Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Huttner 2009

Uploaded by

kevin ortegaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Huttner 2009

Uploaded by

kevin ortegaCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Malignant middle cerebral artery infarction: clinical

characteristics, treatment strategies, and future perspectives

Hagen B Huttner, Stefan Schwab

Space-occupying, malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarctions are still one of the most devastating forms of Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 949–58

ischaemic stroke, with a mortality of up to 80% in untreated patients. An early diagnosis is essential and depends on Department of Neurology,

CT and MRI to aid the prediction of a malignant course. Several pharmacological strategies have been proposed but University of Erlangen,

Germany (H B Huttner MD,

the efficacy of these approaches has not been supported by adequate evidence from clinical trials and, until recently,

S Schwab MD)

treatment of malignant MCA infarctions has been a major unmet need. Over the past 3 years, results from randomised

Correspondence to:

controlled trials and their pooled analyses have provided evidence that an early hemicraniectomy leads to a substantial Stefan Schwab, Department of

decrease in mortality at 6 and 12 months and is likely to improve functional outcome. Hemicraniectomy is now in Neurology, University of

routine use for the clinical management of malignant MCA infarction in patients younger than 60 years of age. Erlangen-Nuremberg,

Schwabachanlage 6,

However, there are still important questions about the individual indication for decompressive surgery, particularly

90154 Erlangen, Germany

with regard to the ideal timing of hemicraniectomy, a potential cut-off age for the procedure, the hemisphere affected, stefan.schwab@uk-erlangen.

and ethical considerations about functional outcome in surviving patients. de

Introduction malignant MCA infarctions. We then assess the evidence

Although space-occupying, malignant middle cerebral for current treatment strategies, with a particular focus

artery (MCA) infarction has not been defined as a distinct on hemicraniectomy and the implications of the recent

disorder, its definition is usually based on clinical trials. Questions about the individual indication for

presentation, typical clinical course, and neuroradiological hemicraniectomy in specific patients with malignant

findings.1 Patients with subtotal or complete MCA MCA infarction are discussed and we give our perspective

infarctions typically present with hemiparalysis, severe on future clinical studies.

sensory deficits, head and eye deviation, hemi-inattention,

and, if the dominant hemisphere is involved, global Epidemiology and clinical features

aphasia.2,3 Patients with malignant MCA infarctions show Generally, subtotal or complete MCA infarctions are

a progressive deterioration of consciousness over the first found in up to 10% of patients with supratentorial

24–48 h and commonly have a reduced ventilatory drive, ischaemia.4,15 The yearly incidence of a malignant acute

requiring mechanical ventilation.4,5 Malignant MCA ischaemic stroke is between about 10 and 20 per

infarctions constitute between 1% and 10% of all 100 000 people.4,16,17 Compared with other patients with

supratentorial ischaemic strokes,4 and treatment of this ischaemic stroke, substantially fewer of those who have

disorder has been a major unsolved problem in malignant MCA infarction have a history of ischaemic

neurocritical care.6,7 Several pharmacological treatment stroke and women are more likely to be affected.16,18

approaches, such as osmotic therapy, steroids, Moreover, patients with malignant MCA infarction seem

hyperventilation, barbiturates, and trishydroxymethyl- to be younger and more commonly have involvement of

aminomethane (THAM) buffers, have been proposed to the anterior choroidal artery than patients who do not

reduce cerebral oedema formation, but so far none of develop space-occupying infarctions.19

these therapeutic strategies has been supported by The aetiology of malignant MCA infarctions is mostly

adequate evidence of efficacy from clinical trials.8–10 due to thrombosis or embolic occlusion of either the

Between 2007 and 2009, data from randomised trials internal carotid artery or the proximal MCA. Depending

were published that provided evidence of a substantial on anatomical variances, the anterior and/or posterior

decrease in mortality of patients who underwent cerebral artery territories might be involved

decompressive surgery (hemicraniectomy) for treatment concomitantly.19 Anatomical variances and pathological

of space-occupying MCA infarction.5,11,12 Meta-analyses findings that predispose an individual to a malignant

supported this finding;5,13 however, as some primary MCA infarction include abnormalities of parts of the

outcome measures were neutral, there are fundamental ipsilateral circle of Willis (mainly a hypoplasia or an

questions about trial design and interpretation and about atresia) and an insufficient number and calibre of

the benefits of this surgery on functional outcome in leptomeningeal collateral vessels that are available for

surviving patients. Moreover, although the survival collateralisation.19,20

benefit from hemicraniectomy is undisputed, the Clinical assessment of patients with a malignant MCA

functional outcome of surviving patients treated with infarction is based on the National Institutes of Health

this procedure is variable and often poor, raising stroke scale (NIHSS); the latter has been shown to

important ethical considerations. underestimate the severity of infarctions of the

In this Review, we briefly outline the epidemiology, non-dominant hemisphere.21 The NIHSS score typically

clinical characteristics, and imaging findings in exceeds 16–20 if the dominant hemisphere is involved,

www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009 949

Review

and is more than 15–18 in malignant MCA infarctions the ipsilateral anterior or posterior cerebral arteries can

of the non-dominant hemisphere.5,11,12 Within occur concomitantly with MCA infarctions. The definite

24–48 h of stroke, there is usually a progressive infarction volume visualised on MRI is evident as

deterioration in the patient’s level of consciousness hyperintense lesions on FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion

owing to the commonly associated serious brain swelling recovery) sequences; however, in the hyperacute stages,

that develops within 1–5 days after stroke.7,21 The resulting even diffusion-weighted sequences can be used to reliably

increased intracranial pressure and tissue shifts lead to predict a malignant MCA infarction if the lesion volume

further destruction of formerly healthy brain tissue, is more than 145 cm³.11,36,37 Analysis of the permeability of

giving rise to the term malignant MCA infarction.4 These the blood–brain barrier by use of data from MRI, PET,

large cerebral infarctions often result in severe shifting of and SPECT (single photon emission computed

midline structures with subsequent uncal or even tomography) can be used to predict a space-occupying

transtentorial herniation,22 and thus have been associated course of MCA infarction;38–40 these new approaches,

with a poor prognosis in more than 80% of cases.23–26 however, need further prospective evaluations.1

The pathophysiological processes that lead to a

malignant MCA infarction are not yet completely Conservative management

known.27–30 As in stroke in general, the ischaemic cascade Pharmacological approaches

mainly consists of an excitatory phase, followed by Patients with large, space-occupying MCA infarctions

peri-ischaemic depolarisations that lead to inflammation, require immediate intensive care on a specialised

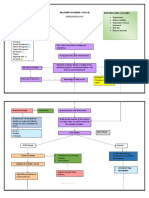

apoptosis, and, finally, oedema formation (figure 1).31,32 neurocritical care unit. Sedation, intubation, and

mechanical ventilation are often indicated early, and even

Imaging and prediction of a malignant course electively once the malignant course of the disease has

Cranial CT is widely used for the diagnosis and monitoring been verified, to prevent aspiration and to allow invasive

of patients with malignant MCA infarction (figure 2).1,3,33,34 treatment to be started.9,41 There are many pharmacological

However, as repeated CT imaging up to the first 3 days approaches to the prevention and management of the

after stroke onset might be necessary to determine the developing brain oedema.9 Treatment with osmotic

definite area of infarction and the extent of any associated compounds, such as mannitol, glycerol, and hypertonic

brain swelling and midline shift, several studies have saline, reduce increased intracranial pressure and seem

focused on identifying variables that allow an early to affect outcome, but their efficacy has not yet been

prediction of a malignant course by use of multi-slice CT, proven in randomised clinical trials.9,10 Unfortunately, all

CT angiography, CT perfusion, and MRI.34–37 Generally, a other approaches, such as barbiturates, hyperventilation,

neuroradiological definition of a malignant MCA head elevation, THAM buffers, indometacin, steroids,

infarction assumes that at least two-thirds of the MCA and furosemide, are not supported by adequate evidence

territory is affected. Other authors predict a malignant of efficacy and these treatment strategies might even be

course with development of severe oedema if more than detrimental.9,42–44 Case series on outcome of patients with

50% of the rostral MCA territory and the basal ganglia malignant MCA infarctions who received maximum

show ischaemic alterations.12,37 Additionally, infarctions of conservative treatment did not report significant clinical

effects of these procedures.4,23

Intracranial blood Hypothermia

CSF

There is a strong association between fever and a poor

outcome after stroke.45 Consequently, moderate hypo-

Change in thermia with target temperatures between 33°C and 35°C,

intracranial achieved with endovascular catheters, is a promising

Intracranial pressure

pressure

approach for neuroprotection in patients with large MCA

Brain tissue infarctions.46,47 Hypothermia reduces the cerebral

Change in volume

metabolic rate and stabilises the blood–brain barrier.

