Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Life in The DMZ

Life in The DMZ

Uploaded by

Nóra KissOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Life in The DMZ

Life in The DMZ

Uploaded by

Nóra KissCopyright:

Available Formats

Life in the DMZ: Turning a Diplomatic Failure into an Environmental Success

Author(s): LISA M. BRADY

Source: Diplomatic History , SEPTEMBER 2008, Vol. 32, No. 4, SPECIAL FORUM WITH

ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY (SEPTEMBER 2008), pp. 585-611

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24916002

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24916002?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Diplomatic History

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LISA M. BRADY

Life in the DMZ: Turning a Dipl

an Environmental Success

On 28 July 1953, representatives from several nations met at the tiny Korean

farming village of Panmunjom and inadvertently created one of Asia's most

important nature sanctuaries. Establishing a wildlife preserve was never a goal of

the armistice that ended the Korean War, of course, but it nevertheless is a

significant consequence of those diplomatic negotiations. A wide variety of

Korea's native plants and animals, as well as numerous migratory species, were

the direct beneficiaries. For some, like the red-crowned or Manchurian crane,

the existence of the sanctuary has meant the difference between survival and

pvtinr-finn

The accidental nature preserve coincides with the

long demilitarized zone (DMZ), which was set up as

hostilities and to establish neutral ground where Nor

work toward eventual reunification. Internal divisions within the two Koreas

and continued distrust between them, combined with the Cold War agendas of

the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, and the United States,

ensured that the temporary divide took on a more permanent character. For

decades, the DMZ has symbolized diplomatic failure, but from an environmen

tal perspective, it is one of the Cold War's greatest successes.

The DMZ is a cross-section of the peninsula's geography. Approximately 40

miles north of Seoul, its western terminus bisects the estuarine delta created by

the confluence of the Han and Imjin rivers as they empty into the Yellow Sea.

From there it stretches through Korea s western and central lowlands (where

farming had been the major economic activity before the war) until it climbs

rolling foothills into the rugged, densely forested Taebaek-san Mountains,

which run along the eastern edge of the peninsula and slope precipitously to the

East Sea (Sea of Japan). Although narrow, the DMZ represents a nearly com

plete set of Korean ecosystems within its boundaries, ranging from wetlands to

grasslands to mountainous highlands, all of them largely untouched by human

i. A note on names: the spelling for Korean place names reflects that commonly found in

English-language documents. For individuals, I follow the Korean convention of placing the

surname first, excepting those whose published work lists their names according to Western

conventions and prominent figures, like Syngman Rhee, whose name order is typically reversed

in English-language sources.

Diplomatic History, Vol. 32, No. 4 (September 2008). © 2008 The Society for Historians of

American Foreign Relations (SHAFR). Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street,

Maiden, MA, 02148, USA and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK.

5»5

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

586 DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

activities since the end of the war. Altho

DMZ had been managed and cultivated fo

since that conflict's end nature has flour

mines still in the area). A new ecological

war and maintained by diplomacy. In an i

diplomatic failure brought peace to a smal

for the peninsula's nonhuman residents.

Migratory birds in particular have ben

Smithsonian alerted its readers that the t

ing the extinction of some of Asia's mos

David R. Zimmerman, pointed to the

agreement and gave a brief, three-sente

"had been heavily settled and farmed. Th

was left alone." This last stage of the DM

man that if given a chance, "nature he

pointed to the work ot Dr. Ceorge Archi

since 1974 had been studying the white-n

the DMZ as safe feeding and resting gro

Archibald, too, the reversion of the D

nature heals itself."3 Its recovery could

intervention continued to be minimal in the area. Zimmerman warned that the

preserve "could quickly be ruined if a peace treaty were to end the need for a

buffer," but he hoped for the development of what he called "ornithological

diplomacy," where international cooperation to ensure the survival of the cranes

would trump any ideological or geopolitical agendas.4

Fifteen years after the Smithscmian article, Peter Matthiessen traveled to the

DMZ to cover the cranes' story for Audubon. Matthiessen, like Zimmerman,

noted the accidental nature of the wildlife preserve, but his interviews with Dr.

Archibald—still studying the cranes—were tinged with sadness. South Korea had

only just begun its major push to industrialize when Zimmerman wrote his article

in 1981; by the time Matthiessen visited, the nation had undergone a develop

mental and economic "miracle." It was also beginning to witness the environ

mental problems such as pollution and erosion that came with such rapid and

far-reaching change. In just a decade and a half, increased industrial and agricul

tural development across the nation had taken its toll on the crane populations, all

but eliminating them in the civilian control zone (CCZ), a 3-20 mile wide area

abutting the South Korean side of the DMZ.5 Matthiessen was encouraged,

however, that 85 percent of South Koreans polled by the Korea Environmental

2. David R. Zimmerman, "A Fragile Victory for Beauty on an Old Asian Battleground,"

Smithsonian 12 (October 1981): 57.

3. Ibid., 60.

4. Ibid., 63.

5. Peter Matthiessen, "Accidental Sanctuary," Audubon 98 (July-August 1996): 54.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

T tu* nA\7 . r«n

Technology Research Institute saw the environm

economic development."6 Despite the setbacks in

sen ended on a hopeful note, reiterating Archibald

respectful it would be to those who had to die her

proiecieu as naruingers or peace ana morning canii. '

The DMZ and CCZ contain much of Korea's remaining biodiversi

reserves because most of the peninsula has been urbanized or developed

industrial or agricultural purposes. The DMZ has not undergone compre

sive ecological analysis for obvious reasons, but satellite data, scientific stu

the CCZ, and anecdotal evidence provide a basic catalog of the species that

claimed the territory since the end of the war. According to the research,

are over 1200 plant species, 83 fish varieties, 51 different mammals (represen

over half of the peninsula's total fauna types), and numerous birds, insect

microorganisms. Many of these species are listed as threatened or endang

and some were even thought to be extinct.8 Some of the more optim

accounts of the area's wildlife populations point not just to the cranes but

the possibility of the return of the Amur, or Siberian, tiger after a mor

fifty-year absence.9

The biodiversity in the DMZ and surrounding areas presents a un

opportunity not just for scientists and conservationists but for diplomats as

Interviewed for Technology Review about the DMZ, Arthur Westing, ecol

and former director of the United Nations Environment Programme's P

Security, and Environment Project, suggested that for the two Koreas,

ronmental issues may be the least provocative way of breaking the ice."1

means of facilitating that diplomatic thaw, Dr. Ke Chung Kim, a profes

of entomology and the director of Pennsylvania State University's C

for Biodiversity Research, proposed in 1994 the creation of a Korean Pe

Bioreserves System that would include the DMZ and a 3 mile buffer zon

either side, totaling 1600 square miles." Although Kim is only one of many

6. Ibid., 106.

7. Ibid., 107. Korea is known as the "Land of the Morning Calm."

8. Ke Chung Kim, "Preserving Biodiversity in Korea's Demilitarized Zone," Science 278

(10 October 1997): 242-43. See also Kwi-Gon Kim and Dong-Gil Cho, "Status and Ecological

Resource Value of the Republic of Korea's De-Militarized Zone," Landscape and Ecological

Engineering 1 (2005): 3-15. Kim and Cho's study examined the areas in the DMZ and CCZ

adjacent to the two railroads that now connect the two countries. Although the study was

limited, the results are still suggestive.

9. Norimitsu Onishi, "Does a Tiger Lurk in the Middle of a Fearful Sanctuary?," New York

Times (late ed., East Coast), 5 September 2004, sec. 1, p. 14. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/

09/o5/international/asia/o5dmz.html.

