Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 213.55.85.43 On Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

Uploaded by

Melkamu TamirOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 213.55.85.43 On Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

Uploaded by

Melkamu TamirCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychological Controversies in the Teaching of Science and Mathematics

Author(s): LEE S. SHULMAN

Source: The Science Teacher , SEPTEMBER 1968, Vol. 35, No. 6 (SEPTEMBER 1968), pp. 34-

38, 89-90

Published by: National Science Teachers Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24150776

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Science Teacher

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Psychological Controversies

in the Teaching of Science and Mathematics'

LEE S. SHULMAN

Professor of Educational Psychology and Medical Education

Michigan State University, East Lansing

the importance of basic associations or to consign Bruner and Gagné to irre

THE popular

the press

discovery hasofdiscovered

method facts in the service of the eventual vocable extremes. Their published

teaching.

mastering of principles and problem- writings are employed merely to char

It is by now, for example, an annual

ritual for the Education section of solving. acterize two possible positions on the

TIME magazine to sound a peal of Needless to say, there is considerable role of discovery in lear

praise for learning by discovery (e.g.,ambiguity over the use of the term each has expressed eloqu

TIME, December 8, 1967 [7]). discovery. One man's discovery ap- time in the recent past,

TIME's hosannas for discovery proach are by can easily be confused with In this paper I will firs

no means unique, reflecting as they another's

do guided learning curriculum if manner in which Brune

the educational establishment's the unwary observer is not alerted to respectively, describe the

general

tendency to make good things the preferred labels ahead of time. For some particular topic. U

seem

better than they are. Since even thisthereason I have decided to contrast examples as starting p

soundest of methods can be brought the twoto positions by carefully examin- then compare their posi

premature mortality through an ing the work of two men, each of whom spect to instructional

over

dose of unremitting praise, it becomesis considered a leader of one of these structional styles, readine

periodically necessary even for general

advo schools of thought. ing, and transfer of train

cates of discovery, such as I, to temper Professor Jerome S. Bruner of Har- then examine the implica

enthusiasm with considered judgment. vard University is undoubtedly the controversy for the proc

single person most closely identified tion in science and ma

The learning by discovery contro

with the learning-by-discovery position, the conduct of research

versy is a complex issue which can

easily be oversimplified. A recent His book,

vol The Process of Educa- process.

ume has dealt with many aspects of the tion [1], captured the spirit of discov

issue in great detail [8]. The contro ery in the new mathematics and science Instructional Example:

versy seems to center essentially about curricula and communicated it effec- Discovery Learning

the question of how much and what tively to professionals and laymen. His In a number of his papers, Jerome

kind of guidance ought to be provided thinking will be examined as repre- Bruner uses an instructional exampl

to students in the learning situation. sentative of the advocates of discovery from mathematics that derives from hi

Those favoring learning by discovery learning. collaboration with the mathematics ed

advocate the teaching of broad prin Professor Robert M. Gagné of the ucator, Z. P. Dienes [2],

ciples and problem-solving through University of California is a major A class is composed of

minimal teacher guidance and maximal force in the guided learning approach, old children who are the

opportunity for exploration and trial His analysis of The Conditions of some mathematics. In on

and-error on the part of the student. Learning [3] is one of the finest con- structional units, children ar

Those preferring guided learning em temporary statements of the principles troduced to three kinds of

phasize the importance of carefully of guided learning and instruction. of wood or "flats." The firs

sequencing instructional experiences I recognize the potential danger in- are told, is to be called

through maximum guidance and stress herent in any explicit attempt to polar- "unknown square" or "X s

ize the positions of two eminent schol- second flat, which is recta

1 Invited paper to the American Association for ars. My purpose is to clarify the called "1 X" or just X, si

the Advancement of Science, Division Q (Educa

tion), New York City. December 1967. dimensions of a complex problem, not long on one side and 1 l

34 THE SCIENCE TEACHER

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the outside world and some models or

templates that he already has in his

mind. For Bruner, it is rarely some

thing outside the learner that is dis

covered. Instead the discovery in

volves an internal reorganization of

1

□ D previously known ideas in order to es

unknown or 1 X or X 1 by 1 x + 2x +1-(x+1) (x+1) tablish a better fit betw

X square or 1 and the regularities of an encoun

which the learner has had to accom

other. The third flat is a small

modate. square

which is 1 by 1, and is called 1.

This is precisely the philosophy of

After allowing the children education

many op

we associate with Socrates.

portunities simply to play wi

materials and to get a feel for the

Bruner gives the children a problem.

slave boy is brou

He asks them, "Can you make larger

ing of what is inv

squares than this X square by using

area of aassquare

many of these flats as you want?" This

throughout this d

is not a difficult task for most children

teaching the boy

and they readily make another square

simply helping th

such as the one illustrated below. x

known.

