Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 7 - ME Organization

Chapter 7 - ME Organization

Uploaded by

Mariano Briones0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views12 pagesOriginal Title

Chapter 7 - ME organization

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views12 pagesChapter 7 - ME Organization

Chapter 7 - ME Organization

Uploaded by

Mariano BrionesCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

Chapter

The Maintenance and Engineering

Organization

‘Organization of Maintenance and Engineering

‘The structure for an effective maintenance and engineering organization will

vary with the size and type of organization. It may also vary with the manage-

ment philosophy of the company. But one thing must be kept in mind: the orga-

nizational structure must allow the company to meet its goals and objectives and

each unit within the company must be endowed with sufficient personnel and

authority to carry out those objectives and meet those goals.

The following structure was determined, from experience and observation, to

be the most efficient and effective one for a midsized commercial airline. For

application to large or small airlines, this structure will have to be modified; but

all of the functions identified here will have to exist separately or in combina-

tion to accomplish all of the functions and activities identified in Chap. 6 as

essential for effective operation.

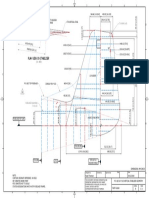

Organizational Structure

‘The basic organizational structure for our midsized airline is shown in Fig. 7-1.

There are three basic concepts underlying the structure we have defined. Two of

these come from traditional management thinking. These are the concepts of

span of control and the grouping of similar functions. The third concept is some-

what unique to aviation: the separation of production activities (maintenance

and engineering) from the oversight functions of inspection, control, and moni-

toring (quality assurance, quality control, reliability, and safety).

Span of control

The span of control coneept may be considered passé to some, but it is still a

useful concept. This concept states that a supervisor or manager can effectively

a

92

Fundamentals of Maintenance

Alera sh

Masintenanes Maintenance

eaty Amerane

Beseeing Hane [— tae

ebnne [— eens Reese sey

sty Cont

Figure7-1 Typical maintenance and engineering organization.

supervise or control three to seven people. Any less than three would be inef=

fective use of time and manpower, and any more than seven would spread the

boss too thin. In the organizational structure shown in Fig. 7-1, we have adhered

to this concept. The VP of maintenance and engineering supervises five direc-

tors. Each director has the necessary number of managers under him or her to

carry out the prescribed functions of the directorate. We find that by limiting

the number of people that a manager has to supervise, the organization's work

is divided into pieces that are more easily managed without losing the people-

to-people contact that is so necessary for a happy and efficient work force.

‘At the lower levels of the organization, where the actual maintenance work,

is performed by workers with many different skills, the span of control is usu-

ally not so narrow. A line or hangar maintenance supervisor may have as many.

as 20 or 30 of these specialists to supervise. But at the upper management

levels, we like to keep the span of control at the lower number. This is not te

say that a wider span cannot be utilized, however. All management activities

must be organized to work with the available resources and within the current

management's capabilities and philosophy.

Grouping of similar functions

The second basic concept of the organizational philosophy we are using is the

grouping of similar functions under one director, manager, or supervisor. What

‘The Maintenance and Engineering Organization 93

this comes down to is that all maintenance activities (line, hangar, and MCC) are

under one manager. All maintenance overhaul shop functions (electrical and

electronics shops, mechanical shops, hydraulics, etc.) are likewise grouped, All

inspection activities—whether it is inspecting the company’s workers, inspect

ing parts, or inspecting the suppliers of parts—are grouped into one organiza-

tion (maintenance program evaluation functions). Those handling the purchase

of supplies, those performing engineering work, and those doing the planning are

also grouped accordingly so that the managers and directors can maintain proper

surveillance and control over areas in which they have expertise.

