Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Flourishing 2016

Why Flourishing 2016

Uploaded by

Nengsih Tari0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views10 pagesOriginal Title

Why_Flourishing_2016

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views10 pagesWhy Flourishing 2016

Why Flourishing 2016

Uploaded by

Nengsih TariCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

11

ESSAY

Why Flourishing?

Corey Keyes

SCIENTISTS AND INVESTIGATORS of mental illness believe and convey to the public that

the treatment, cure, and prevention of mental illness are the only and the best ways to

promote the overall mental health of the population. Our nation continues to advocate

for doing more of the same thing for mental illness again and again but now expects a

different outcome, a cure. Our approach to mental illness is insane. Recent talk of find-

ing a cure for mental illness is promising too much at best or providing false promises at

worst. The Diagnostic and Stasistical Manual of Mental Disorders contains hundreds of

purportedly distinctive disorders, each characterized by a collection of signs and symptoms.

‘Will there be a single cure for all? Unlikely. Will we have to wait years for many cures for

all mental illnesses? Most likely. What is the cost to all who may become mentally ill

while we wait? More suffering and lost life,

Such calls for finding a cure may be effective for persuading the U.S. Congress to

devote more financial support to the National Institute of Mental Health. But I believe

that promising a cure for mental illness diverts atention and sesources away from a second,

viable, and complementary approach to mental illness—one that increases happiness.

Happiness is no laughing maccer, and promoting it might be just what we need to promote

good mental health and prevent some cases of common mental disorders.

Happiness, which is also called well-being, represents individuals’ evaluations of the

quality of theit lives. There are two approaches to and types of happiness: hedonic

happiness and eudaimonic happiness. The first approach frames happiness as positive

emotions and represents the opinion that a good life is measured by feeling good or

experiencing more moments of good feelings. The second approach frames happiness as

away of doing

by how well individuals cultivate their abilities to function well or to do good in the world.

gs in the world and represents the opinion that a good life is measured

Simply pus, happiness is feeling good or happiness is Functioning wel.

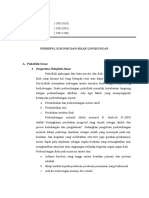

‘My own and others’ research revealed as many as fourteen facets of hedonic and

ceudaimonic happiness. Those facets are shown in Table 1 on the next page, and represent

the items or questions that form my measure of good mental health (ie., the Short Form

Questionnaire of the Mental Health Continuum). The first three items (happy, interested

in life, and satisfied) represent emotional well-being, che formal term I use to represent

the feeling good approach to happiness. The remaining eleven items represent the

functioning well approach to happiness. Of those eleven items, five represent social

well-being, which is the formal term for the different ways that we can assess how well an

individual functions as a citizen and member of a collective o community. The remaining

Why Flourishing? 9

Emotional Well-Being

louishing requtes almost cory day o every day on 1 oF more ofthe follwing

| How often during the past month did you feel |

|. Happy

oo |

|. Safed |

Positive Functioning

most evry day ot every day on 6 or more of the following: |

‘id you feel

| 4 thaeyou had something importans conta sce (oil conti

| Flourishing requires

How often during the past mon

5, That you belonged to a community (ikea social group, your school, or your neighborhood)

(social incegration)

& Thar erin bmi ever leo pope ik yo Gch gow |

| 7. Tha people are basically good (social zeceprance) |

“That che way our society works made sense you (socal coherence)

9, That oud mou parts of your penal alFacepancs) |

| 10. Good at managing the responsibilities of your daily life (environmental mastery) |

| 1 Thatyou tad van and unigiclombis wih or basin whos)

1. That you had experiences thac challenge you ro grow and become a beste person (personal growth) |

| 13. Confident co chin

or express your own ideas and opinions (autonomy) |

| 14. Thar your life has a

of direction oF meaning to it (purpose in life) _ |

six items represent psychological well-being, which is the formal term for the ways we

he difference between social

measure how well an individual functions in personal life.

and psychological well-being hinges on the pronoun and frame of mind: Social well-

being reflects our functioning as “we and us” (when I am a member of a larger group)

while psychological well-being reflects our functioning as “me and I” (when I am in my

private, personal, and incimace sphere of life).

