Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HIGHLIGHTER Reviewed Article 19-Prevention of Infective Endocarditis

Uploaded by

neeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HIGHLIGHTER Reviewed Article 19-Prevention of Infective Endocarditis

Uploaded by

neeCopyright:

Available Formats

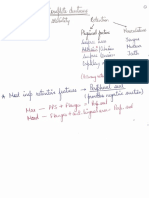

Clinical Practice

Prevention of Infective Endocarditis: Revised

Guidelines from the American Heart Association

and the Implications for Dentists

Contact Author

David K. Lam, DDS; Ahmed Jan, DDS;

Dr. Sándor

George K.B. Sándor, MD, DDS, PhD, FRCD(C), FRCSC, FACS; Email: george.sandor@

Cameron M.L. Clokie, DDS, PhD, FRCD(C) utoronto.ca

ABSTRACT

Infective endocarditis is a rare but life-threatening microbial infection of the heart

valves or endocardium, most often related to congenital or acquired cardiac defects. The

American Heart Association (AHA) recently updated its recommendations on prophylaxis

during dental procedures. The revisions will have a profound impact on both the patient

and the dental practitioner. The purpose of this paper is to review the pathogenesis and

clinical presentation of infective endocarditis and discuss the 2007 AHA guidelines and

their implications for dentists.

For citation purposes, the electronic version is the definitive version of this article: www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-74/issue-5/449.html

I

nfective endocarditis is an uncommon but American Dental Association, the Infectious

potentially life-threatening microbial in- Diseases Society of America and the American

fection of the heart valves or endocardium, Academy of Pediatrics, to review input from

most often related to congenital or acquired national and international experts on the

cardiac defects. High morbidity and mortality disease. The recommendations of this group

rates remain associated with the infection culminated in the 2007 AHA guidelines on

despite advances in diagnosis, antimicrobial prophylaxis for infective endocarditis, which

therapy, surgical techniques and manage- will have a profound impact on both patients

ment of associated complications. Since the and dental practitioners.

American Heart Association (AHA) pro- The purpose of this paper is to review

duced guidelines on the prevention of in- the pathogenesis and clinical presentation of

fective endocarditis in 1997,1 many groups infective endocarditis and discuss the new

have questioned the efficacy of antimicrobial guidelines on prophylaxis and their implica-

prophylaxis in patients who undergo dental tions for dentists.

procedures and have suggested that this rec-

ommendation be revised.2–6 Pathogenesis of Infective Endocarditis

The AHA appointed a writing group, in- Turbulent blood flow produced by certain

cluding experts in the prevention and treat- types of congenital or acquired heart disease

ment of infective endocarditis from the may traumatize the endothelium and result

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • June 2008, Vol. 74, No. 5 • 449

––– Sándor –––

Table 1 Diagnosis of infective endocarditis7 sites.6 Mediators of bacterial adherence serve as virulence

Major criteria

factors in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. Some

streptococci in the viridans group contain a lipoprotein

Positive blood culture

receptor antigen I (LraI) that acts as a major adhesin

Echocardiogram evidence of endocardial involvement to the fibrin platelet matrix of nonbacterial thrombotic

New valvular regurgitation endocarditis.6,9

Minor criteria

Predisposing heart condition Microbial Proliferation within a Vegetation

Intravenous drug use Once attached to an anatomic focus, these microor-

Fever

ganisms stimulate further deposition of fibrin and plate-

lets on their surface. Thus buried, the microorganisms

Vascular phenomena (emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts,

mycotic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, Janeway

can multiply rapidly, apparently uninhibited by host de-

lesions) fenses.6 More than 90% of the microorganisms in mature

Immunologic phenomena (glomerulonephritis, Osler’s

valvular vegetations are unresponsive to antibiotics as

nodes, Roth’s spots, rheumatoid factor) they are metabolically inactive.6,10

Isolated blood culture or serologic evidence of active

Thus, infective endocarditis arises from complex

infection interactions between the bloodstream microbial patho-

Echocardiogram findings consistent with endocarditis

gen and the matrix molecules and platelets at sites of

but not diagnostic of the disease endocardial cell damage.

