Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Walker-CaligariTJ58 4

Uploaded by

Yixuan WOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Walker-CaligariTJ58 4

Uploaded by

Yixuan WCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/236766526

"In the Grip of an Obsession": Delsarte and the Quest for Self-Possession in

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Article in Theatre Journal · December 2006

DOI: 10.1353/tj.2007.0034

CITATIONS READS

2 332

1 author:

Julia A. Walker

Washington University in St. Louis

9 PUBLICATIONS 37 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Julia A. Walker on 28 September 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

"In the Grip of an Obsession": Delsarte and the Quest for Self-Possession in "The Cabinet of

Dr. Caligari"

Author(s): Julia A. Walker

Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 58, No. 4, Film and Theatre (Dec., 2006), pp. 617-631

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25069918 .

Accessed: 29/09/2014 16:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Theatre Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

"In the Grip of an Obsession":

Delsarte and the Quest for Self-Possession

in The Cabinet ofDr. Caligari

Julia A. Walker

Almost from the moment of its 1920 release, the German silent-film classic The Cabinet

of Dr. Caligari has generated interpretations focused on psychological themes. Given

that the film's narrative concerns a showman, Dr. who commands

traveling Caligari,

a control over

the mind of his protege, Cesare, and given that the story it

hypnotic

self is told from the perspective of Francis, a man whose sanity is questioned by the

film's frame narrative, this critical concern with psychological themes is no surprise.

Nor is it a surprise that the psychological model invoked in these critical treatments

is predominantly Freudian. As Catherine Cl?ment observes in her influential 1975

article "Charlatans and Hysterics," Dr. Caligari is the "demoniac double" of Sigmund

Freud.1 Indeed, she in the film's central narrative evoke scenarios

suggests, episodes

recorded in Freud's

Studies inHysteria.1 "Caligari, the film," she argues, "shows in the

huge and magnified forms of expressionism the phantasmic figures of the era inwhich

psychoanalysis could begin."3

That the film engages a Freudian model of the self is irrefutable. But Freud's is not

the only model of self figured in the film. In this article, I argue that The Cabinet of

Dr. Caligari represents a conflict between two models of self: a Freudian self that was

certainly the focus of much discussion if not also anxiety in the moment the film was

made, and an older moral-philosophical model of self that the Freudian model was

in the process of displacing. The film's horror, Imaintain, is focused on that act of

as a clandestine act of murder, or set in

displacement, represented rape, kidnapping,

motion by a criminal mastermind cloaked behind a position of institutional authority.

In that the film represents this character as an unchecked figure of absolute authority,

Siegfried Kracauer is right to read it as an expression of cultural anxiety (even if he

Julia A. Walker is Associate and the Unit for Criticism and at

Professor of English Interpretive Theory

the University Illinois at She is the author and Modernism

of Urbana-Champaign. ?^Expressionism

on the American Bodies, Voices, Words 2005), and is currently at work on a

Stage: (Cambridge,

new book titled and Performance.

project Modernity

1

Catherine B. Cl?ment, "Charlatans and Hysterics," trans. Christiane Reese and Mike Budd in The

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories, ed. Mike Budd (New Brunswick: Rutgers University

Press, 1990), 192.

2

Ibid., 195. Here, she specifically references Cesare's kidnapping of Jane, which recalls patient ac

counts of "nocturnal terrors of stifling bourgeois bedrooms."

3

Ibid., 193.

Theatre Journal 58 (2006) 617-631 ? 2006 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

618 / JuliaA. Walker

is wrong to read it in presciently political terms).4 Insofar as Caligari is a figure for

Freud, the film articulates a fear about the institutionalization of a Freudian model of

self. As several scholars have suggested, the split subjectivity of the Freudian model is

figured allegorically in the Caligari-Cesare dyad. But the moral-philosophical self that

it displaces is also figured allegorically in Francis, Jane, and Alan, the trio of friends

with whom the film asks us to sympathize. In this way, the film represents these two

models of self in conflict within its narrative design.

This conflict, I suggest, also appears in the film's expressionist design, for, in the

flattened perspective of its mise en sc?ne as well as in its camera work, the film en

codes a fear of depth that recapitulates the anxieties about the Freudian unconscious

that are expressed within the narrative. Moreover, the frustrated desire to know the

unconscious and thereby unify the divided self that is thematized in the narrative

may be further seen in the gestural code performed by the film's actors. As we will

see, the repeated gesture of an outstretched, grasping hand becomes a leitmotif for

the quest for self-possession?a quest the film represents both narratively and stylisti

cally as impossible. Since this gestural code, which derives from the acting method

developed by Fran?ois Delsarte, was based on a moral-philosophical model of self,

we may see how this heretofore unacknowledged model of self is formally?as well

as narratively?inscribed into the film. By uncovering this trace of the film's theatrical

legacy, I ultimately hope to show how the film's narrative and expressionistic designs

are in fact integrally, as opposed to merely incidentally, related.

Competing Models of the Self

Patrice Petro has observed that much of the scholarship on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

"reveals a preference for allegorical readings focused largely on the figuration of the

split or multiple self and the terrifying double."5 Indeed, the film easily lends itself to

a Freudian reading wherein the split self of the conscious subject and its unconscious

may be seen in the relationship between Caligari and Cesare as well as that between

Francis and Caligari / Cesare. This doubling, Dietrich Scheunemann points out, actually

derives from the Romantic literary tradition of the Doppelg?nger. In his reading,

Dr. Caligari is a Doppelg?nger, an

offspring of a gothic tale, a late descendant of those split

of nineteenth-century Romantic literature who are haunted their shadows

personalities by

and alter egos, form alliances with forces, create artificial who

dangerous magic beings

escape their control, and usually end in self-destruction.6

eventually

As he notes, this tradition, with its gothic fixation on the supernatural, first appeared

in response to the Enlightenment as a way of questioning a fixed conception of the

self, especially the idea that the self is or can be knowable.7

4

Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari toHitler: A Psychological History of German Film (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1947). Since 1977, when the film's original script was discovered, several scholars

have systematically debunked many of the core assumptions upon which Kracauer's thesis was built.

See, for example, Mike Budd, "The Moments of Caligari," in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Dietrich

Scheunemann, "The Double, the D?cor, and the Framing Device: Once More on Robert Wiene's The

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," in Expressionist Film?New Perspectives, ed. Dietrich Scheunemann (Suffolk, UK:

Camden House, 2003), 127.

5 in The Cabinet

Patrice Petro, "The Woman, The Monster, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," of Dr.

Caligari, 207.

6

Scheunemann, "The Double, the D?cor, and the Framing Device," 130.

