Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effets Osteopathie Sur Plagiocephalie

Effets Osteopathie Sur Plagiocephalie

Uploaded by

LaidetOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effets Osteopathie Sur Plagiocephalie

Effets Osteopathie Sur Plagiocephalie

Uploaded by

LaidetCopyright:

Available Formats

Infantile postural In infancy, persistent asymmetry of spontaneous movements,

muscle tone, automatic responses, and reflexes may be a clue

to hemiplegia, cervical plexus injury, disturbances of spine seg-

asymmetry and mentation, or other neuromuscular disorders (Brett 1991,

Cioni et al. 2000, Vojta 2000). However, the cause is unknown

osteopathic treatment: in most patients and these cases are termed idiopathic (James

1975, Canale 1982). Depending on the most pronounced fea-

a randomized ture of this disease, terms like congenital torticollis, idiopathic

infantile scoliosis, or deformational plagiocephaly have been

used (Lloyds-Roberts and Pilcher 1965, James 1975, Mau 1979,

therapeutic trial Binder et al. 1987, Rosegger and Steinwendner 1992, Cheng

and Au 1994, Walsh and Morrissy 1998). Addressing the entire

symptom complex, terms such as positional preference

(Boere-Boonekamp and van der Linden-Kuiper 2001, Cheng

Heike Philippi* MD, Department of Paediatric Neurology, and Au 1994), moulded baby syndrome (Lloyds-Roberts and

University Children’s Hospital, Heidelberg; Pilcher 1965), seventh syndrome (Mau 1979), or turned head-

Andreas Faldum PhD, Institute for Medical Biostatistics, adducted hip-truncal curvature syndrome (Hamanishi and

Epidemiology and Informatics, Johannes Gutenberg- Tanaka 1994) have been proposed. Focussing on the function-

University; al restrictions of this symptom complex we introduce the term

Angela Schleupen DO; infantile postural asymmetry, which is defined as the coinci-

Bianka Pabst DO, Center of Osteopathy; dence of cervical rotation deficit and trunk convexity for which

Tatjana Jung; a measurement scale was devised (Philippi et al. 2004).

Holger Bergmann; Endogenous and exogenous factors are thought to cause

Imke Bieber MD; the asymmetry complex. Exogenous factors are intrauterine

Christine Kaemmerer MD, University Children’s Hospital, and/or postnatal constraint and birth injuries (Lloyds-Roberts

Johannes Gutenberg-University; and Pilcher 1965, Wynne-Davies 1975, Rosegger and Stein-

Piet Dijs DO, Center of Osteopathy; wendner 1992, Cheng and Au 1994). Genetic disposition, as

Bernd Reitter MD, University Children’s Hospital, Johannes shown by a family history of scoliosis, rapid growth, reduced

Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany. muscle tone, and reduced motor activity, contributes to the

development of postural asymmetry (Wynne-Davies 1975, Mau

*Correspondence to first author at Department of 1979, McMaster 1983). Contractures, followed by asymmetric

Paediatric Neurology, University Children’s Hospital, Im structural growth and weight-bearing deformities, are second-

Neuenheimer Feld 150, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. ary morphological abnormalities that may produce a vicious

E-mail: Heike.Philippi@med.uni-heidelberg.de circle (Wynne-Davies 1975, Mau 1979).

Although the prognosis of the infantile asymmetry com-

plex is thought to be good in most cases, retrospective stud-

ies have shown persistent or progressive scoliosis in 10–50%

of all patients (Lloyds-Roberts and Pilcher 1965, Ferreira et

The aim of this study was to assess the therapeutic efficacy of al. 1972, James 1975, Wynne-Davies 1975, Thompson 1980,

osteopathic treatment in infants with postural asymmetry. A Canale et al. 1982, McMaster 1983, Binder et al. 1987). A

randomized clinical trial of efficacy with blinded videoscoring recent 2-year prospective study showed that in 25% of

was performed. Sixty-one infants with postural asymmetry asymmetric infants asymmetric features will persist (Boere-

aged 6 to 12 weeks (mean 9wks) were recruited. Thirty-two Boonekamp and van der Linden-Kuiper 2001). This may be

infants (18 males, 14 females) with a gestational age of at the reason for a growing number of therapeutic attempts

least 36 weeks were found to be eligible and randomly including physiotherapy, manual therapy, and osteopathy.

