Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Work Stress Questionnaire WSQ - Reliability An

Uploaded by

Erica HugOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Work Stress Questionnaire WSQ - Reliability An

Uploaded by

Erica HugCopyright:

Available Formats

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7940-5

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

The Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ) –

reliability and face validity among male

workers

Anna Frantz1,2* and Kristina Holmgren2

Abstract

Background: The Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ) was developed as a self-administered questionnaire with the

purpose of early identification of individuals at risk of being sick-listed due to work-related stress. It has previously

been tested for reliability and face validity among women with satisfying results. The aim of the study was to test

reliability and face validity of the Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ) among male workers.

Method: For testing reliability, a test-retest study was performed where 41 male workers filled out the

questionnaire on two occasions at 2 weeks intervals. For evaluating face validity, seven male workers filled out the

questionnaire and gave their opinions on the questions, scale steps and how the items corresponded to their

perception of stress at work.

Results: The WSQ was, for all but one item, found to be stable over time. The item Supervisor considers one’s views

showed a systematic disagreement, i.e. there was a change common to the group for this item. Face validity was

confirmed by the male pilot group.

Conclusion: Reliability and face validity of the WSQ was found to be satisfying when used on a male population.

This indicates that the questionnaire can be used also for a male target group.

Keywords: Questionnaire, Work related stress, Men, Reliability, Face validity, Test retest

Background million USD to 187 billion [3]. The cost for sick-listing

Work-related disorders are a common problem in in Sweden 2018, taking only into account the cost for

Sweden as well as in Europe [1, 2]. A survey on work- rehabilitation benefits and sickness compensation, was

related disorders that was carried out among workers in approximately 4 billion USD, where stress-related and

Sweden in 2016, found that 26% of the female workforce adjustment disorders represented 20% of all the sick-

and 19% of the male experienced disorders related to listing cases [4]. Between the years 2012 and 2016, stress

their working situation [1]. The survey also found that as a cause of work-related disorders in Sweden increased

up until 2014, physical conditions have been the pre- from 6 to 8% for men and from 10 to 15% for women

dominant cause for work-related disorders among men, [1]. Along with staggering numbers for sick-leave, a large

however, stress and mental strain has now reached the proportion of the workforce continue to go to work des-

same levels. Estimating the cost of work-related stress to pite experiencing work-related problems [5]. Although

society is complex, depending on definition of work- there are gender differences in sick-listing, where mental

related stress and costs associated to it. The cost per disorders are a more common cause for sick-leave in

year to society has been found to range between 221.3 women [6], sick-listing due to work-related stress is

rising among both women and men [1].

* Correspondence: anna.frantz@vgregion.se It has long been known that several work-related psy-

1

Närhälsan Backa Rehabilitation Centre, Rimmaregatan 1C SE-422 55 Hisings chosocial factors such as conflicts at work, low influence

Backa, Gothenburg, Sweden

2

Department of Health and Rehabilitation, Unit of Occupational Therapy,

at work, low co-worker support, poor organizational

University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Neuroscience structure, low justice in interpersonal treatment and

and Physiology, Box 453, S-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 2 of 8

decision latitude is connected with sick leave [7–14] and work commitment as predictor of 10-year registered

common mental disorders [14, 15]. Interactive effects of sickness absence: The Population Study of Women in

poor organizational climate and high work commitment Gothenburg, in preparation].

has been found to be associated with a higher rate of

sick-leave among both women and men [16]. The world

of work is also changing. Boundaries between work and Objective

home are challenged when new technology such as Both female and male workers seem to be experiencing

smartphones leads to flexible working places and/or ill-health due to work-related stress, and this is often

hours [17, 18]. present long before sick-listing [9, 19, 20]. Stress and

Workers tend to experience ill-health due to work- mental strain as cause of work-related disorders in-

related stress long before sick-listing [9, 19, 20], and creases, not only among women but also among men

often seek help for these complaints at primary health [1]. The WSQ was developed using a female reference

care centers [21]. GPs, however, have reported not group (24). Gender differences may influence the psy-

having sufficient knowledge on how to address issues chometric properties of a questionnaire [28], it is there-

related to the patients working situation [22]. Early in- fore important to test reliability and validity of the WSQ

terventions to address stress-related disorders are of im- for men.

portance [23]. The Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ) The aim of this study was to evaluate the reliability

was developed with the intention to identify individuals and face validity of the Work Stress Questionnaire

at risk of sick-leave due to work-related stress. It has (WSQ) when used on a male working population.

been tested for reliability and face validity among

women with satisfying results [24]. In the present study,

reliability and face validity was to be tested among male Method

workers. Study design

For testing reliability, a test-retest study was performed.

