Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How and Why To Change Your Taste Buds Over Time

Uploaded by

Liza GeorgeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How and Why To Change Your Taste Buds Over Time

Uploaded by

Liza GeorgeCopyright:

Available Formats

JUNE 30, 2016 BY EDIBLE COMMUNITIES

How and Why Your

Taste Buds Change

Over Time

Think about your favorite food. No, really think

about it. Close your eyes and think through the

whole process of anticipating, picking up, biting

down, chewing, tasting and swallowing it. Pretty

great, right?

Now think about your favorite food from

childhood. Is it the same? If not, how is it different

from your current favorite?

Now think of your least favorite food. Something

you can’t even stand to bring near your lips

because it’s so repulsive. Has that changed since

childhood? Any chance your current

favorite was your least favorite when you were

small?

Taste is such an intricate sensory experience—

one we perhaps don’t pay enough attention to,

considering how much it can transform over a

lifetime.

If you’ve recently converted to the Brussels

sprouts club after hating them most of your life, or

suddenly find yourself enjoying red peppers and

have no idea why, read on for a possible

explanation.

The physiology of taste

Taste, while experienced most pronouncedly in

the mouth, is the product of activity happening in

the sensors and cells of the physical body,

neurochemical activation, and memory, and it

depends greatly on our sense of smell.

There are five basic categories of taste: sweet,

salty, bitter, sour, and umami (otherwise known

as savory). Taste buds are the hardworking

receptors that communicate to our brain what

we’ve just placed on our tongues. They identify

specific chemicals in foods, then analyze the

overall profile, and send signals to the brain

that are translated as “sweet,” “salty,” etc.

It’s worth noting that flavor and taste are not the

same things. Sugar, a taste, and strawberry, a

flavor, are detected using different sensory

systems. Taste is experienced via the gustatory

(“taste”) receptors, the taste buds; meanwhile,

flavor is experienced through the olfactory

(“smell”) receptors. Having a compromised sense

of smell can impact your experience of a food.

You may still experience sweetness when drinking

the juice from the strawberry, but you might find

it more difficult to identify that it came from a

strawberry.

While the majority of our taste buds are located in

the bumps on our tongues, there are

also receptors on the roof of the mouth, on the

epiglottis and in the throat. They all work as a

team to send signals to the digestive system to

help the body use ingested nutrients most

effectively.

The body has evolved to identify each of these to

ensure adequate ingestion of a range of foods and

nutrients. Recent studies of the biochemistry of

taste have revealed that a separate receptor exists

to identify glutamate, an amino acid present in

proteins, which gives food a strong umami taste.

The study suggests that this receptor may have

evolved to ensure humans seek out and ingest

enough protein. Similarly, salty foods signal the

body that they contain sodium, an essential

nutrient for survival that can be difficult to find in

nature.

The average person has 10,000 taste buds at birth,

which are gathered in the papillae (little bumps)

on the tongue. Each papilla can have 1 to

700 taste buds, with each bud containing 50-80

specialized cells that work in concert to identify

tastes.

A supertaster, or someone who is extra sensitive

to subtle tastes and chemical combinations,

might have twice as many taste buds, while

below-average tasters may have just 5,000. The

combination and activation of taste buds and

their individual specialized cells also varies from

person to person, and affects the intensity of taste

one experiences.

Think back again on your preferences from

childhood. Did you tend to gravitate towards

sugary, creamy, salty, or generally non-vegetable

foods? You’re not alone. As children, we are super

sensitive to taste for two reasons: it helps us avoid

potential toxins, which is why dark green leafy

veggies taste extra bitter, and it helps us be finely

attuned to sugar, which we’ll express a strong

preference for. As in fruit, sweetness signals the

body that a food is likely to be high in nutrients

and energy, which the human child is evolved to

seek out to increase their chances of survival. For

the same reasons, children also have a

heightened sense of smell.

So is taste all about

genetics?

While many taste preferences

are genetically determined, such as those having

to do with how many buds you have or which

ones are activated in concert, most are based on

experience and culture. The shaping of taste

preferences begins in the womb and continues

throughout the rest of our lives, based largely on

what we’re exposed to and how we associate with

those early food experiences.