7Ibid., 131.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUESTFORSELF-POSSESSION/

DELSARTE 619

One such example of this "knowable" Enlightenment self is the model set forth

by Johann Casper Lavater (1741-1801), an eighteenth-century Swiss theologian and

moral philosopher known for his theory of physiognomy. According to Lavater, the

self was comprised of three "faculties"?reason, sentiment, and will?each of which

resided in a specific realm of the body. Reason, he posited, governed from the head;

sentiment or moral feeling resided in the upper torso, centering upon the heart; and

will dominated the lower torso, commanding the genitals and legs. Although itwas

later contested by Franz Joseph Gall's theory of phrenology, which sought to firmly

relocate these and other so-called faculties within the brain, Lavater's theory was

highly influential, serving as the foundation for the vocal and movement theories of

Fran?ois Delsarte (1811-1871). In his hands, the three faculties of reason, sentiment,

and will became the motive forces behind the body's three "languages" of expression:

verbal, vocal, and pantomimic. Observing patterns in the habits of expression people

used in everyday life, Delsarte purported to discover the natural laws that governed

these three languages, composing a highly elaborate system of

vocality and gesture.

Delsarte, like Lavater (and even Gall), understood the self to be more or less transpar

ent. The problem for each of them was how best to document itsmanifestation in and

through the body.

By 1920, when The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was made, this moral-philosophical model

of the self was being seriously challenged by what Fred Matthews refers to as the "new

psychology."8 As Freud's theories of psychoanalysis became widely disseminated, so

also did a new model of the self, one that postulated an unconscious seat of motiva

tion propelled by instinctual drives. But, as Matthews points out, Freud's theory of

the unconscious did not appear ex nihilo; Freud simply reconceptualized and gave

scientific credibility to an idea?the unconscious?that had been circulating throughout

the nineteenth century.

Indeed, roughly concurrent with the late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century theo

ries of physiognomy and phrenology were Franz Anton Mesmer 's theory of "animal

magnetism" and James Braid's reformulation of it as "hypnotism." Where Mesmer

held that "animal spirits" circulating through one's body could be influenced by the

magnetic force of another person, Braid took that susceptibility of influence as the

focus of his studies. a mesmerist demonstrate his

Seeing traveling magnetic power

by passing over a subject's body and thus putting him or her into a trance,

his hands

Braid realized that, though Mesmer 's theory was wrong, he had discovered a "real

phenomenon" whose physiological cause was the overstimulation of "the nervous

centres in the eyes and their appendages" (which Braid famously effected by dangling

a bright, shiny object eighteen inches in front of the

subject's eyes).9 Upon reaching a

point of exhaustion, the subject entered into a state of consciousness akin to a waking

sleep. Although Braid debunked Mesmer 's theory, the latter's influence persisted in

the terminology used to describe the two parties involved in the hypnotic session: the

or source of the force, and the "medium," the whose

"operator," controlling recipient

8

Fred Matthews, "The New Psychology and American Drama," in 1925, The Cultural Moment, ed.

Adele Heller and Lois Rudnick (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991), 146-56.

9

James Braid, Neurypnology; or, The Rationale of Nervous Sleep, excerpted in Embodied Selves: An

Anthology of Psychological Texts 1830-1890, ed. Jenny Bourne Taylor and Sally Shuttleworth (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1998), 59-61. For a historical and scholarly account of mesmerism and hypnotism,

see Alan Gauld, A Press, 1992).

History of Hypnotism (Cambridge: Cambridge University

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

620 / JuliaA. Walker

body was acted upon by those forces. Once the medium could be induced into a trance

state or "nervous arose over the extent to which the was

sleep," suspicions operator

in control of the medium's will, especially when unscrupulous practitioners and self

styled Svengalis used the technique to take advantage of pliable young women. But

Braid, like Mesmer before and Freud after him, maintained a scientific interest in this

state of half-consciousness, hoping to tap its curative potential for the treatment of

otherwise intractable nervous disorders.

To be sure, Freud's conception of the "unconscious" is a considerable leap from

Mesmer 's "magnetic fluids" or even Braid's "nervous sleep," yet all three point to a

common concern with an aspect or region of the self that is beyond the reach of normal

consciousness. I use the phrase "aspect or region" because late nineteenth- and early

twentieth century theorists did not know

quite what to call it. Freud himself hedges

here, drawing upon metaphors of both geography and action; in outlining his model

of self in the early 1920s, Freud refers to the id, ego, and superego as "provinces or

agencies" of the brain.10 Note that his model, like the moral-philosophical model

before it, is tripartite. Yet, the two are hardly analogous. Freud's model is rooted in

an evolutionary logic, with the id originating in the most primitive area of the brain,

the ego developing in response to environmental demands to regulate its urges, and

the superego a manifestation of the social life of humankind. By introducing this

historical dimension to his understanding of the self, Freud deepened a model that

was otherwise flat. Where Lavater mapped the faculties of reason, sentiment, and will

a

laterally onto the body, Freud introduced three-dimensionality that points to hidden,

and possibly unknowable, depths, leading his popularizers to refer to his approach

as "depth psychology."11

Within the popular imagination, this new model of the self was the subject of great

consternation. That the dominant faculties of reason, sentiment, and will were to be

replaced by the Darwinian notions of id, ego, and superego was troubling enough. But

that this new model of the self was premised upon the existence of a

region beyond

consciousness was cause for alarm. Mesmeric and had

hypnotic suggestion already

shown that this uncharted region was potentially subject to an operator's control; to

maintain, as Freud did, that it lay beyond one's own self-knowledge raised all sorts of

questions concerning moral agency and legal responsibility.

Allegory of the Two Selves

According to Stefan Andriopoulous, such questions stimulated "an intensive medical

and legal debate" in Germany and the scientific community at large between 1885 and

1900.12 At the center of this debate was the hypothetical situation of a medium com

to commit a a

crime while under hypnosis.13 That such medium could be made

pelled

10

Sigmund Freud, An Outline of Psycho-Analysis, trans, and ed. James Strachey (London: W. W.

Norton, 1949), 2.

11

Freud was just beginning to formulate this tripartite model of the self when the film was being

made. Nonetheless, the split subject through which these three "provinces or agencies" operate already

suggested this element of "depth."

12 as an

Stefan Andriopoulous, in Darkness: Hypnosis of Early Cinema,"

"Spellbound Allegory

Germanic Review 77, no. 2 (2002): 102-16.

13 crimes in order to prove

Andriopoulous notes that "numerous physicians staged fictitious hypnotic

their feasibility." As evidence, he quotes the following passage from August Forel:

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUESTFORSELF-POSSESSION/

DELSARTE 621

to forget his or her crime upon waking only exacerbated fears about this hypothetical

situation. As Andriopoulous notes: "The belief in the possibility of perfectly camou

flaged suggestions produced the paranoia that there might be an unlimited number of

unknown hypnotic crimes, which simply could not be recognized as such."14 Tracing

the impact of this medical and legal debate in Germany, Andriopoulous suggests that

it is an important cultural subtext to Caligari, a film that directly engages these debates

by portraying Cesare as the hypnotized subject of Dr. Caligari, the mastermind of his

medium's criminal spree.

