Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Childhood Trauma and Dissociat

Uploaded by

EnaraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Childhood Trauma and Dissociat

Uploaded by

EnaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Paper

Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 Received: August 12, 2008

Accepted after revision: April 23, 2009

DOI: 10.1159/000255961

Published online: November 6, 2009

Childhood Trauma and Dissociation in

Schizophrenia

Vedat Sar a Okan Taycan b Nurullah Bolat c Mine Özmen b Alaattin Duran b

Erdinç Öztürk a Hayriye Ertem-Vehid d

a

Clinical Psychotherapy Unit and Dissociative Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, Istanbul Faculty of

Medicine, Departments of b Psychiatry and c Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine, and

d

Department of Family Health, Institute of Pediatrics, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

Key Words ported. Childhood trauma is related to concurrent dissocia-

Schizophrenia ⴢ Dissociation ⴢ Childhood trauma ⴢ tion among patients with schizophrenic disorder. A duality

Comorbidity ⴢ Psychosis model based on the interaction of 2 qualitatively distinct

psychopathologies and a dimensional approach are pro-

posed as possible explanations for the complex relation-

Abstract ship between these 2 psychopathologies and childhood

Background: This study is concerned with relationships be- trauma. Copyright © 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel

tween childhood trauma history, dissociative experiences,

and the clinical phenomenology of chronic schizophrenia.

Sampling and Methods: Seventy patients with a schizo-

phrenic disorder were evaluated using the Structured Clin- Introduction

ical Interview for DSM-IV, Dissociative Experiences Scale,

Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule, Positive and Dissociative disorders are increasingly considered as a

Negative Symptoms Scales, and Childhood Trauma Ques- chronic complex post-traumatic psychopathology closely

tionnaire. Results: Childhood trauma scores were correlated related to childhood abuse and/or neglect [1]. Subjects

with dissociation scale scores and dissociative symptom with dissociative disorders frequently report childhood

clusters, but not with core symptoms of the schizophrenic traumas, both in clinical settings [2] and in the general

disorder. Cluster analysis identified a subgroup of patients population [3]. Alongside clinical series [4, 5], the rela-

with high dissociation and childhood trauma history. The tionship between childhood trauma and dissociation has

dissociative subgroup was characterized by higher numbers been verified both in prospectively designed studies [6]

of general psychiatric comorbidities, secondary features of and using retrospective investigation of highly reliable

dissociative identity disorder, Schneiderian symptoms, so- forensic documents [7]. Recent studies document that pa-

matic complaints, and extrasensory perceptions. A signifi- tients with schizophrenia [8–11] or psychosis [12–14] also

cant majority of the dissociative subgroup fit the diagnostic report childhood traumas more frequently than controls.

criteria of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder concur- Ten out of eleven recent general population studies have

rently. Among childhood trauma types, only physical abuse found, even after controlling for other factors (including

and physical neglect predicted dissociation. Conclusions: A family history of psychosis), that child maltreatment is

trauma-related dissociative subtype of schizophrenia is sup- significantly related to psychosis [15]. Although consid-

© 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel Vedat Sar, MD

0254–4962/10/0431–0033$26.00/0 Istanbul Tip Fakultesi

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 Psikiyatri Klinigi

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: TR–34390 Capa Istanbul (Turkey)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/psp Tel. +90 212 260 1422, Fax +90 212 261 7004, E-Mail vsar@istanbul.edu.tr

eration of psychological trauma as a direct cause of a per- psychopathological distress, whereas the increase in dis-

vasive mental illness like schizophrenia is controversial sociation in this group of patients was considered as sec-

[16], a traumagenic neurodevelopmental model has been ondary to the increase in symptom load. In a third study,

proposed to explain a potential relationship [17]. trauma and dissociation were associated with severer

Patients with a schizophrenic disorder may come with symptoms of schizophrenia [29]. In particular, high dis-

concurrent psychiatric conditions, such as major depres- sociation was associated with an increase in symptom

sion, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or substance use load, whereas traumatic events fitting PTSD criterion A

disorder [18]. Although there are contradictory findings of DSM-IV and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

[19], dissociative symptoms [8, 9, 20, 21] and disorders had little or no such effect.

[10] have also been reported in patients with schizophre- Based on this accumulating evidence, the present

nia. Based on clinical phenomenology and childhood study was concerned with possible relationships between

trauma history, Ross proposed a dissociative subtype of childhood trauma, dissociative experiences, and the clin-

schizophrenia [22]. In accordance with claims for a direct ical phenomenology of chronic schizophrenia. While in-

relationship between schizophrenia and dissociation quiring into the characteristics of these associations, the

[23], he also proposed that non-dissociative schizophre- study also tried to determine if there was a trauma-re-

nia, the dissociative subtype of schizophrenia, schizo- lated dissociative subgroup among patients with schizo-

dissociative disorder, and dissociative identity disorder phrenic disorder. Beside correlational analyses between

(DID) constitute a spectrum. various scale scores, schizophrenic patients with high

There is convincing evidence that childhood trauma and low dissociation levels were compared on various

history has at least an impact on the clinical phenomenol- clinical measures, including general psychiatric comor-

ogy of schizophrenia. For instance, in 1 study, severity bidity and childhood trauma reports. As an examination

and frequency of childhood maltreatment were both pos- of the true subgroups derived from a combination of var-

itively correlated with hallucinations and delusions [24]. ious measures, patients were also classified by an inde-

Another study demonstrated that child abuse was related pendent cluster analysis directly.

to hallucinations (auditory and tactile ones in particular),

but not to delusions, thought disorder, or negative symp-

toms, which are known to be the more robust symptoms

Method

of schizophrenia [25]. Patients with schizophrenia not

only report childhood trauma frequently, but also have Participants

trauma-related symptoms. Schizophrenic patients with a All patients with a DSM-IV schizophrenic disorder [30] who

childhood sexual abuse history had higher levels of dis- were admitted consecutively to the Psychiatric Department of the

sociation, intrusive experiences, and state and trait anxi- Istanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty Hospital during

the 2-month study period (December 2005 to January 2006) were

ety than the non-abused schizophrenia group [26]. In a considered for participation. The diagnosis was confirmed by the

study covering adult traumas as well, two thirds of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-II) [31]. Ap-

patients reported clinically significant trauma symptoms proval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of

that included (at least) intrusive experiences, defensive the Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine. Patients who agreed to par-

avoidance, or dissociation. Delusions were correlated ticipate in the study provided written informed consent after the

study procedures had been fully explained.