Think of the young kids you know and how they

are fed at home. The kids eating green veggies

and tofu like green veggies and tofu; those being

fed sugary cereal and Cheetos will prefer those.

The same goes for culturally specific spices like

coriander, cumin, and Chinese Five Spice.

The experience and

development of taste

For almost any new food, especially those with

unique or complex combinations of tastes, there

is a window of waiting before the body learns to

accept it. There is a biological imperative that

explains this “waiting period of acquisition.”

Basically, this is your chance to assess a food and

rule out intolerance, allergy or toxins. When

coupled with emotional acceptability (the

food makes us feel good), situational

acceptability (the food is experienced in a

situation that feels enjoyable or safe), and

physiological acceptability (the food did not

cause digestive upset or an allergic reaction), we

can learn to appreciate a food.

What changes our

sensation of taste with

time?

Remember those taste buds mentioned above,

the ones that fire in groups and in certain

combinations to prompt the experience of certain

tastes or flavors? There are a number of things

that happen to them as we age.

Bye bye, taste buds

Simply put, our taste buds die off. Hold on. It’s

less extreme than it sounds. Every two weeks or

so, our taste buds naturally expire and regenerate

like any other cell in the body. Around 40 years of

age, this process slows down, so while the buds

continue to die off, fewer grow back. Fewer taste

buds mean blander taste, and a different

combination of activated cells when we

experience a food. A “combination activation”

that used to taste delicious might not be so great

in its new, blander activation and vice versa. As

your remaining receptors reorganize to interpret a

taste, the subtle shift in how they signal for, say,

mushrooms might suddenly taste fantastic.

Bye bye, olfaction

Our sense of smell decreases as we age. In fact,

olfaction is the sense most affected by aging. This,

too, changes how we interpret a food and

whether or not we like it. It might mean we start

to gravitate towards stronger, more savory tastes,

as these will be more easily perceived and less

likely to register as bland.

The effect of hormones

Perhaps during no other time of life than

pregnancy are changes in taste preference most

notable—and we don’t just mean pickles and ice

cream. Studies have shown that pregnant women

have a decreased ability to taste salt in food. In

fact, they preferred foods with a significantly

higher salt content than non-pregnant women.

These studies suggested that the body has a

specific mechanism to increase salt intake during

pregnancy. If this is the case, other hormonal

fluctuations or changes in the body’s balance

might change taste, too.

The effect of stress

You probably already know that stress interrupts a

variety of bodily functions, including some that

influence taste. For this reason, it can also play a

role in shaping our short- and long-term

preferences. Stress can cause nutritional

deficiencies, which may cause a change in taste

to encourage the intake of specific foods. It can

alter hormone production and balance (as

above), and also interfere with sleep and cellular

regeneration, which play into how we experience

food. Notice if your taste preferences and cravings

change during stressful times.

The impact of what you’re

already eating

Because what we eat on a regular basis shapes

our taste preferences, we can find ourselves less

likely to prefer plain vegetables or unseasoned

salads. Why? The standard American diet is

packed with processed foods, where sugar, salt,

and oil abound. Excess consumption of these

foods can alter the body’s preference, raising our

threshold for tastiness. If we eat tons of salt, we

need more salt the next time to approximate the

same experience. We see this in kids, in particular.

What brain would opt for kale when its most

recent experience of Fruity-Cocoa-O’s was so

(artificially) delicious? The brain will turn down

the kale and elicit cravings for the more intense,

pleasurable taste instead.

How to retrain your palate

What we prefer early on and what we come to

prefer later in life will vary by person, experience,

and palate. But we won’t know how we’ve

changed if we don’t try new foods. The good news

is that we can train our palate to like

what we would like it to, especially if we have an

external motivator to try it, like the cute person

who keeps asking you to go for sushi even

though you can’t stand fish.

As we age, we’re more likely to

consciously try new foods with the intention of

enjoying them, as food and enjoyment become

more a matter of mind and memory than

physiological experience (which might explain

your childlike friend who still refuses to eat salad).

According to the Monell Chemical Senses Center,

We

theuse cookiespredictor

biggest to ensure that we givesomething

of liking you the bestis

experience

not so

on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume

much sensitivity to taste than motivation to like it.

that you are happy with it.

