Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cryptocurrency Is Shit

Uploaded by

cimotaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cryptocurrency Is Shit

Uploaded by

cimotaCopyright:

Available Formats

Current Affairs

SEARCH SIGN IN

A Magazine of Politics and Culture

MAGAZINE INDEX PODCAST SHOP DONATE GALLERY SUBSCRIBE

Why This Computer

Scientist Says All

Cryptocurrency

Should “Die in a

Fire”

UC-Berkeley’s Nicholas Weaver has been studying

cryptocurrency for years. He thinks it’s a terrible idea

that will end in disaster.

Current Affairs filed 13 May 2022 in E C O N O M I C S

D

espite being hyped in expensive Super

Bowl ads, cryptocurrency is now having a

difficult moment. As the New York Times

reports, “the crypto world went into a full

meltdown this week in a sell-off that

graphically illustrated the risks of the

experimental and unregulated digital

currencies.” One of cryptocurrency’s most vocal skeptics is Nicholas

Weaver, senior staff researcher at the International Computer Science

Institute and lecturer in the computer science department at UC

Berkeley. Weaver has studied cryptocurrencies for years. Speaking with

Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson, Prof. Weaver explains

why he views the much-hyped technology with such antipathy. He

argues that cryptocurrency is useless and destructive, and should “die in a

fire.”

The interview transcript has been lightly edited for grammar and

clarity.

NATHAN J. ROBINSON:

Here’s a quote by you from 2018:

Cryptocurrencies, although a seemingly interesting idea, are simply

not fit for purpose. They do not work as currencies, they are grossly

inefficient, and they are not meaningfully distributed in terms of

trust. Risks involving cryptocurrencies occur in four major areas:

technical risks to participants, economic risks to participants, systemic

risks to the cryptocurrency ecosystem, and societal risks.

In a 2022 lecture about cryptocurrency on YouTube, you are even

more blunt and harsh:

This is a virus. Its harms are substantial. It has enabled billion dollar

criminal enterprises. It has enabled venture capitalists to do securities

fraud as their business. It has sucked people in. So either avoid it or

help me make it die in a fire.

But perhaps before we get to your justifications for these verdicts,

you could start by telling us what you think is the best way for the

average person to begin to think about what a cryptocurrency is.

NICHOLAS WEAVER:

Well, I’d start with what it’s supposed to be in theory. So in theory, it’s

supposed to be a way of doing payments with no intermediary. So the

idea is that if Alice wants to pay Bob a bet for 200 quatloos…

ROBINSON:

Hang on, you’ve dropped a word that isn’t a real word. Quatloos is a

fictional currency?

WEAVER:

It’s actually specifically a Star Trek reference. So if you want to gamble

with your imaginary currency, there should be no intermediary that is

responsible for executing the transfer. It’s just direct peer to peer

electronic cash. Or at least that’s the idea.

Now the problem is: how do you know who has what balance?

Electronic cash is actually something we’ve had for decades now. If I want

to transfer you money, I use PayPal or M-Pesa or Visa or a wire transfer or

this or that. Those all have a central intermediary. And there’s a

disadvantage of central intermediaries: They don’t like drug dealers. So as

a money transmitter, you are under legal obligations to block a lot of

known bad activity.

With cryptocurrencies, the idea is, let’s eliminate the notion of the

intermediary by making our balances public, but pseudonymous. So you’re

no longer you, you are just some long sequence of random-looking

numbers. And let’s create a ledger in the town square so that everybody’s

bank balance is public in the town square, but only identified by the

pseudonyms.

So for Alice to pay off her wager, she writes a check: “I, Alice’s

Random Pseudonymity, pay Bob’s Random Pseudonymity 200 quatloos.

Signed, Alice’s Random Pseudonymity.” Bob then checks to make sure

that Alice indeed has a balance, and if so, posts that check to the public

ledger. Now everybody knows that Alice is down 200, Bob is up 200.

And that’s how it works.

The problem is: how do you keep somebody from adding to the

ledger and faking stuff ? Well, that’s where the notion of the “mining”

comes in. What the miners are doing is literally wasting tons of electricity

to prove that the record is intact, because anybody who would want to

attack it has to waste that similar kind of electricity.