with intrusive experiences, dissociation, and number of Reasons for exclusion were: severe cognitive impairment (n =

significantly elevated trauma scales, whereas hallucina- 2), psychosis too severe to cooperate (n = 4), and having received

tions were correlated with irritability and total number of electroconvulsive treatment during the 3-month period prior to

significantly elevated trauma scales [27]. Greater levels of the study interview (n = 2) . Among 79 patients who were eligible

depression and disturbance of volition were significantly for the study, 8 patients refused to participate and 1 patient was not

able to attend due to illiteracy. Seventy patients comprised the final

correlated with greater levels of anxious arousal, intru- study group. All patients were receiving neuroleptic drug treat-

sive experiences, defensive avoidance, dissociation, and ment as prescribed by their attending psychiatrists. Inpatients

the total number of significantly elevated trauma scales. (n = 21) attended the study interview after a stabilization period

In another study, schizophrenia itself seemed to be as- for an average duration of 14.9 days (SD = 6.5, range = 3–30).

sociated, independently of trauma and pathological post-

Instruments

traumatic conditions, with a broad range of dissociative Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The SCID is a semi-

symptoms [28]. Pronounced post-traumatic symptoms in structured interview developed by First et al. [31]. This widely

schizophrenia were associated with severe additional used interview serves as a diagnostic instrument for DSM-IV axis

34 Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 Sar /Taycan /Bolat /Özmen /Duran /

Öztürk /Ertem-Vehid

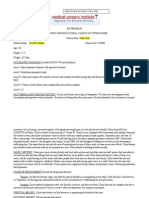

I psychiatric disorders, except for dissociative disorders. In order Table 1. Pearson correlations between DES, CTQ, and selected

to document the whole comorbidity spectrum on a phenomeno- clinical features (n = 70)

logical basis, all sections of the interview were conducted in the

present study, i.e., skipping parts of the interview due to the pres- Clinical characteristics DES score CTQ total score

ence of a supraordinate diagnostic category were not carried

r p r p

out.

Scales for the Assessment of Negative (SANS) and Positive

DES total score – – 0.38 0.001

(SAPS) Symptoms. Developed by Andreasen [32], the SAPS has 30

CTQ total score 0.36 0.002 – –

items, whereas the SANS has 20. Each item is scored on a 6-point

Secondary symptoms of DID 0.52 0.001 0.26 0.031

Likert-type scale by an interviewer. The SAPS has an interrater

Number of borderline

reliability of 0.84, whereas the SANS has an interrater reliability

personality disorder

of 0.60. Turkish versions of the scales have good reliability and

criteria (SCID-II) 0.48 0.001 0.31 0.009

validity as well [33, 34].

Extrasensory perceptions 0.40 0.001 0.34 0.004

Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES). The DES is a 28-item

Somatic complaints 0.33 0.005 0.29 0.025

self-report instrument developed by Bernstein and Putnam [35].

Schneiderian symptoms 0.29 0.002 0.06 0.644

It is not a diagnostic tool but serves as a screening device for

SCID diagnoses (lifetime) 0.41 0.001 0.19 0.125

chronic dissociative disorders with possible scores ranging from

SCID diagnoses (current) 0.33 0.005 0.07 0.546

0 to 100. The Turkish version of the scale has good reliability and

SANS 0.31 0.008 0.12 0.327

validity [36], with a cut-off score of 30 being useful for screening

SAPS 0.31 0.010 0.12 0.327

dissociative disorders [37].

Age –0.34 0.004 –0.05 0.668

Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS). The DDIS is

Age at onset of disorder –0.38 0.001 –0.05 0.667

a structured clinical interview consisting of 131 items. It was de-

Duration of disorder –0.08 0.509 –0.02 0.883

signed by Ross et al. [38] to diagnose somatization, major depres-

Education –0.15 0.227 –0.07 0.543

sion, borderline personality disorder, and 5 classes of dissociative

disorders according to DSM-IV. The schedule also inquires about

childhood abuse and neglect and a variety of features associated

with dissociative disorders including 11 Schneiderian symptoms,

16 secondary features of DID, and 16 extrasensory experiences.

The validity and reliability of the Turkish version has been re- a 4-group solution with the aim of having the opportunity to look

ported elsewhere [37]. into the distribution of both positive and negative symptoms of

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). The CTQ is a 28- schizophrenia among patients in each subgroup with high and

item self-report instrument developed by Bernstein et al. [39] that low dissociation. The subgroups derived by cluster analysis have

evaluates childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and been compared on various clinical features using one-way ANO-

childhood physical and emotional neglect. Possible scores for VA and the Fisher’s exact test. For all statistical analysis, p values

each type of childhood trauma range from 5 to 25. The sum of the were two-tailed and the level of significance was set at p = 0.05.

scores derived from each trauma type provides the total score

ranging from 25 to 125. Cronbach’s ␣ for the factors related to

each trauma type ranges from 0.79 to 0.94, indicating high inter-

nal consistency [39]. The scale also demonstrated good test-retest

reliability over a 2- to 6-month interval (intraclass correlation = Results

0.88).

Mean age of the patients was 38.3 years (SD = 11.3,

Statistical Analysis range = 19–59); 38 (54.3%) of them were women. They

Two-group comparisons on continuous variables were con- had 10.1 years (SD = 3.5, range = 5–20) of education on

ducted using the Student’s t test. The relationships of the CTQ and

DES with other variables were evaluated with the Pearson correla- average. Mean duration of schizophrenic disorder was

tion test. Predictive power of various types of childhood trauma 13.8 (SD = 9.3, range = 1–38) years. The overall patient

on DES scores were evaluated with stepwise linear regression group had a mean CTQ score of 43.6 (range = 27.0–80.0,

analysis. In order to clarify a potential heterogeneity in the study SD = 11.6) and a DES score of 18.1 (range = 0.0–73.9,

group, we preferred a k-means cluster analysis which classifies SD = 16.6). There was no significant difference between

subjects directly without pursuing a difference between variables

as either dependent or independent [40]. The k-means algorithm women (mean = 18.9, SD = 18.8) and men (mean = 17.2,

assigns each point to the cluster whose center (also called cen- SD = 13.8) on DES scores (t = 0.42, d.f. = 68, p = 0.679).

troid) is nearest. The center is the average of all the points in the Female (mean = 43.7, SD = 11.9) and male (mean = 43.6,

cluster – that is, its coordinates are the arithmetic mean for each SD = 11.4) patients did not differ on CTQ scores either

dimension separately over all the points in the cluster. The pur- (t = 0.03, d.f. = 68, p = 0.974).

pose of this method is to demonstrate the presence of patient sub-

groups with homogenous variables within groups and heteroge- Table 1 documents the findings from correlational

neity between groups, where the number of subgroups is to be analyses between various clinical measures. Age and DES

decided by the investigator but not the method itself. We preferred scores correlated negatively. There were significant cor-

Trauma and Dissociation in Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 35

