Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Therapy Summur

Uploaded by

Abdulhakim ZekeriyaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Therapy Summur

Uploaded by

Abdulhakim ZekeriyaCopyright:

Available Formats

HYPERTENSION

Hypertension can be defined as a condition in which blood pressure (BP) is

elevated to a level likely to lead to adverse consequences. There is no clear-cut

blood pressure threshold separating normal blood pressure from high blood

pressure, with hypertension arbitrarily defined as a systolic blood pressure equal

to or greater than 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure equal to or greater

than 90 mmHg. The risk of complications is related to the degree to which blood

pressure is elevated

. • The World Health Organization has identified hypertension as the leading risk

factor for death worldwide. The complications of hypertension include stroke,

myocardial infarction, heart failure, renal failure and dissecting aortic aneurysm.

Modest reductions in blood pressure result in substantial reductions in the

relative risks of these complications.

• Hypertension should not be seen as a risk factor in isolation, and decisions on

management should not focus on blood pressure alone but on the total

cardiovascular risk present for an individual, which, in the absence of established

cardiovascular (CV) disease, should be calculated using a validated CV risk

calculator such as QRisk2.

• The diagnosis of hypertension should be based on the results of ambulatory

blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring, not on clinic

blood pressure readings

. • Non-pharmacological interventions are important and include weight

reduction, avoidance of excessive salt and alcohol, increased intake of fruit and

vegetables and regular physical activity. Other cardiovascular risk factors, such as

smoking, dyslipidaemia and diabetes, should be addressed.

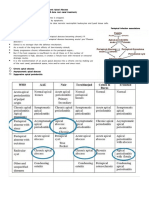

• Different antihypertensive drugs are available. Drug choice should aim to

maximise blood-pressure-lowering effectiveness and minimise patient side effects

. • The most appropriate choice of initial drug therapy depends on the age and

racial origin of the patient, as well as the presence of other medical conditions.

For patients younger than 55 years, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)

inhibitor is recommended as first-line treatment. For older patients and people of

black African or Caribbean origin of any age, a calcium channel blocker is an

appropriate initial choice. Most people need a combination of drugs to achieve

adequate blood pressure control.

HEART FAILURE

• Heart failure is a common condition that affects the quality of life, causing

fatigue, breathlessness and oedema. It often has a poor prognosis.

• Heart failure is a maladaptive condition with haemodynamic and

neurohormonal disturbances. Increased understanding of its pathophysiology and

the strength of the evidence base allow a rational approach to therapeutic

management.

• The aims of drug treatment are to control symptoms and improve survival. By

slowing disease progression, the aim is to maintain quality of life.

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, β-blockers and

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are first-line options in treating patients

with systolic dysfunction.

• Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are an alternative choice in patients

intolerant of or resistant to ACE inhibitors or mineralocorticoid receptor

antagonist therapy.

• Diuretics are used for symptomatic management of heart failure and are

combined with other agents in the treatment of systolic dysfunction.

• The use of sacubitril/valsartan should be considered under specialist advice in

patients with systolic dysfunction who have ongoing symptoms of heart failure

despite optimal therapy

. • Ivabradine should be considered under specialist advice in patients with

systolic dysfunction who have had a hospital admission for heart failure in the

preceding 12 months but have stabilised on standard therapy for at least 4 weeks.

• Digoxin may still have a role in improving symptoms and reducing the rate of

hospitalisation for patients with heart failure in sinus rhythm, but it has not been

demonstrated to affect mortality. The combination of hydralazine and nitrate may

still have a place for specific patients on the advice of a specialist.

• Heart failure is a condition in which integration of pharmaceutical care within

multidisciplinary models of patient care can improve clinical outcomes for

patients and contribute to the continuity of care

CHD

• Coronary heart disease (CHD) is common, often fatal and frequently

preventable.

• High dietary fat, smoking and sedentary lifestyle are risk factors for CHD and

require modification if present.

• Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity and personal

stress are also risk factors and require optimal management

. • Stable angina should be managed with nitrates for pain relief and β-blockers,

unless contraindicated, for long-term prophylaxis. Where β-blockers are

inappropriate, the use of calcium channel blockers and/or nitrates may be

considered

. • Acute coronary syndromes arise from unstable atheromatous plaques and

may be classified as to whether there is ST-elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI) or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

• ST elevation on the electrocardiogram (ECG) indicates an occluded coronary

artery and is used to determine treatment with fibrinolysis or primary

angioplasty.

• P atients with NSTEMI may have experienced myocardial damage, are at

increased risk of death and may benefit from a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

• Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the development of a ‘thrombus’, principally

containing fibrin and red blood cells, in the venous circulation. This most often

occurs as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the deep, as distinct from the

superficial, veins of the legs.

• If part of a thrombus in the venous circulation breaks off and enters the right

heart, it may become lodged in the pulmonary arterial circulation, causing

pulmonary embolism (PE).

• Combinations of sluggish blood flow and hypercoagulability are the most

common causes of VTE. Vascular injury is also a recognised causative factor.

• Treatment of VTE involves the use of anticoagulants and, in severe cases,

thrombolytic drugs

. • Anticoagulant therapy often involves an immediate-acting agent, such as

heparin, followed by maintenance treatment with an oral anticoagulant, such as

warfarin.

• Another option is the use of a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), also

sometimes known as a non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant/novel oral

anticoagulant (NOAC), with a marketing authorisation for such use. The use of

heparin in the early stages is not necessary with all of the DOACs, but

requirements change, and thus product literature should be consulted.

• Unfractionated heparins increase the rate of interaction of thrombin with

antithrombin III 1000-fold and prevent the production of fibrin from fibrinogen.

• Low-molecular-weight heparins inactivate factor Xa, have a longer half-life and

produce a more predictable response than unfractionated heparins

. • Warfarin is the most widely used coumarin because of potency, reliable

bioavailability and an intermediate half-life of elimination (36 hours).

• Warfarin consists of an equal mixture of two enantiomers, (R)- and (S)-

warfarins, that have different anticoagulant potencies and routes of metabolism.

The latter enantiomer is a much more potent anticoagulant.

• DOACs currently available include dabigatran etexilate, a direct thrombin

(factor IIa) inhibitor, and apixaban, e doxaban and rivaroxaban, which are direct

inhibitors of activated factor Xa.

Arterial thromboembolism

• Arterial thromboembolism is normally associated with vascular injury and

hypercoagulability

ACUTE MI IS THE COMON CAUSE OF arterial throbosis

• Arterial thromboembolism affecting the cerebral circulation results in either

transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) or, in more severe cases, cerebral infarction

(stroke).

• Arterial thrombosis is the development of a ‘thrombus’ consisting of platelets,

fibrin, red blood cells and white blood cells in the systemic circulation.

• An embolus may result in peripheral arterial occlusion, either in the lower

limbs or in the cerebral circulation (where it may cause thromboembolic stroke).

You might also like

- EKG Study GuideDocument45 pagesEKG Study GuideBrawner100% (6)

- Congestive Cardiac Failure GuideDocument47 pagesCongestive Cardiac Failure GuideRajesh Sharma100% (1)

- AAN 204 CARDIOVASCULAR NURSING COURSEWORKDocument118 pagesAAN 204 CARDIOVASCULAR NURSING COURSEWORKLucian CaelumNo ratings yet

- Atrial Fibrillation (AF)Document24 pagesAtrial Fibrillation (AF)farmasi_hm100% (1)

- 3.preoperative Patient Assessment and ManagementDocument76 pages3.preoperative Patient Assessment and Managementoliyad alemayehuNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of HypertensionDocument35 pagesDiagnosis and Management of HypertensionBasil Hussam100% (2)

- Essentials of Community Medicine - A Practical Approach PDFDocument487 pagesEssentials of Community Medicine - A Practical Approach PDFamarhadid70% (20)

