Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 2 Architecture of The First Emperor and His Predecessors 2019

Uploaded by

Lajos OrosziOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 2 Architecture of The First Emperor and His Predecessors 2019

Uploaded by

Lajos OrosziCopyright:

Available Formats

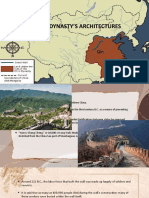

CHAPTER 2

Architecture of the First Emperor and His Predecessors

Upon the move of the capital to Luoyi (Luoyang), the Zhou period of Western Han.3 Wangcheng is to be a square whose

controlled less of China than they had for most of the previ- four wall positions are determined by measuring out from a

ous three hundred years. Instead, dozens of states rose, built midpoint according to the sun’s shadow. Each side of the wall

cities, and vied for power during the period known as Spring is 9 li, the number nine associated with fullness and perfection

and Autumn. Cast iron appeared in China around the eighth and, by extension, with royalty. Major thoroughfares are to

century BCE, making metal weaponry easier to produce and cross the entirety of Wangcheng from wall to opposite wall.

cheaper, in addition to the use of iron in agricultural imple- The central thoroughfares, however, are blocked by the ruler’s

ments.1 Bronze and jade technology became more sophisti- palace, positioned in its own walled enclosure. The palace faces

cated, with inscriptions on bronze vessels remaining an impor- south with markets behind it, a temple to the ruler’s ancestors

tant source of information about the major historical figures on the east, and altars to soil and the five grains on the west

of the period and their states. Writings of this Classical Age (figure 2.1).4 A civilization of archetypical images, ever aware

of Chinese thought provide information directly relevant to of and building on its past and at times resisting innovation,

architecture and ceremonies in and around it, and thousands Chinese imperial urbanism shows resonances of this idealized

of tombs offer information about building technology as well plan through the rest of China’s imperial history. Yet already in

as objects that filled them. the Eastern Zhou dynasty alternate arrangements of Chinese

rulers’ cities existed.

Rulers’ Cities A key feature prescribed for Wangcheng persists: the pal-

ace-city, or gongcheng. Indicated in Shang and earlier capitals,

Passages in texts of the early centuries CE have guided the a designated, walled palace area is found in almost every Zhou

understanding of architectural remains dated from the city where a ruler resided. The evidence is stronger in Eastern

Western Zhou through the early Spring and Autumn period Zhou than Western, for as mentioned above, once the Zhou

in the region of central Shaanxi known as Zhouyuan, the capital moved east, contenders for power increased, and with

area that once belonged to the state of Qin, discussed in the time, the sizes of cities of those who prevailed increased as well.

previous chapter. The phrase qian(you)chao, hou(you)qin, or “in The many Eastern Zhou cities divide into only four plans.

front, audience hall; behind, private (or resting) chambers,” a The city Wangcheng described in the “Kaogongji” is the

reference to the placement of buildings in imperial settings, Zhou capital Luoyi, which was squarish, about 3 kilometers on

is almost iconic:2 it was observed at Majiazhuang and is still each side, and surrounded by a moat. A few building founda-

in place in the Forbidden City, where the Three Front Halls tions have been excavated, but not enough remains to confirm

were for audience and other court functions and the Back that it followed the prescription for an ideal ruler’s city. Qufu,

Halls were for imperial residence; and when the empress held in Shandong province, where Confucius was born in 551 BCE,

audience in the Back Halls sector, she slept behind her hall and Anyi in Shanxi are the closest Eastern Zhou examples to

of audience. Her position behind the emperor was further the Wangcheng plan. The late Longshan city Guchengzhai,

demonstration of the greater importance of a front building mentioned in chapter 1, may have had this plan as well. Qufu,

or complex and lesser significance of architecture behind. The capital of the state of Lu from the reign of King Cheng in the

idea that the more public space of a ruler is in front of where eleventh century until conquest by the state of Chu in 249 BCE,

he lives and sleeps is in evidence at every Chinese imperial city was surrounded by a rectangular wall with rounded corners

from the third century onward and will be implemented in that measured about 3.7 kilometers east to west and 2.7 kilo-

tomb and cave-temple construction. meters north to south, all enclosed by a 30-meter-wide moat

One passage from “Kaogongji” (Record examining trades or (figure 2.2). The wall had eleven gates, two on the south side

crafts [including construction]), a section of the Zhouli (Rituals and three on each other face. Ten major thoroughfares ran

of Zhou), has emerged as preeminent in writing about Chinese through the city, five north-south and five east-west, each ema-

cities. It is a prescription for Wangcheng (ruler’s city). Like the nating from a city gate or leading to an important building.

rest of “Kaogongji,” the passage is believed to refer to Zhou Large building foundations in an area of about 1,000 by 500

practices, even though the text survives probably from the meters, roughly in the center of the outer wall, are believed

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 20 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

to be from an enclosed palace-city. Three foundations on an

axial line are believed to have supported a gate, palatial hall,

and altar. That area was inside the confines of the Han-period

city wall, which shared its southern and western border with

part of the Zhou city but was outside a later wall that survives

in part today.5 The Eastern Zhou city at Anyi in Xia county

of southwestern Shanxi had much in common with the Lu

capital in Shandong. Both were oriented northeast-southwest.

Measuring 4.5 kilometers north-to-south and 2.1 kilometers

east-to-west, Anyi’s palace area was roughly in the center of

a much larger outer city. The Anyi city was last studied in the

early 1960s, so we do not have the kind of information available

for the capital of the Lu state. In the 1960s Anyi went by the

name Yuwangcheng, city of King Yu, Yuwang also the name of

the village where it was found.6

The second urban pattern of the Eastern Zhou period is

represented by Jiang, the capital of the state of Jin in Shanxi

province. Here the roughly rectangular outer city wall was 8.48

kilometers in perimeter, surrounded by a moat. The 1-kilo-

meter-square inner city was in the north center, sharing a

boundary with the north outer wall. A street of more than a

kilometer in length ran from the north wall through the inner

city and into the outer city.7

The third urban pattern is the most common among capi-

tals of large Zhou states: multiple walls that are not concentric.