Schizophrenia

relations not only between DES total scores and second- ary features of DID had significant correlations with

ary features of DID, but also borderline personality dis- CTQ total score, while Schneiderian symptoms did not.

order criteria, Schneiderian symptoms, extrasensory per- A stepwise linear regression analysis showed that among

ceptions, somatic complaints, number of lifetime and 6 variables (comprising age and 5 types of childhood

current SCID diagnoses, and negative and positive symp- traumas), only young age and childhood physical abuse

toms of schizophrenia. There were positive correlations and neglect predicted DES scores (table 2).

between CTQ and DES total scores. Among symptom We attempted to classify all patients through k-mean

groups, only borderline personality disorder criteria, ex- cluster analysis into 4 groups, while 11 variables entered

trasensory perceptions, somatic complaints, and second- the analysis: secondary features of DID, somatic com-

plaints, extrasensory perceptions, Schneiderian symp-

toms, borderline personality disorder criteria (SCID-II),

total numbers of current and lifetime SCID diagnoses,

Table 2. Stepwise linear regression analysis: types of childhood positive and negative symptom scores, total childhood

trauma as predictor of DES scores (F = 10.79, d.f. = 69, 3; p < trauma and DES scores (table 3). Group A (n = 13) and

0.001) group B (n = 5) consisted of patients with the most robust

dissociative symptomatology, such as secondary features

SE  t p OR and 95% CI

of DID and elevated DES scores. They also had more

Childhood trauma scores Schneiderian symptoms, extrasensory perceptions, so-

Physical neglect 0.52 0.28 2.57 0.013 1.35 (0.30–2.39) matic complaints, and borderline personality disorder

Physical abuse 0.60 0.28 2.60 0.011 1.56 (0.36–2.76) criteria than the remaining groups. Both groups A and B

Age (younger) 0.15 0.37 3.63 0.001 0.54 (0.24–0.84)

had elevated childhood trauma scores, except for emo-

Constant 7.43 – 2.23 0.029 16.58 (1.75–31.41)

tional neglect (table 4). A significant majority of patients

Table 3. Differences between 4 patient groups derived through k-mean cluster analysis

Symptom clusters and scale scores High-dissociation groups Low-dissociation groups 1-way variance

analysis

group A group B group C group D F p

(n = 13) (n = 5) (n = 10) (n = 42) (d.f. = 3, 69)

Schneiderian symptoms (DDIS) 7.683.2 7.881.3 6.182.4 4.883.5 3.53 0.019

Somatic complaints (DDIS) 9.887.4 8.085.3 2.582.2 4.083.7 7.18 0.001

Secondary features of DID (DDIS) 5.883.3 7.283.4 3.582.8 3.182.2 6.38 0.001

Extrasensory perceptions (DDIS) 4.582.7 4.282.0 1.982.6 1.481.5 9.74 0.001

Borderline personality disorder criteria (SCID-II) 4.782.9 2.882.6 0.380.5 1.681.5 13.51 0.001

SCID diagnoses (current) 2.881.1 2.081.2 2.480.7 1.681.0 5.84 0.001

SCID diagnoses (lifetime) 3.581.3 2.880.8 2.681.0 2.381.0 4.47 0.006

SANS 51.7823.0 46.6814.0 80.0823.9 28.0813.7 26.32 0.001

PANS 40.5815.6 106.4817.9 61.1821.5 17.9816.2 52.02 0.001

DES total score 40.0815.8 38.5812.4 12.5811.0 10.388.7 31.59 0.001

Childhood trauma scores

Emotional neglect 13.885.1 13.885.6 13.484.3 12.983.8 0.17 0.914

Physical neglect 11.184.4 10.081.9 7.682.6 8.083.1 3.67 0.016

Emotional abuse 10.583.5 12.485.5 6.481.8 8.184.3 3.59 0.018

Physical abuse 8.884.5 7.482.8 5.580.8 6.382.5 3.37 0.024

Sexual abuse 8.183.9 6.481.9 5.481.0 6.182.1 2.84 0.044

CTQ total score 52.2810.4 50.0813.4 38.387.9 41.5811.1 4.72 0.005

Age, years 32.5810.1 34.6818.1 36.4813.6 41.089.7 2.33 0.083

Age of onset of the disorder, years 21.484.7 18.282.4 23.687.7 26.488.6 2.73 0.051

Duration of the disorder, years 11.188.8 16.4816.3 12.888.8 14.189.2 0.50 0.685

Education, years 9.283.2 10.283.4 9.083.7 10.683.5 0.96 0.418

36 Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 Sar /Taycan /Bolat /Özmen /Duran /

Öztürk /Ertem-Vehid

who fit the DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality Discussion

disorder were in the dissociative group (table 4). Very few

patients had a current or lifetime diagnosis of PTSD or As shown by correlations between symptoms and

substance abuse. mental health history items, and an independent cluster

While the overall number of psychiatric comorbidities analysis, the present study documented the existence of

was correlated with DES scores, none of the comorbid a dissociative subgroup among schizophrenic patients.

psychiatric diagnoses was associated exclusively with the Notwithstanding the need for further research to estab-

dissociative subgroup. Although positive symptoms of lish its validity, this finding supports a dissociative sub-

schizophrenia predominated in group B, group A was type of schizophrenia as proposed by Ross [22]. This sub-

characterized by both positive and negative symptoms. group did not overlap with any of the classical subtypes

Group A had the highest scores on childhood sexual and of schizophrenia (table 4). The relationship of positive

physical abuse. They had more diagnoses of concurrent and negative symptoms of schizophrenia with a dissocia-

mood and anxiety disorder than group B. On the other tive subtype was also heterogenous (table 3). Thus, the

hand, group B had the highest scores on childhood emo- dissociative subtype of schizophrenia represents a para-

tional abuse. There was no relationship between tradi- digm different from previous ones.

tional subtypes of schizophrenia and the subgroups de- Three previous studies documented that patients with

rived by cluster analysis (table 4), and gender also was not schizophrenic disorder and a high level of dissociation

related to any of them. report childhood traumas more frequently than non-dis-

sociative schizophrenic patients [8, 10, 21]. Indeed, there

were significant correlations between DES and CTQ total

scores in the present study. There were also significant

correlations between CTQ total score and secondary

Table 4. Differences between 4 patient groups derived through k-mean cluster analysis

High-dissociation groups Low-dissociation groups Fisher’s

exact test

group A (n = 13) group B (n = 5) group C (n = 10) group D (n = 42)

p

n % n % n % n %

Subtypes of schizophrenia (SCID-II)

Paranoid 6 46.2 2 40.0 4 40.0 18 42.9 1.000

Catatonic 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 2.4 1.000

Disorganized 2 15.4 2 40.0 2 20.0 3 7.1 0.102

Undifferentiated 3 23.1 1 10.0 1 10.0 7 16.7 0.873

Residual 2 15.4 0 0.0 3 30.0 13 31.0 0.453

Psychiatric Comorbidity (SCID-II)

