Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aleut Semaphore Signals

Uploaded by

Thoth IbisOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aleut Semaphore Signals

Uploaded by

Thoth IbisCopyright:

Available Formats

Aleut Semaphore Signals

Author(s): Jay Ellis Ransom

Source: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 43, No. 3, Part 1 (Jul. - Sep., 1941), pp.

422-427

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/663141 .

Accessed: 21/06/2014 01:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to American Anthropologist.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEUT SEMAPHORE SIGNALS By JAY ELLIS RANSOM

ABOUT 1900 Afenogen Ermeloff, Fox Island Aleut native of Umnak,

Alaska, was trapping on one of the Islands of the Four Mountains at

roughly 170 degrees west longitude and 53 degrees north latitude in the Ber-

ing Sea. He and his partner were trapping on adjacent islands separated by

a narrow, tide-rip channel over which verbal communication was possible by

raising the voice.

Sometime during the course of the winter's operations a terrific gale

arose at a time when Afenogen wanted very much to effect communication

with his partner. Standing on opposite sides of the channel, both natives ges-

ticulated and shouted, but the sound of their voices was carried away by the

force of the storm.

Realizing that in cases of emergency, or when conditions prevented easy

access between two communicants, a means of effecting favorable communi-

cation might prove of value, Afenogen decided to develop some sort of sema-

phore wig-wag series which could be used to spell out messages in his native

Aleut language.

Two things enabled him to reach this conclusion. First, in 1828 Bishop

Ivan Veniaminoff began the study of the Aleut language and reduced it to

writing by adapting Russian symbols to Aleut phonetics. In his ten years of

labors among the Aleuts he erected schools and churches and, besides teach-

ing the speaking, reading and writing of Russian to the natives, taught them

to use their own language in its written form. No rules of spelling were de-

vised, except in Veniaminoff's private consistency of transcription, nor

needed where the script was wholly phonetic. Religious books were pub-

lished in Russia and distributed through the islands, and via the agencies of

the Russian church the Aleut written language spread rapidly to common

use.

Second, it is probable that Afenogen received his idea for a semaphore

code from observation of the United States Coast Guard at Unalaska, and

on tour, at Umnak. Especially at the latter place where all ships must an-

chor a half mile out from shore, it is likely that at various times wig-wag

conversations were carried on between ship and shore. It is conceivable, but

doubtful, that Afenogen evolved the semaphore-code concept independently

of any extraneous stimuli, simply because he possessed a written language.

Where the Coast Guardsmen were familiar to the native population, the

observations by keen Aleut minds would undoubtedly have solved the com-

munication problem.

From whatever source Afenogen received the stimulus for reducing his

422

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RANSOM] ALEUT SEMAPHORE SIGNALS 423

written language to code symbols, it is obvious that his signs were independ-

ently invented and bear no relationship to the American semaphore.

After returning home to Umnak Village from his winter's sojourn on his

trapping grounds, Afenogen devoted approximately two weeks, according

to my informant, to working out, perfecting, and practicing with his partner

a wig-wag code. This is no easy task, as anyone who has mastered the use of

the American Boy Scout wig-wag knows. Compared with the American code

his signals are awkward to produce and not capable of the speed of the

former.

It is very probable that Kroeber's theory of stimulus diffusion finds cor-

roboration here. The idea of code communication reached the Aleuts with-

out any of the American symbols. Furthermore the construction of the code

is on a radically different principle. The American semaphore is built on a

regular succession of arm movements which, taken in order, were assigned

alphabetical equivalents from A to Z. No attempt was made to form the

signals upon the configuration of the letters themselves. But Afenogen, pos-

sessed of a written language and the stimulus for reducing it to signals,

utilized the simple scheme of coordinating arm movements with the most

characteristic lines that make up the letters of Aleut script. As far as possi-

ble Afenogen attempted to reproduce his letters by arm position leaving the

uncertain letters v, 6, i, q, c, ya, and x to inverse arm positions of some other

letter, or to independent invention of a recognizable position.

Once having arrived at a satisfactory complex of symbols he taught oth-

ers the new means of communication. Within a surprisingly short time the

entire male population, youths and adults, were using the code for all sorts

of communication. Even today it is not infrequent that two men at opposite

ends of the village can be seen wig-wagging back and forth, communicating

without the necessity of verbal contact.