Adjacent walled enclosures positioned north and south, east

and west, or at the corners of each other are among them, and

occasionally there are more than two walls. The state of Zhao,

in Handan in southern Hebei, flourished from 403 to 222 BCE.

The 1.888-square-kilometer site has archaeological remains

from the period of Spring and Autumn. That area became

an outer city when the Zhao moved its capital to Handan in

386 and constructed adjacent east and west cities south of it. 2.1. Illustration of Wangcheng, “ruler’s city,” from Nie Chongyi, Sanlitu

In this case, then, there are three adjacent walls (figure 2.3a). (Illustrated “The three li (ritual) classics”), part 1, juan 4/26, orig. 962

In the palatial sector, the western enclosure is just under 1.4 2.2. Wall of Qufu, capital of state of Lu, Shandong, second half of first

meters on each side and contains the largest building plat- millennium BCE

form known from the later part of the Zhou dynasty. Almost

certainly the place identified in texts as Dragon Terrace, it north to south and approximately 1.4 kilometers east to west.

forms a roughly north-south line with two smaller building Only one foundation platform remains inside, suggesting it

platforms behind it. The eastern city to the south is 926 meters may have been the palatial area of the Spring and Autumn city.

east to west by 1.442 kilometers north to south. This wall is Another platform is directly opposite outside the northern

20–40 meters wide as opposed to 20–30 meters for the western city’s western wall, perhaps evidence that there was another

wall. Here, too, three platforms form an axial line through the enclosure of the earlier city. Workshops have been excavated

city north to south. The older, northern city is 1.52 kilometers outside the walls to the northwest.8 Handan is an example of

21

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 21 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Chapter 2

2.3. Plans of three multiwalled cities of the Eastern Zhou period

a. Handan, capital of Zhao, Hebei; b. Xiadu, capital of Yan, Hebei; c. Linzi,

capital of Qi, Shandong

a city where additional walls and growth continued when new by 110 meters and 11 meters high, is probably the foundation of

rulers conquered existing cities. Wuyang Terrace.9 Bronze, iron, bone, and pottery workshops

Xiadu, literally lower capital, of the Yan state in Yi county, are among the ruins of the eastern sector of Yan Xiadu, as are

Hebei, just south of Beijing, is an example of an Eastern Zhou places where bronze currency was cast. Cemeteries are found

city with adjacent walled areas that are further divided by a in both cities.10

canal (see figure 2.3b). Positioned between rivers to the north The capital of the state of Qi in Linzi, Shandong, which

and south, the 30-square-kilometer area stretched about 8 flourished for more than six hundred years from 859 to 221

kilometers east to west by between 4–6 kilometers north to BCE, is one of the oldest examples of a city with adjacent walls.

south. The more developed part of the Yan capital was on the Here the palace-city was in the southwestern corner of a much

east with an enclosed sector to its north. Remaining wall por- larger walled area (see figure 2.3c). The rammed-earth outer

tions are about 40 meters wide. A narrow sector at the north wall was 14 kilometers in perimeter and contained a popula-

is further divided from the rest of the eastern sector. Platform tion of 210,000 households. Two gates provided access on the

foundation remains suggest this northern area was the location north and south, and there was a single gate on the eastern and

of the palace. The number coincides with four terraces (tai) western sides. The seven main roads through the city emanated

named in Shuijingzhu (Commentary on the Waterways Classic), a primarily from city gates; they were as wide as 20 meters. The

treatise perhaps written in the third century and annotated in palace-city in the south, 1.5 by 2.5 kilometers, was enclosed by a

the early sixth century by Li Daoyuan (d. 527), which describes wall that at points was 60 meters wide. It, too, had main roads

137 waterways in China and, in the process, other features of passing through wall gates. A platform of 14 meters in height

the landscape such as cities. The central and largest terrace, 140 and 86 meters north to south known as Duke Huan Platform

22

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 22 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

was in the northeast. It was probably the main palace sector

through the city’s Zhou history. A drainage system ran beneath

both walled enclosures, and pottery, bronze, iron, and bone

workshops were found, as well as a mint. Two large cemeteries

also were excavated within the city. The cemetery of the later

rulers of Qi is about 10 kilometers outside the city walls.11

Xintian, capital of the state of Jin in Houma, southern 2.4. Reconstruction of section of sluice gate, south wall of Ying, capital of

Shanxi province, flourished from 585 to 376 BCE. It is better Chu state, Jiangling, Hubei, 689–278 BCE

evidence than Handan of continued occupation and growth

on a preexisting city site. By the end of the twentieth century, province, in 1972 contain sections of a document known as

seven walled enclosures, four of which shared space, had been Shifa (Rules about markets). According to Shifa, markets were

uncovered in an area that was 4.7 square kilometers. Large, administered by officials, specific products were sold in pre-

rammed-earthen foundations amid smaller ones were found scribed locations, and misconduct in the marketplace was pun-

in two of the enclosures, suggesting palatial halls. The capital ished.15 The text Zuozhuan (Zuo commentary) informs us that

of the state of Zheng, which became the capital of the state market officials were on duty in the pre–Warring States period

of Han in 375 BCE in Xinzheng, Henan province, was a city of Eastern Zhou. The third-century-BCE official Xunzi wrote

of about 20 square kilometers with two adjacent walls; its that in the earlier part of Eastern Zhou, market directors were

small palace area, only 500 by 320 meters in extent, was in the largely responsible for maintenance, cleaning, traffic flow,

western walled section. The eastern city was not significantly security, and price control, and in later Eastern Zhou they

larger than the western one, but it may have served as an outer expanded to merchandise inspection, settlement of disputes,

city. The Xinzheng capital had several bronze foundries and is loans, and tax collection for sales, property, and imported

the source of important bronze hoards that included musical goods.16 One also learns from texts that each state market

instruments.12 had its own name. Whether Eastern Zhou states functioned as

The fourth type of Eastern Zhou city had a single wall with city-states according to the definition used for those of ancient

a palace sector inside it. Ying, the capital of the state of Chu Greece is debated.17

just outside Ji’nan in Jiangling, Hubei province, today is an Archaeological evidence informs us about other aspects of

example. It was founded in 689. Contained in walls that were commerce in and among Warring States cities. Seals that name

as thick as 40 meters at the base and tapered to 10–14 meters, officials in charge of state-controlled minting of coins and

and 4.45 by 3.588 kilometers in perimeter, the north and south foundries for bronze weapons and vessels are almost invariably

city walls had sluice gates that have been theoretically recon- found in the vicinity of palaces, suggesting that these indus-

structed as shown in figure 2.4. Eighty-four palatial founda- tries were tightly controlled by the state ruler. Workshops for

tions and more than thirty cemeteries with more than eight goods such as farming tools and pottery usually were farther

hundred mounded tombs have been identified.13 from palaces, perhaps suggesting less government control of