Bruner almost a

focus on the pro

tion of materials. He describes the

child as moving through three levels of

representation. The first level is the

j5

x +o a\ enactive

Ux+1b = (xlevel, where. the child manipu

+ 4Hx+4)

lates materials directly. He

Bruner then asks them if they can tern. While the X's are progress

describe what they have done. They the rate of 2, 4, 6, 8, the ones are g

might reply, "We have one square X, 1,4,9,16, and on the right side

with two X's and a 1." He then asks equation the pattern is 1, 2, 3,

them to keep a record of what they have Provocative or leading question

done. He may even suggest a nota- often used Somatically to elicit th

tional system to use. The symbol Xn covery. Bruner maintains that, eve

could represent the square X, and a + the children are initially una

for "and." Thus, the pieces used could break the code, they will sen

be described as XD + 2X + 1. there is a pattern and try to discov

Another way to describe their new it. Bruner then illustrates how

square, he points out, is simply to de- pupils transfer what they have le

scribe each side. With an X and a 1 to working with a balance beam.

on each side, the side can be described youngsters are ostensibly learn

as X + 1 and the square as (X + 1) only something about quadratic eq

(X + 1 ) after some work with paren- tions, but more important, so

theses. Since these are two basic ways about the discovery of mathem

of describing the same square, they can regularities. inno

be written in this way: XG + 2X + 1 = The general learning process

(X + 1) (X + 1). This description, scribed by Bruner occurs in the fol

of course, far oversimplifies the pro- ing manner: First, the child finds

cedures used. larities in his manipulation of the acc

The children continue making materials that correspond with intu

squares and generating the notation for regularities he has already c

them. (See next diagram.) understand. Notice that what the chil

At some point Bruner hypothesizes does for Bruner is to find some sor

that they will begin to discern a pat- of match between what he is doing

SEPTEMBER 1968 35

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Instructional Example: principles, he must know specific con- fied in operational terms. Subsequently

Guided Learning cepts, and prerequisite to these are they can be task-analyzed; then they

Robert Gagné takes a very different particular simple associations or facts can be taught. Gagné would subscribe

approach to instruction. He begins discriminated from each other in a to the position that psychology has

with a task analysis of the instructional distinctive manner. He continues the been successful in suggesting ways of

objectives. He always asks the ques- analysis until he ends up with the teaching only when objectives have

tion, "What is it you want the learner fundamental building blocks of learn- been made operationally clear. When

to be able to do?" This capability he ing—classically or operantly condi- objectives are not clearly stated, the

insists, must be stated specifically and tioned responses. psychologist can be of little assistance.

behaviorally. Gagné, upon completing the whole He insists on objectives clearly stated

By capability, he means the ability maP °f prerequisites, would administer in behavioral terms. They are the cor

to perform certain specific functions pretests to determine which have al- nerstones of his position,

under specified conditions. A capabil- ready been mastered. Upon completing For Bruner, the emphasis is quite

ity could be the ability to solve a num- tbe diagnostic testing, the resulting different. The emphasis is not on the

ber series. It might be the ability to Patt;ern identifies precisely what must products of learning but on the proc

solve some problems in non-metric be tauëbt- This model is particularly esses. One paragraph from Toward a

geometry. conducive to subsequent programing of Theory of Instruction captures the spirit

This capability can be conceived of materials and programed instruction, of educational objectives for Bruner.

as a terminal behavior and placed at When prerequisites are established, a After discussing the mathematics ex

the top of what will eventually be a very fight teaching program or package ample previously mentioned, he con

complex pyramid. After analyzing the develops. eludes,

task, Gagné asks, "What would you Earlier, we discussed the influ- Finally, a theory of instruction seek

need to know in order to do that?" T et ences on Bruner. What influenced take account of the fact that a curric

us say that one could not complete the Gagné? This approach to teaching ^.Ts^L^Sslm

nature of the knower and of the knowledge

task unless he could first perform pre- comes essentially from a combination

requisite tasks a and b So a pyramid tbe neo-behaviorist psychological getting process. It is the enterprise p

beeins tradition and the task analysis model cellence where the line between the subject

6 ,1 a .1 t* matter and the method grows necessarily

that dominates the fields of militar

and industrial training. It was precise

this kind of task analysis that con-

. c l c 1 * of much prior intellectual activity. To in

tributed to successful programs of pilot . F ... ......

r ° r struct someone in these disciplines is not a

training in World War II. Gagné was matter of getting him to com

trained in the neo-behaviorist tradition to mind; rather, it is to teach him to par

and spent the major portion of his early ticipate in the process that makes possible

, . _ ... the establishment of knowledge. We teach

career as an Air Force psychologist. a subject; not to produ

But in order to perform task a, one braries from that subject, but rather to get

must be able to perform tasks c and d Nature Of Objectives a ,sftudent to. !hink mathema

r self, to consider matters as a historian does,

and for task b, one must know e, f, The posi

and g. take very different points of view with getting. Knowing is a process, not a prod

respect to the objectives of education. uct• ^2' p- 72' (Italics mine)

This is one of the major reasons why Speaking to the same issue, Gagn

most attempts at evaluating the relative position is clearly different,

effectiveness of these two approaches Obviously, strategies are important

have come to naught. They really problem solving, regardless of the conte

cannot agree on the same set of ob- of the problem. The suggestion from so

. ^ . . , . , . writings is that they are of overriding im

jec ives. ny attempt to ask which IS portance as a goal of educ

better—Michigan State's football team should not formal instructio

or the Chicago White Sox—will never have the aim of teaching

So one builds a very complex pyramid succeed. The criteria for success are t0 l!"nk ? ,!f s

