Professional Documents

Culture Documents

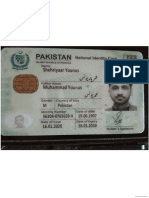

2022 - 10 - 19 8 - 54 PM Office Lens

2022 - 10 - 19 8 - 54 PM Office Lens

Uploaded by

Muhammad Noman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views5 pagesPmofc

Original Title

2022_10_19 8_54 PM Office Lens

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPmofc

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views5 pages2022 - 10 - 19 8 - 54 PM Office Lens

2022 - 10 - 19 8 - 54 PM Office Lens

Uploaded by

Muhammad NomanPmofc

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

ee

ism of assumptions and power of the modes ;

that Ga agents, producers or consumers, is the ee

uelson’s position’ #

os ihe behaviour of ae econ

important attribute of « move’: chat whatis the most important attributeofa

Most economists take the Posto tone puts the model. Predictive performances

depends on its purpose, the Oe ode! is forecasting the effects of a certain change

important when the purpose © tions and explanatory power are important features ¢f

a variable, Realism of assuthh jel is the explanation of why a system behaves as it dec

model ifthe purbos $ fulfil both criteria: it should be the best predictor of the behavien,

Hdeally See vide the most complete explanation of this behaviour. However.

of the system ely met in practice, one reason being that the relationships in a mode)

sarge continue over time. Another reason is the skills of model-builders. A person

that gives the best forecasts does not necessarily also provide the most accurate ex.

planations. The model-builder must define the primary purpose of his model before

constructing it. He should then build the model in such a way as to best attain its pri

objective, even if this course of action means that the model will not be suitable for other

secondary objectives. In particular, the number and nature of the assumptions of the

model, its degree of detail (or level of aggregation) and the amount of information it can

yield will depend on the purpose of building the model. ;

The purpose of the theory of the firm is to provide models for the analysis of the de-

cision-making in the firm in various market structures. A theory of the firm should ex-

plain how the decisions of the firm are taken: how the firms set their price, decide the

level and style of their output, the level of advertising expenses and other selling activ-

ities, the level of research and development expenditures, their financial policies, their

investment decisions and so on.

A theory of the firm must have a minimum degree of generality so as to be applicable

to the explanation of the behaviour of a ‘group’ of firms rather than to the explanation of

the behaviour of a particular firm. Individual case studies are of interest to the particular

firms to which they refer, but several case studies are required before a theoretical model

of the behaviour of firms may be constructed.

We finally note that a model should be constructed in such a way so as to be testable,

that is, to be capable of being verified or refuted when confronted (compared) with the

true economic facts.

II. CLASSIFICAYION OF MARKETS

Various criteria have been suggested for the classification of markets. The basiccriteria

are the existence and closeness of substitutes (substitutability of products criterion) 2nd the

extent to which firms in the industry take into account the reactions of competitors

(interdependence criterion). The latter criterion is closely related to the number of firms

in the industry and the degree of differentiation of the product. If there are many firms

in the industry each one of them will tend to ignore its competitors and act atomistically.

Ifthere are few firms in the industry each one will be conscious of its interdependence with

the others and will take into account their reactions. Bain? has suggested a third criterion

for market classification, namely the ‘condition of entry’ which measures the ‘ease of

entry’ in the various markets (see below).

; See P. Samuelson, Foundations of Economic Analysis (Harvard University Press, 1947).

? See J. S. Bain, ‘Chamberlin’s Impact on Microeconomic Theory’, in R. E. Kuenne (ed.),

Studies in Impact of Monopolistic Competi i 5 repri i

I ipetition Theory (Wiley, 1967); reprinted in H. Townsend

(ed.), Readings in Price Theory (Penguin, 1971). i °

v

jion

mene

sraditionally he folowing market structures ae distinguished

perfect competition

fect competition there is a very large number of

T of

Mis perfect in the sera the industry and the

sense that every firm considers

rm acts atomistically, that is, it decides it:

Bistry. The products of the firms are its level of o

price-elasticity of the demand curve of

easy:

utput ignoring the i

heated Substitutes for one oni as at the

\¢ individual firm is infinite, Entry is free and

Monopoly

Ina monopoly situation there is only one firm in the industi ‘close

substitutes for the product of the monopolist. The demand of es monealn ‘coincides

with the industry demand, which has a finite price elasticity. Entry is blockaded.

Monopolistic competition

In a market of monopolistic competition there is a very large number of firms, but

their product is somewhat differentiated. Hence the demand of the individual firm has

anegative slope, but its price elasticity is high due to the existence of the close substitutes

produced by the other firms in the industry. Despite the existence of close substitutes

each firm acts atomistically, ignoring the competitors’ reactions, because there are too

many of them and each one would be very little affected by the actions of any other

competitor. Thus each seller thinks that 1e would keep some of his customers if he raised

his price, and he could increase his sales, but not much, if he lowered his price: his de-

mand curve has ah’ 4 price elasticity, but is not perfectly elastic because of the attach-

ment of customers .o the slightly differer.tiated product he offers. Entry is free and easy

in the industry.