10. Joy Drohan, "Sustainably Developing the DMZ," Technology Review 99, no. 6 (August

September 1996): 17. For more on the DMZ issue, see "Maintaining No Man's Land,"

Environment 39 (December 1997): 24; Tom O'Neill, "Korea's Dangerous Divide: DMZ,"

National Geographic 204, no. 1 (July 2003): 2-26; and "Korean DMZ's Environmental

Treasures Need Protection," International CustomWire, 13 January 2004.

11. Ke Chung Kim, "Preserving Biodiversity in Korea's Demilitarized Zone," 242-43.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

588 DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

have researched and studied the biodiversity

to propose making the area into a permanen

Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) an

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) have sup

Kim that such a park "has the potential not

region but also to ease the hostility between

ing mutually sustainable development of the

In the late 1990s, Kim's hopes captured

publications ranging from Science and Envir

and the New York Times.'4 Many of these s

preserving the DMZ's ecology as critical to a

tions between the two Koreas, while at the sa

terrible state of the peninsula's natural env

partly a pursuit of modernization, partly a g

led to vast deforestation, habitat loss, declin

cant air and soil pollution across the penins

as a symbol both for Korea's past and its fut

Regrettably, the topic has received very lit

press, and even there most discussions of th

continuing tensions. Military histories of

examine the diplomatic, strategic, and operat

of the DMZ.15 General histories of Korea jus

12. The Korean-born Kim has done a great deal to h

only by proposing the Korean Peace Bioreserves Sy

founding the international organization the DMZ

preserve the DMZ. Ted Turner, the American media

"Ted Turner: Turn Korean DMZ into Peace Park,"

from http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/200

November 2005). Turner was a keynote speaker at a c

August 2005, where he delivered an address titled

Development for Peace in Korea." Information on an

found at the DMZ Forum website, http://www.dmzf

13. Drohan, "Sustainably Developing the DMZ."

14. The following list is representative but not

Developing the DMZ"; "Maintaining No Man's L

Civilization 3 (October-November 1996): 44-45; Mi

Korea's DMZ Conceals a Haven for Animals," Wall Str

Ai; Josie Glausiusz, "Healer of a Divided Land: In

21 (November 2000): 30; Lucille Craft, "Breaking D

Peace, on the Korean Peninsula?" Japan Times, 17

www.japantimes.c0.jp/cgi-bin/fv20020917al.html (

Kim and Edward O. Wilson, "The Land that War Pr

December 2002; and Nick Easen, "Korea's DMZ: T

able from http://edition.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/as

23 February 2005).

15. Despite its being known as the "forgotten war,

secondary) examining the military history of the Ko

Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2 vols. (Pri

The Limited War (New York, 1964); Matthew B. Ridg

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the nation's cultural, social, and political development.'6 Nature often gets only

glancing attention in these studies, despite its fundamental importance in

shaping Korean history. In light of the ecological developments in the DMZ,

nature can no longer be ignored. One source that does address this issue, if only

briefly, is journalist Don Oberdorfer's 1997 book The Two Koreas: A Contempo

rary History. His first chapter, "Where the Wild Birds Sing," opens with an

image of white-naped cranes peacefully floating above a verdant landscape

riotous with wildflowers and inhabited by hundreds of other species. The DMZ,

in Oberdorfer's words, is "a richly forested, unspoiled ... strip of land that

stretches like a ribbon .. . across the waist of the Korean peninsula." He further

noted that the resident species generally remain unmolested by human inter

lopers because of "a densely planted underground garden of deadly land mines,

which the birds and animals somehow use a sixth-sense to avoid."'7

Whether or not nonhuman species can detect land mines instinctively is

debatable, but Oberdorfer clearly demonstrated both that the DMZ is impor

tant ecologically and that its future as a safe habitat for Korea's wildlife is far

from secure. "The serenity [in the DMZ] is deceptive," he warned. "All sides are

heavily armed and ready at a moment's notice to fight another bloody and

devastating war. Now that the Berlin wall has fallen and the Soviet Union has

collapsed, this pristine nature preserve marks the most dangerous and heavily

fortified border in the world," one that has been "violated by tunnels, defiled by

infiltrators, and scarred by armed skirmishes." Even the "melodic call of its

birds" cannot compete with the "harsh propaganda" spewing from the loud

speakers both sides have erected to antagonize or seduce their enemies across

the ideological and geographical divide.'8

The repercussions of two competing economic and ideological systems have

left Korea's environment at risk, and the DMZ is no exception. According to a

2003 CNN report, "While poverty alleviation would likely prevent North

Korea from putting much weight on nature conservation in the DMZ, for its

southern neighbor it would be the prospect of further economic development

and integration with the North that would be a driving force for development."'9

There is reason to hope, however, both for a unified Korea and for the contin

ued existence of the nature preserve, even if those two goals seem contradictory

on the surface. The end of the Cold War and occasional thaws in diplomatic

Challenge (Garden City, NY, 1967); William Stueck, The Korean War: An International History

(Princeton, NJ, 1995); William Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and

Strategic History (Princeton, NJ, 2002); and U.S. Department of the Army, United States Army

in the Korean War, 4 vols. (Washington, DC, 1961-1972).

16. Three very useful sources on Korean history generally are Bruce Cumings, Korea's Place

in the Sun: A Modern History (New York, 1997); Don Oberdorfer, The Two Koreas: A Contem

porary History (1997; rev. and updated ed., New York, 2001); and Roger Tennant, A History of

Korea (London, 1996).

17. Oberdorfer, Two Koreas, 1.

18. Ibid., 2.

19. Easen, "Korea's DMZ: The Thin Green Line."

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

590 : DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

relations between North and South Korea finally have brou

tive into the realm of the possible, although realization of it

away. A growing interest in maintaining the DMZ as a natu

and international environmental organizations and by the e

may prevent the large-scale development that would surely f

Korea's political past and its environmental future are ine

What follows is an analysis of the diplomatic and economic d

Korean Peninsula during the latter half of the twentieth centur

of environmental history. Integrating diplomatic and envir

methods reveals not just a fuller view of the implications of

played out in Korea but also provides a reminder that the lin

choices and environmental changes must not be ignored. Far

the relationship is unidirectional, this study also shows that

historical force in its own right and that its ability to thrive de

has shaped cultural and political decisions with significant

tions. 1 his essay, then, is an exploratory study that uses some ot the most

important scholarship on economic and political trends in both Koreas during the

Cold War as a foundation for new insights into the diplomatic and environmental

implications of establishing the DMZ as an international peace park.

background: wwii, the Korean war, and the creation

OF TWO KOREAS

Once a united land, the Korean Peninsula no longer r

Su-Kang-San," or land of embroidered rivers and moun

source of national pride.20 The geography of the Korean

by the eastern spine of mountains formed by the nor

southern Taebaek-san ranges and their foothills, which

quarters of the land area of the peninsula. Its rich biod

muse for Korean poets and artists for centuries, and its m

tiger, plays an important role in Korea's founding myth

the peninsula's natural wealth, along with its strategic l

a target of expansionistic powers.

Geography, according to Oberdorfer, "dealt Korea a p

role." The peninsula is situated in "a strategic but dang

that made it vulnerable to invasion (more than nine hun

two thousand years) and subject to occupation by powers

Mongols, Japan, the United States, and the Soviet Unio

20. Ke Chung Kim, "Preserving Biodiversity in Korea's Demi

21. For a translation of the Korean nation's origin story, see Cu

Sun, 23-24. See also "Dan-Gun, First King of Korea," in Folk Tales

trans. Zong In-Sob (Elizabeth, NJ, 1982), 3-4. Tigers are the subjec

legends and stories included in Zong's collection.

