Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Macroeconomics EC2065 CHAPTER 6 - MONEY AND MONETARY POLICY

Uploaded by

kaylaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Macroeconomics EC2065 CHAPTER 6 - MONEY AND MONETARY POLICY

Uploaded by

kaylaCopyright:

Available Formats

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

CHAPTER 6: MONEY AND MONETARY POLICY

Learning outcome:

By the end of the chapter, you will be able to address the following questions:

• Why has the link between money supply growth and inflation been unstable?

• What advantages do governments derive from being able to create money?

• What are hyperinflations and why are they so damaging?

• How should central banks conduct monetary policy?

• Is it better to have a monetary system without physical cash?

• Can and should nominal interest rates ever be negative?

• How do cryptocurrencies differ from existing forms of money?

Essential readings:

Williamson, Chapters 12 and 18.

Introduction:

Up to this point, our study of macroeconomics has focused only on real variables. In ignoring

any reference to money, we have implicitly assumed individuals do not suffer ‘money

illusion’ and that they are able to make decisions solely with reference to real values and

relative prices. But are there reasons why money matters that are missing from our earlier

analysis? In other words, why is money important for the functioning of markets?

1. Why Does Money Matter?

• There are three reasons why money matters and they are:

1. Money is used as a means of payment. Trade between individuals and firms in the

economy depends on having an object such as money that serves as a medium of

exchange.

2. Money matters is due to ‘nominal rigidity’. Some market prices are quoted in units of

money and slow to adjust, or are set in contracts that are renegotiated only

infrequently.

3. Changes in the value of money affect the willingness of individuals to hold money.

• The reasons that money matters in an economy are closely related to the three

functions of money: medium of exchange; unit of account; and store of value.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 1

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Money functions as a medium of exchange because money is accepted as payment

for goods and services. Direct barter exchange of different goods, or of labour for

goods, is inconvenient and difficult.

• Money functions as a unit of account as it is convenient to quote prices in terms of

money instead of relative prices among a huge range of different goods. Money is

also the conventional unit of account used to specify wages in employment contracts

and repayments in debt contracts.

• Money functions as a store of value as money is an asset that can be used to transfer

purchasing power over time. However, all assets act as stores of value, so this

function is not particular to money.

• We will focus on the two special functions of money, medium of exchange and

unit of account, with most of this chapter devoted to money as a medium of

exchange.

Medium of Exchange:

• The medium of exchange function of money arises from the problem of the absence

of a double coincidence of wants.

• A double coincidence of wants occurs when both person A and person B have a good

that the other person wants. In a specialised economy producing a vast range of goods

and services, a double coincidence of wants is rare.

• For trade to take place in markets, it must be in interests of both parties. Since double

coincidences of wants are hard to find, barter exchange is difficult.

• Exchange is made easier if one party is willing to accept money because then trade

requires only a single coincidence of wants where person A wants a good person B has

but person B does not want any good that person A has.

Unit of Account:

• The unit of account function of money results from there being too many relative

prices to quote directly among all the different goods and factors of production in an

economy.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 2

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• It is convenient to express all prices as amounts of money. Similarly, in contracts

written to govern long-term employment and creditor-debtor relations, it is

convenient to specify payments in terms of a conventional unit of account.

Different Objects That Serve As Money:

• The common forms of money in use today are notes and coins issued by

governments or central banks that do not have intrinsic value, i.e. they are not

valued for the material from which they are made. This type of money is known as

‘fiat’ currency.

• The other type of money commonly in use today is deposits at commercial banks.

These deposits are claims to fiat currency, so this a type of ‘credit’ money.

Commercial banks themselves hold fiat money as vault cash or reserves at the

central bank, which is another form of fiat money.

• There are also some new or experimental forms of money that are yet not in general

use but may become more widespread in the next decade. These include

cryptocurrencies, which are a private and decentralised system of money (without

central bank intervention).

• Central banks also have plans to set up central-bank digital currencies, which are a

centralised system of accounts where individuals hold money directly at a central

bank.

• Historically, money took other forms that are now extremely rare. These include

commodity money, where coins are made from precious metals, or notes issued by

the government were redeemable for precious metals on demand. There were also

private bank notes, a form of credit money, which were claims to commodity money.

2. A Search Theory Perspective On Money:

• To understand the medium of exchange function of money, the assumption was that

everyone can buy or sell in markets subject only to a budget constraint. The

sequence of transactions was irrelevant – all that mattered was that each person’s

overall budget constraint was satisfied.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 3

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• However, unless there is a double coincidence of wants for all trade, this implicitly

assumed a very high degree of coordination, or that short-term credit is freely

available and works without any friction. The reason is that a budget constraint

allows for purchases in a period even though people may not have yet received

payment for what they plan to sell.

• An alternative approach is known as ‘search’ theory. In a search model, all trade is

decentralised and occurs in meetings between pairs of individuals rather than in

centralised markets.

A Simple Search Model of Money:

• The idea of the search theory can be illustrated using a simple model with three

types of individuals. Think of these individuals as having different occupations, so

that they specialise in producing different goods.

• Moreover, individuals have different needs and tastes, so their preferences are not

the same. We assume no double coincidences of wants to highlight the usefulness of

money.

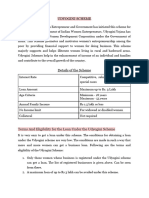

• A specific example of the three individuals is given in the figure below:

• In a search model there are no competitive, centralised markets. All trade must be

bilateral, meaning that it takes place between pairs of individuals. To keep the

analysis simple, assume only one indivisible unit of each of the goods and services

can be produced. This avoids the need to discuss prices at this stage because any

trade that takes place must involve one unit of goods being purchased or sold.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 4

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• In the absence of any double coincidence of wants, no trade can take place between

any pairs of individuals. However, this is inefficient. If all three individuals could meet

and coordinate a three-way exchange centrally then all three could have their wants

met by one of the others.

• In the example above, everyone produces a service, which cannot be stored. Once

we allow for physical goods, it is possible that one or more such goods can become a

commodity money.

• A commodity money has intrinsic value because of what it is made of, so it would

have a value even if it were not used as money. But, crucially, a commodity money is

accepted for payments even by those who do not want to consume the commodity

itself. Examples of commodity money are gold, silver and precious metals.

• The figure below modifies the earlier example so that one person can produce a

physical good and one person wants to consume that good. However, there is still no

double coincidence of wants for direct barter exchange. But all trade is possible if

everyone accepts the physical good in exchange for what they produce even if they

do not want to consume it. This enables the physical good to serve as a commodity

money.

• For a good to serve as a commodity money, it should be:

1. Easily storable at low cost, potentially for long periods of time

2. Easily transportable

3. Straightforward to verify the quality of the good

4. Easily divisible, for when exchange is not one-for-one.

In the above example, cake is assumed to be the commodity money.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 5

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• In the past, precious metals were a common form of commodity money, which

satisfy the first two of these requirements well. The use of coinage and convertible

notes or tokens added extra convenience, helping to satisfy the third and fourth

requirements.

• The advantage of a system of commodity money is that the limited supply and

intrinsic value of the commodity should give confidence that money will be a good

store of value, or at least not too bad.

• The disadvantage of a system of commodity money is that the system ties up

valuable goods as money, which either cannot be used directly, or there must be

extra production of the commodity, which has a cost. (However, gold actually have

other uses. Gold can also be used as jewellery directly by people)

Credit Money:

• An alternative to a system of commodity money is to use credit money.

• Credit money is where privately issued IOUs circulate as money. An IOU is a debt i.e.

a promise to deliver a payment in the future.

• The intended purpose of an IOU is a simple credit instrument, where, say, person A

offers an IOU to person B in exchange for something, which is accepted. Person A

then later redeems the IOU, giving person B what is owed.

• But IOUs could in principle become money if the initial holder uses it to make a

payment to someone else and then that person might pass it on to someone else as

well. Consequently, the IOU is held by a third party at redemption.

• An example of IOU is the government bonds where households can use government

bonds as collaterals when they borrow from commercial banks.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 6

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The figure below returns to the example with three individuals who produce only

services. Since services must usually be consumed at the point they are produced,

this rules out the use of commodity money. However, if everyone is willing to accept

someone’s IOU, that IOU can circulate as money. Through the use of this credit

money, all three individuals are able to purchase the services they desire.

