Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Class 3 4

Uploaded by

GAURAV BHARDWAJOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Class 3 4

Uploaded by

GAURAV BHARDWAJCopyright:

Available Formats

Trade in Competitive Markets

• Consider trade in perfectly competitive markets.

• Each consumer is a price taker trying to maximize her own utility

given p1, p2 and her own endowment.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

• So given p1 and p2, consumer A’s net demands for commodities 1

and 2 are 𝑥1∗𝐴 − 𝜔1𝐴 and 𝑥2∗𝐴 − 𝜔2𝐴 .

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

• So given p1 and p2, consumer B’s net demands for commodities 1

and 2 are 𝑥1∗𝐵 − 𝜔1𝐵 and 𝑥2∗𝐵 −𝜔2𝐵 .

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Gross vs. Net Demand

• The gross demand of agent A for good 1, say, is the total amount of good 1 that

he wants at the going prices.

• The net demand of agent A for good 1 is the difference between this total

demand and the initial endowment of good 1 that agent A holds.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

• A general equilibrium occurs when prices p1 and p2 cause both the

markets for commodities 1 and 2 to clear. In other words,

and

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Copyright © 2019 Hal R. Varian

Trade in Competitive Markets

• For arbitrary prices (p1, p2) there is no guarantee that supply will equal

demand—in either sense of demand.

• In terms of net demand, this means that the amount that A wants to buy (or

sell) will not necessarily equal the amount that B wants to sell (or buy)

• In terms of gross demand, this means that the total amount that the two agents

want hold of the goods is not equal to the total amount of that goods available

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

• This case the market is in disequilibrium

• In such a situation, it is natural to suppose that the to change the prices of the

goods

• If there is excess demand for one of the goods, the price of that good will rise

• If there is excess supply for one of the goods, its price will fall

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Copyright © 2019 Hal R. Varian

Trade in Competitive Markets

• At the new prices p1 and p2 both markets clear.

• It is called a market equilibrium, a competitive equilibrium, or a

Walrasian equilibrium

• Trading in competitive markets achieves a particular Pareto optimal

allocation of the endowments.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

• If each agent is choosing the best bundle that he can afford, then his marginal

rate of substitution between the two goods must be equal to the ratio of the

prices

• But if all consumers are facing the same prices, then all consumers will have to

have the same marginal rate of substitution between each of the two goods

• An equilibrium has the property that each agent’s indifference curve is tangent to

his budget line

• But since each agent’s budget line has the slope −p1/p2, this means that the two

agents’ indifference curves must be tangent to each other.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Trade in Competitive Markets

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Copyright © 2019 Hal R. Varian

First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

• Given that consumers’ preferences are well behaved, trading in

perfectly competitive markets implements a Pareto optimal

allocation of the economy’s endowment.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

• Pareto optimal allocation (i.e., any point on the contract curve) can

be achieved by trading in competitive markets provided that

endowments are first appropriately rearranged among the

consumers.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

• Given that consumers’ preferences are well behaved,

for any Pareto optimal allocation there are prices and an allocation of

the total endowment that makes the Pareto optimal allocation

implementable by trading in competitive markets.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Walras’s Law

• Walras’s law is an identity, i.e., a statement that is true for any positive prices

(p1, p2), whether these are equilibrium prices or not.

• Every consumer’s preferences are well behaved so, for any positive prices (p1,

p2), each consumer spends all of his budget.

For consumer

For consumer

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Walras’s Law

Summing

which can be rearranged to

This says that the summed market value of excess demands is zero for any positive

prices p1 and p2.This is Walras’s law.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Implications of Walras’s Law

Two key implications of Walras’s law for a two-commodity exchange economy:

• If one market is in equilibrium then the other market must also be in

equilibrium.

• An excess supply in one market implies an excess demand in the other market.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

Exchange Economies

• Pure exchange economies involve no production, only endowments,

so there is no description of how resources are converted to

consumables.

• General equilibrium: all markets clear simultaneously.

• Both the first and second fundamental theorems of welfare

economics hold true.

• Now we add input markets and output markets and describe firms’

technologies.

