Professional Documents

Culture Documents

E Balle 2010

E Balle 2010

Uploaded by

ppapapCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Prevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchMuhammad RaflirNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic Pterygium Surgery Techniques and Long-Term OutcomesDocument7 pagesCosmetic Pterygium Surgery Techniques and Long-Term OutcomesrhizkyNo ratings yet

- Referral Process in Patients With Uveitis: A Challenge in The Health SystemDocument10 pagesReferral Process in Patients With Uveitis: A Challenge in The Health Systemfedcaf18No ratings yet

- OPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216Document5 pagesOPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216ppapapNo ratings yet

- Five-Year Results of ViscotrabeculotomyDocument10 pagesFive-Year Results of ViscotrabeculotomyChintya Redina HapsariNo ratings yet

- OPTH 143898 Posterior Vitreous Detachment Prevalence of and Risk Facto 091817Document7 pagesOPTH 143898 Posterior Vitreous Detachment Prevalence of and Risk Facto 091817Pangala NitaNo ratings yet

- Resiko Jatuh GlaukomaDocument5 pagesResiko Jatuh GlaukomayohanaNo ratings yet

- Kobia Acquah Et Al 2022 Prevalence of Keratoconus in Ghana A Hospital Based Study of Tertiary Eye Care FacilitiesDocument10 pagesKobia Acquah Et Al 2022 Prevalence of Keratoconus in Ghana A Hospital Based Study of Tertiary Eye Care FacilitiesEugene KusiNo ratings yet

- China Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesChina Risk FactorsNoor MohammadNo ratings yet

- Resolution of Pinguecula-Related Dry Eye Disease ADocument4 pagesResolution of Pinguecula-Related Dry Eye Disease ASylvia MtrianiNo ratings yet

- Red Eye: A Guide For Non-Specialists: MedicineDocument14 pagesRed Eye: A Guide For Non-Specialists: MedicineFapuw Parawansa100% (1)

- COMPLETODocument9 pagesCOMPLETOZarella Ramírez BorreroNo ratings yet

- Accommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationDocument7 pagesAccommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationpoppyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Mata KeratitisDocument5 pagesJurnal Mata KeratitisDayuNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadDocument5 pagesCongenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadSherry CkyNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors in Underserved Rural AreasDocument7 pagesThe Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors in Underserved Rural AreasradifNo ratings yet

- Abrar - Anterior Chamber Angle in Aniridia With and Whout GloucomaDocument5 pagesAbrar - Anterior Chamber Angle in Aniridia With and Whout Gloucomabudi haryadiNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesPattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDr. Abhishek OnkarNo ratings yet

- Schiefer 2016Document16 pagesSchiefer 2016Eric PavónNo ratings yet

- Asthenopía in ChildrenDocument9 pagesAsthenopía in ChildrenMigUel SánchezNo ratings yet

- Ocular Manifestations of Leprosy - A Clinical Study: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesOcular Manifestations of Leprosy - A Clinical Study: Original ArticleAzizah TjakradidjajaNo ratings yet

- Sakamoto 2018Document6 pagesSakamoto 2018Widya WibelNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Andi CitraDocument10 pagesJurnal Andi Citrayusti aisyahNo ratings yet

- Clinical Profile and Demographics of Glaucoma Patients Managed in A Philippine Tertiary HospitalDocument7 pagesClinical Profile and Demographics of Glaucoma Patients Managed in A Philippine Tertiary HospitalPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- JWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217Document6 pagesJWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217ppapapNo ratings yet

- Dry Eyes and Digital Devices 1Document11 pagesDry Eyes and Digital Devices 1Koas HAYUU 2022No ratings yet

- Ukponmwan 2004Document4 pagesUkponmwan 2004ppapapNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Retinitis Pigmentosa: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument8 pagesUnilateral Retinitis Pigmentosa: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureWidyawati SasmitaNo ratings yet

- 971 FullDocument3 pages971 Fullوسام الرعويNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors Among Adults Attending at A Tertiary Care Hospital - A Retrospective StudyDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors Among Adults Attending at A Tertiary Care Hospital - A Retrospective StudyyuyuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Asli Word - Intan MalafinaDocument11 pagesJurnal Asli Word - Intan MalafinaIntanNo ratings yet

- Progression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent CohortDocument6 pagesProgression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent Cohortfarras fairuzzakiahNo ratings yet

- Detection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanDocument8 pagesDetection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanPuskesmas Purwokerto SelatanNo ratings yet

- Prospective Evaluation of Visual Function For Early Detection of Ethambutol ToxicityDocument5 pagesProspective Evaluation of Visual Function For Early Detection of Ethambutol Toxicitysatyagraha84No ratings yet

- Corneal Laceration Caused by River Crab: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveDocument4 pagesCorneal Laceration Caused by River Crab: Clinical Ophthalmology Dovesiti rumaisaNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument9 pagesGlaucomaREGINE YEO ZHI SHUENNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainIndah Nur LathifahNo ratings yet

- Causes and Correction Dissatisfaction After ImpDocument6 pagesCauses and Correction Dissatisfaction After ImpSATYAJITSINH GOHILNo ratings yet

- Sympathetic Ophthalmia After Vitreoretinal Surgery: A Report of Two CasesDocument11 pagesSympathetic Ophthalmia After Vitreoretinal Surgery: A Report of Two CasesAlexander RezaNo ratings yet

- 227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Document5 pages227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Ayele BizunehNo ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2020 041854Document8 pagesBmjopen 2020 041854MufassiraturrahmahNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study of The Association Between Fuchs and Glaucoma - CopieDocument5 pagesA Retrospective Study of The Association Between Fuchs and Glaucoma - CopiefellaarfiNo ratings yet

- Video Interpretation and Diagnosis of Pediatric Amblyopia and Eye DiseasseDocument7 pagesVideo Interpretation and Diagnosis of Pediatric Amblyopia and Eye DiseasseDinda Ajeng AninditaNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Ophthalmology Case ReportsDocument6 pagesAmerican Journal of Ophthalmology Case ReportsPuput Anistya HarianiNo ratings yet