Money And Credit:

• The example of a private IOU circulating as money shows that there is often a

connection between money and credit. However, it would be a mistake to see

money and credit as the same thing.

• First, not all types of money are credit. For example, in the example with commodity

money, no-one owes anything to anyone else. As we will see, fiat money is also not a

debt that the government is obliged to repay.

• Second, far from all credit ever becomes money. Very few individuals are sufficiently

well known that their IOUs could circulate as money. To use an IOU as credit money,

everyone who would subsequently hold the IOU needs to know and trust the issuer,

in addition to the first person to accept the IOU, which is all that would be required if

the IOU were used as a simple credit instrument. Only in the smallest communities

are these requirements likely to be met for circulation of individuals’ own IOUs.

• Considering these difficulties, for credit to serve as money, the IOUs need to be

issued by large, well-known and trusted companies or organisations. In practice, this

means banks.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 7

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Historically, bank IOUs took the form of their own issue of banknotes, which were

promises to repay deposits of commodity money. In the modern world, bank IOUs

typically take the form of deposits, which are claims to fiat money.

• If banks have created IOUs that are accepted for payments then it is easy to see how

these can be used to facilitate exchange among the three individuals in the earlier

example. Thus, trade can take place using credit money issued by banks even if the

individuals in the economy cannot persuade others to use their own IOUs as money.

• A system of credit money has some important advantages:

1. It is efficient system with a low resource cost because it does not tie up goods with

intrinsic value to be used as money.

2. Even if bank IOUs are claims to commodity money, banks would not need to hold

100 per cent of deposits as vault cash with intrinsic value. Banks can loan deposits to

support long-term investment. Some of the return on these investments can be paid

to depositors as interest, making bank deposits a better store of value.

• The disadvantages of credit money are:

1. Default by banks on their IOUs may cause a collapse of confidence in the monetary

system. Bank runs and bank failure disrupt trade and trigger financial crises.

2. Defaults by banks may be due to losses made on their loans, or even caused by a bank

run itself. These problems also lead to pressure for bailouts from the government,

creating a problem of moral hazard (‘too big to fail’).

• Individuals’ own IOUs cannot circulate as money. However, it is possible that some

forms of credit can be substitutes for money in making payments, for example,

credit cards.

• An individual paying with a credit card does not need to hold money at the time of

making a purchase, hence, this payment method acts as a substitute for money.

Essentially, the financial intermediaries that issue credit cards endorse individuals’

IOUs so others can be assured these debts will be repaid. The ability to use credit in

this way reduces frictions in payment because there is less need to hold money. In

this case, credit card can been seen as a medium of exchange and not a means of

payment.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 8

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• However, such a system of credit-based payments has costs for financial

intermediaries coming from the need to track credit histories and collect debt

repayments.

Fiat Money:

• Another form of money in widespread use is fiat money. This is defined as

government-issued money of no intrinsic value.

• The term ‘fiat’ suggests this money has value by government decree but that is

misleading because ultimately the real value of fiat money is determined in markets.

• Fiat money is not credit money because it is not a claim to anything other than itself

– it is not redeemable as an IOU is. Historically, government-issued notes may have

been claims to commodity money but this is no longer the case.

• In accounting terms, fiat money is recorded as a liability of the government or

central bank but it is important to remember that is quite unlike private-sector

liabilities such as bonds or loans. ( Recall the Central Bank’s balance sheet)

• The physical form of fiat money is cash, comprising notes and coins of non-precious

metal.

• Commercial banks hold some fiat money as vault cash but in modern monetary

systems, the reserves of commercial banks are usually held in accounts at the central

bank.

• In this form, fiat money is only an entry in a database recording how much each

commercial bank has on ‘deposit’ in its reserve account at the central bank. While

currently households and firms do not hold reserves directly, commercial banks can

convert reserves and cash one-for-one.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 9

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The figure below shows how trade can take place using fiat money in the earlier

example with three individuals:

• Initially, someone holds a unit of fiat money and everyone accepts it for payments.

The fiat money circulates among the individuals and everyone can consume the

service they desire. Note that the fiat money remains in circulation after all the

exchanges have taken place. This implicitly assumes the fiat money will go on being

used for future trade.

• Fiat money shares the advantage of credit money in being an efficient, low-cost

system because the intrinsically worthless money that is used has a negligible

resource cost (there are still some costs of production for the notes and coins, and

costs of handling cash for the private sector). It is important that individuals can

easily recognise units of fiat money as genuine but this can be achieved to a

sufficient degree of accuracy with appropriate anti-forgery devices.

• The potential disadvantages of fiat monetary systems also stem from fiat money

lacking any intrinsic value. As currency has a much lower cost for the government to

produce it than its market value and, as there is no obligation to redeem it, there is a

temptation to issue more fiat currency to raise revenue. The abuse of this money-

issuing power by governments results in money being a poor store of value and, at

worst, hyperinflation.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 10

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Furthermore, because fiat money is not redeemable for anything other than itself,

its value depends on the belief that others will continue to accept it for payments.

Note that in the figure above, the fiat money is never withdrawn from circulation.

This means that those choosing to accept money must always believe that others

will continue to accept money in the future. In principle, such beliefs could be

subject to self-fulfilling shifts because the belief that others will not accept fiat

money justifies individuals choosing not to accept it.

• However, in practice, the concern about self-fulfilling losses of confidence in fiat

currency may be mitigated by the government’s power of taxation. Governments

can insist on payment of taxes in their own currencies, which ensures there is always

some demand for money. The payment of taxes in fiat money to the government

could also be seen as a mechanism through which fiat money is withdrawn from

circulation.

Box 6.1: Cryptocurrencies:

• Recent years have seen a rise to prominence of cryptocurrencies, most famously

Bitcoin, but now many others too. Cryptocurrencies are a type of privately created

money in an electronic form. The operation of cryptocurrencies is a decentralised

system, unlike the centralised control of fiat money by governments.

• Nonetheless, cryptocurrencies share some features of fiat money. They have no

intrinsic value, which makes them very different from commodity money.

Cryptocurrencies are also not IOUs in any sense, which means they are not credit

money.

• Proponents of cryptocurrencies have put forward several advantages namely:

1. The blockchain technology they build on makes transactions very secure.

2. Because the supply of a particular cryptocurrency is limited by design, it is argued

there is less risk of the cryptocurrency losing value due to oversupply – in contrast to

fiat money where governments have discretion to create more – making

cryptocurrencies a better store of value. However, limited supply is necessary but

not sufficient to preserve value, which also depends on a stable or growing demand

for a currency.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 11

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Critics of cryptocurrencies argue there are serious disadvantages namely:

1. The value of a cryptocurrency depends on others’ beliefs about its future value,

which risks significant volatility (in theory, this is also a drawback of fiat money).

Values of cryptocurrencies have indeed been extremely volatile, making them far

from a traditional risk-free asset.

2. As with cash, the anonymity allowed by cryptocurrencies may facilitate criminal

activity, although this anonymity might also be valuable in fostering civil liberties.

3. There is the cost of the computing power used to maintain the distributed ledger,

implying that cryptocurrencies may entail significant resource costs, a disadvantage

shared with commodity money.

How do cryptocurrencies fit into our analysis of money?

• We will usually think of money as an asset that serves as a medium of exchange but

which is less good compared to other assets as a store of value.

• But cryptocurrencies are currently little used as a traditional medium of exchange –

not many purchases of goods and services use cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrencies

have had high (although volatile) rates of return, unlike traditional forms of money.

• In light of these observations, it may be better to think of people holding

cryptocurrencies as a financial asset rather than as money in the usual sense of the

term. With no dividends and all returns coming from capital gains, one approach to

analysing cryptocurrencies is as ‘bubbles’ in the overlapping generations model.

3. Money and Assets As Stores of Value:

• Storing value is a function of money but this function is not unique to money. All

assets must act serve as stores of value to some extent and many often do this

better than money.

• For example, bonds may offer a real return 𝑟 from interest payments, shares pay

dividends, property earns rents and shares and property may benefit from capital

gains.