- Management of Heart Failure: DR Ambakederemo TE Consultant Physician/cardiologist NduthDocument71 pagesManagement of Heart Failure: DR Ambakederemo TE Consultant Physician/cardiologist NduthPrincewill SeiyefaNo ratings yet

- Helene Deutsch, A Psychoanalysts Life (Lacanempdf)Document400 pagesHelene Deutsch, A Psychoanalysts Life (Lacanempdf)Carlos AugustoNo ratings yet

- Being in The World Selected Pa Ludwig BinswangerDocument388 pagesBeing in The World Selected Pa Ludwig BinswangerRamazan ÇarkıNo ratings yet

- National Clinical Pharmacy Service Implementation ManualDocument112 pagesNational Clinical Pharmacy Service Implementation ManualAbdulhakim ZekeriyaNo ratings yet

- Atrial Fibrillation: Discussed by - DR Kunwar Sidharth SaurabhDocument45 pagesAtrial Fibrillation: Discussed by - DR Kunwar Sidharth SaurabhKunwar Sidharth SaurabhNo ratings yet

- Introduction: A New Hierarchy of NeedsDocument5 pagesIntroduction: A New Hierarchy of Needsgun2 block100% (1)

- Heart FailureDocument28 pagesHeart FailureaparnaNo ratings yet

- CH 33 Key PointsDocument4 pagesCH 33 Key PointsKara Dawn MasonNo ratings yet

- Hypertension ESC Guideline 2018Document78 pagesHypertension ESC Guideline 2018Theresia KennyNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Guideline SummaryDocument12 pagesHypertension Guideline Summaryمصطفى ابراهيم سعيدNo ratings yet

- Diabetes and Peripheral Artery DiseaseDocument30 pagesDiabetes and Peripheral Artery DiseasedrbrdasNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease in The ElderlyDocument18 pagesCardiovascular Disease in The ElderlynfacmaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension: Silent KillerDocument28 pagesHypertension: Silent KilleribratiNo ratings yet

- Hypertension 2019 PDFDocument46 pagesHypertension 2019 PDFPNo ratings yet

- Medically Compromised Patient: HypertensionDocument32 pagesMedically Compromised Patient: Hypertensionمحمد عبدالهادي إسماعيلNo ratings yet

- Antihypertensive Drugs GuideDocument52 pagesAntihypertensive Drugs GuideAlan LealNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy - Hypertension - Dr. Mohammed KamalDocument85 pagesPharmacotherapy - Hypertension - Dr. Mohammed KamalMohammed KamalNo ratings yet

- Hypertension: Dr. Lucia Mazur-Nicorici Md. PHDDocument34 pagesHypertension: Dr. Lucia Mazur-Nicorici Md. PHDValerianBîcosNo ratings yet

- Hypertension GuideDocument25 pagesHypertension GuideBulborea MihaelaNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument45 pagesHypertensionM Farhad KhaniNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument10 pagesHypertensionaa zzNo ratings yet

- Hypertension: Hozan Jaza MSC Clinical Pharmacy College of Pharmacy 10/12/2020Document81 pagesHypertension: Hozan Jaza MSC Clinical Pharmacy College of Pharmacy 10/12/2020Alan K MhamadNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Agents PDFDocument118 pagesCardiovascular Agents PDFgherlethrNo ratings yet

- Diabetes HypertensionDocument29 pagesDiabetes HypertensionAnimesh PaulNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument58 pagesHypertensionSHAHALOMGIR AHMEDNo ratings yet

- Stroke Prevention and Management Guideline SummaryDocument24 pagesStroke Prevention and Management Guideline Summarynisha24100% (1)

- Hypertension: Prepared By: Dr. Shadab Kashif R.PH, M.SC (UK)Document18 pagesHypertension: Prepared By: Dr. Shadab Kashif R.PH, M.SC (UK)Ahmad Jamal HashmiNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument10 pagesDocumentMulhma AlharbiNo ratings yet

- Management of HypertensionDocument67 pagesManagement of Hypertensionainzahir94No ratings yet