This creates a couple of real imbalances. Either they’re insecure or

they’re inefficient, meaning that if you don’t waste a lot of energy,

someone can rewrite history cheaply. If you don’t want people to rewrite

history, you have to be wasting tons and tons of resources 24/7, 365. And

that’s why Bitcoin burns as much power as a significant country.

ROBINSON:

So this criticism that you hear about Bitcoin, that it uses the energy of a

small to mid-sized country, that is true? You point out in your YouTube

lecture that there are a number of ways that the enthusiasts of Bitcoin

make excuses for this. They say “Well, it’s actually clean” or “It’s not too

much of a problem.” But it’s actually very, very wasteful.

WEAVER:

Yes. The biggest one is “this incentivizes green power.” Which it does in

the same way that a whole bunch of random shootings would incentivize

bulletproof vests.

But wait, it’s worse! The problem with the Global Public Square is

that it is a single, limited entity, and you have only so much you can add

to it at any given time. So Bitcoin burns that much of the world’s

electricity to be able to process somewhere between three to seven

transactions per second across the entire world.

ROBINSON:

That’s not many.

WEAVER:

It’s not many. And worse, it never could work for payments. So we’ve seen

waves come and go of companies saying “We’ll accept payments in

Bitcoin.” They’re lying. Because they aren’t actually accepting payments

in Bitcoin. They are using a service that allows them to price in dollars,

presents Bitcoin to the customer, transfers the Bitcoin, turns it into

dollars, and so the merchant is getting actual money. Which means if the

system has to balance and you want to buy with Bitcoin and you don’t

have Bitcoin, you have to convert dollars to Bitcoin. And this is, by

design, a horribly expensive process, because Bitcoin and the

cryptocurrencies are fundamentally incompatible with modern finance.

Modern finance has this rule that anything electronic needs to be

reversible for short periods of time. This allows an undo in case of fraud.

Have you had your credit card compromised before? I’ve had my credit

card numbers stolen a couple of times. The amount of money I lost is

zero. Because we have both good fraud protection and good ability to

reverse transactions. That does not exist in the cryptocurrency space. If

your cryptocurrency wallet is compromised, all your apes are fudged.

ROBINSON:

All your what, sorry?

WEAVER:

Your apes are fudged. Because the cryptocurrencies are often used for

buying these “non-fungible tokens” that have pictures of ugly little apes.

They just get liberated. But the result is, you cannot store cryptocurrency

on an internet-connected computer. Because what will happen is, if your

computer ever gets compromised, all your money gets stolen and there’s

nothing you can do about it.

And that’s a fundamental problem. But it just doesn’t work for

payments because of that throughput limit. And the volatility means you

get people converting it to real money. And so what is it good for?

Well, there are classes of payments that the intermediaries don’t

allow. The big ones are drug dealing, child sexual abuse material, and

ransoms. As a consequence, the cryptocurrency actually used for

payments is really only used seriously for: ransomware payments, where

companies have to pay $10 million. Drug deals—drug dealers hate it, but

it’s the only game in town. And we’ve had cases of websites selling child

exploitation material paid with Bitcoin.

And the reason I’ve gotten so sour on the cryptocurrency space is

the ransomware. It’s doing tens to hundreds of billions of dollars worth

of damage to the global economy. And it only exists because people can

pay in Bitcoin.

ROBINSON:

How does ransomware work, for people who aren’t familiar?

WEAVER:

So the way it works is that some bad guys in Russia break into, say,

Colonial Pipeline. They encrypt all the data and say “Hey, Colonial

Pipeline, pay me 5 million bucks or your data’s gone forever.” And

Colonial Pipeline pays the 5 million bucks and is offline for a while

anyway, and there are gas disruptions on the East Coast.

That exists only because there’s the ransomware payment method

of cryptocurrency. Because the alternatives are cash or bank transfers.

The banks will not allow payments of 5 million bucks to known

criminals in Russia. (Gee, I wonder why.) And if the known criminals in

Russia want to pick up a $5 million block of cash, well, that’s a 50

kilogram suitcase that they’re going to have to pick up, and when they go

to pick it up they might just get a .308 caliber gift courtesy of the U.S.

Marines. And so Bitcoin is the only game in town for them.