• Considering money, let 𝑖𝑚 denote the return on holding money for a period in terms

of units of money itself. For example, if money is interpreted as funds in a bank

account, 𝑖𝑚 is the interest rate paid on deposits.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 12

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• If money is cash for which no interest is paid then 𝑖𝑚 = 0. Note that 𝑖𝑚 is a nominal

interest rate and a nominal return: it is the percentage increase in the amount of

money held simply by holding on it for some amount of time.

• The terminology we will use throughout this chapter is that nominal refers to

something measured in units of money, while real refers to something measured in

units of goods.

If the nominal return on money is 𝒊𝒎 , what is the implied real return?

• The real return on money, and nominal assets more broadly, depends on the

inflation rate in the economy. (Think of the Fisher equation)

Inflation:

• Inflation is defined as a general rise in prices quoted in terms of money. Inflation

affects how good or bad money is as a real store of value.

• Let 𝑃 denote the price of this good, or basket of goods, in terms of units of money. If

the price level in the current period is 𝑃, the notation for the price level in the next

period is 𝑃′. The rate of inflation between these time periods is denoted by 𝜋:

𝑷′ − 𝑷

𝜫=

𝑷

Note that this definition of inflation refers to the percentage change in prices

between the current level and the level that will prevail in the future.

• It is also possible to measure inflation between the past and current periods and

where that inflation rate is relevant, the notation will be adjusted to accommodate

it. Note also that the future price level 𝑃′ and the resulting inflation rate are not

known in current period. Where the distinction between and expected inflation is

important, the notation 𝛱 𝑒 will be used to denote expected inflation.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 13

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• In the following figure, it shows data on inflation for the USA in the post-war period:

• Observing from the figure above, inflation is volatile at the end of the 1940s but

becomes very low and stable in the 1950s. The 1960s see an increase in the inflation

rate, which reaches double digits in the 1970s. Inflation is brought under control in

the 1980s and remains stable throughout the 1990s. This stability continues into the

2000s except for the years around the 2007–8 financial crisis and its aftermath.

• To calculate the real change in spending power when holding money, the value of

money, plus any interest 𝑖𝑚 that accrues, is adjusted for changes in the money prices

of goods and services. Take the amount of money 𝑃 that currently buys one unit of

goods. If held simply as money then this becomes (1+𝑖𝑚 )𝑃 units of money in the

future period and with a price level P’, it would be possible to buy (1+𝑖𝑚 )𝑃/𝑃′ units

of goods in the future.

• The definition of the real return 𝑟𝑚 on money is that holding an amount of money

sufficient to purchase a unit of goods now yields purchasing power over 1+ 𝑟𝑚 units

of future goods. The percentage real return on money 𝑟𝑚 is therefore calculated

from the equation:

(1 + 𝑖𝑚 )𝑃 1 + 𝑖𝑚 1 + 𝑖𝑚

1 + 𝑟𝑚 = = ′ =

𝑃′ 𝑃⁄ 1+𝜋

𝑃

1+𝑖𝑚

Hence, 1 + 𝑟𝑚 = 1+𝜋

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 14

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Observe that (1+ 𝑟𝑚 )(1+𝜋) = 1 + 𝑖𝑚 implies 1+ 𝑟𝑚 + 𝜋+ 𝑟𝑚 𝜋= 1 + 𝑖𝑚 . If 𝑟𝑚 𝜋 is small

compared to 𝑟𝑚 and 𝜋, the real return on money is approximately given by 𝑟𝑚 ≈ 𝑖𝑚

− 𝜋. In the case where no interest is paid on money (𝑖𝑚 =0), for example, when

money is interpreted as cash, then the real return is approximately 𝑟𝑚 ≈ −𝜋. This

says that the inflation rate is approximately the percentage loss of purchasing power

of money over time.

The Fisher Equation:

• The equivalent calculation of the real return on holding nominal bonds is known as

the Fisher equation. A nominal bond is one that specifies payments in terms of units

of money. It is natural for bonds to make payments in this form following on from

our earlier discussion of money’s role as a unit of account.

• Suppose that a nominal bond makes a single payment of interest in terms of money

in the next period and this payment is certain. The interest rate specified by the

bond is 𝑖, the nominal interest rate and nominal return on holding the bond. This is

known when the bond is purchased. The substantive assumption here is that the

bond payment is not indexed to inflation.

• The Fisher equation gives the implied real return, referred to as the real interest rate

𝑟:

(1 + 𝑖)𝑃 1+𝑖

1+𝑟 = ′

=

𝑃 1+𝛱

The justification for this equation is that one unit of goods costs 𝑃 units of money in

the current period. If this money is used to buy bonds that offer a nominal interest

rate 𝑖, the amount of money returned when the bond matures in the next period is

(1+𝑖)𝑃. Dividing this by the future price level 𝑃′ gives the amount of future goods

that can be purchased. The equation then follows by noting that 𝑟 is defined so that

buying nominal bonds worth a unit of goods today gives the ability to buy 1+𝑟 units

of goods in the future.

• Rearranging the equation gives 𝑖= 𝑟+𝜋 +𝑟𝜋, so if 𝑟 and 𝜋 are small, the term 𝑟𝜋 is

negligible compared to the other terms, and it follows that 𝑟≈ 𝑖− 𝜋. This equation,

which can also be written as 𝑖 ≈ 𝑟+ 𝜋, is the approximate version of the Fisher

equation.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 15

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The Fisher equation states that the real return on bonds is the difference between

the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. This is an approximation, and in

contexts where the inflation rate can be very high, the exact version 1+𝑖 =(1+𝑟)(1+𝜋)

will be used.

Ex-Ante and Ex- Post Interest Rates:

• Inflation affects the real return on nominal assets such as money and nominal bonds.

However, inflation 𝜋 as defined earlier is the percentage change in the price level

between the current and future time periods, which is therefore not known in

advance. This means the Fisher equation can be used with either actual inflation 𝜋 or

expected inflation 𝜋 𝑒 as appropriate.

• Using the expected inflation rate 𝜋 𝑒 leads to an expected (ex-ante) real interest rate

𝑟 𝑒 ≈ 𝑖− 𝜋 𝑒 , or by giving this equation in its exact form, 1+ 𝑟 𝑒 =(1+𝑖)/(1+ 𝜋 𝑒 ). Using the

actual inflation leads to the actual (ex-post) real interest rate 𝑟 ≈ 𝑖− 𝜋, or in its exact

form, 1+𝑟 = (1+𝑖)/(1+𝜋).

• Different from nominal bonds, inflation-indexed bonds have the same actual and

expected real returns. This type of bond is sometimes referred to as a real bond to

distinguish it from bonds that specify payments in terms of fixed amounts of money

The opportunity cost of holding money:

• Money provides an important service in facilitating transactions as a medium of

exchange. Despite this advantage, money generally performs less well as a store of

value than other assets.

• To the extent that the return on holding money is below the return on alternative

assets, there is an opportunity cost of holding money that must be set against its

benefits in facilitating transactions. This opportunity cost is inversely related to how

well money performs as a store of value.

• We will take nominal bonds as the alternative asset to which money is compared.

The nominal interest rate on bonds is 𝑖, which is also the nominal return on holding

bonds. If money pays interest at nominal rate 𝑖𝑚 then the relative return on bonds

compared to money is the difference between the interest rates 𝑖− 𝑖𝑚 . Note that this

relative return is the same if calculated as a comparison of real returns 𝑟 and 𝑟𝑚

because the same inflation rate 𝜋 is subtracted from both:

𝒓 − 𝒓𝒎 = (𝒊 − 𝜫) − (𝒊𝒎 − 𝜫) = 𝒊 − 𝒊𝒎

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 16

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The opportunity cost of holding money is therefore 𝑖𝑖−𝑖𝑖𝑚𝑚. As we will see, the

opportunity cost is usually positive, with holders of money forgoing a generally

higher return on bonds.

• If no interest is paid on money (𝑖𝑚 =0), for example where money is physical cash,

then the opportunity cost is simply 𝑖𝑖. In this case, the level of nominal interest rates

on bonds is a measure of the opportunity cost of holding money.

Real And Nominal Interest Rates:

• In the earlier analyses of consumption, saving, and investment in Chapter 3 shows

that it is the (expected) real interest rate 𝑟 that is important for incentives. For

example, the theory of investment links the real interest rate to the marginal

product of capital net of depreciation.

