gifts (Lambertino

and El Tajin, and ultimately Tula and Chichen Itza. Urquizo et al. 1999). In his analysis of the role of interelite soli

darity in achieving the aims of empire, Smith (1986:75) emphasizes

the role of sumptuous feasting, gift-giving, and royal redistribu

Functions tion in promoting social solidarity. The dispersal of high-value

items through the political economy of gift-giving may better ex

If picture plaques produced as Late Classic presentation objects plain the distribution of plaques than trade, tribute, or Postclassic

were carried to foreign realms as objects of veneration or insignia looting (cf. Dietler 1999 ["commensal feasts" and "diacritical

of political alliance rather than as personal possessions, they would insignia"]).

not be entombed but would eventually be cached at the appropri

ate ritual moment. If carved picture plaques were intended to be

15 Mauss uses Malinowski's description of the Kula Ring and Franz

given to establish external and peripheral alliances, then their ab Boas's description of the Kwakiutl potlatch as his basic examples of the

sence from the southern Maya heartland would be explained. socioeconomic importance of the gift.

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.114 on Sat, 23 Apr 2022 17:34:09 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

194 McVicker and Palka

Luxury itemsthe history of from

contact with Teotihuacan, andforeig

the presence of the

ural aura. AsGann plaque Kepecs

at that great metropolis, they may et al.

have reached as far

geographic as Central Mexico. By Terminal Classic times,

distance as "merchant war

often

The ability riors, called the

of the Putún, meddled ruler

in the affairs of Maya kingdoms

to

critical to and eventually established new hybrid dynasties that prospered

maintaining his at

laden exotics"the expense as of the traditional

gifts,Maya governments" (Scheiecor and

similar to Freidel 1990:380;compadre

the cf. Thompson 1970:3-5), the southern cities n

change of were eclipsed, and heirloomed plaques moved

"cultural on to the growing

diacrit

alliances maritime centers oflong

over the southern Gulf coast. From distan

these distribu

tures (Kepecs

tion points theyet were dispersed al. 1994:

as trade networks and elite inter

Hirth (2000:264-266)

action expanded north to El Taj in and up into the central rein

Mexican

of cultural highlands.

diversity, The desire for prestige goods symbolizing fore

contact with

Xochicalco. the

Hedistant Maya increased

claims among the Epiclassic "Mayanized

tha Mex

political alliances import

ican" populations of Xochicalco and Cacaxtla and, ultimately, Tula.

dence At this time of dynamic

that these eclecticism the flow

and reversed, and the

comm

ing dynast now-Mexicanized

with Maya style spread

accesswidely up the Usumacintat

symbolic and into the northern Maya lowlands

systems. At(cf. ThompsonXoc 1970:43:

the Temple "Theof

. . . hybrid Maya-Nahuat").

the WhenPlume

Chichen Itza became the

elaborately carved

dominant Terminal Classic/Early Post Classicstelae

center, its lords con

striving to tributed to the "Mayanization of Mesoamerica"their

reinforce (Scheie and Fre

forms and idel 1990:396; cf. McVicker 1985).

symbols to show

foreign As plaques were passed downThis

societies. generation to generation, and as

inte

in rulers and realms ebbed and

monumental flowed, they would naturally be re

sculpture

ported portable

carved—whether to be appropriate objects

to a new lord or to retain ref

2000:200-201, Table

erences to a hallowed 9.9).

past. This would explain the unusual features

"Mayoid" of the Tula shell pendants

jade plaque, such as its disregarded inscriptions, "non d

pent headdresses"

Maya" features, nose bar. and straight-cut(Hirth

hair. The plaque's re

The carving probably reflects the shifting

iconography of fortunes of the Itza and the

these

headdressesnew of style of Tula and "Toltec Chichen." Like the carvings and

leaning-lor

members of muralsa at Xochicalco

foreign and Cacaxtla, the Tula carved shell may

elite

identified as a

signal further signifier

interaction between the poorly documented "Putún o

connected with

Maya" of Tabasco or later Teotihuac

Maya of Campeche and the Terminal

reptilian Classic/Early Postclassic cultures of central Mexico. migh

headdresses This is yet

ographic significance

another example of the power of Chichen Itza as a center of "May (St

(Miller anization" as its transactions stretched

1973:101, Figure along the Gulf Coast-Tula 1

are probably axis, leavingassociated

"preciosities" in its wake. w

display images With the ascendancy

of of Chichen Itza, a large number of plaques

war, dea

Figure 193).carved with the leaning-lord headdress

The image were concentrated at that site.

to those This is in marked contrast

worn by to their scarcity

the at other Mesoamerican

ma

ings now known to

sites. These objects may by this time have have

been incorporated into

1988b) rituals used to proclaim

(Figure 14).new forms of political

This alliance. Scheie c

which were andrecovered

Freidel (1990:393) propose that the confederate lordsan

of Chi a

headdress. chen Itza "[transformedMillón

Rene kingship into an abstraction, vested

intin

residence ofobjects, images, and places." These lords then "terminated

kinsmen with the

Ion office of king and the

1988:107). He principle of dynasty that had generated it"

suggest

paxco were (Scheie and Freidel 1990:375). To acknowledge this disjunction

residences wit

painted publicly, carved plaques

images as emblems of ancient kingship may have

represent t

critical role of external relations that characterized seventh been ritually killed and thrown into the Cenote of Sacrifice to

century Teotihuacan. signify the death of the older order.

Toward the end of the Late Classic period, when most of the Coggins and Ladd (1992:341) recognized that "most of the

objects found in the Cenote were deposited in destructive cyclic

jade plaques were carved, they signified external relations with

Maya centers on the periphery of the southern lowlands. Given completion or 'termination' ceremonies." Ball (1992:193) went

even further and suggested a single massive act of ritual destruc

tion that terminated Chichen Itza's religious and political domina

tion of the northern lowlands. If such acts took place, vassal lords

16 Helms (1993:4) elegantly sums up the significance of the circula

tion of prestige goods and their transformation: "By obtaining such goodsand allies throughout Chichen Itza's sphere of influence might

[valuable resources] from afar, persons of influence, or elites, are involved have brought jades and other objects to be added to the most

in symbolically charged acts of both acquisition and transformation bycolossal cache of all. However, rather than terminating Chichen