assigned to the intervention groups, 16 receiving osteopathic None of these interventions has been evaluated in con-

treatment and 16 sham therapy. After a treatment period of 4 trolled studies.

weeks the outcome was measured using a standardized scale Based on a positive episodic clinical experience we decided

(4–24 points). With sham therapy, five infants improved (at to evaluate osteopathic treatment in a blinded, randomized

least 3 points), eight infants were unchanged (within 3 trial. Osteopathy is less invasive than other interventions, safe

points), and three infants deteriorated (not more than –3 and, being performed by the osteopath, independent of the

points); the mean improvement was 1.2 points (SD 3.5). In parents’ compliance (Sutherland 1990, Magoun 2001). Fine

the osteopathic group, 13 infants improved and three manipulative palpation techniques, which are individually

remained unchanged; the mean improvement was 5.9 points adapted to tissue quality, are the hallmark of this alternative

(SD 3.8). The difference was significant (p=0.001). We form of therapy. It is believed to ‘maintain or restore the circu-

conclude that osteopathic treatment in the first months of life lation of body fluids’. The manipulation is nearly invisible from

improves the degree of asymmetry in infants with postural the outside and allows for blinding the intervention in the

asymmetry. presence of the parents. The outcome was measured using a

standardized video-based asymmetry scale (Philippi et al.

2004). Results are reported following the recommendations

of the revised Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

(CONSORT) statement (Altman et al. 2001).

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2006, 48: 5–9 5

Method maximal asymmetry. Statistical analysis indicated good relia-

SETTING AND PATIENTS bility and consistency of the testing method, with an intra-

The trial was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the University class correlation coefficient of 91.5% (Cronbach alpha 0.84).

Children’s Hospital and the treatment was administered at Video tracings obtained at baseline and one week after the

the Center of Osteopathy, Mainz, Germany. The enrolment last intervention were compared.

period was from March 2002 to December 2002; the last fol- Secondary objectives were factors that may affect treatment

low-up was in January 2003. outcome. They included growth, age, and sex, which were

Infants aged 6 to 12 weeks (postterm age) with a diagnosis derived from charts. Infantile position awake and asleep, time

of postural asymmetry were referred from 19 paediatric prac- for carrying or ‘kangarooing’, and putting the infant in a car

tices in Mainz. A baseline full medical history was obtained, seat were recorded by the parents on a standardized ques-

and the infants were neurologically and physically examined tionnaire using a 4-point scale (less than 1h a week; 2–6h a

by a paediatric neurologist and a physiotherapist to establish week; 1–4h a day; more than 5h a day). At each visit the par-

the degree of asymmetry (see Objectives, observation tech- ents were asked to report any illness of the infant on a free

niques, and outcomes). Exclusion criteria were: (1) asymme- questionnaire.

try score below 12 points; (2) significant underlying disease; A further secondary objective was the evaluation of the

(3) gestational age below 36 weeks; (4) parents not familiar effects of osteopathic treatment on vegetative parameters of

with the German language; (5) any other treatment for asym- the infants. At baseline and after each intervention the par-

metry in the past or at present except for handling; (6) pre- ents were asked to complete a standardized questionnaire

dominant oblique body position masking the trunk curvature; quantifying changes in vomiting, sleeping, drinking, mood,

and (7) lack of parental informed consent. excitability, stool frequency, and crying on a 3-point scale

The trial was approved by the ethics board of the Johannes (more/better, same, less/worse, or don’t know). To identify

Gutenberg-University, Mainz, and all parents provided writ- excessive crying, which is supposed to be more prevalent in

ten informed consent. asymmetric infants, the parents had to complete the stan-

dardized questionnaire according to Wurmser et al. (2001).