Clinical Presentation of Infective Endocarditis

Signs and Symptoms

in the deposition of platelets and fibrin on the damaged The classic symptoms of infective endocarditis include

endocardium or endothelial surface. This may result in fever, anemia, positive blood cultures and heart murmur.7

the formation of sterile vegetations, a condition known as However, diagnosis must always involve a high level of

nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis.6,7 Invasion of the clinical suspicion, as these classic findings may not al-

bloodstream by microbes that can colonize this damaged

ways be present (Table 1). Other symptoms may include

site may result in infective endocarditis.

fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, anorexia and arth-

ralgia. Emboli may result in chest pain, abdominal pain,

Odontogenic Sources of Transient Bacteremia

blindness, paralysis and hematuria. Petechiae may occur

In 1909, Horder discovered an association between

on skin or mucosal tissues and linear hemorrhages may

dental health and infective endocarditis, when he noted

be visible under the nails. Osler’s (subcutaneous) nodes,

that “infection is grafted upon a previously sclerosed

endocardium... the source of the infecting agent, in most Janeway lesions (flat, nontender, red spots on palms and

of the cases, is the mouth.”8 Oral mucosal surfaces are soles that blanch on pressure) and retinal hemorrhages

populated by a dense endogenous microflora. Trauma to may also be noted.

these surfaces, particularly the gingival crevice around Laboratory Findings

teeth, releases these microbial species transiently into the • Leukocytosis with neutrophilia

bloodstream.

• Increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Transient bacteremia caused by the viridans group

• Positive C-reactive protein

of streptococci and other oral microflora commonly oc-

• Increased levels of serum immunoglobulins

curs during dental extractions, other procedures and

• Blood cultures positive for pathogen

even during routine daily activities.6,7 The frequency and

intensity of the resulting bacteremias is related to the • Positive rheumatoid factor

nature and magnitude of the tissue trauma, the density Electrocardiogram Findings

of microbial flora and the degree of inflammation or • Prolonged PR interval (caused by abscess)

infection at the trauma site. The species entering the • Silent myocardial infarction (caused by emboli in

bloodstream depends on the endogenous microflora that coronary artery)

colonize the traumatized site.

Echocardiography

Microbial Adherence • Vegetations

The focus of infection is determined by the ability of • Valvular perforations

various microbial species to adhere to specific anatomic • Other abnormalities (e.g., abscesses, pericarditis)

450 JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • June 2008, Vol. 74, No. 5 •

––– Infective Endocarditis –––

Box 1 Cardiac conditions with the highest risk of adverse important than prophylactic antibiotics for a dental pro-

outcome from infective endocarditis and for which cedure in reducing the risk of infective endocarditis.

prophylactic dental procedures are recommended6

Revised AHA Guidelines on Prophylaxis for Infective

• Prosthetic cardiac valve Endocarditis

• Previous infective endocarditis In its 2007 guidelines, 6 the AHA concluded that

• Congenital heart diseasea bacteremia resulting from daily activities is much more

- Unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease, likely to cause infective endocarditis than bacteremia

including palliative shunts and conduits associated with a dental procedure. Moreover, they con-

- Completely repaired congenital heart defect with cluded that only an extremely small number of cases of

prosthetic material or device, whether placed by infective endocarditis might be prevented by antibiotic

surgery or by catheter intervention, during the prophylaxis even if prophylaxis is 100% effective. Thus,

first 6 months after the procedureb antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended based solely

- Repaired congenital heart disease with residual on an increased lifetime risk of acquisition of infective

defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a pros- endocarditis.

thetic patch or prosthetic device (which inhibit

As a result, the revised guidelines were greatly simpli-

endothelialization)

fied. The major changes include the following: infective

• Cardiac transplantation with subsequent cardiac

endocarditis prophylaxis for dental procedures is recom-

valvulopathy

mended only for patients with underlying cardiac condi-

a

Except for the conditions listed here, antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recom- tions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome

mended for any other form of congenital heart disease. from infective endocarditis (Box 1). Antibiotic prophyl-

b

Prophylaxis is recommended because endothelialization of prosthetic material

occurs within 6 months after the procedure. axis is no longer recommended for those with any other

form of congenital heart disease.