Decreasing the formation of free radicals and the release

of excitatory neurotransmitters results in less brain

oedema and attenuates the postischaemic inflammatory

response and apoptosis.48 Results from various animal

studies have been confirmed by data from clinical

Intracranial volume

observational studies (although only a few patients

Figure 1: Brain oedema formation treated with moderate hypothermia were analysed),

Schematic diagram of cerebral compliance. An increase in oedematous brain tissue requires a compensatory which indicate both a reduced mortality and a good

decrease in the other two physiological compartments contained in the skull: intravascular blood and CSF. If these

limited compensatory mechanisms are not sufficient, even a small increase in the intracranial volume might result

functional outcome in the surviving patients.48–54 In light

in a substantial rise in intracranial pressure. Similarly, even a small decrease in brain oedema can substantially of the strong association between fever and poor outcome

lower the intracranial pressure. after stroke,45 these results with hypothermia are

950 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009

Review

promising; however, the findings should be considered

A B

as preliminary because there is no evidence from

randomised trials on the efficacy of cooling as a treatment

for malignant MCA infarction.

Decompressive surgery

Surgical techniques

Decompressive surgery is based on a hemicraniectomy

in combination with a duraplasty.55 After incision of the

skin in the shape of a question mark, a bone flap that has

a diameter of at least 12 cm is removed, including parts

of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital squama.56,57

The removed bone flap must be of a sufficient size to

prevent additional ischaemic lesions.58 After opening of

the dura, a dural patch is inserted, which usually consists

of homologous periosteum or a temporal fascia. C D

Ischaemic brain tissue is not resected. An intracranial

pressure probe can be inserted for further monitoring.

After 6 weeks and up to 6 months after removal, the

stored bone flap, or an artificial replacement, is used for

reconstituting cranioplasty.59

The main aim of decompressive surgery is to remove

part of the cranium to enable outward swelling of

ischaemic brain tissue without compromising healthy

brain areas by midline shift and ventricular

compression.55,60 The normalising of increased intra-

cranial pressure levels results in raised cerebral blood

flow and improved cerebral perfusion pressure, which

leads to better oxygenation of brain tissue that is still

Figure 2: Brain imaging findings before and after hemicraniectomy in malignant MCA infarction

healthy (figure 3).10,61–63

(A) Axial cranial CT 7 h after stroke onset. Arrows indicate the margins of the infarction. (B) Axial

diffusion-weighted MRI in the acute phase of malignant MCA infarction. (C) and (D) Axial CT on day 2 after

Experimental and clinical observational studies symptom onset after hemicraniectomy. Note that despite decompressive surgery, a compression of the ventricular

Various animal studies have been undertaken to system with slight midline shifting (C; axial CT at the level of the basal ganglia) and a beginning outward swelling

(D; axial CT at the supraventricular level) of the ischaemic brain tissue is evident. Images courtesy of the

experimentally investigate the potential benefits of

Department of Neuroradiology, University of Erlangen, Germany. MCA=middle cerebral artery.

surgical decompression. Craniotomy was proven to

correlate with early reperfusion and decreased final

infarction volume.64 However, this effect might be immediate hypothermia might further improve outcome:

limited to an intervention done early after vessel although reporting on only a few patients (n=25), a study

occlusion.65 In rat studies, a decrease in mortality and by Els and colleagues83 indicated a statistical trend

improved clinical outcome was reported, particularly towards a better functional outcome in terms of NIHSS

when decompressive surgery was combined with and Barthel scores with the combination of

moderate hypothermia.64–67 hemicraniectomy and hypothermia than with

The encouraging findings from animal studies of a hemicraniectomy alone. A larger prospective multicentre

decrease in mortality were supported by clinical trial on the possible benefits of this treatment combination

investigations. Although mainly retrospective and of an is therefore warranted.

observational design, more than 80 reports have analysed Several risk factors that predict mortality and poor

the possible efficacy of hemicraniectomy in routine functional outcome have been identified, age being the

clinical settings with regard to mortality, functional strongest one (identified in a meta-analysis by Gupta and

outcome, and quality of life.26,68–82 Results from most of colleagues79), followed by a low Glasgow coma scale score

these studies have provided evidence for reduced on admission, involvement of territories other than the

mortality in patients who underwent decompressive MCA area, anisocoria, early clinical deterioration,

surgery. However, the control patients used in some coronary artery disease, and internal carotid artery

studies were poorly matched, as they were substantially occlusion.26,68,75,79,84–87 There are few studies on the long-term

older, had more severe comorbidities, or had been treated outcome and quality of life of patients who have received

months or years before the study patients. The findings hemicraniectomy.70–72,82,88 The available data indicate that

of functional outcome and quality of life are inconclusive. the average quality of life after malignant MCA infarction

Combined therapy with decompressive surgery and is acceptable, and retrospective agreement to hemi-

www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009 951

Review

A B 24 h of symptom onset and who were younger than

60 20

55 years of age. The primary endpoint in this trial was

functional outcome after 6 and 12 months based on the

50 modified Rankin scale (mRS) score, which was

Intracranial pressure (mm Hg) 15 dichotomised between 0–3 and 4–6, and interim analyses

40 were done after every four patients. Secondary endpoints

PBR O2 (mm Hg)

included survival and mRS at 6 and 12 months. Surgery

30 10

had to be undertaken within 30 h after symptom onset.

20 After randomisation of 38 patients, the data safety

5 monitoring committee recommended discontinuation of

10 the study because of a planned pooled analysis with the

other European trials (see below). At that time, there was

0 0

a significant difference in survival: five of 20 patients who

Craniotomy Opening of the dura received hemicraniectomy died compared with 14 of

Figure 3: Decompressive surgery and intracranial pressure

18 patients treated conservatively (p<0·01), with an

(A) Intra-operative multi-slice CT. Bone window three-dimensional reconstruction after removal of the bone flap absolute risk reduction of more than 52%. The functional

during hemicraniectomy. Image courtesy of Alfred Aschoff, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Heidelberg, outcome analysis did not reach significance both at the

Germany. (B) Curve of intracranial pressure (red) and brain tissue oxygenation (PBR O2; blue). Note that the essential 6-month (mRS ≤3 in 5 patients who received hemi-

decrease in intracranial pressure and elevation in brain tissue oxygenation partly occurs after craniotomy, and to a

greater extent after opening of the dura. Adapted from Gruber and colleagues,61 with permission from

craniectomy vs 1 patient who was treated conservatively;

Krause & Pachernegg. p=0·18) and 12-month (mRS ≤3 in 10 vs 4; p=0·10) follow-

up examinations.11

craniectomy is high in both patients and their relatives.5,72 The German DESTINY trial12 was an open, controlled,

However, depression is commonly present in surviving prospective, randomised, multicentre study that included

patients.71,80 This finding was confirmed in the recently patients with a malignant MCA infarction who were

published HAMLET (Hemicraniectomy After Middle diagnosed within 36 h of symptom onset and who were

cerebral artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema younger than 60 years of age. Patients were randomised

Trial) study (n=32); patients who underwent surgical to receive either surgical plus best medical treatment or

decompression as well as those who were treated best conservative treatment alone, including hypothermia.

conservatively showed symptoms of depression. A higher However, the option of hypothermia was not used in any

number of patients in the hemicraniectomy group had a of the included patients. DESTINY was based on a

score of 7 or more on the Montgomery and Asberg sequential design: mortality after 30 days was assessed as

depression rating scale than did those who were treated a first endpoint, and randomisation was planned to

conservatively, although the difference was not statistically continue until statistical significance for this endpoint

significant (18 vs 7; p=0·22).5 was reached. Enrolment of patients would then be

interrupted until data on the primary endpoint (6-month

Randomised clinical trials functional outcome based on dichotomised mRS scores

Following on from the promising results of experimental, of 0–3 vs 4–6) had been analysed. Depending on the

observational, and non-randomised studies, there have observed difference in functional outcome, the final

been five randomised controlled trials initiated since sample size would be recalculated for a second explorative

2000, of which three European trials and their pooled trial stage. As a secondary endpoint, dichotomisation of

analyses have been published over the past 3 years.5,11–13 patients into those who had a score of mRS 0–4 after

Official data from the American HeADDFIRST study 1 year versus those who had an mRS score of 5 or 6 was

(Hemicraniectomy and Durotomy Upon Deterioration planned. A significant difference in mortality was seen

From Infarction Related Swelling Trial) and the Philippine after inclusion of 32 patients. The intention-to-treat