But Caligari, of course, is also a showman who seeks a permit to exhibit Cesare as

a sideshow attraction at the local fair. Given the spectacular nature of the mesmeric

session and its invitation to credulity, hypnotism naturally lent itself to the theatre,

where itwas popularly featured in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Framed within its proscenium, hypnotism both thematized and enacted the power of

the theatre itself, showing how the mind is susceptible to outside suggestion and can

even be led to believe that something is real when in fact it is fabricated.15 Hypnotism

thus staged the idea that the human mind was subject to the power of charismatics,

showmen, or worse.

conjurors,

By bracketing this story inside the story of Francis's delusion, the film creates an

endless of as Kracauer and other commentators have well ob

displacement certainty,

served. Indeed, part of what makes the film so frightening is its lack of a resolution.

We don't know whether we have been entranced by Francis's story, induced to believe

(wrongly) that it is true, or to believe in its veracity and recognize our powerlessness

as subjects of Dr. Caligari's control. Who is the operator, and who is the medium? If

Francis is the operator, then we are his dupes; if Caligari is the operator, then we are

his unwilling subjects insofar as we identify with Francis. In either case, the startling

effect of the film comes from the experience of not being in control, and of not recog

nizing that fact until the end.

In Andriopoulous's reading, the film is literally about the fear of hypnotism. Yet, as

the psychoanalytic critical tradition has established, the film also invites ametaphorical

reading in which hypnotism becomes a way of figuring the relationship between the

self and its unconscious. In this reading, Caligari and Cesare (and / or Francis and

Caligari / Cesare) allegorically represent the split subjectivity of the conscious subject

I gave a revolver, loaded with blank bullets by Mister H?felt, to an elderly man, whom I had just hypnotized.

Pointing at H., I explained to the hypnotized person that H. was an evil man, whom he ought to shoot. With

great determination, he picked up the revolver and fired straight at Mister H. Mister H. fell over, simulating

an injured man. I then explained to the hypnotized that the guy was not quite dead yet, he should fire another

shot at him, which he did without hesitation.

remarks that "Forel saw an even

greater danger in so-called

Andriopoulous post-hypnotic suggestions,

which would be enacted after

awaking from hypnosis. to Forel, these post-hypnotic sug

According

gestions would allow for a crime and its execution at a

specific time to be 'implanted/ while creating

the illusion of a 'free-willed decision/" Ibid., 103.

14

Ibid.

15

Anton Kaes has famously that the film thematizes as a self-reflexive meditation

argued hypnotism

on the power of cinema. He specifically to the scene in Caligari's tent where, similar to Francis

points

and Alan, film viewers are summoned into a darkened space to be both transfixed by the image before

them and presented with the spectacle of transfixion; see Anton Kaes, "Film in der Weimarer

Republik:

Motor der Moderne," in Geschichte des deutschen Films, ed. Wolfgang Jacobsen, Anton Kaes, and Hans

Helmut Prinzler (Weimar: J. B. Metzler, 1993), 39-100.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

622 / JuliaA. Walker

and his unconscious self. the conscious the social world of

Caligari, subject, negotiates

the fair at Holstenwall, where bureaucratic order imperfectly regulates the dynamic

energies of social exchange. Cesare, in his perpetual somnambulistic state, represents

Caligari's unconscious, locked deep inside a coffin, yet unleashed at night to act upon

aggressive or libidinal urges under the cover of darkness. He is, in Scheunemann's

formulation, "the personification of Caligari's impulsive drives."16 But, given that it is

Caligari who commands Cesare to act on his behalf, it is also possible to read Cesare

as the conscious subject, appearing to be awake and able to exert his own agency, and

Caligari as the unconscious, compelling the conscious subject to abide by his directives.

After all, we are led to believe that, though Cesare kills the town clerk, murders Alan,

and attempts to stab Jane, he does so at Caligari's behest. In either case, the film seems

to figure the psychological self as a split subjectivity, centering our fear on the possibility

that our agency is not our own, that it could be appropriated by someone (a hypnotist

or mesmeric operator) or something (the unconscious) beyond our control.

And yet, when the frame narrative is added, the allegory expands, suggesting

that Francis is the conscious subject, whose agency is established not only in the act

of narrating the story, but in his role as its hero, seeking justice and truth. When we

discover that his sanity is in question at the end of the film, however, we are inclined

to reassess his story, seeing in the figures of Cesare and Caligari a projection and dis

avowal of his own unconscious desires. After all, we don't see Cesare kill the town

clerk; we arrive at the crime scene after the fact. We don't see Cesare murder

only

Alan; we only witness a shadow of the crime. And, though it is Cesare who abducts

Jane, we know that Francis loves her from an early moment in the film and that he

claims her as his betrothed to his interlocutor at the end. Thus, as Thomas Elsaesser

has pointed out, Francis also has a motive for killing Alan, his rival in love. He also

has amotive for abducting Jane. Since it is his story, we might infer that he substitutes

Cesare for himself when he cannot admit his own desires.17 Indeed, this might explain

what Richard McCormick describes as the most "anarchic" moment in the film, when

Cesare seems "to exceed his as 'tool/ overcome his own desire

identity Caligari's by

for Jane."18 Sent to kill her, he finds himself arrested by her beauty and so abducts her

instead. The sexual connotations are obvious; Cesare cannot her with

penetrate body

his knife and so is rendered Insofar as he acts as Francis's Cesare

impotent. surrogate,

symbolically enacts his sexual frustration.

The frame narrative, then, functions to recapitulate the split subjectivity dramatized

within the central narrative. In both its central and frame narratives, the film focuses

its horror on a Freudian model of the self, which?unlike the unified and knowable

moral-philosophical self?is beyond our ken, beyond our control, and thus beyond

moral accountability.

But the moral-philosophical self also appears in the film. Indeed, we might see

its three faculties of reason, sentiment, and will figured in the three friends, Francis,

Jane, and Alan. Francis represents an Enlightenment configuration of reason, one that

seeks a cause to the events propelling the film's narrative. As Elsaesser has observed,

16 130.

Scheunemann, "The Double, the D?cor, and the Framing Device,"

17 in The Cabinet

Thomas Elsaesser, "Social Mobility and the Fantastic: German Silent Cinema," of

Dr. Caligari, 184.

18 to Dietrich: and Cinematic inWeimar

Richard McCormick, "From Caligari Sexual, Social, Discourses

Film," Signs 18, no. 3 (1993): 649.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUEST FORSELF-POSSESSION/

DELSARTE 623

he is a "detective" figure who searches for the culprit throughout the film.19 Indeed,

as reason, he goes to the police, seeking agents who will act on his beliefs. Jane, as a

woman and the love object of both friends, represents sentiment. Dressed in white,

she is also a figure of moral purity and stands at the center of Francis and Alan's

friendship. And, finally, Alan represents impulsive, perhaps unthinking, will. When

we meet him, he is trying to concentrate on a book but is easily distracted by the ac

tivity outside his window?an intellectual he is not. That he represents the will may

be seen in his appeal to Francis to go to the fair, and in his readiness, while there, to

volunteer as Cesare's

stooge.

The bond uniting the three friends is strong at the beginning of Francis's story, sug

gesting a harmonious relationship among them. This is very much in keeping with late

nineteenth-century appropriations of Lavater's theory such as the Delsarte method.