Prophylaxis is recommended for all dental procedures

that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the peri-

Prophylaxis for Infective Endocarditis during apical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa

Dental Procedures only for patients at highest risk of adverse outcome from

Rationale for Prophylaxis infective endocarditis (Box 1). Prophylaxis is no longer

The 1997 AHA guidelines1 recommended antimi- needed for routine anesthetic injections through non-

crobial prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis infected tissue, dental radiographs, placement of remov-

among patients with underlying cardiac conditions who able prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances, adjustment

must undergo bacteremia-producing procedures. The of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic

recommendation was based on the following factors: in- brackets, shedding of deciduous teeth or bleeding from

fective endocarditis is an uncommon but life-threatening trauma to the lips or oral mucosa.

The recommended antibacterial regimens for dental

disease and prevention is preferable to treatment of estab-

procedures remain unchanged (Table 2).

lished infection; certain underlying cardiac conditions

predispose patients to infective endocarditis; bacteremia

Discussion

with organisms known to cause infective endocarditis

The vast majority of cases of infective endocarditis

is common during invasive dental procedures; antimi-

caused by oral microflora likely result from random

crobial prophylaxis is effective in preventing infective bacteremias caused by routine daily activities, such as

endocarditis in animals; and antimicrobial prophylaxis chewing food, brushing teeth, flossing, use of water irrig-

was thought to be effective in preventing infective endo- ation devices and other activities.6,7 These transient bac-

carditis associated with dental procedures in humans. teremias usually clear within 10 minutes.7 For example,

tooth brushing was found to introduce bacteria into the

Primary Reasons for Revision of the Guidelines

bloodstream in about 40% of people tested7; similarly,

Although the rationale for prophylaxis of infective

chewing paraffin or oral irrigation produced transient

endocarditis remains valid, it does not compensate for bacteremias in 50% of people.7 Guntheroth12 estimated

the lack of data demonstrating a benefit. Moreover, anti- that with normal physiologic use of the oral cavity, about

biotic prophylaxis is not risk free. Penicillins cause al- 5,376 minutes of transient bacteremias occur each month

lergic reactions among 1%–10% of patients. The risk of in the average person. Thus based on the high frequency

death from anaphylactic reaction is 5 times greater than of physiologic bacteremias and the low incidence of dental

that from treating infective endocarditis.11 Maintenance procedures preceding the onset of infective endocarditis,

of optimal oral health and hygiene may reduce the in- the odds of a case of infective endocarditis occurring

cidence of bacteremia from daily activities and is more from physiologic “seeding” of oral bacteria is 1,000 times

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • June 2008, Vol. 74, No. 5 • 451

––– Sándor –––

Table 2 Prophylactic antibiotic regimens before a dental procedure6

Dose (single, 30–60 min before procedure)

Patient group Antibiotic Adults Children

Able to take oral medication Amoxicillin 2g 50 mg/kg

Unable to take oral medication Ampicillin 2 g IM or IV 50 mg/kg IM or IV

OR

Cefazolin or ceftriaxone 1 g IM or IV 50 mg/kg IM or IV

Allergic to penicillins or ampicillin Cephalexin a,b

2g 50 mg/kg

and able to take oral medication OR

Clindamycin 600 mg 20 mg/kg

OR

Azithromycin 500 mg 15 mg/kg

or clarithromycin

Allergic to penicillins or ampicillin Cefazolin or ceftriaxoneb 1 g IM or IV 50 mg/kg IM or IV

and unable to take oral medication OR

Clindamycin 600 mg IM or IV 20 mg/kg IM or IV

Note: IM = intramuscular, IV = intravenous.

a

Or other first- or second-generation oral cephalosporin at equivalent adult or pediatric dose.

b

Cephalosporins should not be given to a patient who has a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema or urticaria with penicillins or ampicillin.

greater than after a dental procedure.12 However, the educate their patients about the changes and communi-

presence of dental disease may increase the risk of bac- cate effectively with their medical colleagues to optimize

teremia associated with these routine activities. the continued safe delivery of patient care. a

As health care providers, dentists must consider

the benefits of infective endocarditis prevention along

THE AUTHORS

with the risks of administering antibiotics: adverse drug

events, the financial cost of antibiotics, the development

Dr. Lam is the chief resident in the division of oral and maxil-

of bacterial drug resistance and medicolegal concerns. lofacial surgery and anesthesia, Mount Sinai Hospital; Ph.D.

