Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Food Expenditures and Economic Well Being in Early Modern England

Uploaded by

EloisaOTOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Food Expenditures and Economic Well Being in Early Modern England

Uploaded by

EloisaOTCopyright:

Available Formats

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-

Being in Early Modern England

CAROLE SHAMMAS

The proportion of a household's budget spent on diet has commonly served as an

important measure of material welfare. This paper pulls together data concerning

trends in food expenditures for early modern England and draws comparisons

with figures for later periods. The usefulness of wage assessments, a new source

for estimating the proportion of outlays devoted to diet, is examined. The impact

on food expenditures of new commodities and other dietary shifts is also

explored. The findings call into question earlier estimates of the proportion of

total expenditure devoted to food and drink in the pre-industrial period and the

assumption that food expenditures are always inelastic.

T HE proportion of a household budget devoted to diet has common-

ly served as an important measure of material welfare. According

to "Engel's Law," named after Ernst Engel, a nineteenth-century

pioneer in budget studies, as total family expenditure rises the percent-

age given over to food purchases should decline.1 Households in most

post-industrial countries spend between one-fifth and one-third of their

disposable income on diet. It is assumed that the percentages for early

modern societies were much higher. One frequently cited work shows

English families from the fifteenth century to World War I consistently

allocating 80 percent of their budget to diet.2 Food percentages also

have an impact on other measures of economic well-being because they

are used to weight the basket of consumables in cost of living indices.

The index for England 1264-1954, based upon the above-mentioned

weights, shows real wages not regaining late fifteenth-century levels

Journal of Economic History, Vol. XLIII, No. 1 (March 1983). © The Economic History

Association. All rights reserved. ISSN 0022-0507.

The author is Associate Professor of History, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee,

Wisconsin 53201.

1

On Engel studies see George J. Stigler, "The Early History of Empirical Studies of Consumer

Behavior," Journal of Political Economy, 42 (April 1954), 95-113; Jeffrey G. Williamson,

"Consumer Behavior in the Nineteenth Century: Carroll D. Wright's Massachusetts Worker in

1875," Explorations in Entrepreneurial History, 4 (Winter 1967), 98-135; and more recently,

Steven Dubnoff, "A Method for Estimating the Economic Welfare of American Families of any

Composition: 1860-1909," Historical Methods, 13 (Summer 1980), 171-80.

2

E. H. Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins, "Seven Centuries of the Prices of Consumables,

Compared with Builders' Wage-Rates," in Essays in Economic History, vol. 2, edited by E. M.

Carus-Wilson (New York, 1962), pp. 179-96. A new version of the Phelps-Brown and Hopkins

figures for 1500-1911 appears in E. A. Wrigley and R. S. Schofield, The Population History of

England 1541-1871 (London, 1981), pp. 638-44, but the weights remain the same. The other two

weighted indices covering long periods of time, those of Gilboy and Tucker, use percentages for

diet of 80 percent and 75 percent respectively. See their articles reprinted in The Standard of Living

in Britain in the Industrial Revolution, edited by Arthur J. Taylor (London, 1975), pp. 1-35.

89

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

90 Shammas

until the 1880s! Looking at these figures, a reader might well conclude

that little of importance happened in terms of food consumption until

well after industrialization.

On the other hand, we know from demographic research that by the

mid-seventeenth century starvation-related mortality crises disappeared

in all regions of England and that by the early eighteenth century no

relationship (or only a negative one) remained between grain prices and

mortality.3 Furthermore, the early modern period was the time when, it

is generally acknowledged, non-European commodities—potatoes,

rice, maize, tea, coffee, chocolate, sugar, and tobacco—became en-

sconced in the English diet.4 These developments suggest a time of

great change in consumption levels and eating habits.

The purpose of this short paper is to pull together data concerning

trends in food expenditures for early modern England and draw

comparisons with figures for later periods. The usefulness of wage

assessments, a new source for estimating the proportion of outlays

devoted to diet, will be examined. The impact on food expenditures of

the new commodities and other dietary shifts will also be explored.

While there are many problems involved in trying to estimate food

expenditures in a predominantly agricultural society, a large number of

people in rural as well as urban England in this period depended

primarily on wages for their livelihood and purchased the bulk of their

diet on the market. More than any other group, these wage laborers will

be focused upon here.

Statisticians did not begin conducting budget surveys in a systematic

fashion until the later nineteenth century, but a few contemporaries on

the scene during the early modern period made computations and even

circulated questionnaires about the spending patterns of the laboring

classes that invite comparisons with modern household budget data.