TREATMENT

Infants with asymmetry were randomized to receive either RANDOMIZATION AND BLINDING

osteopathic treatment or sham therapy. Infants in both At the baseline visit, the trial was explained in detail and writ-

groups were treated once a week for 45–60 minutes over 1 ten informed consent was obtained from the parents within

month. After each intervention the parents of all infants were the next three days. Eligible infants were randomly assigned to

instructed in handling their infant, based on the Bobath con- the treatment groups. Block randomization was used to

cept (Lommel-Kleinert 1999, von Aufschnaiter 1999). achieve a balanced parallel group design stratified for two age

For the osteopathic treatment the infants were placed on a groups (6–8 wks and 9–12 wks). The assignments were pre-

table, with the parents sitting beside them. At each visit the sented in sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes to the

osteopathic technique, and the area it was applied to, was study coordinator who scheduled the intervention appoint-

adapted depending on the diagnostic palpation of the osteo- ments by telephone and informed the osteopath about the

path who assessed and treated position, tissue quality, mobility, infant’s group assignment.

and relation to the environment of the skull, sacrum, iliac and Parents, video scorers, and the physiotherapists and

coccygeal bones, thorax, sternum, diaphragm, and abdomen. physicians performing the baseline and final examinations

The specific procedures were recorded by the osteopath. For were blinded to the treatment assignment for the duration of

instance, so-called primary respiration and the cranial rhyth- the trial. Osteopaths, statistician, and study coordinator

mic impulse, thought to be very fine autonomous rhythmic were unblinded.

changes of tissue quality, were used to disengage fixations of

adjoining structures (Sutherland 1990, Magoun 2001). The STATISTICAL ANALYSIS AND STOPPING RULES

osteopathic treatment was administered by osteopaths who For testing the null hypothesis the mean of the total score of

were experienced in the treatment of young infants. a patient rated by three independent observers given at the

For the sham treatment, the osteopaths placed their hands outcome recording was subtracted from the respective mean

on the infants in comparable positions without treating them. total score at the baseline recording. This averaged total

For the parents the difference between sham therapy and score difference (TSC) was the assessment criterion for the

osteopathic treatment was unrecognizable. primary objective of the trial. The interobserver reliability of

TSC was assessed using intraclass correlation.

OBJECTIVES , OBSERVATION TECHNIQUES , AND OUTCOMES The one-sided null hypothesis that the TSC is not larger after

The primary objective of the current trial was to test the osteopathic therapy than after sham therapy was checked on a

hypothesis that osteopathic treatment does not improve the significance level of α=0.025 by using an adaptive design with

degree of asymmetry in infants with infantile postural asym- two stages and independent-samples t-tests. The significance

metry (null hypothesis). The degree of asymmetry was limit for the p value of the first stage was 0.016 to reject the null

assessed using standardized video-based measurements, as hypothesis and 0.15 to stop the trial for lack of benefit. The

reported elsewhere (Philippi et al. 2004). In brief, trunk con- adaptive design was chosen according to a design of Bauer and

vexity and cervical rotation deficit as reactive movements to Köhne (1994), which was modified by a slope parameter. The

an orienting head turn in the prone and supine positions principle of modification by slope parameters will be given in a

were assessed by three independent, trained, and blinded forthcoming paper by the authors. Consequently, the null

observers using a 6-point scale for each item. A total score of hypothesis had to be rejected after the second stage if the p

4 points represents no symmetry and a score of 24 points value of the second stage was smaller than or equal to 1.366

6 Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2006, 48: 5–9

divided by the sum of the p value of the first stage and 20.985. and non-responders in the treatment group we tried to identify

The primary outcome was evaluated by intention-to-treat predictive outcome factors. Growth, age, sex, car seat sitting,

analysis. Rules for the analysis of the primary outcome were

established before starting the study and documented in the Table I: Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

proposal submitted to the ethical board.

Possible confounders on TSC were regarded as explo- Characteristics Treatment Control Relation to

rative, and the p values of the corresponding tests are pre- group group outcome

sented for descriptive reasons only. The impact of growth (n=16) (n=16)

and age on TSC was evaluated by Pearson’s rank correlation Mean (SD) age, wks 9 (2) 9 (2) No (r=0.05)a

coefficient. The influence of sex, infantile position, parental Sex, male/female, n 9/7 9/7 No (p=0.64)b

carrying, car seat sitting, and infection on TSC, as well as the Mean (SD) growth, cm 3.9 (1.7) 3.2 (1.2) No (r=0.06)a

correlation between TCS and vegetative parameters, were Posture awake, n No (p=0.35)b