You may have noticed earlier that I used the words mental health when referting to

happiness. In my own research, I argued that both kinds of happiness together help us to

measure and therefore study good, of positive, mental health. I call che pinnacle of good

‘mental health flourishing and chose that term to be clear that I am talking about true

‘mental health, not merely the absence of mental illness. | measure mental health in the

same way that psychiatrists measure common mental illnesses’To be diagnosed with

depression, for instance, one has to have a last one symptom of anhedonia (loss of pleasure

of loss of interest in life) combined with four of the seven symptoms of malfunctioning,

“To be diagnosed with flourishing mental health, individuals must experience in the past

month every day or almost every day at least one of the three signs of emotional well-bein,

ry day y iB

100 Wall-Being and Higher Education

combined with six or more of the signs of positive functioning. At the opposite end of

Aourishing on what I call the mental health continuum is languishing, which is diagnosed

by never ot once or swice during the past month having at least one sign of emotional

well-being combined with six or more signs of positive functioning. Individuals who

are neither flourishing nor languishing are diagnosed with moderate mental health.

Floutishing represents the achievement of a balanced life in which individuals feel good

ss is consistent

about lives in which they are functioning well. My approach to happi

with those views of happiness as more than secking and feeling pleasure. Buddhism, for

example, posits happiness as a wholesome and balanced state that includes a meaningful

and constructive approach to life. Such a view of happiness is consistent with Aristotle's

view of eudaimonia (translated as ew = good and daimon = soul or spitit) asa deliberate

way of being and acting in the world that is vireuous not only for oneself, but also for others

and the world.

‘Tue Two Continua Monet. AND THE Nos1e TRUTHS

While the more complete approach to measuring happiness allows us to approach mental

health positively, it has also allowed me to investigate what I consider the most fundamental

premise of pursuing happiness: the two continua model. In 1946, the World Health

Organization (WHO) defined health not merely as the absence of disease, but also as a

BAL OP at SAR eli Sn

seate of complete physical, social, and mental wel-being.? In doing so, the WHO declared

4 hypothesis that remained untested until very recently—that mental health is more

than the absence of mental illness; it is the presence of happiness or well-being. If this

hypothesis is supported, it has extremely important implications. First, even if we could

find a cure for mental illness tomorrow, ie docs not mean that most people would necessarily

be flourishing in life, In other words, we cannot treat our way out of the problem of mental

SES

illness; we must also promote a life of balance in which people can achieve happiness and

realize lives in which they can flourish.

T have found strong evidence in support of the two continua model in studies of

adults in the United States and the Netherlands, in black Setswana-speaking South AMticans,

and in youth ages 12 and older in the United States and Australia, We have also shown

that positive mental health, as I measure it, is just as heritable as common mental illnesses

(depression, panic attacks, and generalized anxiety). We then discovered that the two

continua model is encoded in our DNA because barely half of the genes for good mental

health are shared with the genes for mental illness. This means we inherit a genetic level

of tisk for depression while we also inherit a genetic potential for flourishing. However,

the absence of or very low genetic tisk for depression does not mean a high genetic

potential for flourishing. And the presence of high genetic tisk for depression does not

% mean a life doomed for depression because one might also plausibly inherit a high

y genetic potential for flourishing. What wins, depression or flourishing? It may very well

. depend on the kinds of experiences that unlock the genes for flourishing and what experi-

i ences silence the genes for depression. This focus may come in the future, but right now,

t the National Institute of Health supports research on genetic risk of mental illness, not

t genetic potential fot good mental health. In other words, we may be locking for the

% answer to the problem of mental illness in the wrong place by only Jooking at genetic

g risk rather than at genetic potential for flourishing,

a

‘Why Flourishing? 101

Ina recent study, we found that approximately 75 percent of American college students

were free of common mental illness as measured in the past two weeks. Yet only 46 percent

of college students were fice of mental illness and were also flourishing, In short, the

absence of mental illness does not imply the presence of mental health among college

students,’ and we found the same ching in adolescents? and adules.6

Another important implication of the qwo continua model is that the level of good

mental health should differentiate how well people with and without mental illness can

inua

model, For instance, almost 6 percent of college students are flourishing and also have

function in theie lives. All of my research has supported this aspect of the two cot