22. Oberdorfer, Two Koreas, 4.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 591

was largely tolerated, even at times welcomed, Japan's was vehemently opposed.

The enmity between Korea and Japan has a long history, dating back to the

Japanese invasion of the peninsula in the sixteenth century. Japan's industrial

ization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and its subsequent

search for resources led to its aggressive expansionism. Although other nations

had interests in exploiting Korea's resources (including gold, coal, and timber),

Japan's claims gained priority after its victory in the Russo-Japanese War in

1905.23 Just five years later, Japan officially declared Korea a possession and

began a thirty-five-year occupation. Thus, outside interests—not internal

attempts at industrialization or modernization—initiated a decades-long period

of natural resource exploitation and environmental degradation that signaled a

dramatic change from Korea's traditional relationship with the natural world.

Historically, Korea was an agricultural nation. Much of its cultivable land lies

in the south and west, although a narrow fringe along the coastal areas in the

north does provide additional cropland. The region's bimodal climate, with

win, ui y vv iiiLwi j a il va iiva l, vvv^l a lu i iinv^i o, pu3L3 u.Aia\^Liv_ ^naiiv^JLigv_o lui dgii^uiLUit,

which Koreans early on adapted to and managed through terracing, irrigatio

schemes, and village-based farming. A feudal system of land tenure, headed by

the yangban (landlords), emerged at least as early as the fourteenth century.

Under Japanese occupation in the early twentieth century, this social system

changed little as the yangban integrated into the colonial bureaucracy/4 The

political changes led to changes in Korean agricultural practices, however

Tenant farmers increasingly lost political and economic power under th

Japanese occupation and, as their increased taxes and rents caused them t

default on loans, many chose the even harsher life of slash-and-burn agricultur

in the mountains, which some have argued was the origin of Korea's significan

deforestation problem.25

23. This deal was negotiated by President Theodore Roosevelt and is considered by some

to be the first betrayal of Korea by the United States. Roosevelt essentially exchanged Japanes

recognition of American rights in the Philippines for American acceptance of Japan's claims i

Korea. Oberdorfer, Two Koreas, 5. See also Cumings, Korea's Place in the Sun, 141-42.

24. For a description of early farming practices, see Tennant, History of Korea, 2. For a

description of Korean social strata, see Cumings, Korea's Place in the Sun, 51-53. Peasants wer

usually either tenant farmers or slaves. The term yangban is applied to the landed gentry of the

Choson Dynasty (1392-1910) and also to a class of scholar-officials. See Tennant, History o

Korea, 135-57, and John Lie, Han Unbound: The Political Economy of South Korea (Stanford, CA,

1998), 5-18, passim. Cumings uses the latter definition, Korea's Place in the Sun, 141.

25. Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, vol. 1, Liberation and the Emergence o

Separate Regimes, 1945-1947 (Princeton, NJ, 1981), 39-45. As of 2005, 66 percent of the natio

was forested, but colonization, the Korean War, and postwar efforts of reconstruction create

a situation in which "these forests had been badly devastated from reckless logging for

firewood, reclamation, and slash-and-burn farming methods." Cheong Wa Dae (Office o

the President), "Natural Environment: Forests and Farmlands," 2; http://english

president.go.kr/cwd/en/korea/Korea_03_5_c.htm!?m_def=5&ss_def=3 (last accessed 18

November 2005). After the Korean presidential election in 2007, the Office of the President

web site changed and no longer contains this page. Printed copies of this page, and others cite

herein, are in author's collection.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

592 : DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

In addition to expanding and commercializing Korea's agr

Japanese also initiated industrialization there by establishin

industry throughout the peninsula. Furthermore, the Japan

extensive railroads linking Korea with ports and markets as

and Paris, connecting the peninsula with "new forms of exc

Japan but with the world market system."26 In addition to rail

built extensive highways and expanded Korean seaports, an

had a much better-developed transport and communications

any other East Asian country save Japan."27 Thus, in a very sh

Korea was transformed from a feudalistic agrarian society

agrarian society with the bare bones of an industrial econom

Cumings has suggested that "it was the simultaneity of the co

and the rise of industry that was so critical to shaping the fate

Japanese and thereafter. This was, in essence, the onset of

revolution."28 The effects of these transformations would

aiung uic peimibuia, ab uie oeuunu vvuiiu war liiterveiieu ana traiibrornieu

Korea in unimaginable ways.

The rapidity of development and the circumstance under which it

left Korea and its people in a vulnerable position at the end of Wor

Although this situation is not unique to Korea—other nations suffe

conditions as decolonization and Cold War antagonisms reshaped

litical scene—Korea was one of only two nations physically rent

postwar wrangling for power, and of the two, the only one to

colonized before the war.29 That colonization "was intense and bitter

to Cumings, and it "shaped postwar Korea deeply." Cumings ex

brought development and underdevelopment, agrarian growth and

tenancy, industrialization and extraordinary dislocation, political m

and deactivation; it spawned a new role for the central state, new sets

political leaders, communism and nationalism, armed resistance and t

collaboration; above all, it left deep fissures and conflicts that have gn

Korean soul ever since."30 Koreans faced these issues as a single, if

nation until 15 August 1945, when the Allies hastily divided the peni

northern and southern zones at the 38th parallel.31

20. Cumings, Korea's Place in the Sun, 166.

27. Ibid., 167.

28. Cumings, Origins of the Korean War, 1: 48.

29. Germany was the other nation, of course, that was divided in two. Vietnam could also

fall into this category, but its division was much shorter in duration.

30. Cumings's chapter on the colonial period is excellent, and provides much more detailed

analysis of the political and economic ramifications of Japanese occupation. See "Eclipse,

1905-1945," in Korea's Place in the Sun, 139-84. Quotation from p. 148.

31. For a description of the decision process, see Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War, 11-12,

and Cumings, Korea's Place i?i the Sun, 187. Consideration of the issue began on 10 August 1945,

immediately following Japan's first intimations that it would consider surrender. General

George Lincoln chose the 38th parallel, Colonels Charles Bonesteel and Dean Rusk confirmed

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 593

The 38th parallel was initially intended "to be a purely military demarcation

of a temporary nature to facilitate the surrender [of] the Japanese forces in

Korea."32 Although the ultimate decision on where to split Korea took only a

matter of minutes, the diplomatic discussions and negotiations regarding the

nation's postwar fate had been going on for several years. On 1 December 1943,

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek issued the

Cairo Declaration, which stated, "The Three Great Allies are fighting this war

to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for them

selves and have no thought of territorial expansion." Japan was to be stripped of

all the territory it had "taken by violence and greed" and, "mindful of the

enslavement of the people of Korea," the three Allied powers were "determined

that in due course Korea shall become free and independent."33 Although the

Cairo Declaration did not provide for the division of the Korean peninsula, the

clause "in due course" did allow for a period of further administration by foreign

powers.

nri _

i iiv^ vl umuii vv ao nut ui^iuu^u jlii vjj.ai-u.iii: uiv^ v>anvj auuii

because it had not yet enter

on 8 August 1945, however

ing Korea's fate. The Mosco

roles for all four allies and

development as a precurs

USSR Joint Commission th

regions on either side of

Americans in the southern

United States, Great Britain

This trusteeship would adv

its suitability, and the proposal

his General Order no. I, which o

38th parallel was unfortunate for

In 1904, hoping to avoid a mili

Peninsula, Japan proposed carv

parallel. Russia refused, the Russ

Korea. Rusk later noted that if h

a different line of demarcation.

32. Soon Sung Cho, "American

Korean Relations, 1882-1982, IF

1982), 66.

