Professional Documents

Culture Documents

En - 0100 6991 RCBC 46 01 E2059

Uploaded by

Deddy WidjajaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

En - 0100 6991 RCBC 46 01 E2059

Uploaded by

Deddy WidjajaCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI: 10.

1590/0100-6991e-20192059 Original Article

Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit.

Fraturas de esterno em uma unidade de tratamento intensivo especializada

em trauma.

Leonardo Dantas da Silva Pereira1; Estevão Bassi1; Bruno Martins Tomazini1; Vinicius Luiz Menezes Jesus1; Paulo Fernando Guimarães

Morando Marzocchi Tierno1; Fernando Da Costa Ferreira Novo1; Luiz Marcelo Malbouisson2; Edivaldo Massazo Utiyama, TCBC-SP1

A B S T R A C T

Objective: to evaluate epidemiology, anatomical characteristics, management, and prognosis of critical patients with

sternum fractures. Methods: retrospective analysis of patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) of a Level III trauma

center in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Results: 1552 trauma patients were admitted from January 2012 to April 2016. A total of

439 patients had thoracic trauma and among these, 13 patients had sternum fracture, making up 0.9% of all trauma

admissions and 3% of all thoracic trauma cases. Three of these 13 patients had unstable chest, two underwent surgical

management for fracture fixation, and three died (mortality was of 29%). In one of the deaths, sternum fracture was

assessed as the main contributor to the outcome. Conclusion: sternum fracture was diagnosed in 0.9% of critical trauma

patients in a specialized ICU. Only 15% of patients required specific surgical management in the acute phase. In most

cases, mortality was due to other injuries.

Keywords: Thoracic Injuries. Critical Care. Flail Chest. Intensive Care Units.

INTRODUCTION The most common associated lesions in these patients

are costal arch fractures, traumatic brain injury (TBI),

R

ibcage lesions are a common type of injury in spinal injuries, and pulmonary contusions4. Data from

trauma patients1 and their presence is related the United States show that mortality rate is low (2.4%)

to morbimortality increase, with rates reaching 60% in patients with isolated sternal fracture. However,

in this population2. Motor vehicle accident is the this rate can increase up to 8.8% in the presence

most common trauma mechanism and closed chest of other associated lesions7. In this population, the

trauma is the predominant type of injury1. Within independent risk factors associated with mortality

this subgroup of patients, sternum fractures were are thoracic lesion, pulmonary contusions, acute

considered uncommon, with incidence ranging respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), age, and days of

from 0.3% to 3.7%3. However, this incidence has mechanical ventilation.

been increasing in recent decades, fact which may Literature describes a topographic division

be related to the increased use of seat belts4. of the sternum in four distinct anatomical regions,

In this context, computed tomography a specific subdivision for manubrium fractures4,8,9

(CT) has increased diagnostic accuracy, since up to (types A, B, and C fractures, depending on the

94% of all sternum fractures are not diagnosed in generated instability - sagittal, rotational, or

initial chest X-ray examination5. The use of whole- combined, respectively), and the sternal body,

body CT protocols allows the accurate diagnosis divided into these portions: upper (Part I), mid

of associated lesions and other complications6. (Part II), and distal, including xiphoid process (Part III).

1 - University of Sao Paulo (USP), Faculty of Medicine, Department of Surgery Division of General Surgery and Trauma, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2 - University of Sao Paulo (USP), Faculty of Medicine, Department of Anaesthesiology, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

Pereira

2 Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit.