‘mental illness. These students have a lower risk of suicidal tendencies than the 17 percent

of college students who have moderate mental health with a mental illness. Roughly 3

percent of college students who are languishing and have

‘mental illness are at the highest risk for suicidal tendencies

Adults with less shan flourishing To be more specific, among students who would screen

mental health report more for a current mental illness, 7 percent who were flourishing

physical ailments and chronic showed suicidal tendencies, compared to 18 percent with

disease, miss more days moderate mental health and 28 percent with languishing

of work, use more health care mental health. When compared to students with mental

(more prescriptions, more illness, those currently free of mental illness are less

hospitalizations, more visits likely to have suicidal tendencies. Yet in this large group

for physical, mental, emotional of students (.e., the 75 percent free of a current mental

reasons), are more likely to die illness), those who are languishing have higher rates of

premavurely and are more suicidal tendencies than those with moderate mental

likely to develop mental illness health, who in turn have lower rates of suicidal tenden-

cies than students who are flourishing. More specifically,

among students who do not screen for a current mental

illness, only 1 percent of flourishing students showed suicidal tendencies, compared to 4

percent with moderate mental health and 15 percent with languishing mental health?

In short, anything less than flourishing is associated with worse outcomes for individuals

with and those frce of meatal illness. Adults with less than flourishing mental health

report more physical ailments and chronic disease, miss more days of work, use more

health care (more prescriptions, more hospitalizations, more visits for physical, mental,

emotional reasons), are more likely to die prematurely, and are more likely to develop

mental illness.*

Here again there are alignments with Buddhist views. T!

two continua model and

its implications share affinities with che Buddhist approach to enlightenment, namely

the four noble truths. These truths are as follows: (1) One must first understand the

nature of life as consisting of suffering because pleasure and satisfaction are fleeting and

life involves sickness, sadness, pain, and death; (2) One must understand the origin of

suffering; much of ic lows from our desires and expectations that encourage cravings

and attachment to things we encounter in daily life; (3) Ifwe can understand our role in

producing suffering, we can pursue the cessation of suffering (ie., nirvana) if we can rid

our heart and minds of the hindrances of greed, anger, ignorance, and hatreds (4) The

final eruth, which is the eightfold path, entails cultivating our ability to function well in

ing wisdom: (right understanding and right aspiration), ethical conduct

102 Wall Being and Higher Education

(right speech, right action and right livelihood) and mental development (right effore,

right mindfulness and sight concentration)

So after having grasped the nature and cause of suffering, and after avvempting to

mitigate it, Buddhists shift greater attention to the task of living good and happy lives.

This is done by pursuing wisdom through learning the truth about the imperfect nature

of life and human nature and living in a way that mitigates suffering caused by those

imperfections. We promote a beuter life by developing the ethical conduct of speaking

‘truthfully, compassionately, consistently with values and earning a living in a way that

does not hurt others and possibly helps others. Last, we promote a good life if we

develop our mental capacity by consistently trying to work on ie rather than making

excuses or procrastinating and by strengthening our minds and attuning them to recognize

and live in the present moment and situation,

Using this engaging metaphor or analogy of living or

being well together, the four noble truths and the eightfold | We must strive to act in ways

path illustrate the principles and implications of the two | that develop our capacity

continua model. That is, humans are prone to mental illness, | for doing and being good—

a form of suffering. Mental illness represents a form ofimbal- | ‘to contribute to society

ance of feeling and functioning, a state of mind and existence | to view ourselves and others

consisting of a disinterest in life, sadness, and malfunctioning. | as fundamentally good,

Buc mitigating mental illness through treatment or prevention | to develop warm and trusting

does not result in a flourishing life. Indeed, one way to over- relations with others—

come our vulnerability to mental illness is to achieve a bal- 50 that we come to feel pleasure

anced, wholesome life in which feeling good is connected to | about living our lives well

our ability to function well.

‘To flourish in life, we must understand that happiness as

feeling good may be the aim of our lives, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, but virtue

(and being in just relation with community) is the foundation for the fecling-good type

of happiness. So the absence of suffering does not mean one has achieved nirvana and

enlightenment, and the absence of mental illness does not mean one is flourishing. We

must strive to act in ways that develop our capacity for doing and being good—to contrib-

ute to society, to view ourselves and others as fundamentally good, to develop warm and

trusting relations with others—so that we come to feel pleasure about living out lives well.