So it doesn’t work for payments. And it doesn’t work economically

either. It’s effectively a giant self-assembled Ponzi scheme. You hear about

people making money in Bitcoin or cryptocurrency. They only make

money because some other sucker lost more. This is very different from

the stock market.

I’m a savvy investor, and by “savvy investor,” I mean I put my

money into index funds and ignore it for several years. During that time,

there are dividends and share buybacks where the companies put their

profits into me. I then eventually sell it to somebody else. And my gain is

not just the difference between what I bought it for and what somebody

else bought it for, but that plus the benefit of all the dividends and

interest.

So the stock market and the bond market are a positive-sum game.

There are more winners than losers. Cryptocurrency starts with zero-

sum. So it starts with a world where there can be no more winning than

losing. We have systems like this. It’s called the horse track. It’s called the

casino. Cryptocurrency investing is really provably gambling in an

economic sense. And then there’s designs where those power bills have to

get paid somewhere. So instead of zero-sum, it becomes deeply negative-

sum.

Effectively, then, the economic analogies are gambling and a Ponzi

scheme. Because the profits that are given to the early investors are

literally taken from the later investors. This is why I call the space overall,

a “self-assembled” Ponzi scheme. There’s been no intent to make a Ponzi

scheme. But due to its nature, that is the only thing it can be.

ROBINSON:

Is that why you see the pile of Super Bowl ads for investing in

cryptocurrency? Because the people who are the early investors need to

keep finding new suckers and trying to convince people that putting their

retirement savings into cryptocurrency is a sound idea?

WEAVER:

Yep. Because it’s a self-created pyramid scheme, you have to keep getting

new suckers in. As soon as the number of suckers dries up, it collapses.

And because it’s not zero-sum, but deeply negative-sum, there are

actually a lot of mechanisms that can cause it to collapse suddenly to

zero. We saw this just the other day with the Terra stablecoin and the

Luna side token. This was basically another Ponzi scheme implemented

in the larger space of Ponzi schemes.

So the idea is, you had these two cryptocurrencies, “Terra” and

“Luna.” Terra is supposed to be tied one-to-one with the U.S. dollar. Luna

can float around. If Terra costs more than $1, you can turn Luna into

Terra and make a profit, while if Terra costs less than $1 you can turn

Terra into Luna and make a profit. But this only works as long as the

value of Luna is greater than the value of Terra.

Now, why would you use Terra at all? Well, one, this is a stablecoin

and these are necessary for the gambling aspects of cryptocurrency. They

act basically as casino chips, because almost all of the cryptocurrency

exchanges are really cut off from the banking system. But the other

reason is, because you could take your Terra stablecoin, put it in a lending

protocol that was created by the creators of Luna and Terra and get a 20%

rate of return paid for by Luna and Terra, a.k.a. a Ponzi scheme.

And so billions of dollars of notional value went into this Ponzi

scheme. And the backing of Luna just slowly crept down, down, down.

And then all of a sudden, there was a crisis of faith. People no longer

believed that Terra was worth $1. It pegged to 95 cents. The folks behind

Terra and Luna go “Everything’s fine. Nothing to see here.” And then it

collapsed amazingly quickly over the space of two to three days. And

we’re now at the point where the Terra stablecoin that was supposed to

be worth $1 is now worth 10 cents, and the Luna token has basically

gone down by 99.99%. And people keep finding out that just because

something’s gone down 95% doesn’t mean it can’t still go down another

95%.

ROBINSON:

What about the other major “stablecoin,” this “Tether”? Is that subject to

the same kinds of risks?

WEAVER:

Yes and no. It is subject to the same kind of risks, but it’s different. It

doesn’t have this algorithmic collapse model, but it does have the

potential for bank runs causing collapse, because it’s unbacked.

Tether is almost certainly what we’d call a “wildcat bank.” So, back

in the 1800s, we didn’t have the Federal Reserve. Do you ever wonder

why those pieces of paper in your pocket are technically called “bank

notes”? It’s because the original model was not the government issuing

pieces of paper. The government only issued coins. But heavy or bulky

coins are hard to deal with. So you take your coins to the local bank, and

they would give you a banknote, literally an IOU saying “if you want a

$1 gold coin, take this IOU back to the bank and you get this dollar gold

coin.”