This division becomes relevant because fractures in This work was approved by the Institutional

certain areas of the sternum are more related to Ethics Committee with the following reference

specific associated lesions4. Remarkably, manubrium number 63077116.6.0000.0068.

fractures are associated with thoracic spine,

RESULTS

scapular, and TBI lesions, while Part III fractures are

more related to lumbar spine fractures. During this study period, 2667 patients

Most sternum fractures are stable were admitted to our ICU, 1522 of which were

and without obvious misalignments, and have trauma victims. A total of 439 patients had thoracic

conservative management10. Surgical options may be trauma (ribcage lesions) and among these, 13

considered in patients with unstable sternal fractures, patients had sternum fracture, making up 0.9% of

unsatisfactory pain control despite optimized clinical all trauma admissions and 3% of all thoracic trauma

treatment, or difficulty in ventilation weaning cases. Sternum fractures were more common in men

attributed to fracture. A strategy of late surgical (84.6%), with median age of 32 years. The most

approach may be useful in cases of patients with common trauma mechanisms were motor vehicle

chronic pain, no fracture consolidation, or aesthetic accidents (46%), falls from a height (38%), and

reasons11. However, in selected groups of patients, tramplings (15%). Associated with thoracic lesions,

such as those with pericardial effusion and possible 38% of patients had TBI; 38%, pelvic trauma;

vascular lesions due to sternum trauma, emergency 38%, extremity trauma; 31%, spinal trauma; and

surgical stabilization is indicated. 23%, abdominal trauma. Admission characteristics

METHODS of these patients are shown in table 1. Median

Simplified Acute Physiology Score III (SAPS III) was

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 54, median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 34, and

adult patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit (ICU) median New Injury Severity Score (NISS) was 43.

of a Level III trauma center in Sao Paulo, Brazil, from Median duration of mechanical ventilation in these

January 2012 to April 2016. This observational patients was six days, with median hospitalization

study had the objective of describing epidemiology, duration in ICU of ten days and median length of

anatomical characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospital stay of 29 days. Hospital mortality was of

with sternum fracture in this population. 23%.

Continuous variables were described as Most fractures affected the sternal

median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and manubrium (62%), followed by the body (30%) and

standard deviation, as appropriate. Categorical sternoclavicular junction (8%). Only three patients

data were expressed as percentages and absolute (23%) had unstable chest attributed to sternal

values. Due to the descriptive epidemiological fracture, and two underwent surgical fixation of the

nature of this study, no other statistical analysis fracture. Both patients had satisfactory outcomes at

was performed. hospital discharge (Table 2).

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

Pereira

Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit. 3

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

Median age (IQR) 32 (27-38) years

Men 84.6%

Median SAPS III*(IQR) 54 (35-65)

Trauma mechanism

Motor vehicle accidents 46%

Falls from a height 38%

Tramplings 15%

Associated lesions

TBI** 38%

Pelvic trauma 38%

Extremity trauma 38%

Spinal trauma 31%

Abdominal trauma 23%

Median ISS***(IQR) 34 (25-43)

Median NISS****(IQR) 43 (41-50)

Median hospitalization duration in ICU/days (IQR) 10 (5-22)

Median length of hospital stay/days (IQR) 29 (13-36)

Hospital mortality 23%

* SAPS III: Simplified Acute Physiology Score III; ** TBI: traumatic brain injury; *** ISS: Injury Severity Score; **** NISS: New

Injury Severity Score.

Table 2. Fracture location, unstable chest, and surgical fixation.

Fracture location Unstable chest Surgical fixation

Manubrium NO NO

Body NO NO

Manubrium NO NO

Sternoclavicular junction NO NO

Body NO NO

Body NO NO

Body NO NO

Body NO NO

Body YES YES

Body NO NO

Body YES NO

Manubrium NO NO

Manubrium YES YES

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

Pereira

4 Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit.

Three patients with sternal fracture died The epidemiological characteristics of our

during observation period, two due to nonrespiratory series were also in line with international literature, in

complications. One of these patients had a diagnosis which most lesions are of sternal body, with motor

of brain death on the 12th day of ICU admission vehicle accidents as the most common trauma

due to TBI. One patient died nine days after mechanism. However, a considerable portion of our

admission due to anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy patients had other high-energy trauma mechanisms

after cardiorespiratory arrest at the scene. The third as causal agent, notably fall from a height and

patient presented retrosternal hematoma caused trampling. This reinforces that such mechanisms

by sternal fracture and died on the first day of should not be underestimated as risk factors for

hospitalization due to shock and respiratory failure traumatic lesion of the sternum, especially given the

(Table 3). high prevalence of this trauma mechanism, both in

developed and developing countries12,13.