- Eye 2008158Document10 pagesEye 2008158KillNoiseNo ratings yet

- Optimal Management of Pediatric Keratoconus: Challenges and SolutionsDocument9 pagesOptimal Management of Pediatric Keratoconus: Challenges and SolutionsJesus Rodriguez NoriegaNo ratings yet

- Exopthal 8Document7 pagesExopthal 8Perdana SihiteNo ratings yet

- Uveitic Glaucoma Management With Recurrent Uveitis EpisodeDocument6 pagesUveitic Glaucoma Management With Recurrent Uveitis EpisodeLina Shabrina QoribNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Uveitis in The Mid-Atlantic United States: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveDocument6 pagesTraumatic Uveitis in The Mid-Atlantic United States: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveRanhie Pen'ned CendhirhieNo ratings yet

- Intermittent Exotropia Our Experience in Surgical Outcomes 2155 9570 1000722Document3 pagesIntermittent Exotropia Our Experience in Surgical Outcomes 2155 9570 1000722Ikmal ShahromNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Ultrasonography and Histologic ExaminationDocument13 pagesComparison of Ultrasonography and Histologic ExaminationLeonardo A. Muñoz DominguezNo ratings yet

- OPTH 118409 Undesirable Systemic Side Effects of Ophthalmic Drops From T 120716Document9 pagesOPTH 118409 Undesirable Systemic Side Effects of Ophthalmic Drops From T 120716Optm Abdul AzizNo ratings yet

- A Rare Complication of Combined Oral Contraceptives (Cocs) : Optic NeuritisDocument3 pagesA Rare Complication of Combined Oral Contraceptives (Cocs) : Optic NeuritisGufront MustofaNo ratings yet

- Visual Outcomes Following Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) in Wangaya HospitalDocument4 pagesVisual Outcomes Following Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) in Wangaya HospitalKrisnhalianiNo ratings yet

- Safety of Cetirizine Ophthalmic Solution 0.24% For The Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis in Adult and Pediatric SubjectsDocument11 pagesSafety of Cetirizine Ophthalmic Solution 0.24% For The Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis in Adult and Pediatric SubjectsrismaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Tear Film EvaluationDocument5 pagesThesis Tear Film EvaluationKjhnNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyDocument4 pagesClinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyFi NoNo ratings yet

- Prevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDocument10 pagesPrevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDaniel AsmareNo ratings yet

- Bjophthalmol 2020 317832Document5 pagesBjophthalmol 2020 317832kenly chandraNo ratings yet

- OPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216Document5 pagesOPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216ppapapNo ratings yet

- JWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217Document6 pagesJWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217ppapapNo ratings yet

- Hartong 2006Document15 pagesHartong 2006ppapapNo ratings yet

- Ukponmwan 2004Document4 pagesUkponmwan 2004ppapapNo ratings yet

- David Abel: As Pandemic Wears On, Despair at Epicenter of Addiction Crisis Deepens byDocument4 pagesDavid Abel: As Pandemic Wears On, Despair at Epicenter of Addiction Crisis Deepens byCourtney CrowleyNo ratings yet

- Shillings Dialectical LensDocument3 pagesShillings Dialectical Lensapi-399928223No ratings yet

- NeurotransmissionDocument3 pagesNeurotransmissionElilta MihreteabNo ratings yet

- Scalp Block For Awake Craniotomy Lidocaine-BupivacDocument10 pagesScalp Block For Awake Craniotomy Lidocaine-BupivacremediNo ratings yet

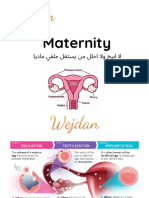

- Maternity, Wejdan NDocument26 pagesMaternity, Wejdan NirrajawahirNo ratings yet

- Activity Date Venue Responsibility Resources OutputDocument3 pagesActivity Date Venue Responsibility Resources OutputLahiru DilshanNo ratings yet

- The Wii Club: Gaming For Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese YouthDocument4 pagesThe Wii Club: Gaming For Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese YouthAXEL FRANK ALMONTE CUBANo ratings yet

- Artikel Rev 1Document19 pagesArtikel Rev 1ChrisnaArdhyaMedikaNo ratings yet

- USP General Chapter : Pharmaceutical Compounding - Sterile PreparationsDocument37 pagesUSP General Chapter : Pharmaceutical Compounding - Sterile PreparationsRRR1No ratings yet

- How To Manage Cortisol Levels With Maca RootDocument19 pagesHow To Manage Cortisol Levels With Maca RootCalvin McDuffieNo ratings yet

- Chapter III Lesson 2 BiodiversityDocument48 pagesChapter III Lesson 2 BiodiversityMichael James CaminoNo ratings yet

- Amazing Science 5 - Unit 4Document1 pageAmazing Science 5 - Unit 4Nguyễn Khương LinhNo ratings yet

- Point of Care Risk Assessment (PCRA) : Assess The Task, The Patient and The Environment Prior To Each Patient InteractionDocument1 pagePoint of Care Risk Assessment (PCRA) : Assess The Task, The Patient and The Environment Prior To Each Patient InteractionchrisNo ratings yet

- اسئلة وزارة الصحة للالتحاق ببرنامج الاقامة والامتيازDocument68 pagesاسئلة وزارة الصحة للالتحاق ببرنامج الاقامة والامتيازAhmad HamdanNo ratings yet

- Notes 1Document5 pagesNotes 1logonautNo ratings yet

- Alternative Carriers in Dry Powder InhalerDocument9 pagesAlternative Carriers in Dry Powder InhalerApoorva KNo ratings yet

- Sindrom Uko Ene Osobe (Moersch-Woltman) : Lije Vjesn 2010 132:110-114Document5 pagesSindrom Uko Ene Osobe (Moersch-Woltman) : Lije Vjesn 2010 132:110-114bimtolaNo ratings yet