HeMMI trial (Hemicraniectomy For Malignant Middle analysis revealed that after 30 days, two of 17 patients in

Cerebral Artery Infarcts) are awaited; HeADDFIRST has the hemicraniectomy arm and eight of 15 patients in the

been completed but not yet published officially, and conservative treatment group had died (p=0·02). The

HeMMI is still recruiting patients.89 The European trials consecutive functional outcome analysis did not show

were DECIMAL (DEcompressive Craniectomy In significant differences (eight patients in the surgical arm

MALignant middle cerebral-artery infarcts),11 DESTINY versus four in the conservative treatment group had an

(DEcompressive Surgery for the Treatment of malignant mRS score of 0–3; p=0·23). The secondary outcome

INfarction of the middle cerebral arterY),12 and comparison revealed a significant difference in favour of

HAMLET.5 surgical treatment (13 in the surgical arm versus five

The French DECIMAL trial11 was an open, prospective, conservatively treated patients had an mRS score of 0–4;

randomised, multicentre study with blinded evaluation p=0·01), as did the distribution of the mRS scores

of the primary endpoint. DECIMAL started enrolment in (p=0·04) at 12 months. After calculation of the sample

2001 and included patients who were diagnosed within size needed for attaining the primary endpoint (at least

952 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009

Review

188 randomised patients), DESTINY was stopped because functional outcome, the pooled analysis indicated that

of ethical concerns.12 patients who underwent decompressive surgery more

The Dutch HAMLET trial5 included patients who were often had mRS scores of 3 or less (43% vs 21%; p=0·014;

diagnosed within 96 h after symptom onset and who absolute risk reduction of 23%) and mRS scores of 4 or

were younger than 60 years of age. The primary endpoint less (75% vs 24%; p<0·01; absolute risk reduction of

was the functional outcome after 12 months, dichotomised 51%). These data formed the basis of a calculation of

according to mRS scores (0–3 vs 4–6). Among other the numbers needed to treat (NNT) with hemi-

secondary endpoints, case fatality and a dichotomised craniectomy to achieve a successful outcome. The NNT

functional outcome analysis (mRS 0–4 vs 5 or 6) were for survival was two, irrespective of functional outcome,

used. After obtaining the 1-year follow-up outcome data four for an mRS score of 3 or less, and two for an mRS

for 50 patients (at that time 64 patients had been score of 4 or less. Moreover, this positive effect of

recruited), the data monitoring committee recommended surgery was highly consistent across the three trials.

discontinuation of the trial because it seemed unlikely However, there was no difference in the benefit of

that a statistically significant difference between the surgery for any of the predefined subgroup analyses for

treatment groups would be seen for the primary outcome age (older or younger than 50 years), presence of

measure. Additionally, for the secondary outcome aphasia, and time to randomisation (within or beyond

measure of function on the mRS, scores were not 24 h).13

significantly different between the two groups. However, After completion of HAMLET in 2009, an updated

surgical decompression was associated with a decrease meta-analysis, which included all patients from DESTINY,

in mortality (seven vs 19; p=0·002), with an absolute risk DECIMAL, and HAMLET who were randomised within

reduction of 38%.5 48 h after stroke onset, focused on case fatality rate and

functional outcome after 12 months.5 Of the 109 patients

Pooled analyses and meta-analyses of DECIMAL, analysed, 58 had been assigned to receive surgery and 51

DESTINY, and HAMLET to receive conservative treatment. With regard to

In 2007, the results of a pooled analysis of the three mortality, the absolute risk reduction with surgical

European trials (DESTINY, DECIMAL, and 23 patients decompression compared with conservative treatment

from the then-ongoing HAMLET trial who had received

surgery within 48 h after symptom onset) were mRS=2 mRS=3 mRS=4 mRS=5 Death

A DECIMAL11

published.13 For this pooled analysis, a maximum time

window of 48 h from stroke onset to treatment was Conservative treatment (n=18) 4 14

adopted. Given the different outcome data of the Decompressive surgery <30 h (n=20) 3 7 5 5

three trials, as shown by the wide distribution of scores

on the mRS (figure 4),5,11,12 the importance of the

B DESTINY12

collaboration of the European groups becomes clear: this

pooled analysis had been prospectively planned at a time Conservative treatment (n=15) 1 3 1 2 8

when each of the studies was still ongoing and, therefore, Decompressive surgery <36 h (n=17) 4 4 5 1 3

this analysis could provide strong evidence of reduced

mortality at a very early stage.13,90 Otherwise, if the

C HAMLET5

investigators had waited until the end of enrolment for

each study, the final results might have been less certain Conservative treatment (n=32) 3 5 5 19

or new problems might have emerged (see below).5,14,90 Decompressive surgery <96 h (n=32) 1 7 11 6 7

Different treatment algorithms for conservatively treated

patients might have contributed to the varying outcome D Meta-analysis13

findings of the three trials (eg, the control group in

HAMLET received conservative management on stroke Conservative treatment (n=42) 1 8 1 2 30

units, whereas best medical treatment was provided on Decompressive surgery <48 h (n=51) 7 15 16 2 11

neurocritical care units in DESTINY).

The outcome measures of this pooled analysis were 0 20 40 60 80 100

mortality and functional outcome (mRS) at 1 year, Patients (%)

dichotomised into mRS scores of 0–3 versus 4–6

Figure 4: Comparison of outcome data 12 months after malignant MCA infarction as distributions of scores

(mortality) and 0–4 versus 5 or 6 (functional outcome).13 on the mRS (best medical treatment versus hemicraniectomy)

Of the 93 patients included, 51 had received Results of the DECIMAL trial11 (A), DESTINY trial12 (B), HAMLET trial5 (C), and a pooled analysis of patients from

hemicraniectomy and 42 had been assigned to receive these trials* who received surgery within 48 h after symptom onset (D).13 For interpretation see text. *23 patients

conservative treatment. There was a significantly lower from HAMLET. DECIMAL=DEcompressive Craniectomy In MALignant middle cerebral-artery infarcts.

DESTINY=DEcompressive Surgery for the Treatment of malignant INfarction of the middle cerebral arterY.

case fatality rate in the surgical group than in the HAMLET=Hemicraniectomy After Middle cerebral artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema Trial. MCA=middle

conservative treatment arm (29% vs 78%; p<0·01), with cerebral artery. mRS=modified Rankin scale. Subparts A and B are adapted from Vahedi et al11 and Jüttler et al,12

an absolute risk reduction of 50%. With regard to the with permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009 953

Review

alone was 49·9% (95% CI 33·9–65·9), confirming the mRS ≥4) who is intellectually able and who, for example,

previously reported NNT of two for prevention of death. can experience his child growing up in a sound family

There was an absolute risk reduction of 41·9% environment might subjectively interpret this clinical

(25·2–58·6) for an outcome measure of more than 4 on status as more favourable than a patient with aphasia and

the mRS when treated with hemicraniectomy, indicating depression who reached an mRS score of 3 or less. The

an NNT of two. However, the analysis of functional out- discussion of functional outcome in terms of what is

come revealed a non-significant benefit of surgical ethical or not is important in light of the possibilities of

decompression: 23 of 58 patients who received hemi- hemicraniectomy. Before surgical decompression was

craniectomy versus 12 of 51 who received conservative available, malignant MCA infarction was a disorder with

treatment had an mRS score of 3 or less (absolute risk a high mortality rate. As this life-saving procedure results

reduction of 16·3%; 95% CI –0·1 to 33·1; NNT of six). in about 40% of survivors becoming disabled, there are

likely to be differences in opinion among clinicians,

Open questions and future perspectives patients, and their families as to the value of this

Functional outcome treatment.