But no matter how we weigh the risks and benefits of Harron Scholar, Collaborative Program in Neuroscience; and

prophylaxis for infective endocarditis, until prospective clinician-scientist fellow at the University of Toronto Centre

for the Study of Pain, Toronto, Ontario.

clinical trials are conducted, its true efficacy will remain

unclear.

Based on the revised 2007 AHA guidelines, 6 substan- Dr. Jan is a senior resident in the division of oral and max-

illofacial surgery and anesthesia, Mount Sinai Hospital,

tially fewer patients will meet the criteria for infective University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

endocarditis prophylaxis before dental procedures. The

new recommendations may understandably cause con- Dr. Sándor is clinical director of the graduate program in

cern at multiple levels. There will be concern among oral and maxillofacial surgery and anesthesia, Mount Sinai

patients who have previously received antibiotic pro- Hospital; coordinator of pediatric oral and maxillofacial

surgery, The Hospital for Sick Children and Bloorview Kids

phylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis before dental Rehab; professor of oral and maxillofacial surgery, University

procedures and are now advised that such prophylaxis is of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; professor at the Regea Institute

unnecessary. Moreover, there may be concerns amongst for Regenerative Medicine, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland;

and docent in oral and maxillofacial surgery, University of Oulu, Oulu,

physicians, who in the past have supported antibiotic Finland.

prophylaxis and may not be aware of the recent changes

to the guidelines. There may be concern on the part Dr. Clokie is a professor and head of oral and maxillofacial

of regulators who now must decide whether to modify surgery and anesthesia, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario.

their practice guidelines to mirror those of the current

AHA recommendations. Similarly there may be initial

resistance within certain hospitals to follow the new Correspondence to: Professor George K.B. Sándor, The Hospital for Sick

Children, S-525, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, ON M5G 1X8.

recommendations.

It is thus important for dentists to be familiar with The authors have no declared financial interests.

both the AHA guidelines and the rationale behind them.

This will allow them to alleviate their own concerns, re- This article has been peer reviewed.

452 JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • June 2008, Vol. 74, No. 5 •

––– Infective Endocarditis –––

Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology,

References Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care

1. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Bolger AF, Bayer A, Ferrieri P, and and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 2007;

others. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: recommendations by the 116(15):1736–54. Epub 2007 Apr 19.

American Heart Association. JAMA 1997; 277(22):1794–801.

7. Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Infective endocarditis. In:

2. Strom BL, Abrutyn E, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Feldman RS, Stolley PD, and Dental management of the medically compromised patient. 6th edition.

others. Dental and cardiac risk factors for infective endocarditis: a popula- Toronto: Mosby, Inc.; 2002. p. 21–51.

tion-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129(10):761–9.

8. Durack DT. Prevention of infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 1995;

3. Durack DT. Antibiotics for prevention of endocarditis during dentistry: 332(1):38–44.

time to scale back? Ann Intern Med 1998; 129(10):829–31.

9. Burnette-Curley D, Wells V, Viscount H, Munro CL, Fenno JC, Fives-Taylor

4. Durack DT. The incidence of infective endocarditis following surgical re- P, and other. FimA, a major virulence factor associated with Streptococcus

pair of a major congenital defect varied by type of heart defect. Evid Based

parasanguis endocarditis. Infect Immun 1995; 63(12):4669–74.

Cardiovasc Med 1998; 2(3):74.

10. Durack DT, Beeson PB. Experimental bacterial endocarditis. II. Survival of

5. Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Fox PC, Norton HJ, Jernigan DB, Strausbaugh

a bacteria in endocardial vegetations. Br J Exp Pathol 1972; 53(1):50–3.

LJ. Decision-making on the use of antimicrobial prophylaxis for dental pro-

cedures: a survey of infectious disease consultants and review. Clin Infect Dis 11. Gould FK, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, Fulford M, Perry JD, Roberts GJ, and

2002; 34(12):1621–6. Epub 2002 May 23. others. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working

6. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob

M, and others. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the Chemother 2006; 57(6):1035–42. Epub 2006 Apr 19.