In 1995, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, ages wenty-

five to seventy-five, and surveyed them again in 2005." Both times we measured good

mental health as a continuum as described carlicr and for the presence of common mental

disorders, including major depression episodes, panic attacks, and generalized anxiety

disorder. We found that 18.5 percent of adults had one of three mental disorders in

1995, and 17.5 percent had one of the three in 2005. Although the rate of mental illness

appears stable over time, just over half of the cases of mental illness in 2005 were new

ones (participants did not have any of the three mental disorders in 1995 but had one of

the three in 2005). So between 1995 and 2005, the United States made no. Progress in

reducing the cases of mental illness. While half of the 1995 cases were resolved in one

way or another, new cases emerged. These results suggest that the new cases emerged from

the group of people who were initially feee of mental illness but lost their good mental

health, which increased the risk of becoming mentally ill.

‘Why Hloueiching? 103

Compared to staying languishing, improving to moderate mental health cut the risk of

future mental illness by nearly half. Individuals who improved to Hourishing—most of

whom had moderate mental health in 1995—were no more likely than those who stayed

flourishing to have mental illness in 2005. Adults who improved to or stayed flourishing

had the lowest risk of developing mental illness. This suggests that we can prevent some

mental illness if we help more people to flourish.

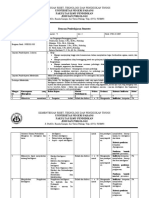

‘The numbers at the bottom of each bar in Figure 1 represent the proportion of the

sample that belongs to each category of mental health or mental illness. Because the

sample was designed to be representative of the U.S. adult population between the ages

of ewenty-five and seventy-five in 1995, we can use the percent in each category to esti-

mate how much of the U.S. adult population may be in each category of mental health.

‘The percentages of adults who stayed at moderate or improved or declined to moderate

mental health, when combined, represent nearly half (48.1% exactly) of the U.S. adult

population, and these adults are three to four times more likely to develop mei

illness

because they have moderate rather than Hourishing mental health. The percentages of

the sample that stayed at languishing or declined to languishing, when combined, repre-

sent one in ten (10.4% exactly) of the U.S. adults who are six to eight times more likely

to develop mental illness because they are languishing rather than flourishing,

In short, almost six in ten adults (10.4 languishing + 48.1% moderate = 58.5%) in

the study sample were not flourishing as of 2005. This large group of adults was free of

‘mental illness in 1995. Yee those languishing had greater risk (odds ratios between 6.6

and 8.2) of mental illness in 2005 than those adults who Aad mental illness in 1995

(whose odds ratio was 5.0). Adults with moderate mental health had nearly as high of a

risk (odds ratios between 3.4 and 4.4.) as adults wich a mental illness in 1995. So the

amount of any mental illness was 18.5% in 1995 and 17.5% in 2005, which suggests

that the United States did not make any significant progress in reducing mental illness.

But 52% of adults with mental illness in 2005 did not have any in 1995. Many of 52%

of new cases come from the large segment of people that does not have any mental illness

buc is not flourishing. If we fail to focus on promoring and protecting positive mental

health while we emphasize treating current cases of mental illness, we are unlikely to make

any progress in reducing the amount of and suffering from mencal illness.

How Can We Pursur FLourisHina?

Ifour or any other nation wants a mentally healthy population, it must take both kinds

of happiness seriously. We must promote what we want in our lives, and the concept of

flourishing challenges us all to prioritize and balance both kinds of happiness—to feel

‘good about lives in which we can function well. But how do we get there? The two

continua model requires us to think of new ways to achieve flourishing because treat-

ments that aim co lower the bad do nor necessarily increase the good. Just as with the

treatment for cholesterol, in which taking statins may lower bad cholesterol but will not

increase good cholesterol, mental health therapies aimed at lowering mental illness may

not increase mental health,

To that end, colleagues in the Netherlands developed and tested a public health approach

to promote mental health based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)."*

‘The point of ACT is to increase mental flexibility. This flexibility is a competence that