Any adjustment disorder (current) 4 30.8 2 40.0 3 30.0 7 16.7 0.369

Any adjustment disorder (lifetime) 4 30.8 2 40.0 3 30.0 14 33.3 1.000

Any somatoform disorder (current) 2 15.4 1 20.0 1 10.0 0 0.0 0.023

Any somatoform disorder (lifetime) 2 15.4 1 20.0 2 20.0 0 0.0 0.023

Any anxiety disorder (current) 8 61.5 0 0.0 4 40.0 10 23.8 0.027

Any anxiety disorder (lifetime) 9 69.2 2 40.0 4 40.0 15 35.7 0.202

Any mood disorder (current) 8 61.5 1 20.0 6 60.0 8 19.0 0.005

Any mood disorder (lifetime) 11 84.6 3 60.0 7 70.0 24 57.1 0.334

PTSD (current) 1 7.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0.400

PTSD (lifetime) 1 7.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 4.8 0.790

Substance use (current) 0 0.0 1 20.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1.000

Substance use (lifetime) 1 7.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 9.5 0.877

Borderline personality disorder 7 53.8 2 40.0 0 0.0 2 4.8 0.001

Female 8 61.5 3 60.0 2 20.0 25 59.5 0.135

Trauma and Dissociation in Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 37

Schizophrenia

symptoms of DID alongside somatic complaints, extra- Significant overlap between any of the disorders may

sensory perceptions, and borderline personality disorder arise for several reasons. In addition to shared risk factors

criteria (table 2), which are known to be part of dissocia- or fuzzy boundaries between the diagnoses, one of the

tive disorders [38]. However, CTQ scores were not related disorders may itself be a risk factor for the other. While

to positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia and, the introduction of a dissociative subtype of schizophre-

in contrast to a previous study [41], neither to Schneide- nia has advantages in terms of clinical utility, it does not

rian symptoms. Unlike childhood trauma scores, disso- necessarily suggest the validity of a categorical model and

ciative experiences were correlated with negative and the same solution may fit with a dimensional approach as

positive symptoms of schizophrenia and Schneiderian well. Notwithstanding the possibility of a clinical spec-

symptoms as well (table 1). Thus, the present study sug- trum from dissociation to schizophrenia either, we also

gests that childhood trauma is related to concurrent dis- consider a duality (interaction) model to explain complex

sociation rather than to core features of schizophrenia, co-existence of 2 distinct but concurrent or subsequent

while there was a more proximal relationship between psychopathologies as a possibility [47].

schizophrenia and dissociation [29]. In fact, the notion of a relatively healthy part of per-

Representing a nosological fragmentation, high gen- sonality not affected by prevailing psychopathology is

eral psychiatric comorbidity is a phenomenon observed not new in psychiatry, including Bleuler’s original con-

among traumatized psychiatric populations in particular ceptualization of schizophrenia as ‘split mind’ (or split-

[42]. In accordance with this observation, dissociation ting of psychological functions) and in contrast to the

scores were correlated with total number of current and ‘dementia praecox’ of Kraepelin [48]. Most recently, this

lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders, while none of notion has been revived under the rubric of the struc-

the comorbid DSM-IV [30] axis-I diagnoses was associ- tural dissociation model of personality as its modern ver-

ated exclusively with the dissociative subtype of schizo- sion [49, 50]. In application of Bleuler’s notion about a

phrenia. Nevertheless, a statistically significant number healthy part onto the structural dissociation model of

of patients with borderline personality disorder diagnosis personality, the duality model assumes coexistence and

belonged to the high-dissociation group (table 4). Previ- interaction between two qualitatively distinct psychopa-

ous studies documented a large overlap between border- thologies depending on whether dissociation functions

line personality disorder and dissociative disorders, in- as a source of resilience against, a risk factor for, or a re-

cluding high frequencies of reported childhood trauma sponse to a schizophrenic disorder. One of the assump-

[43]. In a previous study on patients with schizophrenia, tions is that dissociation may function as a defense against

higher levels of borderline traits were uniquely related to or a facade before an intrapsychic threat of schizophren-

the report of childhood sexual abuse [44]. It is possible ic psychopathology becomes manifest, historically de-

that borderline personality disorder criteria represent a scribed in diverse ways depending on prevailing concep-

trauma-related symptom pattern among patients with tualizations such as pseudoneurotic schizophrenia [51].

schizophrenic disorder rather than a personality disorder Although this defense may prevent the progression of, or

per se. encapsulate, the severe psychopathology for some sub-

In the present study, young age and childhood physi- jects, it may make the condition more complex for others

cal abuse and neglect predicted dissociation. Dissociative and even constitutes the pathway leading to a severer

experiences are known to be negatively correlated with mental illness [52]. In addition, coping with the lifelong

age, both in clinical and non-clinical populations [36, 37]. experience of having a chronic and devastating mental

While being the most frequently reported types of child- illness may require adaptive dissociative mechanisms,

hood adverse experiences in Turkey [45], physical abuse such as denial of the disorder, social detachment, mental

and neglect also may start to take effect at an earlier age absorption, change of perception of the self and the envi-

compared to other types of childhood trauma. In support ronment, and identity disturbances. A similar interac-

of its culture-free impact, childhood physical neglect was tion model has been proposed for PTSD and severe men-

predictor of adult dissociation among schizophrenic pa- tal illness by several authors [53, 54]. A psychotic episode

tients in a recent study from Germany as well [46]. There can itself be a cause of PTSD as well which may even lead

were no gender differences on childhood trauma and dis- to suicide attempts [55]. Although in its infancy, we hope

sociation scores, pointing to a common factor affecting that the duality hypothesis may serve as a starting point

both genders in context of a severe mental illness. for further research in this field of complex comorbid-

ity.

38 Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 Sar /Taycan /Bolat /Özmen /Duran /

Öztürk /Ertem-Vehid

The present study has several limitations. First of all, power and sample size do not arise [57]. The only sample

the study group consisted of chronic patients with long- size issue is whether or not the sample is representative

term psychiatric history. Moreover, all patients were re- enough to allow generalizations to be made. Thus, as the

ceiving neuroleptic drug treatment and the study assess- sample is representative only for chronic patients, the

ment was conducted after a stabilization phase for some present study does not allow generalizations to patients

of them. A study on first-episode schizophrenia and in early stages of the disorder.

medication-free patients may lead to different results.