What happened is, basically, fraudulent banks sprang up. They

were called wildcat banks because they’d often have animal pictures on

the bank notes. What they would do is take deposits and issue pieces of

paper, completely unbacked. And when state bank regulators would

come along, the wildcat banks would have barrels of coins that were fake.

All but the top layer was just junk, with a top layer of gold coins. Or

they’d cart around a barrel to all the branch offices just ahead of the

inspectors.

And Tether is clearly doing the same thing. Because if Tether was

backed by real money, this would mean that there is some $80 billion

worth of money from institutional savvy investors that wanted to invest

in the cryptocurrency space, but didn’t want to just buy in CoinBase. So

they had to go to this third party that has been caught lying about its

reserves, run by who-knows-who—the CEO is basically MIA. [Slate

reported in 2021 that he “hasn’t been seen in public in years.”] It keeps its

reserves in the Bahamas. Why would you invest that way? It’s just

complete nonsense.

So what’s really almost certainly happening with Tether is Tether

creates new Tether tokens, loans them to their big colleagues in the

cryptocurrency space—so Alameda Research and a couple of others like

that. Alameda Research provides IOUs so Tether says they’re backed by

loans. Then Alameda goes out and buys Bitcoin, driving up the price.

And now the Tether is backed by Bitcoin. And so Tether in the end is

backed by underlying cryptocurrency.

They refuse to get audited. [Bloomberg reported that Tether CFO,

an Italian former plastic surgeon, was “urged … to hire an accounting

firm to produce a full audit to reassure the public,” but “said Tether didn’t

need to go that far to respond to critics.”] They refuse to even do more

than the most basic attestation, which is literally “Here, accountant, sign

this.” We’re honest, Scout’s pledge. It’s just a house of cards. And the

problem is that when these houses of cards fail, they fail so

catastrophically and so swiftly that things go from being worth $1 to

being worth nothing in the space of three days.

ROBINSON:

I want to zoom out again to talk about cryptocurrency in general and go

back to some of the broad critiques you have. Is it accurate to summarize

what you were saying before as, essentially: There is no problem that

cryptocurrency solves, and to the extent that it is functional, it does

things worse than we can already do them with existing electronic

payment systems. To the extent it has advantages, the advantage is doing

crimes. And every other claim made for the superiority of cryptocurrency

as currency falls apart if you scrutinize it.

WEAVER:

Yes. So let’s take the cost of a transaction. The cost of a transaction in

cryptocurrency systemically is the amount being used to protect it. I

could build a system that would have the same throughput as Bitcoin,

three to seven transactions per second, but with a centralized trusted

entity. In fact, not even a centralized trusted entity. Ten trusted entities,

only six of which need to be honest, because I use a majority vote system.

I could do it on ten computers that look like this, that would burn as

much power as a light bulb.

ROBINSON:

For listeners and readers, he is holding up a tiny … uh, what is that?

WEAVER:

I am holding up a Raspberry Pi computer module. This entire computer

is like 50 bucks. So for 500 bucks worth of [computing power], I could

do the same functionality as Bitcoin, with just 10 named entities. Why

don’t I do this? Because those 10 named entities would have to follow

money laundering laws. And apart from getting a structure where the

named entities don’t follow money laundering laws, there’s no advantage

for the cryptocurrencies, despite burning nine orders of magnitude more

power.

ROBINSON:

One of the kind of jaw-dropping moments in your YouTube lecture is

when you show just how wasteful this is, how easily you could do the

exact same thing, and not have this pathetic three to seven transfers per

second all around the world.

You do note that it suggests that Elon Musk—who is touted for

the electric cars that are supposedly going to be an important

contribution to stopping climate change, but has invested billions of

dollars of Tesla’s money in Bitcoin—probably isn’t that serious or

consistent about reducing our carbon emissions.