• We have seen there are reasons to believe that real interest rates should be positive

on average if the productivity of capital is sufficiently high, or households are

impatient. But theory does not rule out times when real interest rates are negative.

• A time series of US real interest rates is shown in the figure below:

• From the figure above, this shows that real interest rates are positive but low on

average (around 2 per cent). The 1980s featured much higher real interest rates,

which peaked at close to 10 per cent. Real interest rates were positive but lower in

the 1960s and the 1990s. There are also times of negative real interest rates in the

late 1940s, 1970s and, more recently, from the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis

through to 2021.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 17

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The nominal interest rate also matters independently of the level of real interest

rates. This is because it affects the relative returns on money and bonds in a world

where at least some forms of money pay no interest, which influences how

households allocate wealth between different assets.

• Empirically, US nominal interest rates have almost always been positive, though

there have been long spells where they have been close to zero, most notably after

the 2008 financial crisis. On average, nominal interest rates are higher than real

interest rates, reflecting the positive average rate of inflation. The broad pattern for

US nominal interest rates is that they were very low in the 1940s, increased over the

subsequent decades to peak close to 15 per cent in the early 1980s and then

declined in through to the time of writing (2021).

• Nominal interest rates are clearly positive on average, indicating a positive

opportunity cost of holding money, particularly cash. In some countries, nominal

interest rates have occasionally turned negative.

4. The Demand for Money:

• The basic trade-off is that money facilitates economic activity by acting as a medium

of exchange but may not be so good as a store of value compared to alternative

assets.

• So, while money is useful to households and firms, they have incentives to

economise on holding money, use alternatives to money, or carry out fewer

transactions.

• Suppose that real GDP 𝑌 is an indicator of the number of transactions taking place in

an economy and each transaction requires using a means of payment such as

money. Here, we take the level of real GDP 𝑌 as given, returning later to the

question of whether that is affected by money and monetary policy. If the price level

is 𝑃, the money value of all transactions in the economy is 𝑃𝑌.

• To represent the role of money as a medium of exchange, we impose the following

transaction constraint in addition to the budget constraints faced by agents in the

economy:

M ≥ P(Y-X)

• This constraint specifies a minimum level of money that households and firms must hold

to carry out transactions.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 18

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Mathematically, it requires that the level of money holdings on average during a

period is sufficient to pay for transactions of real value 𝑌−𝑋, which correspond to an

amount of money 𝑃(𝑌−𝑋). The variable 𝑋 has several possible interpretations,

including efforts to economise on holding money or use alternatives to money in

carrying out transactions.

• Assume that money pays no interest. Holding money balances 𝑀 on average during

a period means forgoing interest 𝑖 that could have been earned from holding bonds

instead. If money pays interest at rate 𝑖𝑚 , all we need to do is replace the

opportunity cost 𝑖 with 𝑖− 𝑖𝑚 throughout this chapter.

• Taking as given 𝑃 and 𝑌, the minimum amount of money holdings consistent with

the transaction constraint can only be reduced and thus forgone interest saved, by

increasing 𝑋. As we now discuss, increasing 𝑋 has costs that we can compare to

forgone interest to derive households’ and firms’ demand for money.

Economising On Holding Money:

• The first interpretation of 𝑋 is efforts to economise on the amount of money held on

average. All 𝑃Y transactions are carried out with money but agents make frequent

exchanges between bonds and money to keep their average holdings of money

lower. Consequently, as 𝑋 rises, average holdings of money 𝑀 fall further below 𝑃Y.

• The benefit of higher 𝑋 is a reduction in forgone interest but this uses up time or

incurs transaction costs. These costs in real terms are specified by the function 𝑍(𝑋),

which is increasing in 𝑋. We assume 𝑍(𝑋) has the properties 𝑍(0)=0, 𝑍′(𝑋)>0, and

𝑍′′(𝑋)>0, the third of these implying that the marginal cost 𝑍′(𝑋) is increasing in 𝑋.

• Conditional on 𝑋, the lowest money holdings can be is 𝑀=𝑃(𝑌−𝑋). An increase of 𝑋

by 1 reduces the need to hold real money balances 𝑀/𝑃 by 1, which reduces the real

value of forgone interest 𝑖M/𝑃 on money holdings by 𝑖. The marginal benefit of

higher 𝑋 is thus equal to 𝑖. The marginal cost of higher 𝑋 is Z’(𝑋), which we will

denote by 𝑞 in what follows. The optimal choice of 𝑋* is where the marginal benefit

equals the marginal cost:

i = Z’(X*)

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 19

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The marginal cost function 𝑍′(𝑋) is shown as an upward-sloping line in the graph below

with 𝑋 on the horizontal axis and the marginal cost 𝑞 on the vertical axis:

• The optimal value of 𝑋* for a particular nominal interest rate 𝑖 is derived by drawing

a horizontal line at 𝑞=𝑖 and finding where it intersects the marginal cost function.

The figure shows that a higher nominal interest rate 𝑖 leads to an increase in the

optimal 𝑋*. Intuitively, if money is a worse store of value, meaning that the

opportunity cost 𝑖 is higher, it is rational to make more efforts to avoid holding it.

• Having derived 𝑋*, agents’ demand for money 𝑀𝑑 is the minimum amount allowed

by the transaction constraint (assuming 𝑖>0, so there is a positive opportunity cost):

𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃[𝑌 − 𝑋 ∗ (𝑖)]

This a money demand function of the form 𝑀𝑑 =𝑃L(𝑌, 𝑖), where real money demand

𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖)=𝑌−𝑋 ∗ (𝑖) is increasing in 𝑌 and decreasing in 𝑖.

• The choice of how much money to hold is related to the following measure of the

velocity of money 𝑉, which is defined by 𝑀𝑉=𝑃Y. This is a measure of how fast a unit

of money circulates in a given period as it is used for multiple transactions. Since

𝑉=𝑃Y/𝑀𝑑 =𝑌/[𝑌 − 𝑋 ∗ (𝑖)], velocity is inversely related to 𝑀𝑑 and increases with the

opportunity cost 𝑖 of holding money. Intuitively, money circulates faster with people

holding it for shorter periods when money is a poor store of value.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 20

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

Alternatives To Money:

• A second interpretation of 𝑋 in the transaction constraint 𝑀+𝑃X ≥𝑃Y is using

alternatives to money as a means of payment.

• In the earlier part of the chapter, we have also discussed how credit might be used

as a substitute for money in some situations. Suppose banks offer credit facilities, for

example, credit cards and let 𝑋 now denote the real value of transactions paid for

with credit. Think of this as short-term credit, with borrowing during a period repaid

at the end of the period. A fee 𝑞 is charged for using credit as a fraction of the

amount borrowed.

• In offering credit, banks face costs of screening borrowers and collection of debts.

Assume that these costs are an increasing function 𝑍(𝑋) of 𝑋. In addition, the

marginal cost Z’(𝑋) of extending provision of credit is increasing in the amount of

borrowing 𝑋. This represents the idea that banks would face higher costs when they

expand lending to a wider group of less credit-worthy borrowers, or extend more

credit to existing borrowers.

• Assuming the banking system is competitive, banks offer credit 𝑋 𝑠 up to the point

where the fee charged 𝑞 is equal to the marginal cost 𝑍′(𝑋):

q= Z’(𝑋 𝑠 )

This yields an upward sloping supply curve 𝑋 𝑠 (q) for credit facilities.

• Consider the demand for credit by households and firms as a means of payment.

Transactions can equally well be carried out using credit facilities or using money.

The credit facility fee is 𝑞 per unit of spending is the cost of using credit for

payments. If money is used instead then the cost is the opportunity cost 𝑖 of holding

money.

• Since the two means of payment are perfect substitutes, if 𝑞 < 𝑖 then payment with

credit facilities is preferred, if 𝑞 > 𝑖 then payment using money holdings is preferred,

and if 𝑞= 𝑖 then everyone is indifferent between the two. It follows that the demand

for credit facilities 𝑋 𝑑 (𝑞) is perfectly elastic in the range 0≤ 𝑋≤ 𝑌 with respect to the

fee at 𝑞= 𝑖.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 21

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The demand function 𝑋 𝑑 (𝑞) is plotted alongside the supply function 𝑋 𝑠 (q) in the

diagram below:

• The demand curve shifts vertically if the nominal interest rate 𝑖 changes, moving

upwards if 𝑖 rises. The equilibrium of the market for credit facilities is at the

intersection of the demand and supply curves. Assuming 𝑋 ∗ < 𝑌, so some amount of

money is held to make payments, the equilibrium features 𝑞*= 𝑖, so the credit fee is

equal to the nominal interest rate on bonds.