DISCUSSION

Considering that our study had as inclusion

There is a shortage of national studies on criteria only patients admitted to ICU, severity

the epidemiology of sternal fractures in critically indexes and prognostic scores such as SAPS III, ISS,

ill trauma victims. In our series, the prevalence of and NISS were higher than those found in literature.

sternum fractures was 0.9% of total trauma, in For the same reason, mortality in our population was

agreement with international literature in which higher than in other series. However, most of the

prevalence ranges from 0.3% to 3.7%3. Our data did deaths occurred in patients with other associated

not allow us to evaluate possible historical increase lesions, which had a direct contribution to the cause

trends in the incidence of these fractures. This of death. In fact, only in one patient, the cause of

increased incidence in the last decades described in death was directly attributed to sternal fracture.

foreign literature is due to both a greater diagnostic Therefore, we consider that sternum fractures are

accuracy and to the mandatory use of three-point a severity marker in patients admitted to ICU. By high-

seat belt for drivers and front passengers, which energy trauma mechanism, these fractures are most

causes a point of greater pressure in the anterior of the time associated with other severe lesions,

chest region during deceleration. such as TBI and pelvic and abdominal traumas.

Table 3. Patients with fatal lesions.

Fracture SAPS III* NISS** Cause of death Day

Manubrium + Retrosternal hematoma 50 50 Brain death (TBI***) 12

Body + Retrosternal hematoma 63 50 Shock + Respiratory failure 1

Body (fracture) 65 41 Anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy 9

(cardiorespiratory arrest at the scene)

* SAPS III: Simplified Acute Physiology Score III; ** NISS: New Injury Severity Score; *** TBI: traumatic brain injury.

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

Pereira

Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit. 5

For a very selected population of patients The low number of events does not allow any analysis

with sternal trauma, especially those with clinical of the association of risk factors or prognostic

instability of the fracture and unstable chest, predictors in our population. As far as we know,

surgical fixation, although little studied in clinical this is the first national historical series which

trials, seems to bring benefits to these patients, such evaluates the prevalence of sternal fractures in

as facilitating the withdrawal of invasive mechanical a population of trauma victims. The presence of

ventilation, the main benefit. sternal fracture and associated lesions may be

Our case series presents some limitations: it related to the outcome of these patients. For a very

is a retrospective study, without an individual analysis specific group, surgical fixation may be indicated

of the significance of whole-body tomography in our and beneficial. However, further studies on this

population, which may increase the prevalence of lesions. topic are needed.

R E S U M O

Objetivo: avaliar epidemiologia, características anatômicas, manejo e prognóstico de pacientes críticos com fraturas de

esterno. Métodos: análise retrospectiva de pacientes internados em unidade de terapia intensiva (UTI) de emergências

cirúrgicas e trauma de um centro de trauma Tipo III em São Paulo, Brasil. Resultados: foram admitidos 1552 pacientes

traumatizados no período de janeiro de 2012 a abril de 2016. Desses, 439 apresentavam trauma torácico e 13

apresentavam fratura de esterno, configurando 0,9% das admissões de trauma e 3% dos traumas torácicos. Desses

pacientes, três apresentavam tórax instável e dois foram submetidos à conduta cirúrgica para fixação da fratura. A

mortalidade de pacientes com fratura de esterno foi de 29% (três pacientes). Em um dos óbitos pôde-se atribuir a fratura

do esterno como contribuinte principal para o desfecho. Conclusão: a fratura de esterno foi diagnosticada em 0,9% dos

pacientes críticos vítimas de trauma em UTI especializada. Somente 15% dos pacientes necessitaram de conduta cirúrgica

específica na fase aguda e a mortalidade foi decorrente das outras lesões na maior parte dos casos.

Descritores: Traumatismos Torácicos. Cuidados Críticos. Parede Torácica. Unidades de Terapia Intensiva.