examined by independent-samples t-tests. All positions 7 5

No prone position 9 11

SAMPLE SIZE Posture asleep, n Not testedc

Following the adaptive design described above, 16 patients Supine 11 12

had to be recruited for each group to achieve a power of 80% Supine, side 4 4

Prone 1 0

at the first stage if the TSC after osteopathic treatment was 4

Parental carrying, n Not testedc

points larger than the TSC after sham therapy and the SD was <1h/week 1 0

3.7 in both groups. The underlying assumptions for the 2–6h/week 1 1

power calculation were chosen in accordance with the expe- 1–4h/day 11 14

rience of a pilot study of 12 asymmetric infants aged 7–12 >5h/day 3 1

weeks (mean 10wks), who were scored before and after an Car seat sitting, n No (p=0.23)b

interval of 4 weeks without any treatment. Asymmetry in <1h/week 7 2

these infants showed a mean deterioration of 1 point (SD 2–6 h/week 9 12

3.7). Using an adaptive design the number of patients for the >1h/day 0 2

second stage had not to be fixed beforehand. The power cal- Mode of birth, n Not testedc

Spontaneous delivery 12 6

culation for the stage had to be performed before starting the

Caesarean section 3 7

second stage if the p value of the first stage was between Vacuum delivery 0 3

0.016 and 0.15. All results of the first stage could have been Forceps delivery 1 0

used for these calculations. Fetal position at birth, n Not testedc

Cephalic presentation 14 12

Results Face presentation 1 1

Sixty-one infants were referred and assessed for eligibility. Of Breech presentation 1 3

those, 29 infants were rejected. Thirty-two infants were ran- Mean time of final fetal birth

domized and 16 infants were allocated to each study group position, wks 13 12 Not testedc

for the first-stage evaluation. There was no protocol viola- (Range) (1–28) (15–28)

Mean first fetal movements, gest. wks 21 21 Not testedc

tion. The osteopathic-treatment group and the sham-treatment

(Range) (16–28) (15–28)

group were similar for demographic and clinical variables Fetal movement amountd, n Not testedc

(Table I). All infants of the treatment group and all but one Little 2 2

infant of the control group attended the four interventions. Moderate 4 4

One infant of the control group received only three interven- Much 10 10

tions, which was still in accordance with the study protocol. Oxytocin infusion during birth, n 10 8 Not testedc

Final video documentation 4 weeks after the last interven- Peridural anaesthesia, n 5 6 Not testedc

tion was obtained for all infants, and all their videos were Parity, n Not testedc

subsequently analyzed. 1 9 12

Mean changes in the asymmetry score from baseline to the 2 6 3

3 0 1

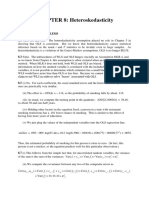

final visit are shown in Figures 1 and 2. In the control group the

4 1 0

mean improvement was 1.2 points (SD 3.5) from 14.2 points Twin birth, n 2 1 Not testedc

(SD 2.0) to 13 points (SD 2.8), and in the treatment group 5.9 Mean birthweight, g 3390 3330 Not testedc

points (SD 3.8) from 15.4 (SD 2.7) to 9.5 (SD 3.1). The mean (range) (2415– (2720–

TSC between both groups was 4.7 points (95% confidence 4300) 4250)

interval [CI] 2.0 to 7.3) with p=0.001 (significance limit Excessive cryinge, n 4 6 Not testedc

p<0.017), implying that the trial was finished after the first- Illnesses, n No (p=0.57)b

stage evaluation. The intraclass correlation coefficient was Common cold 5 5

81% (95% CI 71 to 91%), reflecting a good interobserver relia- Diarrhoea 0 2

bility. In the control group, five infants improved (at least 3 Mean asymmetry score

points (SD) 15 (3) 14 (3) Not tested

points), eight infants were unchanged (within 3 points), and

three infants deteriorated (not more than –3 points). In the aPearson’s correlation; bt-test for independent variables; cSample

treatment group 13 infants improved and three remained size did not allow statistical analysis; dSubjective judgement of the

unchanged. women; eAt least 3 hours per day for at least 3 days per week, for at

To explain spontaneous improvement in the control group least 3 weeks (Wurmser et al. 2001). gest., gestation.

