Professional Documents

Culture Documents

"Free Spaces" in Collective Action

Uploaded by

Jessica ValenzuelaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

"Free Spaces" in Collective Action

Uploaded by

Jessica ValenzuelaCopyright:

Available Formats

"Free Spaces" in Collective Action

Author(s): Francesca Polletta

Source: Theory and Society , Feb., 1999, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 1999), pp. 1-38

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3108504

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3108504?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and

Society

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

"Free spaces" in collective action

FRANCESCA POLLETTA

Columbia University

Good metaphors may be essential to social science. By putting "the

polysemous properties of language in the foreground," they facilitat

what Richard Harvey Brown calls the "genre-stretching" that drive

innovation.1 The danger of a good metaphor, though, is that claims

merely implied are subjected neither to theoretical specification nor

empirical investigation. Evocation substitutes for explanation. This ha

been the case, I argue, in recent discussions of the role of "free spaces

in mobilization. Since Sara Evans used the term in her 1979 Personal

Politics, "free spaces," along with "protected spaces," "safe spaces,"

"spatial preserves," "havens," "sequestered social sites," "cultural labo-

ratories," "spheres of cultural autonomy," and "free social spaces" -

different names for the same thing - have appeared regularly in the

work of sociologists, political scientists, and historians of collective

action.2 For all these writers, free spaces and their analogues refer to

small-scale settings within a community or movement that are removed

from the direct control of dominant groups, are voluntarily participated

in, and generate the cultural challenge that precedes or accompanies

political mobilization.

The term's appeal is considerable. Not only does it discredit a view of

the powerless as deludedly acquiescent to their domination, since in

free spaces they are able to penetrate and overturn hegemonic beliefs,

but it promises to restore culture to structuralist analyses without slip-

ping into idealism. Counterhegemonic ideas and identities come neither

from outside the system nor from some free-floating oppositional con-

sciousness, but from long-standing community institutions. Free

spaces seem to provide institutional anchor for the cultural challenge

that explodes structural arrangements. Yet the analytic force of the

concept has been blunted by inconsistencies in its definition and usage

and by a deeper failure to grasp the more complex dynamics of mobi-

Theory and Society 28: 1-38, 1999.

? 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2

lization. How ubiquitous are free spaces? How necessary are they to

mobilization and are they necessary to all movements? What makes

them free? The variety of answers to these questions stems in part from

the term's conflation of several structures that play different roles in

mobilization. That is, a feminist bookshop created by activists in the

American women's liberation movement bore a different relation to

protest than did a book circle in Estonia under Soviet rule.3 I suggest,

therefore, that we disaggregate structures as well as tasks of mobiliza-

tion. The three structures that I identify - transmovement, indigenous,

and prefigurative - can be compared along several dimensions. I argue

that the character of the associational ties that compose them, respec-

tively, extensive, dense/isolated, and symmetrical, helps to explain their

different roles in identifying opportunities, recruiting participants, sup-

plying leaders, and crafting compelling action frames.

This reconceptualization still does not answer to a second set of prob-

lems, which has to do with a tendency to reduce culture to structure, in

spite of the free space concept's promise to integrate the two. This is

most evident in discussions of what I have termed "indigenous" struc-

tures. Opposition is made dependent on the structural characteristics

of the free space (its density and isolation), and on the structural trans-

formations (opportunity or crisis) that turn the challenge nurtured

there into a mobilizing action frame. But that conceptualization

obscures, first, the cultural dimensions of structural transformations

outside the free space and, accordingly, insurgents' capacity to influ-

ence, indeed create, opportunities; and, second, the cultural specificity

of the structures within it. Depending on what meanings are attached

to actual or perceived ties, dense and isolated networks are as likely to

impede protest or limit it to purely local tragets and identities as to

facilitate it. Rather than providing insight into the dynamics by which

such constraints are surmounted, free spaces remain a cultural black

box grafted onto a political opportunity model or a structural break-

down one. Conceptualizing structures as cultural reveals resources

available to insurgents and obstacles facing them that have been over-

looked in analyses of free spaces.

Drawing on two cases whose status as free spaces has become near-

paradigmatic, I demonstrate the yields of such a reconceptualization. I

argue that network intersections are critical to generating mobilizing

identities, not just because weak-tied individuals provide access to

previously unavailable material and informational resources, but be-

cause their social distance endows them with the authority to contest

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

3

existing relations of status and deference among the aggrieved popula-

tion. Thus, I show how rural black Mississippians' interaction with

people they saw as representatives of the national civil rights move-

ment proved important in countering local black elites' reluctance to

engage in militant action. This was true even though the movement

activists to whom they were exposed, namely college-age organizers,

provided neither financial resources, physical protection, nor guarantees

of political success. Similarly, the development of a feminist challenge

within the Southern civil rights movement was made possible by

veterans' contact with white newcomers from Northern activist circles,

whose social distance not only brought new information and ideas, but

enabled them to defy conventions of racial and gender deference. In

both cases, mapping the structural relations without examining the

meanings of those relations is insufficient explanation for the timing

and form of collective action.

Theoretical convergence on the free space concept

In a much-quoted passage, Sara Evans and Harry Boyte write:

Particular sorts of public places in the community, what we call free spaces,

are the environments in which people are able to learn a new self-respect, a

deeper and more assertive group identity, public skills, and values of coopera-

tion and civic virtue. Put simply, free spaces are settings between private lives

and large scale institutions where ordinary citizens can act with dignity,

independence and vision.4

For Evans and Boyte and the scholars who have followed them, the free

space concept shows that the oppressed are not without resources to

combat their oppression. In the dense interactive networks of commun-

ity-based institutions, people envision alternative futures and plot strat-

egies for realizing them. Free spaces supply the activist networks, skills,

and solidarity that assist in launching a movement. They also provide

the conceptual space in which dominated groups are able to penetrate

the prevailing common sense that keeps most people passive in the face

of injustice, and are thus crucial to the very formation of the identities

and interests that precede mobilization. As Eric Hirsch puts it, "Havens

insulate the challenging group from the rationalizing ideologies nor-

mally disseminated by the society's dominant group."5 Free spaces have

included, by Fantasia and Hirsch's count, block clubs, tenant associa-

tions, bars, union halls, student lounges and hangouts, families, women's

consciousness-raising groups, and lesbian feminist communities.6

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4

The Southern black church, removed from white control and central to

the life of black communities, figures in most surveys of free spaces.

For the emerging civil rights movement it provided meeting places to

develop strategy and commitment, a network of charismatic move-

ment leaders, and an idiom that persuasively joined Constitutional

ideals with Christian ones.7 The Southern civil rights movement itself,

and particularly the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

(SNCC), in another oft-cited example, gave white women the organizing

skills, role models (in effective older women activists), and friendship

connections that were essential to the emergence of radical feminism.