REFERENCES 5. Perez MR, Rodriguez RM, Baumann BM, Langdorf

MI, Anglin D, Bradley RN, et al. Sternal fracture in

1. Majercik S, Pieracci FM. Chest wall trauma. Thorac the age of pan-scan. Injury. 2015;46(7):1324-7.

Surg Clin. 2017;27(2):113-21. 6. Ahmad K, Katballe N, Pilegaard H. Fixation of sternal

2. Clark GC, Schecter WP, Trunkey DD. Variables fracture using absorbable plating system, three

affecting outcome in blunt chest trauma: flail years follow-up. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(5):E131-4.

chest vs. pulmonary contusion. J Trauma. 1988; 7. Yeh DD, Hwabejire JO, DeMoya MA, Alam HB,

28(3):298-304. King DR, Velmahos GC. Sternal fracture--an

3. Racine S, Émond M, Audette-Côté JS, Le Sage N, analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Surg

Guimont C, Moore L, et al. Delayed complications Res. 2014;186(1):39-43.

and functional outcome of isolated sternal 8. Schulz-Drost S, Krinner S, Oppel P, Grupp S,

fracture after emergency department discharge: Schulz-Drost M, Hennig FF, et al. Fractures of

a prospective, multicentre cohort study. CJEM. the manubrium sterni: treatment options and

2018;18(5):349-57. a possible classification of different types of

4. Scheyerer MJ, Zimmermann SM, Bouaicha fractures. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(3):1394-405.

S, Simmen HP, Wanner GA, Werner CM. 9. Otremski I, Wilde BR, Marsh JL, McLardy Smith

Location of sternal fractures as a possible PD, Newman RJ. Fracture of the sternum in

marker for associated injuries. Emerg Med Int. motor vehicle accidents and its association with

2013;2013:407589. mediastinal injury. Injury. 1990;21(2):81-3.

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

Pereira

6 Sternal fractures in a level III trauma intensive care unit.

10. Zhao Y, Yang Y, Gao Z, Wu W, He W, Zhao T. developing countries: report from a nationwide

Treatment of traumatic sternal fractures with cross-sectional survey of Sierra Leone. JAMA Surg.

titanium plate internal fixation: a retrospective 2013;148(5):463-9.

study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12(1):22.

11. Elkhayat H, Nousseir H. Fixing a traumatic sternal Received in: 11/09/2018

fracture using stainless steel wires. Trauma Mon. Accepted for publication: 01/02/2019

2016;21(2):e27231. Conflict of interest: none.

12. DiMaggio C, Ayoung-Chee P, Shinseki M, Wilson Source of funding: none.

C, Marshall G, Lee DC, et al. Traumatic injury in the

United States: In-patient epidemiology 2000-2011. Mailing address:

Injury. 2016;47(7):1393-1403. Estevão Bassi

13. Stewart KA, Groen RS, Kamara TB, Farahzard M, E-mail: estbassi@gmail.com

Samai M, Yambasu SE, et al. Traumatic injuries in

Rev Col Bras Cir 46(1):e2059

You might also like

- 2Document17 pages2fikryahNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Thoracic Trauma Severity Score in Predicting The Outcome of Isolated Blunt Chest Trauma PatientsDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Thoracic Trauma Severity Score in Predicting The Outcome of Isolated Blunt Chest Trauma PatientsGabriel KlemensNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Thoracic Trauma Severity Score in Predicting The Outcome of Isolated Blunt Chest Trauma PatientsDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Thoracic Trauma Severity Score in Predicting The Outcome of Isolated Blunt Chest Trauma PatientsGabriel KlemensNo ratings yet

- Trauma Toracico Bilateral. ManejoDocument4 pagesTrauma Toracico Bilateral. ManejoJuan Manuel Arboleda ZapataNo ratings yet

- Original Article Original Article Original Article Original Article Original ArticleDocument6 pagesOriginal Article Original Article Original Article Original Article Original ArticleruliNo ratings yet

- The Prognostic Significance of Thoracic and Abdominal Trauma in Severe Trauma PatientsDocument6 pagesThe Prognostic Significance of Thoracic and Abdominal Trauma in Severe Trauma PatientsYuyun Jenong18No ratings yet