The questionnaire The WSQ was filled out by the same respondent on two

The WSQ was developed by Holmgren et al. [24], as a occasions at 2 weeks intervals. Face validity was evaluated

self-administered questionnaire with the purpose of early by using a pilot-group that filled out the questionnaire

identification of individuals at risk of being sick-listed and were encouraged to give comments, either written or

due to work-related stress. It consists of only 21 ques- oral, concerning the questionnaire. The target group was

tions, which makes it suitable to use in a clinical setting non-sick-listed employed men aged 18–64 years. The

where time often is sparse. Another advantage is that it study took place in Gothenburg, Sweden 2017.

is not targeting a specific diagnosis, as other screening

tools [25, 26], but can be used to identify work-related

stress regardless of the patient’s complaint. The WSQ The work stress questionnaire (WSQ)

emanates from the experiences of sick-listed workers The WSQ consists of 21 items covering 4 main themes:

and takes into consideration the interaction between Indistinct organization and conflicts, Individual demands

personal and environmental factors [24]. It has previ- and commitment, Influence at work and Work to leisure

ously been used in a study to analyze the connection be- time interference (Additional file 1). The questions of the

tween presence of work-related stress and future work first two themes can be answered Yes, Partly or No. To

absenteeism in a primary health care setting [9] and a determine the level of stressfulness in the items of the

cohort study investigating the association between work- first two themes, the questions are followed by the ques-

related stress and ill-health/sick-leave in women [27]. In tion Do you perceive it as stressful? The respondent

the first study [9], a presence of high stress due to poor grades the level of stressfulness by answering Not stress-

organizational climate, especially when coexisting with ful, Less stressful, Stressful or Very stressful. The items of

high personal demands, significantly increased the risk the second two themes can be answered Yes, always,

of sick-leave a year later. The women in the cohort study Yes, often, No, rarely or No, never. Demographic data

experiencing a higher level of overall work-related stress concerning employment, age and educational level was

also had higher rates of self-reported ill-health [27]. also collected. In the follow-up questionnaire for the

Women reporting low influence at work and high stress- testing of reliability, a question concerning changes at

levels due to indistinct organization also had a higher the workplace during the 2-week period was added: Has

probability of sick-leave [27]. In a prospective, longitu- anything deviating occurred at your workplace since the

dinal study the WSQ was found to predict sickness ab- first time you filled out the questionnaire that may affect

sence for as far as up to 8 years [Knapstad M, Lissner L, your answers today? If the respondents answered yes to

Björkelund C, Holmgren K. Organizational climate and this question, they were excluded from the study.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 3 of 8

Procedure and data collection Table 1 Characteristics of the participants, n = 41

Respondents were recruited from different areas of the Men

labour-market using the researcher’s own social network. n = 41

Contact persons, who were not involved in any part of the % (na)

research, were used to identify and approach eligible re- Age

cruits. The procedure has similarities to snowball sam- 18–30 19.5 (8)

pling [29]. Snowball sampling uses the researchers´ social 31–40 43.9 (18)

network to reach a target group with specific characteris-

41–50 26.8 (11)

tics, in this case non-sick-listed employed men. Written

information was given to eligible recruits, containing a 51–60 4.9 (2)

short background of the study and information about the 61–64 4.9 (2)

procedure. Emphasis was laid on the voluntary nature of Educational level

participation in the study, and the respondents were in- Primary education 2.4 (1)

formed that they could choose to terminate participation Secondary education < 3 years 7.3 (3)

at any point without explanation. It was clearly stated in

Secondary education > 3 years 19.5 (8)

the written information to the participants that consent to

participate in the study was given by filling out the WSQ. University or college < 3 years 14.6 (6)

The completed questionnaire was then put in a sealed en- University or college ≥3 years 56.2 (23)

velope and passed on to the research group. This proced- Socioeconomic position

ure was then repeated 2 weeks later. The questionnaire Higher/intermediate non-manual 67.5 (27)

did not contain any personal information, only a code for Lower non-manual 22.5 (9)

matching with the second questionnaire. For this part of

Skilled manual 7.5 (3)

the study, a population of 57 employed men, aged 18–64

years, was included. Sixteen of the respondents were ex- Non-skilled manual 2.5 (1)

cluded, of which 2 respondents did not fill out the second Hours worked/week

questionnaire and 14 respondents answered yes to the Full-time 97.6 (40)

appended question Has anything deviating occurred at Part-time (> 15 h) 2.4 (1)

your workplace since the first time you filled out the ques- Employer

tionnaire that may affect your answers today? in the sec-

Private 43.9 (18)

ond questionnaire. A total of 41 respondents (n = 41)

remained for analysis. The demographics of the group are Self-employed 4.9 (2)

presented in Table 1. Public/municipal 36.6 (15)

To evaluate face validity of the WSQ, a pilot-group com- Public/regional 7.3 (3)

prising seven employed men were recruited in the same Governmental 2.4 (1)

way as for the test-retest part of the study. The group con- Other 4.9 (2)

sisted of men working in both public and private sector, at a

Dispersed numbers are due to internal drop-outs

small and large workplaces and in different positions. The

respondents were asked to fill out the WSQ and leave

notes, either written or oral, concerning the items and dichotomizing the category distributions. This made it

scales. Afterwards, the respondents were encouraged to give possible to analyze each item of the questionnaire, asses-

comments on scale steps and formulation of the questions sing the occasional and systematic disagreement of each

as well as if the questionnaire corresponded to their under- item. As some of the items are divided into two parts,

standing of work-related stress. where the first part contains the categories Yes, Partly,

No and the second part Not stressful, Less stressful,

Statistical analysis Stressful, Very stressful, these two parts were analyzed

To analyze the reliability of the questionnaire, a test- separately. Percentage agreement was calculated for both

retest analysis was performed using a rank-invariant parts, the second part was then analyzed further for

method for analysis of paired ordered categorical data Relative Rank Variance (RV), Relative Position (RP) and

described by Svensson [30]. This method for assessing Relative Concentration (RC). For all other items PA, RV,

reliability of a questionnaire has been used previously RP and RC were calculated. RV ranges from 0 to 1 and