The informant who gave me the code also stated that in recent years the

American Morse code was being put in use for night communication by

means of flashlights. The language used, however, is English and principally

by the younger generation who may have picked up the code from a Boy

Scout Handbook in the government school library. The concept of night

communication was, obviously, an outgrowth of the daylight semaphore and

came, seemingly, at a later date when there was no necessity for the use of the

Aleut language. As far as my informant knows, no formal instruction by any

white person introduced the Morse.

The native Aleuts took up the written language with great enthusiasm,

more so than any other Alaskan native people with whom the early mission-

aries came into contact, and the written language is used widely today.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

424 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. S., 43, 1941

Essentially it is male property although a few women are able to read it.

All village bulletins and church orders are posted on a central bulletin

board. Today adult Aleuts keep comprehensive diaries, especially when

away trapping. They are excellent letter writers, maintaining constant com-

munication with their distant friends and relatives, not a few of whom jour-

ney as far distant as Seattle, more generally ranging from Attu to the Pribo-

loffs, Bristol Bay, and Kodiak. The older natives write entirely in the Aleut

language, sometimes in Russian, less frequently in English. The youngsters,

through the recent influence of the United States Government schools write

most of their letters in English although among themselves, that is, among

the boys, they may, and frequently do, write the script taught them by their

parents without the sanction of the Federal schools.

Following is a description of the Aleut semaphore code. The Russian let-

ters are followed by their phonetic equivalents.

Russian Phonetic

Letter Equivalent

A a Left hand extended horizontally at side, right hand

over left chest at shoulder.

B v *Left arm extended horizontally at side, right finger

tips on right ear tip.

F, 1 'y,'Y Left arm extended horizontally at side. (This is ob-

viously equal to the written Russian symbol in which

the body represents the vertical stroke and the arm

the horizontal.)

A Left arm horizontal at side, right fingers on right hip.

H i Both arms horizontal at side, right elbow bent down

at a 90 degree angle.

K k Right hand across body down at 45 degrees; left

hand extended up to side at 45 degrees. (The posi-

tions represent the two oblique strokes of the letter

K. See Boy Scout letter I.)

K** q Both arms horizontal at sides; left elbow bent up at

90 degrees, right bent down at 90 degrees.

JI 1, 1 Right hand down at side, extended at 45 degrees.

The position of arm and body is almost identical

with the ordinary strokes of the Slavonic L.)

* Russian letters which do not occur in Aleut

proper but are used to spell words of Russian

or English derivation. ** "Barred" K.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Y a:Satar

SK

CATXA •

I catch d cknow

-Ntc

*

c a i"O boat s

ALEUTr SEMAPHORE TEATS

i~-i -._!

:.-I:::::_iii

:--i-ii:-ii:-iiiiii-iSiiiii

i~r r~ L ."

-~FS

ALEUT

toE MA/APH&/

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RANSOM] ALEUT SEMAPHORESIGNALS 425

M m Both arms extended downward at sides at 45 de-

grees. (Arms plus body represent the strokes of the

capital M. See Boy Scout letter N.)

H n Both arms at fullest extension above head. (Prob-

ably represent the vertical strokes of the letter.)

Hr 13 Right arm fully extended above head. (Either arm

may be used depending on which is easiest to make

from the preceding letter. Probably represents the

upward curl stroke which Veniaminoff diacritically

attached to the ordinary N to distinguish it pho-

netically.

O,y o,u *Fingertips each hand meet above head, arms de-

limiting a circle.

II p, b *Right arm extended horizontally at side. (Probably

that part of the Russian II which is characteristic and

different from the I.)

P r *Left, or right, finger tips to cranium above left, or

right, ear. (Either arm may be used as there is no

distinction except ease of formation. Obviously rep-

resents the Russian P.)

C s Both arms extended horizontally at sides, elbows

bent up at 90 degrees. This signal may represent the

Russian sh (III), considering both arms in relation

to the head. Aleut S is intermediate between pho-

netic c and s, the former being equivalent to the Rus-

sian m.)

T t Both arms extended horizontally at sides. (Boy

Scout letter R. The code representation is close to

the actual T.)

"I tc Right arm horizontal, elbow bent up at 90 degrees.

(Unmistakably the Russian 'cha'.)

D f *Both hands to hips, palms up, finger tips touching.

(The body represents the vertical stroke through the

circle delimited by the arms.)

8, IO w, yu Left finger tips to cranium above left ear, right hand

palm up to right hip, finger tips touching. (This is

very close to the script appearance of a figure eight

which is the old form mostly used. The 8 alternates

today with y in Aleut for this phonetic and is of

Slavonic antiquity.)