- Blunt Thoracic Trauma - Role of Chest Radiography and Comparison With CT - Fndings and Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesBlunt Thoracic Trauma - Role of Chest Radiography and Comparison With CT - Fndings and Literature Revieworalposter PIPKRA2023No ratings yet

- SW Di NigeriaDocument4 pagesSW Di NigeriaqweqweqwNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Characterization of Major Upper-Extremity Amputations in The National Trauma Data BankDocument7 pagesIncidence and Characterization of Major Upper-Extremity Amputations in The National Trauma Data BankGhea Jovita SinagaNo ratings yet

- Chest Injury Due To Blunt TraumaDocument5 pagesChest Injury Due To Blunt TraumanelamNo ratings yet

- Chinese Journal of TraumatologyDocument5 pagesChinese Journal of Traumatologybulan hasanNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Blunt Chest Trauma With Multidetector Computed TomographyDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Blunt Chest Trauma With Multidetector Computed TomographyasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- BicepsarticuloDocument5 pagesBicepsarticuloRommel AndresNo ratings yet

- 2016 Challenges in Warrelated Thoracic Injury Faced by French Military Surgeons in AfghanistanDocument6 pages2016 Challenges in Warrelated Thoracic Injury Faced by French Military Surgeons in AfghanistanlepongeNo ratings yet

- FHFHFHFHFHHFHFFHFHFDocument18 pagesFHFHFHFHFHHFHFFHFHFJeffrey GillespieNo ratings yet

- Pamj 33 234Document8 pagesPamj 33 234Saffa AzharaaniNo ratings yet

- Acute Compartment Syndrome of The ForearmDocument6 pagesAcute Compartment Syndrome of The ForearmVerra Apriawanti AmriNo ratings yet

- Hospital Management of Abdominal Trauma in Tehran, Iran: A Review of 228 PatientsDocument4 pagesHospital Management of Abdominal Trauma in Tehran, Iran: A Review of 228 Patientssiska khairNo ratings yet

- Mehboob Alam Pasha, Mohd - Faris Mokhtar, Mohd - Ziyadi GhazaliDocument7 pagesMehboob Alam Pasha, Mohd - Faris Mokhtar, Mohd - Ziyadi GhazaliOTOH RAYA OMARNo ratings yet

- Clinical Outcomes of Locked Plating of Distal Femoral Fractures in A Retrospective CohortDocument9 pagesClinical Outcomes of Locked Plating of Distal Femoral Fractures in A Retrospective Cohortisnida shela arloviNo ratings yet

- Rodrigo Py Gonçalves Barreto Bilateral MagneticDocument8 pagesRodrigo Py Gonçalves Barreto Bilateral MagneticfilipecorsairNo ratings yet

- Airway TraumaDocument7 pagesAirway TraumaDanychimerNo ratings yet

- Seguridad Del PacienteDocument14 pagesSeguridad Del PacienteTamara PricilaNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Transpedicular Screw Fixation With Unstable Thoracolumber Spine InjuryDocument5 pagesOutcomes of Transpedicular Screw Fixation With Unstable Thoracolumber Spine InjuryMJSPNo ratings yet

- Fracturas de ClaviculaDocument11 pagesFracturas de ClaviculaJalil CardenasNo ratings yet

- Katsuura 2016Document6 pagesKatsuura 2016Wahyu InsanNo ratings yet

- A Rare Cause of Chest Pain: Spontaneous Sternum Fracture: Ibrahim Sarbay, Halil DoganDocument5 pagesA Rare Cause of Chest Pain: Spontaneous Sternum Fracture: Ibrahim Sarbay, Halil DoganYuliSsTiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RadDocument5 pagesJurnal RadLapak Kamera KuNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Spinal InjuriesDocument8 pagesPediatric Spinal InjuriesAanchal KakkarNo ratings yet