Table 1 shows the percentage of household expenditure devoted to diet

at 13 different points in time from 1695 to 1978. The first column of

percentages is for all households in the survey while the second column

is for that category of household having the lowest income in each

survey. The first figures, those for 1695, are from estimates made by

Gregory King. The next five surveys were inquiries conducted on a

3

Andrew B. Appleby, "Grain Prices and Subsistence Crises in England and France, 1590—

1740," this Journal, 39 (Dec. 1979), p. 867; and Wrigley and Schofield, Population History, pp.

371-72, 399. Appleby, "Grain Prices," p. 882, mentions that the "only likely candidate" for being

an exception to the generalization is a group of Midlands parishes between 1727 and 1730.

4

See Femand Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life (London, 1981), chaps. 2 and 3; and

Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the

European World Economy 1600-1750 (New York, 1980), p. 258ff.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-Being 91

TABLE 1

PERCENTAGE O F ENGLISH HOUSEHOLD EXPENDITURE

DEVOTED TO DIET

(1695-1978)

Poorest

All Category of

Year Household Groups Covered Number Households Household

1695 All English families n.a. 60.7% 74.1%

1787-93 English agricultural laborers 127 72.2 70.1

1794-% English agricultural and urban laborers 86 74.3 69.0

1836 Manchester working class 19 55.0 —

1841 Manchester working class 19 69.3 —

1837-38 English agricultural laborers 54 72.2 —

1890-91 "Normal" British industrial families 455 48.8 50.1

1904 United Kingdom working class 1,944 61.0 67.0

1929 Merseyside working class 154 47.0 50.6

1937-38 English industrial workers 8,905 39.5 45.4

1953-54 Cambridgeshire families 3,000 25.5 33.2

1971 United Kingdom families 7,239 26.0 30.0

1978 United Kingdom families 7,001 28.0 35.0

Source: 1695—"A First Draft of Gregory King's 'Observations' from his Notebook, 1695 and

Journal, 1696," in Seventeenth-Century Economic Documents, edited by Joan Thirsk and

J. P. Cooper (Oxford, 1972), pp. 767-68, and Gregory King, "A Scheme of the Income and

Expense of the Several Families of England Calculated for the Year 1688," Thirsk and

Cooper, pp. 780-81. 1787-93—David Davies, The Case of Labourers in Husbandry (Bath,

1795) and George Stigler, "The Early History of Empirical Studies of Consumer

Behavior," The Journal of Political Economy, 62 (1954), p. 97. 1794-96—Frederic Morton

Eden, The State of the Poor, vols. 2, 3 (London, 1797), and Stigler, "History Consumer

Behavior," 97. 1836, 1841—William Neild, "Comparative Statement of the Income and

Expenditures of Certain Families of the Working Classes in Manchester and Dukinfield, in

the years 1836 and 1841," Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 4 (1841), 320-35. 1837-

38—Frederick Purdy, "On the Earnings of Agricultural Labourers in England and Wales,

1860," Ibid., 24 (1861), 328-73. 1890-91—United States, Seventh Annual Report of the

Commissioner of Labor 1891 (Washington, D.C., 1892), pp. 2000-07. 1904—Augustus D.

Webb, The New Dictionary of Recent Statistics of the World to the Year 1911 (Leipzig,

1911), p. 157. 1929—D. Caradog Jones, The Social Survey of Merseyside, vol. 1

(Liverpool, 1934), p. 216, and R. G. D. Allen and A. L. Bowley, Family Expenditure

(London, 1935), p. 32. 1937-38—The Ministry of Labour Gazette, 48 (Dec. 1940), 300-05

and J. L. Nicholson, "Variations in Working Class Family Expenditure," Journal of the

Royal Statistical Society, ser. A (general), 112 pt. IV (1949), 394. 1953-54—Dorothy Cole

and J. E. G. Utting, "Estimating Expenditures, Savings, and Income from Household

Budgets, Ibid., 119 pt 4. (1956), 321-87. 1971—Great Britain, Central Statistical Office,

Social Trends, no. 3 (1972), p. 100. 1978—Ibid., no. 11 (1981), p. 113.

small scale by social reformers or public officials during the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The first major survey on

British family expenditure was undertaken in 1890 by the United States

Commissioner of Labor for comparative purposes.5

Although many of the percentages are high, nowhere does it appear

that 80 percent of expenditures went toward diet. From what is known

3

Lynn Hollen Lees, "Getting and Spending: The Family Budgets of English Industrial Workers

in 1890," in Consciousness and Class Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe, ed. John

Merriman (New York, 1979), pp. 169-86, discusses the 1890-1891 survey.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

92 Shammas

about rents, clothing costs, and the number of sundries required to live

in previous centuries, it would seem literally impossible for families

over prolonged periods to have spent four-fifths of earnings on diet. At

the same time no very clear trend surfaces until the twentieth century

when the proportion declines from 60 percent to about one quarter for

average households, and from two-thirds to one-third for the poor.