• An increase in 𝑖 shifts the demand function upwards, so the equilibrium 𝑋 ∗ (𝑖) rises

with 𝑖. As it does not make sense to hold more money than required to satisfy the

transaction constraint when 𝑖 >0, the money demand function is 𝑀𝑑 =

𝑃[𝑌 − 𝑋 ∗ (𝑖)], which has the same form as seen earlier with the first interpretation

of 𝑋.

The Money Demand Function:

• Considering 𝑋 as either effort to economise on holding money, or substitution

towards alternatives to money, the resulting money demand function has the form:

𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖)

• The function 𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖)=𝑌−𝑋 ∗ (𝑖) for holdings of real money balances 𝑀𝑑 /𝑃 increases in 𝑌

and decreases in 𝑖. Nominal money demand 𝑀𝑑 is proportional to the price level 𝑃 for

given real transactions and interest rates because higher prices scale up the need for

units of money to make payments.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 22

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Money demand 𝑀𝑑 increases with 𝑌 as higher GDP means more transactions. Money

demand 𝑀𝑑 decreases with 𝑖 because a higher opportunity cost increases incentives to

reduce money holdings through various means.

• The money demand function is plotted against the price level 𝑃 in the left panel of the

diagram below for given values of real GDP 𝑌 and the nominal interest rate 𝑖:

• It is an upward-sloping straight line because nominal money demand is proportional

to the price level. The demand function pivots to the right if 𝑌 increases or 𝑖 falls.

• The relationship between the nominal interest rate 𝑖 and real money demand 𝑀𝑑 /𝑃

is depicted in the right panel of the diagram above. The negative relationship reflects

the incentive to reduce money holdings when the opportunity cost 𝑖 is high.

Mathematically, the demand curve represents the optimality condition 𝑖= 𝑍′(𝑋),

where 𝑋= 𝑌−(𝑀/𝑃) using the binding transaction constraint.

• The demand curve shifts to the right if 𝑌 increases. In the special case 𝑖= 0, there is

no forgone interest when holding money and the optimal value of 𝑋 is 0. Moreover,

there is no incentive to reduce money holdings until the transaction constraint just

holds. Hence, with a zero nominal interest rate, money demand is 𝑀𝑑 ≥𝑃L(𝑌, 0)=𝑃Y,

which corresponds to a horizontal line at 𝑖= 0. Money demand thus becomes

perfectly interest elastic at 𝑖=0.

• Finally, we note that when money itself pays interest at rate 𝑖𝑚 , all references to 𝑖

above in the money demand function should be replaced by the correct opportunity

cost 𝑖−𝑖𝑚 .

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 23

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

5. Money and Economic Activity:

• In our study of money demand revealed the ways in which it is affected by real GDP

and interest rates. But does money itself matter for real GDP?

• The analysis here will focus on money’s medium of exchange function, which

affects the efficiency with which markets operate. Later in Chapter 8, money’s unit

of account function becomes relevant in the presence of nominal rigidities.

• In this chapter, we look at the implications of economic activity depending on

holding money for some period between selling one thing and buying another.

Money that is a poor store of value over this period acts as a tax on economic

activity, therefore discouraging production and exchange.

• This idea can be illustrated using the labour market as an example. Suppose the

period is a month and workers are paid a wage 𝑊 per hour of labour only at the end

of the month. Wages arrive too late to be spent directly during the same month, and

suppose it is not possible for workers to barter labour for goods, or offer IOUs for

payment when they buy goods.

• Households’ labour supply condition 𝑀𝑅𝑆1,𝐶 = 𝑤 derived in Chapter 1 assumed an

extra hour of labour paid money wage 𝑊 buys 𝑤= 𝑊/𝑃 goods in the same period.

But to work more and spend more during the same month in the monetary economy

described above, a household must either forgo interest by holding on to more cash

at the beginning of the month, swap money and other assets more frequently during

the month at some cost, or pay for goods using credit as an alternative to money. All

of these ways of spending more during the month before actually receiving the wage

at the end of the month entail some cost.

• We derive the amount of goods 𝑤𝑚 that can be purchased in the same month when

a household supplies an additional hour of labour paid money wage 𝑊, holding

constant the household’s future plans for consumption and labour supply.

• The effective real purchasing power of a household’s wages during the month is 𝑤𝑚 ,

which will generally differ from the real cost 𝑤 = 𝑊/𝑃 to firms when wages are paid

at the end of the month.

• Real purchases 𝑤𝑚 cost 𝑃𝑤𝑚 units of money. If the household holds extra money 𝑃𝑤𝑚

instead of bonds during the month to make the purchases then this reduces nominal

wealth by (1+𝑖)𝑃𝑤𝑚 at beginning of next month.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 24

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• To leave future spending plans unchanged, this needs to be replenished with the extra

wages 𝑊 received at the end of the month, hence, (1+𝑖)𝑃𝑤𝑚 = 𝑊. Dividing both sides

by 𝑃 implies that 𝑤𝑚 is related to 𝑤 as follows:

𝑤

𝑤𝑚 =

1+𝑖

This equation says that the effective purchasing power of the wages households

receive is reduced by 𝑖 because spending more requires holding more money, which

forgoes interest.

• Alternatively, the household could maintain the same average money holdings

during the month and avoid forgoing interest. However, this requires swapping

between money and other assets more frequently (higher 𝑋) during the month to

cover the additional spending. But this entails transaction costs 𝑞= 𝑍′(𝑋) per unit of

extra spending. Deducting these from the wage received implies 𝑃𝑤𝑚 = 𝑊−𝑞 𝑃𝑤𝑚 . It

follows that 𝑤𝑚 =𝑤/(1+𝑞).

• Finally, credit could be used for the extra purchases made during the month. This

requires paying a fee 𝑞𝑃𝑤𝑚 at the end of month. Deducting that from the wage

implies 𝑃𝑤𝑚 = 𝑊−𝑞 𝑃𝑤𝑚 and hence, 𝑤𝑚 = 𝑤/(1+𝑞). In point 4 earlier on, we saw that

households’ optimal choice of money holdings implies 𝑞= Z’(𝑋)= 𝑖, so this means that

𝑤𝑚 = 𝑤/(1+𝑖) whichever way of paying for current consumption that households

choose.

• Households’ labour supply decision in a monetary economy with the timing

restriction on receiving and spending wages equates the marginal rate of

substitution 𝑀𝑅𝑆1,𝐶 between leisure and current consumption to the effective

current purchasing power of the wage 𝑤𝑚 :

𝑤

𝑀𝑅𝑆1,𝐶 =

1+𝑖

The right-hand side of the equation is lower when the opportunity cost 𝑖 rises,

indicating that money is worse as a store of value. Since working and consuming

more depends on holding money for some time, a positive opportunity cost 𝑖𝑖 works

in a way similar to a proportional tax 𝜏 on wages. A proportional income tax on

wages means the households’ labour supply is determined by 𝑀𝑅𝑆1,𝐶 = (1−𝜏)𝑤.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 25

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• This logic points to one way that money matters for real GDP. If money is worse as a

store of value (a high opportunity cost 𝑖) then the implicit tax on economic activity

rises. This leads to a lower labour supply, shifting the 𝑁 𝑠 curve to the left. All else

equal, there is less employment and lower production, which causes a shift of the 𝑌 𝑠

curve to the left. Households are worse off, which reduces consumption demand and

shifts the 𝑌 𝑑 curve to the left as well. Consequently, real GDP 𝑌 is lower. If 𝑌 𝑠 and

𝑌 𝑑 shift by the same amount, then the real interest rate remains unchanged.

The Supply of Money:

• First consider the supply of fiat money by a government or central bank, deferring

discussion of ‘credit money’ created by the banking system until Chapter 7.