- Berg 2012Document7 pagesBerg 2012Mario Espinosa GamezNo ratings yet

- Scs and C 201522Document5 pagesScs and C 201522noorhadi.n10No ratings yet

- Dasilva 2020Document4 pagesDasilva 2020Nazmi ZegarraNo ratings yet

- Original Article Original Article Original Article Original Article Original ArticleDocument4 pagesOriginal Article Original Article Original Article Original Article Original ArticlerutnomleniNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Trauma Ultrasound in Major Pelvic InjuryDocument5 pagesAccuracy of Trauma Ultrasound in Major Pelvic InjuryEvelyn GrandaNo ratings yet

- Geka K, Hernia Diafragmatika TraumatikDocument5 pagesGeka K, Hernia Diafragmatika TraumatikAndi Upik FathurNo ratings yet

- Gonfiotti A 2010 PDFDocument7 pagesGonfiotti A 2010 PDFOliver BlandyNo ratings yet

- Nakashima2013 Article CharacterizingTheNeedForTracheDocument7 pagesNakashima2013 Article CharacterizingTheNeedForTracheCristian GiovanniNo ratings yet

- Open Pneumothorax: The Spectrum and Outcome of Management Based On Advanced Trauma Life Support RecommendationsDocument4 pagesOpen Pneumothorax: The Spectrum and Outcome of Management Based On Advanced Trauma Life Support RecommendationsFatimahNo ratings yet

- 10 Aligizakis HadjipavlouDocument9 pages10 Aligizakis HadjipavlouI Made Dhita PriantharaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Unusual Cavitary Lesions of The Lung Analysis ofDocument6 pages2019 Unusual Cavitary Lesions of The Lung Analysis ofLexotanyl LexiNo ratings yet

- Dehghan 2018Document5 pagesDehghan 2018Nguyễn Văn HoạchNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PfnaDocument10 pagesJurnal PfnaDhea Amalia WibowoNo ratings yet

- Sternal Reconstruction After Post-Sternotomy Dehiscence and MediastinitisDocument9 pagesSternal Reconstruction After Post-Sternotomy Dehiscence and MediastinitisfabiolaNo ratings yet

- Radiologic Evaluation of Alternative Sites For Needle Decompression of Tension PneumothoraxDocument6 pagesRadiologic Evaluation of Alternative Sites For Needle Decompression of Tension PneumothoraxFeni WidyanitaNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Cervical Spine Fractures On CT: A Study in A Large Level I Trauma CenterDocument8 pagesIncidence of Cervical Spine Fractures On CT: A Study in A Large Level I Trauma CenterSubarna PaudelNo ratings yet

- An Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolDocument7 pagesAn Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolPepe pepe pepeNo ratings yet

- 3 Savall2015Document4 pages3 Savall2015Vivi DeviyanaNo ratings yet

- Journal Analysis of Fractured MandibleDocument5 pagesJournal Analysis of Fractured MandiblePrazna ShafiraNo ratings yet

- 293 592 1 SMDocument3 pages293 592 1 SMLaila munazadNo ratings yet

- K W: Abdominal Trauma, Morbidity, Mortality, Polytrauma, Severe Trauma, Thoracic Trauma, Thoraco-Abdominal Trauma, TraumaDocument4 pagesK W: Abdominal Trauma, Morbidity, Mortality, Polytrauma, Severe Trauma, Thoracic Trauma, Thoraco-Abdominal Trauma, TraumaYuyun Jenong18No ratings yet

- Demetria Des 2005Document6 pagesDemetria Des 2005María José Bueno MonteroNo ratings yet

- 5 6201509562231555914Document7 pages5 6201509562231555914Rahul ReddyNo ratings yet

- Increasing Time To Operation Is Associated With Decreased Survival in Patients With A Positive FAST Examination Requiring Emergent LaparotomyDocument5 pagesIncreasing Time To Operation Is Associated With Decreased Survival in Patients With A Positive FAST Examination Requiring Emergent LaparotomyEvelyn GrandaNo ratings yet

- Flail ChestDocument4 pagesFlail ChestittafiNo ratings yet

- Operative Versorgung Von Zentralen Talusfrakturen: Behandlungs-Ergebnisse Von 24 Fällen Im Mittel - Bis Langfristigen VerlaufDocument8 pagesOperative Versorgung Von Zentralen Talusfrakturen: Behandlungs-Ergebnisse Von 24 Fällen Im Mittel - Bis Langfristigen VerlaufFacundo ViláNo ratings yet