During the 1970s, the percentages begin to creep up again, suggesting

the beginning of a reversal.

There are problems, of course, with accepting all of these figures at

face value. One major difficulty is that in many of the surveys not all

types of miscellaneous expenditure were included, making the total

expenditure figure too small and hence the percentage accruing to food

inflated. This problem clearly affected the large United Kingdom

working class survey of 1904. Only a few expenses apart from clothing,

rent, and fuel were calculated so that only 4 percent of budget fell into

the miscellaneous category compared with 18!/2 percent in the 1890

survey.6 To a lesser extent, all the earlier surveys suffer from omissions

of this sort.

They also have another problem. In the years before offices were

established to compile statistics on a regular basis, individuals seldom

gathered figures except in times of crisis. In 1695, Gregory King wanted

to alert the government to the disastrous impact of the war with France

on the laboring population.7 Another war and skyrocketing food prices

at the end of the eighteenth century prompted the household budget

surveys taken by David Davies and Frederic Eden. Likewise the

economic crisis of the late 1830s and 1840s spurred local and House of

Commons investigations. The percentage of expenditures devoted to

food in these years was probably uncommonly high. Some indication of

how the percentages could seesaw within a few years' time is revealed

by the two entries for Manchester, England in 1836 and 1841. In the

latter year, the mayor, William Neild, had a survey taken of the

expenditures made by 19 working-class households in his city and

nearby Dukinfield to illustrate the effects of the depression on people in

the area. The investigators found diet absorbed 69 percent of the

workers' weekly outlays. They then figured what it would have cost in

1836 to buy the same goods and arrived at the much lower figure of 55

percent for that year. In other words, during one of these bad spells food

expenditure percentages could climb suddenly—in this case, 14 percent.

It seems possible, therefore, that the percentages in the high 60s and low

70s recorded for laborers during the late seventeenth and late eighteenth

centuries might have been in the mid-50s in better years.

6

D. Caradog Jones, The Social Survey of Merseyside, vol. 1 (Liverpool, 1934), p. 228.

7

G. S. Holmes, "Gregory King and the Social Structure of Pre-Industrial England," Transac-

tions of the Royal Historical Society, fifth series, 27 (1977), discusses the motivation behind King's

research. The method used to calculate the percentages from King's data are available from the

author.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-Being 93

The scarcity and shortcomings of English budget data for the period

before the late nineteenth century suggest the need to look elsewhere

for material on food expenditures in order to learn something about

trends within the early modern period. One possible source is wage

assessments, those schedules approved by Parliament and, after 1563,

set by the local justices of the peace. Assessments fixed the maximum

wage that could be paid to artisans, agricultural workers, and servants.

For those wages paid on a daily basis, usually two figures were

promulgated—one with diet furnished by the employer and one without

diet being provided. By subtracting the wage with diet from the wage

without diet and dividing the difference by the wage without diet, one

obtains the percentage of the wage that the authorities assumed would

go for food and drink. Assessments are far from ideal documents to use

for this purpose. Some counties, such as Middlesex, did not alter their

rates much for over a century. Enforcement was undoubtedly lax at

times and masters would pay more than the set amounts. Estimates

after the mid-eighteenth century are few and far between because the

practice of employers furnishing full diet to workers died out. Further-

more, the wages were daily rates for male individuals, not family

budgets. Were workers supposed to feed a wife and several children on

this pay? Probably not. Laborers' families would have additional

sources of income from so-called secondary workers and, frequently,

the parish poor rates. According to the figures furnished by David

TABLE 2

PERCENTAGE OF WAGE DEVOTED TO DIET

ENGLAND 1420-1780

Real

Wage

Date North West East AlP Index

Laborers

1420-1514 43.4% 897"

1560-1600 61.7% 51.2% 52.7% 55.0 559

1601-1640 63.3 53.0 50.0 54.9 411

1641-1680 56.7 53.1 47.6 51.9 473

1681-1720 58.3 54.0 47.9 52.9 553

1721-1760 52.7 53.0 48.2 51.0 658

Master Carpenters

1420-1514 — — 31.9% 897"

1560-1600 48.1% 43.9% 41.4% 44.1 559

1601-1640 45.7 48.3 47.0 47.0 411

1641-1680 50.0 50.2 43.5 47.5 473

1681-1780 45.8 45.8 43.4 44.8 615

" Percentage obtained by a weighted average of North (30 percent), West (30 percent), East (40

percent).

b

Average of 1499-1514 only.