Second, the assessment instruments were not designed

specifically for identifying qualitative differences be- Conclusions

tween symptoms which are common in both disorders,

e.g. Schneiderian symptoms and hallucinations [56]. In support of an earlier proposal for a dissociative sub-

Third, childhood trauma reports are of retrospective na- type of schizophrenia, the present study documented that

ture; thus, they are subject to possible reinterpretation there is a subgroup of schizophrenic patients who have

and are also susceptible to distortions by psychopathol- dissociative symptoms and childhood trauma history

ogy. However, this may happen in both directions. As more frequently than the remaining patients. Overall,

aversive contents, childhood traumas can be subject to childhood trauma seems to be related to concurrent dis-

minimization or denial as well [11]. Fourth, in consider- sociation rather than to core features of schizophrenic

ation of the multivariate statistical method used in this disorder. The complex relationship between 2 psychopa-

study, the relatively small sample size may also be consid- thologies and/or childhood trauma requires further study

ered as a limitation. Nevertheless, k-means clustering based on diverse models of psychopathology.

does not involve any significance testing, so issues of

References

1 Putnam FW: Dissociation in Children and 8 Holowka DV, King S, Sahep D, Pukal M, Bru- 14 Read J, Van Os J, Morrison AP, Ross CA:

Adolescents. A Developmental Perspective. net A: Childhood abuse and dissociative Childhood trauma, psychosis, and schizo-

New York, Guilford, 1997. symptoms in adult schizophrenia. Schizophr phrenia: a literature review with theoretical

2 Tutkun H, Sar V, Yargic LI, Özpulat T, Kizil- Res 2003;60:87–90. and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr

tan E, Yanik M: Frequency of dissociative 9 Schäfer I, Harfst T, Aderhold V, Briken P, Scand 2005;112:330–350.

disorders among psychiatric inpatients in a Lehmann M, Moritz S, Read J, Naber D: 15 Read J, Fink PJ, Rudegeair T, Felitti V, Whit-

Turkish university clinic. Am J Psychiatry Childhood trauma and dissociation in fe- field CL: Child maltreatment and psychosis:

1998;155:800–805. male patients with schizophrenia spectrum a return to a genuinely integrated bio-psy-

3 Sar V, Akyüz G, Dogan O: Prevalence of dis- disorders: an exploratory study. J Nerv Ment cho-social model. Clin Schizophr Relat Dis

sociative disorders among women in the Dis 2006;194:135–138. 2008;2:235–254.

general population. Psychiatry Res 2007;149: 10 Ross CA, Keyes B: Dissociation and schizo- 16 Morgan C, Fisher H: Environmental factors

169–176. phrenia. J Trauma Dissociation 2004; 5: 69– in schizophrenia: childhood trauma – a crit-

4 Putnam FW, Guroff JJ, Silberman EK, Bar- 83. ical review. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33:3–10.

ban L, Post RM: The clinical phenomenolo- 11 Spence W, Mulholland C, Lynch G, McHugh 17 Read J, Perry BD, Moskowitz A, Connolly J:

gy of multiple personality disorder: review of S, Dempster M, Shannon C: Rates of child- The contribution of early traumatic events to

100 recent cases. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47: hood trauma in a sample of patients with schizophrenia in some patients: a trauma-

285–293. schizophrenia as compared with a sample of genic neurodevelopmental model. Psychia-

5 Ross CA, Norton GR, Wozney K: Multiple non-psychotic psychiatric diagnoses. J Trau- try 2001;64:319–345.

personality disorder: an analysis of 236 cas- ma Dissociation 2006;7:7–22. 18 Green AI, Canuso CM, Brenner MJ, Wojcik

es. Can J Psychiatry 1989;34:413–418. 12 Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen JD: Detection and management of comor-

6 Ogawa JR, Sroufe LA, Weinfield NS, Carlson M, Vollebergh W, DeGraaf R, et al: Child- bidity in patients with schizophrenia. Psy-

EA, Egeland B: Development and the frag- hood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic ex- chiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:115–139.

mented self: longitudinal study of dissocia- periences. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 109: 19 Brunner R, Parzer P, Schmitt R, Resch F: Dis-

tive symptomatology in a nonclinical sam- 38–45. sociative symptoms in schizophrenia: a com-

ple. Dev Psychopathol 1997; 9:855–879. 13 Kilcommons AM, Morrison AP: Relation- parative analysis of patients with borderline

7 Lewis DO, Yeager CA, Swica Y, Pincus JH, ships between trauma and psychosis: an ex- personality disorder and healthy controls.

Lewis M: Objective documentation of child ploration of cognitive and dissociative fac- Psychopathology 2004; 37:281–284.

abuse and dissociation in 12 murderers with tors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005; 112: 251– 20 Spitzer C, Haug HJ, Freyberger HJ: Dissocia-

dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychia- 259. tive symptoms in schizophrenic patients

try 1997;154:1703–1710. with positive and negative symptoms. Psy-

chopathology 1997; 30:67–75.

Trauma and Dissociation in Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 39

Schizophrenia

21 Glaslova K, Bob P, Jasova D, Bratkova N, Pta- 32 Andreasen NC: Methods for assessing posi- 46 Vogel M, Spitzer C, Kuwert P, Möller B, Frey-

cek R: Traumatic stress and schizophrenia. tive and negative symptoms. Mod Probl berger HJ, Grabe HJ: Association of child-

Neurol Psychiat Brain Res 2004; 11: 205– Pharmacopsychiatry 1990;24:73–88. hood neglect with adult dissociation in

208. 33 Erkoc S, Arkonac O, Atakli C, Özmen E: schizophrenic inpatients. Psychopathology

22 Ross CA: Schizophrenia: Innovations in Negatif semptomlari degerlendirme ölce- 2009;42:124–130.

Diagnosis and Treatment. Birmingham, ginin güvenilirligi ve gecerligi. (Reliability 47 Sar V, Öztürk E: Psychotic symptoms in

Haworth, 2004. and validity of the Turkish version of nega- complex dissociative disorders; in Mosko-

23 Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H: The complex tive symptoms scale). Düsünen Adam 1991; witz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy MJ (eds): Psycho-

overlap between dissociation and schizo- 4:16–19. sis, Trauma and Dissociation: Emerging

typy; in Moskowitz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy MJ 34 Erkoc S, Arkonac O, Atakli C, Özmen E: Po- Perspectives on Severe Psychopathology.

(eds): Psychosis, Trauma and Dissociation: zitif semptomlari degerlendirme ölceginin London, Wiley & Sons, 2008, pp 165–175.