Hundreds of states vied for power in the Spring and Autumn manufacturing, sales, or distribution. More than thirty thou-

period.14 No name could more aptly describe the 250 years that sand coins uncovered at Yan Xiadu suggest that currency was

followed than Warring States. By the mid-third century BCE, an important commodity. An early-fourth-century massacre

only seven survived. The above-mentioned Qi, Yan, Zhao, Han, in this city has led to the theory that the urban population

and Chu were among them. The others were Wei and Qin. increased dramatically and posed a challenge to royal control

The capitals of each of these states and the many of the first of the city’s goods and production, and that the mass murder

millennium BCE that did not endure until the third century was an assertion of power by the ruler to regain control of his

had markets. The “Kaogongji” passage about Wangcheng states state.18 Other archaeological evidence suggests that warfare

that a market was part of every ruler’s city. Several other texts was not only inter- and intracity but between Chinese states

of the period reinforce the role of commerce in later Zhou and nomads at China’s northern frontier. Gold objects made

cities. Bamboo slips excavated in a tomb in Linyi, Shandong almost certainly by northern nomadic populations have been

23

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 23 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 24 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

found in Warring States period tombs. Entwined animals are

prevalent among the gold, and interlace patterns and inlay,

all characteristic of the art of peoples including the Scythians

known as Animal Style, dominate Chinese bronze vessels of

the Warring States period.

2.6. Reconstruction of inner coffin, tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Leigudun,

Rulers’ Tombs Sui county, Hubei, ca. 433 BCE

Our knowledge of these vessels comes from tombs, most of also reveals three important features of Eastern Zhou archi-

them belonging to Eastern Zhou kings or princes. Royalty were tecture. First, the contents and purpose of the compartments

interred in lingyuan, royal funerary precincts, spacious grounds are differentiated: the main chamber contained the marquis’s

that included architecture of the ruler, family members, often and eight other coffins, the latter all female sacrificial burials,

those close to him in life such as officials, and sometimes as well as the coffin of a dog; a room with thirteen coffins

servants or slaves, as well as aboveground architecture for is on the opposite side of the main chamber; between them

sacrifices and additional land that kept the tomb area isolated and to the north were burial goods. Second are the plank

from a nearby city of the living. This practice would continue walls, which are used in other tombs of the period such as

through the Han dynasty. Nonnobles also had cemeteries, as did one excavated in Xinyang, Henan.20 Third are windows. We

lineages. The size and structure of the tomb, number of coffins, have seen doors that open outward in a bronze vessel of the

numbers and kinds of bronze vessels, and presence of objects early Zhou period (see figure 1.15). Doors are painted on the

such as instruments were prescribed in texts and determined outer of two lacquered wooden coffins of the marquis, and

by rank. More than a dozen royal tombs or cemeteries of the windows divided into four panes are painted on the inner

Warring States period have been excavated. Here we highlight sarcophagus (figure 2.6). The window might be compared to

those with important architectural features or objects that the representation of windows or other light sources in tombs

provide unique information about architecture. of ancient Egyptian royalty, symbolically providing a view to

Chu, the largest state during the Spring and Autumn and the world outside.

Warring States periods, has yielded more than five thousand One of the most important artifacts for the study of

tombs. The above-mentioned Chu capital city in Ji’nan, Hubei, Eastern Zhou architecture was excavated in a cemetery of the

had sluice gates (see figure 2.4), and in Baoshan and Jingzhou, Zhongshan kingdom in Pingshan county of Hebei province.

both in Hubei, and elsewhere, Chu built royal tombs (figure King Cuo (r. 327–313 BCE) and his wife and concubines were

2.5). The single approach ramp, stepped sides, and coffin pit buried beneath truncated pyramidal mounds, his being 100.5

at the center are simplified compared to tombs of the late by 90 meters at the base and 18 meters square at the top. A

Shang rulers in Anyang (see figure 1.11). The tomb of Marquis funerary hall was on top of the mound. Again we see continu-

Yi of Zeng, a name on objects in his tomb but perhaps a ation of a much earlier practice: a funerary temple was on top

man whose name was different in historical records, in Sui of the tomb of Lady Hao at the last Shang capital in Anyang.

county of Hubei, who died in 433 BCE, was divided into four Also following precedents from Yin are approach ramps to

compartments, each lined with wooden planks and each con- King Cuo’s subterranean chamber from the north and south,

nected to adjacent sections by tunnels.19 This pit tomb with with the primary burial in a pit at the center, similar to the

no approach ramp had space between rooms and between the structure of the Chu tomb at Baoshan as well (see figures 1.11,

burial and ground level that was sealed by charcoal and other 2.5). Horse and chariot pits, treasuries, sacrificial burials, and a

materials. Although this tomb is best known for the set of pit for a boat were all part of the universe created underground

sixty-five bronze bells weighing about two-and-a-half tons, it for King Cuo. Here, too, one readily draws comparisons with

ancient Egyptian practices that included the burial of boats

2.5. Two Chu tombs, Juliandun, Baoshan, vicinity of Ji’nan, Jingzhou, Hubei, that would have made passage through the dark, watery under-

period of Chu state world possible.