OK

For instance, think back to being eight years old

and hating coffee. The smell, the flavor, the very

sound of the can of grounds being opened—

pretty gross, right? This is one of those flavors, not

dissimilar to bitter leafy greens or pungent red

onions, that is only liked with repeated

consumption. Usually, to begin enjoying these,

we need to temper them with milk and sugar (or

brown sugar and butter or salsa and guacamole,

as the case may be with the latter two). This is

how they become “acquired” tastes. Combining

them with other familiar tastes, or with situations

that are in themselves enjoyable, reinforces the

enjoyment factor.

You can train your taste buds to prefer different

flavors, including those you didn’t like as a

younger person, with 5 to 10 repeated exposures.

Plus, with age comes information and education.

That kale-touting, Brussels sprouts-loving holistic

food coach you know could easily have been a

potato chip, Ring Ding junkie 10 years ago, but

through education and an active process of

learning to like more nutritious things, may have

adjusted her preferences. When we start to learn

which foods feel best in our bodies and which are

unhealthy for us, we begin to base our food

decisions on these qualifiers, rather than strictly

on taste. As we shift away from high-sugar, high-

salt foods of our younger years, our tastes will

adapt to what’s most consistent. When the body

isn’t flooded with fructose and artificial

sweeteners, things like carrots and beets can start

to taste extra sweet.

We can encourage the body to prefer these more

natural tastes and their built-in nutritional

benefits by shifting our diet to simpler but still

delicious foods. We can also use repeated

exposure and motivators like good health and a

varied diet to retrain our buds and, ultimately, our

eating habits.

This article originally appeared on ClassPass, a

monthly membership that connects you to more

than 8,000 of the best fitness studios worldwide.

Have you been thinking about trying it? Learn

more here.

" Tweet# Pin $ !

Share% Email 16

SHARES

16

FILED UNDER: STORIES

TAGGED W I TH : taste

« Secrets of a Texas BBQ

Pitmaster

Paleo Monday to Friday:

Banana Soufflé »

Trackbacks

Your Unique Profile: Bio-Individuality –

Lauryn’s Lifestyle says:

April 22, 2019 at 6:57 am

[…] Also, it takes about two weeks for

our taste buds to change, meaning that

after two weeks you might not even be

missing the foods you cut out at all! You

can read more about this cool fact here.

[…]

FREE E-BOOK WHEN YOU

SUBSCRIBE!

First Name

Last Name

Enter email address

GO!

TERMS OF USE

Privacy Policy

Terms and Conditions

FOLLOW EDIBLE

COMMUNITIES

HOW TO REACH US

About Us

Contact us

Advertise with us

Subscribe to Edible Magazines

Start your own Edible

Write for Us

COPYRIGHT © 2019 EDIBLE COMMUNITIES

You might also like

- Conditional WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesConditional WPS OfficeTHOYYIBAH VIICNo ratings yet

- PDF PDFDocument6 pagesPDF PDFBamwinataNo ratings yet

- Savor the Flavor: A Mouthwatering Journey to Mindful Eating BlissFrom EverandSavor the Flavor: A Mouthwatering Journey to Mindful Eating BlissNo ratings yet

- Bksum TheendofovereatingDocument11 pagesBksum Theendofovereatingapi-240679680No ratings yet

- The Role of TastesDocument1 pageThe Role of TastesRičardasNo ratings yet

- Food Cravings: Simple Strategies to Help Deal with Craving for Sugar & Junk Food: Eating DisordersFrom EverandFood Cravings: Simple Strategies to Help Deal with Craving for Sugar & Junk Food: Eating DisordersRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Tell Me What You Eat and I Will Tell You Who You Are.From EverandTell Me What You Eat and I Will Tell You Who You Are.No ratings yet

- Healthy Eating: The Beginner's Guide On How To Eat Healthy and Stick To ItDocument23 pagesHealthy Eating: The Beginner's Guide On How To Eat Healthy and Stick To ItRabya AmjadNo ratings yet

- Overcome Emotional Eating and Stop Cravings: Understand the Causes of Binge Eating and Food Cravings, Successfully Combat Eating Disorders and Find Your Way to Your Desired Weight and Better HealthFrom EverandOvercome Emotional Eating and Stop Cravings: Understand the Causes of Binge Eating and Food Cravings, Successfully Combat Eating Disorders and Find Your Way to Your Desired Weight and Better HealthNo ratings yet