Emerging Perspectives on Severe Psychopa- güvenilirligi ve gecerligi (Reliability and va- 48 Middleton W, Dorahy MJ, Moskowitz A:

thology. London, Wiley & Sons, 2008, pp 79– lidity of the Turkish version of positive Historical conceptions of dissociation and

89. symptoms scale). Düsünen Adam 1991;4:20– psychosis: nineteenth and early twentieth

24 Schenkel LS, Spaulding WD, DiLillo D, Sil- 24. century perspectives on severe psychopa-

verstein SM: Histories of childhood mal- 35 Bernstein EM, Putnam PW: Development, thology; in Moskowitz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy

treatment in schizophrenia: relationships reliability and validity of a dissociation scale. MJ (eds): Psychosis, Trauma and Dissocia-

with premorbid functioning, symptomatol- J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;174:727–735. tion: Emerging Perspectives on Severe Psy-

ogy and cognitive deficits. Schizophr Res 36 Yargic LI, Tutkun H, Sar V: The reliability chopathology. London, Wiley & Sons, 2008,

2005;76:273–286. and validity of the Turkish version of the pp 9–19.

25 Read J, Agar K, Argyle N, Aderhold V: Sexu- Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation 49 Van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ERS, Steele K:

al and physical abuse during childhood and 1995;8:10–13. Structural dissociation of the personality; in

adulthood as predictors of hallucinations, 37 Yargic LI, Sar V, Tutkun H, Alyanak B: Com- Van der Hart O (ed): The Haunted Self.

delusions and thought disorder. Psychol Psy- parison of dissociative identity disorder with Structural Dissociation and the Treatment

chother 2003;76:1–22. other diagnostic groups using a structured of Chronic Traumatization. New York, Nor-

26 Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Gatton MJ, Herman interview in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry 1998; ton, 2006, pp 23–132.

SM: Associations of anxiety-related symp- 39:345–351. 50 Ross CA: Paraphilia from a dissociative per-

toms with reported history of childhood sex- 38 Ross CA, Heber S, Norton GR, Anderson D, spective. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2008; 31:

ual abuse in schizophrenia spectrum disor- Anderson G, Barchet P: The Dissociative 613–622.

ders. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1279–1284. Disorders Interview Schedule: a structured 51 Hoch P, Polatin P: Pseudoneurotic forms of

27 Lysaker PH, LaRocco VA: The prevalence interview (translated and adapted into Turk- schizophrenia. Psychiatric Q 1949; 23: 248–

and correlates of trauma-related symptoms ish by Sar V, Tutkun H, Yargic LI, Istanbul, 276.

in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Compr 1993). Dissociation 1989;2:169–172. 52 Volkan VD: The Infantile Psychotic Self and

Psychiatry 2008;49:330–334. 39 Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote Its Fates. London, Jason Aronson, 1995.

28 Vogel M, Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, et al: Initial reliabil- 53 Spitzer C, Vogel M, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ,

Grabe HJ: The role of trauma and PTSD-re- ity and validity of a new retrospective mea- Grabe HJ: Psychopathology and alexithymia

lated symptoms for dissociation and psycho- sure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psy- in severe mental illness: the impact of trau-

pathological distress in inpatients with chiatry 1994;151:1132–1136. ma and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Eur

schizophrenia. Psychopathology 2006; 39: 40 Anderberg MR: Cluster Analysis for Appli- Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 257:

236–242. cations. New York, Academic Press, 1973. 191–196.

29 Vogel M, Schatz D, Spitzer C, Kuwert P, 41 Ross CA, Joshi S: Schneiderian symptoms 54 Tarrier N, Khan S, Cather J, Picken A: The

Moller B, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ: A more and childhood trauma in the general popula- subjective consequences of suffering a first

proximal impact of dissociation than of tion. Compr Psychiatry 1992;33:269–273. episode psychosis: trauma and suicide be-

trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder on 42 Sar V, Ross CA: Dissociative disorders as a havior. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

Schneiderian symptoms in patients diag- confounding factor in psychiatric research. 2007;42:29–35.

nosed with schizophrenia. Compr Psychia- Psychiatr Clin North Am 2006;29:129–144. 55 Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA,

try 2009;50:128–139. 43 Sar V, Akyuz G, Kugu N, Ozturk E, Ertem- Trumbetta SL: Trauma, PTSD and the course

30 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnos- Vehid H: Axis-I dissociative disorder comor- of severe mental illness: an interactive mod-

tic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor- bidity in borderline personality disorder and el. Schizophr Res 2002;53:123–143.

ders, ed 4. Washington, American Psychiat- reports of childhood trauma. J Clin Psychia- 56 Kluft RP: First rank symptoms as a diagnos-

ric Association, 1994. try 2006;67:1583–1590. tic clue to multiple personality disorder. Am

31 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams 44 Lysaker PH, Wickett AM, Lancaster RS, Da- J Psychiatry 1987;144:293–298.

JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM- vis LW: Neurocognitive deficits and history 57 Everitt BS: Cluster Analysis. New York,

IV Axis I Disorders: Clinician Version of childhood abuse in schizophrenia spec- Wiley, 1993.

(SCID-CV), User’s Guide. Washington, trum disorders: associations with cluster B

American Psychiatric Association, 1997. personality traits. Schizophr Res 2004; 68:

87–94.

45 Akyüz G, Sar V, Kugu N, Dogan O: Reported

childhood trauma, attempted suicide and

self-mutilative behavior among women in

the general population. Eur Psychiatry 2005;

20:268–273.

40 Psychopathology 2010;43:33–40 Sar /Taycan /Bolat /Özmen /Duran /

Öztürk /Ertem-Vehid

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Becker 2007Document6 pagesBecker 2007Stroe EmmaNo ratings yet

- Larsson Et Al. (2013) - High Prevalence of Childhood Trauma in Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum and Affective DisorderDocument5 pagesLarsson Et Al. (2013) - High Prevalence of Childhood Trauma in Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum and Affective Disorderlixal5910No ratings yet

- Cumulative Effects of Childhood Traumas - Polytraumatization, Dissociation, and Schizophrenia PDFDocument10 pagesCumulative Effects of Childhood Traumas - Polytraumatization, Dissociation, and Schizophrenia PDFguswendyw_201473766No ratings yet

- Comorbid Anxiety and Depression - Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis PDFDocument24 pagesComorbid Anxiety and Depression - Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis PDFdreaming0% (1)

- Association Between Specific Childhood Adversities and Symptom Dimensions in People With Psychosis - Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesAssociation Between Specific Childhood Adversities and Symptom Dimensions in People With Psychosis - Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSusana Pérez ReyesNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Children and AdolescentsDocument19 pagesHHS Public Access: Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescentsayub01No ratings yet

- The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder in An Anxiety ClinicDocument7 pagesThe Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder in An Anxiety Clinicyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder in An Anxiety ClinicDocument7 pagesThe Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder in An Anxiety ClinicMaysoun AtoumNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Anomalous Self-E PDFDocument5 pagesThe Association Between Anomalous Self-E PDFferny zabatierraNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Inga Schalinski, Yolanda Fischer, Brigitte RockstrohDocument8 pagesPsychiatry Research: Inga Schalinski, Yolanda Fischer, Brigitte RockstrohAndra AndruNo ratings yet