25

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 25 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Chapter 2

The object is a bronze plate of 94 by 48 centimeters and

about 1 centimeter in thickness. A plan of the burial precinct

is inlaid with gold. The representation of three-dimensional

space in two dimensions is extraordinary anywhere in the

world in the third century BCE, and the use of scale is more

amazing. Distinctions in line thickness suggest that different

kinds of lines had different meanings for builders. Breaks in

lines indicate gates. Inscribed notations are as extraordinary

as the plaque itself. Building sizes and distances between

buildings and walls are provided. They are given in chi, a

unit of measure similar in usage to the English word foot,

and whose specific length changes through Chinese history,

and in bu, paces, even more similar to foot. South is at the

top of the diagram, where it would be for most of the rest

of China’s premodern cartographic history. Archaeologists

have named the diagram zhaoyutu, image of the “omen” ter-

ritory, zhao, or omen, presumably a reference to the funerary

world (figure 2.7).21

Perhaps even more important than the scaled and labeled

plan is the forty-two-character directive on the plate that

there be two copies, one to be kept in the palace and this sec-

ond one to be buried with the ruler. The purpose was so that

future generations would know how to construct a tomb in

the manner of their ancestors, and by inference, the under-

standing that the patterns of antiquity were to be followed

or, more explicitly, that the intent of royal architecture was

to model itself after its past and to be continued in the same

manner in the future.

The tomb of Yun Chang, the king of Yue on Mount Yin,

Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, was part of a moat-surrounded

cemetery of approximately 85,000 square meters. It had an

underground chamber that was triangular in section. The

tomb, 46 by 14–19 meters at the base and 14 meters into the

surface of the mountain, was lined with wooden slabs and

sealed with charcoal in the manner of the tomb of Marquis Yi

of Zeng. The subterranean space, 34.8 meters long, 6.5 meters

2.7. Zhaoyutu (plan of the omen territory), 94 by 48 by 1 cm, ca. 313 BCE,

excavated in tomb of King Cuo of the Zhongshan kingdom, Pingshan, Hebei. wide, and 5.6 meters high, was divided into three rooms. Burial

Hebei Provincial Museum was inside a 6.5-meter-long tree trunk that had been cut in half

(figure 2.8).22

2.8. Tomb of Yun Chang, king of Yue state, Yinshan, Shaoxing, Zhejiang,

Hebei, ca. 500 BCE As for other tombs of the Warring States period, tombs

of the state of Jin are in southern Shanxi and seem to divide

2.9. Drawing of bronze pole showing balustrades, cantilever corner according to the lineage of the deceased; south-facing tombs of

brackets, and hipped-roof with bird and dragon ornaments at the top and

drawing of its four sides, excavated at Xiadu, capital of the Yan state, Hebei, the state of Wei in Hui county, Shanxi, have funerary temples

Warring States period on top of mounds; mounded tombs believed to belong to Zhao

26

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 26 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

2.10. Sectional drawing and reconstruction of

multilevel, pillar-supported structure incised on

bronze vessel, excavated in Zhaogu village, Hui

county, Henan, Warring States period

royalty are in the vicinity of Handan; the royal cemetery of Qi Zhaogu village, Huixian, Henan, is even more informative. The

is in the vicinity of Linzi; and the royal cemetery of Yan is near structure is supported on a high foundation, with two stories

Xiadu. Seventeen log coffins, some carved into the shapes of above it. Theoretically reconstructed as it appears in figure

boats, excavated in a pit tomb of 30 by 21 meters at the base in 2.10, this depiction combined with excavations of architecture

Chengdu, were part of a royal cemetery of the state of Shu.23 and literary descriptions are the basis for reconstructions of

Excavated objects of the Warring States period may inform architecture through the end of the first millennium BCE.24

us about architectural details of the period. A bronze pole

divided into three registers supports a one-bay-square roofed Architecture of China’s First Empire

structure (figure 2.9). Like bronze vessels of the Western Zhou

dynasty, it shows the use of balustrades (see figure 1.15). The Between 230 and 221 BCE, the remaining six warring states

five-ridge roof has a dragon on each side ridge and winged fell to Prince Zheng (259–210 BCE) of the state of Qin, who

creatures at the ends of the main ridge. Similar creatures join declared himself Shi Huangdi, Primordial August Thearch,

cantilevers to the undersides of the roof to help support it. and founded the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) in 221; he is often

Animals on roof ridges and cantilevered bracketing will be referred to as the First Emperor. Although his own dynasty

standard in Chinese construction through the nineteenth endured a mere fifteen years, building principles observed in

century. A building engraved on a bronze mirror excavated in Qin were much older and endured much longer. The rendering

27

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 27 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Chapter 2

of cartographic space, for example, seen on the bronze plate square outer wall of his city and then construct palaces, altars,

from the tomb of King Cuo of Zhongshan (see figure 2.7), is and markets inside it, the First Emperor constructed his pal-

evident on pine boards excavated in Tianshui, Gansu province, aces before he walled his capital, and the short duration of his

and dated 239 BCE.25 dynasty is the likely reason the outer wall was never completed.

From 677 to 383 BCE, the state of Qin was centered in The city was approximately 7.2 kilometers east-to-west by 6.7

the above-mentioned region Zhouyuan, which included the kilometers north-to-south, with its northern boundary along

modern cities Qishan, Fufeng, and Fengxiang, the locations the Wei River.

of building complexes and perhaps ancestral temples in the By the early twenty-first century, foundations of four build-

Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (see figures ing groups had been excavated. Evidence is strong that the

1.12, 1.13). This part of Shaanxi also contained enormous ducal first of them, known as palace 1, had at its core a two-story

tombs of the kind constructed across China in the middle of structure with seven rooms on the first floor and five upstairs,

the last millennium BCE. A 21-square-kilometer necropolis and with a central pillar extending from the ground to the

with some thirteen tomb areas, each with one or two main upper-story ceiling.28 Palace 2 is northwest of palace 1, and

tombs, includes the seventh-century BCE tomb of Duke Mu about the same size, but in a poorer state of preservation.