. .. .. . , taught, would not this produce people who

of prerequisites to prerequisites to the different,

objective which is the desired capability, have them

Gagné has developed a model for peting aga

j- „ ., J-« . i , „ , „ _ , , . aims expressed, it is exceedingly doubtful

discussing the different levels of such For Gagne, or the programed

a hierarchy. If the final capability de- struction position which can b

sired is a problem-solving capability, rived from him, the objec

the learner first must know certain instruction are capabilities. The

principles. But to understand those behavioral products that can be

36 THE SCIENCE TEACHER

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

knowledge. Knowing a set of strategies is determined entirely by the program. When the child is capable of d and e

not all that is required for thinking; it is

(Here the term "program" is used in above, he is by definition ready to learn

not even a substantial part of what is

needed. To be an effective problem solver, a broad sense, not necessarily simply b. Until then he is not ready. Gagné

the individual must somehow have acquired a series of frames.) is not concerned with genetically de

masses of structurally organized knowledge. For Bruner much less system or velopmental considerations. If the

Such knowledge is made up of content prin

ciples, not heuristic ones. [3, p. 170] (Italics order is necessary for the package, al- at age five does not have the con

mine) though such order is not precluded. In of the conservation of liquid vo

general Bruner insists on the child it is not because of an unfolding

While for Bruner "knowing is a

manipulating materials and dealing mind; he just has not had the

process, not a product," for Gagné,

with incongruities or contrasts. He will sary prior experiences. Ensure

"knowledge is made up of content prin

always try to build potential or emer- he has acquired the prerequi

ciples, not heuristic ones." Thus,

gent incongruities into the materials, haviors, and he will be able t

though both espouse the acquisition of

Robert Davis calls this operation "tor- serve [4],

knowledge as the major objective of

pedoing" when it is initiated by the For Piaget (and Bruner) the c

education, their definitions of knowl

teacher. He teaches a child something is a developing organism, p

edge and knowing are so disparate that

until he is certain the child knows it. through cognitive stages that are

the educational objectives sought by

Then he provides him with a whopper logically determined. These stage

each scarcely overlap. The philosophi

of a counterexample. This is what more or less age-related, althou

cal and psychological sources of these

differences will be discussed later in

Bruner does constantly—providing different cultures certain stage

contrasts and incongruities in order to come earlier than others. To ide

this paper. For the moment, let it be

get the child, because of his discom- whether the child is ready to lear

noted that when two conflicting ap

fort, to try to resolve this disequilib- particular concept or princip

proaches seek such contrasting objec

rium by making some discovery (cog- analyzes the structure of tha

tives, the conduct of comparative edu

nitive restructuring). This discovery taught and compares it with w

cational studies becomes extremely

difficult.2

can take the form of a new synthesis already known about the cog

or a new distinction. Piaget, too, main- structure of the child at that a

tains that cognitive development is a they are consonant, it can be

Instructional Styles process of successive disequilibria and if they are dissonant, it cannot,

Implicit in this contrast is a differ equilibria. The child, confronted by a Given this characterization

ence in what is meant by the very new situation, gets out of balance and two positions on readiness, to

words learning by discovery. For must accommodate to achieve a new one would you attribute the fo

Gagné, learning is the goal. How abalance by modifying the previous statement? ". . . any subject c

behavior or capability is learned iscognitive a structure. taught effectively in some intellectually

function of the task. It may be by dis Thus, for Gagné, instruction is a honest form to any child at any stage

covery, by guided teaching, by pracsmoothly guided tour up a carefully of development." While it sounds like

tice, by drill, or by review. The focus constructed hierarchy of objectives; Gagné, you recognize that it isn't—it's

is on learning and discovery is but one for Bruner, instruction is a roller- Bruner! [2, p. 33] And in this same

way to learn something. For Bruner,coaster ride of successive disequilibria chapter he includes an extensive dis

it is learning by discovery. The methodand equilibria until the desired cog- cussion of Piaget's position. Essen

of learning is the significant aspect. nitive state is reached or discovered, tially he is attempting to translate

For Gagné, in an instructional pro Piaget's theories into a psychology of

gram the child is carefully guided. HeReadiness instruction.

may work with programed materials or The guided learning point of view, M

a programed teacher (one who followsrepresented by Gagné, maintains that

quite explicitly a step-by-step guide).readiness is essentially a function of the

The child may be quite active. He ispresence or absence of prerequisite t

not necessarily passive; he is doing

learning. Bruner could make such a statement

things, he is working exercises, he is in the light of Piaget's experiments. If

solving problems. But the sequence is Bruner meant the statement literally;

i.e., any child can learn anything, then

2 Gagné has modified his own position somewhat

since 1965. He would now tend to agree, more or it just is not true! There are always

less, with Bruner on the importance of processes things a child cannot learn, especially

or strategies as objectives of education. He has

not, however, changed his position regarding the not in an intellectually honest way. If

role of sequence in instruction, the nature of readi

ness, or any of the remaining topics in this he means it homiletically, i.e., we can

paper. [5] The point of view concerning specific take almost anything and somehow re

behavioral products as objectives is still espoused

by many educational theorists and Gagné's earlier say it, reconstruct it, restructure it so

arguments are thus still relevant as reflections of

that position. it now has a parallel at the child's level

SEPTEMBER 1968 37

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of cognitive functioning, then it may individual and on the subject matter. We For Bruner, the same diagram may

be a truism. still need a great deal of research to know appropriate, but the direction of the

what the optimal time would be. [6, p. 82] , , , , , IT ,

I believe that what Bruner is saying, arrow would be changed. He has a

and it is neither trivial nor absurd, is The question that has not been pUph begin with problem solving. This