As I have discussed elsewhere, followers of Delsarte's method emphasized his goal

of attaining harmony (both literal and metaphorical) and articulated it to turn-of-the

twentieth-century fears about modernity.20 In their hands, the Delsarte method became

a means of de-alienation in a moment when new communications

technologies (e.g.,

film, phonograph, typewriter) were splintering the three languages of the body into

isolated bodies, voices, and words. By practicing the Delsarte method, students could

learn to re-coordinate these three languages and so achieve spiritual harmony. The

exercises of Emil as

group-movement Jaques-Dalcroze?known "eurhythmies"?and

the dance-movement exercises of Rudolf von Laban?known as

"eukinetics"?similarly

sought to restore balance and harmony to their practitioners (as suggested by the Greek

prefix "eu," meaning "good"). Thus, the strong bond uniting the three friends at the

beginning of Francis's story suggests a spiritual harmony among them. That harmony,

however, is immediately threatened upon Caligari's arrival inHolstenwall. After they

encounter him at the fair, Francis and Alan part company, reaffirming their friendship

despite their rivalry for Jane's affection. Their friendship, however, is destroyed?not

by jealousy, but by Alan's murder, the news of which Francis at once repels and then

resolves to avenge with justice. When he tells Jane of Alan's death, she too reacts with

horror, but their mutual anger and sadness are not enough to bind them together.

As Francis adamantly expresses his intent to capture the murderer, Jane drifts into a

solipsistic reverie, perhaps grasping onto Alan's memory. The murder dissolves the

bond among the three friends not only through the violent removal of Alan, but by

splitting Francis and Jane apart in their atomized responses to it.

If, as Cl?ment observes, Caligari is Freud, then the film suggests that a stable moral

philosophical model of the self (and the worldview it supported) was destroyed by the

arrival of Freudian psychoanalysis. Indeed, the narrative conflict in the film can thus

be read as occurring between the two primary character groupings?Caligari / Cesare

and Francis / Jane / Alan?and, as such, figures a conflict between these two models of

self. At the time the film was made, the Freudian model was in the ascendant, but that

didn't mean itwasn't also attended by profound cultural anxiety. As Andriopoulous

has noted, much of that anxiety concerned questions of moral responsibility and legal

accountability that were raised by the existence of an unconscious. Itmay be significant

19

Elsaesser, "Social Mobility and the Fantastic," 182. Elsaesser identifies the detective genre as an

important subtext in the film, noting that it was popular in in the early 1920s.

Germany

20

Julia A. Walker, Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words (Cam

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

624 / JuliaA. Walker

then, that, of the three friends, Alan?the of will?is the one who is murdered.

figure

Within the allegorical reading I am proposing, the film suggests that, with the arrival

of the unconscious, the moral and legal agency whose existence is premised upon the

idea of amanifest and accountable will is doomed to die "tomorrow." After all, if one

may be understood to act upon the prompting of drives and instincts that cannot be

known, even to oneself, then how could one be held morally or legally accountable?

The introduction of a Freudian model of the self necessarily meant a wholesale over

haul of cultural attitudes toward moral and legal responsibility.

The implications that such a model held for conventional moral attitudes can be

seen in the film's account of Jane, the figure of sentiment and the moral center of the

three friends. After learning of Alan's death, she is despondent, with all feeling drained

away. When we next see her, she is looking frantically for her father, perhaps searching

for the roots of her emotional life and the source of her moral strength. Wandering

into the fair she finds not her father, but another doctor, Caligari, who, as Elsaesser

points out, is her father's perverse double.21 As with Alan, this encounter will render

her powerless as she flees the threat revealed in Cesare, only to succumb to him later.

if not killed, Jane is nonetheless a casualty in the

Kidnapped, struggle between the

two models of self, suggesting that the unconscious has taken the emotions captive

and disabled their moral base.

The paranoia that suffuses Francis's story would suggest that Caligari and Cesare

are coming for him also. As the last of the three friends and the three faculties within

the moral-philosophical model, he is the last to resist the threat posed by the Freud

ian unconscious. As reason, he seeks to uncover the truth, a that with

quest begins

his resolve to apprehend Alan's murderer. Like the hero in the conventional quest

narrative, Francis as an untested innocent who, a series of

begins through questions

answered and obstacles overcome, passes into a state of knowledge. Although he

finds answers to many of his questions?revealing the criminal in custody to be a

red herring, exposing Caligari's alibi to be a "dummy," and pursuing Caligari to the

asylum where he discovers both his assumed identity and the damning confession in

his journal?Francis is ultimately unable to complete his quest. For, just as he uncovers

the "truth" of the director's mad experiment with the somnambulist Cesare, Francis

himself is revealed to be a thus an unreliable narrator?with the reintro

patient?and

duction of the film's frame narrative. If Francis reason, then, as an inmate

represents

of an insane he reason overthrown. As a he is

asylum, represents quester, ultimately

unable to access the truth he seeks. Within the Freudian allegory this is appropriate,

since the unconscious lies beyond the reach of reason. But, given that the frame nar

rative splits Francis's subjectivity, the film also positions Francis as both the subject

and object of his quest. As reason seeking the unconscious, Francis seeks to unify his

divided self; his is a quest for self-possession.

"In the Grip of an Obsession"

We see this theme of self-possession figured through two recurring images of hands:

a single hand outstretched in a frustrated grasp, and two hands coming together in

a gesture of incomplete possession. These are Delsartean gestures, enacted by the

to a "convulsive" or "execrative" state in the first instance, and an

performers signify

21

Elsaesser, "Social Mobility and the Fantastic," 185.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUESTFORSELF-POSSESSION/

DELSARTE 625

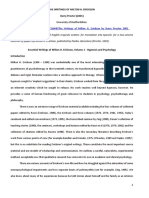

Attitude EX-con Attitude NOR-con Attitude CON-con

Convulsive state Strife, conflict

Authority

Attitude EX-nor Attitude NOR-nor Attitude CON-nor

Normal, relaxed Prostration

Expansion

Attitude EX-ex Attitude NOR-ex Attitude CON-ex

Exaltation Execration

Exasperation

1. Delsarte's "Criterion of the Hands," from Ted Shawn, Every Little Movement: A Book about

Figure

Fran?ois Delsarte (1954; repr., New York: Ted Shawn, 1963).

state in the second. As we have seen, the Delsarte method drew

"expansive" directly

and its moral-philosophical modelof the

upon Lavater's theory of physiognomy

self.22 Accordingly, it divided the into three zones, each of which corresponds to

body

a dominant reason, sentiment, and will. But, in Delsarte's schema, these three

faculty:

zones into three zones, each of which

are further divided is subject to three types of

movement?concentric, normal, and eccentric?allowing for a highly differentiated

movement and As to be the three types of movement are

range of meaning. expected,

each governed by one of the three primary faculties of the self. Concentric energies

are focused inward and reveal a predominantly mental attitude; normal energies are

22 followed Lavater remains in question. Some of Delsarte's fol

The extent to which Delsarte exactly

lowers divided the body into head, upper torso, and lower torso as did Lavater, but most divided the

into head torso (sentiment), and limbs (will); see, for example, the writings collected in

body (reason),

Fran?ois Delsarte et al., The Delsarte System of Oratory, 4th ed. (New York: Edgar S. Werner, 1893). For

the best of the Delsarte method one who was trained in it), see Ted Shawn, Every Little

analysis (by

Movement: A Book about Fran?ois Delsarte (1954; repr., New York: Ted Shawn, 1963).

