Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PNB V Gancayco

Uploaded by

Joyce KevienOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PNB V Gancayco

Uploaded by

Joyce KevienCopyright:

Available Formats

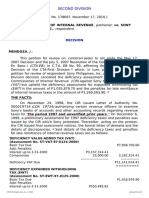

EN BANC

[G.R. No. L-18343. September 30, 1965.]

PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, and EDUARDO Z. ROMUALDEZ,

in his capacity as President of the Philippine National Bank,

plaintiffs-appellants, vs. EMILIO A. GANCAYCO, and

FLORENTINO FLOR, Special Prosecutors of the Dept. of

Justice, defendants-appellees.

Ramon B. de los Reyes and Zoilo P. Perlas for plaintiff-appellants.

Villamor & Gancayco for defendants-appellees.

SYLLABUS

1. BANK DEPOSITS; DISCLOSURE OF BANK ACCOUNTS OF A

DEPOSITOR WHO IS UNDER INVESTIGATION FOR UNEXPLAINED WEALTH. —

Whereas Section 2 of Republic Act No. 1405 provides that bank deposits are

"absolutely confidential ** and, therefore, may not be examined, inquired or

looked into," except in those cases enumerated therein, Section 8 of

Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft Law) directs in mandatory terms that bank

deposits "shall be taken into consideration in the enforcement of this

section, notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary." The only

conclusion possible is that Section 8 of the Anti-Graft Law is intended to

amend Section 2 of Republic Act No. 1405 by providing an additional

exception to the rule against the disclosure of bank deposits.

2. ID.; ID.; DISCLOSURE NOT CONTRARY TO THE POLICY MAKING

BANK DEPOSITS CONFIDENTIAL. — The disclosure would not be contrary to

the policy making bank deposits confidential for while Section 2 of Republic

Act No. 1405 declares bank deposits to be "absolutely confidential" it

nevertheless allows such disclosure in the following instances: (1) upon

written permission of the depositor; (2) in cases of impeachment; (3) upon

order of a competent court in cases of bribery or dereliction of duty of public

officials; (4) in cases where the money deposited is the subject matter of the

litigation. Cases of unexplained wealth are similar to cases of bribery or

dereliction of duty and no reason is seen why these two classes of cases

cannot be excepted from the rule making bank deposits confidential.

DECISION

REGALA, J : p

The principal question presented in this case is whether a bank can be

compelled to disclose the records of accounts of a depositor who is under

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

investigation for unexplained wealth.

This question arose when defendants Emilio A. Gancayco and

Florentino Flor, as special prosecutors of the Department of Justice, required

the plaintiff Philippine National Bank to produce at a hearing to be held at 10

am. on February 20, 1961 the records of the bank deposits of Ernesto T.

Jimenez, former administrator of the Agricultural Credit and Cooperative

Administration, who was then under investigation for unexplained wealth. In

declining to reveal its records, the plaintiff bank invoked republic Act No.

1405 which provides:

SEC. 2. All deposits of whatever nature with banks or banking

institutions in the Philippines including investments in bonds issued by

the Government of the Philippines, its political subdivisions and its

instrumentalities, are hereby considered as of an absolutely

confidential nature and may not be examined, inquired or looked into

by any person, government official, bureau or office, except upon

written permission of the depositor, or in cases of impeachment, or

upon order of a competent court in cases of bribery or dereliction of

duty of public officials, or in cases where the money deposited or

invested is the subject matter of the litigation.

The plaintiff bank also called attention to the penal provision of the law

which reads:

SEC. 5. Any violation of this law will subject the offender upon

conviction, to an imprisonment of not more than five years or a fine of

not more than twenty thousand pesos or both, in the discretion of the

court.