It also gave them the ideological room to begin to question the gap

between male activists' radically egalitarian ethos and their sexist

behavior. "Within the broader social space of the movement," Evans

and Boyte write, "women found a specifically female social space in

which to discuss their experiences, share insights, and find group

strength as they worked in the office or met on the margins of big

meetings."8 Free spaces within movements thus contribute to the

spread of identities, frames, and tactics from one movement to another.

And as "abeyance structures"9 and "halfway houses," 10 they preserve

movement networks and traditions during the "doldrums" of apparent

political consensus. They are "repositories of cultural materials into

which succeeding generations of activists can dip to fashion ideologi-

cally similar, but chronologically separate, movements," as McAdam

puts it.11 As "movement communities," free spaces are an enduring

outcome of protest.12

The free space concept has been appealing to scholars of varying theo-

retical stripe for its recognition of the usually constraining operation of

common sense while refusing the across-the-board mystification of

dominant ideology theses. Counterhegemonic frames come not from

a disembodied oppositional consciousness or pipeline to an extra-

systemic emancipatory truth, but from long-standing community in-

stitutions. Converging with resource mobilization models' attentiveness

to the networks and organizations that precede insurgency, the notion

of free spaces highlights in addition the specifically cultural dimensions

of prior networks.13 It thus seems to provide a much needed concep-

tual bridge between structuralist models' focus on institutional sources

of change and new social movement theorists' interest in challenges

to dominant cultural codes. It recognizes the cultural practices of

subordinate groups (free spaces are often cultural institutions) as

proto- or explicitly political. The free space concept undermines another

well-worn opposition between tradition and radical change. Free spaces

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

5

are often associated with the most traditional institutions: the church

in Southern black communities;14 the family in Algeria and Kuwait;15

nineteenth-century French peasant communities.16 Although under nor-

mal circumstances such institutions are conservative, the rapid social

change that both threatens their existence and puts ancient ambitions

within reach may make of them, as Calhoun puts it, "reactionary radi-

cals." 17 Incorporating institutional and ideational dimensions, tradition

and change, and community and challenge, the free space concept seems

an ideal conceptual tool for probing the foundations of insurgency.

Divergence and ambiguity

Yet what seems like consensus on what the term "free space" means,

refers to, and illuminates conceals a good deal of divergence. What are

free spaces? Authors variously describe them as subcultures, commun-

ities, institutions, organizations, and associations, which are very differ-

ent referents. Evans and Boyte represent them as physical spaces; the

term, they say "suggests strongly an 'objective,' physical dimension -

the ways in which places are organized and connected, fragmented,

and so forth."18 However, Scott maintains that linguistic codes that are

opaque to those in power are as much a free space as is a physical site

of resistance; Farrell says that the 1950s Beat Movement created "free

spaces in print and performance"; Robnett describes the grassroots,

one-on-one recruitment activities that were dominated by women in

the civil rights movement as a "free space," and Gamson calls "cyber-

space" a "safe space."19

Do all oppressed groups have free spaces? Gamson and Scott argue

that only total institutions provide the powerful complete control; all

other regimes of power coexist with spaces of relative autonomy. Fan-

tasia and Hirsch similarly argue that "[t]hese 'free' social spaces or

'havens' have had counterparts wherever dominant and subordinate

groups have coexisted."20 But they go on to suggest that "the avail-

ability and nature of such 'free' spaces play a key role in the success of a

variety of movement mobilization efforts,"21 this implying that free

spaces are not always available. Hirsch reiterates the point: "Successful

recruitment to a revolutionary movement is more likely if there are

social structural-cultural havens available where radical ideas and

tactics can be more easily germinated."22 If not all oppressed groups

possess free spaces, then under what conditions do such sites emerge?

What about free spaces make them free, and free of what? There seems

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6

to be agreement among the authors I've cited that freedom from the

surveillance of authorities is essential.23 The hush arbors of slaves, bars

in working-class communities, Kuwaiti mosques under Iraqi occupa-

tion: each gave oppressed groups the opportunity to voice their com-

plaints and openly discuss alternatives. On the other hand, federal

prison served as a launching pad for the radical pacifist movement,

according to James Tracy. "In these artificial communities, [WW2 con-

scientious objectors] feverishly exchanged ideas about reforging paci-

fism and experimented with resistance against the microcosm of the

state they had near at hand in their places of internment."24 Whether

free spaces are characterized by ideological freedom is also disputed.

Evans and Boyte, Gamson, Hirsch, and Fantasia and Hirsch argue

that they are; James Scott claims that subordinates' apparent consent

to their domination is everywhere a performance.25 Free spaces offer

people not the opportunity to penetrate the sources of their subordina-

tion, since they are already obvious, but to preserve and build upon a

collective record of resistance. But what about groups that are not

subordinate? They launch movements too, for example, for animal

rights and environmental protection, but presumably lack a "hidden

transcript" of collective resistance. Do they require free spaces?

Small size, intimacy, and the rootedness of free spaces in long-standing

communities seem to be common themes. Evans and Boyte define

them in part "by their roots in community, the dense, rich networks of

daily life."26 Scott writes: "Generally speaking, the smaller and more

intimate the group, the safer the possibilities for free expression."27

And Couto: "When the conditions of repression are paramount and

the possibility of overt resistance is small, narratives are preserved in

the most private of free spaces, the family...."28 But intimacy is no

guarantee of freedom of expression. And as feminist theorists have

long pointed out, the family has been a prime site for the reproduction

of patriarchal relations.29 With respect to free spaces' deep community

roots, this doesn't seem to be the case with movement free spaces,

which are created de novo as a deliberate strategy for freeing up

discussion. In Hirsch's account of community organizing in East New

York, the "havens" within which an oppositional culture developed -

block clubs - were founded by organizers from outside the community.

The block clubs were the movement rather than precursors to it.30 The

Highlander Center, federal prisons, and the Christian Faith and Life

Community within which New Left ideals were developed have each

been labeled free spaces but none can be considered integral to the

daily life of pre-existing communities.31 1960s feminist activist Pam

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

7

Allen is explicit: "It is when we come into a long term relationship with

people with whom we don't associate regularly that the old roles we

play can be set aside for a space in which we can develop ourselves

more fully as whole human beings.... Free Space is free because we do

relate apart from our daily lives." 32

Finally, what are the connections between the counterhegemonic chal-

lenge that is nurtured in free spaces and full-fledged mobilization? For

Evans and Boyte, "Democratic action depends upon these free spaces,

where people experience a schooling in citizenship and learn a vision

of the common good in the course of struggling for change.... Free

spaces are the foundations for such movement countercultures."33

Fantasia and Hirsch argue, by contrast, that the alternative cultures

developed in such sites only become politicized in the context of insur-

gency. For Scott, the cultural practices in free spaces are already

political. However, insurgency is only triggered by a relaxation of sur-

veillance. For Whittier, activists turn to cultural work within free

spaces when direct engagement with the state is no longer possible.34

Are participants in the free space more likely to perceive political

opportunities when they open up? Do leaders within the free space,

for example, ministers or teachers, the local bartender, or conveners

of a consciousness-raising group within a movement, become the

leaders of the (new) movement? Do the institutions within which

opposition is nurtured shape the character of insurgency? And do free

spaces precede the emergence of all movements? Evans's and Boyte's

claim that free spaces are necessary to "democratic action,"35 and

Fisher's that free spaces are "seedbeds for democratic insurgency,"36

suggest their limited applicability. But is there any reason why free

spaces do not play a role in right-wing movements?