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

626 / JuliaA. Walker

in balance, a moral and eccentric ener

perfect suggesting predominantly disposition;

gies move outward toward the world, revealing a predominantly willful temperament.

Thus, gestures such as the convulsive / execrative hand movements in figure 1 reflect

a tension between "concentric" and "eccentric" energies, suggesting an internal conflict

between thought and will that reveals frustration, while the expansive gesture (which is

akin to the "exaltative" gesture) ismotivated out of a tension between "eccentric" and

"normal" energies, suggesting a desire for emotional satisfaction or moral stability.

These gestures recur at several key moments in the film: when Caligari seeks a per

mit he must wait to obtain; when Cesare awakens; when Alan fends off his murderer;

when Alan helplessly repels his murderer in shadow; when Francis learns of Alan's

death; when Francis reflects upon the significance of Alan's death; when Francis seeks

to apprehend the killer at the police station; when Jane grasps the finality of Alan's

death; when Francis imagines Caligari "in the grip of an obsession"; and when Francis

reaches for Jane at the end, only to see her pass him by, oblivious to his desires (see

figs. 2-11). The repetition of the convulsive / execrative gesture suggests a frustrated

desire to assert or preserve oneself. Given that the film is part of the horror genre, in

which muchof the action concerns real and threatened assaults upon the self, such

gestures?and their meanings?would seem to be appropriate. The repetition of the

"expansive" hand motif, on the other hand, is more unexpected; it indicates one of

two concerns: when used single-handedly, it suggests a vaguely intuited desire; when

used double-handedly in a grasping gesture, it suggests a desire to possess something

more definite. Considering that the film is also a psychological allegory, this double

handed movement may be read as a gesture of se//-possession when we remember that

it is Francis's story and that what he seeks throughout is a reconsolidation of his split

a reconciliation of his conscious self with his unconscious desires.

subject,

This analysis presumes a naturalistic ideal; that is, it assumes that these gestures are

a

used in fairly straightforward manner to communicate the meanings that, according

to Delsarte, they "naturally" signified. Indeed, the Delsarte method was so influential

and so well known at the turn of the twentieth century that significant portions of the

audience could have been expected to easily decipher the meanings of its gestures.

As Mikhail Yampolsky has suggested, it was the basis of Sergei Eisenstein's theory

of montage,23 and no doubt served as a founding principle of the idea that silent film

could speak across cultures through the universal language of images. But the repeti

tion, if not also the exaggeration, of these gestures suggests that they might have been

for other, "expressionistic," purposes.

deployed perhaps

In his groundbreaking study of German expressionist theatre, David F. Kuhns ap

proaches his topic from the perspective of performance, providing extensive cultural

and historical background to the three types of expressionist acting, "Schrei," "Geist,"

and "Ich," first described by Mel Gordon.24 In his discussion of "Schrei" acting, for

example, Kuhns analyzes the impact Frank Wedekind had on the nascent movement

not only as a playwright, but as a performer of his own work. He cites the remarks

23 of the Actor," in Silent

Mikhail Yampolsky, "Kuleshov's Experiments and the New Anthropology

Film, ed. Richard Abel (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 45-67.

24 Uni

David F. Kuhns, German Expressionist Theatre: The Actor and the Stage (Cambridge: Cambridge

Press, 1997). Mel Gordon, Texts," in Expressionist Texts, ed. Mel Gordon (New

versity "Expressionist

York: PAJ Books, 1986). Kuhns, however, rechristens Gordon's third model, referring to the "Ich" style

as "emblematic."

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DELSARTE

AND THEQUEST FORSELF-POSSESSION / 627

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

628 / JuliaA. Walker

Figures 2-11. From

left to right, top to bottom: (2) Dr. Caligari in the town clerk's office. The hand

opens and in a closes

frustrated of his cane, his frustrated grasp of power.

grip symbolizing

(3) Cesare awakens. The somnambulist's arms rise and his hands open in a gesture of possession.

Insofar as he is the "conscious subject" in the Freudian model of self, he is possessed by unconscious

forces. Insofar as he is the "unconscious," he wishes to possess his desires, etc.

(4) Alan fends off his murderer. convulsive or execrative Alan's hands feature in an

Signifying feelings,

Eisensteinian montage sequence. (5) The Shadow of Death. Alan succumbs to his murderer as painted

both reveals and conceals the crime scene. 6) Francis learns of Alan's death. Note the of

light gesture

repulsion. (7) Francis reflects upon the significance of Alan's death. Does he wish to possess Alan's

murderer or Jane? 8) Francis goes to the station. As "reason" within the moral-philosophical

police

model of self, he seeks agents who will act upon his beliefs. (9) Jane learns of Alan's murder. After

expressing her horror at his death, she possesses tender of him in her memory. (10) "In the

thoughts

an obsession." In Francis's grasps at the secrets of the original Dr.

grip of imagination, the director

Caligari. (11) Francis sees Jane. Having concluded his story, Francis spies his "fiancee," from across the

yard at the asylum. Although he is not self-possessed, he nonetheless is revealed to possess "feelings"

(i.e., Jane, within the moral-philosophical schema) that he could not previously admit.

Stills captured from the restored version of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, originally produced

by Decla Film Gesellschaft, Berlin.

of several contemporary observers who sought to describe the curious appeal of

Wedekind's charismatic performance style. Of his staged readings, Artur Holitscher

singled out his

extraordinary

art of accentuation [Betonung], which later as an actor of his own pieces,

[hej developed to a mastery. It was a to listen to Wedekind. When he

special pleasure

read he was in love, one might almost say, with each of his words. With voluptuous joy

a creation out of a vowel and consonant.

he fashioned He willed \fiigte] sentences into

the manifest of a harmonious

fullness form. In these readings, his dialogue achieved, and

his characters

received, a contour and depth as never did on the stage. . . .

they Through

an retardation of tempo, a before or after a word, what he said

imperceptible tiny pause

took on a meaning which could sooner be apprehended than intellectually. . . .

intuitively

While he read he appeared to be certain of the effect of each of his words and

completely

of every detail of his poetic art.25

Although Kuhns doesn't identify it as such, what Holitscher describes is a Delsartean

or to oral In to his vowels and

"expression-ist" approach interpretation.26 attending

consonants in such a as to evoke a "manifest fullness of a harmonious form,"

way

25

Quoted in Kuhns, German Expressionist Theatre, 48.

26

Kuhns does not mention the Delsarte method as an influence on he does

Although expressionism,

cite the movement work of Dalcroze, von Laban, and Isadora Duncan, all of whom were influenced by

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUESTFORSELF-POSSESSION /

DELSARTE 629

Wedekind was in effect practicing the Delsartean aesthetic in using tempo and silence

to heighten the expressive powers of his words such that a listener could intuit their

meaning before he or she registered their significance intellectually.