On the other hand, the defendants cited the Anti-Graft and Corrupt

Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019) in support of their claim of authority

and demanded anew that plaintiff Eduardo Z. Romualdez, as bank president,

produce the records or he would be prosecuted for contempt. The law

invoked by the defendant states:

Sec. 8. Dismissal due to unexplained wealth. — If in

accordance with the provisions of Republic Act Numbered One

thousand three hundred seventy-nine, a public official has been found

to have acquired during his incumbency, whether in his name or in the

name of other persons, an amount of property and/or money

manifestly, out of proportion to his salary and to his other lawful

income, that fact shall be a ground for dismissal or removal. Properties

in the name of the spouse and unmarried children of such public

official, may be taken into consideration, when their acquisition

through legitimate means cannot be satisfactorily shown. Bank

deposits shall be taken into consideration in the enforcement of this

section, notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary.

Because of the threat of prosecution, plaintiffs filed an action for

declaratory judgment in the Manila Court of First Instance. After trial, during

which Senator Arturo M. Tolentino, author of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt

Practices Act testified, the court rendered judgment sustaining the power of

the defendants to compel the disclosure of bank accounts of ACCFA

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

Administrator Jimenez. The court said that, by enacting section 8 of the Anti-

Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Congress clearly intended to provide an

additional ground for the examination of bank deposits. Without such

provision, the court added, prosecutors would be hampered if not altogether

frustrated in the prosecution of those charged with having acquired

unexplained wealth while in public office.

From that judgment, plaintiffs appealed to this Court. In brief, plaintiffs'

position is that section 8 of the Anti-Graft Law "simply means that such bank

deposits may be included or added to the assets of the Government official

or employee for the purpose of computing his unexplained wealth if and

when the same are discovered or revealed in the manner authorized by

Section 2 of Republic Act 1405, which are (1) Upon written permission of the

depositor; (2) in cases of impeachment; (3) Upon order of a competent court

in cases of bribery or dereliction of duty of public officials; and (4) In cases

where the money deposited or invested is the subject matter of the

litigation."

In support of their position, plaintiffs contend, first, that the Anti-Graft

Law (which took effect on August 17, 1960) is a general law which cannot be

deemed to have impliedly repealed section 2 of Republic Act No. 1405

(which took effect on Sept. 9, 1955.), because of the rule that repeals by

implication are not favored. Second, they argue that to construe section 8 of

the Anti-Graft Law as allowing inquiry into bank deposits would be to negate

the policy expressed in section 1 of Republic Act No. 1405, which is "to give

encouragement to the people to deposit their money in banking institutions

and to discourage private hoarding so that the same may be utilized by

banks in authorized loans to assist in the economic development of the

country."

Contrary to their claim that their position effects a reconciliation of the

provisions of the two laws, plaintiffs are actually making the provisions of

Republic Act No. 1405 prevail over those of the Anti-Graft Law, because even

without the latter law the balance standing to the depositor's credit can be

considered provided its disclosure is made in any of the cases provided in

Republic Act No. 1405.

The truth is that these laws are so repugnant to each other that no

reconciliation is possible. Thus, while Republic Act No. 1405 provides that

bank deposits are "absolutely confidential . . . and [therefore] may not be

examined, inquired or looked into," except in those cases enumerated

therein, the Anti-Graft Law directs in mandatory terms that bank deposits

"shall be taken into consideration in the enforcement of this section,

notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary." The only conclusion

possible is that section 8 of the Anti-Graft Law is intended to amend section

2 of Republic Act No. 1405 by providing an additional exception to the rule

against the disclosure of bank deposits.

Indeed, it is said that if the new law is inconsistent with or repugnant to

the old law, the presumption against the intent to repeal by implication is

overthrown because the inconsistency or repugnancy reveals an intent to

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

repeal the existing law. And whether a statute, either in its entirety or in

part, has been repealed by implication is ultimately a matter of legislative

intent. (Crawford, The Construction of Statutes pp. 309-310. Cf. Iloilo Palay

and Corn Planters Ass'n. v. Feliciano, G.R. No. L-24022, March 3, 1965).