- Jumbled Letter Game WoundDocument12 pagesJumbled Letter Game WoundDyan Nuli AngrengganiNo ratings yet

- Basic Coronary Angiography All SlidesDocument55 pagesBasic Coronary Angiography All SlidesSaud ShirwanNo ratings yet

- Angeles University Foundation: College of Nursing Nursing Care PlanDocument2 pagesAngeles University Foundation: College of Nursing Nursing Care PlanJohn CuencoNo ratings yet

- Upper Motor Neuron Vs Lower Motor Neuron AtfDocument4 pagesUpper Motor Neuron Vs Lower Motor Neuron AtfRishi VermaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Animal HealthDocument9 pagesModule 5 Animal HealthArlyn Joy RiñoNo ratings yet

- English8 q1 Mod5 ExpressingEmotionalResponseandReactions v3-2Document37 pagesEnglish8 q1 Mod5 ExpressingEmotionalResponseandReactions v3-2Aljerr Laxamana100% (3)

- Cbse Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper - 1 SAIDocument10 pagesCbse Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper - 1 SAIKaran KumarNo ratings yet

- Caring For Stroke PatientsDocument4 pagesCaring For Stroke PatientsshydeeNo ratings yet

- Clean Water and SanitationDocument5 pagesClean Water and SanitationSarah azizahNo ratings yet

- قرار مجلس الوزراء رقم 28 بشأن نظام نقل الدمDocument44 pagesقرار مجلس الوزراء رقم 28 بشأن نظام نقل الدمAbood dot netNo ratings yet

- Science 10 Q3 Module 3Document26 pagesScience 10 Q3 Module 3090406No ratings yet

- Review Related Studies Related To Teenage Pregnancy (Foreign)Document44 pagesReview Related Studies Related To Teenage Pregnancy (Foreign)ruth ann solitarioNo ratings yet

- Short Cases in MedicineDocument30 pagesShort Cases in MedicineselamuNo ratings yet

E Balle 2010

E Balle 2010

Uploaded by

ppapapOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

E Balle 2010

E Balle 2010

Uploaded by

ppapapCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article O r i g i n al Re s ea r c h

Blindness and visual impairment in retinitis

pigmentosa: a Cameroonian hospital-based study

Clinical Ophthalmology downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 45.148.233.248 on 27-Apr-2020

This article was published in the following Dove Press journal:

Clinical Ophthalmology

23 June 2010

Number of times this article has been viewed

André Omgbwa Eballe 1 Aim: We performed a retrospective, analytical study in February 2010 on all retinitis pigmentosa

Godefroy Koki 2 cases seen during ophthalmologic consultation at the Gyneco-Obstetrics and Pediatric Hospital

Claude Bernard Emche 2 of Yaounde between March 2002 and December 2009 (82 months). The aim of this research

Lucienne Assumpta Bella 2 was to determine the significance of blindness and visual impairment associated with retinitis

For personal use only.

pigmentosa in Cameroon.

Jeanne Mayouego Kouam 2

Results: Forty cases were reported, corresponding to a hospital prevalence of 1.6/1000 (21 men

Justin Melong 3

and 19 women). The average age of the patients was 43.3 ± 18 years, ranging between 6 and

1

Faculty of Medicine and 74 years. Bilateral blindness and low vision was noted in 30% and 27.5% of patients, respec-

Pharmaceutical Sciences, University

of Douala; 2Faculty of Medicine and tively. The average age of patients with low vision was 40.38 ± 16.27 years and the average age

Biomedical Sciences, University of of those with bilateral blindness was 51.08 ± 15.79 years. Retinitis pigmentosa was bilateral in

Yaoundé; 3Translation Unit, Ministry

all cases and isolated (without any eye or general additional disease) in 67.5% of cases.

of Public Health, Yaoundé, Cameroon

Conclusion: Visual impairment is common and becomes even more severe with aging. Patients

should be screened to enable them to benefit from management focusing on both appropriate

treatment and genetic counseling.

Keywords: retinitis pigmentosa, Cameroon, blindness, Yaoundé

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa is a genetic disorder with diffuse retinal dystrophy which, in most

cases, primarily affects the rods initially, with subsequent degeneration of cones. Its

prevalence ranges from 1/3000 to 1/5000.1,2 Transmission of retinitis pigmentosa is

genetic and may be by various modes, ie, autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or

X-linked recessive.3 Retinitis pigmentosa is a leading cause of blindness and incurable

visual impairment, owing to its irreversible evolution towards loss of central vision.

We undertook this work in order to determine for the first time the significance of

blindness and visual impairment associated with retinitis pigmentosa in Cameroon.

Methods

A retrospective study was carried out on all retinitis pigmentosa cases seen in the out-

patients’ clinic at the Ophthalmological Unit of the Gyneco-Obstetrics and Pediatric

Correspondence: André Omgbwa Eballe Hospital of Yaoundé between March 2002 and December 2009 (82 months). The files of

Ophthalmology Unit, patients with retinitis pigmentosa were reviewed. The diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa

Gyneco-Obstetric and Pediatric Hospital

of Yaoundé, PO Box 4362,Yaoundé,

was made on the basis of an examination of the ocular fundus using a biomicroscope,

Cameroon the three ophthalmoscopic criteria being retinal hyperpigmentation in star clusters

Tel +11 237 9965 4468

Fax +11 237 2221 2430

(osteoblasts), arterial narrowing, and waxy pallor of the papilla. Far visual acuity on

Email andyeballe@gmail.com the Snellen scale, intraocular pressure using an air-pulse tonometer, abnormalities in

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2010:4 661–665 661

Dovepress © 2010 Eballe et al, publisher and licensee Dove Medical Press Ltd. This is an Open Access article

11566 which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Eballe et al Dovepress

the anterior segment, and the ocular fundus of each patient was not diagnosed in siblings of affected patients, in cases

were also noted. Performance of additional examinations, where brothers and/or sisters attended an ophthalmologic

ie, automatic visual field and retinal angiography was not consultation requested by the attending physician.

systematic, and few patients, for financial reasons, had visual The analysis of visual acuity revealed binocular blindness

field assessment. Electroretinography (ERG) and genetic tests in 12 patients (30%) and low vision in 11 cases (27.5%, see

were not performed in our study due to the inadequate level Figure 1). One case of monocular blindness was noted in a

of technical expertise at the unit. patient with a unilateral macular hole.