33. "The Cairo Declaration," in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations,

The United States and the Korean Problem: Documents, 1943-1953 (Washington, DC, 1953)

(hereafter Documents), 1.

34. "U.S.S.R. Declaration of War against Japan," in Documents, 1. General Douglas Mac

Arthur's General Order no. 1, issued in Yokohama, Japan on 7 September 1945, was the initial

document determining the governance of postwar Korea, but outlined only the U.S. authority

on the peninsula. General Order no. 1 stated: "All powers of Government over the territory

of Korea south of 38° north latitude and the people thereof will be for the present exercised

under my [MacArthur's] authority." See "Establishment of Boundary at the 38th Parallel," in

Documents, 2-3.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

594 : diplomatic history

for up to five years, after which Koreans would elect

independent government.35

Almost immediately after the Joint Commission wa

and the Americans began pushing their own Cold W

opposing political factions within Korea. The Americ

tions of the Western-educated and fiercely anti-Com

The Soviets backed the former guerilla commander K

had consolidated his political power, Rhee in the sou

and Kim in the North. Each claimed to head the legi

entire peninsula. Both the Soviets and the Americans

Korea later that year, believing that their respective a

establishing a single, unified government for the pe

Rhee nor Kim would compromise. With the permissi

Mao Zedong, Kim initiated military operations on

intention of unifying the peninsula under his Commu

Thp krnrpan Wfctr was nnK/ the first mainr hattlecrrrmnrl in the mnrh larorer

Cold War between communism and democratic capitalism.37 Despite its inter

national character and importance, the Cold War took on localized meanings for

Koreans, North and South, and had a devastating physical impact on the pen

insula. The hot war in Korea wrought incredible physical damage. Fighting

ranged across the entire peninsula and, along the 38th parallel in particular, the

35- "The Moscow Agreement," in Documents, 4. China's role in the administration of

postwar Korea changed dramatically, of course, with the Communist victory in that nation's

civil war in 1949. After that point, China allied itself with the Soviet Union, and the Cold War

tensions in the region were increased significantly.

36. Scholars have debated the origins of the war. Bruce Cumings has argued that it was

initially a civil war, and only later became part of the larger Cold War once the Chinese, Soviets,

and Americans deployed troops to the peninsula in support of their respective Korean allies.

See Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, vol. 1. Cumings reinforced this argument in his

general history of Korea, Korea's Place in the Sun, 238 ff. Others, like William Stueck and Don

Oberdorfer, have suggested that the war had both internal and external origins, neither o

which can be separated from the other. According to Stueck, the war "cannot be understood

without heavy reference to nations and forces beyond the peninsula." Certainly, the fighting

was initially between Koreans, and the war "contained an important civil dimension," but its

origins "can only be explained through the interaction of Korean and non-Korean elements and

through decisions made in Moscow, Beijing, and Washington, as well as in Pyongyang and

Seoul." Stueck further argued that although the Koreans on both sides of the 38th parallel were

"intensely" nationalist, "their fate was so closely tied to the designs of the United States, the

Soviet Union, and China that their ability to act independently was severely circumscribed."

Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War, 66. See also Oberdorfer, Two Koreas, 8-11. Allan Millett

bridges these two approaches, suggesting that partisan conflict beginning in 1948 was the actual

start to the war, but that these internal conflicts were shaped by international agendas. See Allan

Millett, The War for Korea, 1945-1950: A House Burning (Lawrence, KS, 2003).

37. I characterize the Cold War here as a conflict between political and economic systems

generally, recognizing that there are vast differences among the nations involved. Often, the

democratic capitalist states (the United States and Great Britain in particular) supported

anti-Communist totalitarian regimes which were neither democratic nor capitalist themselves,

but were nonetheless considered part of the "Free World." For a concise history of the Cold

War, see John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A History (New York, 2005).

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 595

battles were long and protracted. Widespread destruction of cities, farms, and

forests left many areas on the peninsula devastated. American air campaigns

incorporated firebombing with napalm and targeted and destroyed North

Korean irrigation dams that supplied the nation with water for three quarters of

its agricultural production.'8 The massive amounts of ordnance used in bombing

campaigns left visible scars on the landscape that were still obvious decades after

the armistice was signed.39 Whereas these changes to the landscape were imme

diate and devastating, the armistice, division, and resulting ideological antago

nism would result in more long-term, and ultimately more destructive,

environmental consequences.

nruce turnings noteu 111 ms uook lyurw J\urea: nnuirjtr t^uunrry mar me

Korean War was "a war between two conflicting social and economic systems."4"

The intense ideological competition was not limited to military confrontation

and political posturing, but played out in both sides' push for economic devel

opment. After the war, the demilitarized zone at the 38th parallel provided a

neat boundary along which both sides could compare their progress. In 1972,

Johan Galtung, then part of the International Peace Research Institute in Oslo,

suggested that both Koreas "helped create a Korea in their image . . . making

ample use of the 1945 division as well as of past Korean history. If both pairs

believed the other pair to be fundamentally aggressive, why should they not

make the most out of 'their' Korea as a buffer zone to protect themselves?"4'

Both nations' ambitions necessarily depended on expanded exploitation of their

natural resources, which led to severe environmental degradation on both sides

of the DMZ.

foreground: postwar development as a factor of cold

WAR POLICIES

Development after the 1950-1953 Korean War took on

sophical importance as well as economic purpose for both

rapid industrialization and astonishing agricultural pro

similar endeavors in South Korea until the 1970s. The lac

38. Bruce Cumings, North Korea: Another Country (New Yor

suggests that the use of napalm in Korea exceeded that in Vietnam

it had greater destructive effect, particularly because of the larg

population of North Korea than North Vietnam (ibid., 16).

39. During a visit to Kaesong in 1987, historian Bruce Cumin

through the streets of Kaesong in the early morning hours and fi

could gaze upon Mount Song-ak in its fullness: and there on its

pockmarks, still easily visible, made by the pounding of southern a

which sits along the 38th parallel just nortb of the DMZ, was the c

(918-1392), from which the Westernized name for the nation is deriv

237.

40. Cumings, North Korea, 6.

41. Johan Galtung, "Divided Nations as a Process: One State, *Iw

The Case of Korea," Journal of Peace Research 9, no. 4 (1972): 347.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

596 DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

in the southern half of the peninsula in th

to support Kim II Sung's claims about

Communist Utopia.42 North Korea's earl

hensive political consolidation under Kim

through nationalization of industry and

strategies, and "moral incentive policies."

to encourage workers and frequent exho

ceaselessly and selflessly for nonmaterial

Mass production campaigns such as "Ca

Day Speed Batde" urged industrial and ag

and output for the good of the state.4S

pretation of Marxist-Leninist philosophy

unique history as a subjected nation.

Kim's fiercely nationalistic juche id

reliance") urged North Koreans to wor

intervention, nut reality neiied tne ideal. Uespite iNortn Korea s more recent

history of intense isolationism, the nation's early industrial progress was only

made possible by help from its Communist allies. U.S. bombing during

the 1950-1953 war destroyed the heavy industry that had been established

previously in the area under Japanese occupation. Almost immediately after the

armistice was signed, Soviet bloc countries in a show of Communist solidarity

helped Kim rebuild those facilities.

Industrial might was the key to independence according to the. juche philoso

phy and agricultural output was emphasized only as it supported North Korea's

industrial development. Indeed, similar to Mao's Great Leap Forward, Kim II

Sung's Chollima Work Team Movement, instituted in the late 1950s, "was

designed to mobilize human and material resources in agriculture for the pri

ority development of heavy industry." The Chollima Movement had broader

implications as well, in that its primary goal "was to combine the programs of

ideological indoctrination and agricultural reform . . . based on a general-line

42. John Lie suggests that the primary reason Kim succeeded in gaining popular support

for his policies in the North (apart from being a revolutionary hero who fought vigorously

against the Japanese occupation) was his immediate implementation of land reform. This was

an extremely important issue because Korean peasants had been under the thumbs of the

yangban landlords for centuries. Conversely, the South Korean government, heavily influenced

by the United States, initially opposed any kind of land reform, making for a difficult transition.