[24, 31] and is recommended for analysis of ordered indicates individual changes. The lower the RV-number

categorical data [30]. The method is suitable for analysis is, the smaller the occasional disagreement. The items

of change and is valid regardless of the number of were also analyzed for systematic disagreement by plot-

response categories. There is no need for combining or ting each item in a graph where the x-axis represents

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 4 of 8

the cumulated proportions for the marginal distributions two of the items, Knowledge of work assignments and In-

at first test and the y-axis represents the cumulated pro- volved in conflicts at work, were not analyzed due to a

portion at retest, see Fig. 1. Each axis ranges from 0 to 1. low response rate. The respondent is only requested to

If there is no disagreement between test and retest, the answer the second part of these items if they answer the

graph will be plotted as a straight line from point (0, 0) first part with “No” and “Yes” respectively, which ex-

to point [1]. If there is a systematic disagreement, the plains why the response rate was low for these two

graph will be either concave or convex. This will be items. The first parts of these items were still analyzed

expressed as Relative Position (RP). If there has been a for PA. All but one item remained stable over time re-

systematic change in concentration, it will be expressed garding occasional and systematic disagreement, which

as the Relative Concentration (RC). If there is a change means that responses from the two measurements did

in RC it will result in an S-shaped graph. not vary regarding position on the scale or concentration

Both the RP and RC measurements were calculated of responses on group level. RV was close to 0 for all

for each item. RP and RC ranges from − 1 to 1, where a items, implying that individual variation between test

number close to 0 indicates a low disagreement between and retest was low. However, the confidence interval for

test and retest. Both RP and RC refer to changes com- RV for the item Do you take more responsibility at work

mon to the group. The confidence interval (CI) for RV, than you ought to?/stress was large (RV = 0.14, CI 0.00–

RP and RC values for each item was calculated using the 0.39). The item Supervisor considers one’s views showed

bootstrap method, based on the jack-knife standard a significant change in systematic disagreement (RP =

error. If the CI did not include 0, the item was assessed 0.10, CI 0.02–0.18), shifting towards higher response cat-

as having significantly changed between test and retest egories which means grading this item as more stressful

occasion. on retest occasion. Since the RV value was 0.0 for this

item, it cannot be explained by individual variation.

Results

Test-retest reliability Face validity

The PA of the items ranged from 55 to 98% with a me- Face validity was confirmed by the pilot-group. The par-

dian PA of 77%. To evaluate the stability of the ques- ticipants all confirmed the relevance of the questions re-

tionnaire, RV, RP and RC were calculated for each item. garding work-related stress and the items were found to

The result is presented in Table 2. The second parts of be generally easy to answer.

0.8

0.6

cum proportion y

0.4

0.2

0

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

cum proportion x

Fig. 1 The systematic disagreement of the item Does your supervisor consider your views? illustrated by a ROC curve

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 5 of 8

Table 2 Values of occasional and systematic disagreement in test-retest study

ITEM Occasional disagreement Systematic disagreement

n PA Relative rank Variance (RV) Relative Position (RP) Relative Concentration (RC)

Time to finish assignments 41 83 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) 0.05 (−0.06 to 0.15) 0.06 (− 0.02 to 0.14)

Influence decisions at work 41 78 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) 0.01 (−0.10 to 0.11) −0.02 (− 0.13 to 0.09)

Supervisor consider one’s views 41 88 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) 0.10 (0.02 to 0.18) −0.08 (− 0.17 to 0.02)

Deciding on working pace 41 73 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) −0.01 (−0.13 to 0.12) 0.09 (− 0.02 to 0.21)

Workload increased 41 85

Workload increased/Stress 22 77 0.05 (0.00 to 0.15) −0.16 (−0.33 to 0.02) 0.04 (− 0.18 to 0.26)

Clear goals at workplace 41 68

Clear goals at workplace/Stress 16 56 0.10 (0.00 to 0.27) −0.24 (−0.49 to 0.01) 0.17 (−0.07 to 0.42)

Knowledge of work assignments 41 90

Knowledge of work assignments/Stress 2a

Clear leadership 41 80

Clear leadership/Stress 11 55 0.03 (0.00 to 0.09) −0.02 (−0.31 to 0.26) 0.20 (− 0.03 to 0.43)

Conflicts at work 41 98

Conflicts at work/Stress 27 67 0.06 (0.00 to 0.18) −0.13 (−0.30 to 0.03) 0.01 (− 0.20 to 0.22)

Involved in conflicts 29 86

Involved in conflicts/Stress 6a

Supervisor solved the conflicts 29 69

Supervisor solved the conflicts /Stress 14 64 0.03 (0.00 to 0.09) −0.19 (−0.43 to 0.05) 0.05 (−0.40 to 0.50)

High demands 41 90

High demands /Stress 35 63 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) 0.02 (−0.12 to 0.17) 0.17 (−0.01 to 0.35)

Engaged 41 98

Engaged/Stress 38 71 0.06 (0.00 to 0.17) −0.01 (−0.16 to 0.13) 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.14)

Think about work 41 83

Think about work/Stress 39 69 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) 0.02 (−0.11 to 0.15) 0.08 (− 0.06 to 0.23)

Hard to set limits 41 63

Hard to set limits/Stress 30 67 0.12 (0.00 to 0.31) −0.06 (−0.24 to 0.12) 0.01 (−0.14 to 0.15)

