Professional Documents

Culture Documents

05 Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)

Uploaded by

anonymousOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

05 Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)

Uploaded by

anonymousCopyright:

Available Formats

DATE : 04 July 2022

FOR : ATTY. BEBELAN A. MADERA

Associate Solicitor III

(Group 6 Mentor)

FROM : GROUP 6 Members

Burdeos, Edmund Earl Timothy III H.

Estillore, Jiemar R. (Group 6 Representative)

Gigata, Mary Joy D.

Mallari, Pinky Antoinette A.

Nicer, Marianne Joy M.

Tolentino, Abygail A.

Wines, Nikoull C.

SUBJECT: FINAL DRAFT ENDORSEMENT OF MENTOR

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Atty. Madera,

Good Day!

As per the memorandum of the OSG LIP 2022 Committee, our fifth assignment is to

submit the final draft of our legal article.

With this, our group submits this draft for your evaluation and endorsement. As with the

previous submission, attached is the “Mentor’s Endorsement” which you may sign to be

submitted by the group.

Thank you very much!

Respectfully yours,

JIEMAR RILLORAZA ESTILLORE

Group 6 Representative

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 1 of 15

MENTOR’S ENDORSEMENT

To: OSG LIP 2022 COMMITTEE

Thru: ATTY. AIZA KATRINA S. VALDEZ

State Solicitor

FINAL DRAFT

Eliminating Gender-Based Discrimination: Harmonizing the Provisions on Adultery and

Concubinage (Articles 333 and 334) in the Revised Penal Code

I. Understanding Gender-based Discrimination

The right to equality and non-discrimination was not easily adopted by the international

community. Progress was made to intensively work on equality, but consecutive war occurred

from discriminatory practices affecting States. In dire need of protection for exploitation of

women then, United Nations General Assembly instituted on September 3, 1981, the

Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) 1 which

has been ratified by 189 states, noting that the Charter of the United Nations reaffirms faith in

fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights

of men and women.

Subsequently, on the 10th day of November 1989, the United Nations Office of the High

Commissioner for Human Rights adopted CCPR General Comment No. 18: Non-discrimination 2

at the Thirty-seventh Session of the Human Rights Committee. It states that non-discrimination,

together with equality before the law and equal protection of the law without any discrimination,

constitute a basic and general principle relating to the protection of human rights. Thus, Article

2, paragraph 1, of the International Covenant 3 on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) obligates

each State party to respect and ensure to all persons within its territory and subject to its

jurisdiction the rights recognized in the Covenant without distinction of any kind, such as race,

color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth,

or other status. Article 264 also prohibits any discrimination and guarantees to all persons equal

and effective protection against discrimination on any ground.

Later, by General Assembly Resolution 48/1045 dated December 20, 1993, it created the

only universal legal document explicitly for violence against women, Declaration on Elimination

of Violence Against Women. Article 3 of the Declaration states that women are entitled to the

equal enjoyment and protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political,

economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field. Its committee6 on the Elimination of

1

A/RES/34/180.

2

HRI/GEN/1/Rev.9(Vol. I).

3

United Nations (General Assembly). 1966. “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” Treaty

Series 999 (December): 171.

4

Id.

5

A/RES/48/104. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. United Nations. 1993.

6

UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), CEDAW General

Recommendation No. 19: Violence against women, 1992. https://www.refworld.org/docid/52d920c54.html

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 2 of 15

Discrimination against Women has stated regarding Articles 2(F), 5 and 10(C) of the

Convention7 on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women that “traditional

attitudes by which women are regarded as subordinate to men or as having stereotyped roles

perpetuate widespread practices involving violence or coercion, such as family violence and

abuse, forced marriage, dowry deaths, acid attacks and female circumcision. Such prejudices

and practices may justify gender-based violence as a form of protection or control of women.

The effect of such violence on the physical and mental integrity of women is to deprive them of

the equal enjoyment, exercise and knowledge of human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

On October 31st of 2000, the United Nations Security Council on its 4213th meeting

adopted Resolution 1325 (2000).8 It reaffirmed the important role of women in the prevention

and resolution of conflicts and in peacebuilding and stressed the importance of their equal

participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and

security, and the need to increase their role in decision-making vis-à-vis conflict prevention and

resolution.

At glance, we are undertaking something to eliminate, if not, lessen discrimination,

particularly, towards women. It was then followed by Study Report9 by the Secretary General on

Women, Peace and Security which urges Member States, entities of the United Nations and

civil society to ensure full participation of women and incorporation of gender perspectives. It

was viewed that the battle cry for gender equality is certain. That the masculine norm that

prevailed for centuries has to some extent reduced. Nevertheless, protecting women’s human

rights is a responsibility of all States mandated by human nature. In a Manual on Human

Rights10 by United Nations, it concluded that there are plenty of international legal provisions

guaranteeing the right to equality and non-discrimination. Thus, if discriminatory practices

persist around the world, it is not for the lack of legal rules but rather for lack of execution of

these rules in our societies. Inevitably, failure to implement some of the most fundamental

principles of international human rights law at domestic level also has a negative impact on both

internal and international peace and security.11

Equal treatment of men and women should be of primary concern of each States. As of

2014,12 143 countries have guaranteed equality between men and women in their Constitutions

but 52 have yet to take steps. Getting push back puts more women at a disadvantage,

particularly, in education translating into lack of access skills and limited opportunities. Women’s

and girl’s empowerment is essential to expand economic growth and promote social

development. Regardless of where you live, gender equality is a fundamental human right.

Advancing gender equality is critical to all areas of a healthy society, from reducing poverty to

promoting health, education, protection and well-being of girls and boys.

(last visited on 22 June 2022)

7

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 18

December 1979, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1249, p. 13,)

8

S/RES/1325(2000)

9

A/OSAGI/2004.

10

UN Doc. OHCHR. Human Rights in the Administration of Justice: A Manual on Human Rights for

Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers. Chapter 13: The Right to Equality and Non-discrimination in the

Administration of Justice.p.679

11

Id.

12

UN Doc. Gender Equality: Why it matters.