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

426 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N.s., 43, 1941

HI ya Both arms horizontal at sides, elbows bent down at

90 degrees. (Represents no script letter.)

X x Left arm up at side extended at 45 degrees, right arm

down at side at 45 degrees. (Boy Scout letter L.

Arms represent the cross in relation to the body of

ordinary X.)

X*** x Both arms horizontal at sides; right elbow up at 90

degrees, left down at 90 degrees. (Represents no

script letter but is the inverse of q.)

r completion Both hands passed back and forth several times im-

mediately in front of the breast. This sign concludes

every message, and also represents the final Russian

hard sign, r, which is silent but written after every

final consonant of Aleut words. This sign is not used

in modern Russian spelling having been discarded

when the script was modernized but is retained in

all church books still using the Slavonic script. Hence

its use in Aleut since the most recent Aleut books

date back to 1906 and the church books prior to

1898. In normal text Aleut words are rarely sepa-

rated from each other, and this sign serves to dis-

tinguish between words. Words ending on vowels are

separated by one space.

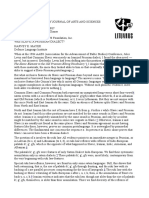

The enclosed series of photographs were made of Ardelion Ermeloff, a

relative of Afenogen, who has been convalescing in the Marine Hospital in

Seattle, Washington, from tuberculosis. Artie, as he is familiarly known,

knew Jochelson, who used his father as one of his principal informants at

Umnak. He himself was my most valued informant in 1936 when I first be-

gan the study of Aleut at Nikolski, Umnak Island, Alaska. He is much inter-

ested in his own language and the preservation of ethnologic values, and like

many of the older natives reads and writes Russian, Aleut, and English. The

latter language he has taught himself.

A study of these photographs discloses certain fundamental differences

in Artie's hand positions from those employed by users of the American

semaphore code. These differences may be of cultural significance and there-

fore I wish to draw attention to them.

It will be noted in the majority of positions that Artie has his hands palm

up. Users of the American system normally run through their signals palm

down. In letters m and t where a choice of palm position might have been

***X with invertedbrevity mark.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RANSOM] ALEUT SEMAPHORE SIGNALS 427

made either way, Artie placed his hands palm down, but upon other occa-

sions in forming the signal t, he held his hands palm up.

The position and use of the fingers is interesting for the delicate touch

made by the finger tips against those portions of the body where contact is

called for by the signal. In letter f Artie touches his hip only with the tips of

his fingers on hands held palm up whereas the average American loosely

doubles his fists and plants them firmly on his hips.

Certain words have become conventionalized by use in a rapid shifting

of the arms through their positions without recourse to the normal slight

pause following each letter. Aleut yam, meaning yesterday, is produced vir-

tually in one motion. Such conventionalizations are comparable to the

American semaphore signaled 'turn' which may be performed by one con-

tinuous motion. Needless to say these patterns are the result of a complex of

signals which flow easily one into the other and play no important part in

the code language.

A strict adherence to phonetic spelling is not attempted. It is of linguistic

interest to note that a single signal is used to represent the medial and velar

gamma while two distinct signs are used for the corresponding surd phonet-

ics, which leads one to postulate that a semantic association is more impor-

tant in the latter case.

In summarizing the development of the Aleut Semaphore Code three

factors contributed to its origin. First there had arisen in historic times a

written language which the Aleuts took up enthusiastically to fill some unex-

plained felt want in their daily lives. Secondly, the basic idea of code com-

munication serving as a stimulus to set off the inventive ingenuity reached

the Aleuts by probable diffusion through the Coast Guard within the twen-

tieth century. And third, and very likely the most important single cause of

development, was the economic and environmental necessity which demand-

ed solution of a problem in communication. This problem may have existed

prior to the arrival of the appropriate stimulus, probably as a felt but non-

verbalized need, in which case the arrival of the stimulus served to set off the

resultant reaction leading to a solution.

For nearly two centuries the Aleuts have been in continuous association

with white civilization, not always of the highest type, and their present

culture is a curious blending of elements from widely divergent sources. It is

therefore safest to assume that this form of communication is the direct re-

sult of stimulus diffusion rather than independent evolution although the

form which the resulting product took may be attributed to the latter ori-

gin.