Separation of production and oversight functions

A third concept that is applied here may be unique to the maintenance organ-

ization. Under the FAA philosophy, an airline receives certification to operate

as a commercial air transport company and that authorization is, for all prac-

tical purposes, permanent. Some foreign airlines must be recertified by their reg-

ulatory authority annually. Under the FAA rules, for an airline to be certificated,

it must have certain programs in place, including a self-monitoring function to

ensure that it is performing according to the rules (its own rules as well as

those of the regulatory authority). This alleviates the FAA from having to recer-

tify 2ach airline every year. This requirement for self-monitoring is usually in

the form of quality assurance (QA), quality control (QC), reliability, and safety

programs. Combined, these functions constitute the core of the CASS require-

ment mentioned in Chap. 6.' It is recommended, and generally practiced, that

these self-monitoring functions operate separately from the maintenance and

engineering functions they are monitoring to prevent any conflict of interest

protlems. This separation is built into the organizational structure shown in

Fig. 7-1 and is discussed below’by selective grouping.

The M&E Organizational Chart

Figcre 7-1 is the basic organizational chart for the maintenance and engineer-

ing organization of our “typical” midsized airline. We will briefly discuss each

layer and each function. The structure starts with the VP level and continues

downward with designations Director, Manager, and Supervisor as appropriate.

‘Your organization may have other titles that their operatives prefer to use but

the structure should be similar to Fig. 7-1.

General Groupings

Vice president of maintenance and engineering

The head of the entire maintenance and engineering function within the airline

should be at a relatively high level of the airline’s structure. He or she should

be directly under the head of the airline or under the head of the company’s

'Soe also FAA AC 120-79, Continuing Analysis and Surveillance System (CASS).

94

Fundamentals of Maintenance

operational activity (President, Chief Operating Officer, or whatever title is

used). The VP of M&E position should also be at the same level as the head of

flight operations (VP Flight Ops or whatever he or she is called). Flight opera-

tions and maintenance are considered to be two sides of the same coin; they com-

plement each other and carry equal weight.

‘Dhe flight operations department is responsible for conducting the air trans-

portation operations; i.e., the flying. Maintenance and engineering, on the other

hand, is responsible for delivering airworthy vehicles to the operations depart-

ment to meet the flight schedule. The M&E department is responsible for con-

ducting all scheduled maintenance, modification, etc. on the vehicles within

the specified limits of the maintenance schedule and still meet the operations

department's flight schedule. Without maintenance, flight operations would be

quite limited in their activities; without flight operations, maintenance wouldn't

have much purpose in maintaining the equipment. They need each other and the

airline needs both.

Directors of major functions

‘The five major functions shown in Fig. 7-1 are, in the order addressed in this

book, technical services (which includes engineering, planning, training, tech

nical publications, and computing); aircraft maintenance (flight line, hangar, out-

stations, and the maintenance control center); overhaul shops (for off-aireraft

maintenance, repair, and overhaul); materiel services (responsible for ordering

and maintaining supplies, handling warranties, and moving repairable and

consumable parts through the system); and maintenance program evaluation

(the monitoring activity for the organization, its workers and its suppliers). As

you can see, there is more here than just maintenance and engineering. We will

discuss each of these in more detail later.

Managers and supervisors

Within each directorate, there are several managers. Each of these managers has

a specialized area of responsibility within the overall scope of the directorate’s func:

tion. Specific activities within each manager’s area of responsibility require statis

of specialists with supervision by knowledgeable people. In some large organiza-

tions, the supervisor may need additional separation of activities or duties and

appoint “leads” or “straw bosses” to decrease his span of control to a workable size

However, for most operators, the span of control can be much wider at this level,

Manager Level Functions—Technical

Services Directorate

The technical services directorate contains numerous activities and services

that support the maintenance and inspection functions. In the typical setup of

Fig. 7-1, we have identified various activities for each directorate. Each activ

ity is under the direction of a manager. There may be further echelons of man

agement, such as supervisors and leads as necessary.

ining

‘The Maintenance and Engineering Organization 95

‘The manager of engineering is responsible for all engineering functions within

the M&E organization. This includes (a) the development of the initial main-

tenance program (tasks, intervals, schedules, blocking, etc.); (b) the evaluation

of service bulletins (SBs) and service letters (SLs) for possible inclusion into the

airline’s equipment; (c) oversight of the incorporation of those SBs and SLs that

they deem beneficial; (d) overseeing the incorporation of airworthiness directives

(ADs), the modifications that are required by the regulatory authority; (e) the

evaluation of maintenance probleme determined by the reliability program and

for problems (if any) resulting from the maintenance checks performed by main-

tenance; and (f) for establishing the policies and procedures for the M&E organ-

ization. The engineering department employs a cadre of engineering specialists,

usually enough to cover, with a high degree of expertise, any and all specialties

within the aircraft's technical realm: power plant, structures, avionics, aircraft

performance, and systems (hydraulic, pneumatic, etc.). These positions are at

the supervisor level with several engineers in each group with their own spe-

cialties, if required.