American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association 12. Guntheroth WG. How important are dental procedures as a cause of

Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on infective endocarditis? Am J Cardiol 1984; 54(7):797–801.

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • June 2008, Vol. 74, No. 5 • 453

You might also like

- Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Key Concepts in Pathogenesis, Disease Management, and Interesting CasesFrom EverandCardiac Sarcoidosis: Key Concepts in Pathogenesis, Disease Management, and Interesting CasesNo ratings yet

- The Diagnostic and Clinical Approach To Pediatric Myocarditis: A Review of The Current LiteratureDocument12 pagesThe Diagnostic and Clinical Approach To Pediatric Myocarditis: A Review of The Current LiteratureclaudyNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update: Authors: Ronak RajaniDocument5 pagesInfective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update: Authors: Ronak RajanicositaamorNo ratings yet

- Fimmu 13 915081Document15 pagesFimmu 13 915081Zakia MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Infectivev EndocarditisDocument53 pagesInfectivev EndocarditisMoises Zagala100% (1)

- Infective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionDocument10 pagesInfective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionSarah Ariefah SantriNo ratings yet

- Periodontitis y Enfermedad CardiovascularDocument8 pagesPeriodontitis y Enfermedad CardiovascularDafne MendozaNo ratings yet

- Actualización-Endocarditis-bacteriana AmJMed 2020Document6 pagesActualización-Endocarditis-bacteriana AmJMed 2020msq.cv5919No ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis in AdultsDocument52 pagesInfective Endocarditis in AdultsBenazir SalsabillahNo ratings yet

- 325 FullDocument20 pages325 FullDessyadoeNo ratings yet

- Seminar - Infective EndocarditisDocument12 pagesSeminar - Infective EndocarditisJorge Chavez100% (1)

- Circheartfailure 120 007405Document25 pagesCircheartfailure 120 007405Al MunawarNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewDocument12 pagesOrthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewAkram AlsharaeeNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Mayocp 2019 12 008 PDFDocument16 pages10 1016@j Mayocp 2019 12 008 PDFfadmayulianiNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Artery Disease CompendiumDocument11 pagesPeripheral Artery Disease CompendiumTudor DumitrascuNo ratings yet

- Viral Myocarditis: A Paradigm For Understanding The Pathogenesis and Treatment of Dilated CardiomyopathyDocument7 pagesViral Myocarditis: A Paradigm For Understanding The Pathogenesis and Treatment of Dilated CardiomyopathyLeslie Noelle GarciaNo ratings yet

- Manejo Endocarditis en Usuarios de DrogasDocument15 pagesManejo Endocarditis en Usuarios de DrogasSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of ComplicationsDocument52 pagesInfective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complicationsmmbire@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Platelet-Streptococcal Interactions in EndocarditisDocument15 pagesPlatelet-Streptococcal Interactions in EndocarditisAnonymous bFe133Co9kNo ratings yet

- Miocarditis Review NatureDocument11 pagesMiocarditis Review NatureNox ÁtroposNo ratings yet

- Detection of Periodontal Microorganisms in Coronary AtheromatousDocument14 pagesDetection of Periodontal Microorganisms in Coronary AtheromatousRoberto GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis-Update For The Perioperative ClinicianDocument13 pagesInfective Endocarditis-Update For The Perioperative ClinicianMiguel PugaNo ratings yet

- J Jacc 2022 09 044Document17 pagesJ Jacc 2022 09 044Ivan BitunjacNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyDocument13 pagesAcute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Management of Acute Heart Failure PDFDocument11 pagesEvidence-Based Management of Acute Heart Failure PDFアレクサンダー ロドリゲスNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument18 pagesInfective EndocarditisLee Foo WengNo ratings yet

- 1st JournalDocument11 pages1st Journaloke boskuNo ratings yet

- Prophylaxis of Infective Is Current Tendencies and Continuing Controversies Lancet 2008Document8 pagesProphylaxis of Infective Is Current Tendencies and Continuing Controversies Lancet 2008Dra BeleQueen Hernandez RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia JACC Scientific Expert PanelDocument19 pagesVascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia JACC Scientific Expert PanelFlavia Ozuna SalinasNo ratings yet

- Jamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501Document12 pagesJamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501lakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Stroke GeneticsDocument13 pagesStroke GeneticsRenato RamonNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in Child AHA 2021Document13 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in Child AHA 2021Carlos Peña PaterninaNo ratings yet

- J Ejrad 2012 12 026Document8 pagesJ Ejrad 2012 12 026AnnetNo ratings yet

- Aha EndocarditisDocument52 pagesAha EndocarditisEileen MoralesNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts and Future Perspectives of Stem Cell Therapy in Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocument3 pagesCurrent Concepts and Future Perspectives of Stem Cell Therapy in Peripheral Arterial DiseaseAyushmanNo ratings yet

- Pathology and Pathogenesis of Infective Endocarditis in Native Heart ValvesDocument8 pagesPathology and Pathogenesis of Infective Endocarditis in Native Heart ValvesIrina TănaseNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 435Document25 pages2020 Article 435Carlos Peña PaterninaNo ratings yet

- Mitral Valve Prolapse Research Jacc December 2022Document17 pagesMitral Valve Prolapse Research Jacc December 2022Nox ÁtroposNo ratings yet

- RHD CHDDocument7 pagesRHD CHDAaditya MallikNo ratings yet

- A Case Report of Rare Acute Ischemic Stroke Due To Meningeal IrritationDocument7 pagesA Case Report of Rare Acute Ischemic Stroke Due To Meningeal IrritationDayu Punik ApsariNo ratings yet

- Lai 2021Document10 pagesLai 2021Илија РадосављевићNo ratings yet

- 2022 Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy and Management of Infective Endocarditis, and Its ComplicationsDocument7 pages2022 Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy and Management of Infective Endocarditis, and Its ComplicationsstedorasNo ratings yet

- Vascilar CKDDocument7 pagesVascilar CKDanggi abNo ratings yet

- Fneur 13 857640Document8 pagesFneur 13 857640Sebastian HernandezNo ratings yet

- Endocarditis ReviewDocument8 pagesEndocarditis ReviewCatherine Saenz SerranoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Update For The Diagnosis and Management of Acute Coronary SyndromesDocument13 pages2021 Update For The Diagnosis and Management of Acute Coronary SyndromescastillojessNo ratings yet

- McDonald 2009, Acute IEDocument19 pagesMcDonald 2009, Acute IETenta Hartian HendyatamaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Treatment of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery DiseaseDocument11 pagesEvaluation and Treatment of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery DiseaseMurilo Marques Almeida SilvaNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis PDFDocument6 pagesInfective Endocarditis PDFMaya WijayaNo ratings yet

- WJN 5 139Document9 pagesWJN 5 139Dzikrul Haq KarimullahNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in Controlling Sternal Wound Infection After Cardiac Surgery and Measures To Enhance Sternal HealingDocument16 pagesRecent Developments in Controlling Sternal Wound Infection After Cardiac Surgery and Measures To Enhance Sternal Healingapi-725606760No ratings yet

- Kidney Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis JUL 2022Document15 pagesKidney Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis JUL 2022Diego Ignacio González MárquezNo ratings yet

- Strokeaha 120 032704Document11 pagesStrokeaha 120 032704Norlando RuizNo ratings yet

- Cafaro 2023 Cardiovascular Risk in Systemic AutDocument2 pagesCafaro 2023 Cardiovascular Risk in Systemic AutSilvia PeresNo ratings yet

- Colchicine in Coronary Artery Disease (NEJM, 2020) PDFDocument10 pagesColchicine in Coronary Artery Disease (NEJM, 2020) PDFthe_leoNo ratings yet

- Atherosclerosis 2Document6 pagesAtherosclerosis 2Gustivanny Dwipa AsriNo ratings yet

- Infectious EndocarditisDocument49 pagesInfectious EndocarditisDennisFrankKondoNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis in Pediatric Patients in A Tertiary Care Hospital PakistanDocument4 pagesInfective Endocarditis in Pediatric Patients in A Tertiary Care Hospital PakistanPaul HartingNo ratings yet