• Assume all money is fiat money, for which the government is the monopoly supplier.

The quantity of money in circulation is denoted by 𝑀 𝑠 . For now, we make no

distinction between cash and reserves.

How does the central bank change the money supply? In other words, how does new

money enter circulation or existing money is removed from circulation?

• There are two basic ways this can happen:

1. Open-market operations

2. Transfers.

Since fiat money is intrinsically worthless, the resource costs of creating new money

are negligible and we ignore them in our analysis.

Open Market Operations (OMO):

• An open-market operation is where the central bank buys or sells assets.

• When the central bank buys assets, it pays with newly created money, which

increases the quantity of money in circulation. When the central bank sells assets, it

receives existing money as payment, which is effectively removed from circulation.

(Think about the balance sheet of the Central Bank)

• The central bank can in principle buy any asset in an open market operation or sell

any asset it already holds. It usually transacts with the private sector through its

dealings with commercial banks (rather than buying bonds directly from the

government).

• Traditionally, open-market operations were in markets for short-term government

bonds, or repos (repurchase/resale agreements) of long-term government bonds.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 26

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• These assets were chosen because they have low credit risk and a short maturity and

thus protect the central bank from capital losses that would make it harder to

reverse an expansionary open-market operation in the future. But since the 2008

financial crisis, many central banks have also made outright purchases of long-term

bonds or risky assets, for example, quantitative easing (QE) purchases of mortgage-

backed securities in the US.

Transfers:

• A transfer payment is where the central bank distributes money without acquiring

any asset in return, for example, the payment of central-bank profits to a country’s

finance ministry.

• These profits often arise as a normal outcome of the central bank’s operations and

are distributed to the finance ministry as the owner of the central bank.

• However, in principle – putting aside legal rules – a central bank can create new

money and simply distribute it to the finance ministry or others. This could mean

directly paying for government expenditure, or giving the government money to

compensate for lower tax revenues.

• The case of a direct payment of new money to households is known as a ‘helicopter

drop’ of money, though the same economic effect could be achieved by a transfer to

the government to fund a tax cut for households.

Monetary Policy:

• The decisions the central bank makes that affect the supply of money are described

as its monetary policy. For now, we assume monetary policy is an exogenous supply

of money 𝑴𝒔 . This can be represented as a perfectly inelastic money supply curve

(vertical 𝑴𝒔 𝒄𝒖𝒓𝒗𝒆). This supply curve shifts if monetary policy changes.

• We will consider later what monetary policy should be chosen to meet the

objectives of a country’s government.

7. Money and Prices:

• This section combines the demand and supply of money to see how the level of

prices, the inflation rate and the nominal interest rate are determined.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 27

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Here, we suppose that goods prices in terms of money are fully flexible. This means

that the real value of money adjusts to be equal to the real amount of money that

households and firms are willing to hold. In Chapter 8 we consider how an economy

functions differently if there are nominal rigidities, for example ‘sticky prices’.

• With flexible prices, the price level 𝑃 adjusts to ensure the money market clears. The

nominal money supply 𝑀 𝑠 is assumed to be an exogenous amount 𝑀 chosen by the

central bank.

• Rather than consider a completely general monetary policy, we will restrict attention

here to monetary policies where the money supply is expected to grow at some

exogenous rate 𝜇 over time:

𝑴′ = (𝟏 + 𝝁)𝑴

The money demand function is 𝑀𝑑 =𝑃L(Y, 𝑖), and money-market equilibrium 𝑀𝑑 =

𝑀 𝑠 therefore requires 𝑀=𝑃L(𝑌, 𝑖) in the current period and M’ =P’L(𝑌 ′ ,𝑖’) in the

future.

• Nominal and real interest rates are linked by the Fisher equation 𝑖= 𝑟+ 𝜋, where the

inflation rate is defined by 𝜋= (𝑃’−𝑃)/𝑃. The conditions for equilibrium in the money

market now and in the future are therefore 𝑀=𝑃L(𝑌, 𝑟+𝜋) and 𝑀′ =

𝑃′ 𝐿(𝑌 ′ , 𝑟 ′ + 𝛱 ′ ). A graphical representation of the current period equilibrium is

shown in the diagram below where the equilibrium price level 𝑃* is at the

intersection of 𝑀𝑑 and 𝑀 𝑠 .

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 28

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• By dividing the future money-market equilibrium condition by the current money-

market equilibrium condition we obtain the equation:

𝑀′ 𝑃′ 𝐿(𝑌 ′ , 𝑟 ′ + 𝛱 ′ )

=

𝑀 𝑃𝐿(𝑌, 𝑟 + 𝛱)

We suppose that the types of monetary policies considered here do not affect future

real GDP 𝑌′ differently from how they affect current real GDP 𝑌 (that is, they do not

change the future real GDP growth rate), or the current real interest rate 𝑟 relative

to its future level 𝑟′, or 𝜋 relative to 𝜋′. All else being equal, this means 𝑌= 𝑌′, 𝑟= 𝑟′,

and 𝜋= 𝜋′. Note we have not ruled out that monetary policy affects the levels of 𝑌, 𝑟,

or 𝜋.

• The equation for money-market equilibrium then reduces to 𝑀′/𝑀 =𝑃′/𝑃. With

definitions 𝑀′/𝑀= 1+ 𝜇 and 𝑃′/𝑃 =1+ 𝜋, money-market equilibrium therefore

implies:

𝜋=𝜇

The rate of inflation 𝜋 is equal to the money-supply growth rate 𝜇, which means that

inflation is determined by monetary policy through the choice of 𝜇.

• Intuitively, increases in the money supply shift the 𝑀 𝑠 curve to the right, which imply

that the intersection with 𝑀𝑑 occurs at a higher price level 𝑃 to leave holdings of

real money balances unchanged. And this can be graphically shown as follow:

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 29

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Given a real interest rate 𝑟, the Fisher equation implies: 𝑖 = 𝑟+ 𝜇 since 𝜋 = 𝜇.

A higher money-supply growth rate thus raises the nominal interest rate 𝑖 if 𝑟

remains unchanged. This is because a higher nominal interest rate is required to

cancel out the effect of inflation and leave the real return on bonds the same.

Box 6.2: The Instability of Money Demand:

• The analysis of the equilibrium inflation rate might give the impression that only the

money supply growth rate matters, a form of ‘monetarism’. This is because we have

considered only shifts of the money supply curve for a completely stable money

demand curve.

• However, the equilibrium of the money market can also be affected by shifts of the

money demand function and this affects the equilibrium price level for a given

supply of money. If such demand shifts occur then this leads to fluctuations in

inflation even if monetary policy keeps the money supply or money growth constant.

𝑀𝑑

• The money demand curve 𝑃

= 𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖) can shift because of changes in real GDP 𝑌,

which affect the need to use money for transactions. But in addition to this, the function

𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖) itself might not be stable owing to financial innovation.

• New ideas or technologies can change the costs of providing substitutes for money, for

example, credit cards, or change the costs of economising on the average amount of

money held to carry out transactions, for example, ATMs, debit cards and electronic

payments.

• We can represent the effects of these innovations in the model by shifts of the

marginal cost function 𝑍′(𝑋). Since the money demand is determined by the

𝑀𝑑

equation 𝑖=𝑍′(𝑌− ), these changes also shift the money demand function as shown

𝑃

in the diagram below:

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 30

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Reduction in the marginal cost of providing substitutes for money or economising on

money holdings increases 𝑋 and reduces money demand, causing the price level to

increase for a given money supply 𝑀 𝑠 .

How serious an issue is the instability of money demand?

• The left panel of the diagram below reports a time series of the quantity of money

𝑀 𝑠 in the USA relative to nominal GDP 𝑃Y. Note that this uses the M1 measure of

the money supply, which is broader than the monetary base and that we study

further in Chapter 7. The measure 𝑀 𝑠 /(𝑃Y) is the inverse of the velocity of money

𝑉=(𝑃Y)/𝑀. In equilibrium, it is also equal to (𝑀𝑑 /𝑃)/𝑌, which is real money demand

relative to real GDP 𝑌. The scaling by GDP is done to control for changes in the

demand for money owing to transactions rising with GDP.