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Goal-5.pdf (last visited on June

22, 2022)

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 3 of 15

In the study conducted by Parmeter (2015), 13 it was concluded that a new understanding

of gender equality must look beyond female-centered measures and create room for men as

well. Incidents of discrimination against women vary, hence, the need for supplementing

enabling domestic laws equipped with the principle of gender equality that also prohibits gender

discrimination on all accounts. As this would be an inch closer to achieving gender equality.\

II. Extent of Gender-based Discrimination in the Philippines

In particular, the Philippines, from the study of Hauser (2017),14 has been successful at

achieving a higher degree of gender equality over other Asian countries, and much of the world

for many reasons. Article II Section 14 of the 1987 Constitution, 15 explicitly asserted that “the

State recognizes the role of women in nation building and shall ensure the fundamental equality

before the law of women and men. In addition, Article XIII Section 1416 provides that “the State

shall protect working women by providing safe and healthful working conditions taking into

account their maternal functions, and such facilities and opportunities that will enhance their

welfare and enable them to realize their full potential in the service of the nation”.

With the constitutional provisions to widen its principles, numerous legislations were enacted

that relate to the various aspects of women and gender concerns. The list includes:

● Gender and Development Law17 where 5% of government agencies’ budget is for

gender concerns

● Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 199518 which defines sexual harassment and providing

mechanisms

● Anti-Rape Law of 199719 which elevates rape as crime against person

● Women in Nation-Building law20 which allocates a budget for women from development

funds from foreign governments and multilateral institutions.

● Anti-Mail-Order-Bride Law21 making the long practice unlawful.

● Military Training Equality where women can enter the military and police schools and

provide facilities for them.

But these lack impact and don't show the actual situation in the country that would

illustrate actual success. For those positions in the legislative branch which has the power to

create, modify, alter, amend, and repeal laws; on the Fourteenth Congress,22 women in the

Senate merely compose 16.67% of the total seating capacity or 4 out of 24 and on the Fifteenth

13

Keith Cunningham Parmeter, Un(Equal) Protection: Why Gender Equality Depends On Discrimination,

2015, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?

article=1190&context=nulr (last visited Jun 22, 2022).

14

Cassandra E Hauser, Gender Equality in Southeast Asia: A Comparative Study of Indonesia And The

Philippines, 2017. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1046843.pdf (last visited Jun 22, 2022).

15

Phil. Const. art. II, sec. 14

16

Id., art. XIII, sec. 14

17

Rep. Act No. 9710

18

Rep. Act No. 7877

19

Rep. Act No. 8353

20

Rep. Act No. 7192

21

Rep. Act No. 6955

22

List of Previous Senators. https://legacy.senate.gov.ph/senators/senlist.asp#fourteenth_congress (last

visited on June 22, 2022)

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 4 of 15

Congress,23 taking a measly 12.5% or 3 out 24 seats. Over the years taking 25% or 6 out of 24

seats in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Congress.24 And making a small push to take 29.17% or

7 out of 24 seats in the Senate during the Eighteenth25 and to the Nineteenth Congress.

The statistics on women remain indicative of the deep-rooted and widespread problems

they encounter in their daily lives. The labor market has stereotyped women, disadvantaged

them in jobs and incomes, and even forced them into prostitutions and slave-like work. The

social image of a Filipina is still that of a weak person, poster girl of domestic help, expert in

double burden and a sexual object.26 In instance, the Committee expressed concern about

violence against women in Jordan and Iraq in the form of “honor” killings; under Article 340 of

the Jordanian Penal Code, “a man who kills or injures his wife of his female kin caught in the act

of adultery” is excused. The Committee urged Jordan “to provide all possible support for the

speedy repeal of article 340 and to undertake awareness-raising activities that make ‘honor

killings’ socially and morally unacceptable”.27

In the Philippines, honor-based violence is defined as an offense disproportionately

committed against women, which “has or may have been committed to protect the honor of the

family and/or community”. Beyond being a customary practice in some countries, laws in

defense of “honor” are sometimes in place which exempt husbands or family members from

criminal liability for the killings or violence inflicted against their wives, daughters, or sisters if

these women’s sexual behaviors defy societal or cultural gender norms or standards and thus

besmirch the patriarchal family’s honor or reputation.28

Strictly speaking, Article 247 does not actually define a crime. It provides, rather, a

defense which may be invoked by the accused if the killing or infliction of injuries was done

under the circumstances under the said provision. In essence, Article 247 presumes that a

spouse or a parent is acting in a “justified burst of passion”. However, this comes at the expense

of the safety and security of others, especially women.

While the first two paragraphs of Article 247 of the RPC are applicable to both spouses,

case records show that victims are predominantly the wives. Moreover, the third paragraph of

Article 247 pertains only to daughters and not the sons. These clearly show that the law is

based on discriminatory gender-based assumptions.29 Hence, Former Senator Manny Villar

then filed Senate Bill 2575.30 An Act Repealing Article 247 of Act No. 3815, Also Known as The

Revised Penal Code, On Death or Physical Injuries Inflicted Under Exceptional Circumstances

23

Id.

24

Id.

25

Id.

26

Carlos Antonio Q. Anonuevo. September 2000. An Overview of the Gender Situation in the Philippines.

https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/philippinen/50069.pdf (last visited June 22, 2022)

27

UN doc. GAOR, A/55/38, p. 20, para. 178-179 (Jordan),

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N00/611/52/PDF/N0061152.pdf?OpenElement (last

visited on June 22, 2022)

28

Upholding the Right to Life and Security of Spouses and Daughters: Repealing Article 247 of the

Revised Penal Code. Policy Brief No. 10. March 19, 2020, https://pcw.gov.ph/upholding-the-right-to-life-

and-security-of-spouses-and-daughters-repealing-article-247-of-the-revised-penal-code/ (last visited on

June 22, 2022)

29

Id.

30

Senate Bill 2575 on 15th Congress

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 5 of 15

in the Fifteenth Congress which would neutralize the provisions. However, until now, it is still

pending on the Committee of Constitutional Amendments, Revision of Codes and Laws.

In contrast with Article 333 and 334, these provisions manifest gender bias. RPC Articles

333 and 334 violate the equal protection clause of the 1987 Constitution since the sex-based

classification does not justify the setting of different elements for the same act of engaging in

extra-marital relations. Moreover, the justification for harsher penalties for the crime of adultery,

as first laid down by the Supreme Court in 1911, may no longer be applicable a century later.

Questions on the paternity and filiation of children could already be resolved by availing of the

remedies under Articles 172, 173 and 175 of the Family Code; and by medical advancements

such as DNA testing.