High responsibility 41 88

High responsibility/Stress 19 68 0.14 (0.00 to 0.39) −0.07 (−0.30 to 0.16) 0.11 (−0.13 to 0.34)

Work overtime 41 63

Work overtime/Stress 26 65 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) 0.14 (−0.04 to 0.31) − 0.04 (− 0.20 to 0.12)

Sleep disturbance 41 83

Sleep disturbance/Stress 16 88 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) 0.00 (−0.16 to 0.16) 0.00 (−0.06 to 0.06)

Work interfering with family time 41 83 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) −0.06 (−0.14 to 0.01) 0.06 (− 0.05 to 0.16)

Work interfering with time to see friends 41 68 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.11) −0.02 (− 0.17 to 0.13)

Work interfering with leisure time activities 41 80 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.06) − 0.03 (− 0.15 to 0.10)

Possible RV ranges from 0 to 1 and possible RP and RC ranges from −1 to 1. The 95% confidence interval is in brackets. Significant values of the confidence

interval of RV, RP and RC are indicated in bold type

a

Items are not calculated for RV, RP and RC due to low response rate

Discussion respondents probably would have forgotten their re-

For assessing reliability of the questionnaire, a test-retest sponses from the first questionnaire but not too long so

design was chosen. This design has been suggested as that changes in work environment might have occurred

suitable for testing reliability in an already existing ques- [32]. However, ensuring the two occasions to be exactly

tionnaire [28]. The time between test and retest occasion the same is not possible. To further decrease the possibil-

was set to 2 weeks. This interval was chosen so that the ity of this affecting the answers, the appended question

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 6 of 8

Has anything deviating occurred at your workplace since either experiencing the item as stressful or not. Since

the first time you filled out the questionnaire that may the items remained stable over time, the even number of

affect your answers today? was formulated. This made it scale-steps does not seem to affect the reliability of the

possible to identify respondents who felt that there had questionnaire.

been a change in their working conditions and exclude The purpose of this study was not to screen for work-

them from analysis. related stress but to test the stability of the questionnaire

For statistical analysis a rank-invariant non-parametric over time. Snowball sampling allowed for recruitment of

method was used, which is suitable for analyzing ordinal respondents from the target group.

data. Pairing of data in this method makes it possible to There are some limitations to the study. In one part of

identify both random individual changes and systematic the questionnaire the items are divided into two, where

changes common to the group [30]. Compared to for ex- the second part is only answered if the respondent an-

ample weighted Kappa, which is a method commonly swers positively in the first part of the item. For two of the

used for analyzing changes in data, the rank invariant items, this has resulted in a low response rate to the sec-

method is not dependent on the number of categories ond part of these items. To increase probability of having

[33]. Kappa statistics also treat data as nominal. A study enough answers to be able to do a statistical analysis of

comparing the rank-invariant method used in this study these items, a larger population sample would have been

and Kappa statistics found the rank-invariant method to needed. A larger study population would also have in-

be more sensitive detecting changes in data [34]. creased the power of the statistical analysis for all items.

All but one item showed stability over time. For the item Another limitation to the study is that face validity

Supervisor considers one’s views there was a change com- was only confirmed by the pilot group. Face validity may

mon to the group, grading this item as more stressful on be the weakest form of validation, but has been sug-

retest occasion. The change was however small, with a gested as a first step in the process of validating a ques-

RP-value of 0.10 (CI 0.02–0.18). How much influence one tionnaire [28]. More thorough research to confirm the

experiences at work might be something the respondents validity of the questionnaire when used on a male popu-

have not been reflecting on, and may have been made lation is however needed.

aware of at base-line. At retest they may therefore grade

this item with higher response categories. This item was Conclusion

however not commented by the pilot group. An increasing level of men on sick leave due to stress-

The questionnaire was developed using a female refer- related disorders calls for a valid instrument for early

ence group. Gender has been identified as a factor affect- identification of persons at risk of being put out of work

ing validity of a questionnaire [28], and therefore needs due to these factors. Results from the present study indi-

to be evaluated for the target group. A report from the cate that the WSQ is a reliable and valid questionnaire

Swedish agency for work environment found that when when used on a male target group. Future research on

women and men are exposed to the same stressors at the development of the questionnaire should focus on

work they respond in a similar way [35]. In a recently more extensive evaluation of validity. The predictive

published review and meta-analysis, no gender differ- value of the questionnaire on sickness absence in a male

ences were found regarding depressive symptoms when population was not in the scope of this article and is also

exposed to the same psychosocial work factors related to an issue that needs further research.

stress [36]. This supports the findings of this study, that

the questionnaire is useful also for a male population. The

Additional file

intent of the questionnaire is to be self-administered and

therefore needs to be able to complete without reluctance Additional file 1. The Work Stress Questionnaire.

or hesitation. Few signs of this, for example written com-

ments in the questionnaire or ticking in between scale-

Abbreviations

pace boxes [37], were found in the test-retest part of the CI: Confidence interval; PA: Percentage agreement; RC: Relative

study implying that the attitudes among the participants concentration; RP: Relative position; RV: Relative rank variance; WSQ: Work

towards the questionnaire was good. Stress Questionnaire

In the WSQ, four scale-steps are available for deter-

Acknowledgements

mining the level of stressfulness of the items. How many The authors would like to thank Robin Fornazar for invaluable help during

scale-steps that should be used in questionnaires is an recruitment of respondents and processing of data.