Source: 1420-1514—Coventry 1420, 1444 statute, 1445 statute, 1495-96 statute, 1514 statute; Ellen

M. McArthur, "A Fifteenth-century Assessment of Wages," English Historical Review,

13 (1898), 299-302, Victoria County History, Warwickshire (London, 1908), 11, 180;

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

94 Shammas

Frederic Morton Eden, The State of the Poor (London, 1797), 1, pp. 65, 74-75, 81; 111,

lxxxix.

1560-1600—North: Lines. 1663, Rut. 1563, York 1563, Lincoln 1563, Hull, 1570,

Doncaster, 1577, Yorks. East Riding, 1593, Lancashire 1595; West: Exeter 1564-95,

Salisbury, 1595, Devonshire 1594-95; East: Northants. 1560, 1566, 1595, Bucks., 1561,

Kent, 1563, 1565, 1589, Berks. 1563, London 1563-1580, Canterbury, 1576, 1594,

Colchester, 1583, Herts. 1591; B. H. Putnam, "Northamptonshire Wage Assessments of

1560 and 1667," Economic History Review, 1 (1927-28), pp. 124-34. R. H. Tawney and E.

Power, eds., Tudor Economic Documents (London, 1935) 1, pp. 334-38, Paul L. Hughes

and James F. Larkin, eds., Tudor Royal Proclamations (New Haven, 1969), 3 vols.,

passim.

1601-1640—North: Rut. 1610, Lincolnshire, 1621; West: Wiltshire, 1603-34, 1635,

Merrioneth, 1601, Gloucester, 1632, Herefordshire, 1632; East: Middlesex 1608-40,

Norfolk, 1610, Suffolk 1630; Walter Davies, General View of the Agriculture and Domestic

Economy of North Wales (London, 1813), pp. 500-01, William Cunningham, The Growth

of English Industry and Commerce in Modern Times (Cambridge, 1929), pt. 11, pp. 887-

93, J. C. Tingey, "An Assessment of Wages for the County of Norfolk in 1610," English

Historical Review, 13 (1898), 522-27, Great Britain, Historical Manuscript Commission

(London, 1901), pp. 160-75, Ibid., Twelfth Report, Appendix part IV, Manuscripts of the

Duke of Rutland I (London, 1888), pp. 450-52, W. A. J. Archbold, "An Assessment of

Wages for 1630," English Historical Review, 12 (April 1897), 307-11, James E. Thorold

Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices in England (Oxford, 1887), VI, passim; W. E.

Minchinton, ed., Wage Regulation in Pre-Industrial England (Newton Abbot, 1972), p.

203

1641-80—North: Yorkshire West Riding 1647-1670, Yorkshire North Riding 1658,

Yorkshire East Riding 1669; West: Wiltshire 1654, 1655, Gloucestershire 1655, Somerset-

shire 1651-53, 1666, 1668-70, 1671-72, 1673, Worcestershire 1663, Herefordshire, 1666,

1667, 1668-80, Warwickshire, 1672; East—Essex 1651, 1661, Middlesex 1641-80, North-

ants. 1667; Cunningham, pp. 887-93, Hist. Ms., Various 1, pp. 160-75, Rogers, VI,

passim; Putnam, pp. 124-34, Roger Kelsall, "Two East Yorkshire Wage Assessments

1669, 1679," English Historical Review, 52 (1937), 283-89, Great Britain, Historical

Manuscript Commission, Fifteenth Report, Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections

1 (London, 1901), p. 323; Eleanor Trotter, Seventeenth Century Life in the Country Parish

(Cambridge, England, 1919), pp. 161-62; A. W. Ashby, One Hundred Years of Poor Law

Administration in a Warwickshire Village (Oxford, 1912), 170-83; H. Heaton, "The

Assessment of Wages in the West Riding of Yorkshire in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Centuries," Economic Journal, 24 (1914), 218-35; Minchinton, ed. pp. 160-61, 203.

1681-1720—North: Yorkshire West Riding; 1703-20 West: Wilts. 1685, Warwickshire,

1684, 1710, Somersetshire 1680-85, Herefordshire, 1680-82, 1684, 1702, 1703-06, 1710,

Somersetshire, 1680-85, Herefordshire, 1680-82, 1684, 1702, 1703-06, 1707 and 1711,

1708-10, 1712-20, Devonshire, 1700-20; East—Middlesex 1681-1720, Bedfordshire, 1684,

Suffolk, 1682; Rogers VI, VII, passim; VCH, Warwickshire, 11, p. 180; Cunningham, pp.