The above randomised controlled trials and their pooled

analyses have provided clear evidence that the survival Timing of surgery

rate after malignant MCA infarction was substantially One of the most urgent questions regarding surgical

higher in patients who received surgical decompression decompression for treatment of malignant MCA

instead of conservative treatment. There is no doubt infarction concerns the optimum time-point for surgery.

that this finding is of major importance and has In principle, there are two contrary approaches: either to

changed, and will further affect, routine management of operate as soon as diagnosis of a complete MCA infarction

malignant MCA infarction. However, interpretation of is made or to wait until a possible development occurs

the data on functional outcome, measured as mRS such as further clinical deterioration, midline shift on

scores below or above 3 or 4, is more difficult. One of brain imaging, increased intracranial pressure values, or

the key questions is whether an mRS score of 4 is even signs of herniation.92 In light of a variable clinical

considered to be a favourable outcome (while an mRS course (some patients develop fatal brain oedema early,

score of 5 is seen as unfavourable). One could even whereas other patients do not show severe brain swelling

argue that the decreased mortality after hemicraniectomy for several days), identification of those patients who are

is achieved at the expense of functionality for surviving at risk of developing an early malignant course must be

patients (figure 4). In other words, while the few patients done as soon as possible. However, more research is

who survive a malignant MCA infarction and who needed to understand the factors that promote or protect

receive conservative treatment have a good functional against malignant brain oedema formation.1,60 Further

outcome, the many more survivors who receive experimental studies on reperfusion, free radicals,

decompressive surgery are more likely to have functional prostaglandins, arachidonic acid, and leukotrienes,9,10,27,40,93

dependency with impaired quality of life and commonly and with novel imaging approaches, including MRI,

have depression.91 might be helpful in this regard.28,36,37

Therefore, whether an mRS score of 4 (moderately Published data about the timing of hemicraniectomy

severe disability; unable to walk without assistance and are derived mainly from contradictory observational

unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance) studies (the three European trials did not satisfactorily

can be interpreted as a favourable outcome is of great address this matter). For example, Mori and colleagues75

importance. This question should probably be answered and Woertgen and co-workers70 retrospectively compared

only by the individual patients and their caregivers. One mortality and outcome of patients who received

of the main irresolvable problems is that many patients hemicraniectomy either early after diagnosis of complete

in the acute situation cannot state their preferences and MCA infarction or at a delayed point when additional

cannot be adequately advised of treatment options. symptoms of brain swelling occurred. Both studies

Moreover, the rehabilitation potential of those patients— concluded that there were benefits of early surgery with

which, if known, would probably influence whether to regard to decreased mortality (4·8% vs 17·2% after

operate or not—is linked to their social, familial, and 1 month, 19·1% vs 27·6% after 6 months,75 and 16% vs

economic support. To obtain data that would aid decision 39% after a mean follow-up time of 30 months70); however,

making, future research on decompressive surgery the data on functional outcome were inconclusive. The

should concentrate on identifying predisposing factors finding of a reduced mortality was also reported by Schwab

for survival with a poor outcome (mRS of 4 or 5). and colleagues,68 who compared early surgery (within

The mRS mainly reflects motor function and 24 h) with delayed hemicraniectomy (after 48 h): as well as

dependency, a general categorisation of outcome. a reduced case fatality rate (16% vs 34%), there was a trend

Whether the mRS is the appropriate score (rather than towards a better clinical outcome in patients who had early

quality of life as a primary outcome measure) is arguable surgery (p=0·06).68 Very early surgery, within 6 h of

because, in principle, a patient with a poor outcome (ie, symptom onset, has even been shown to result in lower

954 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009

Review

mortality rates (1 of 12; 8·3%),94 and complications such as hypothesis that patients with aphasia might have a poorer

postoperative hydrocephalus might be reduced with the outcome after hemicraniectomy because of a loss of

early timing of this procedure.95 The studies that indicated ability to communicate.99 However, the handicap caused

a benefit of early surgery, however, were only suggestive, by aphasia, which only infrequently seems to remain

and selection bias might have undermined the strength of complete even after malignant MCA infarction,70,73,77

the conclusions. By contrast, a meta-analysis published in might be no less disabling than the neuropsychological

2004 by Gupta and colleagues,79 which included all data deficits seen in patients with infarction of the

reported from patients up to that date, did not confirm non-dominant hemisphere (eg, severe attention deficits

that delayed surgical decompression resulted in an and depression).81,82,96,100,101 Taking the meta-analyses and

increased case fatality rate and poorer outcome. prospective trials into account, mortality, functional

The pooled analysis from 2007 also did not adequately outcome, or quality of life do not seem to depend on

answer the question of whether surgery should be done which hemisphere is affected.5,11–13,79 Nonetheless, a

within 24 h or later as there was no difference in outcome definite conclusion is premature until more suitable data

among both groups (treated <24 h or >24 h), as measured are available.92 In summary, there is no indication at

on mRS scores; however, all included patients were present that patients with dominant malignant infarctions

treated within 48 h.13 Only the recently published do not benefit from surgery.

HAMLET trial allowed delayed surgery up to 96 h after

symptom onset.5 In secondary outcome analyses, results Quality of life and depression after surgery

from HAMLET revealed that surgical decompression Overall, both quality of life and depression seem to be

done within 48 h reduced the probability of having a poor similar after surgery and conservative treatment.71,72,81

outcome (defined as an mRS score of ≥5), whereas Although the retrospective agreement to decompressive

delayed hemicraniectomy after 48 h did not affect surgery was high in the trials done so far, the decision

outcome. However, only 11 of the 64 patients received about whether to operate on patients with a malignant

delayed surgery, so no final conclusions on possible MCA infarction should be made on an individual basis

benefits of hemicraniectomy beyond the 48-h time at present. Quality of life is the most important outcome

window can be made as yet.5,92 Nevertheless, on the basis variable; however, its assessment is hindered as

of the available data from the randomised trials, and in questionnaires are often completed by close relatives or

the absence of trials that truly compare early versus by patients who can be influenced by the perception of

delayed intervention, early decompression seems to be their relatives regarding their clinical status.72 The

beneficial.5,11,12 prospective trials and pooled analyses did not provide

conclusive results on quality of life and extent of

Age limit of surgery depression in patients who survived because of

All the randomised trials of hemicraniectomy have surgery,5,11–13 and the benefit of a decrease in mortality

enrolled only patients younger than 60 years of age. As from hemicraniectomy might be outweighed by a high

about 40% of patients with malignant MCA infarction number of severely disabled survivors.91 Because of the

are older than 60 years,4,26,78 whether these patients might findings of reduced mortality after surgery, there will be

also benefit from surgery remains unclear.92 Observational a reluctance to undertake trials that randomise patients

data indicate reduced case fatality but poor outcome with to receive conservative treatment for malignant MCA

functional dependency if patients older than 60 years infarction in the future; therefore, a control group

receive decompressive surgery,26,78,86,87,96,97 and the would not be available for questions on quality of life to

meta-analysis of 2004 indicated that age was the main resolve this important matter. Only a few patients in the

factor to affect outcome.79 The pooled analysis of 2007 did trials done so far survived malignant MCA infarction

not reveal differences in outcome (mRS 0–4 vs 5 or 6) after conservative treatment (24 of 65 patients in the

between patients younger and older than 50 years.13 The pooled analysis13), and further analyses on quality of

HAMLET trial, however, indicated that patients with an life, including long-term evaluation of patients included

age of 51–60 years were more likely to benefit from in these randomised trials, will be necessary.

surgery than were younger patients.5 On the basis of the

available data, a conclusion regarding an age limit for Conclusions

hemicraniectomy cannot be made. The planned Malignant MCA infarction was associated with high

DESTINY-II trial98 will study patients older than 60 years mortality for many years. The three European prospective

of age and will hopefully provide more information to randomised trials and the pooled analyses have revealed

answer this controversial question. a substantial increase in survival with decompressive

surgery. However, there are several clinical and ethical

Treatment of dominant versus non-dominant hemisphere questions that need to be resolved in future studies.

infarction These questions regard the timing of surgery (before or

The controversy of whether to treat or not treat patients after the 48-h time window), particularly as oedema

with dominant MCA infarction emerged from the formation often peaks after this time; the definition of a

www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009 955

Review

11 Vahedi K, Vicaut E, Mateo J, et al. Sequential-Design, Multicenter,

Search strategy and selection criteria Randomized, Controlled Trial of Early Decompressive Craniectomy

in Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction (DECIMAL trial).

References for this Review were identified through searches Stroke 2007; 38: 2506–17.

of PubMed with the search terms “hemicraniectomy”, 12 Jüttler E, Schwab S, Schmiedek P, et al. Decompressive Surgery

for the Treatment of Malignant Infarction of the Middle Cerebral

“malignant MCA infarction”, and “decompressive surgery” Artery (DESTINY): a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2007;

from 1970 until July, 2009. References selected were limited 38: 2518–25.

to core clinical journals. Articles were also identified through 13 Vahedi K, Hofmeijer J, Juettler E, et al. Early decompressive surgery

in malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery: a pooled

searches of the authors’ own files. Only papers published in analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol 2007;

English or German were reviewed. 6: 215–22.