Infantile Postural Asymmetry and Osteopathic Treatment Heike Philippi et al. 7

parental carrying, position awake and asleep, and infections The relative short intervention period of 4 weeks was cho-

were not predictive for outcome (Table I). sen because validation of the asymmetry scale was limited to

Changes in the vegetative parameters were similar in both this age group. The high variability of inter- and intraindivid-

groups: vomiting (p=0.06), sleeping (p=0.36), drinking ual maturation and self-regulating processes currently pre-

(p=0.62), mood (p=0.58), excitability (p=0.47), stool fre- cludes evaluating the extent of spontaneous improvement.

quency (p=0.2), and crying (p=0.42). Ten out of 32 infants, six However, the results of a 2-year follow-up study of 623 infants

from the control group and four from the treatment group, with asymmetry demonstrated a persistence of asymmetric

showed excessive crying as defined by Wurmser et al. (2001). features in about 25% of the children (Boere-Boonekamp and

All parents were satisfied with the study. At least two of the van der Linden-Kuiper 2001). Our patients are currently fol-

seven vegetative symptoms aggravated for 2 days after the inter- lowed up using a standardized protocol, although their analy-

ventions in six patients of the control group and in four sis will be complicated by variable individual treatment regimes

patients of the treatment group. Otherwise no adverse effects after the end of the study.

were seen. As the analysis of our data failed to identify any reliable

predictor for outcome, the question of which asymmetric

Discussion infant has to be treated cannot be answered. During the

The results of our therapeutic trial render first evidence that spontaneous course (pilot study for sample size calculation)

osteopathic treatment in the first months of life significantly we have seen both spontaneous improvement and deteriora-

improves the degree of asymmetry in infants with postural tion. Consequently, the only way of avoiding over- or under-

asymmetry. Blinding the intervention and using a standard- treatment is to watch closely the development of the asymmetric

ized measuring scale asserted the objectivity of this result. infant by using the asymmetry scale. During the observation

Sample size calculation and an adaptive study design allowed period, handling recommendations may be beneficial as indi-

early completion of the study with an overall size of 32 cated by a mean improvement of 1.2 points in the control

infants, suggesting a strong treatment effect. The study ques- group versus a mean deterioration of 1 point in the preceding

tion was formulated as one-sided to avoid directional con- spontaneous course group. Admittedly, accepting a waiting

flicts between both adaptive stages. Moreover, we planned to period conflicts with empirical knowledge that with decreas-

recommend osteopathic treatment only if there was clear ing tissue smoothness, therapeutic efficacy may decrease.

superiority of this therapy. Therefore, and for ethical rea- Not until recently have asymmetric features in infancy

sons, we did not plan the trial to be continued to demon- been studied in a standardized and prospective way (Cioni

strate that osteopathic treatment may be harmful. However, et al. 2000, Boere-Boonekamp and van der Linden-Kuiper

additional studies with a larger sample are required to evalu- 2001, Philippi et al. 2004). However, different aspects have

ate the consistency of the effect of osteopathic treatment on been considered and terminology is preliminary. This may

infantile postural asymmetry. be a potential source of confusion. Cioni’s asymmetry scale

15

24

Before After Before After

20 10

Asymmetry score (points)

TSC (points)

16 5

12 0

8 –5

4 –10

Control group Treatment group Control group Treatment group

Figure 1: Total score before and after intervention in Figure 2: Total score difference (TSC) in treatment and

treatment and control groups. Results are presented by box- control groups presented as box-and-whisker plots. A

and-whisker plots. Horizontal line in middle of a box shows positive TSC represents an improvement, a negative TSC a

mean. Edges of a box mark 25th and 75th centiles. Whiskers deterioration.

show range of values that fall within 1.5 box-lengths. Values

more than 1.5 box-lengths from 25th or 75th centiles are

marked by a circle.