See John Lie, Han Unbound, 9.

43. Byoung-Lo Philo Kim, Two Koreas in Development: A Comparative Study of Principles and

Strategies of Capitalist and Communist Third World Development (New Brunswick, NJ and

London, 1992), 2. Kim notes that such development is effective only in the short term, when

it "can be achieved by expanded utilization of natural resources and unemployed labor," and

tends to fall behind in the long term because "productivity must be raised through more

advanced technology" and because such rapid changes tend to exhaust motivation (ibid., 3).

44. Ibid., 148. Other incentives were "mass movements, moral exhortations, and political

campaigns" (ibid.).

45. Ibid., 127.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 597

policy with moralistic fervor and ideological appeal to increase maximum pro

ductivity."46 North Korea's focus on heavy industry was not just a factor of

ideology, however. It also reflected its available natural resources. Where the

North is poor in arable land, it is rich in minerals, controlling 90 percent of the

peninsula's lead deposits and 98 percent of its bituminous coal.47 Initially, North

Korea's development went unimpeded, and for twenty-five years after the DMZ

firmly separated the two Koreas, the North enjoyed far greater economic

success than the South.48 Its success, however, was fragile, literally and ideologi

cally, and began to founder once the initial benefits of such things as chemical

fertilizers, pesticides, and industrialization took their toll on the soil and water

of the nation.49

Given the restrictive nature of North Korea's contact with the world, histo

rians face great difficulty in assessing the environmental consequences of that

nation's development policies.50 Satellite images are one good indicator of the

nation's current problem with deforestation. Air, water, and soil pollution are

more difficult to document, as are problems with biodiversity and other envi

ronmental concerns. In 2003, UNEP published a report on North Korea,

providing a long-awaited remedy to this dearth of information. The report,

"State of the Environment: DPR Korea," as with all such UNEP reports, was

completed in conjunction with the host state. The statistical information and

a^iciiLiiic udid iidvc nui uccii cALciiidiiy vcjLiiicu üxiu Liic i cpui L may nuiicpicscni

an objective assessment of the possible negative ramifications of the Kim

ty's policies. However, it does point to some issues North Korea recogn

imperative to remedy.

The UNEP report focused on five general categories of concern for

Korea: forest depletion, water quality degradation, air pollution, land

dation, and diminished biodiversity. A thorough reading of each sectio

cates that the foundational problem North Korea faces, and the o

underlies all other problems, is deforestation. According to the

"Increase of population and the demand for food and firewood has exe

pressure on the forest ecosystem of the country resulting [in] loss of h

46. Ibid., 148. Byoung-Lo Philo Kim noted earlier in his book that the C

Movement was responsible for impressive industrial growth in the 1950s and 19

porting "41.7 and 36.6 percent during the Three-Year and Five-Year Plans, respe

(p. 121).

47. Ibid., 77. Significant resources for iron, steel, zinc, and copper production also support

North Korea's heavy industry, the majority of which is fueled by coal-fired power stations.

Ibid., 140.

48. Cumings points to published CIA data indicating that the South Korean economy only

caught up to the North Korean one in 1978. Cumings, North Korea, 185. This is also evident

in John Lie's assessment of the two nations' economic growth in the same period. See Lie, Han

Unbound. Both sources state that the South's real economic boom occurred in the 1980s, and at

that time overshot the North's capability to catch up.

49. Andrew Natsios, The Great North Korean Famine (Washington, DC, 2001), 13-14.

50. This has long been a problem for researchers. See Andrea Matles Savada, ed., North

Korea: A Country Study (Washington, DC, 1993), 55.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

598 DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

and frequent occurrence of natural disas

report contended that the nation has lon

the problem. "Even during the war," the

the entire people continued for reforesta

of the Military Commission." The policie

successfully, the report conceded, lar

industrial development."52

Likewise, water, air, land, and biodiversit

as well as to continuing development pla

section of the report: pollution, land degr

be attributed to a growing population,

fertilizers and pesticides, and large-scale e

on biodiversity, the report concluded, "B

protection and development in DPR Kore

the plan for biodiversity conservation in

111C11L. 1 iO I1U VV V_ V V^l a LUllU^llV.^ lu IgllUl^. [U1WJ ^»1

centrate heavily on development alone"53 (see Figures i and 2). F

report noted, "The conflict between socio-economic progress and a pat

sustainable development is likely to be further aggravated unless emer

can be settled in time." The report does not explain precisely w

"emerging issues" are, but urges "both bilateral and multilateral int

cooperation in the environmental field."S4

Despite identifying numerous problems with North Korea's enviro

status, the report errs on the side of caution in criticizing the nation

It pointed to several laws passed to address environmental issues, inclu

"Law on Environmental Protection," the "Land Law," and the "Fo

and to efforts by the government to educate the North Korean popul

environmental protection through such means as TV and radio

ments, artistic activities, and "Wild Animals Awareness Month."55 Th

of such programs is not clear, and in light of the juche philosophy

rigidity of policy resulting from the Kims' claims of infallibility, a

change under the continued Communist regime seems unlikely. Alth

difficult to prove that all the environmental changes that took plac

Korea had direct connections to the larger ideological conflict of

51. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), "State of the Environ

Korea, 2003" (Klong Luang, Thailand, 2003), 23. The report is available fro

www.rrcap.unep.org/reports/soe/dprksoe.cfm (accessed 10 January 2006).

52. Ibid., 23-24. The report points to this particular incident as the beginn

"reforestation policy": "Since the great leader Comrade Kim II Sung planted t

Moonsu Hill in Pyongyang City on 6 April 1947 in order to publicize the need for

throughout the country, many efforts have been undertaken for afforestation/refore

year in DPR Korea" (p. 23).

53. Ibid., 58.

54. Ibid., 65.

55. Ibid., 58.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 599

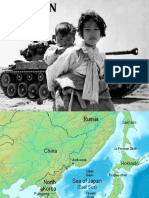

Figure i: Bridge of No Return looking toward North Korea. The lighter areas in the center

of the image are bare soil, vulnerable to erosion. If North Korea continues its intensive

exploitation of its natural resources, the land may never be able to recover. Making the DMZ

a permanent nature preserve might help to mitigate the environmental problems both Koreas

face. Photo by author.

•1

•"S1IB Hjl .. ■Jtx—'' ***

Figure 2: View of Kijong-dong, DPR Korea from a Panmunjom viewing area. Known as

"Peace Village" north of the DMZ and "Propaganda Village" south of it, Kijong-dong (or

Gijeong-dong) sits directly opposite Daeseong-dong in South Korea. Although the southern

village has been permanendy inhabited for many generations, Kijong-dong is home only to a

skeleton maintenance crew. Despite its lack of population, the scars of economic and ideologi

cal competition can be seen in the extensive clearing on the mountain behind the buildings.