14 Mitchell P, Gregson BA, Crossman J, et al. Reassessment of the

HAMLET study. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 602–03.

potential cut-off age, after which the effect of comorbidities 15 Heinsius T, Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G. Large infarcts in the

middle cerebral artery territory. Etiology and outcome patterns.

might undermine the positive effects of surgery; the Neurology 1998; 50: 341–50.

possible benefits of surgery on dominant versus 16 Ng LK, Nimmannitya J. Massive cerebral infarction with severe

non-dominant malignant MCA infarction; and the brain swelling: a clinicopathological study. Stroke 1970; 1: 158–63.

17 Balzer B, Stober T, Huber G, Schimrigk K. Space-occupying

analysis of long-term benefits on quality of life and cerebral infarct. Nervenarzt 1987; 58: 689–91 [in German].

depression in survivors after surgery versus those who 18 Bounds JV, Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Okazaki H. Mechanisms

receive conservative treatment.92 Resolving these and timing of deaths from cerebral infarction. Stroke 1981;

12: 474–77.

questions should be a main goal for future international

19 Jaramillo A, Gongora-Rivera F, Labreuche J, Hauw JJ, Amarenco P.

prospective studies in the field of stroke management. Predictors for malignant middle cerebral artery infarctions: a

Contributors postmortem analysis. Neurology 2006; 66: 815–20.

HBH and SS both undertook the literature search, wrote the paper, and 20 Brozici M, van der Zwan A, Hillen B. Anatomy and functionality of

approved the final version. leptomeningeal anastomoses: a review. Stroke 2003; 34: 2750–62.

21 Krieger DW, Demchuk AM, Kasner SE, Jauss M, Hantson L. Early

Conflicts of interest clinical and radiological predictors of fatal brain swelling in

We have no conflicts of interest. ischemic stroke. Stroke 1999; 30: 287–92.

Acknowledgments 22 Ropper AH. Lateral displacement of the brain and level of

We thank Alfred Aschoff (Department of Neurosurgery, University of consciousness in patients with an acute hemispheral mass.

N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 953–58.

Heidelberg, Germany), Gerald Suttner (Department of Psychiatry,

University of Erlangen, Germany), and the Department of 23 Berrouschot J, Sterker M, Bettin S, Koster J, Schneider D. Mortality of

space-occupying (‘malignant’) middle cerebral artery infarction under

Neuroradiology, University of Erlangen, Germany, for providing images

conservative intensive care. Intensive Care Med 1998; 24: 620–23.

and graphical assistance. We thank Martin Köhrmann (Department of

24 Wijdicks EF, Diringer MN. Middle cerebral artery territory

Neurology, University of Erlangen, Germany) and Eric Jüttler

infarction and early brain swelling: progression and effect of age

(Department of Neurology, Charité, University of Berlin, Germany) for on outcome. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73: 829–36.

constructive criticism on the contents of the paper. Finally, we thank

25 Kasner SE, Demchuk AM, Berrouschot J, et al. Predictors of fatal

Inken Martin (Molecular Cardiology, Victor Chang Cardiac Research brain edema in massive hemispheric ischemic stroke. Stroke 2001;

Institute, Australia) for language editing of the Review. 32: 2117–23.

References 26 Uhl E, Kreth FW, Elias B, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors

1 Hofmeijer J, Algra A, Kappelle LJ, van der Worp HB. Predictors of of hemicraniectomy for space occupying cerebral infarction.

life-threatening brain edema in middle cerebral artery infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75: 270–74.

Cerebrovasc Dis 2008; 25: 176–84. 27 Bosche B, Dohmen C, Graf R, et al. Extracellular concentrations of

2 Huttner HB, Jüttler E, Schwab S. Hemicraniectomy for middle non-transmitter amino acids in peri-infarct tissue of patients

cerebral artery infarction. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2008; 8: 526–33. predict malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 2003;

3 Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM. Stroke. Lancet 2008; 34: 2908–13.

371: 1612–23. 28 Dohmen C, Bosche B, Graf R, et al. Identification and clinical

4 Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, Spranger M, De Georgia M, impact of impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation in patients with

von Kummer R. ‘Malignant’ middle cerebral artery territory malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 2007; 38: 56–61.

infarction: clinical course and prognostic signs. Arch Neurol 1996; 29 Serena J, Blanco M, Castellanos M, et al. The prediction of

53: 309–15. malignant cerebral infarction by molecular brain barrier disruption

5 Hofmeijer J, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, Amelink GJ, van Gijn J, markers. Stroke 2005; 36: 1921–26.

van der Worp HB. Surgical decompression for space-occupying 30 Dohmen C, Sakowitz OW, Fabricius M, et al. Spreading

cerebral infarction (the Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral depolarizations occur in human ischemic stroke with high

Artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET]): a incidence. Ann Neurol 2008; 63: 720–28.

multicentre, open, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 326–33. 31 Dirnagl U. Cerebral ischemia: the microcirculation as trigger

6 Ropper AH, Shafran B. Brain edema after stroke. Clinical syndrome and target. Prog Brain Res 1993; 96: 49–65.

and intracranial pressure. Arch Neurol 1984; 41: 26–29. 32 Hamann GF. Acute cerebral infarct: physiopathology and modern

7 Frank JI. Large hemispheric infarction, deterioration, and therapeutic concepts. Radiologe 1997; 37: 843–52 [in German].

intracranial pressure. Neurology 1995; 45: 1286–90. 33 Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, et al. Computed tomographic

8 Hofmeijer J, van der Worp HB, Kappelle LJ. Treatment of parameters predicting fatal outcome in large middle cerebral artery

space-occupying cerebral infarction. Crit Care Med 2003; infarction. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003; 16: 230–35.

31: 617–25. 34 Lee SJ, Lee KH, Na DG, et al. Multiphasic helical computed

9 Bardutzky J, Schwab S. Antiedema therapy in ischemic stroke. tomography predicts subsequent development of severe brain

Stroke 2007; 38: 3084–94. edema in acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol 2004; 61: 505–09.

10 Jüttler E, Schellinger PD, Aschoff A, Zweckberger K, Unterberg A, 35 Dittrich R, Kloska SP, Fischer T, et al. Accuracy of perfusion-CT

Hacke W. Clinical review: therapy for refractory intracranial in predicting malignant middle cerebral artery brain infarction.

hypertension in ischaemic stroke. Crit Care 2007; 11: 231. J Neurol 2008; 255: 896–902.

956 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009

Review

36 Oppenheim C, Samson Y, Manai R, et al. Prediction of malignant 60 Diedler J, Sykora M, Blatow M, Jüttler E, Unterberg A, Hacke W.

middle cerebral artery infarction by diffusion-weighted imaging. Decompressive surgery for severe brain edema. J Intensive Care Med

Stroke 2000; 31: 2175–81. 2009; 24: 168–78.

37 Thomalla GJ, Kucinski T, Schoder V, et al. Prediction of malignant 61 Gruber A, Dorfer C, Knosp E. Mediainfarkt und kraniektomie.

middle cerebral artery infarction by early perfusion- and Derzeitige studienlage, operationsindikationen und organisatorische

diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke 2003; aspekte. J Neurol Neurochir Psychiatr 2008; 9: 12–19 [in German].

34: 1892–99. 62 Keller E, Wietasch G, Ringleb P, et al. Bedside monitoring of

38 Dohmen C, Bosche B, Graf R, et al. Prediction of malignant course in cerebral blood flow in patients with acute hemispheric stroke.

MCA infarction by PET and microdialysis. Stroke 2003; 34: 2152–58. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 511–16.

39 Lampl Y, Sadeh M, Lorberboym M. Prospective evaluation of 63 Jaeger M, Soehle M, Meixensberger J. Improvement of brain tissue

malignant middle cerebral artery infarction with blood-brain barrier oxygen and intracranial pressure during and after surgical

imaging using Tc-99m DTPA SPECT. Brain Res 2006; 1113: 194–99. decompression for diffuse brain oedema and space occupying

40 Bang OY, Saver JL, Alger JR, et al. Patterns and predictors of infarction. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2005; 95: 117–18.

blood-brain barrier permeability derangements in acute ischemic 64 Engelhorn T, Doerfler A, Kastrup A, et al. Decompressive

stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 454–61. craniectomy, reperfusion, or a combination for early treatment of

41 Berrouschot J, Rossler A, Koster J, Schneider D. Mechanical acute “malignant” cerebral hemispheric stroke in rats? Potential

ventilation in patients with hemispheric ischemic stroke. mechanisms studied by MRI. Stroke 1999; 30: 1456–63.

Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 2956–61. 65 Doerfler A, Forsting M, Reith W, et al. Decompressive craniectomy

42 Schwab S, Spranger M, Schwarz S, Hacke W. Barbiturate coma in in a rat model of “malignant” cerebral hemispheric stroke:

severe hemispheric stroke: useful or obsolete? Neurology 1997; experimental support for an aggressive therapeutic approach.