that our older conceptions of readinessanswered, and which Piaget whimsically process is analogous to teaching some

have tended to apply Piagetian theory calls the American question, is the one tQ swjm by throwing him into deep

in the same way as some have for empirical experimental question: To water. The theory is that he will learn

generations applied Rousseau's. The what extent it is possible through a t^e fundamentals because he needs

old thesis was, "There is the child— Gagnéan approach to accelerate what them The analogy is not totally mis

he is a developing organism, with in Piaget maintains is the invariant clock- begotten. In some of the extreme dis

variant order, invariant schedule. Here,work of the order? Studies being con- covery approaches we lose a lot of

too, is the subject matter, equally hal ducted in Scandinavia by Smedslund pupils by mathematical or scientific

lowed by time and unchanging. We and in this country by Irving Sigel, drowning. As one goes to the extreme

take the subject matter as our starting Egon Mermelstein, and others are at- of this position, he runs the risk of

point, watch the child develop, and tempting to identify the degree to which some drownings. For Gagné, the se

feed it in at appropriate times as he such processes as the principle of con- quence is from the simple to the com

reaches readiness." Let's face it; that servation of volume can be accelerated. pjex; for Bruner one starts with the

has been our general conception of If I had to make a broad generaliza- complex and plans to learn the simple

readiness. We gave reading readiness tion, I would have to conclude that at components in the context of working

tests and hesitated to teach the pupil this point, in general, the score for with the compiex.

reading until he was "ready." The those who say you cannot accelerate is js unclear whether Bruner sub

notion is quite new that the reading somewhat higher than the score for scribes to his position because of his

readiness tests tell not when to begin those who say that you can. But the concept of the nature of learning or

question is far from resolved, we need jor strictly motivational reasons. Chil

teaching the child, but rather what has

to be done to get him more ready. We many more inventive attempts to ac- (jren may be motivated more quickly

used to just wait until he got ready. celerate cognitive development than we when given a problem they cannot

What Bruner is suggesting is that we have had thus far. There remains the soiVe, than they are when given some

must modify our conception of readi question of whether such attempts at little things to learn on the promiSe that

ness so that it includes not only the experimental acceleration are strictly of jf they learn these well, three weeks

child but the subject matter. Subject interest for psychological theory, or from now they will be able to solve an

matter, too, goes through stages of have important pedagogical implica- exciting problem. Yet, Bruner clearly

readiness. The same subject matter tions as well a question we do not maintains that learning things in this

can be represented at a manipulative have space to examine here. fashion also improves the transfer

or enactive level, at an ikonic level, ability of what is learned. It is to a

and finally at a symbolic or formal Sequence of the Curriculum consideration of the issue of transfer

level. The resulting model is Bruner's The implications for the sequence of training that we now turn,

concept of a spiral curriculum. the curriculum growing from these two

Piaget himself seems quite dubious positions are quite different. For Transfer of Training

over the attempts to accelerate cogni Gagné, the highest level of learning is j0 examine the psychologies of

tive development that are reflected in problem solving; lower levels involve learning of these two positions in any

many modern math and science cur facts, concepts, principles, etc. Clearly, )Qn(] Gf comprehensive form would re

ricula. On a recent trip to the United for Gagné, the appropriate sequence in quire greater attention than can be

States, Piaget commented, learning is, in terms of the diagram devoted here, but we shall consider one

... we know that it takes nine to twelve below, from the bottom up. One be- concept—that of transfer of training,

gins

months before babies develop the notion with simple prerequisites and This js probably the central concept,

that an object is still there even when a

works up, pyramid fashion, to the com- or should be, in any educationally rele

screen is placed in front of it. Now kittens

go through the same stages as children, all plex capability sought. vant psychology of learning.

the same sub-stages, but they do it in three Gagné considers himself a conserva

months—so they're six months ahead of tive on matters of transfer. He states

babies. Is this an advantage or isn't it? We that "transfer occurs because of the

can certainly see our answer in one sense.

The kitten is not going to go much further. occurrence of specific identical (or

a:

The child has taken longer, but he is capable UJ highly similar) elements within devel

of going further, so it seems to me that the Z

3 opmental sequences" [4, p. 20], To

nine months probably were not for nothing. 0£

It's probably possible to accelerate, but CO

the extent that an element which has

maximal acceleration is not desirable. There been learned, be it association, concept,

seems to be an optimal time. What this

optimal time is will surely depend upon each Continued on page 89

38 THE SCIENCE TEACHER

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Psychological Controversies— other manner—which will transfer This is a pessimistic view, and I hope

Continued from page 38 across grossly different kinds of tasks, that future studies might find it flawed.

or principle, can be directly employed is transfer of training superior Synthesis Or Selection

in a new situation, transfer will occur. |n the discovery situation when the Need we eternally code these as tWQ

If the new context requires a behavior gaming of principles is involved. alternatives_discovery versus exposi.

substantially different from the specific There are two kinds of transfer posi- tQry teaching_or can we> without be_

capability mastered earlier, there will tlvÇ transfer and negative transfer. We . heretical manage to keep both of

be no transfer caU something positive transfer when .

no uausiei. =■ r these in our methodological repertories

.v , j v mastery of task X facilitates mastery of , . , „

Bruner, on the other hand, sub- ■' , as mathematics and science educators?