issue that is up for debate, where there are both advan-

tages and disadvantages concerning using an even or Authors’ contributions

AF and KH designed the study. AF collected and analyzed the data and

odd number of scale-steps [37]. Using a scale with four wrote the draft manuscript. KH contributed to the data analysis and to the

steps forces the respondent to commit him- or herself to written manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 7 of 8

Funding 13. Voss M, Floderus B, Diderichsen F. Physical, psychosocial, and organisational

This study was supported by grants from the local Research Unit (FoU factors relative to sickness absence: a study based on Sweden post. Occup

Göteborg Södra Bohuslän). The funding body had no part in the study Environ Med. 2001;58(3):178–84.

design, collection, interpretation and analysis of the data, or in writing the 14. Kivimaki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Ferrie JE. Organisational justice and

manuscript. health of employees: prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2003;

60(1):27–34.

Availability of data and materials 15. Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health - a

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):443–62.

the corresponding author on reasonable request. 16. Holmgren K, Hensing G, Dellve L. The association between poor

organizational climate and high work commitments, and sickness absence

in a general population of women and men. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;

Ethics approval and consent to participate

52(12):1179–85.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Gothenburg,

17. Eurofound and the International Labour Office. Working anytime, anywhere:

Sweden, ref. nr 473–15.

the effects on the world of work. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the

Written information was given to eligible recruits, containing a short

European Union; 2017.

background of the study and information about the procedure. Emphasis

18. Mellner C. After-hours availability expectations, work-related smartphone

was laid on the voluntary nature of participation in the study, and the

use during leisure, and psychological detachment. Int J Workplace Health

respondents were informed that they could choose to terminate

Manag. 2016;9(2):146–64.

participation at any point without explanation. Consent to participate for test

19. Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Work characteristics predict

of reliability was given by filling out the questionnaire and for test of face

psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II study. Occup

validity by signing written informed consent.

Environ Med. 1999;56(5):302–7.

20. Niedhammer I, Chastang JF, David S, Barouhiel L, Barrandon G. Psychosocial

Consent for publication work environment and mental health: job-strain and effort-reward

Not applicable. imbalance models in a context of major organizational changes. Int J

Occup Environ Health. 2006;12(2):111–9.

Competing interests 21. Toft T, Fink P, Oernboel E, Christensen K, Frostholm L, Olesen F. Mental

The authors declare that they have no competing interests disorders in primary care: prevalence and co-morbidity among disorders.

Results from the functional illness in primary care (FIP) study. Psychol Med.

Received: 7 May 2019 Accepted: 12 November 2019 2005;35(8):1175–84.

22. Nilsing E, Söderberg E, Berterö C, Öberg B. Primary Healthcare Professionals’

Experiences of the Sick Leave Process: A Focus Group Study. J Occup

References Rehabil. 2013;23(3):450-61.

1. Arbetsmiljöverket (Swedish Work Environment Authority). Work-Related 23. Virtanen M, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Honkonen T, Elovainio M, Kivimäki M. Job

Disorders 2016. Stockholm: Arbetsmiljöverket; 2016. Arbetsmiljöstatistik; strain and Psychologic distress: influence on sickness absence among

rapport 2016–3 Finnish employees. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(3):182–7.

2. Eurofound. Developments in working life in Europe 2015. EurWORK annual 24. Holmgren K, Hensing G, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Development of a questionnaire

review. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2016. assessing work-related stress in women - identifying individuals who risk

3. Hassard J, Teoh KRH, Visockaite G, Dewe P, Cox T. The cost of work-related being put on sick leave. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(4):284–92.

stress to society: a systematic review. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23(1):1–17. 25. Shaw W, van der Windt D, Main C, Loisel P, Linton S. Early patient screening

4. Regeringens skrivelse 2018/19:101 Årsredovisning för staten 2018. 2019. (The and intervention to address individual-level occupational factors (“blue

Governments writ/document 2018/19:101; Annual report of the state 2018. 2019). flags”) in Back disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(1):64–80.

5. Janssens H, Clays E, De Clercq B, De Bacquer D, Casini A, Kittel F, et al. 26. Lexis M, Jansen N, Amelsvoort L, Huibers M, Berkouwer A, Tjin A, Ton G,

Association between psychosocial characteristics of work and presenteeism: et al. Prediction of long-term sickness absence among employees with

a cross-sectional study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2016;29(2):331–44. depressive complaints. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(2):262–9.

6. Ferrie JE, Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Westerlund H, Melchior M, Alexanderson K, 27. Holmgren K, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Björkelund C, Hensing G. The prevalence of

et al. Diagnosis-specific sickness absence and all-cause mortality in the work-related stress, and its association with self-perceived health and sick-

GAZEL study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:50–5. leave, in a population of employed Swedish women. BMC Public Health.

7. Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Pentti J, Theorell T. Effect of change in the 2009;9(73). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-73.

psychosocial work environment on sickness absence: a seven year follow 28. Switzer GE, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Dew MA, Schultz R. Selecting,

up of initially healthy employees. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000; developing, and evaluating research instruments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr

54(7):484–93. Epidemiol. 1999;34(8):399–409.

8. Falco A, Girardi D, Marcuzzo G, De Carlo A, Bartolucci GB. Work stress and 29. Morgan DL. Snowball sampling. In: Given LM, editor. The SAGE Encyclopedia of

negative affectivity: a multi-method study. Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63(5): Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE publication; 2008. p. 816–7.