WEAVER:

Phony Stark over there has a walking talking Dunning-Kruger syndrome

going and his investment in cryptocurrency is clearly one of those. The

cryptocurrency that he often highlights is Dogecoin. Dogecoin was a

literal joke invented in the early days of cryptocurrency about, “Hey, this

stuff is so stupid. Let’s make a coin about a meme of a talking dog.” The

You might also like

- Cryptrillionaire: A Beginner's Road Map to Generating Wealth with Bitcoin and Other Digital AssetsFrom EverandCryptrillionaire: A Beginner's Road Map to Generating Wealth with Bitcoin and Other Digital AssetsNo ratings yet

- Digital Money Demystified: Go From Cash to Crypto® Safely, Legally, and ConfidentlyFrom EverandDigital Money Demystified: Go From Cash to Crypto® Safely, Legally, and ConfidentlyNo ratings yet

- Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money that We Understand to Money that Understands UsFrom EverandBefore Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money that We Understand to Money that Understands UsNo ratings yet

- Digital Cash: The Unknown History of the Anarchists, Utopians, and Technologists Who Created CryptocurrencyFrom EverandDigital Cash: The Unknown History of the Anarchists, Utopians, and Technologists Who Created CryptocurrencyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Let's Meet Blockchain: Technology Changing for Working, Creating, and PlayingFrom EverandLet's Meet Blockchain: Technology Changing for Working, Creating, and PlayingNo ratings yet

- Bitcoin for Nonmathematicians:: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto PaymentsFrom EverandBitcoin for Nonmathematicians:: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto PaymentsNo ratings yet

- Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart ContractsFrom EverandAttack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart ContractsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Cryptocurrency Investment Handbook: How to Benefit from the Next Big Technology after the InternetFrom EverandCryptocurrency Investment Handbook: How to Benefit from the Next Big Technology after the InternetRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Cryptocurrency 101: Everything You Need to Know About Digital Currencies and Blockchain TechnologyFrom EverandCryptocurrency 101: Everything You Need to Know About Digital Currencies and Blockchain TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Decoding Tomorrow's Currency: An In-Depth Exploration of the Future of CryptocurrencyFrom EverandDecoding Tomorrow's Currency: An In-Depth Exploration of the Future of CryptocurrencyNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Finance for Women: Empowering Women Through CryptocurrencyFrom Everand21st Century Finance for Women: Empowering Women Through CryptocurrencyNo ratings yet

- Crypto Treasure Map: A Guide To Investing In Bitcoin And CryptocurrenciesFrom EverandCrypto Treasure Map: A Guide To Investing In Bitcoin And CryptocurrenciesNo ratings yet

- Mock 15Document13 pagesMock 15Alejandro Rengel BarragánNo ratings yet

- Eview: Book ReviewDocument3 pagesEview: Book ReviewElena AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrencies: Invest Wisely in the Most Profitable and Trusted Cryptocurrencies to Make MoneyFrom EverandCryptocurrencies: Invest Wisely in the Most Profitable and Trusted Cryptocurrencies to Make MoneyNo ratings yet

- Let's Make Some Money - R.MDocument39 pagesLet's Make Some Money - R.MKwame JordanNo ratings yet

- Getting Started with Cryptocurrency: An introduction to digital assets and blockchainFrom EverandGetting Started with Cryptocurrency: An introduction to digital assets and blockchainNo ratings yet

- 21CryptosMagazine 2018august PDFDocument100 pages21CryptosMagazine 2018august PDFhesiluNo ratings yet

- History, Future of NFTsDocument4 pagesHistory, Future of NFTsIshaq GbengaNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrency Remote Viewed Book Four: Cryptocurrency Remote Viewed, #4From EverandCryptocurrency Remote Viewed Book Four: Cryptocurrency Remote Viewed, #4No ratings yet

- Summary of Easy Money By Ben Mckenzie : Cryptocurrency, Casino Capitalism, and the Golden Age of FraudFrom EverandSummary of Easy Money By Ben Mckenzie : Cryptocurrency, Casino Capitalism, and the Golden Age of FraudNo ratings yet

- Let Them Eat Crypto: The Blockchain Scam That's Ruining the WorldFrom EverandLet Them Eat Crypto: The Blockchain Scam That's Ruining the WorldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Session_12_Reading_2Document11 pagesSession_12_Reading_2Rana AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Crypto Uncovered: The Evolution of Bitcoin and the Crypto Currency MarketplaceFrom EverandCrypto Uncovered: The Evolution of Bitcoin and the Crypto Currency MarketplaceNo ratings yet

- The Only Crypto Story You Need - Sal BayatDocument8 pagesThe Only Crypto Story You Need - Sal BayatA. O. GilmoreNo ratings yet