- 13-Viano D. C. 1989-Biomechanics of The Human Chest, Abdomen, and Pelvis in Lat PDFDocument22 pages13-Viano D. C. 1989-Biomechanics of The Human Chest, Abdomen, and Pelvis in Lat PDFTimothy BlankenshipNo ratings yet

- Reliability of Classification For Post Traumatic Ankle OsteoarthritisDocument6 pagesReliability of Classification For Post Traumatic Ankle OsteoarthritisDewi RoziqoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Risk Factors in Thoracic Trauma Patients With A Comparison of A Modern Trauma Centre: A Mono-Centre StudyDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Risk Factors in Thoracic Trauma Patients With A Comparison of A Modern Trauma Centre: A Mono-Centre StudyWahyu SholekhuddinNo ratings yet

- Clinical Studies on Classification and Treatment of Injuries Involving the Transverse Atlantal LigamentDocument7 pagesClinical Studies on Classification and Treatment of Injuries Involving the Transverse Atlantal LigamentJoão Pedro ZenattoNo ratings yet

- Errors in Emergency and Trauma RadiologyFrom EverandErrors in Emergency and Trauma RadiologyMichael N. PatlasNo ratings yet

- FormosJSurg51250-7751411 213154Document8 pagesFormosJSurg51250-7751411 213154Deddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- 1st AidDocument228 pages1st AidDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- 13multimodality ImagingDocument15 pages13multimodality ImagingDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Case Report Relaparotomy Two Years After Incisional Hernia Repair Using A Free Fascia Lata GraftDocument4 pagesCase Report Relaparotomy Two Years After Incisional Hernia Repair Using A Free Fascia Lata GraftDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- ComparisonDocument1 pageComparisonDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Fonc 11 680842Document11 pagesFonc 11 680842Deddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Anal Fissure 2Document24 pagesAnal Fissure 2Deddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

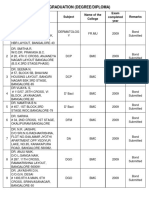

- Silabus Matematika 4 Sm1 Rev 2017Document48 pagesSilabus Matematika 4 Sm1 Rev 2017Ivan RismawanNo ratings yet

- Uro TraumaDocument28 pagesUro TraumaDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Quick Setup Guide for Wireless Projection SystemDocument8 pagesQuick Setup Guide for Wireless Projection SystemDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- PIN IKABDI 2022 Conference AgendaDocument23 pagesPIN IKABDI 2022 Conference AgendaDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- PIN IKABDI 2022 Conference AgendaDocument23 pagesPIN IKABDI 2022 Conference AgendaDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: Updates On WHO Classification, Clinicopathological Features and StagingDocument10 pagesAnaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: Updates On WHO Classification, Clinicopathological Features and StagingDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Pedia BLS GuideDocument32 pagesPedia BLS GuideDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Surgery and Acute Care Surgery: Evolution in The Eye of The StormDocument3 pagesTrauma Surgery and Acute Care Surgery: Evolution in The Eye of The StormDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Manage Chronic Pain Safely and EffectivelyDocument83 pagesManage Chronic Pain Safely and EffectivelyDeddy WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Obtaining Electrocardiogram (Ecg) : Clinical Nursing SkillsDocument2 pagesObtaining Electrocardiogram (Ecg) : Clinical Nursing SkillsSwillight meNo ratings yet

- Copptech: Successful Tests Against Sars-Cov-2Document2 pagesCopptech: Successful Tests Against Sars-Cov-2enologiacomNo ratings yet

- Massage For PromotingDocument7 pagesMassage For PromotingcaipillanNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 - PreventionDocument1 pageCovid-19 - PreventionKristel LavalleNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases in Pediatric Otolaryngology A Practical Guide by Tulio A. Valdez, Jesus G. VallejoDocument242 pagesInfectious Diseases in Pediatric Otolaryngology A Practical Guide by Tulio A. Valdez, Jesus G. VallejoNguyễn ThànhNo ratings yet

