Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stopping Sperm at The Source

Uploaded by

MicheleFontanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stopping Sperm at The Source

Uploaded by

MicheleFontanaCopyright:

Available Formats

View all journals Search Login

Explore content About the journal Publish with us Subscribe Sign up for alerts RSS feed

nature outlook article

OUTLOOK 16 December 2020

Stopping sperm at the source

Download PDF

The development of male contraceptives has slowed in the past decade, but some

Related Articles

preliminary studies are showing promise.

Reproductive health

Michael Eisenstein

Strengthening society with

contraception

Religion is not a barrier to family

planning

Better birth control

Why is long-lasting birth control

struggling to catch on?

The drug that could save the lives of

many women

How much should having a baby cost?

Equal opportunities begin with

Scanning electron micrograph of sperm production showing the heads (green) and tails (blue). Credit: contraception

Susumu Nishinaga/SPL

Research round-up: reproductive

When the University of California, Davis, announced in June that it was recruiting health

heterosexual couples as part of an international clinical study to test a male contraceptive gel,

the researchers were quickly overwhelmed. “Phones were ringing off the hook with people

wanting to take part,” says Richard Anderson, a reproductive-health specialist at the

University of Edinburgh, UK, who is one of the study’s principal investigators. Subjects

Health care Public health Biotechnology

The need for effective male contraception is real. A global survey from the New York City-

Medical research

based Guttmacher Institute found1 that 48% of pregnancies from 2015 to 2019 were

unplanned, even though there is already a range of contraception options. Diana Blithe, chief

of the Contraceptive Development Program at the US National Institute of Child Health and

Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Maryland, thinks that many men would like to try

alternatives to condoms and vasectomy. “Surveys have found that about 60% of men say

they’re interested,” she says. Sign up to Nature Briefing

An essential round-up of science news,

The gel in the current trial, which combines the hormones testosterone and segesterone opinion and analysis, delivered to your inbox

every weekday.

acetate (marketed as Nestorone), is the first male contraceptive to enter efficacy testing in

more than five years — and offers a rare glimmer of hope after decades of setbacks. “One of

the cynical jokes in the field is that a male contraceptive has been 5 years away for the last 40 Email address

years,” says John Amory, an endocrinologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. And e.g. jo.smith@university.ac.uk

although several other promising options are now in development, they will have to clear a Yes! Sign me up to receive the daily Nature Briefing

high bar in terms of matching the efficacy of female contraception, while producing minimal email. I agree my information will be processed in

accordance with the Nature and Springer Nature

side effects, if they are to make a meaningful difference to family planning. Limited Privacy Policy.

Valuable lessons Sign up

Hormonal contraceptives that prevent ovulation have transformed women’s reproductive

health and freedom. In a similar way, much of the effort regarding male contraceptives is

targeted at blocking sperm production. In the 1980s and 1990s, the World Health

Organization (WHO) oversaw trials of testosterone as a contraceptive. Although known as a

driver of male sexual development, testosterone can suppress the release of the pituitary

hormones that stimulate the production of sperm. In 1996, WHO researchers reported that

98% of a cohort of 399 men injected with testosterone achieved a meaningful reduction in

sperm count2, and 70% had no detectable sperm at all. In this latter group, no pregnancies

were reported, and only four occurred among those with reduced sperm counts.

The study was intended only as a proof of concept because high

RELATED

doses of testosterone can produce unwanted side effects linked

to mood, weight gain and levels of cholesterol. Subsequent

studies have therefore paired testosterone with hormones

related to the female sex hormone progesterone. Such

‘progestogen’ compounds inhibit the release of the pituitary

hormones, but they also shut down the production of

testosterone — so extra testosterone must be added to maintain

a normal hormonal balance.

Researchers at the WHO tested3 this combination of hormones

Part of Nature Outlook:

in 320 men between 2008 and 2012. They combined

Reproductive health

testosterone undecanoate — a testosterone variant that lasts for

longer than normal in the bloodstream — with the progestogen

norethisterone enanthate. The study found that nearly 96% of men reached the target for

sperm-count reduction. “Those men and their partners had very few pregnancies — that was a

big deal,” says Christina Wang, an endocrinologist at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in

Torrance, California, who was a consultant for the WHO.