It seems clear that by "free space" analysts have something more in

mind than a gathering place that is removed from the direct surveil-

lance of authorities. It is hard to imagine insurgents not finding a

physical space for communication, whether a shadowy alley, a prison

exercise yard, or the internet. And indeed, in several cases the physical

space that analysts refer to doesn't seem to amount to much, for exam-

ple the "margins of big meetings" that Sara Evans identified as a free

space for the development of radical feminism within the New Left, and

the street corner defended against rival gangs that Gamson describes

as a safe space.37 Rather it makes sense to see the free space concepts

as an attempt to capture the social structural dimensions of several

cultural dynamics. We know that cultural practices can express, sus-

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8

tain, and strengthen oppositional identities and solidarities (especially

at times when repression makes direct claims on the state impossible,

but also when institutionalized understandings of politics exclude issues

and identities as personal, private, or otherwise non-political); that

movements build on prior activist networks, traditions, and know-

how; that pre-existing affective bonds supply the selective incentives

to participate rather than free-ride; and that community institutions

can nurture traditions of opposition to dominant ideologies. However,

the free space concept simply posits a "space" wherein those dynamics

occur, without specifying how, why, and when certain patterns of

relations produce full-scale mobilization rather than accommodation

or unobtrusive resistance. As a first cut at these questions, I propose

that we distinguish three types of associative structures that have been

called free spaces, and specify the ways in which each one is more and

less likely to facilitate key tasks of mobilization. Then I suggest what

such a typology leaves out.

An alternative: Structures of association and preconditions for

mobilization

Transmovement, indigenous, and prefigurative groups38 all operate

within or in sympathy with an aggrieved population and all foster

oppositional practices, whether explicitly political or proto-politically

cultural (see Table 1). I focus here on the character of their associa-

tional ties, both those linking participants and those linking particular

networks to others within a "multiorganizational field,"39 in account-

ing for their differential capacity to identify opportunities, supply

leaders, recruit participants, craft mobilizing action frames, and

fashion new identities, tasks essential to sustained mobilization. Note

that transmovement, indigenous, and prefigurative forms of associa-

tion by no means exhaust the structures that play a role in mobilization.

Most obviously missing are formal movement organizations, along

with counter-movements, third parties (media and funders), and

authorities. I treat only these three because they have been character-

ized as "free spaces" but without the differentiation necessary to iden-

tify the specific resources each provides for mobilization efforts. Note

also that my intention is not to privilege the character of social ties

over their substantive content in accounting for their role in mobiliza-

tion, that is, to privilege structure over culture. I understand culture

as the symbolic dimension of all structures, institutions, and practices

(symbols are signs that have meaning and significance through their

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

9

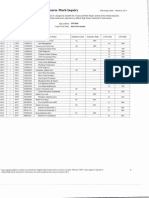

Table 1. Associative structures in social movements

Structure Character of Role in mobilization Examples

ties

Trans- Extensive Well-equipped to identify Highlander Folk School,

movement ties opportunities. Not well- National Women's

equipped to supply leaders Party, radical pacifists

or mobilizing frames, or to

recruit participants

Indigenous Dense ties, Well-equipped to supply Southern black church,

isolated leaders, local participants, German Turner halls,

network and mobilizing frames; but Estonian literary circles,

not to identify extra-local craft guilds

opportunities or mobilize

extra-local participants

Prefigurative Symmetric Well-equipped to develop "Women's only" spaces,

ties new identities and claims, new social movement

but unless they begin to "autonomous zones,"

provide non-movement "alternative" services

services are difficult to

sustain

interrelations; the pattern of those relations is culture). More on this

follows below.

Transmovement structures are the "halfway houses" described by Aldon

Morris, the "abeyance structures" by Verta Taylor, the "movement

midwives" by Christian Smith, and the "movement mentors" by Bob

Edwards and John McCarthy: the Fellowship of Reconciliation, High-

lander Folk School, and Southern Conference Educational Fund for

the civil rights movememt, the National Women's Party for second wave

feminism, and the American Friends Service Committee and Fellowship

of Reconciliation for the 1980s Central American peace movement.40

They are activist networks characterized by the reach of their ties geo-

graphically, organizationally, and temporally. That is, activists are

linked across a wide geographic area, have contacts in a variety of

organizations and are often veterans of past movements. At the same

time, they are marginal to mainstream American politics.41 Trans-

movement structures can be concentrated in a physical site like the

Highlander Folk School, which trained generations of activists in the

techniques of nonviolence and community organizing. Or they may

consist in a looser cadre of activists, for example, American radical

pacifists who operated in a variety of movement organizations in the

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10

New Left, anti-Vietnam War, and civil rights movements.42 Either way,

transmovement groups' extensive contacts position them to identify

changes in the structure of political bargaining that indicate the state's

likely vulnerability to movement demands.43 By comparison, locals'

distance from national political elites makes it difficult for them to

identify the splits and alliances that signal new prospects for successful

insurgency.44 Transmovement groups may provide funding for emerging

movements and for activists pursuing militant tactics or a radical

agenda, as well as legal advice and communications contacts.45 They

often train movement leaders in strategies and tactics (as radical pacifists

Glenn Smiley and Bayard Rustin did in honing Dr. King's knowledge

of Gandhian nonviolent resistance).46 On the other hand, transmove-

ment groups are not well-positioned to supply leaders, engage in re-

cruitment drives, or develop resonant mobilizing frames. For the U.S.