‘The engineering department is also involved in the planning of facilities (new

hangars, maintenance shops, storage facilities, buildings, etc.) for the airline,

which are to be used by the M&E organization. Although engineering usually

will not actually do the design and engineering work, they will work with the

engineering consulting firm or contractor that has responsibility for the project

to ensure that the final result meets the airline's requirements.

ion planning and control

‘The manager of production planning and control (PP&C) is responsible for

maintenance scheduling and planning. This function must plan and schedule

the manpower, parts, facilities, tools, and any special assistance required for all

maintenance or modification activities. Included in the functions of PP&C are

the following: (a) all planning activities related to maintenance and engineer-

ing (short, medium, and long term); (b) the establishment of standards for man-

hours, materiel, facilities, tools, and equipment; (c) work scheduling; (d) control

of hangars; (e) on-airplane maintenance; and (f) monitoring of work progress in

the support shops.

The manager of technical training is responsible for curriculum, course devel-

opment, administration, and training records for all formal training attended

by the M&E unit's employees. The organization coordinates any training

required outside the unit (vendor training) and coordinates with line and

hangar maintenance personnel for the development of on-the-job training and

remedial or one-time training activities. The training section must be able to

establish new and special training courses to meet the needs of the airline.

These course requirements are often the result of problem investigation by

Fundamentals of Maintenance

Technical publications

‘Computing services

Manager Level Functions—,

Maintenance Directorate

Hangar maintenance

reliability, incorporation of new equipment or modifications, or the addition of,

aircraft types to the fleet.

‘The manager of technical publications is responsible for all technical publica-

tions used by the M&E organization. The technical publications (Tech Pubs)

keeps a current list of all documents received from manufacturers and vendors,

as well as those produced in-house by the aitline. Also on record are the number

of copies, in paper, microfilm, or compact disc (CD) format, that each work

center should receive. The Tech Pubs organization is also responsible for ensuz-

ing that appropriate documents and revisions are distributed to these various

work centers. Work centers are responsible for keeping their own documents uz

rent, but Tech Pubs usually conducts periodie checks to see that this is being

done. Tech Pubs is also responsible for maintaining the main technical library

and any satellite libraries within the airline's system, including those at out

stations.

‘The manager of computing services is responsible for the definition of the M&E

organization’s computing requirements: (a) selection of software and hardware t=

be used, with usage information and requirements inputs from the individual

units; () training of maintenance, inspection, and management personnel o=

computer usage; and (¢) provide continuing support to the using organizations.

raft

The aircraft maintenance directorate has responsibility for the major aire

maintenance activities: maintenance on the flight line and maintenance

formed in the hangar. Three managers report to the director of airplane m:

tenance: one for each of these activities and one for MCC. For airlines w

different model aircraft or with two or more maintenance bases, the number

aireraft maintenance managers may be increased as necessary for the scope:

the operation.

‘The manager of hangar maintenance is responsible for compliance with

airline's policies and procedures relative to all work done on the aircraft in

hangar, such as modifications, engine changes, “C” checks (and higher), co

sion control, painting, etc. The hangar maintenance function also includes ¥

ious support shops (welding, seat and interior fabric, composites, ete.), as

as ground support equipment.