- Journal 2Document8 pagesJournal 2pososuperNo ratings yet

- Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD SX Complexity Cloitre Et AlDocument11 pagesDevelopmental Approach To Complex PTSD SX Complexity Cloitre Et Alsaraenash1No ratings yet

- Visual Height Intolerance and Acrophobia: Distressing Partners For LifeDocument8 pagesVisual Height Intolerance and Acrophobia: Distressing Partners For LifeAnonymous OCVES8U7No ratings yet

- Developmental and Clinical Predictors of Comorbidity For Youth With OCDDocument7 pagesDevelopmental and Clinical Predictors of Comorbidity For Youth With OCDViktória Papucsek LelkesNo ratings yet

- Psychopathological Mechanisms Linking Childhood Traumatic ExperiencesDocument8 pagesPsychopathological Mechanisms Linking Childhood Traumatic Experiencessaurav.das2030No ratings yet

- Mental HealthDocument8 pagesMental HealthJohn TelekNo ratings yet

- Relationship, Socialsupport, Andpersonalitya Spsychosocialdeterminantsoftherisk ForpostpartumbluesDocument9 pagesRelationship, Socialsupport, Andpersonalitya Spsychosocialdeterminantsoftherisk ForpostpartumbluesKA HendraNo ratings yet

- Cristin 10 PBDocument10 pagesCristin 10 PBKA HendraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Psikiatri 3Document6 pagesJurnal Psikiatri 3LannydchandraNo ratings yet

- Insight and Self-Stigma in Patients With Schizophrenia: Domagoj Vidović, Petrana Brečić, Maja Vilibić and Vlado JukićDocument6 pagesInsight and Self-Stigma in Patients With Schizophrenia: Domagoj Vidović, Petrana Brečić, Maja Vilibić and Vlado JukićAnđela MatićNo ratings yet

- Renkema, 2020Document9 pagesRenkema, 2020Zeynep ÖzmeydanNo ratings yet

- Varghese 2011 Psychotic Like Experiences in Major Depression and Anxiety DisordersDocument5 pagesVarghese 2011 Psychotic Like Experiences in Major Depression and Anxiety DisordersJuan Morales TapiaNo ratings yet

- Rao Chen 2009. DialoguesClinNeurosci-11-45Document18 pagesRao Chen 2009. DialoguesClinNeurosci-11-45Javiera Luna Marcel Zapata-SalazarNo ratings yet

- Beyond Trauma: A Multiple Pathways Approach To Auditory Hallucinations in Clinical and Nonclinical PopulationsDocument8 pagesBeyond Trauma: A Multiple Pathways Approach To Auditory Hallucinations in Clinical and Nonclinical PopulationsScott McCullaghNo ratings yet

- JAMWA Article - HopenwasserDocument24 pagesJAMWA Article - HopenwasserSex & Gender Women's Health CollaborativeNo ratings yet

- Članak ShizofrenijaDocument6 pagesČlanak ShizofrenijaIvanNo ratings yet

- Developmental Profiles SchizotipyDocument23 pagesDevelopmental Profiles SchizotipyDavid MastrangeloNo ratings yet

- Genetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDocument16 pagesGenetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Disorders Among Adolescents Referred To General Psychiatry For Multiple Causes: Clinical Presentation, Prevalence, and ComorbidityDocument10 pagesAnxiety Disorders Among Adolescents Referred To General Psychiatry For Multiple Causes: Clinical Presentation, Prevalence, and ComorbidityRatu CalistaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Comorbid Psychopathology in Youth With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Comorbid Psychopathology in Youth With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresCecilia FRNo ratings yet

- Davydow 2010 Psychiatric MorbidityDocument9 pagesDavydow 2010 Psychiatric MorbidityAndrew EdisonNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in The Physical and Psychological Manifestation of Childhood TraumaDocument8 pagesGender Differences in The Physical and Psychological Manifestation of Childhood TraumasingernoraNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Jack Tsai, Robert A. RosenheckDocument5 pagesPsychiatry Research: Jack Tsai, Robert A. RosenheckRaj DesaiNo ratings yet

- Somatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDocument9 pagesSomatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDũng HồNo ratings yet

- Pietrzak 2013Document1 pagePietrzak 2013MikerenNo ratings yet

- Barzilay PatrickDocument10 pagesBarzilay PatrickZeynep ÖzmeydanNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Schizo-Affective, Schizophrenic and Mood Disorders in Patients Admitted at Mathari Psychiatric Hospital, Nairobi, KenyaDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Schizo-Affective, Schizophrenic and Mood Disorders in Patients Admitted at Mathari Psychiatric Hospital, Nairobi, KenyaLunaFiaNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Treating Anxiety Disor PDFDocument38 pagesUnderstanding and Treating Anxiety Disor PDFEloued SiryneNo ratings yet

- Self-Esteem Epilepsy & BehaviorDocument5 pagesSelf-Esteem Epilepsy & Behaviornathália_siqueira_47No ratings yet

- Suicide Attempts in Hospital-Treated Epilepsy Patients: Radmila Buljan and Ana Marija ŠantićDocument6 pagesSuicide Attempts in Hospital-Treated Epilepsy Patients: Radmila Buljan and Ana Marija Šantićprodaja47No ratings yet

- 2019 Lukasz PDFDocument24 pages2019 Lukasz PDFnermal93No ratings yet

- s1 Evidence+thatDocument13 pagess1 Evidence+thatMarcelitaTaliaDuwiriNo ratings yet

- Chen2016 Article Self-stigmaAndAffiliateStigmaIDocument7 pagesChen2016 Article Self-stigmaAndAffiliateStigmaIFemin PrasadNo ratings yet

- Journal of Psychosomatic Research: Ella Bekhuis, Lynn Boschloo, Judith G.M. Rosmalen, Robert A. SchoeversDocument7 pagesJournal of Psychosomatic Research: Ella Bekhuis, Lynn Boschloo, Judith G.M. Rosmalen, Robert A. SchoeversDũng HồNo ratings yet

- Gender Dysphoria and Social AnxietyDocument9 pagesGender Dysphoria and Social AnxietyJellybabyNo ratings yet

- Morgades Bamba2019 PDFDocument7 pagesMorgades Bamba2019 PDFArif IrpanNo ratings yet

- Beesdo Baum2012Document15 pagesBeesdo Baum2012akzarajuwanaparastiaraNo ratings yet

- A Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma As Predictors of Symptom Complexity.Document10 pagesA Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma As Predictors of Symptom Complexity.macrabbit8100% (1)