• We see that M1 as a fraction of GDP followed a stable trend prior to the 1980s but

has experienced various shifts in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. The right panel of the

figure is a scatterplot of 𝑀 𝑠 /(𝑃Y) against the nominal interest rate 𝑖, which should

show the downward-sloping real money demand curve scaled by GDP. However, the

plot indicates this relationship has been unstable.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 31

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The exercise is repeated for the broader M2 measure of the US money supply in the

figure below:

• The time series in the left panel suggests the demand for M2 (relative to GDP) has

been more stable than M1. The scatterplot in the right panel comes closer to tracing

out something that resembles a negative relationship between real money demand

(scaled by GDP) and the nominal interest rate 𝑖, though this relationship still appears

to shift at some points in time.

• Overall, the evidence presented here suggests we cannot be confident that

regulating the money-supply growth rate will give tight control over inflation.

8. Money and Public Finance:

• Governments derive a fiscal advantage from being able to issue fiat money that is

demanded by the private sector. Unlike bonds, there is no obligation to ‘repay’ or

redeem fiat money.

• Furthermore, money may pay no interest (𝑖𝑚 = 0), or pay a lower rate of interest than

bonds (𝑖𝑚 < 𝑖). These fiscal gains from issuing money are often referred to as the

‘seigniorage’ revenue of the government. They represent an implicit tax on holders

of money.

• This section looks at how to quantify the fiscal gains that arise from different

monetary policies.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 32

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

Seigniorage: ‘Printing Money’

• If the money supply is growing at a rate 𝜇 then an amount of new money 𝜇M is

created each time. If it were directly used to finance government expenditure, this

seigniorage revenue would be worth 𝜇M/𝑃 in real terms. Using 𝜋 = 𝜇 that results

from money-market equilibrium, the real amount of seigniorage is 𝜋M/𝑃.

• This is simplest and most direct measure of seigniorage as the fiscal advantage that

comes from ‘printing money’. But this calculation ignores the saving of regular

interest payments on past spending that has been financed in this way rather than

by issuing bonds.

• Moreover, most central banks are not in the business of directly financing

government expenditure. What if – the usual case – the central bank is buying assets

with newly created money?

Seigniorage: Central Bank Investment Income

• Assume money pays no interest and all money created by the central bank has been

used to buy nominal bonds. The central bank holds bonds of monetary value 𝑀 that

matches exactly the existing supply of money 𝑀.

• In this case, the central bank earns interest 𝑖M in each period and, ignoring resource

costs of creating money and any operating costs, these are profits that can be paid

out to the finance ministry.

• Real seigniorage revenues are 𝑖M/𝑃, which represents a flow of revenue received by

the government in each period. Note that this is different from the seigniorage

measure based on the real value of the increase in the money supply.

A General Definition of Seigniorage:

• Even if the central bank does not buy assets, the central-bank investment income

definition of seigniorage still accurately represents the fiscal advantage derived from

steady growth in the money supply.

• The government reduces the cost of financing public expenditure by creating money

rather than issuing interest-bearing bonds. The size of this advantage can be

calculated as the real quantity of money 𝑀/𝑃 in circulation multiplied by the

difference in the returns on bonds and money, which is the nominal interest rate 𝑖

when money does not pay interest.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 33

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Seigniorage then simply represents money being less good as a store of value than

bonds, which is an advantage from the perspective of the issuer of money.

• With 𝑖= 𝑟+ 𝜋, and 𝜋 = 𝜇 in equilibrium with a constant money-supply growth rate 𝜇,

the central-bank profits definition of seigniorage can be broken down into:

𝒊𝑴 𝒓𝑴 𝜫𝑴 𝒓𝑴 𝝁𝑴

= + = +

𝑷 𝑷 𝑷 𝒑 𝒑

This is the saving of real interest payments on bonds otherwise issued plus the

erosion of existing money’s real value due to new money being created.

Limits on Real Seigniorage Revenues:

• As seigniorage arises from money being less good a store of value than other assets,

it is an implicit tax on money. Seigniorage is closely related to the notion of forgone

interest we saw in the analysis of money demand and is essentially identical to the

total amount of forgone interest on money.

• If money becomes a worse store of value because the nominal interest rate 𝑖 is

𝑀𝑑

higher then real money demand = 𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖) falls. Real seigniorage revenues are

𝑃

𝑖M/𝑃=𝑖 L(Y, 𝑖), so there are two conflicting effects of higher 𝑖:

1. The direct effect of money being worse as a store of value.

2. The indirect effect of falling real money demand reducing the real value of

seigniorage.

This means the relationship between real seigniorage revenues and 𝑖 is not

unambiguously positive. Observe that seigniorage is zero if 𝑖=0 and becomes zero

again for high 𝑖 if real money demand 𝐿(𝑌, 𝑖) falls towards zero sufficiently fast as 𝑖

increases. This gives rise to a Laffer curve for real seigniorage revenues as shown in

the figure below, indicating there are limits on the amount of real seigniorage

government can obtain.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 34

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

The Inflation Tax:

• If there is an unpredictable increase in the inflation rate 𝜋, the nominal interest rate

𝑖 on bonds cannot rise to leave the real return 𝑟 unchanged.

• An inflation surprise thus reduces both the real value of nominal government bonds

as well as existing money. This is reflected in the ex-post real interest rate 𝑟 being

less than the ex-ante real interest rate 𝑟 𝑒 .

• The fiscal advantage derived from such surprise inflation is referred to here as an

‘inflation tax’. A different term is used because the mechanism through which the

inflation tax works is distinct from the source of seigniorage revenue discussed

earlier.

• With the definitions adopted here, seigniorage revenues derive only from money not

bonds and do not depend on inflation being a surprise. In contrast, the inflation tax

depends on inflation that was unexpected when nominal bonds were first issued.

This means that, ex post, the inflation tax does not have any incentive effects on

behaviour – like a lump-sum tax – because it is completely unexpected.

• There is no inflation tax on the real value of nominal bonds when the inflation is

anticipated. In this case, the real return is protected from expected inflation when

the nominal interest rate 𝑖 adjusts in advance.

• Inflation-indexed bonds are also protected against surprise inflation and offer a

guaranteed real return.

The Government Budget Constraint and Ricardian Equivalence:

• In spite of the fiscal advantage that governments can derive from issuing money – a

form of ‘soft default’ on government debt – a government ‘budget constraint’ still

holds once seigniorage and the inflation tax are counted alongside other more

conventional sources of tax revenue.

• Moreover, seigniorage and the inflation tax also show up in households’ budget

constraints alongside explicit taxes because of they bear the losses from forgone

interest and the erosion of the real value of nominal bonds by surprise inflation.

• If the economy has a representative household, it is possible to combine the

household and government budget constraints in the way seen in Chapter 4. The

present value of government expenditure ultimately determines the present value of

tax revenue from all sources, including seigniorage and the inflation tax.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 35

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• However, Ricardian equivalence fails because seigniorage is effectively a tax that

distorts incentives.

9. Does Monetary Policy Matter?

Monetary policy should affect nominal prices and inflation but what effects are there, if

any, on real variables such as GDP?

• We can answer this question in the context of a model where the special feature of

money is its role as a medium of exchange. Money matters in different ways, in

particular, through its unit of account function, in the models with nominal rigidities

we will see from Chapter 8.

• We will consider two different changes to monetary policy:

1. A permanent change in the quantity of money in circulation

2. A permanent change in the growth rate of the supply of money in circulation.

A Permanent Change in The Level of The Money Supply:

• Suppose there is an exogenous permanent change in money supply 𝑀 𝑠 = 𝑀. Since

this is exogenous, it is not a reaction to other events or shocks. We assume the

change is unexpected and that no repeat is expected in the future. This means the

level of 𝑀 changes but not its subsequent growth rate 𝜇.

• As the future money supply 𝑀′ changes in the same way as the current money

supply 𝑀, a zero money-supply growth rate 𝜇=0 is expected subsequently because

𝑀′ = 𝑀. However, when the policy change is implemented, there is still an

unexpected change in the money supply 𝑀 relative to its past level.