The variables analyzed were age, gender, main complaint, Six of 11 patients (54.54%) with low vision were older

Clinical Ophthalmology downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 45.148.233.248 on 27-Apr-2020

far visual acuity, intraocular pressure, ocular fundus, and than 40 years and nine of 12 cases (75%) of bilateral blind-

visual field. The chi-squared test was used for comparison, ness were recorded in patients older than 40 years (Table 2).

and was considered significant at P , 0.05. The average age of patients with low vision was 40.38 ±

The classification of visual impairment was made using 16.27 years and that of patients with bilateral blindness was

the analysis of visual acuity as defined by the World Health 51.08 ± 15.79 years.

Organization,4 ie, binocular blindness (visual acuity ,1/20 The average intraocular pressure observed was 14.30 ±

of the better eye with correction, and low vision (visual 2.86 mmHg and 14.83 ± 5.24 mmHg in the right eye and left

acuity ,3/10 and $1/20 of the better eye with correction). eye, respectively. The intraocular pressure was above normal

We considered any patient with a corrected visual acuity of (21 mmHg) in three eyes from three different patients.

the better eye .3/10 and that of the impaired eye ,1/20 as Retinitis pigmentosa was bilateral in all our patients,

For personal use only.

having monocular blindness. and isolated (without any other eye or additional disease)

in 27 cases (67.5%). The major associated pathologies were

Results cataract (four cases), chronic open angle glaucoma (three

Of 24,205 files selected for study, 40 cases of retinitis cases), age-related macular degeneration (ARMD, three

pigmentosa were identified, corresponding to a hospital cases), and high myopia (two cases, Table 3). No deafness

prevalence of 1.6/1000. The disease was noted in 21 men and was noticed to prompt consideration of Usher syndrome.

19 women. The average age of patients was 43.3 ± 18.2 years, Table 4 shows that nine of 13 patients (69.23%) with related

with a range of 6–74 years. The most represented age group diseases were older than 40 years.

was 41–50 years, which included 11 patients (27.5%), fol- Visual f ield examination was performed in only

lowed by patients aged .60 years (eight cases, 20%), with 10 patients. All reports on automated perimetry revealed

only four cases (10%) ,20 years. In total, 24 patients (60%) tubular visual fields with absolute annular scotoma.

were .40 years (Table 1).

The main complaint was a drop in visual acuity, which Discussion

was found in 35 patients (87.5%), followed by night blindness This study focused on patients treated in a hospital-based

in 28 patients (70%). It should be noted that a single patient ophthalmologic outpatients unit. The hospital prevalence

could have several reasons for consultation. With regard of retinitis pigmentosa (1.6/1000) would clearly not be

to family history, we noted 10 cases (25%) of a history of representative of the entire Cameroonian population. In

blindness in relatives, but the cause of this blindness was Caucasian countries, the prevalence in general population

unknown to the patient or the family. No case of parental

consanguinity was reported. In addition, retinitis pigmentosa Unilateral

blindness, 1

Table 1 Age distribution of patients with retinitis pigmentosa

Age (years) n % Bilateral

,10 1 2.5 Low vision, 11 blindness, 12

11–20 3 7.5

21–30 7 17.5

31–40 5 12.5

41–50 11 27.5

51–60 5 12.5

.60 8 20.0

Total 40 100

Figure1 Distribution of blindness and low vision.

662 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2010:4

Dovepress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Visual impairment in retinitis pigmentosa

Table 2 Distribution of blindness and low vision according to d ifference may be explained by the delayed presentation of

patient age our patients, whose first recourse to treatment is often tradi-

Age Visual pathology tional practitioners and a tendency to come to hospital only

(years) Bilateral Unilateral when low vision and blindness are well advanced. Neverthe-

blindness Low vision blindness

less, Grover et al13 found in their US series an average age at

n (%) n (%) n (%)

0 (0.00)* 0 (0.00)* 0 (0.00)*

presentation of 41 years, which is similar to our findings.

,10

11–20 0 (0.00) 1 (33.33) 0 (0.00) In our study, 57.5% of patients had a significant bilateral

21–30 2 (28.57) 1 (14.29) 1 (14.29) decrease of visual acuity at the time of diagnosis (binocular

Clinical Ophthalmology downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 45.148.233.248 on 27-Apr-2020

31–40 1 (20.00) 3 (60.00) 0 (0.00) blindness in 30% and low vision in 27.5%). This is similar

41–50 2 (18.18) 3 (27.27) 0 (0.00)

51–60 3 (60.00) 1 (20.00) 0 (0.00)

to the data of Ukponmwan et al who reported binocular

.60 4 (50.00) 2 (25.00) 0 (0.00) blindness in 50% and low vision in 26.7% of patients in their

Total 12 (30.00) 11 (27.50) 1 (2.50) Nigerian series,7 and is also similar to the findings of Grover

et al who reported a visual acuity ,1/10 in 25% of their

patients suffering from retinitis pigmentosa,14 corresponding

studies is much lower, eg, 1/4756 in Maine, US5 and 1/3943 to severe low vision or blindness. In our series, the severity of

in Denmark.6 However, our prevalence is similar to that visual impairment appears to be correlated with patient age.

obtained by Kaya-Ganziami et al in a Congolese hospital.7 The older the subject, the more significant is the functional

In our series, retinitis pigmentosa indiscriminately impairment, and thus we are left with an average age of about

For personal use only.

affected men and women (P . 0.05), in contrast with the 40 years for people with low vision and about 50 years for

findings of Kaya-Ganziami et al in Congo and Ukponmwan people with bilateral blindness.

et al in Nigeria, where a male predominance of 63.6% and In interpreting these outcomes, it is considered that there