- The Executive Guide to Blockchain: Using Smart Contracts and Digital Currencies in your BusinessFrom EverandThe Executive Guide to Blockchain: Using Smart Contracts and Digital Currencies in your BusinessNo ratings yet

- Blockchain & Crypto Use Cases 2024Document27 pagesBlockchain & Crypto Use Cases 2024hcsearch0897No ratings yet

- Rugpulls Genesis: Birth of Crypto's Vulnerabilities: Altcoin Pioneers: The Rise of Bitcoin's Competitors: Rugpulls Unveiled: Untangling the Web of Deceit in Early Crypto, #1From EverandRugpulls Genesis: Birth of Crypto's Vulnerabilities: Altcoin Pioneers: The Rise of Bitcoin's Competitors: Rugpulls Unveiled: Untangling the Web of Deceit in Early Crypto, #1No ratings yet

- Money, Magic, and How to Dismantle a Financial Bomb: Quantum Economics for the Real WorldFrom EverandMoney, Magic, and How to Dismantle a Financial Bomb: Quantum Economics for the Real WorldNo ratings yet

- Where Did All the Cash Go? The Digital Money World. Understanding CBDC and Cryptocurrency; Digital Money, Finance, Bitcoin, Crypto, Cryptocurrency, CBDC, Digital Currency, Money BookFrom EverandWhere Did All the Cash Go? The Digital Money World. Understanding CBDC and Cryptocurrency; Digital Money, Finance, Bitcoin, Crypto, Cryptocurrency, CBDC, Digital Currency, Money BookNo ratings yet

- The Sweet Life with Bitcoin: How I Stopped Worrying about Cryptocurrency and You Should Too!From EverandThe Sweet Life with Bitcoin: How I Stopped Worrying about Cryptocurrency and You Should Too!No ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide to Cryptocurrency: Navigating the World of Digital AssetsFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide to Cryptocurrency: Navigating the World of Digital AssetsNo ratings yet

- Crypto Millionaire Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Cryptocurrency SuccessFrom EverandCrypto Millionaire Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Cryptocurrency SuccessNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrency: Technical OverviewDocument10 pagesCryptocurrency: Technical OverviewnepretipNo ratings yet

- Monero 2Document29 pagesMonero 2Jon AldekoaNo ratings yet

- The Lost and Found GhostsDocument9 pagesThe Lost and Found GhostscimotaNo ratings yet

- The Raise Investment Club: Get Involved TodayDocument1 pageThe Raise Investment Club: Get Involved TodaycimotaNo ratings yet

- Techstart-Funds-Evaluation-Nispo-Impact-Assessment 2Document131 pagesTechstart-Funds-Evaluation-Nispo-Impact-Assessment 2cimotaNo ratings yet

- Iain's Naval GazerDocument3 pagesIain's Naval GazercimotaNo ratings yet

- FurukontakutoDocument9 pagesFurukontakutocimotaNo ratings yet

- Up The Coast OutlineDocument3 pagesUp The Coast OutlinecimotaNo ratings yet

- Performance Business - Assignment 1Document11 pagesPerformance Business - Assignment 1cimotaNo ratings yet

- Nor Gloom of NightDocument19 pagesNor Gloom of NightcimotaNo ratings yet

- Draft Digital StrategyDocument18 pagesDraft Digital StrategycimotaNo ratings yet

- Cancer Girls PostersDocument4 pagesCancer Girls PosterscimotaNo ratings yet

- ZombiDocument65 pagesZombicimotaNo ratings yet

- ZombiDocument65 pagesZombicimotaNo ratings yet

- Electric CarsDocument3 pagesElectric CarscimotaNo ratings yet

- Architect / Contract Administrator's Instruction: Estimated Revised Contract PriceDocument6 pagesArchitect / Contract Administrator's Instruction: Estimated Revised Contract PriceAfiya PatersonNo ratings yet

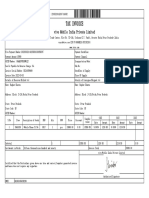

- Tax Invoice: Vivo Mobile India Private LimitedDocument1 pageTax Invoice: Vivo Mobile India Private LimitedRaghav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Business Strategy 101Document17 pagesMicrosoft Business Strategy 101Chinmay Chauhan50% (2)