341–7. 30. Svensson E. Ordinal invariant measures for individual and group changes in

9. Holmgren K, Fjallstrom-Lundgren M, Hensing G. Early identification of work- ordered categorical data. Stat Med. 1998;17(24):2923–36.

related stress predicted sickness absence in employed women with 31. Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Sonn U, Svensson E. Development of an ADL instrument

musculoskeletal or mental disorders: a prospective, longitudinal study in a targeting elderly persons with age-related macular degeneration. Disabil

primary health care setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(5):418–26. Rehabil. 2001;23(2):69–79.

10. Vaananen A, Kalimo R, Toppinen-Tanner S, Mutanen P, Peiro JM, Kivimaki M, 32. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-

et al. Role clarity, fairness, and organizational climate as predictors of Hill; 1994.

sickness absence: a prospective study in the private sector. Scand J Public 33. Brenner H, Kliebsch U. Dependence of weighted kappa coefficients on the

Health. 2004;32(6):426–34. number of categories. Epidemiology. 1996;7(2):199–202.

11. Head J, Kivimaki M, Siegrist J, Ferrie JE, Vahtera J, Shipley MJ, et al. Effort- 34. Bunketorp L, Carlsson J, Kowalski J, Stener-Victorin E. Evaluating the

reward imbalance and relational injustice at work predict sickness absence: reliability of multi-item scales: a non-parametric approach to the ordered

the Whitehall II study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(4):433–40. categorical structure of data collected with the swedish version of the

12. Andrea H, Beurskens AJ, Metsemakers JF, van Amelsvoort LG, van den Tampa scale for kinesiophobia and the self-efficacy scale. J Rehabil Med.

Brandt PA, van Schayck CP. Health problems and psychosocial work 2005;37:330–4.

environment as predictors of long term sickness absence in employees 35. Sverke M, Falkenberg H, Kecklund G, Magnusson Hanson L, Lindfors P.

who visited the occupational physician and/or general practitioner in Kvinnors och mäns arbetsvillkor - betydelsen av organisatoriska faktorer och

relation to work: a prospective study. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(4): psykosocial arbetsmiljö för arbets- och hälsorelaterade utfall. Stockholm:

295–300. Arbetsmiljöverket (Swedish Work Environment Authority); 2016.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Frantz and Holmgren BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1580 Page 8 of 8

36. Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, Träskman Bendz L, Grape T,

Hogstedt C, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work

environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2015;15. https://

doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4.

37. Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical

guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Incorporated: Oxford

University Press; 2015.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- BKT NotesDocument6 pagesBKT NotesPallavi ChopraNo ratings yet

- Psychometrics of Arabic Version of The UWES-9Document6 pagesPsychometrics of Arabic Version of The UWES-9International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management100% (1)

- Parenting and SEconomicsocialDocument6 pagesParenting and SEconomicsocialNeiler OverpowerNo ratings yet

- Measures of AnxietyDocument6 pagesMeasures of AnxietySusana DíazNo ratings yet

- Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents With Epilepsy. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and TreatmentDocument11 pagesDepression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents With Epilepsy. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and TreatmentGabriel Guillén RuizNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction Anxiety ScaleDocument2 pagesSocial Interaction Anxiety ScaleReneah Krisha May MedianoNo ratings yet

- The Temporal Satisfaction With Life ScaleDocument3 pagesThe Temporal Satisfaction With Life ScaleLaura QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Eysenck Personality To CommunicateDocument48 pagesEysenck Personality To CommunicateYenni RoeshintaNo ratings yet

- Assess social support with the SSQSRDocument3 pagesAssess social support with the SSQSRRaafi Puristya Aries DarmawanNo ratings yet

- History and application of culture fair intelligence testsDocument3 pagesHistory and application of culture fair intelligence testsYesha HermosoNo ratings yet

- PRACTICAL RECORD - Percieved Stress ScaleDocument2 pagesPRACTICAL RECORD - Percieved Stress ScaleMalavika BNo ratings yet

- The Guidance PersonnelDocument27 pagesThe Guidance PersonnelLeonard Patrick Faunillan BaynoNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Assessment of Infants, Preschoolers and Their Families - IACAPAPDocument22 pagesThe Clinical Assessment of Infants, Preschoolers and Their Families - IACAPAPcpardilhãoNo ratings yet

- Ali Raza Report Till Formal Ass NewDocument11 pagesAli Raza Report Till Formal Ass NewAtta Ullah ShahNo ratings yet

- School-Based Prevention of Anxiety and Depression: A Pilot Study in SwedenDocument13 pagesSchool-Based Prevention of Anxiety and Depression: A Pilot Study in SwedenSandra QueroNo ratings yet

- A Global Measure of Perceived StressDocument13 pagesA Global Measure of Perceived Stressleonfran100% (1)

- Oppositional Defiant Disorders Case Study FinalDocument7 pagesOppositional Defiant Disorders Case Study Finalmotivated165No ratings yet

- Coping Strategy of Male and Female Grocery Workers - LADocument36 pagesCoping Strategy of Male and Female Grocery Workers - LALawrence Albert MacaraigNo ratings yet

- Psychological Well BeingDocument78 pagesPsychological Well BeingNeile Aidylene RecintoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument32 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundPRINCESS JOY BUSTILLONo ratings yet