66.6%, respectively, has been reported.7,8 is a natural evolution of the disease whereby the patient starts

It is generally recognized that night blindness is one of to develop low vision approximately 10 years before becom-

the commonest complaints in retinitis pigmentosa,7,9–11 and ing totally blind. This is consistent with the findings of a US

the results of our study are consistent with this observation. study by Marmor15 who found far visual acuity (interpreted as

Indeed, a drop in visual acuity and night blindness were the severe low vision or blindness) to be ,1/10 in more than 50%

main reasons for consultation in our study. In addition, it of patients with retinitis pigmentosa who were aged over 50

should be noted that classical night blindness is often poorly years. The severity of visual impairment also depends on the

recognized in childhood, and might be discovered only when mode of genetic transmission. In the US, it has been shown

in-depth investigations are conducted. Our series included that patients with the clinical form of autosomal dominant

few children, but this would not affect the conclusion we retinitis pigmentosa suffer less from low vision and blindness

arrived at, ie, that a drop in visual acuity was a major cause compared with those having the X-linked recessive form of

of consultation in this series. the disease.13,16 Unfortunately, no genetic study on this issue

The average patient age of 43.3 ± 18.2 years in our series has ever been carried out in Cameroon where state-of-the-art

is older than that found by Ukponmwan et al in Nigeria science is still in its early stages.

and Tsujikawa et al in Japan, who reported an average age Retinitis pigmentosa was isolated in 67.5% of cases, and

at diagnosis of 36.7 and 35.1 years, respectively.8,12 This no case of Usher syndrome was noted. This is consistent with

a report by Kaya-Ganziami et al who found that 72.27% of

Table 3 Distribution of patients according to associated cases of retinitis pigmentosa were isolated,7 whereas Grover

pathologies et al13 found that only 47% were isolated. Associated illnesses

Associated pathologies n % were found in patients of relatively advanced age. Thus, all

Cataract 4 10.00

cases of cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and 75%

ARMD 3 7.50 of glaucoma cases were identified in patients over 40 years.

Glaucoma 3 7.50 These potentially blinding diseases might worsen the visual

High myopia 2 5.00 prognosis for these patients and consequently affect their

Isolated RP 27 67.50

Unilateral macular hole 1 2.50

quality of life. In the US, Pruett found an association between

Total 40 100.00 retinitis pigmentosa and cataracts in 46.4% of cases,17 while

Abbreviations: ARMD, age-related macular degeneration; RP, retinitis pigmentosa. Auffarth in Germany found this association in 40.7%–52.9%

Clinical Ophthalmology 2010:4 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

663

Dovepress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Eballe et al Dovepress

Table 4 Distribution of associated pathologies according to patient age

Associated Age (years) Total

pathologies* ,10 11–20 21–30 31–40 41–50 51–60 .60

Cataract 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (20.00) 1 (9.09) 1 (20.00) 1 (12.50) 4 (10.00)

ARMD 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 3 (37.50) 3 (7.50)

Glaucoma 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (9.09) 1 (20.00) 1 (12.50) 3 (7.50)

High myopia 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (14.29) 1 (20.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 2 (5.00)

Macular hole 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (14.29) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (2.50)

*n (%).

Clinical Ophthalmology downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 45.148.233.248 on 27-Apr-2020

Abbreviation: ARMD, age-related macular degeneration.

of cases, depending on the definition of retinitis pigmen- Retinitis pigmentosa is not well known to the Cameroon

tosa used.18 Furthermore, Peng in China reported a 2.3% population. Blindness which is not well explained (ie, not

glaucoma prevalence in a series of patients with retinitis cataract or glaucoma) is often attributed to a curse from, for

pigmentosa,19 which is three times lower than in our series example, a neighbor. Therefore, cases of blindness recorded

where the prevalence of glaucoma was estimated at 7.5%. in the family history of a patient suffering from retinitis

This finding provides additional evidence that chronic open pigmentosa do not enable us to make a reliable connection

angle glaucoma is more common in melanoderma subjects between this disease and other cases of blindness in the

than in any other race.20 It is also known that myopia is com- family. Consequently, any assumptions about the mode

For personal use only.

mon in retinitis pigmentosa, especially with the X-linked of transmission are questionable. Families are large, and

form, which is an even more frequent cause of consultation.21 relatives tend not to attend ophthalmologic consultations

Myopia comprised 5% of associated pathologies in our series. requested by the physician because of an inability to get time

The question arises as to whether the cases of high myopia off work, lack of interest, or lack of transport. It is therefore

that we recorded might in fact be associated with X-linked difficult to perform a thorough search for cases of retinitis

retinitis pigmentosa. Local genetic studies of this pathology pigmentosa within the same family and to determine the

in the future should throw more light on this issue. mode of transmission of the disease by either presumption

The low rate of visual field assessment would be explained or by genetic testing.

by the poor financial resources of most patients in our catch-

ment area, for whom the cost of this examination amounting Conclusion

to on average 30 Euros, would be prohibitive. Visual impairment in retinitis pigmentosa is very common

and becomes even more severe with aging. Concomitant ill-

Limitations nesses occur with age which may worsen the visual prognosis.

Limitations of this study include the inadequate technical Early screening for the disease may be the best strategy for

expertise in our unit which prevented some relevant tests its management, including both appropriate treatment and

being performed, in particular ERGs, which are of paramount genetic counseling (although it has also been shown that

importance in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. In the very more than 50% of subjects cannot confirm their heredity21).

early stages of the disease, the ERG response is either off or A study of the general population should be undertaken to

limited to a small photopic b-wave which disappears sud- identify the real prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in our

denly. There is no relationship between ERG and visual acu- area. This research should be coupled with genetic studies in

ity, in that an ERG may be off in the presence of good central order to determine the mode of transmission, which strongly

visual acuity. It is possible to conduct this examination even influences clinical expression of the disease and the visual

in children aged younger than six years, in whom the visual prognosis.

field is hard to obtain.21 On the other hand, owing to the lack

of ERG, we were not able to investigate retinitis pigmentosa Disclosure

in apparently healthy family members of affected individu- The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

als, which would have enabled us to know more about the

mode of transmission of the disease. Fluorescein angiography References

1. Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:40.

also has diagnostic and prognostic importance in retinitis 2. Bird AC. Photoreceptor dystrophies. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:

pigmentosa,21 but is not easily accessible in Cameroon. 543–562.