The criminalization of marital infidelity does not only impact women and men

disproportionately, but it also constitutes excessive State interference in the private lives of its

citizens, which violates fundamental law. Private sexual activities between consenting adults are

covered by the principle of privacy as enshrined in the International Convention on Civil and

Political Rights (ICCPR) and jurisprudence based thereon. Laws that penalize marital infidelity

in effect, infringe upon the rights of consenting adults to their privacy.31

International human rights law is, of course, fully applicable to women. The rights

described are equally relevant to women and the female juvenile. However, as evidenced by list

of treaties and declarations, it has been considered necessary, to deal more efficiently with the

serious and multiple violations of the rights of women that still exist in most countries, including

widespread discriminatory practices, to draw up separate gender-specific legal documents

focusing on the needs of women.32

III. The Guarantee of the Equal Protection Clause

The Philippines guarantees the equal protection of a person through the 1987

Constitution.33 Apart from the equal protection clause, the 1987 Constitution likewise provides

for rights which specifically pertain to women, among which are: the recognition of the “role of

women in nation-building”, the State policy that “ensure[s] the fundamental equality before the

law of women and men,”34 and the guarantee of the protection of “working women by providing

safe and healthful working conditions, taking into account their maternal functions, and such

facilities and opportunities that will enhance their welfare and enable them to realize their full

potential in the service of the nation.”35

Equal protection under the laws suggests the entitlement of persons and things similarly

situated to the same treatment, “both as to rights conferred and responsibilities imposed.

Natural and juridical persons are entitled to this guarantee; but with respect to artificial persons,

31

Repeal of RPC provisions on Adultery and Concubinage. Policy Brief. March 18, 2020.

https://pcw.gov.ph/repeal-of-rpc-provisions-on-adultery-and-concubinage/#:~:text=It%20is

%20recommended%20that%20Articles,should%20be%20civil%20in%20nature. (last visited on June 22,

2022)

32

UN Doc. OHCHR. Human Rights in the Administration of Justice: A Manual on Human Rights for

Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers. Chapter 11: Women’s Right in the Administration of Justice.p.447.

33

Phil. Const. art. III, § 1.

34

Phil. Const. art. II, § 14.

35

Phil. Const. art. XIII, § 14.

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 6 of 15

they enjoy the protection only insofar as their property is concerned.” 36 In Tolentino v. Board of

Accountancy, the Supreme Court explained that the clause means “that no person or class of

persons shall be denied the same protection of the laws which is enjoyed by other persons or

other classes in the same place and in like circumstances. (Missouri vs. Lewis, 101 U.S. 22,

31.)”37

In order to validly classify subjects of legislation and invoke the non-applicability of the

equal protection clause, the following requisites must be met: “(1) [the law] is based on

substantial distinctions which make real differences; (2) these are germane to the purpose of

the law; (3) the classification applies not only to present conditions but also to future conditions

which are substantially identical to those of the present; (4) the classification applies only to

those who belong to the same class.”38

In several cases, the Supreme Court applied equal protection in various instances

covered by provisions under different statutes, and even the Constitution itself. For instance, the

Court recognized the equal protection granted to local hires as against foreign hires by an

international school39, and acknowledged the entitlement to the imposition of taxes over all

sugar centrals in the city of Ormoc instead of just one sugar central. 40 On the other hand, the

Court held as valid the classifications made with respect to female domestic overseas workers 41,

the exercise of retail trade by Filipinos against the exercise by aliens 42, and the difference of

treatment of PNP members as opposed to “other classes of persons charged criminally or

administratively insofar as the application of the rule on preventive suspension is concerned” 43,

among others.

The Philippines is replete with laws which provide for equal protection to different

classes or groups of individuals. For instance, the Congress enacted a landmark legislation

which provides for an exhaustive list of the rights of women, among which are right against

discrimination and the right to pursue equal opportunities. 44 Other examples are the following:

laws that recognize that women and children are entitled to a special protection against

violence45, protect children and provides for the policies and guidelines with respect to their

employment46, grant special rights and privileges to disabled persons47, and ordinances issued

36

Antonio E.B. Nachura, Outline Reviewer in Political Law, p. 105 (2014).

37

Tolentino v. Board of Accountancy, G.R. No. L-3062, 28 September 1951.

38

Ormoc Sugar Co. Inc. v. Treasurer of Ormoc City, G.R. No. L-23794, 17 February 1968.

39

International School Alliance of Educators v. Quisumbing, G.R. No. 128845, 1 June 2000.

40

Ormoc Sugar Co. Inc. v. Treasurer of Ormoc City, G.R. No. L-23794, 17 February 1968.

41

Philippine Association of Service Exporters v. Drilon, G.R. No. 81958, 30 June 1988.

42

Ichong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, 31 May 1957.

43

Himagan v. People, G.R. No. 113811, 7 October 1994.

44

An Act Providing For The Magna Carta Of Women [The Magna Carta of Women], Republic Act No.

9710 (2009).

45

An Act Defining Violence Against Women And Their Children, Providing For Protective Measures For

Victims, Prescribing Penalties Therefore, And For Other Purposes [Anti-Violence Against Women and

Their Children Act of 2004], Republic Act No. 9262 (2004).

46

An Act Providing For Stronger Deterrence And Special Protection Against Child Abuse, Exploitation

And Discrimination, And For Other Purposes [Special Protection of Children Against Abuse, Exploitation

and Discrimination Act], Republic Act No. 7610 (1992) (as amended).

47

An Act Providing For The Rehabilitation, Self-Development And Self-Reliance Of Disabled Person And

Their Integration Into The Mainstream Of Society And For Other Purposes [Magna Carta for Disabled

Persons], Republic Act No. 7277 (1992) (as amended).

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 7 of 15

by local government units that prohibit gender-based discrimination. 48 Even the Civil Code

provides that every person must act with justice 49, and respect the dignity, personality, privacy

and peace of mind of other persons.50

Notwithstanding the above laws and ordinances, women continue to face and suffer

gender-based discrimination by reason of the different treatment in political, social, economic,

and other fields. Women are often denied the equal protection of their rights despite the

recognition of their role in nation building. While discrimination is addressed and prevented by

the State through legislation, it is likewise often manifested in the laws themselves. Among the

discriminatory laws is the specific provision under the Revised Penal Code which penalizes

adultery and concubinage.