Kuhns cites numerous others whose accounts of Wedekind's performance style

similarly attest to a Delsartean influence.27 Yet, nearly all of these commentators also

remark upon the "shrill" or "sharp" tonality Wedekind used and the "awkwardness"

of his gestures, which, like his vocal style, was strangely moving. Such terms suggest

that Wedekind's performance style, though perhaps derived from Delsarte, was not,

finally, Delsartean in the sense that it did not aim at creating a truly harmonious ef

fect. Rather, it appears to have drawn upon Delsarte's insights into the formal power

of voice and gesture to create meaning, while redirecting his techniques toward the

meaningful expression of disquieting?rather than beauteous?subject matter. In other

words, itwould appear that Wedekind stretched and distorted Delsarte's techniques

beyond Delsarte's original intent in order to represent verbally, vocally, and panto

mimically the modernist alienation and spiritual suffering of his characters. In doing

so, Wedekind developed the Schrei style of expressionist acting.

Among the actors directly influenced by Wedekind was Werner Krauss, who plays

Dr. Caligari in the film. As a member of Max Reinhardt's troupe, Krauss worked with

Wedekind during the 1913-1914 season when Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater staged

several ofWedekind's early plays.28 Although he had no formal training, Krauss became

an exemplary expressionist actor, incarnating the roles of Schigolch in Wedekind's

Erdgeist, Launhart in his Hidalla, Professor D?hring in Der Stein derWeisen, and Konsul

Kasimir inMarquis von Keith; he also played the fourth sailor in Reinhard Goering's

expressionistic Seeschlacht.29 Of his performance in this last role, Herbert Ihering re

marked that, for Krauss, "the word was not accompanied by gesture, not amplified

by movement: the word was gesture, the word became flesh. ... It [was] as though

he saw sounds and heard gestures."30 Kuhns concludes that "[i]t was precisely this

absorption of sound into sight in the Schrei acting of Werner Krauss that enabled him,

as [Julius] Bab said, to be 'one of the few in Germany [at that time] who [could be]

creative in the cinema.'"31

truly

Although the "excess" of the acting in Caligari might, from the distance of our his

torical moment, seem indistinguishable from that of early silent-film acting in general,

I believe that it is an example of the ironic appropriation of the Delsarte method that

came to be associated with what Kuhns describes as the Schrei style of expression

ism. Certainly, Delsartean gestures appear repeatedly throughout this film (and I have

Delsarte's work. Kuhns identifies von Laban's and "peripheral" as part

explicitly "centripetal" gestures

are

of the Schrei style of expressionist acting, noting that these gestures clearly evident in The Cabinet of

Dr. Caligari (Kuhns 71). Apropos toWedekind's

possible exposure to the Delsarte method, Kuhns has

established that the playwright / performer spent considerable time in Paris during the 1890s (54).

27Ibid., 45-51.

28

Conrad Veidt, who plays Cesare, and Lil Dagover, who plays Jane, were also members of Reinhardts

Lotte Eisner identifies Veidt as one of Reinhardt's actors, in her work, The Haunted Screen: Ex

troupe;

pressionism and the German Cinema and the Influence ofMax Reinhardt of California

(Berkeley: University

Press, 1965), 44; and J. L. Styan includes a of Dagover in a Reinhardt in his

photograph production,

book, Max Reinhardt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 105.

29

Kuhns, German Expressionist Theatre, 106-7.

30

Quoted in Kuhns, ibid., 107.

31

Ibid., 108.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

630 / JuliaA. Walker

isolated only two or three significant motives involving the hand). That they are exag

gerated in a way that would have allowed audiences to recognize them as such may

be debatable, but it certainly accords with the interpretation I have laid out above.

Insofar as the film is about a contest between a residual moral-philosophical model of

the self and an emergent Freudian model of the self, such exaggeration would suggest

that the older model of self was, like the gestures used to signify it, under duress and

strained to the point of exhaustion.

If the crisis of the moral-philosophical model of self is encoded formally in the film's

acting, the threat posed to it by a Freudian, or "depth," model of the self is encoded

in the film's mise en sc?ne. Indeed, the fear of and desire to penetrate the depths of

the unconscious is figured not only narratively in Francis's quest, but formally in the

film's expressionistic scenic design where a dialectic of flatness and depth is presented

visually. As has been much discussed, the film renders three-dimensional space in a

stylized manner, with light and shadow painted onto walls, floors, and ceilings, and

the diminishing point of the horizon suggested by the skewed lines of awindow frame

or door. Such stylization is not merely incidental, as scholars such as Scheunemann

have claimed, nor was it simply the result of commercial opportunism, as Mike Budd

and Barry Salt have asserted; rather, it is integral to the film's thematic concern with

psychological depth and the Freudian unconscious.32 By flattening its scenic perspec

tive, the film encodes the very fear of depth that propels its narrative action. Moreover,

it secures (and perhaps overdetermines) our sympathetic identification with the trio

of friends who represent a "flat" model of the self. Through that identification and

through the shallow space in which the camera virtually moves us, we experience the

twinned desire for and fear of penetrating the hidden depths of the unconscious.

We can see that movement of penetration and the camera

repulsion replicated by

work. In the tent scene, for example, Caligari, having obtained his permit, invites us,

along with Francis and Alan and the assembled crowd, inside to view his exhibit.

First he lifts the flap and beckons us in, then he draws the curtain, and finally opens

the coffin to disclose Cesare. In a series of shots ranging from a long shot of the tent

interior to amedium shot of Caligari and Cesare onstage to a close-up of Cesare (with

a reaction shot of Caligari cut into the sequence), the camera moves us through these

various into the of the tent. When we see Cesare awaken, we are invited

layers depths

to consider that there is a deeper layer to penetrate?his mind?yet, asMichael Minden

observes, "no revelation of takes Instead, we are

magical inferiority place."33 repelled

by his hideous zombie-like gaze. When Cesare speaks?to predict Alan's imminent

death?we are transfixed with fear, not only because we react with Alan to such hor

rible news, but because the fact that Cesare speaks means that this seeming puppet has

a mind and thoughts of his own. The sensation of horror that we experience vicari

ously is effected visually by the frantic montage of close-ups?from Alan to Cesare to

Alan again and then to Francis?that punctuates a scene of medium shots of relatively

32

Scheunemann, "The Double, the D?cor, and the Framing Device," 138; Budd, "The Moments of

26; Salt, "From German Stage to German Screen," in Prima di Caligari: cinema tedesco,

Caligari, Barry

1985-1920 I Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli

(Pordenone, Italy: Edizioni Biblioteca dellTmmagine, 1990), 406.

33

Michael Minden, "Politics and the Silent Cinema: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Battleship Potemkin,"

in Visions and Blueprints: Avant-garde Culture and Radical Politics in Early Twentieth-century Europe, ed.

Edward Timms and Peter Collier (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), 293.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AND THEQUESTFORSELF-POSSESSION/

DELSARTE 631

long duration. As Minden notes, "[Cesare's] blank face functions as a block to [our]

eagerness for ever more intimate disclosure,"34 masking the unplumbable depths from

which his words arise. We are fascinated by Cesare yet repelled by him?an action

replicated by the camera as it follows the series of intercut close-ups with a long shot

of the tent's interior that places us against its rear wall.