664 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2010:4

Dovepress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Visual impairment in retinitis pigmentosa

3. Hamel C, Griffoin JM, Bazalgette CH, et al. [Molecular genetics of 12. Tsujikawa M, Wada Y, Sukegawa M, et al. Age at onset curves of retinitis

pigmentary retinopathies: Identification of mutations in CHM, RDS, pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:337–340.

RHO, RPE65, USH2A and XLRS1 genes]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2000;23: 13. Grover S, Fishman GA, Alexander KR, et al. Visual acuity impair-

10:985–995. French. ment in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:

4. OMS/AIDE MEMOIRE. La cécité et la déficience visuelle, partie I: 1593–1600.

Informations générales. Aide mémoire n° 142, Février 1997. 14. Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, et al. Visual acuity impairment

5. Bunker CH, Berson EL, Bromley WC, Hayes RP, Roderick TH. Preva- in patients with retinitis pigmentosa at age 45 years or older.

lence of retinitis pigmentosa in Maine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97: Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1780–1785.

357–365. 15. Marmor MF. Visual loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol.

6. Haim M. Epidemiology of retinitis pigmentosa in Denmark. Acta 1990;89:692–698.

Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;233 Suppl:1–34. 16. Pearlman JT. Mathematical models of retinitis pigmentosa: A study of

Clinical Ophthalmology downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 45.148.233.248 on 27-Apr-2020

7. Kaya-Ganziami G, Nkoua JL, Mayanda HF, Makita C, Mbadinga- the rate of progress in the different genetic forms. Trans Am Ophthalmol

Mupangu H. La rétinite pigmentaire: à propos de 22 cas observés à Soc. 1979;77:643–656.

Brazzaville. Médecine d’Afrique Noire. 1994;41:297–299. 17. Pruett RC. Retinitis pigmentosa: Clinical observations and correlations.

8. Ukponmwan CU, Atamah A. Retinitis pigmentosa in Benin, Nigeria. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1983;81:693–735.

East Afr Med J. 2004;81:254–257. 18. Auffarth GU, Tetz MR, Krastel H, Blankenagel A, Völcker H E. Com-

9. Hruby K. Retinitis pigmentation. Chibret J Ophthalmol. 1983;1: plicated cataracts in various forms of retinitis pigmentosa. Type and

9–21. incidence. Ophthalmology. 1997;94:642–646.

10. Noble KG. Hereditary chorioretinal dystrophy. Freeman WR, editor. 19. Peng DW. Retinitis pigmentosa associated with glaucoma. Zhonghua

Practical Atlas of Retinal Disease and Therapy. 2nd edition. Philadel- Yan Ke Za Zhi. 1991;27:262–264.

phia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers: 1998. 20. Hamard H. Décision en Ophtalmologie. Maloine, France: Vigot

11. Heckenlively JR, Yoser SL, Friedman LH, Oversier JJ. Clinical findings publishers.1993:80–98.

and common symptoms in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 21. Godde-Jolly D, Dufier JL. Ophtalmologie Pédiatrique. Paris, France:

1988;105:504–511. Masson publishers; 1992:259–264.

For personal use only.

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

Clinical Ophthalmology is an international, peer-reviewed journal PubMed Central and CAS, and is the official journal of The Society of

covering all subspecialties within ophthalmology. Key topics include: Clinical Ophthalmology (SCO). The manuscript management system

Optometry; Visual science; Pharmacology and drug therapy in eye is completely online and includes a very quick and fair peer-review

diseases; Basic Sciences; Primary and Secondary eye care; Patient system, which is all easy to use. Visit http://www.dovepress.com/

Safety and Quality of Care Improvements. This journal is indexed on testimonials.php to read real quotes from published authors.

Submit your manuscript here: http://www.dovepress.com/clinical-ophthalmology-journal

Clinical Ophthalmology 2010:4 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

665

Dovepress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- Prevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchMuhammad RaflirNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic Pterygium Surgery Techniques and Long-Term OutcomesDocument7 pagesCosmetic Pterygium Surgery Techniques and Long-Term OutcomesrhizkyNo ratings yet

- Referral Process in Patients With Uveitis: A Challenge in The Health SystemDocument10 pagesReferral Process in Patients With Uveitis: A Challenge in The Health Systemfedcaf18No ratings yet

- OPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216Document5 pagesOPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216ppapapNo ratings yet

- Five-Year Results of ViscotrabeculotomyDocument10 pagesFive-Year Results of ViscotrabeculotomyChintya Redina HapsariNo ratings yet

- OPTH 143898 Posterior Vitreous Detachment Prevalence of and Risk Facto 091817Document7 pagesOPTH 143898 Posterior Vitreous Detachment Prevalence of and Risk Facto 091817Pangala NitaNo ratings yet

- Resiko Jatuh GlaukomaDocument5 pagesResiko Jatuh GlaukomayohanaNo ratings yet

- Kobia Acquah Et Al 2022 Prevalence of Keratoconus in Ghana A Hospital Based Study of Tertiary Eye Care FacilitiesDocument10 pagesKobia Acquah Et Al 2022 Prevalence of Keratoconus in Ghana A Hospital Based Study of Tertiary Eye Care FacilitiesEugene KusiNo ratings yet

- China Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesChina Risk FactorsNoor MohammadNo ratings yet

- Resolution of Pinguecula-Related Dry Eye Disease ADocument4 pagesResolution of Pinguecula-Related Dry Eye Disease ASylvia MtrianiNo ratings yet

- Red Eye: A Guide For Non-Specialists: MedicineDocument14 pagesRed Eye: A Guide For Non-Specialists: MedicineFapuw Parawansa100% (1)