Unfortunately, the trial was terminated early because of concern over some adverse events,

mainly related to mood swings and injection-related pain. Wang laments the termination,

pointing out that the problems resulted mostly from inconsistent reporting of side effects at

different sites. “Over 90% of these complaints come from one site,” she says, adding that the

facility in question saw a change of leadership part way through. But the WHO was sufficiently

concerned to call a halt. “This was really very controversial,” recalls Wang. “They stopped the

study without consulting the main investigators, or the people managing it, or the

independent data and safety board.”

This trial and others did not result in any clinical approvals, but they did provide some

valuable lessons. For example, it became clear that completely stopping spermatogenesis is

not practical, so researchers need to identify a cut-off level that leads to effective sterility. In

fertile men, ejaculate typically contains more than 15 million sperm per millilitre, and early

trials suggested that reducing this to one million per millilitre would be sufficient. “The idea

was that one million and below would give you an overall contraceptive efficacy comparable

to the female pill,” explains Anderson. But researchers have found that some people take

much longer to reach this threshold than others. “Some men get there in two to four weeks,”

says Blithe. “Other men take 16 to 20.”

Building excitement

Research into the combination of testosterone undecanoate and norethisterone enanthate

was supported by Berlin-based pharmaceutical company Schering AG until it was acquired by

Bayer, based in Leverkusen, Germany, at which point the investment stopped. This left the

field with no clear success stories, no established regulatory pathway to market approval, and

the difficult task of developing a drug that is safe enough to be used by millions of healthy

men. Understandably, pharmaceutical companies have been reluctant to try. “There really

aren’t any major companies that I’m aware of with active R&D programmes in male

contraception,” says Amory.

This dismal history helps to explain the excitement about an ongoing phase II trial of a

combination of testosterone and Nestorone, which is being backed by the NICHD and the

non-profit Population Council in New York City. Neither compound can be taken orally, but

both are available as topical gels that can be absorbed through the skin. Anderson says that

Nestorone is a particularly potent progestogen and remains active in the circulation for twice

as long as testosterone, which must be replaced daily. “So there’s a built-in safety mechanism

if you miss a dose,” he adds.

An initial trial4 showed that 84% of men receiving this combination saw their sperm count fall

below the threshold of one million sperm per millilitre within 28 days, with no serious adverse

events. The gel might also prove more popular than the intramuscular injections used in

earlier trials, which were among reasons cited for men dropping out.

The current trial is expected to involve 400 heterosexual couples from the United States,

Europe, South America and Africa. Recruitment was paused by the COVID-19 pandemic but is

now half-completed, and the first data are rolling in. “Our first couples have actually finished

the trial, and we’ve got a lot who are just finishing their year of contraceptive use,” says

Anderson, adding that the efficacy data so far have been encouraging.

According to Amory, who works at the trial’s Seattle site, a small percentage of men are failing

to respond to treatment — a similar figure to that in previous hormone trials. These failures

are frustrating because there is no clear indicator of who will, or will not, benefit.

But when it works, users are enthusiastic. “I’ve been doing exit interviews with some of these

guys, and they love it,” Amory says. With 200 couples left to recruit, and the study lasting

roughly 18 months for each couple, proof of effectiveness will be a long time coming. But the

process could clarify how the US Food and Drug Administration and other regulators

approach approval decisions for male contraceptives.

Beyond hormones

Many researchers favour contraceptives that use hormones because the systems involved are

well defined. “We know them, and we know their side effects,” says Wang. But hormones are

not the only game in town.

Non-hormonal contraceptives that target the production, function or release of sperm offer a

more direct and fast-acting alternative to hormones but bring new risks. In the 1980s, the

plant-derived compound gossypol was found to prevent pregnancy in clinical trials in China.

Its sterilizing effects proved irreversible in roughly 20% of men, however, and a few

experienced episodes of muscular paralysis.