Oligopoly

In an oligopolistic market there is a small number of firms, so that sellers are con-

scious of their interdependence. Thus each firm must take into account the rivals’ re-

actions. The competition is not perfect, yet the rivalry among firms is high, unless they

make a collusive agreement. The products that the oligopolists produce may be ae

geneous (pure oligopoly) or differentiated (differentiated oligopoly). In the latter cased

elasticity of the individual market demand is ‘smaller than in the case of the homogeneous

‘ > at the rivals’ reactions (as well as at the consumers’

laopety Ti eles ae tan ry and the time lag which they fore~

reactions), Their decisions depend on the ease of entry A00 He \g which they fo

i i tion and the rivals’ reactions. Given that there is a

cast to intervene between their own ac’ A ier of Rms may

F f aa

very large number of possible reactions of competitors, th avi fir

assume various forms. Thus there are various models of oligopolistic behaviour, each

based on different reaction patterns of rivals. |

From the above trict description of the characteristics of the various aed we may

present a scheme of market classification using the following measures for the degree

product substitutability, sellers’ interdependence and ease of entry.

6 ‘Basic Tools of y

The degree of substitutability of products may be measured Mehy, i

price ross-elastcty(e, for the commodities produced by any Two eg ogy

ae by

. eis] + ak “* dp dy *

& This measures the degree to which the sales of the jth firm are affected 2

price charged by the ith firm in the industry. If this elasticity is high, the prnsTE*® itty”;

hth and the ith firms are close substitutes. If the substitutability of products sof the

is perfect (homogeneous products) the price cross-elasticity between Rae aoe) :

ducers approaches infinity, irrespective of the number of sellers in the macyes | Pr

products are differentiated but can be substituted for one another the itt Ht the

tlasticity will be finite and positive (will have a value between zero and infect, os

products are not substitutes their price cross-elasticity will tend to zero. ‘nfinity Mthe

The degree of interdependence of firms may be measured by an u

quantity cross-elasticity for the products of any two firms? ;nconventionay

ap,

enn =

dq, P,

This measures the proportionate change in the price of jt in

infinitesimally small change in the atest produced oy the three from an

value of this elasticity is, the stronger the interdependence of the firms will ee

number of sellers in a market is very large, each one will tend to ignore the reacti e

competitors, irrespective of whether their products are close substitutes; in this cacti

quantity cross-elasticity between every pair of producers will tend to zer0. Ifthe number

of firms is small in a market (oligopoly), interdependence will be noticeable even whe

Pee are strongly differentiated; in this case the quantity cross-elasticity will be

inite.

For a monopolist both cross-elasticities will approach zero, since ex hypothesi there

are no other firms in the industry and there are no close substitutes for the product of the

monopolist.

The ease of entry may be measured by Bain’s concept of the ‘condition of entry’, which

is defined by the expression

where E = condition of entry

P, = price under pure competition

P, = price actually charged by firms.

The condition of entry is a measure of the amount by which the established firms inan

industry can raise their price above P, without attracting entry (see Chapter 13).

See R. L. Bishop, ‘Elasticities, Cross-Elasticities, and Market Relationships’, American

Economic Review (1952); comments by W. Fellner and E. Chamberlin and reply by Rishop

‘American Economic Review (1953) pp. 898-924; comment by R. Hieser and reply by Bishop,

“american Economic Review (1955) pp. 373-86. Also see R. L. Bishop, “Market Classification

Again’, Southern Economic Journa! (1961).

2 Alternatively, one might use the number of firms in a market as a measure of the degree of

interdependence. This measure, however, may be misleading when the number of firms is

large, but the market is dominated by one (or a few) large seller(s). Under these conditions

interdependence would ‘obviously be strong despite the large number of firms in the industry.

wr. yassification which

Ket Of emerges

ff on shows in table 1.1. from the applica 7

oo ipo noted that the dividing lines be

i A oul rent arbitrary. However, markets Shoulae sitterent

| ppg! PUPS assied

ee Table 11 Classicaton of marke!

i

Substitutability.

oforiuctertetn ttn taxowy

criterion

4a) P,

= ep y= SU 4

i) ah

a ;

competition a hk .

pureeticcom On. <0 x8 =

‘petition =o

re oligopoly +0 a

paseo oe fan < E>0

oligopoly lr <0 0

Monopoly” =o 0

entry

# For the monopolist the price and quantity cross-elasticiti

saher industries. cities refer to products and sellers in

1. THE CONCEPT OF AN ‘INDUSTRY’

Inthis book we will adopt the partial equilibrium approach. The basis of this approach

jsthe study of the industry. In this section we will attempt to define this concept and show

its usefulness in economic theory. '

A. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CONCEPT OF AN ‘INDUSTRY

The concept of an industry is important for economic analysis. It is also important to

the businessman, to the government, to those involved in the collection and processing,

of economic data, and to all research investigators. .