‘The Maintenance and Engineering Organization 97

maintenance

‘The manager of line maintenance is responsible for compliance with the airline's

policies and procedures relative to the work done on the aircraft on the flight line

while the aircraft is in service. Such activities include turnaround maintenance

and servicing, daily checks, short interval checks (less than “A” check interval),

and “A” checks. Sometimes, simple modifications can be done by line maintenance

in order to avoid unnecessary use of the hangar. Line maintenance may also be

utilized to perform line maintenance activities for other airlines under contract.

nance control center

‘The function known as the maintenance control center (MCC) keeps track of all

aircraft in flight and at outstations. All maintenance needs of these vehicles are

coordinated through the MCC. The MCC also coordinates downtime and sched-

ule changes with the flight department. Some airlines might have a supervisor

of line stations to coordinate outstation activities, but he or she is often part of

the home base MCC operation.

ger Level Functions—Overhaul

9s Directorate

The overhaul shops directorate consists of those maintenance shops that per-

form maintenance on items removed from the aircraft. These shops include

engine shop(s), electrical shop, electronics (or avionics) shop, and various

mechanical shops. These may be separate shops or some may be combined for

convenience, depending on the operation. Some of these shops may also perform

contract work for other airlines.

jine shops

The manager of the engine overhaul shops is responsible for all maintenance

and repair done on the organization's engines and auxiliary power units (APUs).

If more than one type engine is used, there may be a separate engine shop for

each type performing the work, but these would usually be under one senior

manager with a supervisor for each engine type. The engine build up activities

would generally come under the engine shop manager.

‘Secirical and electronics (avionics) shops

The manager of electrical/electronics shops is responsible for all off-aircraft

maintenance of electrical and electronics components and systems. There are

a variety of components and systems in this field with wide variations in the

equipment and in the skills needed to address them. There may be several

shops (radio, navigation, communications, computers, electric motor-driven

components, ete.) with separate supervisors. Shops are combined at times,

98 Fundamentals of Maintenance

however, to optimize manpower and space and to reduce test equipment inven-

tories.

Mechanical component shops

Structures

The manager of mechanical component shops has responsibilities similar to

‘those of the manager of avionics shops. The only difference, of course, is that

these shops would address mechanical components: actuators, hydraulic systems

and components, aircraft surfaces (flaps, slats, spoilers), fuel systems, oxygen.

pneumatics, ete.

‘The structures shop is responsible for maintenance and repair of all aircraft

structural components. This includes composite material as well as sheet metal

and other structural elements.

Manager Level Functions—Materiel Directorate

Purchasing

Stores

Inventory contro!

‘The materiel directorate is responsible for the handling of all parts and supplies

for the M&E organization: (a) purchasing; (b) stocking and distribution (stores):

(0) inventory control; and (d) shipping and receiving of parts and supplies used

by the M&E organization. This includes not only the parts and supplies used

in the maintenance, servicing, and engineering of the aircraft but also the sup-

plies used for the administration and management of M&E (.e., office supplies,

uniforms, etc.)

‘The manager of purchasing is responsible for buying parts and supplies and

tracking these orders through the system. This begins with the initial issue of

parts when a new aircraft is added to the fleet and a continual replenishment

of those parts based on usage. The purchasing unit is also responsible for ham

dling warranty claims and contract repairs.

‘The manager of stores takes responsibility for the storage, handling, and

tribution of parts and supplies used by the maintenance personnel in

hangar, and shop maintenance activities. Stores areas, or parts issue points,

placed near the various work centers to allow mechanics quick access to p:

and supplies and to minimize the time spent obtaining those parts and supp!

‘The manager of inventory control is responsible for ensuring that the parts

supplies on hand are sufficient for the normal, expected usage rate with

‘The Maintenance and Engineering Organization 99

tying up excessive funds in nonmoving items and without running out of stock

too soon or too often for commonly used items.

Shipping and receiving

‘The manager of shipping and receiving is responsible for packing, waybill

preparation, insurance, customs, ete. for outgoing materials, as well as customs

clearance, unpacking, receiving inspection, tagging, etc. for incoming materials.

‘This includes all parts being shipped into and out of the airline.

Manager Level Functions—Maintenance Program

Evaluation Directorate

‘The maintenance program evaluation (MPE) directorate is an organization

tasked with monitoring the maintenance and engineering organization. The

MPE unit is responsible for the CASS activities. The unit’s functions include

quality assurance, quality control, reliability, and safety.