Despite the problems, some promising non-hormonal options are emerging. For example,

there is interest in targeting retinoic acid, a compound manufactured from vitamin A that

helps to drive spermatogenesis. “It’s been known for a very long time that if you put mice on a

vitamin A-deficient diet they become infertile,” says Gunda Georg, a medicinal chemist at the

University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, who has been developing inhibitors of retinoic acid

synthesis.

Amory points out that early attempts to suppress the synthesis of retinoic acid blocked an

enzyme responsible for alcohol metabolism, such that drinking led to severe sickness. His

team has since designed some drug candidates that could suppress the production of

retinoic acid without causing such off-target effects.

Several start-up companies are now investing in non-hormonal strategies. Georg has spoken

to several companies about her work on compounds that reduce sperm motility. “You could

envision it for male contraception, but also for female contraception — for example, you

could do a vaginal gel,” she says.

The Male Contraceptive Initiative, based in Durham, North

RELATED

Carolina, has also been funding research on non-hormonal

drugs. “We support basic science and discovery as well as

preclinical studies and established development programmes

that are working towards human trials,” says Logan Nickels, the

organization’s research director.

More from Nature Outlooks

The body is now backing several promising commercial

programmes. For example, Revolution Contraceptives, based in

San Francisco, California, and Contraline, based in Charlottesville, Virginia, have developed

products that physically block the flow of sperm through the vas deferens. In principle, this

obstruction can be reversed non-invasively. “They both have promising animal data,” says

Nickels, although he notes that data are still lacking in terms of demonstrating full

reversibility in live animals or humans. He is also enthusiastic about work from Eppin Pharma,

based in Durham, North Carolina, which has developed a pill that reversibly inhibits sperm

motility in a non-human primate model.

Any breakthrough could reawaken the interest of big pharma, and Nickels doesn’t see the

current race as a zero-sum game. Much as women opt for pills, diaphragms or intra-uterine

devices, “all of these things are going to be important to establish a mix of methods that fit a

lot of different men’s lifestyles”.

Progress in male contraceptives might seem slow, but Anderson thinks that many men and

women are keen to find a good alternative to condoms. “We’ve just had such a dearth of

opportunities for so long that it’s become marginalized,” he says, “But I think that’s more

changeable than people recognize.”

Nature 588, S170-S171 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03534-4

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Reproductive health, an editorially independent

supplement produced with the financial support of third parties. About this content.

References

1. Bearak, J. et al. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e1152–e1161 (2020).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility.

Fertil. Steril. 65, 821–829 (1996).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

3. Behre, H. M. et al. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 4779–4788 (2016).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

4. Anawalt, B. D. et al. Andrology 7, 878–887 (2019).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

Download references

Latest on:

Health care Public health Biotechnology

Free school meals to

alleviate global hunger

CORRESPONDENCE | 12 JUL 22

Who to vaccinate first? Major wildlife report

A peek at decision- struggles to tally

making in a pandemic humanity’s

COMMENT | 12 JUL 22

exploitation of species

NEWS | 12 JUL 22

Jobs

Multiple Positions Open in Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang

University School of Medicine(ZJUSS)

Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine(ZJUSS)

Hangzhou, China

Postdoctoral position: Quantum mechanical descriptors for improved prediction of

ADMET molecular properties

University of Luxembourg

Luxembourg, Luxembourg

Research & Development Specialist for Neurometabolic Disease Modeling in Zebrafish

University of Luxembourg

Luxembourg, Luxembourg

R&D specialist in a research-to-market project based on recent materials physics

breakthroughs

University of Luxembourg

Luxembourg, Luxembourg

Nature (Nature) ISSN 1476-4687 (online) ISSN 0028-0836 (print)

Nature portfolio

About us Press releases Press office Contact us

Discover content Publishing policies Author & Researcher services Libraries & institutions

Journals A-Z Nature portfolio policies Reprints & permissions Librarian service & tools