• Since the change in the money supply is the same in the present as in the future, the

effects on the equilibrium price levels 𝑃 and 𝑃′ are the same. This means that

expected inflation 𝜋=(𝑃′−𝑃)/𝑃 between now and the future period is 𝜋= 𝜇= 0. From

the Fisher equation we therefore conclude that 𝑖= 𝑟+ 𝜋= 𝑟. Although there is no

further inflation expected in the future, there can still be unexpected

inflation/deflation of 𝑃 relative to the past price level.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 36

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• Consider the case of an increase in the money supply 𝑀 for illustration. We will see that

the model predicts this increase in 𝑀 has no real effects at all. This result is shown in the

supply-and-demand diagrams for the goods, labour and money markets depicted in the

figure below. But what is the logic for this striking claim?

• First, and most importantly, prices and wages expressed in units of money are fully

flexible here. With no impediments to price adjustment, the same real wage 𝑤 and

real interest rate 𝑟 can continue to ensure supply and demand are brought into

equilibrium in the labour and goods markets. Moreover, there is no money illusion –

everyone’s decisions depend on relative prices and real variables.

• Second, the policy change does not affect perceptions of how good money is as a

store of value going forwards between the current and future time periods. Since 𝑖=

𝑟, there is no change in the nominal interest rate 𝑖 unless 𝑟 changes. The nominal

interest rate 𝑖 is a measure of how bad money is as a store of value relative to other

assets. This means no greater tax on economic activity that depends on holding

money is expected and, hence, there is no reason for the labour and output supply

𝑤

curves to shift through the effect of 𝑖 on the labour-supply condition 𝑀𝑅𝑆𝑙,𝐶 = 1+𝑖.

• Third, while existing holdings of money and nominal government bonds are caught

by a surprise inflation tax that reduces the real value of households’ financial assets,

the inflation tax also allows the government to reduce other taxes and still pay for

the same level of public expenditure. These tax cuts offset the reduction in the value

of financial assets and there is no wealth effect overall on households – Ricardian

equivalence holds after accounting for the government budget constraint.

• Thus, we conclude there are no reasons for any shifts of the 𝑁 𝑑 , 𝑁 𝑠 , 𝑌 𝑑 , or 𝑌 𝑠

curves. Therefore, the equilibrium values of 𝑤*, 𝑟*, 𝑁*, and 𝑌* are unaffected.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 37

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• A permanent change in the money supply has no real effects. No change in 𝑌 or 𝑖

means there is no shift of the money demand curve 𝑀𝑑 . The rightward shift of the

money supply curve 𝑀 𝑠 thus leads 𝑃 to rise in proportion to 𝑀. Given these

predictions, money is said to be ‘neutral’.

A Permanent Change in The Growth Rate of The Money Supply:

• Alternatively, suppose there is a permanent adjustment of the growth rate of the

money supply 𝜇. This money-supply growth rate is defined by 𝜇=(𝑀′−𝑀)/𝑀, hence,

the future money supply is given by 𝑀′=(1+𝜇)𝑀. The change in 𝜇 is exogenous,

unexpected and no further adjustments of 𝜇 are expected. Note that there is no

change in the initial money supply 𝑀 here.

• Since the policy change affects expectations of the future money supply, inflation

expectations 𝜋=(𝑃’−𝑃)/𝑃 adjust. The effect on the equilibrium current and future

price levels 𝑃 and 𝑃’ is such that 𝜋= 𝜇, so any changes in money-supply growth are

reflected one-for-one in changes in expected inflation.

• Consider the case of faster money growth for illustration. We will see that increasing

the money growth rate does have real effects. These are depicted in the supply-and-

demand diagrams below:

• The logic for the real effects is that higher money growth 𝜇 raises expectations of

future inflation 𝜋. The Fisher equation 𝑖= 𝑟+ 𝜋 then implies the nominal interest rate

𝑖 is higher for each value of the real interest rate 𝑟. From the labour-supply equation

𝑤

𝑀𝑅𝑆𝑙,𝐶 = 1+𝑖 , higher 𝑖 has a negative effect on labour supply.

• Intuitively, because money is a worse store of value, the implicit tax on economic

activity rises, which causes the supply of labour to decline. Consequently, the output

supply curve 𝑌 𝑠 shifts to the left and, as this change is permanent, 𝐶 𝑑 falls in line

with income, leading to a leftward shift of 𝑌 𝑑 of same size as the shift of 𝑌 𝑠 .

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 38

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• If a permanent change in the money supply growth were to have no effects on any

real variables then we would say that money is ‘superneutral’.

• The term ‘neutrality’ used earlier refers to there being no real effects of a permanent

change to the level of 𝑀. We see in the diagrams above that the model predicts

money is not superneutral.

• Permanently faster growth of the money supply reduces real GDP and employment

because money is less good as a store of value. This inflationary policy has a negative

real effect on the economy’s supply side.

• In the money market, there is no initial change in 𝑀, so no shift of the money supply

curve 𝑀 𝑠 to begin with. The money demand curve 𝑀𝑑 pivots to the left as there are

fewer transactions due to lower GDP 𝑌 and more efforts to economise on holding

money or make use of money substitutes (higher 𝑋) because of higher 𝑖. This leads

real money balances 𝑀/𝑃 to fall as 𝑀𝑑 /𝑃 is lower, which causes an immediate jump

up in the level of prices 𝑃.

Box 6.3: Money Supply Increases That The Central Bank Announces Are Temporary

• We have looked at the consequences for prices, inflation and real economic

variables of permanent changes to the quantity of money or the growth rate of the

money supply. But central banks might change the money supply temporarily in

some circumstances.

• For example, quantitative easing (QE) might increase the money supply but it is the

central bank’s stated intention to unwind the policy in the future. QE expansions of

money supply have turned out to be persistent in most countries, although this may

not have been expected when they were first begun.

• There are cases where QE has been temporary, such as the Bank of Japan QE policy

from 2001, which was largely reversed in 2006. Another example of a temporary

change is the ‘de-monetization’ experiment in India in 2016, where there was a

temporary decline of the money supply.

• To see what difference it makes when a money-supply change is expected to be

temporary, suppose 𝑀 𝑠 = 𝑀 is expected to change for only one time period.

Throughout, we hold the expected future money supply 𝑀′ constant. Consequently, the

equilibrium future price level 𝑃′ does not change in this example.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 39

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• The Fisher equation 𝑖= 𝑟+ 𝜋 and the definition of expected inflation 𝜋=(𝑃′−𝑃)/𝑃

imply that the nominal interest rate 𝑖 is:

𝑃′ − 𝑃 𝑃′

𝑖=𝑟+ =𝑟+ −1

𝑃 𝑃

• Money-market equilibrium is the equation 𝑀= 𝑀 𝑠 = 𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃L(𝑌, 𝑖), and, hence:

𝑃′

𝑀 = 𝑃𝐿 (𝑌, 𝑟 + − 1)

𝑃

• The key point to note is that a higher price level 𝑃 lowers the nominal interest rate 𝑖

here, so the effect of 𝑃 on money demand is magnified. We ignore here any effect of

𝑖 on 𝑌 (but accounting for that would further boost the impact of 𝑃 on 𝑀𝑑 ).

• In what follows, we assume that nominal interest rate 𝑖 remains positive throughout.

The diagram below depicts the relationship between 𝑀𝑑 and 𝑃 in this case for given

𝑌 and 𝑟 and the relationship in the case where changes in the money supply are

permanent, in which case money demand 𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃L(𝑌, 𝑟) is proportional to 𝑃 and is

thus represented by a straight line in the diagram.

• Following temporary increase in 𝑀, the money supply curve 𝑀 𝑠 shifts to the right as

usual. If the policy is expected to be reversed in future, any rise in the price level is

also expected to be reversed. Therefore, a higher price level 𝑃 would create

expectations of future deflation, reducing the nominal interest rate 𝑖 and boosting

money demand.

PREPARED BY CHEN AIDI 40

EC2065 MACROECONOMICS

• In the diagram, 𝑀𝑑 is thus less steep than the usual 𝑃L(Y, 𝑟) money-demand

function. It follows that the price level rises by proportionately less than 𝑀 does, in

contrast to the case of a permanent change where 𝑃 rises in proportion to 𝑀.

• This different prediction compared to the case of a permanent change in 𝑀 is likely

to be quantitatively significant. If there were a 25 per cent higher money supply

temporarily and 𝑃 went up by 25 per cent initially then this would require 25 per