- Myocarditis : Lori A. Blauwet, Leslie T. CooperDocument15 pagesMyocarditis : Lori A. Blauwet, Leslie T. CooperHARBENNo ratings yet

- Increasing Evidence For An Association Between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument3 pagesIncreasing Evidence For An Association Between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular DiseaseIrsyadNo ratings yet

- FS ChildhoodToothDecay ENDocument2 pagesFS ChildhoodToothDecay ENneeNo ratings yet

- HIGHLIGHTER Article #10Document13 pagesHIGHLIGHTER Article #10neeNo ratings yet

- HIGHLITYRT CA8 Informed ConsentDocument4 pagesHIGHLITYRT CA8 Informed ConsentneeNo ratings yet

- Prep Doctors Internationally Trained Dentists Upskilling ProgramDocument20 pagesPrep Doctors Internationally Trained Dentists Upskilling ProgramneeNo ratings yet

- CSV 34488726Document2 pagesCSV 34488726neeNo ratings yet

- Highlighter Info Consent 2 Art.17Document3 pagesHighlighter Info Consent 2 Art.17neeNo ratings yet

- A9 Anaesthesia OutpatientDocument7 pagesA9 Anaesthesia OutpatientneeNo ratings yet

- Resto - Non Carious Lesions, Enamel & Dentinal CariesDocument28 pagesResto - Non Carious Lesions, Enamel & Dentinal CariesneeNo ratings yet

- EmbryologyDocument10 pagesEmbryologyneeNo ratings yet

- Medical Compromise SummeryDocument4 pagesMedical Compromise SummeryneeNo ratings yet

- Prostho Materials - Alooys, Porcelain & CeramicsDocument13 pagesProstho Materials - Alooys, Porcelain & CeramicsneeNo ratings yet

- RCDSO COVID19 Managing in Person CareDocument13 pagesRCDSO COVID19 Managing in Person CareneeNo ratings yet

- Immune CellsDocument4 pagesImmune CellsneeNo ratings yet

- Ferrule and BleachingDocument6 pagesFerrule and BleachingneeNo ratings yet

- Bleeding SummaryDocument2 pagesBleeding SummaryneeNo ratings yet

- Principles of Pharma + ANS PharmacologyDocument25 pagesPrinciples of Pharma + ANS PharmacologyneeNo ratings yet

- Anti - HypertensivesDocument8 pagesAnti - HypertensivesneeNo ratings yet

- Tooth Preparation - Cavities, Indirect Restoration and CrownDocument9 pagesTooth Preparation - Cavities, Indirect Restoration and CrownneeNo ratings yet

- Endodontic DiagnosisDocument7 pagesEndodontic DiagnosisneeNo ratings yet

- Pharma - MiscellaneousDocument9 pagesPharma - MiscellaneousneeNo ratings yet

- CNS PharmacologyDocument8 pagesCNS PharmacologyneeNo ratings yet

- Endodontic MicrobiologyDocument2 pagesEndodontic MicrobiologyneeNo ratings yet

- Review of Selected Topics in Removable ProsthodonticsDocument144 pagesReview of Selected Topics in Removable ProsthodonticsneeNo ratings yet

- Prostho - CD and FPDDocument13 pagesProstho - CD and FPDneeNo ratings yet

- Prostho - Occlusion & RPDDocument12 pagesProstho - Occlusion & RPDneeNo ratings yet

- Gypsum + Alloys ClassificationDocument6 pagesGypsum + Alloys ClassificationneeNo ratings yet

- Prosthodontics 1Document13 pagesProsthodontics 1neeNo ratings yet

- (DR - Anas #3) Elastic-Impression-MaterialsDocument36 pages(DR - Anas #3) Elastic-Impression-MaterialsneeNo ratings yet

- Prosthodontics 9Document20 pagesProsthodontics 9neeNo ratings yet

- Prosthodontics 2Document22 pagesProsthodontics 2neeNo ratings yet

- Asthma Vs BronchitisDocument4 pagesAsthma Vs BronchitisEmma CebanNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Plan (RMP) - Pharmacovigilance TutorialsDocument4 pagesRisk Management Plan (RMP) - Pharmacovigilance Tutorialsvinay patidarNo ratings yet