SEATTLE. WASHINGTON

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.212 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 01:00:43 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- MAN D 2842 LE301 Spare Parts CatalogueDocument71 pagesMAN D 2842 LE301 Spare Parts CatalogueDilawar Ali100% (1)

- Brathwaite - History of The VoiceDocument52 pagesBrathwaite - History of The VoiceZachary Hope100% (1)

- Tom Gates: Excellent Excuses (And Other Good Stuff) Chapter SamplerDocument39 pagesTom Gates: Excellent Excuses (And Other Good Stuff) Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press75% (76)

- Wendish in Old Norse and NanlDocument33 pagesWendish in Old Norse and NanlДеан ГњидићNo ratings yet

- V 03 Lang 02Document31 pagesV 03 Lang 02Russell HartillNo ratings yet

- AAVE: A Case StudyDocument13 pagesAAVE: A Case Studylinda.mkhitaryanNo ratings yet

- The Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological RelationsFrom EverandThe Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological RelationsNo ratings yet

- The Lenâpé and Their Legends: With the complete text and symbols of the Walam olum, a new translation, and an inquiry into its authenticityFrom EverandThe Lenâpé and Their Legends: With the complete text and symbols of the Walam olum, a new translation, and an inquiry into its authenticityNo ratings yet

- The Lenâpé and Their Legends: Ethnological study of the The Lenâpé Indians in Eastern PennsylvaniaFrom EverandThe Lenâpé and Their Legends: Ethnological study of the The Lenâpé Indians in Eastern PennsylvaniaNo ratings yet

- Old EnglishDocument6 pagesOld EnglishAlejandro Serrano AntónNo ratings yet

- Old EnglishDocument6 pagesOld EnglishAlina ZbuffNo ratings yet

- The VikingsDocument11 pagesThe VikingsAkram AkbarNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Report On The Language and Mythology of The Upper ChinookDocument12 pagesPreliminary Report On The Language and Mythology of The Upper ChinookRaul CostaNo ratings yet

- A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa'adi Besalel a-LeviFrom EverandA Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa'adi Besalel a-LeviNo ratings yet

- Mayer Was Slavic A Prussian DialectDocument9 pagesMayer Was Slavic A Prussian DialectJacek RomanowNo ratings yet

- Ocs OnlineDocument290 pagesOcs OnlineJeremiah TannNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of The Yoruba LanguageDocument73 pagesA Grammar of The Yoruba LanguageTunde Karimu100% (2)

- The Universal Translator: Everything you need to know about 139 languages that don’t really existFrom EverandThe Universal Translator: Everything you need to know about 139 languages that don’t really existNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument8 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldmaximkristianNo ratings yet

- Anabasisofxeno 00 XenoDocument472 pagesAnabasisofxeno 00 XenoSumruhan GünerNo ratings yet

- Hard WordsDocument3 pagesHard WordsMarta Toma100% (1)

- Chinook Texts by Franz BoasDocument298 pagesChinook Texts by Franz Boasdelphic78100% (1)

- Travels in Translation: Sea Tales at the Source of Jewish FictionFrom EverandTravels in Translation: Sea Tales at the Source of Jewish FictionNo ratings yet

- Advent of The English Language and The Attainment of Sociolinguistic DominanceDocument10 pagesAdvent of The English Language and The Attainment of Sociolinguistic DominanceMatanmi QuadriNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary YorubaDocument722 pagesVocabulary YorubaSergio JituNo ratings yet

- Berber Addendum #8 v1Document6 pagesBerber Addendum #8 v1ام بناتيNo ratings yet

- Lad SyllablesDocument3 pagesLad SyllablesVanesa ChrenkováNo ratings yet

- Advanced English G 00 HartDocument208 pagesAdvanced English G 00 HartHarm MonieNo ratings yet

- Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New YorkFrom EverandLanguage City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New YorkNo ratings yet

- Gamkrelidze-Ivanov 1990 Indo-European PDFDocument7 pagesGamkrelidze-Ivanov 1990 Indo-European PDFmario riNo ratings yet

- Swan - Facultative Animacy in PolishDocument44 pagesSwan - Facultative Animacy in PolishJACOBNo ratings yet

- Rhea - Samuel A. - Brief Grammar and Vocabulary of The Hakkari - 1869Document39 pagesRhea - Samuel A. - Brief Grammar and Vocabulary of The Hakkari - 1869Anonymous qkhwe0nUN1No ratings yet

- Ingaevonic and JutlandicDocument3 pagesIngaevonic and JutlandicSøren RalphNo ratings yet

- Valles, J. HISTORY OF ENGLISH. (Corregido)Document16 pagesValles, J. HISTORY OF ENGLISH. (Corregido)Heisenberg KagariNo ratings yet