In economic analysis the concept of an industry js very important in the study of com-

petition. Firstly, it reduces the complex interrelationships of all firms of an economy to

oe dimensions. In a broad sense each firm is competing vio ea

economy. This might lead one to think that a general equi P A

the behaviour ofeach firm would be depicted by an‘ equaton(the WalsianPe as

nots appropriate for the study of the economie reality. However, the gener

ium has not as yet yielded a satisfactory frame ee

‘conomic units, Eee firms. The general equilibrium ad

2pplications (input-output analysis and aggregate Sea roacl

© deal with a different range of problems than the parti tre relevant Per the study

aggregate evonometric models (and the input-OUlPU! NT rato

and the prediction of aggregate magnitudes, such as total OWP

‘mployment, enter tc. B:

, consumption, investment, etc.

. . 7 mic . in RE, Kuenne (ot)

suudt’ J+ Bain, ‘Chamberlin’s Impact on Miron i 16; reps

in Impact of Monopolistic Competition The0 1

Townsend (ed.), Readings in Price Theory (Peng 197

wn

ag

. iction of the behavi

vp i for the study and the prediction o} ehaviour of ;

detailed informatio’ aang study of the behaviour of firms makes it n ae

dividual econom! s in order to gain some insight into ¢h,°

i tion of firm:

Seat ene Se The concept of an industry has been developed to include 4”

‘ i relationship with one another. Irrespective oj

firms which are in som (oe perderlines between the various groups, the fine i

criterion u re behaviourally interdependent. Secondly, the concept of the indusy,

ae sibt to derive a set of general rules frcra which we can predict the behavioy,

es Oral g members of the group that constitute the industry. Thirdly, the concep,

cena provides the framework for the analysis of the effects of entry on the

i the equilibrium price and output. ;

Sepa an VBeaed ble, if one had to work with data of the in.

ould be unmanagéal i t

dividual firms of all the economy simultaneously. Even Triffin, who argued in favour of

the abandonment of the concept of the industry as a tool of analysis, recognised its

importance for empirical research. He argued that the concept is useful in concrete

empirical investigations after the industry's ‘content’ has been empirically determined to

i of the research. |

so ae businessmen act with the consciousness of belonging to an industry, which they

perceive as comprising those firms more closely linked with them. All decisions are

taken under some assumptions about probable reactions of those firms which the

businessman thinks will be influenced in some way by his actions. The businessman

perceives that the industry comprises the firms which will be affected by his decisions

and hence will react in one way or another.

Published data are grouped on the basis of standard industrial classifications. The

grouping is based on some criteria which may change over time. The compatibility of the

data of different sources which publish data ‘by industry’ is one of the main concerns of

any empirical investigator.

The government policy is designed with regard to ‘industries’. Government measures

aim in general at the regulation of the activity and performance of industries rather than

of individual firms.

B. CRITERIA FOR THE CLASSIFICATION OF FIRMS INTO INDUSTRIES

Two criteria are commonly used for the definition of an industry, the product being

produced (market criterion), and the methods of production (technological criterion).

According to the first criterion firms are grouped in an industry if their products are

close substitutes. According to the second criterion firms are grouped in an industry on

the basis of similarity of processes and/or of raw materials being used.

Which classification is more meaningful depends on the market structure and on the

purpose for which the classification is chosen. For example, if the government wants to

impose excise taxes on some industries the most meaningful classification of firms would

be the one based on the product they produce. If, on the other hand, the government

wants to restrict the imports of some raw material (e.g. leather), the classification of

firms according to similarity of processes might be more relevant.

Market criterion: similarity of products

Using this criterion we include in an industry those firms whose products are suffici-

ently similar so as to be close substitutes in the eyes of the buyer. The degree of similarity

* See R. Triffin, Monopolistic Competition and ilibris i.

ee eae alate General Equilibrium Theory (Harvard Uni:

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- (/IJJ A: Gi.&co1sDocument1 page(/IJJ A: Gi.&co1sMuhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- 2022 - 10 - 11 3 - 58 PM Office LensDocument4 pages2022 - 10 - 11 3 - 58 PM Office LensMuhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- p7kODWO16XIOXUXE 452Document64 pagesp7kODWO16XIOXUXE 452Muhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- DocScanner 10-Jul-2021 10.50Document2 pagesDocScanner 10-Jul-2021 10.50Muhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- 10-10-2022 Final Date Sheet Phase-IiiDocument1 page10-10-2022 Final Date Sheet Phase-IiiMuhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- The Protection Against Harassment of Women at The Workplace Act 2010Document15 pagesThe Protection Against Harassment of Women at The Workplace Act 2010Muhammad NomanNo ratings yet