- Epiglottitis - AMBOSSDocument10 pagesEpiglottitis - AMBOSSSadikNo ratings yet

- Cholerae O1 Causes The Majority of Outbreaks WorldwideDocument3 pagesCholerae O1 Causes The Majority of Outbreaks Worldwidefairuz89No ratings yet

- Pneumonia MCQDocument9 pagesPneumonia MCQrumi bhandariNo ratings yet

- Blok-22-Meningitis-Tuberkulosis Fakhrurrozi PratamaDocument16 pagesBlok-22-Meningitis-Tuberkulosis Fakhrurrozi PratamaFakhrurrozi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Gas GangreneDocument6 pagesGas GangreneIwan AchmadiNo ratings yet

- Critical Jurnal Review: Pendidikan Tata Rias Fakultas Teknik Universitas Negeri Medan 2020Document4 pagesCritical Jurnal Review: Pendidikan Tata Rias Fakultas Teknik Universitas Negeri Medan 2020Silvia NandaNo ratings yet

- Checklist ChildbearingDocument3 pagesChecklist ChildbearingChristine CornagoNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Lesson Plan 2 (Nursing Education)Document11 pagesMedical Surgical Lesson Plan 2 (Nursing Education)Charan100% (3)

- PhenylketonuriaDocument1 pagePhenylketonuriaHolly SevillanoNo ratings yet

- Common Complications of Active TuberculosisDocument2 pagesCommon Complications of Active TuberculosisNaila AfzalNo ratings yet

- Q3 - LESSON PLAN IN HEALTH8 Cot Final NEW PPST STANDARDDocument9 pagesQ3 - LESSON PLAN IN HEALTH8 Cot Final NEW PPST STANDARDjuvelyn abuganNo ratings yet

- Act 342 Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988Document26 pagesAct 342 Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988Adam Haida & Co100% (1)

- Ayurvedic Management of Pilonidal Sinus2Document32 pagesAyurvedic Management of Pilonidal Sinus2drhemanttNo ratings yet

- RCDSO Medical History QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesRCDSO Medical History QuestionnaireFusionIntenseNo ratings yet

- Radionic CardsDocument2 pagesRadionic CardsRoberta & Thomas NormanNo ratings yet

- List of DiseasesDocument7 pagesList of DiseasesLoveleen SinghNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY PheumoniaDocument5 pagesCASE STUDY PheumoniaEdelweiss Marie CayetanoNo ratings yet

- Asma PDFDocument2 pagesAsma PDFAzizah Hana RNo ratings yet

- Impak Krisis Covid19 Terhadap Sektor PertanianDocument8 pagesImpak Krisis Covid19 Terhadap Sektor PertanianfatinNo ratings yet

- Lapitan NCP MyelomeningoceleDocument4 pagesLapitan NCP MyelomeningoceleRea LapitanNo ratings yet

- My Oral Proyect: Student: Garcia Ynoñan Jesus EnriqueDocument10 pagesMy Oral Proyect: Student: Garcia Ynoñan Jesus EnriqueJesúsEnriqueGarciaNo ratings yet

- Initial Antimicrobial Management of Sepsis: Review Open AccessDocument11 pagesInitial Antimicrobial Management of Sepsis: Review Open AccessblanquishemNo ratings yet

- Cyndy Trimm Healing PrayerDocument5 pagesCyndy Trimm Healing Prayermazzagra100% (3)

- Gutierrez, Winell M. 5 NOVEMBER 2019 BSN Ii-3 Rle-Camantiles Rhu PoliomyelitisDocument6 pagesGutierrez, Winell M. 5 NOVEMBER 2019 BSN Ii-3 Rle-Camantiles Rhu PoliomyelitisWinell GutierrezNo ratings yet

- SARA Alert Product FS 6-23-2020Document2 pagesSARA Alert Product FS 6-23-2020NEWS CENTER MaineNo ratings yet

- 10) One Word That Can Save Your LifeDocument4 pages10) One Word That Can Save Your LifeParesh PathakNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics MCQs - DR Ranjan Singh - Part 1Document10 pagesPediatrics MCQs - DR Ranjan Singh - Part 1k sagarNo ratings yet

- ARFA HospitalDocument3 pagesARFA HospitalHazel BandayNo ratings yet