- Publishing 6310 Assignment 2Document6 pagesPublishing 6310 Assignment 2emdub123No ratings yet

- A Lenâpe English DictionaryDocument263 pagesA Lenâpe English DictionarynpeyrafitteNo ratings yet

- AFRICAN AMERICAN VERNACULAR ENGLISH IS NOT STANDARD ENGLISH WITH MISTAKES by Geoffrey K. PullumDocument20 pagesAFRICAN AMERICAN VERNACULAR ENGLISH IS NOT STANDARD ENGLISH WITH MISTAKES by Geoffrey K. PullumYulia GreymanNo ratings yet

- Article - N - Melodic and Temporal Characteristics of Different Gender and Age Group of Aave RepresentativesDocument5 pagesArticle - N - Melodic and Temporal Characteristics of Different Gender and Age Group of Aave RepresentativesPacho ArbelaezNo ratings yet

- The Intestines of the State: Youth, Violence, and Belated Histories in the Cameroon GrassfieldsFrom EverandThe Intestines of the State: Youth, Violence, and Belated Histories in the Cameroon GrassfieldsNo ratings yet

- Grammar 1 2017 1a Aula John WhitlamDocument57 pagesGrammar 1 2017 1a Aula John WhitlamJuliana CotiniNo ratings yet

- The Early History of The Indo-European LanguagesDocument9 pagesThe Early History of The Indo-European LanguagesewaNo ratings yet

- Vowel MovementDocument3 pagesVowel MovementIlham DinullahNo ratings yet

- Oceanic LanguagesDocument4 pagesOceanic LanguagesOliveiraBR100% (1)

- Wiley American Anthropological AssociationDocument31 pagesWiley American Anthropological AssociationDanilo Viličić AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Aramaic Lesson1-1Document4 pagesAramaic Lesson1-1Giovanni SerafinoNo ratings yet

- Old English OnlineDocument287 pagesOld English OnlineJeremiah TannNo ratings yet

- Ellis - Armenian Origin of Etruscans (1861)Document222 pagesEllis - Armenian Origin of Etruscans (1861)universallibrary100% (1)

- An Apology For The Study of Northern Antiquities by Elstob, Elizabeth, 1683-1756Document35 pagesAn Apology For The Study of Northern Antiquities by Elstob, Elizabeth, 1683-1756Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Historical View of The Languages and Literature of The SlavicNations by Robinson, Therese Albertine Louise Von Jacob, 1797-1870Document242 pagesHistorical View of The Languages and Literature of The SlavicNations by Robinson, Therese Albertine Louise Von Jacob, 1797-1870Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- English Dialects From The Eighth Century To The Present Day by Skeat, Walter William, 1835-1912Document74 pagesEnglish Dialects From The Eighth Century To The Present Day by Skeat, Walter William, 1835-1912Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Dictionary of The Chinook Jargon, Or, Trade Language of Oregon by Gibbs, George, 1815-1873Document57 pagesDictionary of The Chinook Jargon, Or, Trade Language of Oregon by Gibbs, George, 1815-1873Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Assyrian SelectionDocument16 pagesAssyrian SelectionSérgio Domingues100% (1)

- 1949 Oftedal NorwegianDocument8 pages1949 Oftedal NorwegianRoberto A. Díaz HernándezNo ratings yet

- D8 1LANT-TransactionsoftheRoyalSocietyofSADocument56 pagesD8 1LANT-TransactionsoftheRoyalSocietyofSArashlakNo ratings yet

- Pa History 1914Document366 pagesPa History 1914hgbpa100% (1)

- The Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological RelationsFrom EverandThe Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological RelationsNo ratings yet

- Evonaj mat' ves' noс television karaulil - His mother watched TV all night long. On the loss of gender as a grammatical category in Alaskan Russian - Daly 1986Document31 pagesEvonaj mat' ves' noс television karaulil - His mother watched TV all night long. On the loss of gender as a grammatical category in Alaskan Russian - Daly 1986Konstantin PredachenkoNo ratings yet

- How To Use The DLVSDocument18 pagesHow To Use The DLVSThoth IbisNo ratings yet

- (9781614512035 - Sign Languages in Village Communities) Signing in The Arctic - External Influences On Inuit Sign LanguageDocument28 pages(9781614512035 - Sign Languages in Village Communities) Signing in The Arctic - External Influences On Inuit Sign LanguageThoth IbisNo ratings yet

- The Dorset - An EnigmaDocument22 pagesThe Dorset - An EnigmaThoth IbisNo ratings yet