- COMPLETODocument9 pagesCOMPLETOZarella Ramírez BorreroNo ratings yet

- Accommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationDocument7 pagesAccommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationpoppyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Mata KeratitisDocument5 pagesJurnal Mata KeratitisDayuNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadDocument5 pagesCongenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadSherry CkyNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors in Underserved Rural AreasDocument7 pagesThe Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors in Underserved Rural AreasradifNo ratings yet

- Abrar - Anterior Chamber Angle in Aniridia With and Whout GloucomaDocument5 pagesAbrar - Anterior Chamber Angle in Aniridia With and Whout Gloucomabudi haryadiNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesPattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDr. Abhishek OnkarNo ratings yet

- Schiefer 2016Document16 pagesSchiefer 2016Eric PavónNo ratings yet

- Asthenopía in ChildrenDocument9 pagesAsthenopía in ChildrenMigUel SánchezNo ratings yet

- Ocular Manifestations of Leprosy - A Clinical Study: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesOcular Manifestations of Leprosy - A Clinical Study: Original ArticleAzizah TjakradidjajaNo ratings yet

- Sakamoto 2018Document6 pagesSakamoto 2018Widya WibelNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Andi CitraDocument10 pagesJurnal Andi Citrayusti aisyahNo ratings yet

- Clinical Profile and Demographics of Glaucoma Patients Managed in A Philippine Tertiary HospitalDocument7 pagesClinical Profile and Demographics of Glaucoma Patients Managed in A Philippine Tertiary HospitalPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- JWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217Document6 pagesJWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217ppapapNo ratings yet

- Dry Eyes and Digital Devices 1Document11 pagesDry Eyes and Digital Devices 1Koas HAYUU 2022No ratings yet

- Ukponmwan 2004Document4 pagesUkponmwan 2004ppapapNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Retinitis Pigmentosa: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument8 pagesUnilateral Retinitis Pigmentosa: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureWidyawati SasmitaNo ratings yet

- 971 FullDocument3 pages971 Fullوسام الرعويNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors Among Adults Attending at A Tertiary Care Hospital - A Retrospective StudyDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Errors Among Adults Attending at A Tertiary Care Hospital - A Retrospective StudyyuyuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Asli Word - Intan MalafinaDocument11 pagesJurnal Asli Word - Intan MalafinaIntanNo ratings yet

- Progression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent CohortDocument6 pagesProgression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent Cohortfarras fairuzzakiahNo ratings yet

- Detection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanDocument8 pagesDetection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanPuskesmas Purwokerto SelatanNo ratings yet

- Prospective Evaluation of Visual Function For Early Detection of Ethambutol ToxicityDocument5 pagesProspective Evaluation of Visual Function For Early Detection of Ethambutol Toxicitysatyagraha84No ratings yet

- Corneal Laceration Caused by River Crab: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveDocument4 pagesCorneal Laceration Caused by River Crab: Clinical Ophthalmology Dovesiti rumaisaNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument9 pagesGlaucomaREGINE YEO ZHI SHUENNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainIndah Nur LathifahNo ratings yet

- Causes and Correction Dissatisfaction After ImpDocument6 pagesCauses and Correction Dissatisfaction After ImpSATYAJITSINH GOHILNo ratings yet

- Sympathetic Ophthalmia After Vitreoretinal Surgery: A Report of Two CasesDocument11 pagesSympathetic Ophthalmia After Vitreoretinal Surgery: A Report of Two CasesAlexander RezaNo ratings yet

- 227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Document5 pages227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Ayele BizunehNo ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2020 041854Document8 pagesBmjopen 2020 041854MufassiraturrahmahNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study of The Association Between Fuchs and Glaucoma - CopieDocument5 pagesA Retrospective Study of The Association Between Fuchs and Glaucoma - CopiefellaarfiNo ratings yet

- Video Interpretation and Diagnosis of Pediatric Amblyopia and Eye DiseasseDocument7 pagesVideo Interpretation and Diagnosis of Pediatric Amblyopia and Eye DiseasseDinda Ajeng AninditaNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Ophthalmology Case ReportsDocument6 pagesAmerican Journal of Ophthalmology Case ReportsPuput Anistya HarianiNo ratings yet

- Eye 2008158Document10 pagesEye 2008158KillNoiseNo ratings yet

- Optimal Management of Pediatric Keratoconus: Challenges and SolutionsDocument9 pagesOptimal Management of Pediatric Keratoconus: Challenges and SolutionsJesus Rodriguez NoriegaNo ratings yet

- Exopthal 8Document7 pagesExopthal 8Perdana SihiteNo ratings yet

- Uveitic Glaucoma Management With Recurrent Uveitis EpisodeDocument6 pagesUveitic Glaucoma Management With Recurrent Uveitis EpisodeLina Shabrina QoribNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Uveitis in The Mid-Atlantic United States: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveDocument6 pagesTraumatic Uveitis in The Mid-Atlantic United States: Clinical Ophthalmology DoveRanhie Pen'ned CendhirhieNo ratings yet

- Intermittent Exotropia Our Experience in Surgical Outcomes 2155 9570 1000722Document3 pagesIntermittent Exotropia Our Experience in Surgical Outcomes 2155 9570 1000722Ikmal ShahromNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Ultrasonography and Histologic ExaminationDocument13 pagesComparison of Ultrasonography and Histologic ExaminationLeonardo A. Muñoz DominguezNo ratings yet

- OPTH 118409 Undesirable Systemic Side Effects of Ophthalmic Drops From T 120716Document9 pagesOPTH 118409 Undesirable Systemic Side Effects of Ophthalmic Drops From T 120716Optm Abdul AzizNo ratings yet

- A Rare Complication of Combined Oral Contraceptives (Cocs) : Optic NeuritisDocument3 pagesA Rare Complication of Combined Oral Contraceptives (Cocs) : Optic NeuritisGufront MustofaNo ratings yet