Central American peace movement, the "stability and bureaucratic

formality" of groups like the American Friends Service Committee

and the National Council of Churches "seem[ed] to produce a certain

sluggishness that inhibit[ed] the kind of high-intensity organizing

needed to mobilize insurgency," Christian Smith notes.47 In other

cases, the marginal and sometimes prosecuted status of transmove-

ment groups has made them of ambiguous benefit to leaders seeking

to present their movement as "homegrown" and deserving of main-

stream support. Radical pacifists' refusal to bow to movement real-

politik made them at times worrisome wild cards for moderate leaders

in the civil rights, New Left, and anti-Vietnam War movements.48 And

leaders of the African National Congress in the 1950s sought to disso-

ciate themselves publicly from the illegal South African Communist

Party, even as they sought its advice on forming an underground

organization.49 Transmovement groups' marginal position has reduced

the pressure to develop ideological visions with broad appeal (indeed,

members' collective identity may have been preserved by emphasizing

differences with dominant ideologies50). This may result in a sophisti-

cated ideological vision, but one too esoteric or radical for a potential

recruitment base. Even if not seen as subversive, their very longevity

may make them unappealing to a fledgling movement eager to distin-

guish itself from an older generation of activists.51

A second structure often dubbed a free space is indigenous to a com-

munity and initially is not formally oppositional. Indigenous groups

include Southern black churches before the emergence of mass insur-

gency, German Turner halls and anti-temperance societies in nineteenth-

century Chicago, and Kuwaiti mosques during Iraqi occupation.52

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

11

Discussions of these groups have focused on their political, social, and

economic isolation from dominant institutions and the density of their

associational ties. Strongly integrated networks facilitate recruitment

on the basis of pre-existing ties;53 dense horizontal ties and the lack of

ties to groups in power facilitate the development of an oppositional

frame. Thus Hirsch writes, "the lack of positive vertical ties - the lack

of social interaction with upper status groups - makes it more likely

that such groups can be successfully defined as the enemy, which makes

it easier to sustain commitment to revolutionary goals and tactics and

prevents movement participants from developing undue sympathy for

the opponent."54 Craig Calhoun argues similarly that "traditional

communities" have often proved potent revolutionary forces on account

of their distance from outsiders and strongly integrated networks.

These provide the communication resources, solidary incentives, and

commonality of interests necessary to develop a radical challenge.

Normally conservative, members of traditional communities may mo-

bilize when their "interests," that is, their families, friends, customary

crafts, and ways of life, are threatened by rapid social changes or when

such changes "put old goals within reach." 55 Their centrality to people's

daily lives equips indigenous groups to recruit a first wave of partic-

ipants, develop leaders, and formulate mobilizing frames in a familiar

idiom. However, as I noted above, they are not well positioned to

identify the extra-local political shifts and potential allies that provide

important resources for protest. The concentration of ties in indigenous

institutions may make it difficult to mobilize beyond the bounds of the

locality; hence the importance of formal movement organizations in

mass recruitment.56

A third structure often denoted by the term free space is the prefigurative

group created in ongoing movements. These are the "autonomous

zones" of European new social movements, the "women's only spaces"

of 1970s radical feminism, the "block clubs" created by tenant organ-

izers to mobilize an urban constituency, the alternative food co-ops,

health clinics, credit unions, and schools that flourished in the late

1960s and 1970s.57 Explicitly political and oppositional (although their

definition of "politics" may encompass issues usually dismissed as

cultural, personal, or private), they are formed in order to prefigure the

society the movement is seeking to build by modeling relationships that

differ from those characterizing mainstream society.58 Often that means

developing relations characterized by symmetry, that is, reciprocity in

power, influence, and attention.59 I say often, because prefiguration

may sometimes mean modeling relationships with the proper degree

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12

of deference and authority, not equality.60 My association of prefigura-

tion with symmetric ties simply reflects free space analysts' focus on

left-leaning rather than right-leaning movements (more on that be-

low).61 Prefigurative groups often restrict membership to foster new

interpersonal ties. Thus, by excluding men, women's only spaces

sought to foreground and strengthen the ties among women that were

not yet salient in their everyday lives.62 Since these structures are

created in movements that are already underway, they don't play a

role in identifying the political opportunities that precede mobilization.

However, they help to sustain members' commitment to the cause and

may prove launching pads for "spin-off" organizations or movements

based on new identities and associated claims.63 As a number of authors

have pointed out, prefigurative groups are difficult to sustain, not only

because the requirements of fully egalitarian decisionmaking are diffi-

cult to square with the demands of quick response to environmental

demands, but because in societies characterized by taken-for-granted

assumptions about class, race, gender, expertise, and authority, "social

inequalities can infect deliberations, even in the absence of any formal

exclusions" as Nancy Fraser maintains.64 On the other hand, if they

can provide services (healthcare, food, education) that successfully

compete with mainstream service providers, they may become enduring

indigenous institutions and may supply leaders and participants for

later mobilizations.65

Detailing the patterns of relations that make up each of these structures

and that position them in a multiorganizational field of authorities,

opponents, and allies provides clues to their resources and liabilities for

protest. Transmovement groups' generational, organizational, and geo-

graphic reach helps to explain both their capacity to nurture fledgling

organizations by making available financial, technical, and legal ad-

vice and their weaker capacity for mass recruitment. The density of

relations in indigenous groups affords incentives to participate even in

high-risk activism while the concentration of such ties impedes wide

mobilization. Prefigurative groups' insistence on symmetrical ties throws

into relief the asymmetries of conventional relations and model alter-

natives, but also undercuts the groups' prospects for survival. It seems

clear, then, that while physical settings are important to establish or

reaffirm social relationships, it is the relationships themselves rather

than the physical sites that are important in explaining their role in

mobilization.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

13

But there is more to it than that. Analyzing these structures apart from

the normative commitments, both explicit and implicit, that animate

them provides inadequate account of their roles in protest. The place

of culture is obvious in the case of prefigurative groups, where the

institutionalization of symmetric relations reflects beliefs about

equality and the proper relationship between means and ends in social

movements. But explicit normative commitments and taken for granted

cultural understandings are just as important to the other two struc-

tures. Not all groups with long-standing and extensive political ties

support new movements: the National Council of Churches, for exam-

ple, only began to assist civil rights and migrant farmworker activists

after the rise of a modernist ideology of social change activism.6 No

one sees the Boy Scouts as a movement halfway house, although this is

a group with extensive ties and, as a social organization, is removed

from mainstream American political institutions. Likewise, indigenous

groups' capacity to nurture opposition is often a function of institu-

tionalized normative principles, which permit religious, familial, and

educational groups some degree of autonomy from state interven-

tion.67 And dense ties are as likely to discourage collective action or

limit it to purely local targets as to generate broad insurgency. As

Roger Gould asks, "What aspect of a dispute over grazing rights with

a local landlord would suggest to the peasants of a pastoral village that

their conflict was a single instantiation of a broader struggle between

'the peasantry' and 'the nobility?' "68 The existence of an indigenous

structure (a church, a guild, a civic association) is not enough to

explain how threats, antagonisms, or opportunities come to be per-

ceived in terms of mobilizing identities and interests.