48: 1608–13. J Neurosurg 1996; 85: 853–59.

43 Steiner T, Ringleb P, Hacke W. Treatment options for large 66 Forsting M, Reith W, Schabitz WR, et al. Decompressive

hemispheric stroke. Neurology 2001; 57: S61–68. craniectomy for cerebral infarction. An experimental study in rats.

44 Schwab S, Aschoff A, Spranger M, Albert F, Hacke W. The value of Stroke 1995; 26: 259–64.

intracranial pressure monitoring in acute hemispheric stroke. 67 Doerfler A, Schwab S, Hoffmann TT, Engelhorn T, Forsting M.

Neurology 1996; 47: 393–98. Combination of decompressive craniectomy and mild hypothermia

45 Reith J, Jorgensen HS, Pedersen PM, et al. Body temperature in ameliorates infarction volume after permanent focal ischemia in

acute stroke: relation to stroke severity, infarct size, mortality, and rats. Stroke 2001; 32: 2675–81.

outcome. Lancet 1996; 347: 422–25. 68 Schwab S, Steiner T, Aschoff A, et al. Early hemicraniectomy in

46 Schwab S. Therapy of severe ischemic stroke: breaking the patients with complete middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke

conventional thinking. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 20 (suppl 2): 169–78. 1998; 29: 1888–93.

47 Bernard SA, Buist M. Induced hypothermia in critical care 69 Skoglund TS, Eriksson-Ritzen C, Sorbo A, Jensen C, Rydenhag B.

medicine: a review. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 2041–51. Health status and life satisfaction after decompressive craniectomy

for malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Acta Neurol Scand

48 Georgiadis D, Schwarz S, Aschoff A, Schwab S. Hemicraniectomy

2008; 117: 305–10.

and moderate hypothermia in patients with severe ischemic stroke.

Stroke 2002; 33: 1584–88. 70 Woertgen C, Erban P, Rothoerl RD, Bein T, Horn M, Brawanski A.

Quality of life after decompressive craniectomy in patients suffering

49 Georgiadis D, Schwarz S, Kollmar R, Schwab S. Endovascular

from supratentorial brain ischemia. Acta Neurochir 2004; 146: 691–95.

cooling for moderate hypothermia in patients with acute stroke:

first results of a novel approach. Stroke 2001; 32: 2550–53. 71 Vahedi K, Benoist L, Kurtz A, et al. Quality of life after

decompressive craniectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery

50 Kollmar R, Schabitz WR, Heiland S, et al. Neuroprotective effect of

infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76: 1181–82.

delayed moderate hypothermia after focal cerebral ischemia: an

MRI study. Stroke 2002; 33: 1899–04. 72 Benejam B, Sahuquillo J, Poca MA, et al. Quality of life and

neurobehavioral changes in survivors of malignant middle cerebral

51 Steiner T, Friede T, Aschoff A, Schellinger PD, Schwab S, Hacke W.

artery infarction. J Neurol 2009; 256: 1126–33.

Effect and feasibility of controlled rewarming after moderate

hypothermia in stroke patients with malignant infarction of the 73 Rieke K, Schwab S, Krieger D, et al. Decompressive surgery in

middle cerebral artery. Stroke 2001; 32: 2833–35. space-occupying hemispheric infarction: results of an open,

prospective trial. Crit Care Med 1995; 23: 1576–87.

52 Schwab S, Schwarz S, Spranger M, Keller E, Bertram M, Hacke W.

Moderate hypothermia in the treatment of patients with severe 74 Mori K, Aoki A, Yamamoto T, Horinaka N, Maeda M. Aggressive

middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 1998; 29: 2461–66. decompressive surgery in patients with massive hemispheric

embolic cerebral infarction associated with severe brain swelling.

53 Schwab S, Georgiadis D, Berrouschot J, Schellinger PD,

Acta Neurochir 2001; 143: 483–91.

Graffagnino C, Mayer SA. Feasibility and safety of moderate

hypothermia after massive hemispheric infarction. Stroke 2001; 75 Mori K, Nakao Y, Yamamoto T, Maeda M. Early external

32: 2033–35. decompressive craniectomy with duroplasty improves functional

recovery in patients with massive hemispheric embolic infarction:

54 Yager JY, Asselin J. Effect of mild hypothermia on cerebral energy

timing and indication of decompressive surgery for malignant

metabolism during the evolution of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage

cerebral infarction. Surg Neurol 2004; 62: 420–29.

in the immature rat. Stroke 1996; 27: 919–25.

76 Malm J, Bergenheim AT, Enblad P, et al. The Swedish malignant

55 Park J, Kim E, Kim GJ, Hur YK, Guthikonda M. External

middle cerebral artery infarction study: long-term results from

decompressive craniectomy including resection of temporal muscle

a prospective study of hemicraniectomy combined with standardized

and fascia in malignant hemispheric infarction. J Neurosurg 2009;

neurointensive care. Acta Neurol Scand 2006; 113: 25–30.

110: 101–05.

77 Kastrau F, Wolter M, Huber W, Block F. Recovery from aphasia

56 Robertson SC, Lennarson P, Hasan DM, Traynelis VC. Clinical

after hemicraniectomy for infarction of the speech-dominant

course and surgical management of massive cerebral infarction.

hemisphere. Stroke 2005; 36: 825–29.

Neurosurgery 2004; 55: 55–61.

78 Holtkamp M, Buchheim K, Unterberg A, et al. Hemicraniectomy in

57 Carandang RA, Krieger DW. Decompressive hemicraniectomy and

elderly patients with space occupying media infarction: improved

durotomy for malignant middle cerebral artery infarction.

survival but poor functional outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

Neurocrit Care 2008; 8: 286–89.

2001; 70: 226–28.

58 Wagner S, Schnippering H, Aschoff A, Koziol JA, Schwab S,

79 Gupta R, Connolly ES, Mayer S, Elkind MS. Hemicraniectomy for

Steiner T. Suboptimum hemicraniectomy as a cause of additional

massive middle cerebral artery territory infarction: a systematic

cerebral lesions in patients with malignant infarction of the middle

review. Stroke 2004; 35: 539–43.

cerebral artery. J Neurosurg 2001; 94: 693–96.

80 Foerch C, Lang JM, Krause J, et al. Functional impairment,

59 Wirtz CR, Steiner T, Aschoff A, et al. Hemicraniectomy with dural

disability, and quality of life outcome after decompressive

augmentation in medically uncontrollable hemispheric infarction.

hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarction.

Neurosurg Focus 1997; 2: E3.

J Neurosurg 2004; 101: 248–54.

www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009 957

Review

81 de Haan RJ, Limburg M, Van der Meulen JH, Jacobs HM, 92 Schneck MJ. Hemicraniectomy for hemispheric infarction and the

Aaronson NK. Quality of life after stroke. Impact of stroke type and HAMLET study: a sequel is needed. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 303–04.

lesion location. Stroke 1995; 26: 402–08. 93 Berger C, Kiening K, Schwab S. Neurochemical monitoring of

82 Walz B, Zimmermann C, Bottger S, Haberl RL. Prognosis of therapeutic effects in large human MCA infarction. Neurocrit Care

patients after hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery 2008; 9: 352–56.

infarction. J Neurol 2002; 249: 1183–90. 94 Cho DY, Chen TC, Lee HC. Ultra-early decompressive craniectomy

83 Els T, Oehm E, Voigt S, Klisch J, Hetzel A, Kassubek J. Safety and for malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Surg Neurol 2003;

therapeutical benefit of hemicraniectomy combined with mild 60: 227–32.

hypothermia in comparison with hemicraniectomy alone in 95 Waziri A, Fusco D, Mayer SA, McKhann GM 2nd, Connolly ES Jr.

patients with malignant ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006; Postoperative hydrocephalus in patients undergoing decompressive

21: 79–85. hemicraniectomy for ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Neurosurgery

84 Pillai A, Menon SK, Kumar S, Rajeev K, Kumar A, Panikar D. 2007; 61: 489–93.

Decompressive hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral 96 Leonhardt G, Wilhelm H, Doerfler A, et al. Clinical outcome and

artery infarction: an analysis of long-term outcome and factors in neuropsychological deficits after right decompressive

patient selection. J Neurosurg 2007; 106: 59–65. hemicraniectomy in MCA infarction. J Neurol 2002; 249: 1433–40.