and the largest burial of the Spring and Autumn period, possi- Palace 3, the largest so far, was also two stories and was con-

bly the tomb of Duke Jing (r. 576–537); it is 5,334 square meters nected to palaces 1 and 2 by covered arcades. Its lower story

in area. Tombs believed to be royal are approached by long had eleven rooms. Murals done in mineral pigments remain

ramps from two sides like those in Anyang and King Cuo’s in palace 3. Subjects include acrobats, horses, animals, floral

tomb in the Zhongshan necropolis. Many of the tombs were motifs, geometric patterns, and architecture. The architectural

enclosed by moats, some by double moats, and some by “dry elements are especially interesting. Features such as tie-beams

moats,” perimeters dug as if to contain water. There is no evi- are painted along the upper walls where they would be found

dence of mounds above the Qin state tombs. in an actual building. The paintings anticipate a broader-based

In 383 the Qin state moved its capital farther north in imitation of architectural elements in relief sculpture or paint

Shaanxi to Liyang in Lintong county, near the site that would in later time that is known as fangmugou, imitation of the

become the capital of the Qin dynasty. Roof tiles, indications timber frame. Carbon-14 testing on wood from palace 3 dates

of streets, and wall pieces confirm its thirty-four-year exis- it to the mid–Warring States period, suggesting that painting

tence.26 Cruciform-shaped graves in Lintong are believed to and refurbishing probably occurred during the Qin, but older

belong to fourth-century BCE Qin dukes. They are different building parts were reused.

from the Qin state tombs in western Shaanxi in an impor- In addition, excavators believe they have found some of the

tant way: funerary temples were on top of the earlier tombs, palaces the emperor is reported to have built in imitation of

whereas the fourth-century burials were covered with mounds those of each of the final six states as he toppled them during

and funerary temples were nearby. his unification of China. Pottery tiles with the names of several

Initially Prince Zheng resided in palaces that remained from of the states have been uncovered on either side of palace 3.

the Qin capital of the Warring States period. Following unifi- Qin Shi Huangdi’s greatest achievement in palatial architec-

cation of the states in 221 BCE, he built new, larger palaces on ture was to be Epang Palace, immortalized in the Records of the

new sites. The Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) tells us that Grand Historian as a project for which the emperor conscripted

the First Emperor had three hundred palaces with another four more than 700,000 laborers and which, when it was destroyed

hundred outside the palace-city walls.27 What these numbers by the armies of the man who would found the Han dynasty,

refer to depends on how one defines palace, for as explained in burned for several months.29 The remains of Epang Palace are

the introduction, the character gong, translated as palace, can about 15 kilometers west of Xi’an in the vicinity of the Western

refer to one courtyard or more than twenty that are interre- Zhou capital Hao.

lated in a complex of palatial buildings. The outer boundaries The concept of a traveling palace (xinggong) also blossomed

of Qin Shi Huangdi’s capital also are vague: different from the under the First Emperor. The palatial residences in and around

dictum in “Kaogongji” that stipulates a ruler should build the the capital were a means of decoy for the ruler, information

28

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 28 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

2.11. Remains of Jieshi Palace,

Shibeidi, Suizhong, Liaoning, on

coast of Bohai Sea, Qin dynasty

about whose specific whereabouts at a given time could be 3,000-kilometer northern border, the First Emperor’s intent

punishable by death. Qin Shi Huangdi also used traveling was to join preexisting walls of former states into a single

palaces in the manner they would be used by emperors for the protective wall. He deserves credit for the idea of a bounded

rest of Chinese imperial history: he made inspection tours of nation, separate from nations beyond its borders, and per-

his empire to demonstrate and consolidate his power, inscrib- haps for understanding the symbolic power of a wall for

ing rocks and building residences at sacred and strategic sites China.

en route.30 He no doubt traveled on plank roads that had been The First Emperor did not accomplish his goals by being a

built in the Warring States period. Parts of one of these roads benevolent ruler. He resettled 120,000 families from defeated

between Xianyang and Sichuan province in the West remain states to serve him in the capital, conscripted hundreds of

today. Rocks and palace architecture survive at Jieshi on the thousands in his building projects, and is said to have burned

coast of the Bohai Sea in Liaoning, the xinggong most distant books of which he did not approve. Assassination attempts

from the capital. Announced by two rocks that rise from the on his life occurred with regularity, but none was successful.

sea as sides of an entryway, the coastal palatial area has been He died in his fiftieth year in 210 during one of his inspection

excavated as ten interrelated courtyards, most of which had tours, not having realized nearly what he hoped to accom-

building remains (figure 2.11). Ceramic tiles uncovered at plish. His minister Li Si kept the death a secret as long as pos-

Jieshi Palace confirm either that craftsmen from Xianyang sible, returning the body to the capital in a covered carriage

worked here or that their products were sent to the coast of filled with salted fish to disguise the smell of its more valuable

Liaoning province for installation.31 contents.32

Objects uncovered at all sites associated with the First No single tomb in China has aroused as much interest or has

Emperor confirm his vision of empire. Weights, money, been excavated or studied as intensely as the First Emperor’s.

and inscriptions prove that he unified weights and meas- For two thousand years, anyone who passed the truncated,

ures and established a national currency and a national pyramidal mound in Lintong county knew that China’s First

script. The last made it possible for documents to be written Emperor lay beneath it. The contents that continue to come out

and read by anyone, regardless of dialect. Qin Shi Huangdi of the ground since the announcement of the 7,000 life-sized

also established a central government in his capital and terra-cotta warriors in 1976 are so staggering that one indeed

divided the empire into commanderies, further dividing believes reports that 700,000 men labored there and that 16,000

them into prefectures. He had canals dug in order to trans- men carried away 42,000 tons of earth supplied by 200 diggers

port goods. He attempted to define the borders and protect over a period of 300 days.

his country by enclosing it in a Great Wall. Although the The mausoleum was begun in 246 when Prince Zheng

wall never stretched continuously across the approximately became King of Qin. Only the squarish mound, approximately

29

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 29 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Chapter 2