- On Narrative Expectations - Greenlandic Oral Traditions About The Cultural Encounter Between Inuit and NorsemenDocument45 pagesOn Narrative Expectations - Greenlandic Oral Traditions About The Cultural Encounter Between Inuit and NorsemenThoth IbisNo ratings yet

- Iron Utilization by Thule Eskimos of Central CanadaDocument13 pagesIron Utilization by Thule Eskimos of Central CanadaThoth IbisNo ratings yet

- Rcm&E 202201Document100 pagesRcm&E 202201Martijn HinfelaarNo ratings yet

- Awatani 1975Document6 pagesAwatani 1975Ilmal YaqinNo ratings yet

- Week 15 (Part 4) - Integration by Algebraic SubstitutionDocument9 pagesWeek 15 (Part 4) - Integration by Algebraic SubstitutionqweqweNo ratings yet

- Selection of Welding Process For Hardfacing in Carbon SteelDocument11 pagesSelection of Welding Process For Hardfacing in Carbon SteelKuthuraikaranNo ratings yet

- Zinc Precipitation On Gold RecoveryDocument18 pagesZinc Precipitation On Gold RecoveryysioigaNo ratings yet

- Process ParagraphDocument2 pagesProcess Paragraphshams.hussaini101No ratings yet

- Introduction To Human Anatomy and Physiology 4th Edition Solomon Test BankDocument25 pagesIntroduction To Human Anatomy and Physiology 4th Edition Solomon Test BankHeatherFisherpwjts100% (44)

- The Last Lesson NotesDocument11 pagesThe Last Lesson NotesAnvi Sameer TiwariNo ratings yet

- Ub5310 0Document157 pagesUb5310 0ronaldkwanNo ratings yet

- ACTIVITY 5 - The Different Types of ResearchDocument2 pagesACTIVITY 5 - The Different Types of Researchjohnrollin oconNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelligences - Howard Gardner (Prof - BLH)Document4 pagesMultiple Intelligences - Howard Gardner (Prof - BLH)Prof. (Dr.) B. L. HandooNo ratings yet

- Numerical MethodsDocument43 pagesNumerical Methodsshailaja rNo ratings yet

- Bykea AnalysisDocument13 pagesBykea AnalysisHamza ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Assignment-4 Solution V2Document6 pagesAssignment-4 Solution V2Junaid MandviwalaNo ratings yet

- Astm B505Document7 pagesAstm B505Syed Shoaib RazaNo ratings yet

- 0-WD110-EZ300-B2002 - Rev - 0 - Calculations For Safety Relief Valves and Silencers0Document10 pages0-WD110-EZ300-B2002 - Rev - 0 - Calculations For Safety Relief Valves and Silencers0carlos tapia bozzoNo ratings yet

- EQL671 Assignment SECS (0914)Document7 pagesEQL671 Assignment SECS (0914)sayamaymayNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Education Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesEarly Childhood Education Lesson PlanGraciele Joie ReganitNo ratings yet

- Games PDFDocument42 pagesGames PDFNarlin VarelaNo ratings yet

- Habeeb Ullah: PHD Competition Industrial and Information EngineeringDocument9 pagesHabeeb Ullah: PHD Competition Industrial and Information EngineeringEngr. Babar AliNo ratings yet

- Manual Biamp Amplifier Nov 16Document18 pagesManual Biamp Amplifier Nov 16Rachmat Guntur Dwi PutraNo ratings yet

- Are We Too Dependent On TechnologyDocument9 pagesAre We Too Dependent On TechnologySEBASTIENE MARION URBANONo ratings yet

- Las 4 - DiassDocument2 pagesLas 4 - Diassronald anongNo ratings yet

- Delhi LDC Alloation6813Document15 pagesDelhi LDC Alloation6813akankshag_13No ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument47 pagesTime Value of MoneyCyrus ArmamentoNo ratings yet

- Front Matter 2023 Dynamics of Plate Tectonics and Mantle ConvectionDocument10 pagesFront Matter 2023 Dynamics of Plate Tectonics and Mantle ConvectionScribd_is_GreatNo ratings yet

- Organ Systems Lecture 4 - Physiology/Cardiovascular System (CVS) by Casey KinnallyDocument12 pagesOrgan Systems Lecture 4 - Physiology/Cardiovascular System (CVS) by Casey KinnallyNYUCD17No ratings yet

- 2 Crisis Management Team Template (Revised)Document12 pages2 Crisis Management Team Template (Revised)Namrata Dhumatkar100% (2)