Establishing the DMZ as a bioreserve may belie the South's cynical moniker and prove the

North's vision of the area to be prophetic. Photo by author.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6oO : DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

War, studies of other Communist nations' environmental

strong correlation.'6

It is clear, however, that the U.S.-backed government in

development as an imperative to stave off a Communist tak

John Lie, suggested, "The threat of North Korea—and beh

international communism—provided ample motivation for

offer vital military and economic support to South Korea."5

Eder noted in Poisoned Prosperity that "Koreans and Ameri

recognized that the South's security could not be maintaine

growth and modernization at all levels of life."'8 In addition

ests in Korea, that nation's development was also a mea

revitalization of Japan's devastated postwar economy. Cumin

World War II, Korea had "growing importance to America

part of a new, dual strategy of containing communism and r

industrial economy as a motor of the world economy."59 Ind

V^UiU VVdl UtllUU, JUUU1 1VU1 td StlVtU <111 1111UU1 IdllL lUlt 111 Lilt iTVllltl ILdll C*±

containment through political stability and economic growth.

The first of these objectives—political stability—was ne

second—economic growth—but it proved very difficult t

Korea's liberation from Japan in 1945 through the late 19

struggled with almost continuous political upheaval, despite h

presidents for its first thirty-two years of existence. Peasant

reform regularly revolted, student protestors demanded real

occasional assassinations and military coups thwarted U.S. hope

productive South Korea. Both the Syngman Rhee (1945-1961)

Hee (1961-1980) administrations enjoyed moments of calm, bu

dissent made economic development difficult to sustain.

One solution to these challenges was to address a long-stand

inequity—land distribution. In 1949, Rhee enacted a law t

holdings at 7.5 acres and provided compensation for dispo

56. Perhaps the best indication that Kim's Cold War-era developmen

blame is to look at its closest neighbor, geographically and ideologically:

of China. Judith Shapiro ably demonstrated the problems Mao's Commun

China's environment in Mao's War against Nature: Politics and the Environme

China (New York, 2001). The Soviet Union also had tremendous environ

described in Douglas R. Weiner, Models of Nature: Ecology, Conservation, and

in Soviet Russia (Pittsburgh, 2000), and Douglas R. Wiener, A Little Corner

Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev (Berkeley, CA and Los Angele

57. Lie, Han Unbound, 166. This becomes especially true when Ronal

president in 1980, the same year Park is assassinated and Chun Doo Wa

South Korea. "Instead of continuing Carter's stress on human right

single-minded anticommunist policy that tolerated repressive but friend

Unbound, 122.

58. Norman Eder, Poisoned Prosperity: Development, Modernization and

South Korea (Armonk, NY and London, 1996), 5.

59. Cumings, Korea's Place in the Sun, 209-10.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 601

?flko — JM . ».

mp ^**52*^

*ssa» »——•

»<iA

! *

US StSI

3?ISE BjsfAj auiffl B«ga|

~ ' -10D1.1002 J

Figure 3: A bag of "DMZ Rice." Grown by the farmers of Da

settlement allowed in the DMZ, the rice is both a staple for sur

souvenir for the thousands of tourists who visit the DMZ each

Implementation did not occur until 1952, howev

accidental—that year military stalemate set in and R

beleaguered regime—and it ultimately "contributed t

defeat."60 Land reform successfully curtailed any lo

ment and finally destroyed the centuries-oldyangban

changed agricultural practices in South Korea. The pe

were no longer responsible to landlords, whose status

landownership, but instead answered to the demands o

Lie argued resulted in the "commodification of agrar

This "irreversible and accelerated process" led to Ove

and "marked the end of an ecologically sustainab

redistribution, based partly on an ethic of social ref

toward combating Communist sympathies, was only

nomic development and subsequent environmental de

Substantial economic changes did not take hold in

the ouster of Rhee in 1961, however. Rhee's rabid

prevented him from fully integrating with Japan's g

step in Korean economic development. Under the

Hee, the 1965 normalization treaty with Japan brou

immediate infusion of capital into the Korean eco

brought a development strategy with serious environ

60. Lie, Han Unbound, 4-18; quotation from p. 11.

61. Ibid., 16.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6o2 : diplomatic history

nation adopted "the low-technology, labor-intensive

low value-added production that Japanese companies

Another development in the 1960s that served to i

only into the expanding Asian economy but the U.S.

Vietnam War. That conflict underlined Korea's strat

crucial catalyst for South Korea's economic and indu

Koreans not only provided troops to the military effo

important trading partner with the United States, pr

other light manufactures. By the 1970s, nearly three

exports were to either Japan or the United States.63

ization spurt in the 1960s and early 1970s was, thus, a

and externally derived Cold War policies. Taken as a

dramatic implications for the nation's people and its

Deforestation and pollution were two major conseq

push to develop. As in North Korea, the visible effe

South are clear on current satellite images of the pe

subsistence to commercialized agriculture after the

for deforestation, as more and more land was neede

cities and industrial centers. Erosion caused by defore

tion of the Park administration as early as 1962. Th

government instituted a nationwide retorestation and

Although the policy was largely successful in increasi

sacrificed biodiversity for economic growth by prom

economically viable conifer species.64 Economic deve

mental health.

Likewise, the "fundamental reason for the pollution

state's single-minded stress on economic growth," ac

compounding factor was the effect of industriali

concept of nature. The Cheong Wa Dae (South Korean

noted, "Although the vast majority remained in awe

forefront of national development began embracing t

ment is an object to be conquered and used to one's o

cut down, factories were built, and pesticides sprayed

disregard for their impact on the environment."66

62. Ibid., 60.

63. This summary of Korea's economic rise is adapted from Lie, "Muddling toward a

Take-Off," in Han Unbound, 43-74.

64. According to the official website of the Office of the President, the South Korean

government instituted a nationwide program on erosion control and reforestation in 1962.

Cheong Wa Dae (Office of the President), "Natural Environment: Forests and Farmlands," 2.

(Page no longer available; copy in author's collection. See note 25.)

65. Lie, Han Unbound, 162.

66. Cheong Wa Dae, "Environment: Overview," 1; http://english.president.go.kr/cwd/en/

korea/Korea_03_5.html?m_def=5&ss_def=3 (last accessed 18 November 2005). Page no longer

available; copy in author's collection (see note 25).

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 603

similarly argued that the development of a market-oriented society in South

Korea came with negative environmental impacts, largely because Koreans

did not associate environmental destruction with the market and economic

growth.67 Indeed, according to professor of urban planning Cho Myung-Rae,

"the environment was viewed ambivalently either as something people were

subordinate to or as something to be overcome or transformed in order to create

a better material life."68

The first official recognition of a problem with industrial pollution coincided

with Park's first Five Year Economic Development Plan in 1962. The South

Korean government passed a "Pollution Prevention Act" the following year, but

because of a lack of resources, it had little impact on diminishing the industrial

smoke that had become "a symbol of Korea's economic development."6' Four

vear«? later health nrnhlem<; and acrrirnltnral damacre hecran to emertre near I Than

the nation's first industrial complex. Monetary compensation for victims and

resettlement programs—not environmental cleanup—represented the govern

ment's answer to complaints and requests for assistance. Grassroots antipollution

and victims' rights organizations formed in response. According to sociologist

Yohei Harashima, however, "under the authoritarian political regime of the late

1960s, the government regarded antipollution movements as antigovernmen

tal."70 Such opposition to public protest created the conditions that led to the

outbreak between 1983 and 1986 of pollution-related diseases near Onsan,

another industrial complex.7' Little environmental progress was made until South

Korea began to democratize and "carried out massive structural reforms in social

and economic domains to join the ranks of advanced countries."72

67. Lee Hongkyun, "Environmental Awareness and Environmental Practice in Korea,"

Korea Journal 44, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 182.

68. Cho Myung-Rae, "Emergence and Evolution of Environmental Discourses in South

Korea," Korea Journal 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 143.

69. Yohei Harashima, "Effects of Economic Growth on Environmental Policies in

Northeast Asia," Environment 42 (July-August 2000): 32.