Why louishing? 105

includes two interdependent processes: (1) acceptance of negative experiences and (2)

choosing to change or persist in behavior based on values or principles. A person who is

mentally flexible is willing.¢o remain in contact rather than avoid negative, undesirable,

personal experiences. In other words, ACT promotes acceptance of the first noble cruth

of Buddhism (that suffering exists) because most of us try control or avoid such unwanted

private experiences. Rather than reacting emotionally co negative experiences, the ACT

program also encourages us to become conscious about making choices toward unwanted

experiences based on our values and goals for creating a good life

Based on ACT, Fledderus et al. developed a course that could be administered to

groups of people in a relatively brief period." Their program consists of a two-hour

session once per week for eight weeks. Through structured activities, participants are

encouraged to discover their values in multiple domains of life, and they are taught

how to respond to negativity and adversity based on their own deeply held commitments

and values. The course also teaches participants to be open and non-judgmental in per-

sonal experiences. The goal is for participants to learn to consistently choose effective

responses in any but especially in difficult situations to build behavior repertoires that

are flexible and value driven.

Continuing the analogy with the Buddhist strategy for living well, participants in the

ACT intervention are learning aspects of the Buddhist eightfold path. They learn that

adversity and negativity are natural and they can live in a way that mitigates the problems

caused by avoidance or repression of negative experiences. Participants then learn to

respond to adversity and negative emotions based on personal values. When compassion

meditation is included in the intervention, participants acquire the mindser (and dispo-

sition to behave or act) to live in a way that is more beneficial to others and, thereby,

themselves, When mindfulness meditation is included, participants learn to strengthen

their minds and to appreciate and live (act) in the present moment and situation."*

In owo randomized controlled trials, one that included mindfulness training,” my

colleagues found moderate to large effects for promoting flourishing. Because they also

measured mental flexibility, chey were able to test whether the program enhances mental

flexibility and if this enhancement of mental flexibility is the reason for increases in

flourishing, In both studies, mental flexibility explained how the program enhanced

flourishing. Impressively, che effects of the program were maintained three months lates.

Unfortunately, the design of the study did not allow for learning how much the inclusion

of mindfulness meditation added to the ACT program in promoting flourishing. Yee this

is just the beginning of a very important line of research that connects mind and life in a

way that promotes what we want more of in our lives: flourishing.

In sum, we must train our minds to focus on what matters, to make conscious choices

about how co best respond to the challenges and trials of life, to achieve a better balance

of prioritizing feeling with functioning well, and to be compassionate to others and our-

selves, No one can or should flourish all che time and everywhere, nor should anyone’

flourishing be at the expense of another’. I believe the ACT model can be used to encourage

a more sustainable approach to flourishing in life because it is based on promotion of the

happiness of others, not just one’s own.

106 Well-Being and Higher Rducasion

Notes

‘American Psychiatsic Association, The Diagnostic and Staitical Manual of Meneat Disorders, th ed

(Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

2. World Healch Organization, "Health,” Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,

beep: hwo. ine/radelglossary/sory046ren!

3. Coney L. M. Keyes, “Mental Health as a Complete State: How the Salurogenic Perspective Completes the

ictut,” in Bridging Occupational, Orgenizational and Public Health, ed. Georg F Bauer and Oliver Himmig,

(Dordrech, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands, 2014), 179-92,

4. Corey LM. Keyes et al, "The Relationship of Level of Positive Mental Health with Comrent Mental Disorders

in Predicting Suicidal Behavior and Academic Impairment in College Students,” Journal of American College

Heales 60, no, 2.2012}: 126-33,

5. Corey L. M. Keyes, “Mental Health in Adolescence: Is Ameticas Youth Flourishing?” American Joxonal of

Orthopsycbiaery 76, no, 3 (2006); 395-402.

6. Coney L. M. Keyes, “Mental Iiness and/or Mental Health? Investigating Axioms of the Complete Srate

Model of Health,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Pychology 73, no 3 (2005): 539-48,

7. Keyes eta. “Relationship of Level.”

8. Soe Keyes, “Mental Health as Complete Stare” and Corey L. M. Keyes and Eduardo J. Simoes, “To Flourish

or Not: Positive Mental Health and All-Cause Morality," American Journal of Public Health 102, no. 11

(2012): 2166-72.