- Người siêu vị giác và vị giác yếu: Bình thường có tốt hơn không- wed HarvardDocument15 pagesNgười siêu vị giác và vị giác yếu: Bình thường có tốt hơn không- wed HarvardNam NguyenHoangNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document43 pagesLecture 4MUHAMMAD LUQMAN HAKIMI MOHD ZAMRINo ratings yet

- Partners in Flavour: TasteDocument2 pagesPartners in Flavour: Tastein_angel03No ratings yet

- Secrets of My Vegan Kitchen: A Journey into Reversing My Diabetes Without MedicationFrom EverandSecrets of My Vegan Kitchen: A Journey into Reversing My Diabetes Without MedicationNo ratings yet

- 6 TastesDocument2 pages6 TastesFrancine PerreaultNo ratings yet

- You Are What You EatDocument8 pagesYou Are What You EatBeata PieńkowskaNo ratings yet

- The Noom Kitchen: 100 Healthy, Delicious, Flexible Recipes for Every DayFrom EverandThe Noom Kitchen: 100 Healthy, Delicious, Flexible Recipes for Every DayNo ratings yet

- The Everything Guide to Gut Health: Boost Your Immune System, Eliminate Disease, and Restore Digestive HealthFrom EverandThe Everything Guide to Gut Health: Boost Your Immune System, Eliminate Disease, and Restore Digestive HealthNo ratings yet

- Raw Awakening: Your Ultimate Guide to the Raw Food DietFrom EverandRaw Awakening: Your Ultimate Guide to the Raw Food DietRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Intuitive Eating: Build a Healthy Relationship with Food. Prevent Binge Eating in a Mindful Eating Way with a Revolutionary Program. Workbook Included to Achieve Visible Results in A Short TimeFrom EverandIntuitive Eating: Build a Healthy Relationship with Food. Prevent Binge Eating in a Mindful Eating Way with a Revolutionary Program. Workbook Included to Achieve Visible Results in A Short TimeNo ratings yet

- Natural Cures for Constipation: Curing Constipation PermanentlyFrom EverandNatural Cures for Constipation: Curing Constipation PermanentlyNo ratings yet

- How to End A Binge Eating Disorder: A Treatment Guide to Anxiety, Healing, & Diet Without MedicationFrom EverandHow to End A Binge Eating Disorder: A Treatment Guide to Anxiety, Healing, & Diet Without MedicationNo ratings yet

- How To Prepare Comfort Food Your Family Will Love: 75 Delectable Comfort Food RecipesFrom EverandHow To Prepare Comfort Food Your Family Will Love: 75 Delectable Comfort Food RecipesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Mindful Eating: Develop a Better Relationship with Food through Mindfulness, Overcome Eating Disorders (Overeating, Food Addiction, Emotional and Binge Eating), Enjoy Healthy Weight Loss without DietsFrom EverandMindful Eating: Develop a Better Relationship with Food through Mindfulness, Overcome Eating Disorders (Overeating, Food Addiction, Emotional and Binge Eating), Enjoy Healthy Weight Loss without DietsNo ratings yet

- Emotional Eating; How to Understand, Control and Stop Emotional Eating or Binge Eating. A Beginner's Guide to Emotional EatingFrom EverandEmotional Eating; How to Understand, Control and Stop Emotional Eating or Binge Eating. A Beginner's Guide to Emotional EatingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Food That Grows: A Practical Guide To Healthy Living With Whole Food RecipeFrom EverandFood That Grows: A Practical Guide To Healthy Living With Whole Food RecipeNo ratings yet

- More Than A Matter of TasteDocument7 pagesMore Than A Matter of TasteCostin RaducanuNo ratings yet

- Superfood Juices, Smoothies & Drinks: Advice and Recipes to Lose Weight, Prevent Illness, and Improve Your Emotional and Physical HealthFrom EverandSuperfood Juices, Smoothies & Drinks: Advice and Recipes to Lose Weight, Prevent Illness, and Improve Your Emotional and Physical HealthNo ratings yet