IV. Articles 333 and 334 of the Revised Penal Code Manifests Gender Bias

While the rest of the world moves forward, the Philippines remains to be one of the

countries in the Asia-Pacific Region which penalizes adultery and concubinage as crimes

against chastity under the Revised Penal Code. 51 Both crimes are likewise treated as sexual

infidelity under the Family Code. 52 Although these crimes both refer to marital infidelity, a side-

by-side comparison of the two provisions and a survey of its jurisprudential development, it

becomes apparent that the law places the wives at a greater disadvantage than the husbands. 53

The disparity in the provisions with regard to the definition, the evidentiary proof required, and

the penalties imposed upon the offending parties, are summarized, thus:

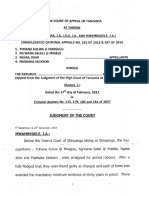

Art. 333 Art. 334

Definition Adultery is committed by any Any husband who shall keep a

married woman who shall have mistress in the conjugal dwelling,

sexual intercourse with a man or shall have sexual intercourse,

not her husband and by the man under scandalous

who has carnal knowledge of her circumstances, with a woman who

knowing her to be married, even if is not his wife, or shall cohabit with

the marriage be subsequently her in any other place.55

declared void.54

Required 1. The suing spouse is 1. That the man must be

48

Philippine Commission on Women, Enacting an Anti-Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and

Gender Identity Law (Policy Brief No. 11), available at https://pcw.gov.ph/enacting-an-anti-discrimination-

based-on-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-law/ (last accessed June 22, 2022).

49

An Act To Ordain And Institute The Civil Code Of The Philippines [Civil Code of the Philippines], art. 19

(1949).

50

Civil Code of the Philippines, art. 26.

51

An Act Revising the Penal Code and Other Penal Law [Revised Penal Code], Act No. 3815, arts. 333-

334 (1930).

52

The Family Code of the Philippines [Family Code], Executive Order No. 209, art. 55 (1987).

53

Philippine Commission on Women, Repeal of RPC provisions on Adultery and Concubinage (Policy

Brief), available at https://pcw.gov.ph/repeal-of-rpc-provisions-on-adultery-and-concubinage/ (last

accessed June 22, 2022).

54

Revised Penal Code, art. 333.

55

Revised Penal Code, art. 334.

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 8 of 15

Evidentiary married to the woman sued; married;

Proof 2. The woman sued had 2. That he committed any of

sexual intercourse with the following acts:

another man; and a. Keeping a mistress

3. That as regards the in the conjugal

paramour, he must know dwelling;

the woman to be married at b. Having sexual

the time that he had sexual intercourse under

intercourse with her.56 scandalous

circumstances with a

woman who is not

his wife;

c. Cohabiting with her

in any other place.

3. That as regards the

paramour, she must know

him to be married.57

Penalty Imposed Adultery shall be punished by Shall be punished by prision

prision correccional in its correccional in its minimum and

medium and maximum periods. medium periods.59

If the person guilty of adultery The concubine shall suffer the

committed this offense while being penalty of destierro.60

abandoned without justification by

the offended spouse, the penalty

next lower in degree than that

provided in the next preceding

paragraph shall be imposed.58

Figure 1. Differences between Adultery and Concubinage

Glaringly, the following distinctions can be made:

1. For a woman to be convicted of the crime of adultery, the man only needs to

prove that the woman had sexual intercourse with another man who is not her

husband. Meanwhile, for a man to be convicted of the crime of concubinage, the

woman is required to prove that any of the following circumstances occurred: a)

56

Nicolas & De Vega Law Offices, How to Sue your Wife for Adultery in the Philippines (Legal Advice),

available at https://ndvlaw.com/how-to-sue-your-wife-for-adultery-in-the-philippines/ (last accessed June

22, 2022).

57

Daniella Khylyn D. Glean, Punishing An Unfaithful Husband: Jurisprudential Development of Marital

Infidelity, available at https://lawreview.ust.edu.ph/punishing-an-unfaithful-husband-jurisprudential-

development-of-marital-infidelity/ (last accessed June 22, 2022).

58

Revised Penal Code, art. 333.

59

Revised Penal Code, art. 334.

60

Id.

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 9 of 15

that the man kept a mistress in the conjugal dwelling; b) that the man had sexual

intercourse under scandalous circumstances with a woman who is not his wife;

or c) that the man cohabited with another woman in any other place.

2. Despite the more stringent requirements that a woman must prove to

successfully convict a man for the crime of concubinage, the man convicted of

such crime suffers a lesser penalty than a woman convicted with the crime of

adultery.

The Supreme Court has justified the harsher penalties imposed in the crime of adultery

under the antiquated notion that such crime leads to the possibility of bringing illegitimate

children into the family without the knowledge of the husband. 61 With the advancements in

technology and the development of Philippine laws, such justification as first laid down by the

Supreme Court in 1911, may no longer be applicable a century later. In fact, questions on the

paternity and filiation of children could already be resolved by availing of the remedies under

Articles 172, 173 and 175 of the Family Code; and through DNA testing.62

Equality of all persons before the law is a specific constitutional guarantee wherein no

person is treated differently because of who he is or what he is or what he possesses. In Garcia

v. Drilon, the Supreme Court recognized the historical disparity between men and women as a

valid basis to uphold the constitutionality of a special law that specifically protected women and

children. Among others, the Supreme Court observed that there indeed exists an unequal power

relationship between women and men; the fact that women are more likely than men to be

victims of violence; and the widespread gender bias and prejudice against women.63 Instead of

balancing the scales in favor of an already disadvantaged group, the provisions on adultery and

concubinage under the Revised Penal Code continue to breed an imbalanced social structure

for women. It is said that the goddess of justice wears a blindfold to ensure that she will not

discriminate against suitors before her, and yet, in this case, it seems she wears the same in

complete disgust of the glaring prejudices the assailed provisions bring about.

V. Jurisprudential Treatment of Adultery and Concubinage

As early as 1930, the Supreme Court has observed the inequality between adultery and

concubinage. In Maulit v. Samonte,64 the Court noted that the authors of the Revised Penal

Code considered concubinage a lesser offense than adultery and therefore prescribed separate

and different penalties for the two offenses. In fact, Criminal Law experts are of the opinion that

the codal provisions on adultery and concubinage are terribly outmoded and should be

drastically revised.65 For instance, “married women may be convicted of adultery for having

sexual intercourse with any man not her husband, regardless of the validity of her marriage. On

the other hand, sexual relations of a married man with a woman who is not his wife is not

always a crime. It only becomes a crime if there is cohabitation, if it is committed under

scandalous circumstances, or if the sexual relations were committed with a married woman, and

he had knowledge of that fact.”66

61

Supra note 3.