2.12. Plan of tomb complex of First

Emperor, Qin dynasty, Lintong,

Shaanxi

350 meters on each side, is above ground. No architecture has oil was used for lamps, which were calculated to burn for a

been found on it. Stairs led to the top. It is the central focus of a long time without going out.33

double-walled funerary precinct, the outer wall 6.21 kilometers

in perimeter with a gate in each face and the inner wall 3.87 This kind of replication of aspects of life in the microcosmic

kilometers in perimeter with two north gates and one at each world of the tomb would be standard funerary practice for

of the other sides. It is not as extensive as some royal funerary the rest of premodern Chinese history.

sectors of the past or future in China, no doubt because neither As has been the practice in China, and as occurred during

the emperor nor his dynasty endured long enough to realize excavation of the First Emperor’s palaces, the underground

his vision. Still, remains and literary descriptions indicate areas were numbered as they were opened. Pit 1, still not com-

extensive construction above ground (figure 2.12). The two pletely excavated, is 14,240 square meters and contains more

walls and the contents of pits suggest comparisons with the than seven thousand terra-cotta warriors and horses, twenty

double wall and underground spaces of the tomb of King Cuo wooden chariots, and about four thousand bronze weapons.

of Zhongshan (see figure 2.7). Beneath the mound the burial The L-shaped pit 2 is 6,000 square meters and has only infantry.

chamber remains sealed. Pit 3, 520 square meters, includes the elite soldiers and horses.

Records of the Grand Historian tells us that the tomb builders Pit 4 was found empty. Other subterranean pits contain small

numbers of terra-cotta officials, weapons, tools, 150 sets of

dug down to the third layer of underground springs and stone armor, 50 stone helmets, a 212-kilogram bronze tripod,

poured in bronze to make the outer coffin. Replicas of and cranes and other bronze birds.

palaces, scenic towers, and the hundred officials, as well as Qin Shi Huangdi’s own burial chamber has not been entered,

rare utensils and wonderful objects, were brought to fill perhaps because of the mercury (or cinnabar) believed, based

up the tomb. Craftsmen were ordered to set up crossbows on Sima Qian’s account, to have been used to preserve his

and arrows, rigged so they would immediately shoot down corpse; after more than two millennia of concealment the

anyone attempting to break in. Mercury was used to fashion atmosphere may be toxic. But perhaps it is because the aura

imitations of the hundred rivers, the Yellow River and of the First Emperor’s architecture holds unique intrigue even

the Yangzi, and the seas, constructed in such a way that among the myriad blockbuster finds that continue to emerge

they seemed to flow. Above were representations of all the from China’s soil. Moreover, the parts of the tomb beyond the

heavenly bodies; below, the features of the earth. “Man-fish” burial chamber are far from completely uncovered. In 2002,

30

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 30 12/21/18 1:05 PM

Architecture of the First Emperor

using remote sensing, archaeologists detected that the soil was city and its architecture was guided by writings of the first mil-

not uniform throughout the mound. Soil samples revealed that lennium BCE that declared the ruler’s mandate to reign from

the mound is not a single entity but rather two layers made the center of the world and an officialdom with subsidiary

of different materials, both of rammed earth, the inner finer political and social roles around him. This central position of

and of thinner layers than the outer. 3-D scanning determined the ruler was envisioned in the concept of Wangcheng, a plan

more precisely where the boundaries between inner and outer that was realized a few times in the first millennium BCE and

layers are. Also found under the mound in 2002 were pieces of would guide conceptions of the imperial city thereafter. Up

ceramic tile of the kind used in roofs.34 to the Qin dynasty, the most important centers of production

Excavation of the royal cemetery of Qi near the capital Linzi were also capitals, for the role of the capital and its architec-

in Shandong province in the twenty-first century also sheds ture was to serve its state or empire. Through the third century

light on the tomb of the First Emperor. Archaeologists found BCE, the greatest monumental architecture of China above

the burial chamber interfaced sub- and supraground levels. ground was also in cities, but already construction was emerg-

They called this tomb style qizhong, rising into the mound. ing in places visited by the emperor outside his capital such as

Similar burials were employed in Chu at Ma’anshan tomb 1 and on sacred peaks. Underground and outside, but near the ruler’s

at Pingliangtai tomb 16, suggesting the kind of layered con- city, tombs and ancestral temples signaled social relationships

struction beneath the mound also observed beneath the mound as clear as the location of a palace in its capital.

of King Cuo of Zhongshan. Roof tiles uncovered beneath the

mound in 2002 may be from an ancestral or sacrificial temple

on the mound, but it is also possible that roofed architecture

was inside the mound: the use of the mound to conceal passage

in and out of the tomb also is possible.

Construction underground will continue to change or

refine our understanding of Chinese architecture until the

final tomb in China is excavated. One writes based on infor-

mation gleaned from excavation in combination with tex-

tual sources about Chinese architecture of centuries BCE, but

always with the understanding that one new find may explain

or alter much that has been written to inform us of what we

do not yet know.

Architecture was crucial to Qin Shi Huangdi’s vision of em-

pire, but his fifteen-year reign was far too short to achieve it.

The most important period for this implementation would be

the next two hundred years, the period known as the Western

Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). The purpose of a capital, role of

the palace, and designs of ritual architecture and tombs con-

structed in the first two Han centuries would then be carried

forward for the rest of Chinese imperial history.