887-93; Elizabeth W. Gilboy, Wages in Eighteenth Century England (Cambridge, Massa-

chusetts, 1934), p. 88; Minchinton, ed., pp. 160-61, 203; T. S. Willan, "A Bedfordshire

Wage Assessment of 1684," Publications of the Bedfordshire Historical Record Society,

25 (1943), 129-37.

1721-1780—North: Yorkshire West Riding 1721-32, Nottingham 1723, Lancashire,

1725, Lincolnshire 1754; West: Devonshire 1721-32, 1733-78, Herefordshire, 1732, 1733-

62, Warwickshire 1730, Shropshire 1732-39; East: Middlesex 1721-25, Kent, 1724; Rogers

VII passim; J. D. Chambers, Nottinghamshire in the Eighteenth Century (New York,

1966, orig. published 1932), pp. 280-84, Eden, 111, cvi-cix; Victoria County History,

Lincolnshire 11 (London, 1906), pp. 345-46; Minchinton, ed., pp. 204; Gilboy, p. 88;

Ashby, pp. 171-83; F. A. Hibbert, "The Shropshire Wages Assessment at Easter 1732,"

Economic Journal, 4 (1894), pp. 516-17, Elizabeth Waterman, "Some New Evidence on

Wage Assessments in the Eighteenth Century," English Historical Review, 43 (July 1928),

pp. 398-408; Cunningham, pp. 887-93.

Real wage index is in E. A. Wrigley and R. S. Schofield, The Population History of

England 1741-1871 (London, 1981), pp. 642-43.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-Being 95

Davies and Frederick Eden in the 1780s and 1790s, the earnings of a

household head in the majority of cases constituted less than two-thirds

of a laboring-class household's total expenditure. The food allowance in

wage assessments, therefore, is an indication of what each male worker

buying meals for himself would allot to diet. It is not a family wage out

of which meals for wife and children should also be deducted to obtain

the proportion of household expenditure devoted to food.8

Despite these difficulties, the assessments do indicate what propor-

tion of a wage contemporaries believed went towards diet, and in terms

of trends over time and variations among regions, it matters little

whether it is a laborer's wage or a family's expenditures that is

represented. In Table 2, then, are the proportions ©f wages allowed for

food and drink by time period and region. Percentages for two types of

workers are shown: laborers (mainly agricultural but some urban) and

master carpenters, the former representing those at the bottom of the

working-class hierarchy and the latter representing those near the top.

Two principal points can be made about these series. First, both the

carpenters' and the laborers' percentages for the entire period are much

lower than the proportions found in the 1695 and late eighteenth century

budgets of Table 1. Leaving aside the pre-1560 data for a moment—the

table shows laborers allotted from 47.6 percent to 63.3 percent to diet

and carpenters 43.4 percent to 50.2 percent depending upon time and

region.9

The second point involves the pattern over time. The strikingly low

percentage of wages devoted to diet in the fifteenth and early sixteenth

centuries corresponds to what has previously been described as the

effects of population size on food prices. For purposes of comparison, I

have included averages of the real wage index for each group of years.

As mentioned above, this index, on the cost side, is almost entirely (80

percent) a reflection of variations in the prices of food and drink.

Considering trends in the real wage index, what is surprising is the

rather erratic behavior of the food percentages for laborers after 1600 in

the East and the West of England. In the former, food percentages

began declining in the early seventeenth century, but did not continue

the decline in the eighteenth despite higher real wages. In the West

percentages continue to rise through 1640, as might be assumed, but no

decline occurs thereafter. Only in the North among laborers does one

see the kind of dramatic increase in food percentages in the 1560-1640

8

The standard guide to wage assessments for England is W. E. Minchinton, ed., Wage

Regulation in Pre-Industrial England (Newton Abbot, 1972). Donald Woodward, "Wage Rates and

Living Standards in Pre-Industrial England," Past and Present, 91 (May 1981), 28-46, presents

evidence that builders' wages were not their entire income.

9

Master carpenters' food percentages are probably too high because they had other sources of

income. Woodward, "Wage Rates."

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

96 Shammas

period and the sharp and continual drop after the mid-seventeenth

century that might be expected given the real wage situation.10

According to consumption theory, food is inelastic in comparison to

other goods. People have to eat, so in hard times the "real" amount

spent on diet remains constant although the nominal amount and the

food expenditure proportion might go up because of higher prices, lower

wages, or both. In good times when higher wages prevail, the amount

spent will not increase proportionally because people can only eat so

much. Consequently the percentage of the total budget devoted to diet

will go down. Here, though, with the wage assessments, the percent-

ages do not fluctuate to the degree one might assume, implying that the

amounts expended did and that diet expenditures were somewhat more

elastic among the working-class population in the early modern period

than theory would lead us to believe.