62

Id.

63

Garcia v. Drilon, G.R. No. 179267, 25 June 2013.

64

Maulit v. Samonte, G.R. No. 34484, 13 December 1930

65

Estrada v. Escritor, A.M. No. P-02-1651 (formerly OCA I.P.I. No. 00-1021-P), Dissenting opinion of J.

Ynares- Santiago

66

People v. Caoili, G.R. Nos. 196342 & 196848, 8 August 2017, Dissenting opinion of J. Leonen

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 10 of 15

In Falcis III vs. Civil Registrar General, the Court explained that adultery is committed by

a wife who had sex with a man who is not her husband. In contrast, concubinage is committed

when a husband keeps a mistress in the conjugal dwelling, has sex under scandalous

circumstances, or cohabits in another place with a woman who is not his wife. While a woman

who commits adultery shall be punished with imprisonment, a man who commits adultery shall

only suffer the penalty of destierro. Further, a husband who engages in sex with a woman who

is not his wife does not incur criminal liability if the sexual activity was not performed under

"scandalous circumstances.”67 Indeed, provisions of adultery and concubinage differ severely in

terms of prescribed penalty. Adultery prescribes a penalty of prisión correccional in its medium

and maximum periods or imprisonment from 2 years, 4 months and 1 day to 6 years for both the

guilty wife and paramour whereas a penalty of prisión correccional in its minimum and medium

periods or imprisonment from 6 months and 1 day to a maximum of 4 years and 1 day for the

husband alone in the crime of concubinage and destierro for the concubine.

Adultery

Adultery is a crime of result and not of tendency. It is an instantaneous crime which is

consummated and exhausted or completed at the moment of the carnal union. Each sexual

intercourse constitutes a crime of adultery.68 Adulterous acts committed by the offenders are

made towards the offended husband, the status of the marriage, and the interest of the State in

maintaining and preserving such status of the husband and wife. Encroachment or trespass

upon the status protected constitutes a crime and there is no constitutional or legal provision

which bars the filing of as many complaints for adultery as there were adulterous acts

committed, thus each constituting one crime.69

The rationale for punishing the crime of adultery is the danger of introducing spurious

heirs into the family, whereby the rights of the real heirs may be impaired and a man may be

charged with the maintenance of a family not his own.70 In other words, the commission of

adultery may result in the introduction of another man’s blood into the family so that the

offended husband may have another man’s son bearing his (husband’s) name and receiving

support from him.71

Concubinage

Concubinage, similar to adultery, is a violation of the marital vow. However, concubinage

is different from adultery in the sense that infidelity of the husband does not bring into the family

spurious offspring.72

Unlike adultery which is consummated and completed at the moment of sexual

intercourse, concubinage may be committed in three ways: (a) by keeping a mistress in the

conjugal dwelling; (b) by having sexual intercourse, under scandalous circumstances, with a

woman not his wife, or (c) by cohabiting with her in any other place. 73 Thus, a married man is

liable for concubinage only when he does any of the three acts specified in Article 334 of the

67

Falcis III v. Civil Registrar General, G.R. No. 217910, 3 September 2019

68

Cuello Calon, Derecho Penal, Vol. II, p. 569

69

People v. Zapata, G.R. No. L-3047, 16 May 1951

70

U.S. v. Mata, G.R. No. L-6300, 2 March 1911; Pilapil v. Ibay-Somera, G.R. No. 80116, 30 June 1989

71

Luis B. Reyes, Revised Penal Code, 2021 Edition, p. 1140

72

Reyes, supra, p. 1136

73

Revised Penal Code, art. 334

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 11 of 15

Revised Penal Code. If his sexual relations with a woman not his wife is not any one of them, he

is not criminally liable.74

As to the first method of committing concubinage, the Supreme Court explained in U.S.

v. Macababbag, that a married man who keeps a mistress in his conjugal dwelling is guilty of

the crime of concubinage. "Scandalous circumstances" are not necessary to make him guilty of

said crime. It is only when the mistress is kept elsewhere that "scandalous circumstances"

become an element of the crime.75

With respect to the second way of committing the crime, i.e., concubinage by having

sexual intercourse under scandalous circumstances, the scandal produced by the concubinage

of a married man occurs not only when (1) he and his mistress live in the same room of a

house, but also when (2) they appear together in public, and (3) perform acts in sight of the

community which give rise to criticism and general protest among the neighbors.76

As to the third manner of committing concubinage, the court defined cohabitation in

People v. Pitoc as two people who dwell or live together as husband and wife; to live together

as husband and wife although not legally married; to live together in the same house, claiming

to be married; to live together at bed and board.77

A man cannot be guilty of concubinage without proving the presence of the three

circumstances leaving a more discriminatory view on penalizing women under adultery. Both

crimes are the same in nature where both are offenses against the sanctity of marriage yet

under the eyes of law, a woman’s crime is more obscene than that of a man’s. In sum, the law

sanctions monogamy. To strengthen this policy, the RPC treats extramarital affairs as felonies,

i.e., adultery and concubinage. But, in so doing, the law infringes on the right to equal

protection enshrined in the Constitution by discriminating against married women. Thus, the

provisions on adultery and concubinage under the RPC must be amended to safeguard the right

to equal protection and to carry out the Constitutional mandate 78 of ensuring the fundamental

equality before the law of women and men. However, this task of amendment belongs to

Congress, and not to the Supreme Court.

VI. Consequences of Repeal

With the repeal of the provisions on adultery and concubinage in the RPC, one may ask,

if the state condones forms of infidelity. As observed by the Philippine Commission on

Women,79 said provisions should be decriminalized or removed from the RPC since they involve

violation of marriage contract. Therefore, the policy recommendation is that the legal liability

should only be civil in nature.80 In support of this position, the repeal will not result in the total

74

People v. Santos, C.A., 45 O.G. 2216

75

U.S. v. Macababbag, G.R. No. 10564, 6 August 1915

76

Reyes, supra, p. 1138

77

People v. Pitoc, G.R. No. 18513, 18 September 1922

78

Phil. Const. art. II, sec. 14

79

Eliminating Discrimination Against Women in the Revised Penal Code (RPC): Decriminalizing Adultery

and Concubinage, available at https://pcw.gov.ph/eliminating-discrimination-against-women-in-the-

revised-penal-code-rpc-decriminalizing-adultery-and-concubinage/ (last modified 18 March 2020).