The recent case of People v. De Venecia, G. R. No. L-20808, July 31,

1965 invites comparison with this case. There it was held:

"The result is that although Sec. 54 [Rev. Election Code]

prohibits a classified civil service employee from aiding any

candidate, Sec 29 [Civil Service Act of 1959] allows such classified

employee to express his views on current political problems or

issues, or to mention the name of his candidate for public office,

even if such expression of views or mention of names may result

in aiding one particular candidate. In other words, the last

paragraph of Sec. 29 is an exception to Sec. 54; at most, an

amendment to Sec. 54."

With regard to the claim that disclosure would be contrary to the policy

making bank deposits confidential, it is enough to point out that while

section 2 of Republic Act No. 1405 declares bank deposits to be "absolutely

confidential" it nevertheless allows such disclosure in the following

instances: (1) Upon written permission of the depositor; (2) In cases of

impeachment; (2) Upon order of a competent court in cases of bribery or

dereliction of duty of public officials; (4) In cases where the money deposited

is the subject of the litigation. Cases of unexplained wealth are similar to

cases of bribery or dereliction of duty and no reason is seen why these two

classes of cases cannot be excepted from the rule making bank deposits

confidential. The policy as to one cannot be different from the policy as to

the other. This policy expresses the notion that a public office is a public

trust and any person who enters upon its discharge does so with the full

knowledge that his life, so far as relevant to his duty, is open to public

scrutiny.

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is affirmed, without

pronouncement as to costs.

Concepcion, Reyes, J. B. L., Makalintal, Bengzon, J.P., and Zaldivar, JJ.,

concur.

Bengzon, C.J. and Bautista Angelo, J., are on an official trip to Tokyo.

Barrera, J., is on leave.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Francisco v. House of Representatives (Case Summary)Document6 pagesFrancisco v. House of Representatives (Case Summary)Jerome Bernabe83% (6)

- KASAMA ConstitutionDocument19 pagesKASAMA ConstitutionCharles D. FloresNo ratings yet

- SSG Registration Form For Clubs and OrganizationsDocument11 pagesSSG Registration Form For Clubs and OrganizationsEugene Salem AbulocNo ratings yet

- Commissioner V Sony PDFDocument11 pagesCommissioner V Sony PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Castillo V UniwideDocument7 pagesCastillo V UniwideJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Lopez V City of ManilaDocument16 pagesLopez V City of ManilaJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Asa V PeopleDocument7 pagesAsa V PeopleJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V CahiligDocument7 pagesPeople V CahiligJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Respondent Ozaeta, Roxas, Lichauco & Picazo Solicitor General Juan R. Liwag Solicitor Jose P. AlejandroDocument7 pagesPetitioners Respondent Ozaeta, Roxas, Lichauco & Picazo Solicitor General Juan R. Liwag Solicitor Jose P. AlejandroJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Medicard V CIR PDFDocument19 pagesMedicard V CIR PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V CallaoDocument16 pagesPeople V CallaoJoyce Kevien100% (1)

- Petitioner Respondents: Third DivisionDocument15 pagesPetitioner Respondents: Third DivisionJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V Dela CruzDocument7 pagesPeople V Dela CruzJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V AlmazanDocument9 pagesPeople V AlmazanJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Buebos V PeopelDocument15 pagesBuebos V PeopelJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Pante V PeopleDocument16 pagesPante V PeopleJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Napolis V PeopleDocument11 pagesNapolis V PeopleJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Osorio V NaveraDocument14 pagesOsorio V NaveraJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V AbarcaDocument7 pagesPeople V AbarcaJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Cayao V Del MundoDocument7 pagesCayao V Del MundoJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Intod V CADocument8 pagesIntod V CAJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V Villamar PDFDocument8 pagesPeople V Villamar PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- People V SantianoDocument12 pagesPeople V SantianoJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- British American V CamachoDocument46 pagesBritish American V CamachoJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Timoner V People PDFDocument4 pagesTimoner V People PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Republic V BolanteDocument24 pagesRepublic V BolanteJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Garma V People PDFDocument12 pagesGarma V People PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- CIR V Filinvest PDFDocument24 pagesCIR V Filinvest PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Tiu V CADocument12 pagesTiu V CAJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Barbasa V Tuquero PDFDocument7 pagesBarbasa V Tuquero PDFJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Gullas V PNBDocument4 pagesGullas V PNBJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- Gonzales III V Office of The President Case DigestDocument3 pagesGonzales III V Office of The President Case DigestKarmaranthNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Retail Management A Strategic Approach 12th Edition BermanDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Retail Management A Strategic Approach 12th Edition Bermancreutzerpilement1x24a100% (37)