- 3 HypertensionDocument26 pages3 Hypertensionsamar yousif mohamedNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading 2Document14 pagesJurnal Reading 2Riko KuswaraNo ratings yet

- Increased Arterial Blood PressureDocument25 pagesIncreased Arterial Blood PressureAjmalNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy of HypertensionDocument52 pagesPharmacotherapy of HypertensionDrVinod Kumar Goud VemulaNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology: Cardiovascular System Dr. Maen DweikDocument38 pagesPathophysiology: Cardiovascular System Dr. Maen DweikshoibyNo ratings yet

- Heartfailurepptsam 170511135108Document48 pagesHeartfailurepptsam 170511135108enam professorNo ratings yet

- Myocardial InfarctionDocument5 pagesMyocardial InfarctionNikki MacasaetNo ratings yet

- Ch. 32 - Hypertension - EditedDocument43 pagesCh. 32 - Hypertension - Editedمحمد الحواجرةNo ratings yet

- Hypertension HTNDocument42 pagesHypertension HTNpeter dymonNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument14 pagesHypertensiondrraziawardakNo ratings yet

- B HypertensionDocument15 pagesB Hypertensionabotawfeq abojalilNo ratings yet

- تقرير ضغط الدمDocument10 pagesتقرير ضغط الدمlyh355754No ratings yet

- Resumen The Seventh Report of The JointDocument4 pagesResumen The Seventh Report of The JointMARIANA GARCIA LOPEZNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research: Hypertension ManagementDocument4 pagesClinical Research: Hypertension ManagementJay Linus Rante SanchezNo ratings yet

- Farmakoterapi StrokeDocument33 pagesFarmakoterapi StrokeMuhammad Aldi SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest: DiscussionDocument19 pagesSudden Cardiac Arrest: DiscussionIza Singson-CristobalNo ratings yet

- CVS DOs RevisedDocument88 pagesCVS DOs RevisedTaate MohammedNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive CrisisDocument60 pagesHypertensive CrisisDzikrul Haq KarimullahNo ratings yet

- Osamah Ischemic StrokeDocument37 pagesOsamah Ischemic Strokejana.alngNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Considerations in Hypertensive Patient: Abhishikth Abraham Varghese Final Year Part 1 180020531Document21 pagesOral Health Considerations in Hypertensive Patient: Abhishikth Abraham Varghese Final Year Part 1 180020531Abhishikth VargheseNo ratings yet

- Atrial FibrillationDocument50 pagesAtrial Fibrillationkapil khanalNo ratings yet

- End-Stage Heart Disease Management and Palliative Care GuidelinesDocument44 pagesEnd-Stage Heart Disease Management and Palliative Care GuidelinesCyrille AgnesNo ratings yet

- Arrhythimas 6Document38 pagesArrhythimas 6غفران هيثم خليلNo ratings yet

- Kee: Pharmacology, 8th EditionDocument5 pagesKee: Pharmacology, 8th EditionLondera BainNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Lecture3: Pharmacological TreatmentDocument25 pagesHypertension Lecture3: Pharmacological TreatmentRam NiwasNo ratings yet

- Neurologic Function Cerebrovascular DisordersDocument15 pagesNeurologic Function Cerebrovascular DisordersBalilea, Derwin Stephen T.No ratings yet

- The Overview of Hypertension 2009Document50 pagesThe Overview of Hypertension 2009YeniNo ratings yet

- Anti-Hypertensive 2Document49 pagesAnti-Hypertensive 2pushpaNo ratings yet

- Medical Nutrition Therapy For Cardiovascular Disease 2013Document30 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy For Cardiovascular Disease 2013ashry909100% (1)

- Unveiling the Unseen: A Journey Into the Hearts Labyrinth SeanFrom EverandUnveiling the Unseen: A Journey Into the Hearts Labyrinth SeanNo ratings yet