70. Ibid.

71. The so-called Onsan disease had similar symptoms to Minimata disease, which had

developed in Japan three decades earlier. Several articles discuss Onsan disease as a case study

or as a pivotal moment in the development of South Korean environmentalism. See Xuemei Bai

and Hidefumi Imura, "A Comparative Study of Urban Environment in East Asia: Stage Model

of Urban Environmental Evolution," International Review for Environmental Strategies 1, no. 1

(Summer 2000): 135-58; Moon Chung-in and Lim Sung-hack, "Weaving through Paradoxes:

Democratization, Globalization, and Environment Politics in South Korea," East Asian Review

15, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 43-70; Harashima, "Effects of Economic Growth on Environmental

Policies"; and Ku Do-Wan, "The Korean Environmental Movement: Green Politics through

Social Movement," Korea Journal 44, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 185-219. For a scientific analysis of

the disease, see Chul-Hwan Koh et al., "Analysis of Trace Organic Contaminants in Sediment,

Pore Water, and Water Samples from Onsan Bay, Korea: Instrumental Analysis and In Vitro

Gene Expression Assay," Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 21, no. 9 (2002): 1796-1803.

72. Cheong Wa Dae, "Environment: Overview," 1; http://english.president.go.kr/cwd/en/

korea/Korea_03_5.html?m_def=5&ss_def=3 (last accessed 18 November 2005). (Page no longer

available; copy in author's collection. See note 25.) On the relationship between democratization

and environmentalism in Korea, see Ku, "The Korean Environmental Movement."

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6oa DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

In the end, industrialization "brought a

tional environmental landscape" that c

modern environmental consciousness and discourse."73 Nature conservation

became part of the nation's policies in 1978, and air and water quality standards

were enacted that same year. In 1980 a clause in the Korean constitution

"guaranteed people the right to live in a clean, healthy environment."74 The

environmentalism that developed in South Korea was neither an intended nor

anticipated product of American policies in the region, but industrialization was,

just as it was a Soviet goal in the North.75

Likewise, the nature sanctuary that evolved in the DMZ could not have

been foreseen in 1953, when the line was "temporarily" drawn across the

peninsula. However, this unintended consequence may prove to be the basis

for the final end to the Cold War in Korea. In 1998, Ke Chung Kim founded

the DMZ Forum, an international, nonprofit organization committed to

transforming the DMZ from a symbol of war and continued strife "into a

World Peace Park for Humanity, Research, and Biodiversity." This idea is

based on the belief that the narrow strip of land offers the greatest potential

for Korean reconciliation and reunion.76 According to Kim and the DMZ

Forum, the DMZ represents "a laboratory for advancing scientific understand

ing of natural processes and for educating the world" and that species "in the

DMZ could successfully re-establish those that have been eliminated in both

North and South in the rush to improve living standards." Furthermore,

by "building a Peace Park together, the two Koreas can rebuild common

traditions and consider a common future. Scientific exploration, sustainable

development and eco-tourism could profitably replace costly and dangerous

military confrontation."77 Arthur Westing, a long-time scholar of war's effects

73- Cho, "Emergence and Evolution of Environmental Discourses in South Korea," 144.

Cho's article is one of several that Korea Journal included in its autumn issue (vol. 44, no. 3,

2004), which was in part dedicated to studies of the development of environmentalism in South

Korea. See Cho, "Emergence and Evolution of Environmental Discourses in South Korea,"

138-64; Lee, "Environmental Awareness and Environmental Practice in Korea," 165-84; Ku,

"The Korean Environmental Movement"; and Moon Tae Hoon, "Environmental Policy and

Green Government in Korea," 220-51. Ku Do-Wan generally agreed with the trajectory of

environmentalism in Korea described by Cho, but suggested that it can be better explained

through the process of democratization, rather than through simple deterioration of the natural

environment, as Cho suggested. Cheong Wa Dae agreed with this interpretation, noting that

in the 1980s the South Korean government initiated numerous laws protecting the environ

ment. See Cheong Wa Dae, "Environment: Overview," and Lie, Han Unbound, 163.

74. Harashima, "Effects of Economic Growth on Environmental Policies," 32.

75. Just as in the United States and Europe, the rise of an environmental movement in

South Korea was a direct response to local problems and the consequences of development.

Although environmentalists in South Korea were certainly aware of a growing environmental

ethos and movement elsewhere, it was not until the 1990s that many such organizations turned

from local, anti-pollution platforms to broader-based, "global" issues. See Ku, "The Korean

Environmental Movement." See also Moon and Lim, "Weaving through Paradoxes."

76. DMZ Forum, 2002 Newsletter; available from http://www.dmzforum.org/news_

events/2002_o6.php (accessed 30 March 2007).

77. Ibid.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 605

on the environment, agreed. Interviewed for a report in Technology Review,

Westing stated, "The environment is a benign, seemingly apolitical issue on

which the Koreans could possibly agree."78

new ground: the dmz as potential peace park

After decades of intermittent hostilities,

in the DMZ from 1966 to 1969, the ribbon

physical barrier and as a symbol of separati

potential for unity and peace.79 The great

coming the long-lasting effects of the Co

Korean Peninsula. As Bruce Cumings has s

divisions that we associate with the Cold War were the reasons for Korea's

division; they came early to Korea, before the onset of the global Cold War, and

today they outlast the end of the Cold War everywhere else."80 The DMZ is a

symbol of the "tragedy of war" and is "a sacred resting place for millions of

innocent [civilian] compatriots, foreign friends, and soldiers of both sides who

died for freedom and peace."81 It also has become a place that represents the

potential for "reconciliation and concordance" and that could serve "as a

gateway to unification and peace." The DMZ's "rich biodiversity and landscapes

opens a unique opportunity" for "sustainable development and peace" across the

npninsnla

Where the global ideological conflict ushered in dev

pollution, and death across much of the Land of th

vided a real calm in the DMZ that allowed life to prolif

DMZ cannot be overstated—without the devastation o

the division of the peninsula, important elements of

may well have been lost forever. Whereas the bro

to be fully analyzed by environmental historians, th

despite its negative impact on the natural world thro

78. Drohan, "Sustainably Developing the DMZ." For mo

"Maintaining No Man's Land"; O'Neill, "Korea's Dangerous

Environmental Treasures Need Protection," International Custom

79. For a brief history of the DMZ shadow war, see William R

Conflict," Military History 16 (October 1999): 38-44. There ha

armed engagements, large and small, along and in the DMZ sinc

always the threat, although it is much escalated now with N

nuclear weapons.

80. Cumings, Korea's Place in the Sun, 186.

81. DMZ Forum, "The DMZ: Description and History."

www.dmzforum.org. Don Oberdorfer lists the following as the es

900,000 Chinese, 520,000 North Korean, 400,000 United Nation

and wounded, and 36,000 U.S. deaths. This accounts only for

casualties are notoriously difficult to ascertain, but the estimates

sides, killed, wounded, or missing. An additional five million bec

Two Koreas, 9-10.

82. DMZ Forum, "Description and History."

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6o6 : DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

ideologically infused development, some positive enviro

have resulted as well. Like the accidental wildlife sanctuary

Rocky Flats Nuclear Arsenal near Denver, Colorado—a cr

the United States' Cold War activities—remained free of commercial or

private development and became a de facto (and since 2005, an officially rec

ognized) wildlife reserve. Similarly, the U.S. Navy ordnance testing ground at

Vieques, Puerto Rico also escaped development during the Cold War and now

enjoys national wildlife refuge designation. In contrast, the DMZ's official

status is still in question. Paradoxically, continued tensions and potential rec

onciliation between the two Koreas means that the DMZ's future hangs in

the balance.