80

Ibid.

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 12 of 15

elimination of any kind of liability as there remains available remedies that can be resorted to by

the aggrieved parties.81

Under the Family Code, as to the civil matter, adultery and concubinage are still

illegal/unlawful so an aggrieved/offended/victimized spouse can still file for legal separation on

the ground of sexual infidelity, and/or a possible manifestation of psychological incapacity as a

ground for declaration of nullity of a marriage;82

Further, marital infidelity (concubinage) will continue to be one of the manifestations of

psychological violence against women under RA 9262 (Anti-Violence Against Women and Their

Children Act), a special law that protects women and their children from abuses and violence by

their husband and even intimate partners;83

On the other hand, sexual infidelity (adultery or concubinage) will continue to be one of

the bases for an aggrieved/offended/victimized spouse to sue for ordinary damages under the

Civil Code (i.e. psychological pain and suffering) against the offending/guilty spouse and the

third party involved.84

However, the position that adultery and concubinage will be no longer considered as

criminal offenses is untenable. Simply put, only maintaining civil liability for breach of marital

vows is not sufficient. Though marriage is civil in nature, it is not an ordinary contract. Even the

1987 Constitution recognizes the value of marriage as an inviolable social institution because it

is the foundation of the family and that the State is given the duty to protect it. As further

provided in the Family Code85, marriage is a special contract of permanent union between a

man and a woman entered into in accordance with law for the establishment of conjugal and

family life. As such, unlike ordinary contracts, the State is interested in ensuring that the parties

to a contract of marriage, which is special in nature, faithfully complies with the attendant legal

duties and responsibilities. The breach of such should not only amount to civil liability alone but

must still include criminal liability. Hence, there should be instead a marital or sexual infidelity

provision that should harmonize adultery and concubinage to remove the gender-based

discrimination in the RPC. With this, criminal liability still stands but with a single provision that

would cater to both men and women.

VII. Recommendation

This paper recommends that Articles 333 and 334 on Adultery and Concubinage under

the Revised Penal Code be repealed and replaced with a single provision penalizing marital

infidelity.

We propose the following amendments inspired in part by House Bill No. 529086:

81

Ibid.

82

Ibid.; Article 55 (88), Family Code.

83

Ibid.; Section 3(a), Republic Act 9262: Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004.

84

Ibid.; Article 2197, Civil Code.

85

Section 1, Family Code.

86

Press Release: “Amend gender-biased provisions of law on marital infidelity” available at

https://www.congress.gov.ph/press/details.php?pressid=9596&key=infidelity (Published on May 13,

2016).

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 13 of 15

“ARTICLE 333. Who are Guilty of Marital Infidelity. — Marital infidelity

is committed by:

1. any legally married person,

a. who shall keep a paramour in the conjugal dwelling; or

b. shall cohabit with a paramour in any other place; or

c. shall have sexual intercourse with another person other

than the married person’s spouse; and

2. by the person kept in the conjugal dwelling of the married person, or

who cohabits with the married person, or has carnal knowledge with the

married person, knowing the person to be legally married even if the

marriage be subsequently declared void.”

“ARTICLE 334. Penalties. — Marital infidelity shall be punished by

prisión correccional.

The penalty of prisión correccional in its maximum period shall be

imposed when the married person keeps a paramour in the conjugal

dwelling.

The penalty of prisión correccional in its medium period shall be imposed

when the married person cohabits with a paramour in any other place.

The penalty of prisión correccional in its minimum period shall be

imposed when the married person shall have sexual intercourse with a

person other than his/her spouse.

If the person guilty of marital infidelity committed the offense while being

abandoned without justification by the offended spouse, or, when the

accused spouse had been subjected to repeated physical violence or

grossly abusive conduct by the offended spouse, the penalty next lower in

degree than that provided in the next preceding paragraphs shall be

imposed.”

The proposed amendments retained the punishable acts under Concubinage except for

the requirement of scandalous circumstance in cases of sexual intercourse with another person

other than the married person’s spouse. The penalties provided also differ for each act with

heavier penalties imposed in cases where a paramour is kept in the conjugal dwelling or when

the married person cohabits with a paramour in any other place. Heavier penalties are imposed

on these cases as such acts are committed with public knowledge thereby causing immense

mental and emotional anguish, and public ridicule to the spouse and to their children, if there

are any. The act of keeping a paramour in the conjugal dwelling may also expose children to an

unhealthy family structure and make them vulnerable to abuse within the household.

On the other hand, penalties are mitigated when a person guilty of marital infidelity

committed the offense while being abandoned without justification by the offended spouse, or,

when the accused spouse had been subjected to repeated physical violence or grossly abusive

conduct by the offended spouse. Although these mitigating circumstances do not in any way

condone marital infidelity, the law wishes to grant partial relief in cases where the conduct of the

offended spouse contributed to what impelled the offending spouse to commit the offense.

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 14 of 15

The amended provisions also expand the coverage of the law by placing within its ambit

those cases wherein the paramour is of the same sex with the married offender. This addresses

the gap in the current version of the law where the act of infidelity cannot be punished under the

Revised Penal Code when the paramour is someone of the same sex.

I hereby certify that after due evaluation, the above-mentioned second draft of

the legal article is endorsed subject to the Committee’s approval.

Mentor: ATTY. BEBELAN A. MADERA

Associate Solicitor III

Signature:

Date Submitted: 04 July 2022 (Monday)

Date Approved:

Final Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP [Group 6] Page 15 of 15

You might also like

- Fifth report on human rights of the United Nations Verification Mission in GuatemalaFrom EverandFifth report on human rights of the United Nations Verification Mission in GuatemalaNo ratings yet

- 03 First Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)Document16 pages03 First Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)anonymousNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper 21st Ccentury Nigeria & The Un Convention On WomenDocument38 pagesSeminar Paper 21st Ccentury Nigeria & The Un Convention On WomenDele PetersNo ratings yet

- International Protection of The HR Cheridou SophiaDocument21 pagesInternational Protection of The HR Cheridou SophiaSophiaNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument9 pagesHuman RightsIsba KhanNo ratings yet

- International Human Rights Assignment: Convention On Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1979Document20 pagesInternational Human Rights Assignment: Convention On Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1979Sanjana MakkarNo ratings yet

- Pau 3104: Human Rights & Gender: Prof. J. MwimaliDocument9 pagesPau 3104: Human Rights & Gender: Prof. J. MwimaliGeneti TemesgenNo ratings yet