- Visual Outcomes Following Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) in Wangaya HospitalDocument4 pagesVisual Outcomes Following Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) in Wangaya HospitalKrisnhalianiNo ratings yet

- Safety of Cetirizine Ophthalmic Solution 0.24% For The Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis in Adult and Pediatric SubjectsDocument11 pagesSafety of Cetirizine Ophthalmic Solution 0.24% For The Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis in Adult and Pediatric SubjectsrismaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Tear Film EvaluationDocument5 pagesThesis Tear Film EvaluationKjhnNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyDocument4 pagesClinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyFi NoNo ratings yet

- Prevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDocument10 pagesPrevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDaniel AsmareNo ratings yet

- Bjophthalmol 2020 317832Document5 pagesBjophthalmol 2020 317832kenly chandraNo ratings yet

- OPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216Document5 pagesOPTH 107890 Clinical Presentation and Visual Status of Retinitis Pigment - 082216ppapapNo ratings yet

- JWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217Document6 pagesJWestAfrCollSurg10230-7573758 210217ppapapNo ratings yet

- Hartong 2006Document15 pagesHartong 2006ppapapNo ratings yet

- Ukponmwan 2004Document4 pagesUkponmwan 2004ppapapNo ratings yet

- David Abel: As Pandemic Wears On, Despair at Epicenter of Addiction Crisis Deepens byDocument4 pagesDavid Abel: As Pandemic Wears On, Despair at Epicenter of Addiction Crisis Deepens byCourtney CrowleyNo ratings yet

- Shillings Dialectical LensDocument3 pagesShillings Dialectical Lensapi-399928223No ratings yet

- NeurotransmissionDocument3 pagesNeurotransmissionElilta MihreteabNo ratings yet

- Scalp Block For Awake Craniotomy Lidocaine-BupivacDocument10 pagesScalp Block For Awake Craniotomy Lidocaine-BupivacremediNo ratings yet

- Maternity, Wejdan NDocument26 pagesMaternity, Wejdan NirrajawahirNo ratings yet

- Activity Date Venue Responsibility Resources OutputDocument3 pagesActivity Date Venue Responsibility Resources OutputLahiru DilshanNo ratings yet

- The Wii Club: Gaming For Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese YouthDocument4 pagesThe Wii Club: Gaming For Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese YouthAXEL FRANK ALMONTE CUBANo ratings yet

- Artikel Rev 1Document19 pagesArtikel Rev 1ChrisnaArdhyaMedikaNo ratings yet

- USP General Chapter : Pharmaceutical Compounding - Sterile PreparationsDocument37 pagesUSP General Chapter : Pharmaceutical Compounding - Sterile PreparationsRRR1No ratings yet

- How To Manage Cortisol Levels With Maca RootDocument19 pagesHow To Manage Cortisol Levels With Maca RootCalvin McDuffieNo ratings yet

- Chapter III Lesson 2 BiodiversityDocument48 pagesChapter III Lesson 2 BiodiversityMichael James CaminoNo ratings yet

- Amazing Science 5 - Unit 4Document1 pageAmazing Science 5 - Unit 4Nguyễn Khương LinhNo ratings yet

- Point of Care Risk Assessment (PCRA) : Assess The Task, The Patient and The Environment Prior To Each Patient InteractionDocument1 pagePoint of Care Risk Assessment (PCRA) : Assess The Task, The Patient and The Environment Prior To Each Patient InteractionchrisNo ratings yet

- اسئلة وزارة الصحة للالتحاق ببرنامج الاقامة والامتيازDocument68 pagesاسئلة وزارة الصحة للالتحاق ببرنامج الاقامة والامتيازAhmad HamdanNo ratings yet

- Notes 1Document5 pagesNotes 1logonautNo ratings yet

- Alternative Carriers in Dry Powder InhalerDocument9 pagesAlternative Carriers in Dry Powder InhalerApoorva KNo ratings yet

- Sindrom Uko Ene Osobe (Moersch-Woltman) : Lije Vjesn 2010 132:110-114Document5 pagesSindrom Uko Ene Osobe (Moersch-Woltman) : Lije Vjesn 2010 132:110-114bimtolaNo ratings yet

- Jumbled Letter Game WoundDocument12 pagesJumbled Letter Game WoundDyan Nuli AngrengganiNo ratings yet

- Basic Coronary Angiography All SlidesDocument55 pagesBasic Coronary Angiography All SlidesSaud ShirwanNo ratings yet

- Angeles University Foundation: College of Nursing Nursing Care PlanDocument2 pagesAngeles University Foundation: College of Nursing Nursing Care PlanJohn CuencoNo ratings yet

- Upper Motor Neuron Vs Lower Motor Neuron AtfDocument4 pagesUpper Motor Neuron Vs Lower Motor Neuron AtfRishi VermaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Animal HealthDocument9 pagesModule 5 Animal HealthArlyn Joy RiñoNo ratings yet

- English8 q1 Mod5 ExpressingEmotionalResponseandReactions v3-2Document37 pagesEnglish8 q1 Mod5 ExpressingEmotionalResponseandReactions v3-2Aljerr Laxamana100% (3)

- Cbse Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper - 1 SAIDocument10 pagesCbse Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper - 1 SAIKaran KumarNo ratings yet

- Caring For Stroke PatientsDocument4 pagesCaring For Stroke PatientsshydeeNo ratings yet

- Clean Water and SanitationDocument5 pagesClean Water and SanitationSarah azizahNo ratings yet

- قرار مجلس الوزراء رقم 28 بشأن نظام نقل الدمDocument44 pagesقرار مجلس الوزراء رقم 28 بشأن نظام نقل الدمAbood dot netNo ratings yet

- Science 10 Q3 Module 3Document26 pagesScience 10 Q3 Module 3090406No ratings yet

- Review Related Studies Related To Teenage Pregnancy (Foreign)Document44 pagesReview Related Studies Related To Teenage Pregnancy (Foreign)ruth ann solitarioNo ratings yet

- Short Cases in MedicineDocument30 pagesShort Cases in MedicineselamuNo ratings yet