- Holm & Holroyd The Daily Hassles Scale Revised 1992 PDFDocument18 pagesHolm & Holroyd The Daily Hassles Scale Revised 1992 PDFRot MariusNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Aspects of The W-DeQ WijmaDocument14 pagesPsychometric Aspects of The W-DeQ WijmaAnonymous Rq75cuX7100% (1)

- Concern Over Weight and Dieting Scale (COWD)Document135 pagesConcern Over Weight and Dieting Scale (COWD)MilosNo ratings yet

- Dimensions ReligionDocument7 pagesDimensions ReligionArif GunawanNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Personality and Academic PerformanceDocument5 pagesRelationship Between Personality and Academic Performancereferatelee1No ratings yet

- 16PF BibDocument10 pages16PF BibdocagunsNo ratings yet

- Assignment On BDIDocument15 pagesAssignment On BDIsushila napitNo ratings yet

- Emotion Regulation (2019)Document12 pagesEmotion Regulation (2019)Zahra ZalafieNo ratings yet

- Coping With Anxiety in Sport: Yuri L. HaninDocument17 pagesCoping With Anxiety in Sport: Yuri L. HaninmonalisaNo ratings yet

- 30-Item Coping Style QuestionnaireDocument2 pages30-Item Coping Style QuestionnaireVasilica100% (1)

- Vangeelen2015 PDFDocument8 pagesVangeelen2015 PDFHafizah Khairi DafnazNo ratings yet

- Resilience and PersonalityDocument14 pagesResilience and PersonalityogimaminNo ratings yet

- Analysis Report: My Choice My Future (MCMF)Document20 pagesAnalysis Report: My Choice My Future (MCMF)Crazerzz LohithNo ratings yet

- Down's Syndrome Pada KehamilanDocument35 pagesDown's Syndrome Pada KehamilanArga AdityaNo ratings yet

- CGASDocument4 pagesCGASDinny Atin AmanahNo ratings yet

- Demographic and psychological assessment reportDocument3 pagesDemographic and psychological assessment reportmobeenNo ratings yet

- Stress WorkersDocument10 pagesStress WorkersAdriana Cristiana PieleanuNo ratings yet

- Locke-Wallace Short Marital-Adjustment TestDocument16 pagesLocke-Wallace Short Marital-Adjustment TestelvinegunawanNo ratings yet

- A Comparative study of Job satisfaction i.e. job intrinsic (job concrete such as excursions, place of posting, working conditions; Job-abstract such as cooperation, democratic functioning) and Job-Extrinsic like psycho-social such as intelligence, social circle; economic such salary, allowance; community/National growth such as quality of life, national economy and Multidimensional coping like task oriented, emotion-oriented, avoidance oriented like distraction and social diversion of employees in Mizoram University.Document7 pagesA Comparative study of Job satisfaction i.e. job intrinsic (job concrete such as excursions, place of posting, working conditions; Job-abstract such as cooperation, democratic functioning) and Job-Extrinsic like psycho-social such as intelligence, social circle; economic such salary, allowance; community/National growth such as quality of life, national economy and Multidimensional coping like task oriented, emotion-oriented, avoidance oriented like distraction and social diversion of employees in Mizoram University.International Journal of Business Marketing and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Percieved Stress Scale PDFDocument2 pagesPercieved Stress Scale PDFclaraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Subjective Happiness and Wisdom of Retired ProfessionalsDocument6 pagesRelationship Between Subjective Happiness and Wisdom of Retired ProfessionalsTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Career Decision Making and Socioeconomic StatusDocument10 pagesCareer Decision Making and Socioeconomic StatusWawan Ramona LavigneNo ratings yet

- K-GSADS-A - Package Posible Prueba para Medir SOCIAL PHOBIADocument16 pagesK-GSADS-A - Package Posible Prueba para Medir SOCIAL PHOBIABetsyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Homesickness Amoung Undergraduate StudentsDocument63 pagesPrevalence of Homesickness Amoung Undergraduate Students17 Irine Mary MathewNo ratings yet

- Understanding Stress, Trauma, and Their Effects on the Body and MindDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Stress, Trauma, and Their Effects on the Body and MindprabhuthalaNo ratings yet

- STAXI Kaashvi DubeyDocument18 pagesSTAXI Kaashvi Dubeykaashvi dubeyNo ratings yet

- Answer-Sheet OF Standard Progressive Matrices Sets A, B. C, D, & EDocument2 pagesAnswer-Sheet OF Standard Progressive Matrices Sets A, B. C, D, & Egod_26No ratings yet

- NOTES Groups HepworthDocument4 pagesNOTES Groups Hepworthejanis39No ratings yet

- I Think I Can, I Think I Can - Brand Use, Self-Efficacy, and PerformanceDocument16 pagesI Think I Can, I Think I Can - Brand Use, Self-Efficacy, and PerformanceRandy HoweNo ratings yet

- Compulsory Critique NEO PI RDocument16 pagesCompulsory Critique NEO PI RElizabeth Forsyth80% (5)

- Robertson Emotional Distress ScaleDocument1 pageRobertson Emotional Distress Scalenimra rafiNo ratings yet

- WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire Measures Quality of LifeDocument12 pagesWHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire Measures Quality of LifeNYONGKERNo ratings yet

- Assessing Family Relationships with FACES IVDocument7 pagesAssessing Family Relationships with FACES IVSarai100% (1)