*■ i_ At c task Y. Negative transfer occurs when

scribes to the broadest theories of task x Qf John Dewe

ransfer of training. Bruner believes ^ y positive .g & familjar piclous wh

mm one m notion for us. Negative transfer can be troversy betw

from one learning situation to another. exemDbfied bv a niece of advice base- position

Broad transfer of training occurs when . the other was totallv in error The

6 . t , ball coaches often give their players. me otner was totally in

one can identify in the structures of They ^ them nQt to pJay golf during classic example of t

ÎnW fundamentally ^ baseba]1 because ^ base. graph Experience and Ed

lernen well pan h Tu'î'♦ bal1 swin8 and the golf swing involve which he examines the

other,1

other t TV°

subject totaI1y

mutters different

within thut dis~muscles andtpschps

tion l~)pwev body traditional versus

nc that whpnpvpr progr

. ,. , , „ movements. Becoming a better golf uon- uewey teacnes us tnat wnenever

cipline and to other disciplines as well sw-nger interferes with the basebal, we confront this kind of contro

He gives examples such as the concept swing Iq psychological terms there is we must look for the possib

of conservation or balance. Is it not negatiye transfer between golf and each position is massively butt

possible to teach balance of trade in basebajj a brilliant half-truth from whic

economics in such a way that when ..... , , . . . r trapolated the whole cloth of an

ecological balance is considered, pupils . what ls needed for positive transfer cational philosophy xhat is

see the parallel? This could then be f to minimize all possible interference. a idea wgars ^ ag ^ a

extended to balance of power in politi- Ia transfer of training there are some insjst ^ R

cal science, or to balancing equations. ways in which the tasks transferred to propriate domain

tr . , . c D . are like the ones learned first, but in

th I TP°h i1 f'tn rTer' !S other ways they are different. So trans- As educ

the broad transferability of the knowl- ^ always involyes striking a ba,ance impor

edge - getting Processes — strategies, thcse conflicting potentials for under whi

heuristics and the like—a transfer ^ ^ be applied most

whose viability leaves Gagne with deep disCQVcry methodS; learners may trans. must

feelings of doubt. This is the question fer more easjjy becausg they learn the lives

of whether earning by discovery leads immediate Mngs /gyy weR They may versy ca

to the ability to discover, that is, the ^ Jeam ^ brQad strokes a prin_ of which

development of broad inquiry com- ^ which .g ^ mogt critical at the leve

petencies in students. for ^ judgments. Given one set of goals,

What does the evidence from em- wg]1 the detailed appiication of that cIearly the Positlon Gagné ad

pineal studies of this issue seem to jfic principle> which could interfere presently has more evidence

demonstrate? The findings are not all somewhat with successful remote favor; 8lven another set of Soa

that consistent. I would generalize transfer 's no question but that Bruner's posi

them by saying that most often guided , . .. . tion is preferable to Gagné's.

. If this formulation is correct, we are

learning or expository sequences seem ^ {o find

to be superior methods or achieving ^ ^ for tremen

immediate learning. With regard to leaming of products

long-term retention the results seem ^ because we are d

equivocal, with neither approach con- system jn which

sistently better. Discovery learning ap- Jq ^

proaches appear to be superior when transfer is re

the criterion of transfer of principles to . " that are well organized so that we can

new situations is employed [9], Notably e ms ructor. may have to decide take notes in a systematic manner,

absent are studies which deal with the which 1S more important an immedi- 0thers of us like nothing better than a

question of whether general techniques, ate specific product or broad transfer free-flowing bull session; and each of

strategies, and heuristics of discovery and choose his subsequent teaching us ;s convinced that we learn more in

can be learned—by discovery or in any method on the basis of that decision, our preferred mode than the others

SEPTEMBER 1968 89

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

learn in theirs. Individual differences Theories of Learning ence education today, it is that rarely

in learning styles are major determi

and the Science and have any disciplines been so rich in

nants of the kinds of approaches that theory and brilliant ideas. But we must

work best with different children.

Mathematics Curriculum

seriously consider the admonition of

Yet this is something we have in There is a growing psychology of Ivan Pavlov, the great Russian psy

general not taken into consideration at learning that is finally becoming chologist,

mean who is said to have told his

all in planning curricula—and for very ingful to curriculum construction and

students the following:

good reasons. As yet, we do not have educational practice. Children are be Ideas and theories are like the wings of

ing studied as often as rats, and birds; they allow man to soar and to climb

class

any really valid ways of measuring to the heavens. But facts are like the atmos

these styles. Once we do, we will have rooms as often as mazes. Research phere against which those wings must beat,

a powerful diagnostic tool. Subject with lower animals has been extremely and without which the soaring bird will

matter, objectives, characteristics of useful in identifying some principles surely plummet

of back to earth.

children, and characteristics of the learning that are so basic, so funda

References

teacher are all involved in this educa mental, so universal that they apply to Bruner, Jerome S. The Process of Edu

tional decision. Some teachers are no any fairly well-organized blob of pro cation. Harvard University Press, Cam

toplasm. But there is a diminishing

more likely to conduct a discovery bridge, Massachusetts. 1960.