This movement of penetration and repulsion occurs again in the bedroom scene,

where Cesare comes to murder Jane. Here the camerawork is The scene

again, important.

begins with a long shot of Jane's bedroom, with Jane in bed asleep in the foreground. In

the background is a large window surrounded by decorative embellishments that look

like daggers. Inwhat seems to be a jump cut, Cesare appears at the window, looking in.

From this long shot, our view is immediately foreclosed by a diamond iris that focuses

our attention on Cesare while maintaining a perspective of distance. Framed by the iris,

Cesare rises menacingly from his crouched position. The camera cuts to another long

view of the room, quickly followed by a shot of Cesare?again framed by the diamond

iris?with knife in phallic position, pushing the broken window frame out of his way

and stepping into the room. In a long shot of very long duration, Cesare slowly crosses

the room, approaching the sleeping Jane in her bed. He raises his knife to kill her, but

stops inmid-action, arrested by her beauty. In a series of quick cuts ranging from full

view to close-up, Jane awakens and struggles with Cesare. As with the tent scene, we

experience the horror of the encounter vicariously by the fast-paced rhythm of the

montage. Here, though, the attempted penetration?and repulsion?is effected visually

through the alternating perspective of full view to close-up; it is almost as if the knife

moves toward us, then out, then in again, and out. With a quick cut to Jane's father and

brother, who are awakened her screams, the camera shifts once more

presumably by

to a long view of the room that Cesare crosses and exits, moving from foreground to

background, with Jane in his arms. In this scene, we stand in a different relationship

to the movements of penetration and repulsion than in the earlier scene. Where, in the

tent scene, the camera moved us toward Cesare?the unconscious?and the of

object

our penetration, here it positions us firmly in the foreground and

aligned with Jane,

whose white-clad innocence and vulnerability is our own, as Cesare penetrates the space

of the room in a threatening movement toward us. What such camerawork suggests

is that, though the unconscious itself may be impenetrable, we are not invulnerable

to the threat that it?and the Freudian model of self?represents.

Thus, we see that, when read as an allegory of two competing models of self, the

film appears to cohere as an aesthetic whole (albeit one comprised of conflicts and

contradictions). In terms of its narrative, the of a

displacement moral-philosophical

model by a Freudian one is figured in the three friends who are broken apart by a

mysterious traveling doctor and his somnambulistic minion. In terms of its formal

design, a dialectic of flatness and depth functions to encode and enact a fear of the

unconscious in the acting, scenic design, and camerawork. Although scholars long have

puzzled over seeming incongruities such as the "realistic" acting and the stylized set,

or the asymmetrical aesthetic of realism and expressionism in the frame narrative, such

problems are potentially resolved by reconsidering the rich theatrical legacy behind

the film's expressionistic style.

34

Ibid.

This content downloaded from 128.252.110.41 on Mon, 29 Sep 2014 16:18:20 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

View publication stats

You might also like

- Delsarte and CaligariDocument16 pagesDelsarte and CaligariLenz21No ratings yet

- Becoming Alien: The Beginning and End of Evil in Science Fiction's Most Idiosyncratic Film FranchiseFrom EverandBecoming Alien: The Beginning and End of Evil in Science Fiction's Most Idiosyncratic Film FranchiseNo ratings yet

- Women in PossessionDocument40 pagesWomen in PossessionLisa KingNo ratings yet

- Feminism and Dialogics: Charlotte Perkins, Meridel Le Sueur, Mikhail M. BakhtinFrom EverandFeminism and Dialogics: Charlotte Perkins, Meridel Le Sueur, Mikhail M. BakhtinNo ratings yet

- 1982 - Modleski - Film Theory's DetourDocument8 pages1982 - Modleski - Film Theory's DetourdomlashNo ratings yet

- Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and FilmFrom EverandCreaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and FilmNo ratings yet

- Genre Essay RevisionDocument6 pagesGenre Essay Revisionapi-640451375No ratings yet

- Dunavan Dustin Hist 499 Term Paper Rough DraftDocument24 pagesDunavan Dustin Hist 499 Term Paper Rough Draftapi-456562482No ratings yet

- Feminist Film Theory and CriticismDocument21 pagesFeminist Film Theory and CriticismKlykkeNo ratings yet

- Nightmare and The Horror Film: The Symbolic Biology of Fantastic Beings - by Noel Carroll Film Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 3. (Spring, 1981), Pp. 16-25.Document19 pagesNightmare and The Horror Film: The Symbolic Biology of Fantastic Beings - by Noel Carroll Film Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 3. (Spring, 1981), Pp. 16-25.natrubuclathrmacom100% (1)

- The Feminine Sublime in 21st Century Surrealist CinemaDocument95 pagesThe Feminine Sublime in 21st Century Surrealist CinemaMelisaNo ratings yet

- Monsters and Monstrosity in 21st-Century Film and TelevisionFrom EverandMonsters and Monstrosity in 21st-Century Film and TelevisionNo ratings yet

- The Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular ImaginationFrom EverandThe Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular ImaginationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Women and Horror PaperDocument18 pagesWomen and Horror Paperriya.2021.212No ratings yet

- The Horror The HorrorDocument9 pagesThe Horror The HorrorJuani RoldánNo ratings yet

- Nightmare and The Horror FilmDocument11 pagesNightmare and The Horror FilmEMLNo ratings yet

- Scenes of Sympathy: Identity and Representation in Victorian FictionFrom EverandScenes of Sympathy: Identity and Representation in Victorian FictionNo ratings yet

- Biderman MythmakingDocument5 pagesBiderman MythmakingiroirofilmsNo ratings yet

- Horror and the Holy: Wisdom-Teachings of the Monster TaleFrom EverandHorror and the Holy: Wisdom-Teachings of the Monster TaleRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Some Clinical Consequences of Introjection - GaslightingDocument12 pagesSome Clinical Consequences of Introjection - GaslightingGary FreedmanNo ratings yet

- Gardens of Fear: The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Vol. 6From EverandGardens of Fear: The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Vol. 6No ratings yet

- W6-Mythological and Archetypal AppraochesDocument24 pagesW6-Mythological and Archetypal AppraochesJoyce GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Paragraph One: History of HorrorDocument4 pagesParagraph One: History of HorrorPhil GommNo ratings yet

- Shilina-Conte, 'Lessons of Darkness'Document30 pagesShilina-Conte, 'Lessons of Darkness'Elizabeth GarciaNo ratings yet

- Some Clinical Consequences of IntrojectiDocument12 pagesSome Clinical Consequences of IntrojectirzrultNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal SampleDocument9 pagesResearch Proposal SampleHarzelli MeriemNo ratings yet

- Epilogue: Done? Even When Such Seeds Were Not Sown ThroughDocument5 pagesEpilogue: Done? Even When Such Seeds Were Not Sown ThroughCalibán CatrileoNo ratings yet