85 Wang KW, Chang WN, Ho JT, et al. Factors predictive of fatality 97 Yao Y, Liu W, Yang X, Hu W, Li G. Is decompressive craniectomy for

in massive middle cerebral artery territory infarction and clinical malignant middle cerebral artery territory infarction of any benefit

experience of decompressive hemicraniectomy. Eur J Neurol 2006; for elderly patients? Surg Neurol 2005; 64: 165–69.

13: 765–71. 98 Current Controlled Trials. Decompressive surgery for the treatment

86 Maramattom BV, Bahn MM, Wijdicks EF. Which patient fares of malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery 2. http://www.

worse after early deterioration due to swelling from hemispheric controlled-trials.com/mrct/trial/617395/destiny (accessed Aug 17,

stroke? Neurology 2004; 63: 2142–45. 2009).

87 Rabinstein AA, Mueller-Kronast N, Maramattom BV, et al. Factors 99 Delashaw JB, Broaddus WC, Kassell NF, et al. Treatment of right

predicting prognosis after decompressive hemicraniectomy for hemispheric cerebral infarction by hemicraniectomy. Stroke 1990;

hemispheric infarction. Neurology 2006; 67: 891–93. 21: 874–81.

88 Curry WT Jr, Sethi MK, Ogilvy CS, Carter BS. Factors associated 100 Erban P, Woertgen C, Luerding R, Bogdahn U, Schlachetzki F,

with outcome after hemicraniectomy for large middle cerebral Horn M. Long-term outcome after hemicraniectomy for space

artery territory infarction. Neurosurgery 2005; 56: 681–92. occupying right hemispheric MCA infarction. Clin Neurol Neurosurg

89 Stroke Trials Register. HeMMI: Hemicraniectomy For Malignant 2006; 108: 384–87.

Middle Cerebral Artery Infarcts. http://www.strokecenter.org/trials/ 101 Goto A, Okuda S, Ito S, et al. Locomotion outcome in hemiplegic

trialDetail.aspx?tid=575&search_string=hemmi (accessed Aug 17, patients with middle cerebral artery infarction: the difference

2009). between right- and left-sided lesions. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;

90 Bousser MG. Some translations in vascular neurology. The 18: 60–67.

Johann Jacob Wepfer Award 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008; 26: 328–34.

91 Puetz V, Campos CR, Eliasziw M, Hill MD, Demchuk AM.

Assessing the benefits of hemicraniectomy: what is a favourable

outcome? Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 580.

958 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 8 October 2009

You might also like

- Acute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyFrom EverandAcute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyEdgar A. SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- SNH CraniotomyDocument8 pagesSNH CraniotomyxshreNo ratings yet

- Vach Ha 2015Document26 pagesVach Ha 2015HumbertoHurtadoNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument53 pagesJournal ReadingRhadezahara PatrisaNo ratings yet

- Moya MoyaDocument7 pagesMoya MoyaJoandre FauzaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Mechanical Thrombectomy TechniquesDocument8 pagesOverview of Mechanical Thrombectomy Techniquesjaknews adminNo ratings yet

- Protocols: Destiny Ii: Decompressive Surgery For The Treatment of Malignant Infarction of The Middle Cerebral Artery IiDocument8 pagesProtocols: Destiny Ii: Decompressive Surgery For The Treatment of Malignant Infarction of The Middle Cerebral Artery Iirodolfo riosNo ratings yet

- Guia MoyamoyaDocument7 pagesGuia MoyamoyaAndresPinedaMNo ratings yet

- [19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery] Hemodynamic analysis of the recipient parasylvian cortical arteries for predicting postoperative hyperperfusion during STA-MCA bypass in adult patients with moyamoya disease (1)Document8 pages[19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery] Hemodynamic analysis of the recipient parasylvian cortical arteries for predicting postoperative hyperperfusion during STA-MCA bypass in adult patients with moyamoya disease (1)AlejitaplafuenteNo ratings yet

- Bateman2017Document6 pagesBateman2017Meris JugadorNo ratings yet

- Endovascular Management of Acute Epidural Hematomas: Clinical Experience With 80 CasesDocument7 pagesEndovascular Management of Acute Epidural Hematomas: Clinical Experience With 80 CasesDeby AnditaNo ratings yet

- HSA e Isquemia Tardia 2016Document12 pagesHSA e Isquemia Tardia 2016Ellys Macías PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Highlights October-2023-Stroke-HighlightsDocument1 pageHighlights October-2023-Stroke-HighlightsAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Descompressive CraniectomyDocument13 pagesDescompressive CraniectomyBryan Santiago ApoloNo ratings yet

- Mks 054Document7 pagesMks 054Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Resumption of Antithrombotic Agents in C PDFDocument28 pagesResumption of Antithrombotic Agents in C PDFNurul FajriNo ratings yet

- Presentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergDocument13 pagesPresentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergAlexandra CNo ratings yet

- Letters: Safety of Angioplasty For Intracranial Artery ReferencesDocument5 pagesLetters: Safety of Angioplasty For Intracranial Artery Referencesaula nisafitriNo ratings yet

- A Case Report On Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysm.44Document5 pagesA Case Report On Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysm.44SuNil AdhiKariNo ratings yet

- 2022 The Intensive Care Management of Acute Ischaemic StrokeDocument9 pages2022 The Intensive Care Management of Acute Ischaemic StrokeOmar Alejandro Agudelo ZuluagaNo ratings yet

- Treating The Acute Stroke Patient As An EmergencyDocument9 pagesTreating The Acute Stroke Patient As An EmergencyAnonymous EAPbx6No ratings yet

- 30947630Document12 pages30947630carolinapolotorresNo ratings yet

- Strokeaha 107 485235Document12 pagesStrokeaha 107 485235rodolfo riosNo ratings yet

- Stroke Mimics VagalDocument12 pagesStroke Mimics VagalBrunaProençaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Subarachnoid HaemorrhageDocument11 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Subarachnoid Haemorrhagemedicinainterna.umaepNo ratings yet

- Hemorragia IntracerebralDocument9 pagesHemorragia IntracerebralEdwin Jofred Torres HuamaniNo ratings yet

- Decompressive Craniectomy For Acute Isquemic Stroke (09-16)Document8 pagesDecompressive Craniectomy For Acute Isquemic Stroke (09-16)Ailson Corrêa TolozaNo ratings yet

- Controversies in The Neurosurgical Management of Cerebellar Hemorrhage and InfarctionDocument10 pagesControversies in The Neurosurgical Management of Cerebellar Hemorrhage and InfarctionThiago SouzaNo ratings yet

- 4 - 01-03-07 - J Neurosurg 2007 - Decompressive Hemicraniectomy in Malignant MCA InfarctionDocument7 pages4 - 01-03-07 - J Neurosurg 2007 - Decompressive Hemicraniectomy in Malignant MCA InfarctionThiago Scharth MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Critical Care and Emergency Medicine Neurology in StrokeDocument3 pagesCritical Care and Emergency Medicine Neurology in StrokeAnca GuțuNo ratings yet

- Aneurysm BJADocument17 pagesAneurysm BJAParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- C 17 Hydrocephalus in Myelomeningocele: Shunts and Problems With ShuntsDocument10 pagesC 17 Hydrocephalus in Myelomeningocele: Shunts and Problems With ShuntsTeuku Arie HidayatNo ratings yet

- Evolving Concepts of The Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque and TheDocument16 pagesEvolving Concepts of The Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque and TheKhánh Nguyễn NgọcNo ratings yet

- Thick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument9 pagesThick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageVanessa LandaNo ratings yet

- Scientific Report Journal 22 NovDocument6 pagesScientific Report Journal 22 Novnaresh kotraNo ratings yet

- Imagingofacutestroke: Current StateDocument9 pagesImagingofacutestroke: Current Statealejandro echeverriNo ratings yet

- Journal NeuroDocument6 pagesJournal NeuroBetari DhiraNo ratings yet

- ICA'sDocument37 pagesICA'sVeronica TanNo ratings yet

- Stroke 4Document12 pagesStroke 4David JuanNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Review On Craniectomy And.28Document4 pagesContemporary Review On Craniectomy And.28ja.arenas904pfizerNo ratings yet

- Rutman Et Al 2022 Incidental Vascular Findings On Brain Magnetic Resonance AngiographyDocument13 pagesRutman Et Al 2022 Incidental Vascular Findings On Brain Magnetic Resonance AngiographySofía ValdésNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous ThrombosisDocument14 pagesCerebral Venous ThrombosisSrinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Brain HemorrhagesDocument9 pagesBrain HemorrhagesAyashopia AyaNo ratings yet

- The EXCEL and NOBLE Trials - Similarities, Contrasts and Future Perspectives For Left Main RevascularisationDocument8 pagesThe EXCEL and NOBLE Trials - Similarities, Contrasts and Future Perspectives For Left Main RevascularisationRui FonteNo ratings yet