Bruner, Jerome S. Toward a Theory of

return

learning sequence than they are to go in this approach insofar as trans Instruction. Belknap Press, Cambridge,

frugging at a local nightclub. fer to educational practice is con Massachusetts. 1966.

cerned. Today, a developing, em

There appear to be middle routes Gagné, Robert M. The Conditions of

pirically based psychology of learning Learning. Holt, Rinehart & Winston,

as well. In many of the experimental New York. 1965.

for homo sapiens olfers tremendous Gagné, Robert M. Contributions of

studies of discovery learning, an experi

mental treatment labeled guided dis promise. But it can never be immedi Learning to Human Development. Ad

ately translatable into a psychology of dress of the Vice-President, Section I

covery is used. In guided discovery, (Psychology), American Association for

the subjects are carefully directed down the teaching of mathematics or science.

the Advancement of Science, Washing

Mathematics and science educators ton, D.C. December 1966.

a particular path along which they are

must not make the mistake that the Gagné, Robert M. Personal communica

called upon to discover regularities and tion. May 1968.

solutions on their own. They are pro reading people have made and con Jennings, Frank G. "Jean Piaget: Notes

tinue to make. The reason that the

vided with cues in a carefully pro on Learning." Saturday Review, May

gramed manner, but the actual state psychology of the teaching of reading

20, 1967, p. 82.

"Pain

the & Progress in Discovery." TIME,

ment of the principle or problem solu has made such meager progress in December 8, 1967, pp. 110 ff.

tion is left up to them. Many of the last 25 years is that the reading peo Shulman, Lee S. and Keislar, Evan R.,

ple have insisted on being borrowers. Editors. Learning by Discovery: A

well-planned Socratic dialogues of our

Something new happens in Critical Appraisal. Rand-McNally, Chi

linguistics

fine teachers are forms of guided dis cago. 1966.

covery. The teacher carefully leads theand within three years a linguistic read Worthen, Blaine R. "Discovery and Ex

pupils into a series of traps from which ing series is off the press. It ispository

an Task Presentation in Elemen

they must now rescue themselves. attempt to bootleg an idea from one

tary Mathematics." Journal of Educa

tional Psychology Monograph Supple

field and put it directly into another

In the published studies, guided dis ment 59: 1, Part 2; February 1968.

without the necessary intervening steps

covery treatments generally have done

of empirical testing and research.

quite well both at the level of imme

Mathematics and science education New Magazine Reviews

diate learning and later transfer. Per

are in grave danger of making that Science Books for Children

haps this approach allows us to put the

Bruner roller-coaster of discovery onsame error, especially with the work

The Children's Science Book Review

of Piaget and Bruner. What is neededCommittee, a nonprofit organization

the well-laid track of a Gagné hier sponsored by the Harvard Graduate

archy. now are well-developed empirically

School of Education and the New Eng

based psychologies of mathematics and land Round Table of Children's Li

Thus, the earlier question of which

science learning. Surely they will grow

brarians, announces the inception of

is better, learning by discovery or

out of what is already known about theAppraisal, a new periodical devoted to

guided learning, now can be restated the belief that science books for children

psychology of learning in general, but

in more functional and pragmatic deserve the same careful selection as do

terms. Under what conditions are each

they must necessarily depend upon

literary works. In Appraisal each book

people like yourselves, your students,

is given two reviews: one by a librarian

of these instructional approaches, some

and your colleagues who are interested

and one by a subject-matter specialist.

sequence or combination of the two,

of some synthesis of them, most likely in mathematics and science conductingSubscriptions ($3 domestic, $3.75 for

eign) should be sent to Appraisal, Chil

to be appropriate? The answers to suchempirical studies of how certain spedren's Science Book Review Committee,

questions ought to grow out of quite cific concepts are learned under certain

Harvard Graduate School of Education,

comprehensive principles of human specific conditions with certain specific207 Byerly Hall, Appian Way, Cam

learning. Where are we to find such kinds of pupils. If anything is true bridge, Massachusetts 02138. Published

principles? about the field of mathematics and sei three times a year; single copies, $1.25.

90 THE SCIENCE TEACHER

This content downloaded from

213.55.85.43 on Tue, 06 Sep 2022 08:19:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Paradigms of Gifted Education: A Guide for Theory-Based, Practice-Focused ResearchFrom EverandParadigms of Gifted Education: A Guide for Theory-Based, Practice-Focused ResearchNo ratings yet

- God's Design For Earth Teachers SampleDocument15 pagesGod's Design For Earth Teachers Samplesi_miaomiaoNo ratings yet

- Seven Concepts For Effective Teaching: Astronomy Education Review December 2011Document4 pagesSeven Concepts For Effective Teaching: Astronomy Education Review December 2011Aamir khanNo ratings yet

- The Unified Learning Model: How Motivational, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences Inform Best Teaching PracticesFrom EverandThe Unified Learning Model: How Motivational, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences Inform Best Teaching PracticesNo ratings yet

- Bruner, J. S. (1966) - Toward A Theory of Instruction (Vol. 59) - Harvard University Press.Document28 pagesBruner, J. S. (1966) - Toward A Theory of Instruction (Vol. 59) - Harvard University Press.memen azmiNo ratings yet

- Instructional Sequence Matters, Grades 9–12: Explore-Before-Explain in Physical ScienceFrom EverandInstructional Sequence Matters, Grades 9–12: Explore-Before-Explain in Physical ScienceNo ratings yet

- Pragmatism Paper Final EditDocument8 pagesPragmatism Paper Final Editapi-679217165No ratings yet