When economists examine late nineteenth-century and twentieth-

century budget data, they usually find that as workers' incomes rise the

percentage expended on food declines. When the cross-sectional house-

hold expenditure material gathered by Eden and Davies for late

eighteenth-century laborer's families is analyzed, the relationship is

precisely the reverse. The higher the income the higher the diet

percentage, while all the other categories of expenditure—clothing,

rent, and fuel—go down as total resources climb.11 The income elastic-

ity for food is over unity.12 While the figure may be partially attributed

to the impoverished state of the workers in the Davies and Eden

Studies, many budget inquiries in the modern period also excluded more

affluent wage earners or divided low-income groups into several catego-

ries according to their earnings. No such pattern as found in the 1780s

and 1790s appears, however. Food proportions are highest among the

poorest and vice versa.

Engel's law and the theory that has been built up around it came into

being at a time of rapidly falling percentages of household expenditures

devoted to food. These "laws" may not apply in all time periods. As

Table 1 shows, the percentages in the 1970s have begun to rise again.

Some of the increase may be attributed to falling real wages but there

may be other reasons as well: more meals taken outside the home, for

example. Likewise more than just Engel's law is needed to illuminate

the early modern situation.

10

The close inverse correlation between the real wage index and the food percentages for the

North is especially interesting because the data on which the index is based are from the South.

11

The tables in Stigler, "History of Consumer Behavior," p. 97, show this clearly.

12

The Eden and Davies data yield 193 usable observations and produce an elasticity for food of

1.069 (double log form with the log of household size included in the regression). N. F. R. Crafts,

"Income Elasticities of Demand and the Release of Labour by Agriculture during the British

Industrial Revolution," Journal of European Economic History, 9 (Spring, 1980), p. 157,

separating Davies and Eden and using many fewer observations, obtained slightly different results

although he also stresses high elasticity. Unlike Crafts, I used expenditures rather than income so

that my figures would be comparable to those of other budget studies.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-Being 97

What particularly requires explanation is the sluggish rise and decline

in the percentage of budget devoted to food in the eastern and western

portions of England given the sharp fall and then rise in wages vis-a-vis

food prices in this period. Why does there seem to be so much elasticity

in food demand? It appears that people did cut back on "real" pounds

sterling spent on consumption in the sixteenth and early seventeenth

century everywhere, except for laborers in the North. It has been

argued that dietary standards declined in Europe during this time, with

meat, butter, and egg consumption falling to compensate for the

increased price of grains, although it has never been proven for

England, specifically.13 The elasticity implies that even laborers had

some flexibility, however dismal was the diet for which they had to

settle. The percentages for laborers in the North suggest no such

margin. In this region, starvation-caused mortality crises continued

through the 1620s, and one finds food expenditure percentages climbing

up to 63.3 percent in the early seventeenth century. Northern workers

had no place to cut their food budget and thus their expenditures show a

more inelastic pattern.

The carpenters' food percentages fall below those of laborers, as

would be assumed, yet the gap narrows over time. Also the percentages

in all regions follow the real wage index even less closely than do those

of the laborers' despite the fact that the real wage index is based upon

builders' pay. Both tendencies give aid and comfort to the supposition

that early modern food expenditures have some of the characteristics

usually associated with "luxury" spending.

How might changes in diet help account for the trend observed here?

In terms of composition, the diet of English women and men today was

set in the eighteenth century. Wheat bread and butter, sugar, tea,

coffee, chocolate, potatoes, rice, tobacco, spirits all became a normal

part of life in the early modern period. Exactly when these items came

into constant usage and how it affected food expenditures, however, is

still not well established.

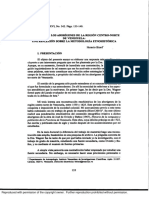

Figure 1 is a display of the food and drink that found its way into the

menus and account books of poorhouses and hospitals in both the

eastern and western portions of southern England from the Elizabethan

period to the end of the eighteenth century.14 Incorporation into an

institutional bill of fare usually indicates that a commodity is firmly

entrenched in the diet of the general population although the reverse is

13

Bartolome Bennassar and Joseph Goy, "Contribution a I'Histoire de la Consommation

Alimentaire du XIVe Siecle," Annales: Economies, Societies, Civilizations, 30 (Mars-Juin 1975), p.

427; and H. J. Teuteberg, "The General Relationship between Diet and Industrialization," in

European Diet from Pre-Industrial to Modern Times, edited by Elborg Forster and Robert Forster

(New York, 1975), p. 64.