- Relación Entre Psicopatología Adulta y Antecedentes de Trauma InfantilDocument9 pagesRelación Entre Psicopatología Adulta y Antecedentes de Trauma InfantilDanielaMontesNo ratings yet

- Irritabiity - Brotman2017Document13 pagesIrritabiity - Brotman2017Caio MayrinkNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Etiology, Pathophysiology and Management - A ReviewDocument7 pagesSchizophrenia: Etiology, Pathophysiology and Management - A ReviewFausiah Ulva MNo ratings yet

- PCP v5n4p289 enDocument8 pagesPCP v5n4p289 enDevana MaelissaNo ratings yet

- Treatment Refractory Schizophrenia in Children and Adolescents. An Update On Clozapine and Other Pharmacologic InterventionsDocument25 pagesTreatment Refractory Schizophrenia in Children and Adolescents. An Update On Clozapine and Other Pharmacologic Interventionstoshi setiahadiNo ratings yet

- Halusi JurnalDocument16 pagesHalusi JurnalVitta ChusmeywatiNo ratings yet

- Hanza Wa 2013Document6 pagesHanza Wa 2013MicciNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Illness Phases in Schizophrenia A Non Parametric Item Response Analysis of The Positive and Negative Syndrome ScaleDocument37 pagesThe Evolution of Illness Phases in Schizophrenia A Non Parametric Item Response Analysis of The Positive and Negative Syndrome ScaleLasharia ClarkeNo ratings yet

- Correlatos Del Maltrato Físico en La Infancia en Mujeres Adultas Con Trastorno Distímico o Depresión MayorDocument8 pagesCorrelatos Del Maltrato Físico en La Infancia en Mujeres Adultas Con Trastorno Distímico o Depresión MayormagdaNo ratings yet

- SaadaDocument7 pagesSaadaAnonymous KrfJpXb4iNNo ratings yet

- Depression Conceptualization and Treatment: Dialogues from Psychodynamic and Cognitive Behavioral PerspectivesFrom EverandDepression Conceptualization and Treatment: Dialogues from Psychodynamic and Cognitive Behavioral PerspectivesChristos CharisNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic System: Why the Classification of Psychiatric Disorders Is Necessary, Difficult, and Never SettledFrom EverandDiagnostic System: Why the Classification of Psychiatric Disorders Is Necessary, Difficult, and Never SettledNo ratings yet

- H.4 Borderline PowerPoint Revised 2015Document31 pagesH.4 Borderline PowerPoint Revised 2015Ptrc Lbr LpNo ratings yet

- Peer Support For PeopleDocument120 pagesPeer Support For Peoplebraulio rojasNo ratings yet

- Essay On Catcher in The RyeDocument6 pagesEssay On Catcher in The Ryeezmnkmjv100% (2)

- Borderline Personality Disorder Otto F. Kernberg M.D.Robert Michels M.DDocument5 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder Otto F. Kernberg M.D.Robert Michels M.DДанило ПисьменнийNo ratings yet

- 2012 Sepa ConferenceDocument102 pages2012 Sepa ConferenceGaia NievesNo ratings yet

- Manual 2 Day Trauma Conference BesselDocument50 pagesManual 2 Day Trauma Conference Besselcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- @2018 em Southward ER, ERP RDocument17 pages@2018 em Southward ER, ERP RChelsey XieNo ratings yet

- Psych Student NotesDocument23 pagesPsych Student NotesReymund Timog TalarocNo ratings yet

- Hostile Aggressive ParentingReccommendationsDocument87 pagesHostile Aggressive ParentingReccommendationsDestiny Ann100% (2)

- 4 - Kiehn, B & Swales, M. (2007) - An Overview of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in The Treatment ofDocument9 pages4 - Kiehn, B & Swales, M. (2007) - An Overview of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in The Treatment ofAnastasiya PlohihNo ratings yet

- Emotional Abuse Recovery Work BookDocument159 pagesEmotional Abuse Recovery Work BookDaniel Aberle100% (9)

- Psych Careplan For PaperDocument18 pagesPsych Careplan For PaperUSMCDOC100% (2)

- Badoud, Prada, Nicastro Et Al. (2018) Attachment and Reflective Functioning in Women With BPDDocument14 pagesBadoud, Prada, Nicastro Et Al. (2018) Attachment and Reflective Functioning in Women With BPDLetteratura ArabaNo ratings yet

- Human Behavior and VictiminologyDocument20 pagesHuman Behavior and VictiminologyKhristel Alcayde100% (1)

- ReportDocument31 pagesReportgunratna kambleNo ratings yet

- Zanarini Rating Scale For Borderline Zanarini2003Document10 pagesZanarini Rating Scale For Borderline Zanarini2003Cesar CantaruttiNo ratings yet

- Arntz Dietzel Dreessen 99Document13 pagesArntz Dietzel Dreessen 99calmeida_31No ratings yet

- Rossouw and Fonagy JAACAP 2012Document14 pagesRossouw and Fonagy JAACAP 2012Lina SantosNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatric Review of Symptoms - A Screening Tool For Family Physicians - American Family PhysicianDocument7 pagesThe Psychiatric Review of Symptoms - A Screening Tool For Family Physicians - American Family PhysicianTimothy TurscakNo ratings yet

- Personality Types 2 Day WorkshopDocument144 pagesPersonality Types 2 Day WorkshopDoru PatruNo ratings yet

- Taylor-Black & Vasser (2008) Famca 335Document62 pagesTaylor-Black & Vasser (2008) Famca 335familylawdirectoryNo ratings yet

- Session 4+5 - Dark Personalities - 21571508 - 2023 - 11 - 19 - 07 - 10Document136 pagesSession 4+5 - Dark Personalities - 21571508 - 2023 - 11 - 19 - 07 - 10asshubhamsinhaNo ratings yet

- Jam Rodriguez Activity #4Document7 pagesJam Rodriguez Activity #4Sandra GabasNo ratings yet

- Complex PTSD - A Better Description For Borderline Personality Disorder?Document3 pagesComplex PTSD - A Better Description For Borderline Personality Disorder?Nicolás MaturanaNo ratings yet

- Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) ReferencesDocument195 pagesPersonality Assessment Inventory (PAI) ReferencesShervinT-RadNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Psychodynamic Psychotherapies - An Update (2015) PDFDocument14 pagesThe Effectiveness of Psychodynamic Psychotherapies - An Update (2015) PDFmysticmdNo ratings yet

- What We Have Changed Our Minds About Part 2 BorderDocument12 pagesWhat We Have Changed Our Minds About Part 2 BorderMaría José LamasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document5 pagesChapter 13pairednursingNo ratings yet

- Kernberg & Yeomans (2013)Document23 pagesKernberg & Yeomans (2013)Julián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Borderline Personality Disorder PDFDocument240 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder PDFAngélica100% (1)