Articles by subject Open access Research data Librarian portal

Nano Language editing Open research

Protocol Exchange Scientific editing Recommend to library

Nature Index Nature Masterclasses

Nature Research Academies

Research Solutions

Advertising & partnerships Career development Regional websites Legal & Privacy

Advertising Nature Careers Nature Africa Privacy Policy

Partnerships & Services Nature Conferences Nature China Use of cookies

Media kits Nature events Nature India Manage cookies/Do not sell my data

Branded content Nature Italy Legal notice

Nature Japan Accessibility statement

Nature Korea Terms & Conditions

Nature Middle East California Privacy Statement

© 2022 Springer Nature Limited

You might also like

- Practice Test Community Health Nursing Set: CDocument8 pagesPractice Test Community Health Nursing Set: CAngelica Kaye BuanNo ratings yet

- Genie in Your GenesDocument15 pagesGenie in Your GenesMademoiselleBovary67% (6)

- Pastoral Aspects of HV Jan 2009Document83 pagesPastoral Aspects of HV Jan 2009JT23No ratings yet

- Human Genetic Enhancements Research PaperDocument12 pagesHuman Genetic Enhancements Research Paperapi-235903650No ratings yet

- Congenital Hip DislocationDocument2 pagesCongenital Hip DislocationKenNo ratings yet

- Mortality and Morbidity CHNDocument19 pagesMortality and Morbidity CHNPamela Ria HensonNo ratings yet

- Physiology of MenstrationDocument33 pagesPhysiology of MenstrationYiel Ellie Balase Moldin100% (1)

- Better Birth ControlDocument1 pageBetter Birth ControlMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Reproductive HealthDocument1 pageReproductive HealthMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Research Round-Up: Reproductive HealthDocument1 pageResearch Round-Up: Reproductive HealthMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Science Facts On The RH BillDocument1 pageScience Facts On The RH BillCFC FFLNo ratings yet

- Science Facts On The RH Bill - With SolutionsDocument1 pageScience Facts On The RH Bill - With SolutionsraulnidoyNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument13 pagesReportapi-663135887No ratings yet

- ReportDocument13 pagesReportapi-663410827No ratings yet

- Strengthening Society With ContraceptionDocument1 pageStrengthening Society With ContraceptionMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- RH BillDocument13 pagesRH BillDr. Liza ManaloNo ratings yet

- Scholarly Final Paper 2Document2 pagesScholarly Final Paper 2maryNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 10 00351Document7 pagesFpsyg 10 00351forensik24mei koasdaringNo ratings yet

- Hope, Burden or Risk FPDocument24 pagesHope, Burden or Risk FPDolores GalloNo ratings yet

- !!! - Ter Keurst Et Al 2015 Women's Intentions To Use Fertility Preservation To Prevent Age-Related Fertility DeclineDocument12 pages!!! - Ter Keurst Et Al 2015 Women's Intentions To Use Fertility Preservation To Prevent Age-Related Fertility DeclineStela PenkovaNo ratings yet

- Comandante, Josric T. - Position PaperDocument6 pagesComandante, Josric T. - Position PaperJosric ComandanteNo ratings yet

- Artículo Farmacología Anticonceptivo MasculinoDocument3 pagesArtículo Farmacología Anticonceptivo MasculinoMichelle RojoNo ratings yet

- Infertility Project PDFDocument11 pagesInfertility Project PDFSunil KumarNo ratings yet

- Group 6 - DNA Fragmentation.Document11 pagesGroup 6 - DNA Fragmentation.mangalover14344No ratings yet

- Obsos 3Document7 pagesObsos 3Depri AndreansyaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On UtiDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Utigz8qarxz100% (1)

- Piis0002937809020031 PDFDocument6 pagesPiis0002937809020031 PDFRaisa AriesthaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Oral Contraceptives on Women's Roles in SocietyDocument10 pagesEffects of Oral Contraceptives on Women's Roles in SocietyDorotea ŠvrakaNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument12 pagesResearch Paperapi-661467979No ratings yet

- Wiley Protocol Consumer Newsletter September 2009Document3 pagesWiley Protocol Consumer Newsletter September 2009WileyProtocolNo ratings yet

- Advanced Paternal AgeDocument5 pagesAdvanced Paternal AgejuanNo ratings yet

- Birth Control Hormones in Water - Separating Myth From FactDocument4 pagesBirth Control Hormones in Water - Separating Myth From Factnikola_sakacNo ratings yet