- Schwartz Et AlDocument22 pagesSchwartz Et AlAnthony PetrosinoNo ratings yet

- Jerome Bruner: For N515-By Leslie WagleDocument19 pagesJerome Bruner: For N515-By Leslie WagleSantos SantosokuNo ratings yet

- Bruners Learning TheoryDocument5 pagesBruners Learning TheoryvimiraNo ratings yet

- Instructional Sequence Matters, Grades 3-5: Explore Before ExplainFrom EverandInstructional Sequence Matters, Grades 3-5: Explore Before ExplainNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research: An Introduction: Bruce KochisDocument4 pagesClassroom Research: An Introduction: Bruce KochisMmarita DMaguddayaoNo ratings yet

- Biology Made Real: Ways of Teaching That Inspire Meaning-MakingFrom EverandBiology Made Real: Ways of Teaching That Inspire Meaning-MakingNo ratings yet

- On Teaching Science: Principles and Strategies That Every Educator Should KnowFrom EverandOn Teaching Science: Principles and Strategies That Every Educator Should KnowRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Mathematics in Nature, Space and Time J. Blackwood Floris BooksDocument204 pagesMathematics in Nature, Space and Time J. Blackwood Floris BooksSvetlana Dim100% (4)

- How to Teach Anything: Break Down Complex Topics and Explain with Clarity, While Keeping Engagement and MotivationFrom EverandHow to Teach Anything: Break Down Complex Topics and Explain with Clarity, While Keeping Engagement and MotivationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Teaching Genius: Redefining Education with Lessons from Science and PhilosophyFrom EverandTeaching Genius: Redefining Education with Lessons from Science and PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Scientific Approach To EducationDocument7 pagesScientific Approach To EducationYuuki RealNo ratings yet

- Educ 5312-Research Paper Template 1Document9 pagesEduc 5312-Research Paper Template 1api-534834592No ratings yet

- 1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningDocument7 pages1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningNohaNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Roy 2014 - PortfolioDocument13 pagesSynthesis Roy 2014 - Portfolioapi-241824985No ratings yet

- What if everything you knew about education was wrong?From EverandWhat if everything you knew about education was wrong?Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Team Teaching at the College Level: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesFrom EverandTeam Teaching at the College Level: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesNo ratings yet

- Research On Learning: Potential For Improving College Ecology TeachingDocument8 pagesResearch On Learning: Potential For Improving College Ecology TeachingMajo Fiquitiva LondoñoNo ratings yet

- The Challenges of Culture-based Learning: Indian Students' ExperiencesFrom EverandThe Challenges of Culture-based Learning: Indian Students' ExperiencesNo ratings yet

- Discovery LearningDocument10 pagesDiscovery Learningumar backrieNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Teaching: Folk PsychologyDocument6 pagesConstructivist Teaching: Folk PsychologyLidia FloresNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Teaching Practice: Guide for University and College LecturersFrom EverandMathematics Teaching Practice: Guide for University and College LecturersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ DifficultiesDocument4 pagesRationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ Difficultiesapi-356513456No ratings yet

- Our Place in the Universe - II: The Scientific Approach to DiscoveryFrom EverandOur Place in the Universe - II: The Scientific Approach to DiscoveryNo ratings yet

- Energy Think in Two Domains Solomon1983Document12 pagesEnergy Think in Two Domains Solomon1983Alba Margarita Picos LeeNo ratings yet

- Philosophers of Education (Maymay)Document3 pagesPhilosophers of Education (Maymay)Rona Mae Talamera0% (1)

- Learning Spaces BookChap2Document20 pagesLearning Spaces BookChap2Huzefa SaifuddinNo ratings yet

- Prereading 1Document5 pagesPrereading 1Jenny Joo Yeun OhNo ratings yet

- Ambriz Assignment Week 3Document7 pagesAmbriz Assignment Week 3api-515368118No ratings yet

- Educational Leadership - 2017Document6 pagesEducational Leadership - 2017Afrasiab KhanNo ratings yet

- Context Goals Beliefs and Learning MathDocument9 pagesContext Goals Beliefs and Learning MathGreySiNo ratings yet

- Situated Cognition and The Culture of LearningDocument12 pagesSituated Cognition and The Culture of LearningYaniHuayguaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Mathematics Problems Prepares Children To Learn From InstructionDocument19 pagesExploring Mathematics Problems Prepares Children To Learn From InstructionamigosNo ratings yet

- The Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction: Nell K. Duke, Alessandra E. Ward, P. David PearsonDocument10 pagesThe Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction: Nell K. Duke, Alessandra E. Ward, P. David Pearsontan thanhtanNo ratings yet

- Hands-On Learning 1Document6 pagesHands-On Learning 1Reen ShazreenNo ratings yet

- Science Simplified: Simple and Fun Science (Book A, Grades K-2): Learning by DoingFrom EverandScience Simplified: Simple and Fun Science (Book A, Grades K-2): Learning by DoingNo ratings yet

- Teacher Guide for Sugar Falls: Learning About the History and Legacy of Residential Schools in Grades 9–12From EverandTeacher Guide for Sugar Falls: Learning About the History and Legacy of Residential Schools in Grades 9–12No ratings yet

- Handbook of the Learning Sciences-頁面-1,22-37Document17 pagesHandbook of the Learning Sciences-頁面-1,22-37leonaaa2001No ratings yet

- Experiential Learning From Discourse Model To ConversationDocument6 pagesExperiential Learning From Discourse Model To Conversationcarlos hernan ramirez poloNo ratings yet