- Personality TestDocument15 pagesPersonality TestMitesh KumarNo ratings yet

- A Critical Survey of Coping InstrumentsDocument28 pagesA Critical Survey of Coping InstrumentsHendric0% (1)

- Davids Good Copy ReportDocument10 pagesDavids Good Copy Reportapi-290018716No ratings yet

- Does Unemployment Contribute To Poorer Health-Related Quality of Life Among Swedish Adults?Document12 pagesDoes Unemployment Contribute To Poorer Health-Related Quality of Life Among Swedish Adults?BobanBisercicNo ratings yet

- Art 7Document12 pagesArt 7Zulma TenaNo ratings yet

- 1 HHVHVHKVMDocument9 pages1 HHVHVHKVMCreative Brain Institute of PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Dying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance—and What We Can Do About ItFrom EverandDying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance—and What We Can Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- NURS 366 Exam 1 Study Guide and RubricDocument7 pagesNURS 366 Exam 1 Study Guide and RubriccmpNo ratings yet

- Museum functional areas guideDocument8 pagesMuseum functional areas guideChelle CruzNo ratings yet

- VASHISTA AND S1 DEVELOPMENT ONSHORE TERMINALDocument8 pagesVASHISTA AND S1 DEVELOPMENT ONSHORE TERMINALKrm ChariNo ratings yet

- MP Maxat Pernebayev Tanvi Singh Karthick SundararajanDocument117 pagesMP Maxat Pernebayev Tanvi Singh Karthick SundararajansadiaNo ratings yet

- SOP of Gram StainDocument5 pagesSOP of Gram Stainzalam55100% (1)

- Grundfosliterature 743129Document7 pagesGrundfosliterature 743129Ted Andrew AbalosNo ratings yet

- Heavy Oil's Production ProblemsDocument22 pagesHeavy Oil's Production Problemsalfredo moran100% (1)

- Points - Discover More RewardsDocument1 pagePoints - Discover More RewardsMustapha El HajjNo ratings yet

- Dead ZoneDocument10 pagesDead ZoneariannaNo ratings yet

- EVBAT00100 Batterij ModuleDocument1 pageEVBAT00100 Batterij ModuleSaptCahbaguzNo ratings yet

- Thermal Destruction of Microorganisms in 38 CharactersDocument6 pagesThermal Destruction of Microorganisms in 38 CharactersRobin TanNo ratings yet

- Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak YojanaDocument19 pagesPradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojanapriyajaiswal428No ratings yet

- Antibiotic Susceptibility TestDocument5 pagesAntibiotic Susceptibility Testfarhanna8100% (3)

- Standardized Recipes - Doc2Document130 pagesStandardized Recipes - Doc2epic failNo ratings yet

- Medical Certificate: (Coaches, Assistant Coaches, Chaperone)Document1 pageMedical Certificate: (Coaches, Assistant Coaches, Chaperone)Keith Marinas Serquina100% (1)

- Knime SeventechniquesdatadimreductionDocument266 pagesKnime SeventechniquesdatadimreductionramanadkNo ratings yet

- NABARD Presentation On FPODocument14 pagesNABARD Presentation On FPOSomnath DasGupta71% (7)

- Bonding BB1Document3 pagesBonding BB1DeveshNo ratings yet

- 9-10 Manajemen Fasilitas Dan Keselamatan - PCC, HSEDocument30 pages9-10 Manajemen Fasilitas Dan Keselamatan - PCC, HSEMars Esa UnggulNo ratings yet

- F 856 - 97 - Rjg1ni05nw - PDFDocument7 pagesF 856 - 97 - Rjg1ni05nw - PDFRománBarciaVazquezNo ratings yet

- SCR10-20PM Compressor ManualDocument36 pagesSCR10-20PM Compressor ManualTrinnatee Chotimongkol100% (2)

- Audi A6 Allroad Model 2013 Brochure - 2012.08Document58 pagesAudi A6 Allroad Model 2013 Brochure - 2012.08Arkadiusz KNo ratings yet

- Five Brothers and Their Mother's LoveDocument4 pagesFive Brothers and Their Mother's Lovevelo67% (3)

- TYF Oxit: Ready-to-Use, High-Performance Ultra Low Viscous Secondary Refrigerants For Applications Down To - 50 °CDocument9 pagesTYF Oxit: Ready-to-Use, High-Performance Ultra Low Viscous Secondary Refrigerants For Applications Down To - 50 °Cmarcyel Oliveira WoliveiraNo ratings yet

- Working at Height PolicyDocument7 pagesWorking at Height PolicyAniekan AkpaidiokNo ratings yet

- Transformer Protection Techniques for Fault DetectionDocument32 pagesTransformer Protection Techniques for Fault DetectionshashankaumNo ratings yet

- On of Smart Crab Water Monitoring System Using ArduinoDocument46 pagesOn of Smart Crab Water Monitoring System Using ArduinoLayla GarciaNo ratings yet

- Indian School Sohar Term II Examination 2018-19 EnglishDocument4 pagesIndian School Sohar Term II Examination 2018-19 EnglishRitaNo ratings yet

- 08 Ergonomics - 01Document35 pages08 Ergonomics - 01Cholan PillaiNo ratings yet

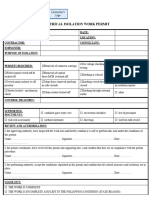

- Electrical Isolation Work PermitDocument2 pagesElectrical Isolation Work PermitGreg GenoveNo ratings yet