Quality assurance

‘The manager of quality assurance is responsible for assuring that all units of

MQ&E adhere to the company policies and procedures as well as FAA require-

ments. The manager of QA sets the standards for the M&E operation, and the

QA auditors ensure compliance to those standards through yearly audits. Quality

assurance is also responsible for auditing outside suppliers and contractors for

compliance with the company’s, as well as the regulatory authority's, rules and

regulations.

Quality control

Reliability

‘The manager of quality control is responsible for conducting routine inspections

of maintenance and repair work, certifying maintenance and inspection per-

sonnel, and management of the required inspection items (RIIs) program. This

latter function involves the identification of RUls and the certification of spe-

cific personnel authorizad to inspect and accept the work. The QC organization

is also responsible for the calibration of maintenance tools and test equipment

and performs or oversees the nondestructive testing and inspection (NDT/NDI)

procedures,

‘The manager of reliability is responsible for conducting the organization's reli-

ability program and ensuring that any problem areas are promptly addressed.

This responsibility includes data collection and analysis, identification of pos-

sible problem areas (which are then addressed in detail by engineering), and

publication of the monthly reliability report.

100

Safety

Summary of Management Levels

Organizational Structure and the TPPM

Fundamentals of Maintenance

‘The safety organization is responsible for developing, implementing, and admin-

istering the safety- and health-related activities within the M&E organization.

‘The safety manager is also responsible for handling all reports and claims

regarding M&E safety issues.

For all of the above organizations, the respective directors, managers, and

supervisors are also responsible for the more mundane activities that are nec-

essary for any smoothly operating organization. Those activities include the han-

dling of administrative and personnel duties; the budgeting and planning

requirements for their respective organizations (both long and short term); and

the necessary interactions with some or all of the other organizations, includ-

ing those outside of M&E, through a plethora of meetings, letters, documents,

memos, bull sessions, and chance meetings in the hallway.

‘The maintenance management organization discussed here is based on the con-

ventional approach where we group similar activities and provide a structure

within which all can work. It does not, however, subscribe to the “chain of com-

mand” philosophy where each hierarchical level has dominion over the lower

tiers. Rather it is meant to encourage the more modern approach of “cross-func-

tional coordination.”

This maintenance management structure can be classified as a system (see

Appendix A). Figure 7-1 represents a collection of structural and procedural com-

ponents designed to work together efficiently to perform the maintenance man-

agement function. As with any system, the theoretical design may differ from

what we actually attain when the plan is implemented in the real world. That

is, even management systems contain some entropy, some imperfection, both

natural and manufactured (see Chap. 1). Thus, it is important to understand

management's dual role in setting up and running an organization. Management

personnel have responsibilities similar to those of systems engineers: they must

develop a workable system and they must strive for a minimum amount of

imperfection (entropy) within that system. Management personnel also have

responsibilities similar to those of system mechanics: their ongoing job is

combat the natural increase in entropy that their system will doubtless unders

over time.

‘A manager is, in a sense, similar to an airplane pilot. In the early days

flying, it was a vigorous effort for the pilot to fly the aireraft. In the Wright broth

ers’first airplane, the operator laid down on his stomach and operated the nee

essary controls with his hands, his feet, and his hips. Later models allowed

to sit upright. For many years the pilot flew the airplane by “feel.” The vehi

was an extension of the pilot; the pilot and his or her aircraft were one unit; t

‘The Maintenance and Engineering Organization 101

flew together. In today’s modern aircraft, the pilot has the benefit of various com-

munication, navigation, and control systems which almost fly the airplane unas-

sisted. The pilot, then, after setting everything in working order, “sits back and

manages the flight.”

This does not mean that a pilot is less important and no longer needs rigor-

ous training. On the contrary, he or she must know as much as—actually more

than—any earlier pilot had to know. When something goes wrong, or does not

go as well as planned, the pilot must know instantly what to do, how to take

over from the automatic systems and fly the aircraft manually.