- Physical Assi1Document26 pagesPhysical Assi1Abdulhakim ZekeriyaNo ratings yet

- Cology PageDocument4 pagesCology PageAbdulhakim ZekeriyaNo ratings yet

- History of Drug Discovery 1Document7 pagesHistory of Drug Discovery 1Brent FontanillaNo ratings yet

- Histology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Apical AbscessDocument3 pagesHistology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Apical AbscessPrince AmiryNo ratings yet

- 6.11 Bullying ReadyDocument41 pages6.11 Bullying ReadyAstraX EducationNo ratings yet

- BA Euroflyer Direct Entry Pilot - Captain A320 at British AirwaysDocument1 pageBA Euroflyer Direct Entry Pilot - Captain A320 at British AirwaysdifjdjdjNo ratings yet

- Nur3116 Social Determinants of Health PaperDocument6 pagesNur3116 Social Determinants of Health Paperapi-578141969No ratings yet

- Title: Re-Gala: Rationale:: Emiliano Gala Elementary SchoolDocument2 pagesTitle: Re-Gala: Rationale:: Emiliano Gala Elementary SchoolReign Magadia BautistaNo ratings yet

- Beliefs About Obsessional Thoughts InventoryDocument21 pagesBeliefs About Obsessional Thoughts InventoryMarta CerdáNo ratings yet

- Identifying topic and supporting sentencesDocument3 pagesIdentifying topic and supporting sentencesRizkiNo ratings yet

- ReportingDocument4 pagesReportingMark CalimlimNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet Material Safety Data SheetDocument3 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet Material Safety Data SheetKarthik0% (2)

- Subject: Submission of Deficient Information / Documents: F.No.10-10/2020-OTC) (M-82)Document107 pagesSubject: Submission of Deficient Information / Documents: F.No.10-10/2020-OTC) (M-82)Saad PathanNo ratings yet

- Sex Education Literacy Stem 11 A.Document54 pagesSex Education Literacy Stem 11 A.Bangtan SeonyeondanNo ratings yet

- Confounding Variables: Ali Yassin and Bara'a Jardali Presented To Dr. Issam I. ShaaraniDocument12 pagesConfounding Variables: Ali Yassin and Bara'a Jardali Presented To Dr. Issam I. ShaaraniAli GhanemNo ratings yet

- Hts Policy PhilippinesDocument15 pagesHts Policy PhilippinesBrunxAlabastro100% (1)

- Writing Sample 2Document9 pagesWriting Sample 2api-582848179No ratings yet

- Orthop J Sports Med 2021 9 7 23259671211013394Document6 pagesOrthop J Sports Med 2021 9 7 23259671211013394Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- School Organizational ChartDocument4 pagesSchool Organizational ChartislahNo ratings yet

- CIL Recruitment for 66 Medical Executive PostsDocument12 pagesCIL Recruitment for 66 Medical Executive PostsTaseemNo ratings yet

- Improving Project ProposalsDocument2 pagesImproving Project ProposalsNancy Nicasio SanchezNo ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship vs. Global CitizenshipDocument20 pagesDigital Citizenship vs. Global CitizenshipMacasinag Jamie Anne M.No ratings yet

- Sodium Bicarbonate: PresentationDocument3 pagesSodium Bicarbonate: Presentationmadimadi11No ratings yet

- 27 Annual ReportDocument102 pages27 Annual Reportudiptya_papai2007No ratings yet

- PRA Tool Box: 6.1. Brief Introduction To PRADocument16 pagesPRA Tool Box: 6.1. Brief Introduction To PRAfaisalNo ratings yet

- Validate Questionnaire on Physical ActivitiesDocument2 pagesValidate Questionnaire on Physical ActivitiesSamantha AceraNo ratings yet

- DD - DA Li Ion MSDS U80277 2R2 - SDS 2018Document5 pagesDD - DA Li Ion MSDS U80277 2R2 - SDS 2018lintangscribdNo ratings yet

- A Concept-Based Approach To Learning: DevelopmentDocument62 pagesA Concept-Based Approach To Learning: DevelopmentAli Nawaz AyubiNo ratings yet