14

On differences between the diet of southern England on the one hand and the Celtic fringe on

the other, see Brinley Thomas, "Feeding England During the Industrial Revolution: A View from

the Celtic Fringe," Agricultural History, 56 (January 1982), 328-42.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

98 Shammas

SE. ENGLAND S. ENGLAND S. ENGLAND S. ENGLAND

1570-1650 1687-1700 1725-1758 1773-1795

ANIMAL

PRODUCTS

GRAINS

VEGETABLES

Other: Turnips,

Cabbage, etc.

FRUITS Dried and Fresh

Beer

mm* wmm

DRINKS

Tea

Distilled Liquor

•IP

Hlta

Chocolate and

Coffee

Salt

OTHER Sugar

Spices

'aside from that used in Beer

| | SELDOM OR NEVER CITED

W$ffl SOMETIMES CITED

^ ^ | CONSTANTLY CITED

FIGURE 1

POORHOUSE DIETS IN SOUTHERN ENGLAND, 1570-1800

Source: 1570-1650—John Webb, ed. Poor Relief in Elizabethan Ipswich in Suffolk Record

Society, 9 (1906); "Orders Rules Directions . . . Justices of the Peace . . . Suffolk . . .

[1598] . . . Bury, Suffolk," in Frederic Morton Eden, The State of the Poor (London,

1797), pp. cxxvi-cxliii; Paul Slack, ed., Poverty in Early-Stuart Salisbury in Wiltshire

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Food Expenditures and Economic Well-Being 99

not necessarily true. Tea, spirits, and tobacco seldom appear because of

moral objections to these substances during the eighteenth century.

Nevertheless the poorhouse rules forbidding them and evidence from

non-institutional sources demonstrate widespread consumption.

According to Figure 1, the standard menu of bread, cheese, peas,

meat or fish, beer, and vegetables in season prevailed from the sixteenth

century to the middle of the seventeenth century. The bread was usually

a mixture of grains. At the end of the seventeenth century, some of the

new commodities—rice and potatoes—began appearing occasionally.

The unprecedented heavy use of sugar was by far the most important of

the developments in these years, however, because it made puddings of

wheat, oats, or rice much more palatable. Frumenty, panado, hasty

pudding, and rice milk showed up with even greater frequency in the

1725-1758 period. Potatoes apparently disappeared, but they reemerged

with a vengeance after the 1750s in practically every workhouse menu.

The consumption of tea in England began in the last half of the

seventeenth century and had become common in the southeast by the

1720s.15 Tea as a desirable drink was another byproduct of the sugar

revolution, and together the two changed the composition of breakfasts

and suppers. Brown bread, cheese, and beer gave way to the new drink,

its sweetener, and white wheat bread with butter.

Some indication of the importance that the new commodities had

assumed in the diet of laboring people by the end of the early modern

period is revealed in the household budgets collected in the 1780s and

1790s. "Groceries," those imported foodstuffs, selected provisions, and

15

A third of inventories from East London, a poor area, contained tea and/or coffee utensils by

the 1720s. Carole Shammas, "The Domestic Environment in Early Modern England and

America," Journal of Social History, 14 (Fall 1980), p. 12, Table II.

Record Society, 31 (1975), p. 11, 111-2, 118; [Samuel Hartlib], London's Charity Inlarged

(London, 1650).

1687-1700—"St. Bartholomew's Hospital . . . 1687," in J. C. Drummond and Anne

Wilbraham, The Englishman's Food (London, 1957, second edition), pp. 104-05; Anon. A

Modest Proposal . . . Provision for the Poor (London, 1696), p. 7; E. E. Butcher, ed.,

Bristol Corporation of the Poor 1696-1834, in Bristol Record Society Publications, 3

(1932), pp. 68-69; John Cary, An Account of the Proceedings of the Corporation of Bristol

(London, 1700), p. 12.

1725-1758—Anon, An Account of Several Workhouses for Employing and Maintaining

the Poor (London, 1725) and second edition (London, 1732); R. H. Lightning, Eating and

the Poor, Ealing Local History Society member paper no. 7, typescript 1966; Anon.

Statutes, Rules and Orders for . . . County Hospital for the Sick and Lame Poor,

Northampton (Northampton, 1743); Elizabeth Melling, Kentish Sources: IV The Poor

(Maidstone, 1964), pp. 96-97; [Jonas Hanway], A Plan for Establishing a Charity-House

. . . (London, 1758), pp. 24-26.

1773-1795—Anon. Norwich and Norfolk Hospital (London, 1773), pp. 37-38; C. E.