Even though the First Emperor worshiped at sacred spots

and established palaces across the land, part of his vision was

that the capital was the supreme city. Precedents for this con-

cept emerged in the Eastern Zhou dynasty when each state had

a designated palace-city. The understanding of the role of the

31

Brought to you by | Chalmers University of Technology

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/21/19 1:04 AM

Chinese Architecture v03c.indd 31 12/21/18 1:05 PM

You might also like

- NU632 Unit 4 Discussion CaseDocument2 pagesNU632 Unit 4 Discussion CaseMaria Ines OrtizNo ratings yet

- Calvino - The Daughters of The MoonDocument11 pagesCalvino - The Daughters of The MoonMar BNo ratings yet

- ISolutions Lifecycle Cost ToolDocument8 pagesISolutions Lifecycle Cost ToolpchakkrapaniNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutics Exam 3 - This SemesterDocument6 pagesPharmaceutics Exam 3 - This Semesterapi-3723612100% (1)

- Chapter 13 The Chinese Imperial City and Its Architecture Ming A 2019Document26 pagesChapter 13 The Chinese Imperial City and Its Architecture Ming A 2019Lajos OrosziNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 An Age of Turmoil Three Kingdoms 2019Document20 pagesChapter 4 An Age of Turmoil Three Kingdoms 2019Lajos OrosziNo ratings yet

- Annals Association American Geographers: UniversirDocument35 pagesAnnals Association American Geographers: Universircaozitian123No ratings yet

- TONG Tao - Ancient Chinese Cities - CompressedDocument35 pagesTONG Tao - Ancient Chinese Cities - CompressedlNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Genesis of Chinese Buildings and Cities 2019Document12 pagesChapter 1 Genesis of Chinese Buildings and Cities 2019Lajos OrosziNo ratings yet

- Chinese ArchitectureDocument78 pagesChinese ArchitectureAnupam SinghNo ratings yet

- Chang An Suburb Area Outside WallDocument15 pagesChang An Suburb Area Outside WallJoshua Immanuel GaniNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Chinese Settlement: Presented By: Adnan Irshad Kirti Pandey B.Arch Iii Yr SfsDocument25 pagesPresentation On Chinese Settlement: Presented By: Adnan Irshad Kirti Pandey B.Arch Iii Yr SfsKirti PandeyNo ratings yet

- Urban Planning - Chinese CivilizationsDocument15 pagesUrban Planning - Chinese CivilizationsVarunNo ratings yet

- Chinese Civilization: Made by - Anwesha Dutta Pamela Poddar Ritu OjhaDocument12 pagesChinese Civilization: Made by - Anwesha Dutta Pamela Poddar Ritu Ojharitu ojhaNo ratings yet

- Chronological Timeline of Chinese Architecture Through The DynastiesDocument13 pagesChronological Timeline of Chinese Architecture Through The DynastiesspraygilerNo ratings yet

- Orasele Chineze Pierdute, o Istorie Arheologica Din Neolitic Pana La Dinastia ZhouDocument3 pagesOrasele Chineze Pierdute, o Istorie Arheologica Din Neolitic Pana La Dinastia ZhouMircea BlagaNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in The Forbidden City The Magnificent Design Distinct Colors and Lucky Numbers of Chinas Imperial PalaceDocument9 pagesSymbolism in The Forbidden City The Magnificent Design Distinct Colors and Lucky Numbers of Chinas Imperial PalacelolalelaNo ratings yet

- HOA - Chinese ArchitectureDocument46 pagesHOA - Chinese ArchitectureChuzell LasamNo ratings yet

- Xia DynastyDocument6 pagesXia DynastycorneliuskooNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Engineering and Civilization in Ancient ChinaDocument21 pagesLesson 2 - Engineering and Civilization in Ancient ChinaVidya AneeshNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture 3 Module 3 (Part One) Chinese Architecture FeaturesDocument10 pagesHistory of Architecture 3 Module 3 (Part One) Chinese Architecture FeaturesMark Moldez100% (1)

- China and Indochina ArchitectureDocument13 pagesChina and Indochina ArchitectureAngelene PerochoNo ratings yet

- WuhanDocument1 pageWuhanVirat GadhviNo ratings yet

- Forbidden CityDocument7 pagesForbidden CityMRHNo ratings yet

- China: GeographyDocument37 pagesChina: GeographyShivaji GoreNo ratings yet

- Gr.7 - Usst - L-2 Engineering and Civilization NotesDocument3 pagesGr.7 - Usst - L-2 Engineering and Civilization NotesVidya AneeshNo ratings yet

- The Imperial Capitals of China: A Dynastic History of the Celestial EmpireFrom EverandThe Imperial Capitals of China: A Dynastic History of the Celestial EmpireNo ratings yet

- Chinese ArchitectureDocument8 pagesChinese ArchitectureMj JimenezNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet ChineseDocument2 pagesPamphlet Chineseapi-469787468No ratings yet

- B - The Empires of ChinaDocument67 pagesB - The Empires of ChinaMaryMelanieRapioSumariaNo ratings yet

- Media ArchitectureDocument7 pagesMedia ArchitectureKhoi Anh DoNo ratings yet

- Zu Chongzhi - The Chinese Calendar Reform of 462 ADDocument58 pagesZu Chongzhi - The Chinese Calendar Reform of 462 ADnqngestion100% (1)

- The Great Wall of ChinaDocument2 pagesThe Great Wall of ChinaMontseNo ratings yet

- Rahul DodiaDocument3 pagesRahul Dodiapintu_pspNo ratings yet

- The Great Wall of ChinaDocument2 pagesThe Great Wall of ChinaA S Rodríguez CastilloNo ratings yet

- History of Chinese ArchitectureDocument14 pagesHistory of Chinese ArchitectureMaribelleNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes 4: Architecture in ChinaDocument21 pagesLecture Notes 4: Architecture in ChinaAyelen ValleNo ratings yet

- Association of American Geographers, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Annals of The Association of American GeographersDocument36 pagesAssociation of American Geographers, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Annals of The Association of American Geographerscaozitian123No ratings yet

- Great WallDocument2 pagesGreat WallJames ManyuruNo ratings yet

- The Pyu Civilisation of Myanmar and The PDFDocument8 pagesThe Pyu Civilisation of Myanmar and The PDFအသွ်င္ ေကသရ100% (1)

- China: GeographyDocument39 pagesChina: GeographyShivaji GoreNo ratings yet

- Ming DynastyDocument7 pagesMing DynastyAryan RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- Chinese ArchitectureDocument105 pagesChinese ArchitectureKC Paner100% (1)

- Byzantium Persia and ChinaDocument11 pagesByzantium Persia and ChinaZalozba Ignis100% (1)

- Chinese Panorama Great Wall of ChinaDocument3 pagesChinese Panorama Great Wall of ChinaRoberto RomeroNo ratings yet

- Re300 Chinese ArchitectureDocument29 pagesRe300 Chinese Architecturealex medina100% (1)