The problem with discussions of free spaces is not only, then, that their

conflation of transmovement, indigenous, and prefigurative structures

has obscured the different roles that each is likely to play in mobiliza-

tion. Despite their claim to integrate culture and structure, discussions

of free spaces have tended to reduce culture to structure. By attributing

alternative or oppositional cultural practices simply to the existence

of dense and isolated structural ties, free space arguments miss the

possibility that dense ties may not generate oppositional ideas and

identities, and that weak ties may. By attributing full-fledged insur-

gency to the political (structural) opportunities that make oppositional

cultures mobilizing, free space arguments miss the possibility that

people may use an oppositional culture to create political opportunities.

I discuss the latter first, drawing on some of the most sophisticated

accounts of free spaces to highlight problems common to many.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14

One: Culture and "structural" opportunities

In their discussion of what they call "havens," "liberated zones," "pre-

serves," and "'free' social spaces," Fantasia and Hirsch argue that

while subordinate groups are able to "question the rationalizing ideol-

ogies of the dominant order, develop alternative meanings, [and] iron

out their differences" in these settings, it is "the context of acute social

andpolitical crisis that provides the key fulcrum for the transformation

of traditional cultural forms" into overt opposition.69 And again, "we

would emphasize that the extent to which culture is transformed in

collective action depends not only on the availability of social and

spatial 'preserves' within which traditional forms may be collectively

re-negotiated but also, and more importantly, on a level of social

conflict that forces participants outside the daily round of everyday

activity."70 These formulations suggest that free spaces play only a

minimal role in igniting insurgency, since culture within the free space

is, if oppositional, then not mobilizing until the "crisis" that reorients

the meaning of traditional practices.7

Contrary to Fantasia and Hirsch, James Scott sees subordinated

groups, whether outside sequestered social sites or within them, as

unswayed by the ideological blandishments of the powerful. Rejecting

even a thin hegemony argument, which holds that people acquiesce to

their domination because they take it as inevitable (rather than as

right), Scott argues that what usually prevents utopian longings and

an "infrapolitics of dissent" from being translated into overt defiance

is simply the likelihood of severe repression. "Any relaxation in sur-

veillance and punishment, and foot-dragging threatens to become a

declared strike, folktales of oblique aggression threaten to become

face-to-face defiant contempt, millennial dreams threaten to become

revolutionary politics." 72 Indeed, "[a]s soon as the opportunity presents

itself," apparent passivity turns to rebellion.73 Powerless people don't

require free spaces to recognize the injustice of their situation. What

free spaces do provide is the opportunity to articulate safely "the asser-

tion, aggression, and hostility that is thwarted by the on-stage power

of the dominant," 74 to plot alternatives, and to test the limits of official

power. For Scott, like Fantasia and Hirsch, the hidden transcripts

developed in free spaces do not ignite overt protest. Rather, objective

political opportunities are created remote from the agency of the op-

pressed. The oppressed, however, are always alert to potential chinks

in the repressive armor of authorities and move quickly to take advant-

age of them.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

15

The problem with these accounts of mobilization is their privileging of

structural change outside the free space over the cultural framing that

takes place within it. Cultural challenge is effective only when social,

political, and economic structures have become unstable, that is, when

repression has been relaxed,75 when political realignments have cre-

ated a "structural potential" for mobilization,76 or when a structural

"crisis" has bankrupted old ideas and made people receptive to new

ones.77 But these formulations raise thorny questions. Aren't political

and economic structures themselves shaped by cultural traditions and

assumptions? And can't social movements contribute to destabilizing

the institutional logics that inform everyday life? As Gamson and

Meyer point out, differing political opportunity structures reflect not

just different political systems, for example limits on the executive

branch and a system of checks and balances, but also different public

conceptions of the proper scope and role of the state.78 "State policies

are not only technical solutions to material problems of control or

resource extraction," Friedland and Alford argue in the same vein.

"They are rooted in changing conceptions of what the state is, what it

can and should do."79 Such conceptions extend to state-makers and

managers who, like challengers, are suspended in webs of meaning.80

Whether elections "open" or "close" political opportunities surely has

to do with whether elections have historically been catalysts to collective

action and whether there exists an institutional "collective memory" of

state-targeted protest. Something as ostensibly non-cultural as a state's

repressive capacity reflects not only numbers of soldiers and guns but

the strength of constitutional provisions for their use and traditions of

military allegiance. In her discussion of protest policing, Donatella

della Porta observes that while the West German police "views itself

as a part of a normative order that accepts the rule of the law," the

Italian police "since the creation of the Italian state had been accus-

tomed to seeing itself as the longa manus of the executive power, and

thus put preservation of law and order before the control of crime."

These views in turn shaped the opportunities for different forms of

protest.81 Note that some of the above, for example, state officials'

ideological assumptions, may exercise only transient or weak influence

over a structure of political opportunities; others, for example, state

legitimacy, may have stronger effect, be less malleable, and still others,

say, conventions of political commemoration, may be somewhere in

between.82 Movements themselves can create political opportunities

by changing widespread beliefs.83 For example, a movement may be

responsible for lowering the level of state repression that is considered

legitimate and that can therefore be deployed against subsequent in-

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16

surgencies.84 A culture/structure dichotomy obscures the many instan-

ces in which people have seen opportunities where "objectively" there

were none.85

Scott seems to be making just this point - and retreating from the

sharp separation of structure (opportunities) and (mobilizing) culture

that he posits elsewhere - when he writes:

An objectivist view would ... have us assume that the determination of the

power of the dominant is a straightforward matter, rather like reading an

accurate pressure gauge. We have seen, however, that estimating the inten-

tions and power of the dominant is a social process of interpretation highly

infused with desires and fears. How else can we explain the numerous instan-

ces in which the smallest shards of evidence - a speech, a rumor, a natural

sign, a hint of reform - have been taken by slaves, untouchables, serfs, and

peasants as a sign that their emancipation is at hand or that their adversaries

are ready to capitulate?86

Scott goes on to pose the "central issue" as what Barrington Moore

calls "the conquest of inevitability." "So long as a structure of domi-

nation is viewed as inevitable and irreversible, then all 'rational' oppo-

sition will take the form of infrapolitics: resistance that avoids any

open declaration of its intention."87 But he has already acknowledged

that unobtrusive resistance has less potential for change than overt

defiance ("No matter how elaborate the hidden transcript may be-

come, it always remains a substitute for an act of assertion directly in

the face of power"88). And if what stands in the way of engaging in

such overt politics is a perception of the "inevitability" of the existing,

then isn't this precisely the "thin" theory of hegemony that he earlier

dismissed? Despite his claims to the contrary, Scott ends up shifting

between the objectivism he derides and a reliance on false conscious-

ness to explain people's failure to mobilize.

An alternative, following Sewell, is to conceptualize structures as cul-

tural schemas invested with and sustaining resources, in other words,

schemas that reflect and reproduce unevenly distributed power.89 This

helps to explain structures' durability and their transformation. It is

not that they bring about their own mutation - not that they have

agency - but that they are invested with meanings that afford resources

for insurgents challenging them. People can "transpose schemas" from

one setting to another, can turn the worker solidarity fostered by

capitalist production, for example, into a force for radical action.