- San Antonio Elem. School: Contingency Plan ON Covid - 19Document12 pagesSan Antonio Elem. School: Contingency Plan ON Covid - 19Loraine Anna100% (2)

- NMHP KeralaDocument15 pagesNMHP KeralavijayalakshmiNo ratings yet

- Air Travel PregnancyDocument15 pagesAir Travel PregnancySharanjit DhillonNo ratings yet

- 906.9203 Rev01 1014SONICflex Brochure LR-1Document20 pages906.9203 Rev01 1014SONICflex Brochure LR-1jonathanmarceNo ratings yet

- Test Bank Advanced Health Assessment Clinical Diagnosis in Primary Care 6th Edition DainsDocument4 pagesTest Bank Advanced Health Assessment Clinical Diagnosis in Primary Care 6th Edition DainsCarlton Caughey100% (37)

- Social Case Study ReportDocument2 pagesSocial Case Study ReportKaren Laurin92% (12)

- Akatukunda Precious Final Research ProposalDocument46 pagesAkatukunda Precious Final Research ProposalIGA ABRAHAMNo ratings yet

- Ceftriaxone Compared With Sodium Penicillin G For Treatment of Severe LeptospirosisDocument9 pagesCeftriaxone Compared With Sodium Penicillin G For Treatment of Severe LeptospirosisFifi SumarwatiNo ratings yet

- Guidelines for Local Blood Donation and Convalescent Plasma ProgramsDocument17 pagesGuidelines for Local Blood Donation and Convalescent Plasma ProgramsEvrmc blood bankNo ratings yet

- Lumpy Skin DiseaseDocument99 pagesLumpy Skin DiseaseDaoud IssaNo ratings yet

- Candida AlbicansDocument14 pagesCandida AlbicansDhynda ARwolge CixicheuyyNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle Related Diseases HandoutsDocument1 pageLifestyle Related Diseases HandoutsJonathan RagadiNo ratings yet

- NBBS 1104v2 - Managment and Medico Legal StudiesDocument8 pagesNBBS 1104v2 - Managment and Medico Legal StudiesSYafikFikkNo ratings yet

- Herbal Remedies For Mouth Ulcer: A Review: KeywordsDocument7 pagesHerbal Remedies For Mouth Ulcer: A Review: KeywordsumapNo ratings yet

- Terapi ToxoplasmosisDocument9 pagesTerapi Toxoplasmosissarah disaNo ratings yet

- Marion Health Clinic Sees Patients On A Walk in Basis OnlyDocument1 pageMarion Health Clinic Sees Patients On A Walk in Basis OnlyAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- Case Report Jai 3Document8 pagesCase Report Jai 3EACMed Nursing Station 5th FloorNo ratings yet

- Cadi PDFDocument66 pagesCadi PDFpradeepsj ReddyNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Effective Nursing DocumentationDocument52 pagesGuidelines Effective Nursing DocumentationRichmon Joseph SantosNo ratings yet

- OralDocument3 pagesOralShaii Whomewhat GuyguyonNo ratings yet

- UK Causes of Death 2005Document334 pagesUK Causes of Death 2005curious4moreknowledgeNo ratings yet

- Cancer Simplified Lighter VersionDocument33 pagesCancer Simplified Lighter VersionRama KrisnaNo ratings yet

- Drug Abuse in PregnancyDocument91 pagesDrug Abuse in PregnancyCrystal Gayle Nario Sabado100% (1)

- Immunodeficiency Diseases: Professor Shahenaz M.HussienDocument17 pagesImmunodeficiency Diseases: Professor Shahenaz M.HussienVINAY KUMAR DHAWANNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka: Head and Neck Surgery 3Rd Edition. Mcgraw-Hill, San Francisco (HalDocument3 pagesDaftar Pustaka: Head and Neck Surgery 3Rd Edition. Mcgraw-Hill, San Francisco (HalBhisma SuryamanggalaNo ratings yet