© Dr. Abhishek Naresh

Assistant Professor

(CQEDS)

BIT Mesra

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Analysis of Electric Machinery Krause Manual Solution PDFDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Electric Machinery Krause Manual Solution PDFKuldeep25% (8)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- RTDM Admin Guide PDFDocument498 pagesRTDM Admin Guide PDFtemp100% (2)

- Mark Garside Resume May 2014Document3 pagesMark Garside Resume May 2014api-199955558No ratings yet

- Working With Difficult People Online WorksheetDocument4 pagesWorking With Difficult People Online WorksheetHugh Fox IIINo ratings yet

- RSA - Brand - Guidelines - 2019 2Document79 pagesRSA - Brand - Guidelines - 2019 2Gigi's DelightNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Class 1 2Document22 pagesModule 4 Class 1 2GAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Macro Module 1 CompleteDocument93 pagesMacro Module 1 CompleteGAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Class 3 4 5 6Document57 pagesClass 3 4 5 6GAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Is LM ModelDocument92 pagesIs LM ModelGAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Class 1 2Document35 pagesClass 1 2GAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Maths 2 Book Linear Algebra (All The Chapters)Document240 pagesMaths 2 Book Linear Algebra (All The Chapters)GAURAV BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Aptitude Number System PDFDocument5 pagesAptitude Number System PDFharieswaranNo ratings yet

- OZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1Document16 pagesOZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1aryan9411No ratings yet

- Traveling Salesman ProblemDocument11 pagesTraveling Salesman ProblemdeardestinyNo ratings yet

- Waterstop TechnologyDocument69 pagesWaterstop TechnologygertjaniNo ratings yet

- Mixed Up MonstersDocument33 pagesMixed Up MonstersjaneNo ratings yet

- Huawei R4815N1 DatasheetDocument2 pagesHuawei R4815N1 DatasheetBysNo ratings yet

- Manual s10 PDFDocument402 pagesManual s10 PDFLibros18No ratings yet

- Objective & Scope of ProjectDocument8 pagesObjective & Scope of ProjectPraveen SehgalNo ratings yet

- Theories of International InvestmentDocument2 pagesTheories of International InvestmentSamish DhakalNo ratings yet

- Sam Media Recruitment QuestionnaireDocument17 pagesSam Media Recruitment Questionnairechek taiNo ratings yet

- FAMOUS PP Past TenseDocument21 pagesFAMOUS PP Past Tenseme me kyawNo ratings yet

- Homework 1 W13 SolutionDocument5 pagesHomework 1 W13 SolutionSuzuhara EmiriNo ratings yet

- DarcDocument9 pagesDarcJunior BermudezNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Is Descriptive, Not Prescriptive.: Prescriptive Grammar. Prescriptive Rules Tell You HowDocument2 pagesLinguistics Is Descriptive, Not Prescriptive.: Prescriptive Grammar. Prescriptive Rules Tell You HowMonette Rivera Villanueva100% (1)

- WL-80 FTCDocument5 pagesWL-80 FTCMr.Thawatchai hansuwanNo ratings yet

- C C C C: "P P P P PDocument25 pagesC C C C: "P P P P PShalu Dua KatyalNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Students' Oral Communication in English ClassDocument10 pagesAssessment of Students' Oral Communication in English ClassKeebeek S ArbasNo ratings yet

- B122 - Tma03Document7 pagesB122 - Tma03Martin SantambrogioNo ratings yet

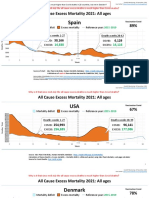

- Countries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021Document21 pagesCountries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021robaksNo ratings yet

- 04 - Fetch Decode Execute Cycle PDFDocument3 pages04 - Fetch Decode Execute Cycle PDFShaun HaxaelNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 ComprogDocument25 pagesLesson 6 ComprogmarkvillaplazaNo ratings yet

- Ron Kangas - IoanDocument11 pagesRon Kangas - IoanBogdan SoptereanNo ratings yet

- Evaluation TemplateDocument3 pagesEvaluation Templateapi-308795752No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDocument63 pagesChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNo ratings yet

- School of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1Document2 pagesSchool of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1STEM Education Vung TauNo ratings yet