- Zom DisabilityDocument25 pagesZom DisabilityMark ZlomislicNo ratings yet

- Redeeming Levinas - Borderlands 2010Document8 pagesRedeeming Levinas - Borderlands 2010jd_macreadyNo ratings yet

- The Architecture of Cinematic Spaces: by InteriorsFrom EverandThe Architecture of Cinematic Spaces: by InteriorsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Horror Research Paper TopicsDocument5 pagesHorror Research Paper Topicsuyqzyprhf100% (1)

- Philosophy The MatrixDocument192 pagesPhilosophy The Matrixthorn13100% (1)

- Masculinity and Monstrosity: Characterization and Identification in The Slasher FilmDocument23 pagesMasculinity and Monstrosity: Characterization and Identification in The Slasher FilmNisa Purnama IeChaNo ratings yet

- Beyond Psychoanalysis Post Millennial Horror Film and Affect TheoryDocument20 pagesBeyond Psychoanalysis Post Millennial Horror Film and Affect TheoryПолина ВойцукNo ratings yet

- Abjection - The Theory and The MomentDocument37 pagesAbjection - The Theory and The MomentSoraya Vasconcelos100% (1)

- Off With Her Head The Denial of Womens Identity in Myth Religion and Culture by Howard Eilberg Schwartz and Wendy DonigerDocument7 pagesOff With Her Head The Denial of Womens Identity in Myth Religion and Culture by Howard Eilberg Schwartz and Wendy DonigerAtmavidya1008No ratings yet

- The Rhetoric of Race: Toward a Revolutionary Construction of Black IdentityFrom EverandThe Rhetoric of Race: Toward a Revolutionary Construction of Black IdentityNo ratings yet

- Before Reproduction: The Distortion of Generation: # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007Document14 pagesBefore Reproduction: The Distortion of Generation: # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007Rifqi Khairul AnamNo ratings yet

- Horror Film & Psychoanalysis: Our Fascination With FrightDocument30 pagesHorror Film & Psychoanalysis: Our Fascination With FrightGayle O'Brien100% (2)

- An Examination of Halloween Literature and Its Effect On The Horror GenreDocument69 pagesAn Examination of Halloween Literature and Its Effect On The Horror GenreJuani RoldánNo ratings yet

- Where Film Meets Philosophy: Godard, Resnais, and Experiments in Cinematic ThinkingFrom EverandWhere Film Meets Philosophy: Godard, Resnais, and Experiments in Cinematic ThinkingNo ratings yet

- Dracula and New Horror TheoryDocument13 pagesDracula and New Horror TheoryLunaNo ratings yet

- Alien Thoughts: Mind Reading and Spectatorial PleasureDocument50 pagesAlien Thoughts: Mind Reading and Spectatorial PleasureSteven SchoferNo ratings yet

- Somnambulism, Sleepwalking and Secrets in Victorian LiteratureFrom EverandSomnambulism, Sleepwalking and Secrets in Victorian LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Hanscomb, S. Sartre Studies International: (2010) Existentialism and Art-Horror., 16 (1) - Pp. 1-23. ISSN 1357-1559Document18 pagesHanscomb, S. Sartre Studies International: (2010) Existentialism and Art-Horror., 16 (1) - Pp. 1-23. ISSN 1357-1559Hoorain PariNo ratings yet

- Kuji Kiri StudyDocument25 pagesKuji Kiri StudyTim LuijpenNo ratings yet

- Hypnoanalysis Vol1Document241 pagesHypnoanalysis Vol1brice lemaire0% (1)

- 3fold-Smoking Brochure Version 2Document2 pages3fold-Smoking Brochure Version 2Jane NashNo ratings yet

- How The Brain Power Wins SucessDocument19 pagesHow The Brain Power Wins Sucessvathee_014309No ratings yet

- Yapko Hypnosis DepressionDocument3 pagesYapko Hypnosis Depression11111No ratings yet

- Contraindications and Dangers of HypnosisDocument3 pagesContraindications and Dangers of HypnosisTI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Hist Research ProposalDocument11 pagesHist Research ProposalGregory Steven EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Abreactions PDFDocument7 pagesAbreactions PDFSanty GonzalezNo ratings yet

- SPR Journal v1 n1 Feb 1884Document16 pagesSPR Journal v1 n1 Feb 1884Lariel2No ratings yet

- Click Here To Have The Mind of A Millionaire TodayDocument10 pagesClick Here To Have The Mind of A Millionaire TodayJamesNo ratings yet

- How TV Influences Your Mind Through HypnosisDocument4 pagesHow TV Influences Your Mind Through HypnosiswoodiiisNo ratings yet

- Hypnotic Phenomena and Altered States of ConsciousnessDocument55 pagesHypnotic Phenomena and Altered States of ConsciousnessEd SewardNo ratings yet

- NSA Mind Control Psyops by Will FilerDocument16 pagesNSA Mind Control Psyops by Will FilerAsim AzizNo ratings yet

- Communicating With The SubconsciousDocument7 pagesCommunicating With The Subconsciousjaydeepgoswami5180No ratings yet

- ThesispaperDocument12 pagesThesispaperapi-319669180No ratings yet

- Auguste Rodin - Tragic - PassionDocument23 pagesAuguste Rodin - Tragic - PassionDimitra XaxaxouxaNo ratings yet

- Reinin's BookDocument136 pagesReinin's BookSisyphus17No ratings yet

- HBTM CompressedDocument37 pagesHBTM CompressedEduardo Mendes0% (1)

- Reprogramming Your Subconscious Mind PDFDocument12 pagesReprogramming Your Subconscious Mind PDFGODEANU FLORIN91% (22)

- PTE SummariesDocument2,108 pagesPTE SummariesVenugopal Athiur Ramachandran65% (40)

- Mentalism Rev 4 - FinalDocument47 pagesMentalism Rev 4 - FinalRahul Salim86% (7)

- Three Minds and Three Levels of ConsciousnessDocument4 pagesThree Minds and Three Levels of Consciousnessfpaiva100% (1)

- The Writings of Milton H. Erickson by Ha PDFDocument16 pagesThe Writings of Milton H. Erickson by Ha PDFDaria SotantoNo ratings yet

- HypnosisDocument18 pagesHypnosisapi-26413035No ratings yet

- Secrets of Self - Zap Video ManualDocument22 pagesSecrets of Self - Zap Video Manualrazvicostea100% (1)

- Hypnosis Script For Fear of CriticismDocument3 pagesHypnosis Script For Fear of Criticismraamon9383No ratings yet

- Charles TebbettsDocument5 pagesCharles TebbettsAshvin Waghmare50% (2)

- Covert Hypnosis Language Patterns PDFDocument4 pagesCovert Hypnosis Language Patterns PDFjoko susiloNo ratings yet

- Defining HypnosisDocument6 pagesDefining HypnosisblackvenumNo ratings yet

- Ernest Abraham Hart - Hypnotism Mesmerism and The New Witchcraft Cd6 Id 1860914947 Size232Document73 pagesErnest Abraham Hart - Hypnotism Mesmerism and The New Witchcraft Cd6 Id 1860914947 Size232Dustin Shiozaki100% (3)