- BIOETHICS: A STUDY OF ETHICAL ISSUES IN BIOLOGY AND MEDICINEDocument42 pagesBIOETHICS: A STUDY OF ETHICAL ISSUES IN BIOLOGY AND MEDICINERaven Evangelista CanaNo ratings yet

- Article 8 - ExportDocument2 pagesArticle 8 - Exportapi-296608395No ratings yet

- Jama Oconnor 2019 Us 180028 PDFDocument14 pagesJama Oconnor 2019 Us 180028 PDFDiana MendozaNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Attitude of Tribal Woman Towards Re Productive HealthDocument4 pagesA Study On The Attitude of Tribal Woman Towards Re Productive HealthEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Vo-Sinh-Nam Male Infertility - 0Document5 pagesVo-Sinh-Nam Male Infertility - 0Thanh NguyNo ratings yet

- Javon WitherspoonDocument6 pagesJavon Witherspoonapi-445367279No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Embryonic Stem Cell ResearchDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Embryonic Stem Cell Researchlaurasmithkansascity100% (2)

- Proposal Presentation SanaDocument6 pagesProposal Presentation SanaGazala ParveenNo ratings yet

- Birth Control Pills Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesBirth Control Pills Thesis Statementsabrinahendrickssalem100% (2)

- 9.contraceptive Sterilization Global Issues and TrenDocument3 pages9.contraceptive Sterilization Global Issues and Trenmicheletl22No ratings yet

- Research Paper 3Document12 pagesResearch Paper 3api-534311862No ratings yet

- 2001 107 562-573 Donald E. Greydanus, Dilip R. Patel and Mary Ellen RimszaDocument14 pages2001 107 562-573 Donald E. Greydanus, Dilip R. Patel and Mary Ellen RimszaNurse AlzahraNo ratings yet

- Potential New Function of Lymphatic System Revealed: Delivering Excellence in Complementary MedicineDocument1 pagePotential New Function of Lymphatic System Revealed: Delivering Excellence in Complementary MedicinePaola MeliNo ratings yet

- Private and Public EugenicsDocument12 pagesPrivate and Public EugenicsAnindita MajumdarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Test Tube BabyDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Test Tube Babyiangetplg100% (1)

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Assisted Reproduction and The Impact On SocietyDocument4 pagesThe Advantages and Disadvantages of Assisted Reproduction and The Impact On SocietyUsman MohsinNo ratings yet

- Fetal TissueDocument2 pagesFetal Tissueapi-243325306No ratings yet

- Conttraception AssignmentDocument10 pagesConttraception AssignmentMaria Hazel AbayaNo ratings yet

- Ebp - FinalDocument28 pagesEbp - Finalapi-402946078No ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper About Birth ControlDocument5 pagesSample Research Paper About Birth Controlebvjkbaod100% (1)

- Mandatory Vaccines - Evan StallardDocument5 pagesMandatory Vaccines - Evan Stallardapi-534384348No ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument8 pagesResearch Paperapi-512310570No ratings yet

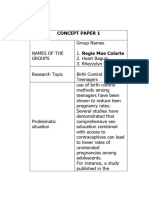

- CONCEPT-PAPER-1-REGIEMAEDocument14 pagesCONCEPT-PAPER-1-REGIEMAEcuesta.renelynNo ratings yet

- Edrv 0735Document28 pagesEdrv 0735Nofianti anggia putriNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0015028203005776Document15 pagesPi Is 0015028203005776InTan PermataNo ratings yet

- Genetic Engineering - UploadDocument17 pagesGenetic Engineering - UploadJan Albert AlavarenNo ratings yet

- The Use of Contraceptives in Nigeria: Benefits, Challenges and Probable SolutionsDocument13 pagesThe Use of Contraceptives in Nigeria: Benefits, Challenges and Probable SolutionsShaguolo O. JosephNo ratings yet

- A Study To Assess The Knowledge and Awareness.30Document9 pagesA Study To Assess The Knowledge and Awareness.30van deNo ratings yet

- Stem Cell Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesStem Cell Thesis Topicscindywootenevansville100% (2)