- IRDA Project - Akanksha - LLMDocument9 pagesIRDA Project - Akanksha - LLMPULKIT KHANDELWALNo ratings yet

- Financail Accounting II Frist AssignmentDocument3 pagesFinancail Accounting II Frist AssignmentMuhammad Shahid KhanNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument1 pageDocumentVanessa GuardadoNo ratings yet

- Suarez, Francis - FORM 1 - 2008 PDFDocument2 pagesSuarez, Francis - FORM 1 - 2008 PDFal_crespoNo ratings yet

- Project InsuranceDocument13 pagesProject InsuranceRohan Raj MishraNo ratings yet

- Lee Mei Peng No 33 Jalan Delima 4A/Ks6 Bandar Parkland Pendamar 41200 KLANGDocument4 pagesLee Mei Peng No 33 Jalan Delima 4A/Ks6 Bandar Parkland Pendamar 41200 KLANGappleNo ratings yet

- Muzammil Qadeer Qureshi Phs Trainee Officer PAY ROLL NO: 21705-0Document25 pagesMuzammil Qadeer Qureshi Phs Trainee Officer PAY ROLL NO: 21705-0Muzammil QureshiiNo ratings yet

- Advanced Bank MamagementDocument43 pagesAdvanced Bank MamagementKarur KumarNo ratings yet

- Lululemon Financial AnalysisDocument14 pagesLululemon Financial Analysismrsammy100% (1)

- Quot PerusahaanDocument4 pagesQuot Perusahaanlady MonnNo ratings yet

- HOBA2019QUIZ1MCDocument10 pagesHOBA2019QUIZ1MCjasfNo ratings yet

- 1109021 (1)Document1 page1109021 (1)Cms Stl CmsNo ratings yet

- Characteristic Features of Financial InstrumentsDocument17 pagesCharacteristic Features of Financial Instrumentsmanoranjanpatra93% (15)

- Fr. Emmanuel Lemelson Letter To Congress Regarding LigandDocument9 pagesFr. Emmanuel Lemelson Letter To Congress Regarding LigandamvonaNo ratings yet

- 1 Van de Brug v. Philippine National BankDocument18 pages1 Van de Brug v. Philippine National BankHannah Keziah MoralesNo ratings yet

- Corporate ScorecardDocument36 pagesCorporate Scorecardgkohli79No ratings yet

- BIWS Atlassian 3 Statement Model - VFDocument8 pagesBIWS Atlassian 3 Statement Model - VFJohnny BravoNo ratings yet

- Iligan Institute of Technology: Mindanao State University Iligan CityDocument4 pagesIligan Institute of Technology: Mindanao State University Iligan Citylairah.mananNo ratings yet

- ECON8Document3 pagesECON8DayLe Ferrer AbapoNo ratings yet

- 3 Famous Personalities of The World - AssignmentDocument3 pages3 Famous Personalities of The World - AssignmentWajahat SheikhNo ratings yet

- Cadillac Ventures Inc.: Consolidated Financial Statements May 31, 2007 and 2006Document22 pagesCadillac Ventures Inc.: Consolidated Financial Statements May 31, 2007 and 2006CadVentNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting - Risk Analysis: Questions & AnswersDocument5 pagesCapital Budgeting - Risk Analysis: Questions & AnswersAyush BishtNo ratings yet

- What is Repo Rate, Reverse Repo Rate & their ImpactDocument4 pagesWhat is Repo Rate, Reverse Repo Rate & their ImpactRatnakar AletiNo ratings yet

- Partnership Formation GuideDocument5 pagesPartnership Formation GuideABCNo ratings yet

- RECENT AMENDMENTS TO COMPANIES ACT 2013Document39 pagesRECENT AMENDMENTS TO COMPANIES ACT 2013warner313No ratings yet

- The Current State of The Accounting ProfessionDocument2 pagesThe Current State of The Accounting ProfessionYuliana ArceNo ratings yet

- Ejemplo de Analisis Vertical y Horizontal Caso NikeDocument14 pagesEjemplo de Analisis Vertical y Horizontal Caso NikeDiego Blanco CastroNo ratings yet