- CedawDocument8 pagesCedawYasirKhanNo ratings yet

- CEDAWDocument51 pagesCEDAWShannon Gail MaongsongNo ratings yet

- International MandatesDocument27 pagesInternational MandatesdarrelhatesyouNo ratings yet

- Right Against Racial DiscriminationDocument13 pagesRight Against Racial DiscriminationNivedhaprakashNo ratings yet

- Ender and Uman Rights: Submitted By: Aysha Zubaid Neha Imtiaz Fatima Karim Mcmbs4 University of GujratDocument40 pagesEnder and Uman Rights: Submitted By: Aysha Zubaid Neha Imtiaz Fatima Karim Mcmbs4 University of Gujratcreative humanNo ratings yet

- DomesticDocument3 pagesDomesticMesud GemechuNo ratings yet

- Early Marriage: A Violation of Girls' Fundamental Human Rights in AfricaDocument17 pagesEarly Marriage: A Violation of Girls' Fundamental Human Rights in AfricaRuxandra StanciuNo ratings yet

- HRL Final Assignment (1) Zain 01Document13 pagesHRL Final Assignment (1) Zain 01Zain RajarNo ratings yet

- Module 15 For Week 15Document14 pagesModule 15 For Week 15Khianna Kaye PandoroNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 4 Protection of Women'S Human Rights: International PerspectiveDocument31 pagesChapter - 4 Protection of Women'S Human Rights: International PerspectiveAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- MYP5 I - S U2 Notes Human - RightsDocument4 pagesMYP5 I - S U2 Notes Human - RightsVirenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 SOLIDARYCOLLECTIVE RIGHTS (THIRD GENERATION OF RIGHTS)Document7 pagesChapter 5 SOLIDARYCOLLECTIVE RIGHTS (THIRD GENERATION OF RIGHTS)I Lobeu My CaratNo ratings yet

- Women RightsDocument4 pagesWomen RightsSaddhviNo ratings yet

- The State of Qatar: United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)Document3 pagesThe State of Qatar: United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)Riska Dewi Puji HartantiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - Women Rights CedawDocument11 pagesAssignment 1 - Women Rights CedawBardha Sara Cleopatra Svensson100% (1)

- C E A F D W: by Dubravka ŠimonovićDocument6 pagesC E A F D W: by Dubravka ŠimonovićSajeev NKNo ratings yet

- Convention On The Rights of Persons With DisabilitiesDocument37 pagesConvention On The Rights of Persons With DisabilitiesNiluka GunawardenaNo ratings yet

- Universal Declaration of Human RightsDocument4 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human RightsAgot GaidNo ratings yet

- International Human Rights LAWDocument14 pagesInternational Human Rights LAWAbdul SukkarNo ratings yet

- Uncrpd: By: Ashmita Singh &tanya JainDocument20 pagesUncrpd: By: Ashmita Singh &tanya JainAshmita SinghNo ratings yet

- Advance Unedited Version: Freedom of Religion or BeliefDocument19 pagesAdvance Unedited Version: Freedom of Religion or BeliefJohanna Keren De los Reyes BatresNo ratings yet

- The Elimination of Racial Discrimination in All Its Forms in The WorldDocument6 pagesThe Elimination of Racial Discrimination in All Its Forms in The WorldAnita OkoyeNo ratings yet

- Human Rights and Disability: The International Context: J D D, V 10, N 2Document14 pagesHuman Rights and Disability: The International Context: J D D, V 10, N 2Neha JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Seven Core International Human Rights Treaties 4.1 International Convention On The Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Icerd)Document21 pagesSeven Core International Human Rights Treaties 4.1 International Convention On The Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Icerd)Francis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Unit IDocument16 pagesHuman Rights Unit IPRAVEENKUMAR MNo ratings yet

- Non-Discrimination in International Law A Handbook For Practitioners 2011 EditionDocument261 pagesNon-Discrimination in International Law A Handbook For Practitioners 2011 EditionAB-100% (1)

- UN Charter and UDHRDocument14 pagesUN Charter and UDHRRough ChannelNo ratings yet

- Legal Basis For Gender and SocietyDocument11 pagesLegal Basis For Gender and SocietyLance0% (1)

- JETIR2201089Document14 pagesJETIR2201089ChummaNo ratings yet

- African Human Rights LawDocument151 pagesAfrican Human Rights Lawzelalem shiferawNo ratings yet

- Essay On Gender Equality-Why An Issue PDFDocument4 pagesEssay On Gender Equality-Why An Issue PDFsalmanyz6No ratings yet

- Moeckli Chapter 19Document59 pagesMoeckli Chapter 19asdfg12345No ratings yet

- Rights of Women Paper HRDocument8 pagesRights of Women Paper HRMahnoor AsifNo ratings yet

- Assignment FinalDocument13 pagesAssignment FinalSukesan Poomalil SreedharanNo ratings yet

- Human Rights - Unit 2 - Sheikh MohsinDocument12 pagesHuman Rights - Unit 2 - Sheikh MohsinHindustani BhauNo ratings yet

- CEDAWDocument10 pagesCEDAWMario SantosNo ratings yet

- UNGA-SOCHUM Study GuideDocument14 pagesUNGA-SOCHUM Study GuideRaghav SamaniNo ratings yet

- Convention On The Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against WomenDocument7 pagesConvention On The Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against WomenBenedictTanNo ratings yet

- 14 - Suggestions and ConclusionDocument19 pages14 - Suggestions and ConclusionAlok NayakNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vienna Declaration and Programme For ActionDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Vienna Declaration and Programme For ActionDiksha GargNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument22 pagesHuman RightsptkabworldNo ratings yet

- CEDAWDocument11 pagesCEDAWaviralmittu100% (1)

- Women and Human RightsDocument27 pagesWomen and Human Rightsdinesh50% (2)

- Dev Verma Ba LLB HR Redg No 2041802037Document9 pagesDev Verma Ba LLB HR Redg No 2041802037Pranaya RanjanNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Objectives: 5 O Jec Ives 5 I R Tion: U N H Ma G y e 5 2 I VDocument15 pages5.0 Objectives: 5 O Jec Ives 5 I R Tion: U N H Ma G y e 5 2 I VNishanth TNo ratings yet

- HUMAN RIGHTS LAW (December 1-15 2021)Document11 pagesHUMAN RIGHTS LAW (December 1-15 2021)Eloisa AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Human Rights: Instructor: Shaimaa ElgamalDocument13 pagesHuman Rights: Instructor: Shaimaa ElgamalMira NabilNo ratings yet