- Accessible Elements: Teaching Science Online and at a DistanceFrom EverandAccessible Elements: Teaching Science Online and at a DistanceNo ratings yet

- Science Simplified: Simple and Fun Science (Book F, Grades 5-7): Learning by DoingFrom EverandScience Simplified: Simple and Fun Science (Book F, Grades 5-7): Learning by DoingNo ratings yet

- An Annotated Bibliography: "Shut Up and Calculate" Versus "Let's Talk" Science Within A TELEDocument7 pagesAn Annotated Bibliography: "Shut Up and Calculate" Versus "Let's Talk" Science Within A TELEDana BjornsonNo ratings yet

- Civics Lesson 6 How Can We Get Involved in Our Local GovernmentDocument4 pagesCivics Lesson 6 How Can We Get Involved in Our Local Governmentapi-252532158No ratings yet

- BLOG POST BYOB' A Beginner's Guide To Meditating Written For A Spoonful of Sukha,' Personal Mindfulness Blog in 2016Document3 pagesBLOG POST BYOB' A Beginner's Guide To Meditating Written For A Spoonful of Sukha,' Personal Mindfulness Blog in 2016api-280615080No ratings yet

- Mind and Brain - A Critical Appraisal of Cognitive Neuroscience PDFDocument526 pagesMind and Brain - A Critical Appraisal of Cognitive Neuroscience PDFLomer AntoniaNo ratings yet

- Ict Group Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesIct Group Lesson Planapi-347783593No ratings yet

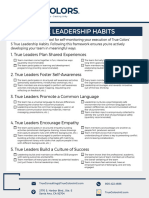

- TC True Leadership Habits Interactive - 2023Document1 pageTC True Leadership Habits Interactive - 2023drionutcostacheNo ratings yet

- Junaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveDocument1 pageJunaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- MSUKU NEW Research ReportDocument65 pagesMSUKU NEW Research ReportFrank AlexanderNo ratings yet

- SORS 2002 Survey of Reading Strategies PDFDocument2 pagesSORS 2002 Survey of Reading Strategies PDFkaskarait100% (13)

- Unit 4Document15 pagesUnit 4s@nNo ratings yet

- Why Does Social Media Affect Kids?Document6 pagesWhy Does Social Media Affect Kids?Safwara SindhaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between The Big Five Personality Traits and Academic MotivationDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between The Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Motivationparadiseseeker35No ratings yet

- All 3 Answers in OneDocument4 pagesAll 3 Answers in OneUnushka ShresthaNo ratings yet

- How Fake News Affects The Sense of Nationalism Among FilipinosDocument2 pagesHow Fake News Affects The Sense of Nationalism Among FilipinosPatricia Ann DavidNo ratings yet

- Human Behavior-Lesson (Chapter 1 To 4)Document13 pagesHuman Behavior-Lesson (Chapter 1 To 4)Pasiphae Xinnea Clarkson100% (1)

- Effects of Social MediaDocument36 pagesEffects of Social MediaGilliana Kathryn Bacharo100% (3)

- Professional Inquiry ProjectDocument13 pagesProfessional Inquiry Projectapi-427518965No ratings yet

- Zifferblatt ArchitectureHumanBehavior 1972Document5 pagesZifferblatt ArchitectureHumanBehavior 19720andreeva.polina0No ratings yet

- Critique Paper: Bullying: Students Themselves May Be The Key To Solving ProblemsDocument3 pagesCritique Paper: Bullying: Students Themselves May Be The Key To Solving ProblemsBlessed ValdezNo ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN Year 4 Reading Good ValuesDocument3 pagesLESSON PLAN Year 4 Reading Good ValuesSirAliffNo ratings yet

- Topic / Lesson Name Summary and Paraphrasing of Academic Text Content StandardsDocument4 pagesTopic / Lesson Name Summary and Paraphrasing of Academic Text Content Standardsjaja salesNo ratings yet

- Basic of Sales ManagementDocument20 pagesBasic of Sales ManagementImran Malik80% (5)

- Seedfolks Novel Engineering Lesson Plan AssignmentDocument5 pagesSeedfolks Novel Engineering Lesson Plan Assignmentapi-252147761No ratings yet

- Programacion 2 EsoDocument63 pagesProgramacion 2 EsoNevado RocíoNo ratings yet

- Canguilhem-The Brain and Thought PDFDocument12 pagesCanguilhem-The Brain and Thought PDFAlexandru Lupusor100% (1)

- Critical Approaches To LiteratureDocument3 pagesCritical Approaches To LiteratureMike EspinosaNo ratings yet

- PT Cpi Web Evaluation: 1. Professional Practice - SafetyDocument6 pagesPT Cpi Web Evaluation: 1. Professional Practice - Safetyapi-468012516No ratings yet

- RIZALDocument4 pagesRIZALJULIENE MALALAYNo ratings yet

- Direct Staff: AND Notre Dame and Northern State Hospital Developmental Disabilities CenterDocument17 pagesDirect Staff: AND Notre Dame and Northern State Hospital Developmental Disabilities CentertyfanyNo ratings yet

- Identity, Image and Issue Interpretation During Strategic Change in AcademiaDocument35 pagesIdentity, Image and Issue Interpretation During Strategic Change in AcademiafamastarNo ratings yet

- Sports Module 1Document20 pagesSports Module 1Shiva 05No ratings yet