- Use Only: Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices Among Working-Class Women in Osun State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesUse Only: Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices Among Working-Class Women in Osun State, Nigeriahenri kaneNo ratings yet

- Getting Pregnant in the 1980s: New Advances in Infertility Treatment and Sex PreselectionFrom EverandGetting Pregnant in the 1980s: New Advances in Infertility Treatment and Sex PreselectionNo ratings yet

- How To Stop Mother-To-Child Transmission of Hepatitis BDocument1 pageHow To Stop Mother-To-Child Transmission of Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Robots Rise To Meet The Challenge of Caring For Old PeopleDocument1 pageRobots Rise To Meet The Challenge of Caring For Old PeopleMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Does The Human Lifespan Have A Limit?Document1 pageDoes The Human Lifespan Have A Limit?MicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- How The COVID-19 Pandemic Might Age UsDocument1 pageHow The COVID-19 Pandemic Might Age UsMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- AgeingDocument1 pageAgeingMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- The Global Fight Against Hepatitis B Is Benefitting Some Parts of The World More Than OthersDocument1 pageThe Global Fight Against Hepatitis B Is Benefitting Some Parts of The World More Than OthersMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Research Round-Up: Hepatitis BDocument1 pageResearch Round-Up: Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Unmet Need For A Functional Cure For Chronic Hepatitis BDocument1 pageAddressing The Unmet Need For A Functional Cure For Chronic Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Support For LGBTQ+ People in Later LifeDocument1 pageSupport For LGBTQ+ People in Later LifeMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Facing The Challenge of Eliminating Hepatitis BDocument1 pageFacing The Challenge of Eliminating Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Africa's Struggle With Hepatitis BDocument1 pageAfrica's Struggle With Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Charting A New Frontier in Chronic Hepatitis B Research To Improve Lives WorldwideDocument1 pageCharting A New Frontier in Chronic Hepatitis B Research To Improve Lives WorldwideMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Destigmatizing Hepatitis BDocument1 pageDestigmatizing Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Why Hepatitis B Hits Aboriginal Australians Especially HardDocument1 pageWhy Hepatitis B Hits Aboriginal Australians Especially HardMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B and The Liver Cancer EndgameDocument1 pageHepatitis B and The Liver Cancer EndgameMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Developing A Cure For Chronic Hepatitis B Requires A Fresh ApproachDocument1 pageDeveloping A Cure For Chronic Hepatitis B Requires A Fresh ApproachMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Simplify Access To Hepatitis B CareDocument1 pageSimplify Access To Hepatitis B CareMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Developing A Cure For Chronic Hepatitis B Requires A Fresh ApproachDocument1 pageDeveloping A Cure For Chronic Hepatitis B Requires A Fresh ApproachMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- How To Stop Mother-To-Child Transmission of Hepatitis BDocument1 pageHow To Stop Mother-To-Child Transmission of Hepatitis BMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Learning Over A LifetimeDocument1 pageLearning Over A LifetimeMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B: Related ArticlesDocument1 pageHepatitis B: Related ArticlesMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Unpicking The Link Between Smell and MemoriesDocument1 pageUnpicking The Link Between Smell and MemoriesMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Robots To TouchDocument1 pageTeaching Robots To TouchMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- The Science of Smell Steps Into The SpotlightDocument1 pageThe Science of Smell Steps Into The SpotlightMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Restoring Smell With An Electronic NoseDocument1 pageRestoring Smell With An Electronic NoseMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Breaking Into The Black Box of Artificial IntelligenceDocument1 pageBreaking Into The Black Box of Artificial IntelligenceMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Miniature Medical Robots Step Out From Sci-FiDocument1 pageMiniature Medical Robots Step Out From Sci-FiMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Olfactory Receptors Are Not Unique To The NoseDocument1 pageOlfactory Receptors Are Not Unique To The NoseMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- The Science Behind COVID's Assault On SmellDocument1 pageThe Science Behind COVID's Assault On SmellMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Modern TCM: Enter The Clinic - NatureDocument1 pageModern TCM: Enter The Clinic - NatureMicheleFontanaNo ratings yet