8 Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2006, 48: 5–9

evaluates asymmetric general movements and serves for Bauer P, Köhne K. (1994) Evaluation of experiments with adaptive

early identification of hemiplegia. Boere-Boonekamp and our interim analyses. Biometrics 50: 1029–1041.

study group investigated the same condition: the entire Binder H, Eng GD, Gaiser JF, Koch B. (1987) Congenital muscular

torticollis: results of conservative management with long-term

infantile and idiopathic asymmetry complex (see Intro- follow-up in 85 cases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 68: 222–225.

duction) from different perspectives. The Boere-Boonkamp Boere-Boonekamp MM, van der Linden-Kuiper AT. (2001)

group studied the course in infants with positional prefer- Positional preference: prevalence in infants and follow-up after

ence, which was defined as a head rotation preference to one two years. Pediatrics 107: 339–343.

Brett EM, editor. (1991) Paediatric Neurology. New York: Churchill

side and head rotation restriction to the contralateral side in Livingstone.

the supine position. Our study group focused on head and Canale ST, Griffin DW, Hubbard CN. (1982) Congenital muscular

spinal movement restrictions in the supine and prone posi- torticollis. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 64: 810–816.

tions. However, the data of both study groups highlight that Cheng JC, Au AW. (1994) Infantile torticollis: a review of 624 cases.

for evaluation of the asymmetric infant and its sequels (per- J Pediatr Orthop 14: 802–808.

Cioni G, Bos AF, Einspieler C, Ferrari F, Martijn A, Paolicelli PB,

sistent scoliosis, restricted head movements, asymmetric gait Rapisardi G, Roversi MF, Prechtl HFR. (2000) Early neurological

disturbances, facial scoliosis with temporomandibular joint signs in preterm infants with unilateral intraparenchymal

displacement and/or functional lateralities), the broad clini- echodensity. Neuropediatr 31: 240–251.

cal spectrum including functional aspects has to be consid- Ferreira JH, de Janeiro R, James JIP. (1972) Progressive and resolving

infantile idiopathic scoliosis: the differential diagnosis. J Bone

ered rather than prematurely categorizing an infant as having Joint Surg. Br 54: 648–655.

torticollis, scoliosis, or plagiocephaly only. Hamanishi C, Tanaka S. (1994) Turned head-adducted hip-truncal

Physiotherapy and manual intervention are used in many curvature syndrome. Arch Dis Child 70: 515–519.

infants including those with postural asymmetry, but there James JIP. (1975) The management of infants with scoliosis. J Bone

have been few attempts to prove their effectiveness. Although Joint Surg. Br 57: 422–429.

Lloyds-Roberts GC, Pilcher MF. (1965) Structural idiopathic

research in this young age group is difficult because of matura- scoliosis in infancy: a study of the natural history of 100 patients.

tion effects, the protocol of our asymmetry model opens the J Bone Joint Surg. Br 47: 520–523.

opportunity for similar studies of other therapeutic concepts. Lommel-Kleinert E, editor. (1999) Handling und Behandlung auf

dem Schoß. In: Anlehnung an das Bobath-Konzept. München:

Pflaum. (In German)

Conclusions Magoun HI, editor. (2001) Osteopathie in der Schädelsphäre.

Our data suggest that osteopathic treatment in the first Montreal: Édition Spirales. (In German)

months of life is beneficial for infants with idiopathic asym- Mau H. (1979) Zur Ätiopathogenese von Skoliose, Hüftdysplasie

metry, and that rehabilitation methods can be evaluated in und Schiefhals im Säuglingsalter. Z Orthop 117: 784–789.

this young age group. (In German)

McMaster MJ. (1983) Infantile idiopathic scoliosis: can it be

prevented? J Bone Joint Surg. Br 65: 612–617.

DOI: 10.1017/S001216220600003X Philippi H, Faldum A, Bergmann H, Jung T, Pabst B, Schleupen A.

(2004) Idiopathic infantile asymmetry, proposal of a

Accepted for publication 23rd December 2004. measurement scale. Early Hum Dev 80: 79–90.

Rosegger H, Steinwendner G. (1992) Transverse fetal position

syndrome – a combination of congenital skeletal deformities in

Acknowledgements the newborn infant. Paediatr Padol 127: 125–127.

We acknowledge the continued support and criticism of Juergen Sutherland WG, editor. (1990) Teaching in the Science of

Spranger, former head of the University Children’s Hospital, Mainz, Osteopathy. Texas: Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation.