‘9, Bhildehu Bodhi, “The Noble Bightfold Path: The Way to End Suffering,” Buddhist Publication Society

1998, heeps/fwww.cecessoinsight.orplib/authors/bodhifwaytoend tcl

10. Corey L. M. Keyes, Satvinder 8. Dhingra, and Eduardo J. Simoes, “Change in Level of Positive Mi

Healdh asa Predictor of Furore Risk of Mental Iles,” American Journal of Public Health 100, no, 12

(2010); 2366-71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245,

Ibid

‘ce Martine Fledderus et al, “Accepeance and Commitment Therapy 2s Guided Sel-help for Psychological

Distress and Positive Mental Health: A Randomized Controlled Tia.” Pyehological Medicine 42, no. 3 (2012):

485-95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001206 and Martine Fledderus et a, “Mental Health Promotion as

4 New Goal in Public Mental Health Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial ofan Intervention Enhancing

Paychological Flexibility,” American Journal of Public Health, 100, no. 12 (2010): 2372-78, doi: 10.2105)

AJPH.2010.196196,

13, Fledderus eta, “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.”

14, Hledderus eal, “Acecprance and Committnent Therapy” and Fledderus e al, "Mental Health Promotion.”

15. Ibid

‘Why Flowing? 107

+ LLL TT ee: cRNA NT a

Well-Being

and Higher Education

A Strategy for Change

and the Realization of

Education's Greater Purposes

Edited by Donald W. Harward.

Bringing Theory to Practice

Washington D.C.

i Bringing

red tO

toflld Practice

1818 R Street NW, Washington, DC 20009

(©2016 by Bringing’Theory co Practice

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-0-9853088-6-5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Laporan Kegiatan Harian Regita..Document7 pagesLaporan Kegiatan Harian Regita..Nengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Teori FNTDocument2 pagesTeori FNTNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Significant Life Change - Psikologi Emosi - Utari Oktavia NengsihDocument2 pagesSignificant Life Change - Psikologi Emosi - Utari Oktavia NengsihNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Laporan Harian MagangDocument7 pagesLaporan Harian MagangNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- TUGAS 4 PSIKOLOGI EMOSI Utari Oktavia NengsihDocument3 pagesTUGAS 4 PSIKOLOGI EMOSI Utari Oktavia NengsihNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Skala Kepribadian Big Five - Utari Oktavia NengsihDocument5 pagesSkala Kepribadian Big Five - Utari Oktavia NengsihNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Materi Kelompok 3 Psikologi LingkunganDocument10 pagesMateri Kelompok 3 Psikologi LingkunganNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Ratna Dyah Kusuma-Abstrak - P42122Document2 pagesRatna Dyah Kusuma-Abstrak - P42122Nengsih TariNo ratings yet

- RPS - Intelegensi Dan Bakat 2021Document7 pagesRPS - Intelegensi Dan Bakat 2021Nengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Persiapan Menulis ProposalDocument6 pagesPersiapan Menulis ProposalNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Naskah Publikasi - Eriza Divya Putri - 17081276Document14 pagesNaskah Publikasi - Eriza Divya Putri - 17081276Nengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Narkotika Dan KognisiDocument16 pagesNarkotika Dan KognisiNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Literatur Review - Utari Oktavia Nengsih - Isu PerkembanganDocument2 pagesLiteratur Review - Utari Oktavia Nengsih - Isu PerkembanganNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- 11.1. Administrasi Ro LanjutanDocument18 pages11.1. Administrasi Ro LanjutanNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Adaptasi Psikologis Dalam Persalinan Dan Dampak Kehamilan Terhadap Status Kesehatan Mental PerempuanDocument9 pagesAdaptasi Psikologis Dalam Persalinan Dan Dampak Kehamilan Terhadap Status Kesehatan Mental PerempuanNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Mekanisme Persalinan Bokong Dan MukaDocument6 pagesMekanisme Persalinan Bokong Dan MukaNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Sejarah Desain Tempat TinggalDocument6 pagesSejarah Desain Tempat TinggalNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Media Komunikasi TradisionalDocument18 pagesMedia Komunikasi TradisionalNengsih TariNo ratings yet

- Aplikasi Listrik Dalam Bidang KesehatanDocument19 pagesAplikasi Listrik Dalam Bidang KesehatanNengsih TariNo ratings yet