- Common Disorders of the Vagina and CervixDocument4 pagesCommon Disorders of the Vagina and CervixLOUISE VENICE PEREZ CIDNo ratings yet

- Ems NC Iii - SagDocument10 pagesEms NC Iii - SagJaypz DelNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Risk of Bleeding During PregnancyDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan for Risk of Bleeding During PregnancybananakyuNo ratings yet

- Human ReproductionDocument53 pagesHuman ReproductionMahdeldien WaleedNo ratings yet

- Complete Blood CountDocument5 pagesComplete Blood CountShella CondezNo ratings yet

- Topic 7 NURSE MIDWIFERY PRACTITIONER NavjotDocument7 pagesTopic 7 NURSE MIDWIFERY PRACTITIONER NavjotSimon JosanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On Standardization of Exclusions in Health Insurance ContractsDocument14 pagesGuidelines On Standardization of Exclusions in Health Insurance Contractsaarchi aarchiNo ratings yet

- NFHS-5 Interviewer Manual - EngDocument182 pagesNFHS-5 Interviewer Manual - EngDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- Associations of education level and dietary factors with anemia in pregnant womenDocument8 pagesAssociations of education level and dietary factors with anemia in pregnant womenAndi RahmadNo ratings yet

- A Short History of The Real-Time Ultrasound ScannerDocument14 pagesA Short History of The Real-Time Ultrasound ScannerBmet ConnectNo ratings yet

- Facts About PregnancyDocument18 pagesFacts About PregnancyRonalyn AsunioNo ratings yet

- The Role of Lifestyle in Male Infertility: Diet, Physical Activity, and Body HabitusDocument10 pagesThe Role of Lifestyle in Male Infertility: Diet, Physical Activity, and Body HabitusSantiago CeliNo ratings yet

- Asexual Reproduction TypesDocument28 pagesAsexual Reproduction TypesPrateek RanaNo ratings yet

- Preventive PaediatricsDocument24 pagesPreventive Paediatricsbiswaspritha.18No ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 02555 v2Document31 pagesIjerph 18 02555 v2Julia Mar Antonete Tamayo AcedoNo ratings yet

- VTE in Pregnancy 2021 by DR AmanuelDocument43 pagesVTE in Pregnancy 2021 by DR AmanuelAmanuel We/gebriel100% (1)

- Drug StudyDocument7 pagesDrug StudyAlhadzra AlihNo ratings yet

- Not For General Distribution: Reading Sub-Test - Text Booklet: Part ADocument24 pagesNot For General Distribution: Reading Sub-Test - Text Booklet: Part AAlwin BrightNo ratings yet

- Ananda Desy Rahmadhany A.Md - KebDocument2 pagesAnanda Desy Rahmadhany A.Md - Kebananda desy desyNo ratings yet

- Four Phases of Parturition: Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4Document2 pagesFour Phases of Parturition: Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4Elizer Mario Pre Raboy100% (1)

- Physiotherapy in Obstetrics GynaecologyDocument90 pagesPhysiotherapy in Obstetrics Gynaecologyمركز ريلاكس للعلاج الطبيعيNo ratings yet

- Male Inf Overview and Causeleaver2016Document6 pagesMale Inf Overview and Causeleaver2016annisa habibulloh100% (1)

- Nurse Licensure Examination Review Class: Prepared By: Roselyn Senas Pacardo, Man, MM, RN, RMDocument48 pagesNurse Licensure Examination Review Class: Prepared By: Roselyn Senas Pacardo, Man, MM, RN, RMtachycardia01No ratings yet

- Chlorhexidine-Alcohol Versus Povidone-Iodine For Skin Preparation Before Elective Cesarean Section A Prospective Observational StudyDocument6 pagesChlorhexidine-Alcohol Versus Povidone-Iodine For Skin Preparation Before Elective Cesarean Section A Prospective Observational StudyjohnturpoNo ratings yet

- Expanded Maternity LeaveDocument1 pageExpanded Maternity LeaverbNo ratings yet

- Labor and Delivery MedicationsDocument10 pagesLabor and Delivery MedicationsLuis RiveraNo ratings yet