- Women RightsDocument2 pagesWomen Rightstehreem buttNo ratings yet

- HR2 International Human Rights SystemsDocument16 pagesHR2 International Human Rights SystemsNokwethemba ThandoNo ratings yet

- CEDAW OverviewDocument7 pagesCEDAW OverviewTahir KhanNo ratings yet

- Solidarity/Collective Rights: (Third Generation of Rights)Document14 pagesSolidarity/Collective Rights: (Third Generation of Rights)AJ Layug100% (2)

- STS When Technology and Humanity CrossDocument17 pagesSTS When Technology and Humanity CrossJethru Acompañado67% (3)

- Traditional Knowledge, Genetic Resources and Traditional Cultural Expressions - Towards A Suitable Protection SystemDocument29 pagesTraditional Knowledge, Genetic Resources and Traditional Cultural Expressions - Towards A Suitable Protection SystemanonymousNo ratings yet

- Overview of Adjudication Proceedings in Intellectual PropertyDocument31 pagesOverview of Adjudication Proceedings in Intellectual PropertyanonymousNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Technology and LicensingDocument42 pagesTransfer of Technology and Licensinganonymous100% (1)

- Introduction To The Panel - Practicing IP in The Philippine Context - Opportunities and ChallengesDocument18 pagesIntroduction To The Panel - Practicing IP in The Philippine Context - Opportunities and ChallengesanonymousNo ratings yet

- Inventory of ExceptionsDocument5 pagesInventory of ExceptionsanonymousNo ratings yet

- Civil ComplaintDocument3 pagesCivil ComplaintanonymousNo ratings yet

- 03 First Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)Document1 page03 First Draft Endorsement of Mentor - OSG LIP (Group 6)anonymousNo ratings yet

- Comparative Models in Policing Chapter 2Document5 pagesComparative Models in Policing Chapter 2Gielhene MinearNo ratings yet

- Moot Cases and Professional Ethics Final PaperDocument7 pagesMoot Cases and Professional Ethics Final PaperMahnoor ParachaNo ratings yet

- Caballero, Krizah Marie C. Bsa 1a Gad Module 1 Learning ActivityDocument2 pagesCaballero, Krizah Marie C. Bsa 1a Gad Module 1 Learning ActivityKrizahMarieCaballero100% (2)

- 7 P V. S. M M I L M C C 2018: Case Concerning The Jurisdiction, Prisoners of War, Damages and Consular RelationDocument39 pages7 P V. S. M M I L M C C 2018: Case Concerning The Jurisdiction, Prisoners of War, Damages and Consular RelationSadia Nawrin100% (1)

- Three Fold RuleDocument1 pageThree Fold RuleChristian Rize NavasNo ratings yet

- Kingston Press Release and Resolution - MonumentsDocument4 pagesKingston Press Release and Resolution - MonumentsTristan HallmanNo ratings yet

- Correction: The Fourth Pillar of PCJSDocument19 pagesCorrection: The Fourth Pillar of PCJSMariel AlcazarNo ratings yet

- YEAR 1989 Sovereignty of States Natural Use of TerritoryDocument6 pagesYEAR 1989 Sovereignty of States Natural Use of TerritoryAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Bar NotesDocument26 pagesBar NotesGada AbdulcaderNo ratings yet

- Request of CA Justices Vicente S.E. Veloso, Angelita A. Gacutan and Remedios A. Salazar Fernando For Computation Adjustment of Longetivity PayDocument22 pagesRequest of CA Justices Vicente S.E. Veloso, Angelita A. Gacutan and Remedios A. Salazar Fernando For Computation Adjustment of Longetivity PayD MonioNo ratings yet

- FINAL GIUSTO Investigative Report #1 01 16 08 PDFDocument302 pagesFINAL GIUSTO Investigative Report #1 01 16 08 PDFmary engNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Cases PDFDocument143 pagesLegal Ethics Cases PDFIrene P. MartinezNo ratings yet

- CallejoDocument60 pagesCallejoKC SoNo ratings yet

- Lamera v. CADocument2 pagesLamera v. CANikitaNo ratings yet

- Yohana Kulwa at Mwigulu & 3 Others vs. R, Consolidated Criminal Appeals No. 397 of 2016, Mwambegele JADocument15 pagesYohana Kulwa at Mwigulu & 3 Others vs. R, Consolidated Criminal Appeals No. 397 of 2016, Mwambegele JAGervas GeneyaNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure ReviewerDocument229 pagesCivil Procedure ReviewerJoyce DalanginNo ratings yet

- E.O. 277 Amending P.D. 705Document3 pagesE.O. 277 Amending P.D. 705Chery ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION Sample QuestionsDocument4 pagesSTATUTORY CONSTRUCTION Sample QuestionsAw Ds Qe100% (1)

- Suit For Malicious Prosecution: March, 2022Document23 pagesSuit For Malicious Prosecution: March, 2022ebadNo ratings yet

- Brownlie International Law PDFDocument766 pagesBrownlie International Law PDFВасилий РомановNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 1Document24 pages07 - Chapter 1Tushar KapoorNo ratings yet

- Syllabus B L S LL BDocument7 pagesSyllabus B L S LL BLFC FanNo ratings yet

- The Legal System of Malacca SultanateDocument4 pagesThe Legal System of Malacca SultanateNur Rabiatuladawiah100% (1)

- Comparative Study BW IEA and Bhartiya Sakshya Bill, 2023Document11 pagesComparative Study BW IEA and Bhartiya Sakshya Bill, 2023Raju SwamyNo ratings yet

- Crim CircumstancesDocument81 pagesCrim CircumstancesliboaninoNo ratings yet

- Police Power (Cases)Document68 pagesPolice Power (Cases)Geraldine SalazarNo ratings yet

- ATP - BATCH 2 - 10 Cases - 4. de Jesus vs. Padilla Not IncludedDocument50 pagesATP - BATCH 2 - 10 Cases - 4. de Jesus vs. Padilla Not IncludedRomnick JesalvaNo ratings yet

- The Good Life - Week 6Document16 pagesThe Good Life - Week 6Joren JamesNo ratings yet

- SAMADocument1 pageSAMADiane JoyceNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Legality in NigeriaDocument17 pagesThe Principles of Legality in Nigeriaresolutions100% (5)