- T S T S T SDocument2 pagesT S T S T SPaul LeggerNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture 3 AR123-1Document9 pagesHistory of Architecture 3 AR123-1Isaac AlegaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes - China 1Document5 pagesLecture Notes - China 1Mima PuzonNo ratings yet

- Cave TemplesDocument32 pagesCave TemplesIna ChiuNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Korean Architecture: July 4, 2006 1:30-3:30 Pm. Instructor: Heekyung LeeDocument11 pagesIntroduction To Korean Architecture: July 4, 2006 1:30-3:30 Pm. Instructor: Heekyung LeeKline MicahNo ratings yet

- History of China: Historical SettingDocument4 pagesHistory of China: Historical Settingcamiladcoelho4907No ratings yet

- 101 Facts... Ancient China: 101 History Facts for Kids, #10From Everand101 Facts... Ancient China: 101 History Facts for Kids, #10Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Chinese Dynasties: XIA DYNASTY: 2000 - 1500 BCDocument14 pagesChinese Dynasties: XIA DYNASTY: 2000 - 1500 BCupsidedownwalker100% (3)

- Illustrated Brief History of China: Culture, Religion, Art, InventionFrom EverandIllustrated Brief History of China: Culture, Religion, Art, InventionNo ratings yet

- Chinese ArchitectureDocument22 pagesChinese ArchitectureJohn Carlo Quinia100% (3)

- The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in The Planning of Ming BeijingDocument21 pagesThe Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in The Planning of Ming BeijingTAI CHI y CHI KUNG TerapéuticoNo ratings yet

- Yangtze International Study Abroad: Oracle Bones (jiăgŭwén - 甲骨文)Document77 pagesYangtze International Study Abroad: Oracle Bones (jiăgŭwén - 甲骨文)Anonymous QoETsrNo ratings yet

- The Great Wall of ChinaDocument2 pagesThe Great Wall of ChinaRaheel BaigNo ratings yet

- Great Wall of China - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument10 pagesGreat Wall of China - Britannica Online Encyclopediaal lakwenaNo ratings yet

- Chinese ArchitectureDocument9 pagesChinese ArchitectureMoon IightNo ratings yet

- Islam in China From Silk Road To SeparatismDocument27 pagesIslam in China From Silk Road To Separatismsekiz888No ratings yet

- Egg, Boiled: Nutrition FactsDocument5 pagesEgg, Boiled: Nutrition FactsbolajiNo ratings yet

- 10th PET POW EM 2023 24Document6 pages10th PET POW EM 2023 24rpradeepa160No ratings yet

- Orallichenplanus 170929075918Document40 pagesOrallichenplanus 170929075918Aymen MouradNo ratings yet

- Spek Dental Panoramic Rotograph EVODocument2 pagesSpek Dental Panoramic Rotograph EVOtekmed koesnadiNo ratings yet

- Service ManualDocument9 pagesService ManualgibonulNo ratings yet

- Ahmedabad BRTSDocument3 pagesAhmedabad BRTSVishal JainNo ratings yet

- BOSCH FLEXIDOME Multi 7000 - DatasheetDocument8 pagesBOSCH FLEXIDOME Multi 7000 - DatasheetMarlon Cruz CruzNo ratings yet

- Write A Short Note On Carbon FiberDocument4 pagesWrite A Short Note On Carbon FiberMOJAHID HASAN Fall 19No ratings yet

- Nursing Research VariablesDocument33 pagesNursing Research Variablesdr.anu RkNo ratings yet

- Prelim Kimanis Micom 241Document5 pagesPrelim Kimanis Micom 241Shah Aizat RazaliNo ratings yet

- The U.S. Biological Warfare and Biological Defense ProgramsDocument12 pagesThe U.S. Biological Warfare and Biological Defense ProgramsNika AbashidzeNo ratings yet

- 2414 2416 Installation ProcedureDocument4 pages2414 2416 Installation ProcedureJames BondNo ratings yet

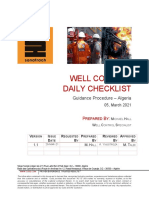

- Well Control Daily Checklist Procedure VDocument13 pagesWell Control Daily Checklist Procedure VmuratNo ratings yet

- Sulphur VapoursDocument12 pagesSulphur VapoursAnvay Choudhary100% (1)

- Magic HRC Scarf 1: by Assia BrillDocument6 pagesMagic HRC Scarf 1: by Assia BrillEmily HouNo ratings yet

- Shear Strength Prediction of Crushed Stone Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams Without StirrupsDocument2 pagesShear Strength Prediction of Crushed Stone Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams Without StirrupsSulaiman Mohsin AbdulAziz100% (1)

- Flex-10 Virtual ConnectDocument2 pagesFlex-10 Virtual ConnectArif HusainNo ratings yet

- BS en 480-6-2005Document5 pagesBS en 480-6-2005Abey Vettoor0% (1)

- Identifing Legends and CultureDocument2 pagesIdentifing Legends and CultureHezekaiah AstraeaNo ratings yet

- Hytrel Extrusion Manual PDFDocument28 pagesHytrel Extrusion Manual PDFashkansoheylNo ratings yet

- Engrave-O-Matic Custom Laser Engraving CatalogDocument32 pagesEngrave-O-Matic Custom Laser Engraving Catalogds8669No ratings yet

- An Open Letter To Annie Besant PDFDocument2 pagesAn Open Letter To Annie Besant PDFdeniseNo ratings yet

- LCOH - Science 10Document4 pagesLCOH - Science 10AlAr-JohnTienzoTimeniaNo ratings yet

- Design, Analysis and Simulation of Linear Model of A STATCOM For Reactive Power Compensation With Variation of DC-link VoltageDocument7 pagesDesign, Analysis and Simulation of Linear Model of A STATCOM For Reactive Power Compensation With Variation of DC-link VoltageAtiqMarwatNo ratings yet

- 9 Cartesian System of CoordinatesDocument15 pages9 Cartesian System of Coordinatesaustinfru7No ratings yet

- A 204Document1 pageA 204AnuranjanNo ratings yet