Management of maintenance and other technical activities is a similar effort

for those managers confined to the ground. In our typical management structure,

we have identified the organization necessary to carry out the M&E functions.

Management has determined this structure based on the rules stated earlier:

grouping of like functions, span of control, and separation of monitors from those

monitored. Further establishment of M&E operations is spelled out in detail in

the airline technical policies and procedures manual (TPPM) which is meticulously

developed by management at the beginning of operations to ensure smooth, cross-

functional coordination among the M&E units and to accomplish the stated goals

and objectives of the organization. Once the M&E organization and its operational

policies and procedures are established, and the hired personnel are trained on

those elements, management can then “sit back and manage the operation.”

Variations from the Typical Organization

It is obvious that the above organizational structure will not work for all com-

mercial operators. Airlines smaller than our “typical” airline, as well as those

which are much larger, cannot operate efficiently under this arrangement.

‘There must be variations in this structure to accommodate the differences.

‘These are discussed next.

Small airlines

Small airlines may not be able to organize in the manner shown in Fig. 7-1 for

two reasons. One, they may not have enough personnel to populate all these posi-

tions; and two, they may not have enough work to keep all, or some, of these

people occupied full time. It is obvious, then, that the management structure

must be altered. This can be done in several ways.

First of all, we must state that all of the activities identified in the typical orga-

nizational chart must be addressed to some extent in any airline. All of these

functions are necessary for efficient operation. However, due to size and per-

sonnel limitations, one individual or one section may be asked to perform more

‘than one of these functions. For example, quality control functions might be

assigned to personnel in the work centers. Mechanics and technicians would per-

form the inspection work as needed as an adjunct to their regular duties in main-

tenance. These QC inspectors, however, would be supervised by the quality

102 Fundamentals of Maintenance

assurance organization (or QA person) regarding these inspection activities.

More on this will be discussed in Chaps. 16 and 17.

Reliability and engineering functions might be combined in smaller airlines,

also, Technical publications, training, and even production planning and con-

trol may be combined with engineering to utilize available skills. Line and

hangar maintenance functions may be separate organizations but utilize many

of the same personnel. The two functions may also be combined as one main-

tenance organization.

Large airlines

For the larger airlines, especially those with more than one maintenance base, an

organizational structure different from Fig. 7-1 will be necessary. There will be

need for a hangar maintenance organization at each base where that type of work:

is done. For instance, MNO airlines may do hangar maintenance on their 757s at

Denver and on their A310s at Kansas City. One hangar maintenance organization

at the home base (wherever that may be) would not be adequate. It may be nec-

essary, though, to have a corporate-level manager responsible for both units, as

well as separate managers at each site. The same would apply to production plan-

ning and control and certain support shops for this arrangement. Again, it should

be emphasized that it is important to have the functions listed in our “typical” struc-

ture addressed no matter how the airline is actually organized.

Full versus partial organizational structure

It should also be pointed out that this “typical” airline structure is not adequate

for an airline that does not perform all the functions listed in Fig. 7-1. Many

small airlines, and some larger ones, do not do their own hangar maintenance

and, therefore, do not need the hangar maintenance organization. The same is

true for those airlines that outsource their shop maintenance in one or more

areas (avionics, hydraulics, etc.). But even if certain functions are not performed.

by the airline itself, these functions must be accomplished to properly maintain

the equipment. The airline must designate someone in the M&E organization

to be responsible for these functions, to see to their completion, and to coordi-

nate these actions with other aitline activities. These and other variations will

be discussed in the appropriate chapters later in the book.

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Teoría de Materiales CompuestosDocument3 pagesTeoría de Materiales CompuestosMariano BrionesNo ratings yet

- Tailfin RudderDocument1 pageTailfin RudderMariano BrionesNo ratings yet

- Cosa-0614 Manual de Capacitación de SobrecargosDocument10 pagesCosa-0614 Manual de Capacitación de SobrecargosMariano BrionesNo ratings yet

- AESA EspañaDocument16 pagesAESA EspañaMariano BrionesNo ratings yet