Sewell's scheme gives people more power to capitalize on minimal

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

17

opportunities by framing conditions in a way that makes collective

action possible or necessary. Unlike free space analyses' tendency to

dichotomize culture and structure (with culture inside the free space

and structure outside it), it reveals overlooked resources for mobiliza-

tion.

It also reveals, contrarily, overlooked cultural obstacles to protest.

Activists' vocabularies of protest are shaped and limited by ostensibly

non-cultural political, economic, and legal structures. For example, to

understand the currency of an "individual rights" frame, as compared

to a "human rights" frame or a class-based frame, one would have to

understand the legal and political traditions, systems, and rules through

which those terms have become meaningful. Tarrow notes that "the

French labor movement embraced an associational 'vocabulary' that

reflected the loi le Chapelier, while American movements developed a

vocabulary of 'rights' that reflected the importance of the law in Amer-

ican institutions and practice."90 Popular conceptions of "equality,"

"personhood," and "problem" are shaped by dominant legal institu-

tions.91 Neo-institutionalist theories of organization should alert us

to the institutional shaping of movement forms, and indeed, to the

historical and cultural preeminence of the organization as a means of

protest.92

To get at these resources and constraints requires that we abandon a

set of binary oppositions that have underpinned and undermined recent

efforts to integrate culture into accounts of mobilization, including but

extending beyond discussions of free spaces. Thus "cultural," "subjec-

tive," and "malleable" have been opposed to "structural," "objective,"

and "durable." Free space discussions have rendered that set of opposi-

tions spatial: culture is restricted to the free space, structure to relations

outside it.93 As a result, they have underestimated continuities between

the two, have ignored the cultural traditions, institutional memories,

and political taboos that structure politics and that can be used by

insurgents to strategic effect, and have ignored how cultural under-

standings of organization, rationality, legality, and agency constrain

insurgents' strategic decisionmaking. In other words, discussions of free

spaces have simultaneously underestimated the durability of culture

and the malleability of structure.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18

Two: Culture and "structural" ties

In his review of Scott's Domination and the Arts of Resistance, Charles

Tilly asks an interesting question: Why is there only one hidden tran-

script for each subordinated group? Why not as many transcripts as

subordinated individuals? Indeed, "why not ten, twenty, a hundred as

many discourses as subordinates?" Scott's argument "requires that

each subordinated population produce a unitary and shared hidden

transcript.... Don't subordinates ever resist the hidden transcript?

Scott supplies no answers."94

Actually, Scott does provide an answer, but a misleading one. "Social

spaces of relative autonomy do not merely provide a neutral medium

within which practical and discursive negations may grow. As domains

of power relations in their own right, they serve to discipline as well as

to formulate patterns of resistance."95 And again: "the hidden transcript

is a social product and hence a result of power relations among subordi-

nates."96 Yet when he describes the process by which a single, coherent

transcript is pieced together from multiple negations, the power relations

he just identified drop out. "In this hypothetical progression from 'raw'

anger to what we might call 'cooked' indignation, sentiments that are

idiosyncratic, unrepresentative, or have only weak resonance within

the group are likely to be selected against or censored.... The essential

point is that a resistant subculture or countermores among subordi-

nates is necessarily a product of mutuality." 97 In other words, the oppo-

sitional frame that is developed within the free space is uninfluenced by

relations of power, authority, and deference within the group.

What that misses, of course, are the ways in which densely-structured

relations within dominated groups foreclose as well as enable certain

kinds of challenge depending on the normative content of those ties.

By making oppositional identities and meanings a function of the

existence of dense ties within isolated networks, analyses of free spaces

have minimized culture's analytically independent role within free

spaces as well as outside them. By contrast, I argue that culture oper-

ates in the formal ideologies enacted in the community institutions

labeled free spaces - the church, the union, the civic association - and

in the behavioral expectations associated with, indeed constituting, ties

of kinship, neighborhood, and contract.

To illustrate, I turn to Eric Hirsch's rich account of working-class

mobilization in nineteenth-century Chicago.98 Hirsch argues that Ger-

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19

man workers launched a revolutionary movement while Irish and

Anglo-American workers did not in part because Germans possessed

"havens" or "free social spaces." The "structural isolation from ruling

groups [of these settings] ... allowed subordinate groups to develop

innovative ideas about the nature of the system, to identify those

responsible for the subordinate groups' plight, and to discover what

action was needed to resolve their common problems."99 But there is

no reason that sheer isolation will guarantee the replacement of a

dominant ideology with an action-mobilizing injustice frame (and

physical proximity, at least, has not prevented people from penetrating

the ideologies propounded by those in power, as Judith Rollins showed

in her study of domestic workers0l?). In fact, Hirsch's historical ac-

count reveals that whereas German workers' exposure to anarchist and

socialist ideas in Turner halls, anti-temperance meetings, and anar-

chist-sponsored picnics made them receptive to a revolutionary inter-

pretation of their exploitation, exploited Irish workers tended to accept

an Anglo-American ideology of individual success and accordingly to

reject the idea of working-class mobilization. Irish workers had havens

too, most importantly the Catholic Church, but the Church's animosity

to radical thought, along with Irish nationalist organizations' focus on

the Irish/British conflict overseas, led Irish workers to blame their

troubles on their lack of skills, and to attribute their lack of skills to

Britain's underdevelopment of Ireland.101 Hirsch's historical analysis,

contrary to his theoretical brief, suggests that the mobilizing power of

havens lies not just in their structural isolation but in their specific

cultural content. Or, better put, that it was the combination of dense

networks and the availability of a radical cultural idiom that was

responsible for the revolutionary character of German mobilization.

The story that Hirsch tells (as distinct from the way he theorizes it), is

not exceptional. Other accounts have shown how insurgency is shaped

by the institutions within which it develops. For example, Doug Rossi-

now characterizes as a "free space" the Christian Faith and Life Com-

munity (CFLC) on the University of Texas campus in the late 1950s, a

group that produced leading activists of the white student left. "It was a

'free space' where, as one student said, he felt the 'freedom to talk

about my questions' - questions of self, of God and of life.... [It]

prepared students to take political action in defiance of established

power."102 Yet, Rossinow shows that what motivated members to plan

sit-ins and pickets against segregated facilities was the Christian exis-

tentialism they absorbed in the CFLC, and particularly its emphasis on

achieving a spiritual "breakthrough" via political engagement rather

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20

than personal reflection.103 It was not just the "safe haven"104 provided

by the CFLC, but the particular cultural frames institutionalized within

it that inspired the students. Similarly, Mary Ann Tetreault shows that

the mosque played a crucial role in Kuwaiti opposition to Iraqi occu-

pation not just because it was one of the few associations that was not

repressed, but because of its long-standing and "morally unassailable"

authority to challenge the state.105 The importance of the cultural

frames associated with particular institutions is obscured by a view of

free spaces as defined solely by social distance between powerful and

powerless. People's physical or social separation from mainstream

institutions doesn't guarantee the emergence of a mobilizing collective

action frame. What is crucial is the set of beliefs, values, and symbols

institutionalized in a particular setting.