- Dimaporo vs. Mitra Jr.Document3 pagesDimaporo vs. Mitra Jr.Rochedale ColasiNo ratings yet

- Constitution SummaryDocument9 pagesConstitution SummaryVirgilio TomasNo ratings yet

- Re-Accreditation Requirements 2015Document86 pagesRe-Accreditation Requirements 2015CarlosNgNo ratings yet

- 1949 Nacionalista - Party - v. - Bautista20210424 12 SgiirkDocument17 pages1949 Nacionalista - Party - v. - Bautista20210424 12 SgiirkKiz AndersonNo ratings yet

- Article Vii, Section 1 Cases-Case DigestDocument7 pagesArticle Vii, Section 1 Cases-Case DigestCamelle Gacusana MansanadeNo ratings yet

- Impeachment LetterDocument1 pageImpeachment LetterJohn ArchibaldNo ratings yet

- SH0815Document16 pagesSH0815Anonymous 9eadjPSJNgNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Constitution 2008 English VersionDocument213 pagesMyanmar Constitution 2008 English VersionMyanmar Man83% (6)

- Full Download Health The Basics The Mastering Health Edition 12th Edition Donatelle Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Health The Basics The Mastering Health Edition 12th Edition Donatelle Solutions Manualretainalgrainascjy100% (37)

- 02-04-08 BuzzFlash-Elizabeth Holtzman's Courageous Call ForDocument7 pages02-04-08 BuzzFlash-Elizabeth Holtzman's Courageous Call ForMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- Statcon C3 Cases PDFDocument190 pagesStatcon C3 Cases PDFCien Ego-OganNo ratings yet

- Public OfficersDocument37 pagesPublic OfficersPilacan KarylNo ratings yet

- Judicial Accountability in IndiaDocument12 pagesJudicial Accountability in IndiaAnoop BardiyaNo ratings yet

- Stat Con DigestsDocument30 pagesStat Con DigestsEffy SantosNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws of SSCDocument12 pagesConstitution and By-Laws of SSCJaypee Mercado Roaquin100% (1)

- Republic Vs Sereno GR No. 237428 May 11, 2018Document17 pagesRepublic Vs Sereno GR No. 237428 May 11, 2018Jacquelyn RamosNo ratings yet

- Pale CaseDocument11 pagesPale Casewilliam091090No ratings yet

- C RavichandranDocument18 pagesC RavichandranJahnavi PandeyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Maternity Pediatric Nursing Leifer 5th Edition Test BankDocument36 pagesIntroduction To Maternity Pediatric Nursing Leifer 5th Edition Test Banklaxator.rabotru5i37100% (37)

- SSG of BHFHS Constitution and By-LawsDocument9 pagesSSG of BHFHS Constitution and By-LawsNash Anthony SarecepNo ratings yet

- LAMP v. Secretary of Budget and ManagementDocument2 pagesLAMP v. Secretary of Budget and ManagementRiva Mae CometaNo ratings yet

- The 1996 Student Council ConsttitutionDocument26 pagesThe 1996 Student Council ConsttitutionJoseph Bernard Areño MarzanNo ratings yet

- Sandiganbayan and OmbudsmanDocument24 pagesSandiganbayan and OmbudsmanCarla January OngNo ratings yet

- Final Complaint vs. OmbudsmanDocument32 pagesFinal Complaint vs. OmbudsmanManuel L. Quezon III50% (2)

- Union and State Executive Part IDocument57 pagesUnion and State Executive Part ISHIREEN MOTINo ratings yet