Germany. We are grateful to Miriam Auerbach, Andrea Blum, Gisela Thompson SK. (1980) Prognosis in infantile idiopathic scoliosis.

Foerster, Daniela Gross, and Sabine Nennmann for their assistance J Bone Joint Surg. Br 62: 151–154.

with therapy. We also thank Ruediger von Kries of the Institute for Vojta V, editor. (2000) Die zerebralen Bewegungstörungen im

Social Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University of Munich, Säuglingsalter. Stuttgart: Hippokrates. (In German)

Germany, for providing the standardized questionnaire for von Aufschnaiter D. (1999) Entwicklung und Entwicklungsdiagnostik.

excessive crying. This study was supported by the MAIFOR Fund of In: Hartmannsgruber R, Wenzel D, editors. Physiotherapie

the Johannes Gutenberg-University. Pädiatrie volume 12. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme. p 5–25.

(In German)

Walsh JJ, Morrissy RT. (1998) Torticollis and hip dislocation.

J Pediatr Orthop 18: 219–221.

Wurmser H, Laubereau B, Hermann M, Papousek M, von Kries R.

References (2001) Excessive infant crying: often not confined to the first 3

Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elboume D, months of age. Early Hum Dev 64: 1–6.

Gotzsche PC, Lang T, for the CONSORT Group. (2001) The Wynne-Davies R. (1975) Infantile idiopathic scoliosis: causative

revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: factors, particularly in the first six months of life. J Bone Joint

explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134: 663–694. Surg. Br 57: 138–141.

Infantile Postural Asymmetry and Osteopathic Treatment Heike Philippi et al. 9

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Conflict-Management Style SurveyDocument5 pagesConflict-Management Style SurveyFelicia Cristina CotrauNo ratings yet

- Employee Promotion Proposal Form - MominDocument2 pagesEmployee Promotion Proposal Form - MominTanvir Raihan TannaNo ratings yet

- Ap Stats CH 6 TestDocument6 pagesAp Stats CH 6 Testapi-2535798530% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Studio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFDocument214 pagesStudio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFMohammad J Haddad88% (8)

- Handbook of Polypropylene and Polypropylene Composites Revised and Expanded Plastics EngineeringDocument5 pagesHandbook of Polypropylene and Polypropylene Composites Revised and Expanded Plastics EngineeringNouman AliNo ratings yet

- October 2016 Paper 1 MSDocument10 pagesOctober 2016 Paper 1 MSAryaveer Kumar100% (1)

- Rocinante 36 Marengo 32 Car No. Car No. Mileage (KM/LTR) Top Speed (KM/HR) Mileage (KM/LTR) Top Speed (KM/HR)Document14 pagesRocinante 36 Marengo 32 Car No. Car No. Mileage (KM/LTR) Top Speed (KM/HR) Mileage (KM/LTR) Top Speed (KM/HR)Prateesh DeepankarNo ratings yet

- Amada Laser CuttingDocument8 pagesAmada Laser CuttingMahmud MaherNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Loaded Albumin Nanoparticles by Coacervation: Implications in Drug DeliveryDocument10 pagesAspirin Loaded Albumin Nanoparticles by Coacervation: Implications in Drug DeliveryafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- E3 FullDocument2 pagesE3 FullafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Effect of Aspirin On Disability-Free Survival in The Healthy ElderlyDocument10 pagesEffect of Aspirin On Disability-Free Survival in The Healthy ElderlyafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Infeccion VHSDocument17 pagesInfeccion VHSafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Brjclinpharm00184 0136Document6 pagesBrjclinpharm00184 0136afandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0165572817305052Document9 pagesPi Is 0165572817305052afandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- 01 Res 51 3 385Document6 pages01 Res 51 3 385afandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Strain KOS Carries A Defective US9 and A Mutated US8A GeneDocument6 pagesHerpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Strain KOS Carries A Defective US9 and A Mutated US8A GeneafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Hydrochlorothiazide: Captopril and Atenolol Combined With in Essential HypertensionDocument5 pagesHydrochlorothiazide: Captopril and Atenolol Combined With in Essential HypertensionafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Ancient Recombination Events Between Human Herpes Simplex VirusesDocument9 pagesAncient Recombination Events Between Human Herpes Simplex VirusesafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Lidocaine's Negative Inotropic and Antiarrhythmic ActionsDocument13 pagesLidocaine's Negative Inotropic and Antiarrhythmic ActionsafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0885392405003271Document2 pagesPi Is 0885392405003271afandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacology Antiarrhythymic: The of Lidocaine DrugDocument14 pagesClinical Pharmacology Antiarrhythymic: The of Lidocaine DrugafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Ibvt07i11p838 PDFDocument4 pagesIbvt07i11p838 PDFafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Screening Blood Donors at Risk For Malaria: Reply To Hänscheid Et AlDocument2 pagesScreening Blood Donors at Risk For Malaria: Reply To Hänscheid Et AlafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2012 Bingen 2540.fullDocument2 pagesJournal of Clinical Microbiology 2012 Bingen 2540.fullafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Quantification of Menstrual Blood Loss: The Menorrhagia Research GroupDocument5 pagesQuantification of Menstrual Blood Loss: The Menorrhagia Research GroupafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- BPN Datangi MalaysiaDocument62 pagesBPN Datangi MalaysiaafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- Osteo PDFDocument119 pagesOsteo PDFafandianddonkeyNo ratings yet