- The Alkaline Diet Made Easy: A Beginner's Guide to Dr. Sebi's Approved Herbs and Eating a Plant-Based Diet to Lose Weight, Fight Inflammation, Repair the Immune System and Fight Chronic DiseasesFrom EverandThe Alkaline Diet Made Easy: A Beginner's Guide to Dr. Sebi's Approved Herbs and Eating a Plant-Based Diet to Lose Weight, Fight Inflammation, Repair the Immune System and Fight Chronic DiseasesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)

- CEU Nutrition in TCMDocument17 pagesCEU Nutrition in TCMtaoacu2000No ratings yet

- Intuitive Eating GuideDocument5 pagesIntuitive Eating GuideRachel Breeze100% (1)

- Raw Food Diet For Beginners - How To Lose Weight, Feel Great, and Improve Your HealthFrom EverandRaw Food Diet For Beginners - How To Lose Weight, Feel Great, and Improve Your HealthNo ratings yet

- Raw Food Diet: The Beginner's Guide To Raw FoodsFrom EverandRaw Food Diet: The Beginner's Guide To Raw FoodsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- Delightfully Healthy: Change Your Habits, Change Your LifeFrom EverandDelightfully Healthy: Change Your Habits, Change Your LifeNo ratings yet

- Hunger VS AppetiteDocument2 pagesHunger VS AppetiteKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- Crack the Code on Cravings: What Your Cravings Really MeanFrom EverandCrack the Code on Cravings: What Your Cravings Really MeanNo ratings yet

- The Feel Well Project: Experiments in Learning How to Eat, Live and ThinkFrom EverandThe Feel Well Project: Experiments in Learning How to Eat, Live and ThinkNo ratings yet

- Tongue & TasteDocument16 pagesTongue & TasteViniBetsyGeorgeNo ratings yet

- Comp Health 411 MGMT CHPT 2Document39 pagesComp Health 411 MGMT CHPT 2Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Project Chart With FormulasDocument18 pagesProject Chart With FormulasLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- $$$$$ - Daily Pay - $$$$$ - Daily Pay...Document7 pages$$$$$ - Daily Pay - $$$$$ - Daily Pay...Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 5 Year Financial Plan ManufacturingDocument30 pages5 Year Financial Plan ManufacturingLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Binder 3Document7 pagesBinder 3Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- BU3110 - 66 - One Course Model - SyllabusDocument13 pagesBU3110 - 66 - One Course Model - SyllabusLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Debate Opening StatementDocument1 pageDebate Opening StatementLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- HIM Tech MGMT Book Review TermsDocument237 pagesHIM Tech MGMT Book Review TermsLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Allocation of Refund (Including Savings Bond Purchases)Document4 pagesAllocation of Refund (Including Savings Bond Purchases)Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 3print - Elementary StatisticsDocument4 pages3print - Elementary StatisticsLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- AB71LD-LW OnlineSeminar LicenseDocument22 pagesAB71LD-LW OnlineSeminar LicenseLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- CDCR 1515 Fillable Form - 1Document1 pageCDCR 1515 Fillable Form - 1Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- ASH 2014 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule SummaryDocument10 pagesASH 2014 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule SummaryLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 2011 Ehr Selection Guidelines For Health CentersDocument38 pages2011 Ehr Selection Guidelines For Health CentersLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Auto Repair Invoice 28Document2 pagesAuto Repair Invoice 28Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Auto Repair Invoice 12Document1 pageAuto Repair Invoice 12Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Auto Repair Invoice TemplateDocument31 pagesAuto Repair Invoice TemplateLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Closed School Loan Discharge FormDocument5 pagesClosed School Loan Discharge FormLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Dad's Blue ObitDocument3 pagesDad's Blue ObitLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Auto Repair ReceiptDocument1 pageAuto Repair ReceiptLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- New Business DeclarationDocument1 pageNew Business DeclarationLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Check Printing Specifications BusinessDocument2 pagesCheck Printing Specifications BusinessLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