In light of this question, North and South Korean politicians, activists, and

scientists, as well as researchers from neighboring nations and across the globe,

have begun turning their attention toward the DMZ. Kim Kwi-gon, a professor

at Seoul National University, characterized the area as "a global treasure house

of ecosystems. That treasure house is in danger, however. 5 One clear indi

cation of this is the status of the migratory stopover sites for white-naped cranes.

A research team based in Japan published a study in Conservation Biology in 1996

that tracked the migratory paths of cranes between southeastern Russia, China,

and Japan between 1991 and 1993. The study echoed the findings of George

Archibald reported in the Audubon article (discussed above), concluding that for

the birds to survive, their stopover sites—many of which were in or around the

marshlands of the DMZ—must be preserved. The study discovered that the

"number of days cranes spent in or near the DMZ shows that habitat conser

vation of those sites is critical for crane migration."84 "Without proper conser

vation measures," the study reported, "stopover sites may become weak links in

the chain of migration and, if broken, will likely signal the end of the wild crane

populations that rely on them."85

The study's authors identified in 1993 a number of issues threatening the

sites, including the "Team Spirit" military exercises that South Korean and U.S.

armed forces had been conducting each spring since 1976.86 Furthermore, the

authors speculated that the "potential unification of [North Korea] and [South

83. Kwi-Gon Kim and Dong-Gil Cho, "Status and Ecological Resource Value of the

Republic of Korea's De-Militarized Zone," Landscape and Ecological Engineering 1 (2005): 3.

84. Hiroyoshi Higuchi et al., "Satellite Tracking of White-Naped Crane Migration and the

Importance of the Korean Demilitarized Zone," Conservation Biology 10 (June 1996): 809-10.

The natural marshlands in and near the DMZ and the agricultural areas in the CCZ served as

the primary habitat and feeding grounds for the migrating cranes.

85. Ibid., 806. Nine of the fifteen cranes tracked over a three-year period used the DMZ as

a long-term (more than ten days) stopover site each year, with five of them spending over half

their migration period in the DMZ.

86. Ibid., 810. The "Team Spirit" maneuvers were designed as defensive and "show-of

force" actions intended to deter North Korean aggressions across the DMZ. They were

conducted annually for eighteen years until they were suspended in hopes of encouraging

North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program and engage in talks. Although Team

Spirit continued to be scheduled through 1996, the last one was conducted in 1993.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 607

Korea] will open the areas to swift development" and pointed to a Korean

Research Institute for Human Settlements plan that proposed increased "infra

structure, water resources, and economic growth in the 10 [South Korean]

counties that border the DMZ." At the time of publication, a road through the

Cholwon basin, one of the main migratory stopover sites, was already under

construction. The researchers indicated that the development's "impact on the

cranes has been unmitigated."87

The journal Ecological Economics published a study in 2003 that similarly

linked development to the decline of crane viability. The authors argued that

"willful industrial expansion" was at the root of the loss of winter habitat.88

They also suggested that although the cranes' habitat in the DMZ had provided

them some protection, it remained "very fragile." One reason was that "the

local farmers regard the cranes as a potential threat [to] their livelihood rather

than as an ecological member sharing the same ecosystem resources." Other

reasons included landholders' support for development and their legal claim to

property rights, the difficulty of imposing official policies for wildlife protection

(despite public support for such measures), and the lack of "organized public

commitment" to counter what the authors called "the persistent threat of

development."89

One solution they proposed identified several "non-market benefits" associ

J r\ A It T Tl.

aiLU vv Iuii uiiv- ui aiiuo aiiu an uiiuuvuiujjuu u/mu/. i iiu auuivii^ DD uiiciu

ecotourism may present the best possibility. This option

On one South Korean-ran tour to the DMZ, participants

tary inspection post to enter the civilian control zo

encounter a "farm and forestry landscape that is in sharp

environment where they live or have seen en route to th

upon seeing a peaceful pastoral valley of rice paddies an

amidst flowing streams and springs. Only the presence of

and some rains evidence the past wartime violence."90 A

n TT r 1 Û/1 rr n rl t-hi t- t-li ü (•niiripfp /~v n rvnrHnnlnr ft*ir\ tirûf û tn r* p 1-1 t j l n t-üfort-ü/1 m

seeing the old battlefields and war monuments—because they did indeed sign up

for the "Battle-Field Monument" tour—the serene, undeveloped landscape was

an unexpected bonus that added value to the journey. To maintain the level of

87. Ibid., 810. Construction on the road was not completed until 2003, after a decade of

heightened tensions. Both a highway and a railroad now exist at this point between the two

Koreas. Whereas South Koreans take advantage of them, few North Koreans go south on the

road. See Tom O'Neill, "Due North: A Brief Visit above the DMZ," National Geographic (July

2003): 22, and James Brooke, "Crossing the Line to Korean Détente," International Herald

Tribune, 24 October 2005; available from http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/10/24/news/

dmz.php (accessed 4 May 2007).

88. Kun H. John, Yeo C. Youn, and Joon H. Shin, "Resolving Conflicting Ecolocial and

Economic Interest in the Korean DMZ: A Valuation Based Approach," Ecological Economics 46

(August 2003): 174.

89. Ibid., 174.

90. Ibid., 175.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6o8 : DIPLOMATIC HISTORY

.. :i

w

, J^lkV/liW

Figure 4: Keepsake key chain commemorating a DMZ visit. The image depicts a deer a

crane among leafy foliage. South Korean entrepreneurs are cashing in on the DMZ's nat

reputation—and its potential. Key chain in possession of author (who could resist?). Photo

author.

satisfaction for these tourists, the authors contended, the landscape must rem

in its present, undeveloped state91 (see Figure 4).

Tens of thousands visit the DMZ each year. Many go to honor Korean Wa

dead; others go out of curiosity to witness the last vestige of the Cold War.

April 1996, the New York Times reported that despite official South Korea

warnings of the "extremely dangerous" conditions at the DMZ due to recen

incursions by North Korean soldiers, "busloads of tourists" continued to trav

to Panmunjom to visit the armistice site.92 Since then, a variety of tours has be

developed, highlighting other points of interest in the DMZ and its surround

areas. Just north of the divide, the North Korean government partnered wi

Hyundai Corporation, a South Korean conglomerate, to offer a three-d

91. Ibid., 175. In 2004 the National Tourism Organization in South Korea proposed a

ecotourism center in Cholwon, an area renowned for its bird life. Development associated w

such a tourist destination has already begun. See Onishi, "Does a Tiger Lurk."

92. Andrew Pollack, "At the DMZ, Another Invasion: Tourists," Alew York Times (late e

10 April 1996, A10. See also Colin Woodard, "DMZ Holiday," Bulletin of the Atomic Scienti

54 (May-June 1998): 12-14, and Chester Dawson, "Popping up to the DMZ," Business We

27 October 2003, 136.

This content downloaded from

176.63.20.249 on Wed, 27 Jan 2021 20:16:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Life in the DMZ : 609

nature-based tour of Mount Kumgang.93 South Koreans access the sacred

mountain by means of a highway completed in 2003—the same road that the

authors of the Conservation Biology article deemed harmful to the cranes.

Although the effect on the cranes and other wildlife has yet to be adequately

studied, development is moving apace along the northern border of the DMZ. In

addition to the Mount Kumgang trips, which serve approximately a thousand

South Korean tourists each day, Hyundai is adding golf courses, hotels, and other

tourist amenities to the surrounding North Korean landscape.94 According to an

article in the International Herald Tribune, the Mount Kumgang area "is rapidly

becoming a South Korean tourist playground." The Hyundai Corporation is also