It would be a mistake, however, to see culture only as the ideologies

enacted in community institutions rather than also as the basis for the

very ties that make up the community.106 With respect to free space

analysts' claim that dense and isolated networks facilitate protest, it is

just as likely that, depending on the circumstances, such networks may

impede protest. This is partly because the absence of ties to outsiders

may lead aggrieved people to interpret threats and conflicts in purely

local terms, as Roger Gould points out, rather than in terms of the

broader identities and ideologies that are necessary to mass mobiliza-

tion.107 Gould argues that the development of mobilizing identities

requires significant interaction across communities, in other words,

that social ties determine the scale as well as content of collective

identities. But the same ties may, depending on the circumstances,

favor very different or contradictory behaviors. Neighborhood ties may

promote competition rather than mutuality.'08 Business ties may pro-

mote solidarity but also deference. As Allan Silver shows, friendship in

eighteenth-century Europe carried different behavioral prescriptions

than it does today.109 The point is that the behaviors expected of and

imputed to patterned relations are multiple and variable."? Thus,

strong ties may impede mobilization."' And weak ties may facilitate

it, not only because they provide access to people and resources out-

side the community, but because potential insurgents may grant

"known strangers" the authority to challenge the bonds of authority

and deference within the community that have kept people from overt

defiance.

My point, then, is that while it makes sense to pay attention to the

structure of relationships that supply resources for various mobiliza-

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

21

tion tasks, we can strengthen that investigation in several ways: by

recognizing that ties can impede mobilization as well as foster it; by

recognizing a greater range of network dynamics, that is, the role of

weak ties, network holes, conflicts, and intersections;112 and by identi-

fying the fuller range of behavioral prescriptions associated with par-

ticular ties. In the following, I don't attempt the full investigation I

have in mind, but do review two cases that are frequently cited as free

spaces: the black church for the civil rights movement, and the student

wing of the civil rights movement for radical feminism."13 Rather than

characterizing each one as a space in which the constraints exercised

by structure were somehow suspended, I identify behavioral expect-

ations that constrained mobilization by African-Americans in South-

ern communities and by feminists within the civil rights movement,

and then show how they were overcome. In each case, I find that

network intersections generated mobilizing identities, but not only be-

cause weak ties to other networks (in the first case the national civil

rights movement, in the other Northern left circles) provided material

or informational resources that were previously lacking. Rather, their

social distance and social status endowed local members of those

networks with the power to challenge the relations of authority and

deference that operated among members of the aggrieved group.

Without detracting from the vitally important role of Southern black

churches in nurturing and sustaining Southern civil rights protest,

evidence suggests that in many Southern communities, particularly

rural ones, black ministers were not the shock troops of the struggle.

Field reports by student organizers in the early 1960s make clear that

many ministers were reluctant converts to the cause.114 Ministers'

timidity often stemmed from their financial dependence on whites:

whereas in Southern cities, ministers' livelihoods came entirely from

their parishioners, in rural areas most were forced to work part time

for whites and were therefore more vulnerable to economic reprisals.

In addition, some church leaders enjoyed positions of brokerage with

powerful whites, and were compensated in some fashion for serving as

advocates of only moderate reform. These stakes were threatened by

the development of new leaders, whether student organizers or black

residents.

"Outsiders" proved important in overcoming those barriers to radical

action. The resources possessed by student organizers who moved into

rural areas in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia in the early 1960s are

not readily apparent. With neither federal backing nor the capacity to

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22

furnish physical or financial protection, organizers could offer resi-

dents little in the way of material incentive to participate. Their arrival

was often met with stepped-up white violence against black residents.

Yet, organizers were seen as representatives of a national movement

and were often called "freedom riders" long after the freedom rides

had ended. Perhaps some residents believed that the organizers' pres-

ence signaled the government's willingness to intervene, but my review

of field reports, testimony at mass meetings, and interviews with for-

mer organizers suggests that other rationales were operating. The

young organizers were putting their lives on the line, were willing to

die for black Mississippians' freedom, locals often reminded each other.

How could they not participate? The rationale was one of obligation

more than opportunity, and it was the organizers' outsider status, the

distance they came, that authorized their calls to participate.115

Georg Simmel described the "stranger" as combining "distance and

nearness, indifference and involvement." Strangers "are not really con-

ceived as individuals," but this does not mean that they are marginal or

powerless. To the contrary, Simmel observed, the stranger often enjoys

a position of influence by virtue of his "free[dom] from entanglement"

in existing interests and cleavages.116 This seems to have been the case

with Southern student organizers. Their intimate involvement in the

life of Mississippi black communities made them trustworthy, while

their outsider status enabled them to challenge the relations of defer-

ence that impeded militant collective action. Former SNCC activist

Hollis Watkins remembers that several organizers had begun seminary

training and others, like Watkins himself, were well-versed in scripture

and skilled orators. Some ministers may have come around to support-

ing the movement, Watkins suspects, because they believed that the

SNCC organizers were ministers, whose popularity with the local

people made them a threat to their jobs. This is an example of how the

very weakness of informational ties facilitated mobilization.117 A view of

free spaces as untrammeled by relations of power and authority misses

in this case both the constraints on mobilization and the dynamics by

which they were overcome. Categorical classification of actors as

black, white, or middle class would miss the networks crosscutting

those categories, which proved more salient to people's decision to

participate, or to oppose participation, than categorical "interests."