- Thrombolytic Therapy For Ischemic StrokeDocument7 pagesThrombolytic Therapy For Ischemic StrokechandradwtrNo ratings yet

- Cryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesCryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticenellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Oncologic Emergencies in The Head and NeckDocument20 pagesOncologic Emergencies in The Head and NeckEduardo FrancoNo ratings yet

- Eco Doppler Trascraneal 5Document15 pagesEco Doppler Trascraneal 5David Sebastian Boada PeñaNo ratings yet

- Predictors and Outcomes of Shunt-Dependent Hydrocephalus in Patients With Aneurysmal Sub-Arachnoid HemorrhageDocument8 pagesPredictors and Outcomes of Shunt-Dependent Hydrocephalus in Patients With Aneurysmal Sub-Arachnoid HemorrhageNovia AyuNo ratings yet

- Cir 0000000000000985Document20 pagesCir 0000000000000985abraham rumayaraNo ratings yet

- Acute Coronary Syndromes Without ST-Segment Elevation - What Is The Role of Early Intervention?Document3 pagesAcute Coronary Syndromes Without ST-Segment Elevation - What Is The Role of Early Intervention?Rui FonteNo ratings yet

- Noninvasive Coronary Angiography: Hype or New Paradigm?Document3 pagesNoninvasive Coronary Angiography: Hype or New Paradigm?odiseu81No ratings yet

- Bruce C V Campbell Ischaemic Stroke 2019Document22 pagesBruce C V Campbell Ischaemic Stroke 2019yiyecNo ratings yet

- Personal ViewDocument12 pagesPersonal ViewanankastikNo ratings yet

- The Role of Imaging in Acute Ischemic Stroke: E T, M.D., Q H, M.D., P .D., J B. F, M.D., M W, M.D., M.a.SDocument17 pagesThe Role of Imaging in Acute Ischemic Stroke: E T, M.D., Q H, M.D., P .D., J B. F, M.D., M W, M.D., M.a.Schrist_cruzerNo ratings yet

- Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants Do Not Increase Cerebral MicrobleedsDocument5 pagesNon-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants Do Not Increase Cerebral MicrobleedsAniNo ratings yet

- Emergency Management of Intracerebral HemorrhageDocument7 pagesEmergency Management of Intracerebral HemorrhageHey AndyNo ratings yet

- 7 Cavernomas LawtonDocument374 pages7 Cavernomas LawtonJohnny GorecíaNo ratings yet

- Ehv 217Document8 pagesEhv 217Said Qadaru ANo ratings yet

- PolipillDocument10 pagesPolipillSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Utility of PET ComputedDocument10 pagesUtility of PET Computedkevin ortegaNo ratings yet

- J Jacc 2022 08 737Document13 pagesJ Jacc 2022 08 737kevin ortegaNo ratings yet

- Hepatology - 2022 - Fontana - AASLD Practice Guidance On Drug Herbal and Dietary Supplement Induced Liver Injury 1Document29 pagesHepatology - 2022 - Fontana - AASLD Practice Guidance On Drug Herbal and Dietary Supplement Induced Liver Injury 1kevin ortegaNo ratings yet

- Biomarkers in Heart FailureDocument6 pagesBiomarkers in Heart Failurekevin ortegaNo ratings yet

- Autoinmune Hepatitis GuidelinesDocument52 pagesAutoinmune Hepatitis Guidelineskevin ortegaNo ratings yet

- ISPD Peritonitis Guideline Recommendations: 2022 Update On Prevention and TreatmentDocument44 pagesISPD Peritonitis Guideline Recommendations: 2022 Update On Prevention and TreatmentMisael JimenezNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Asthma: Common Signs and Symptoms of Asthma IncludeDocument18 pagesRespiratory Asthma: Common Signs and Symptoms of Asthma IncludeAen Panda BebeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kad Dan HonkDocument9 pagesJurnal Kad Dan Honksimpati91No ratings yet

- Multicystic Encephalomalacia: An Autopsy Report of 4 CasesDocument7 pagesMulticystic Encephalomalacia: An Autopsy Report of 4 CasesadiNo ratings yet

- Surgery For Cerebral Contusions: Rationale and Practice: Review ArticleDocument4 pagesSurgery For Cerebral Contusions: Rationale and Practice: Review ArticleIshan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Common Postmortem Computed Tomography Findings Following Atraumatic Death - Differentiation Between Normal Postmortem Changes and Pathologic LesionsDocument12 pagesCommon Postmortem Computed Tomography Findings Following Atraumatic Death - Differentiation Between Normal Postmortem Changes and Pathologic LesionsFrédérique ThicotNo ratings yet

- ENLSV3.0 ICP FinalDocument7 pagesENLSV3.0 ICP FinalGustavo HenrikeNo ratings yet

- MeningitisDocument27 pagesMeningitisVinay SahuNo ratings yet

- Clinical Efficacy of Mannitol (10%) With Glycerine (10%) Versus Mannitol (20%) in Cerebral OedemaDocument6 pagesClinical Efficacy of Mannitol (10%) With Glycerine (10%) Versus Mannitol (20%) in Cerebral OedemaLailNo ratings yet

- Traduccion Neurointensivismo Fluidoterapia en Paciente NeurocriticoDocument12 pagesTraduccion Neurointensivismo Fluidoterapia en Paciente NeurocriticoAlanNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney Injury at The Neurocritical CareDocument10 pagesAcute Kidney Injury at The Neurocritical CareSamNo ratings yet

- CSF Shift Edema PublishedDocument15 pagesCSF Shift Edema PublishedIype CherianNo ratings yet

- Neuroanesthesiology UpdateDocument23 pagesNeuroanesthesiology UpdateAhida VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Edema: BBB (Blood Brain Barrier)Document4 pagesCerebral Edema: BBB (Blood Brain Barrier)Mohamed Al-zichrawyNo ratings yet

- Pharm Care in Stroke-1Document45 pagesPharm Care in Stroke-1Achmad Triwidodo AmoeNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Brain InjuryDocument39 pagesTraumatic Brain InjuryDung Nguyễn Thị MỹNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Brain TumorsDocument15 pagesPathophysiology of Brain TumorsTRASH MAILNo ratings yet

- Berhanu .E (M.D) : 08/02/20 1 Bacterial Meningitis For C-I StudentDocument41 pagesBerhanu .E (M.D) : 08/02/20 1 Bacterial Meningitis For C-I StudentRidwan kalib100% (1)

- September Issue 3 MCJ 36 Pages 2022Document36 pagesSeptember Issue 3 MCJ 36 Pages 2022Sathvika BNo ratings yet

- Transient Ischemic Attack Precipitating Factors Predisposing FactorsDocument6 pagesTransient Ischemic Attack Precipitating Factors Predisposing FactorsYosef OxinioNo ratings yet

- Early Complementary Acupuncture Improves The CliniDocument8 pagesEarly Complementary Acupuncture Improves The ClinikhalisahnNo ratings yet

- Cerebellar StrokeDocument12 pagesCerebellar StrokewhitecloudsNo ratings yet

- MSN Lesson Plan 3Document15 pagesMSN Lesson Plan 3spalte48No ratings yet

- Neuropathology PDFDocument205 pagesNeuropathology PDFNarendraNo ratings yet

- Intracranial Pressure (ICP) : Causes, Concerns and ManagementDocument37 pagesIntracranial Pressure (ICP) : Causes, Concerns and ManagementGus LionsNo ratings yet

- Head InjuryDocument69 pagesHead Injuryheena solankiNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis in ChildrenDocument6 pagesDiabetic Ketoacidosis in ChildrenviharadewiNo ratings yet

- Pub - Principles and Practice of NeuropathologyDocument608 pagesPub - Principles and Practice of NeuropathologyArkham AsylumNo ratings yet

- Berkowitzs Pediatrics A Primary Care Approach 6nbsped 9781610023726 9781610023733 9781610024105 2019938969 1610023722 - CompressDocument1,244 pagesBerkowitzs Pediatrics A Primary Care Approach 6nbsped 9781610023726 9781610023733 9781610024105 2019938969 1610023722 - CompresshassanNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Treatment of SevereDocument13 pagesPathophysiology and Treatment of SevereIva Pinasti DestaraniNo ratings yet

- Alterations in Pediatric Neurological Function: Lisa Musso, ARNP, MN, CPNP Seattle UniversityDocument66 pagesAlterations in Pediatric Neurological Function: Lisa Musso, ARNP, MN, CPNP Seattle Universityfadumo65No ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)