- ISO9000 Is It Worth ItDocument42 pagesISO9000 Is It Worth ItCarlos De Peña EvertszNo ratings yet

- Answers For /Ʒ/ and /Ʃ/ ExercisesDocument1 pageAnswers For /Ʒ/ and /Ʃ/ ExercisesLuis F VargasNo ratings yet

- The Forms and Functions of Impulsive Actions: Implications For Behavioral Assessment and TherapyDocument19 pagesThe Forms and Functions of Impulsive Actions: Implications For Behavioral Assessment and TherapyGabriel Mercado InsignaresNo ratings yet

- Sample 15Document2 pagesSample 15Schedar May Jumonong SantillanNo ratings yet

- 2yc Coc QerDocument6 pages2yc Coc QerMiguel HernandezNo ratings yet

- Training Manual A 319/320/321: ATA 34 NavigationDocument78 pagesTraining Manual A 319/320/321: ATA 34 NavigationhatollintNo ratings yet

- Ground Penetrating RadarDocument72 pagesGround Penetrating RadarNag Bhushan100% (1)

- Google Android: Mobile ComputingDocument23 pagesGoogle Android: Mobile Computingsaah007No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 8 End of ChapterDocument2 pagesCHAPTER 8 End of Chapterbobhamilton3489No ratings yet

- 03u 3 PDFDocument20 pages03u 3 PDFjaiNo ratings yet

- AI Q1. Attempt Any FourDocument7 pagesAI Q1. Attempt Any FourziddirazanNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Gerd Dengan DepresiDocument8 pagesHubungan Gerd Dengan DepresiDella Elvina RoeslandNo ratings yet

- 01443570210414329Document108 pages01443570210414329Sajid Mohy Ul DinNo ratings yet

- Error Cpanel1Document7 pagesError Cpanel1mosharaflinkNo ratings yet

- 2) S1-S3 Learning Schedule (Feb 17 To Mar 13)Document4 pages2) S1-S3 Learning Schedule (Feb 17 To Mar 13)Ben FungNo ratings yet

- Cartographies of Experience Rethinking The Method of Liberation TheologyDocument25 pagesCartographies of Experience Rethinking The Method of Liberation TheologypatricioafNo ratings yet

- Sight Word List 1Document2 pagesSight Word List 1DawnNo ratings yet

- Part A Unit 1 Communication SkillsDocument6 pagesPart A Unit 1 Communication Skillssajanaka161No ratings yet

- Jawaban Network Fundamental CybraryDocument3 pagesJawaban Network Fundamental CybraryCerberus XNo ratings yet

- Balancing Tip # 105 C D International, IncDocument3 pagesBalancing Tip # 105 C D International, IncAnonymous PVXBGg9TNo ratings yet

- Linux CommandsDocument7 pagesLinux CommandsBharath ThambiNo ratings yet

- HTTP://WWW Bized Co UkDocument16 pagesHTTP://WWW Bized Co UkBMAARTINo ratings yet