Southern ministers who were initially wary often did come around to

supporting and, indeed, leading the struggle. It seems that the most

successful organizers managed to persuade, cajole, or help residents to

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

23

push traditional leaders into an active role rather than circumventing

them altogether.118 Thus a Holly Springs organizer reported happily in

1963, "The image of students knocking on doors, the fact of their

speaking at churches on Sundays, and the threat of demonstration

have served to build respect for them and has challenged the local

ministers no end. They see this and are beginning to work to try to

build their images and redeem themselves.""119 Outsiders didn't em-

power a powerless group, or enlighten the falsely conscious, but they

did undermine the structured relations within the group that channeled

resistance in a conservative direction.120

Contrary to historical accounts - Sara Evans's (1979) seminal piece and

the host that have followed her121 - it seems that outsiders, or weak-

tied individuals, were also crucial in the emergence of a feminist chal-

lenge within SNCC. In November 1964, a position paper on sexism in

the movement was floated anonymously at a SNCC staff retreat. Evans

attributed the paper to two white SNCC veterans: Casey Hayden, who

had been involved with SNCC since its founding in 1960, and Mary

King, who joined in 1962. On Evans's account, Hayden and King's

conversations with other women about their second-class status in the

movement and discussions of the writings of de Beauvoir, Lessing, and

Friedan culminated in their decision to bring up the issue with the

SNCC staff. The paper they wrote documented a range of sexist prac-

tices - women relegated to minute-taking duties, rarely given projects

to direct, never made SNCC spokespeople - and called on the group to

extend its egalitarian commitment to women. For Evans and subse-

quent chroniclers, the fact that the memo was written by longtime

SNCCers suggested that in spite of their circumscribed role as women,

Hayden and King had the freedom to explore this "new" source of

oppression, to toy with unconventional ideas and experiment with

new roles. It suggested that SNCC was indeed a kind of cultural

laboratory for radical ideas, a "free space." A year after the first memo

was met with the laughter and derision they had anticipated, Evans

goes on, King and Hayden collaborated on a second memo, directed to

black and white women active in the civil rights and New Left move-

ments. Its effect, by all accounts, was galvanizing, and spurred women

to build the networks and consciousness-raising groups that would

eventually explode into radical feminism.

In fact, new testimony suggests that a larger group, including several

Northern white women who had only recently joined SNCC, wrote the

first anonymous memo in November 1964.122 These women occupied a

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24

curious position: they became part of SNCC's inner circle almost upon

their arrival in Mississippi because SNCC was so shorthanded on the

eve of the massive summer project it was planning, but they lacked the

bonds of long friendship that united veteran members of the group.

Active in other movements here and abroad, they brought a "Northern"

aggressiveness that enabled them to defy not only the group loyalty that

made criticism difficult, but also the norms of deference that struc-

tured white women's relations to the mainly black men who headed

SNCC. Taking meeting minutes, not seeking the higher status job of

field organizer, not competing for the public limelight; white women

veterans understood these as choices, made because they were unwill-

ing to endanger black residents by serving as field organizers, but also

because they saw the movement as properly led by black men. It was

easier for women who were longtime members of the group to see an

auxiliary role as consonant with the group's radically egalitarian ethos.

And it was easier for women whose ties to the close-knit SNCC cadre

were weaker to name that role as inequality. Again, network overlaps

not only provided access to new sources of information and new

procedural norms, but gave license to contest long-standing bonds of

friendship and shared political commitment.

Views of indigenous structures as providing only resources for mobi-

lization and not constraints preclude analysis of how mobilizing iden-

tities and interests are shaped by the culture-structures within which

grievances are framed, and by the networks that provide and limit

access to power, information, and authority. Rather than seeing a

single subordinate group or community, with a single set of interests,

free space, and "hidden transcript," 123 we should examine the multiple

networks, some extending beyond the bounds of the locality, which

generate distinct, often conflicting, interests and identities. Thus, in

the case of Southern civil rights organizing, we see how the connec-

tions of some black ministers to white elites discouraged their adopting

a militant stance, this in spite of their prior commitment to reform.

A second important line of inquiry would explore the effects of differ-

ent kinds and strengths of social relations.124 Rather than assuming

that protest requires dense ties, we should investigate where and when

dense ties constrain action and "weak" ones facilitate it. The latter

point is reflected in the role of "outsiders" in both cases of mobiliza-

tion that I described. Mississippi civil rights workers' combination of

intimacy and distance gave them the capacity to defy structured rela-

tions within black communities, this in spite of their lack of access to

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

25

material or political institutional resources. Similarly, the white women

who were fairly new to SNCC when they catalyzed a feminist challenge

were in overlapping networks: a Southern black movement and a

Northern white one. Their marginal position in the former, with access

to the inner core of decisionmakers but without close bonds to them,

made it easier, and more acceptable, for them to refuse the more defer-

ential role played by white women veterans. These examples also show

the intersection of the cultural and structural dimensions of networks.

Outsiders' scope of action had to do not with the actual resources they

brought to bear, but with those imputed to them, and with cultural

understandings of intimacy and remoteness, of the boundaries of the

group, and of the range of the sayable.

Conclusion

One of the chief analytic payoffs of the free space concept was to have

been its capacity to integrate culture into structuralist models of collec-

tive action. I argue that, so far, such analyses have not taken adequate

measure of the multiple and contrary dimensions of the culture/struc-

ture relationship. Fuller specification of that relationship alerts us both

to the greater capacities of cultural challenge to destabilize institutional

arrangements and, at the same time, to the obstacles that stand between

cultural challenge and full-fledged mobilization.

Rather than continue to rely on the ambiguous "free spaces" concept, I

have argued that we should explore how the form and substance of

associational ties in different contexts shape the emergence of mobi-

lizing identities. Physical gathering places may build on those ties by

demonstrating the co-presence of others, thus showing people that

issues they thought taboo can be discussed, and strengthening collec-

tive identity by providing tangible evidence of the existence of a group.

However, it is the character of the ties that are established or reinforced

in those settings, rather than the physical space itself, that the free

space concept has sometimes successfully captured. Networks predat-

ing movements, as resource mobilization theorists have long noted, are

critical in supplying the personnel, resources, and tactical expertise

necessary to mobilization.125 They are also important in fostering and

impeding the very identities and interests on the basis of which mobi-

lization is mounted.

This content downloaded from

201.163.9.162 on Tue, 01 Nov 2022 22:17:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26

To begin to illuminate those dynamics, I have disaggregated the struc-

tures that are more and less equipped to identify opportunities, recruit

participants, develop leaders, generate collective action frames, and

fashion new identities. The typology of transmovement, indigenous,

and prefigurative structures that I have introduced is preliminary but it

should alert us to the different kinds of resources and constraints levied

by different kinds of ties, respectively, extensive, dense, and symmet-

rical. In analyzing indigenous networks' role in developing mobilizing

identities, where the need for something like the free space concept is

most apparent, I have argued for attention to the ways in which pre-

existing network ties militate against the formation of mobilizing iden-

tities, and the dynamics by which such constraints are surmounted.

One such dynamic is the network intersections that provide an ag-

grieved population new access not only to physical, financial, and

communicative resources, but also to people whose only weak ties and

consequent social distance and status enable them to challenge existing

relations of deference. There are other such dynamics. Specifying them

enables us to understand the conditions in which cultural challenge

explodes structured relations, without reducing those conditions to

structural voids.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by a Columbia University Social Sciences

Faculty Grant. I presented a version of this article at the American

Sociological Association Meeting in Toronto in August 1997. For val-

uable comments on previous drafts, my thanks to William Gamson,

Todd Gitlin, Stephen Hart, James Jasper, Paul Lichterman, David

Meyer, Kelly Moore, John Skrentny, Marc Steinberg, Charles Tilly,

and the Editors of Theory and Society. Thanks also to Linda Catalano