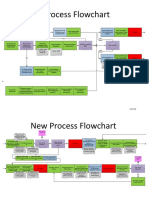

- New Process Flowchart CPOEDocument4 pagesNew Process Flowchart CPOELiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Check Stub Template-1-2Document118 pagesCheck Stub Template-1-2Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Ht204 Statistics Presentation1Document1 pageHt204 Statistics Presentation1Liza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Standard California Residential Lease Agreement TemplateDocument18 pagesStandard California Residential Lease Agreement TemplateLiza GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Surge Impedance LoadingDocument2 pagesSurge Impedance LoadingAnbu AyyappanNo ratings yet

- 2-Design of Slab Non-Traditional FORMWORK.Document55 pages2-Design of Slab Non-Traditional FORMWORK.Eslam SamirNo ratings yet

- Guide Isolators 2017Document180 pagesGuide Isolators 2017GhiloufiNo ratings yet

- 005 - Romulan Warbird (D'Deridex)Document20 pages005 - Romulan Warbird (D'Deridex)Fabien Weissgerber100% (1)

- European Standard EN 1838 Norme Europeenne Europaische NormDocument12 pagesEuropean Standard EN 1838 Norme Europeenne Europaische NormAts ByNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Linear MotionDocument12 pagesChapter 2 Linear MotionFatin AmirNo ratings yet

- Course Task - Week 7Document34 pagesCourse Task - Week 7JoelynMacalintalNo ratings yet

- Genicular Nerves BlockDocument14 pagesGenicular Nerves BlocknsatriotomoNo ratings yet

- BFW 10Document3 pagesBFW 10Manohar PNo ratings yet

- Test B2: Example: O A Because of B As For C Since D As A ResultDocument5 pagesTest B2: Example: O A Because of B As For C Since D As A ResultAgrigoroaiei IonelNo ratings yet

- JY Gembox 2Document5 pagesJY Gembox 2Krepus BlackNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument12 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelTerTalks ChikweyaNo ratings yet

- Radioactive Mind MapDocument16 pagesRadioactive Mind Mapwahidms840% (1)

- Test 5-11-2019 Excretory System - Pharmacist Zaheer AbbasDocument3 pagesTest 5-11-2019 Excretory System - Pharmacist Zaheer AbbasabbaszaheerNo ratings yet

- The Basic Parts of An Airplane and Their FunctionsDocument4 pagesThe Basic Parts of An Airplane and Their FunctionsSubash DhakalNo ratings yet

- Egipto Underweight Case Study MNT1Document14 pagesEgipto Underweight Case Study MNT1Hyacinth M. NotarteNo ratings yet

- Aft MPM Cafs 01Document2 pagesAft MPM Cafs 01Forum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Rohm Bu2090Document12 pagesRohm Bu2090Alberto Carrillo GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Gandolfi - L'Eclissi e L'orbe Magno Del LeoneDocument24 pagesGandolfi - L'Eclissi e L'orbe Magno Del LeoneberixNo ratings yet

- Angkur BetonDocument36 pagesAngkur BetonmhadihsNo ratings yet

- 1741 - Long Span Structures ReportDocument5 pages1741 - Long Span Structures ReportHuzefa SayyedNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 8: Language HandbookDocument2 pagesWorksheet 8: Language HandbookMrs BeyNo ratings yet

- Paul Buckmaster WorksDocument31 pagesPaul Buckmaster WorksGeorge LucasNo ratings yet

- Unit Homework Momentum Its Conservation Ans KeyDocument6 pagesUnit Homework Momentum Its Conservation Ans KeyKristyne Olicia100% (1)

- ASTM A-967-13 Pasivado Inoxidable PDFDocument7 pagesASTM A-967-13 Pasivado Inoxidable PDFmagierezNo ratings yet

- Isolated Roller Guide Shoes WRG200, WRG300Document15 pagesIsolated Roller Guide Shoes WRG200, WRG300Johan GuíaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Energy & Society: Importance of Energy in Our Daily LifeDocument12 pagesIntroduction To Energy & Society: Importance of Energy in Our Daily LifeArun SaiNo ratings yet

- Moc3052 PDFDocument9 pagesMoc3052 PDFHernan JavierNo ratings yet

- BuffersDocument3 pagesBuffersIshak Ika Kovac100% (1)

- Sensory Aspects of Retailing: Theoretical and Practical ImplicationsDocument5 pagesSensory Aspects of Retailing: Theoretical and Practical ImplicationsΑγγελικήΝιρούNo ratings yet