Mullineaux, Pauper and Poorhouse: Administration of Poor Laws in a Lancashire Parish

(Pendlebury, 1966), pp. 10-12; Arthur Young, comp. Annals of Agriculture (London,

1795), vol. 23; Eden, State of Poor, vols. II, III, passim, poorhouse menus and accounts in

the South of England.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

100 Shammas

haberdashery items sold in generalized shops, appear in nearly every

family listing. Tea, sugar, and potatoes alone constituted 12.4 percent of

food and drink expenditures, almost the same proportion as meat

purchases. The same could be said for outlays on other new commod-

ities. The competition between butter and cheese and the struggle for an

ever whiter wheat bread also gave the consumer new places to put his or

her cash. Undoubtedly some of the changes were made to save money

and certainly very few of them necessarily led to better nutrition. They

do suggest, however, some reasons for the perceived elasticity of food

expenditures in the later part of the early modern period.

II

Consumer behavior in dietary matters during the early modern period

appears to differ from that in late nineteenth- and twentieth-century

England. No dramatic fall in the proportion of household outlays

devoted to food occurred. In fact, it is likely that the percentage rose

sharply in the sixteenth century and late seventeenth and eighteenth

century declines were insufficient to bring back fifteenth century levels.

The proportions, however, fell into the 50-60 percent range for the

laboring classes rather than the 80 percent often used in cost of living

indices.

It also may be inappropriate for the early modern period to classify

spending for clothing and consumer durables as elastic and food buying

as inelastic. Outlays had to be made for rent, fuel, soap, candles, and

apparel. Flexibility was often limited. On the other hand, consumers

could change the grain and the grade of their bread, increase or decrease

their intake of meat and sugar, substitute cheese for butter or caffeine

drinks and spirits for beer. The failure of the percentage of expenditure

devoted to diet to decline further in the late seventeenth or the

eighteenth century may be due to the variety of commodities to put in

one's mouth. It may also explain why the consumer durables that

enjoyed the biggest boom in this period were eating and drinking

utensils.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029041 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Agriculture and Rural Society after the Black Death: Common Themes and Regional VariationsFrom EverandAgriculture and Rural Society after the Black Death: Common Themes and Regional VariationsNo ratings yet

- Population Geography: Pergamon Oxford GeographiesFrom EverandPopulation Geography: Pergamon Oxford GeographiesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Agricultural Revolution in EnglandDocument21 pagesAgricultural Revolution in EnglandApurbo MaityNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Agrarian Capitalism and The Decline of Family Farming in ...Document39 pagesThe Rise of Agrarian Capitalism and The Decline of Family Farming in ...Henrique GomesNo ratings yet

- Allen Revoluciones AgrícolasDocument28 pagesAllen Revoluciones AgrícolasAna martinezNo ratings yet

- The British Industrial Revolution in Global PerspectiveDocument4 pagesThe British Industrial Revolution in Global PerspectiveUsamaNo ratings yet

- Vegetarians or Carnivores Standards of L PDFDocument33 pagesVegetarians or Carnivores Standards of L PDFMátyás SüketNo ratings yet

- Deane and ColeDocument11 pagesDeane and ColeFernando SchneiderNo ratings yet

- Consumer Prices and Wages in Germany, 1500 - 1850: WWU MünsterDocument46 pagesConsumer Prices and Wages in Germany, 1500 - 1850: WWU MünsterKennyNo ratings yet

- Slavin PDFDocument14 pagesSlavin PDFShiviNo ratings yet

- Blackwell Publishing Economic History SocietyDocument28 pagesBlackwell Publishing Economic History SocietyalxNo ratings yet

- Campbell - 2012 Let Us Eat CakeDocument17 pagesCampbell - 2012 Let Us Eat CakeevaNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Global Availability of Food: Continued Abundance or New Scarcity?Document64 pagesLong-Term Global Availability of Food: Continued Abundance or New Scarcity?Mateo Armando MeloNo ratings yet

- Economic GrowthDocument51 pagesEconomic GrowthOzlem100% (1)

- (Studies in Economic and Social History) R. J. Overy (Auth.) - The Nazi Economic Recovery 1932-1938 (1982, Macmillan Education UK)Document76 pages(Studies in Economic and Social History) R. J. Overy (Auth.) - The Nazi Economic Recovery 1932-1938 (1982, Macmillan Education UK)salman khanNo ratings yet

- Swift EssayDocument10 pagesSwift EssayJasmine KolanoNo ratings yet

- British Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Document48 pagesBritish Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Sabrina CanţîrNo ratings yet

- Robert AllenDocument28 pagesRobert AllenMadhupriya SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 Living StandardsDocument30 pagesLecture 2 Living Standardsანთეა აბრამიშვილიNo ratings yet

- Term Paper 1 EP-405: Written By: Priyanka ChowdharyDocument13 pagesTerm Paper 1 EP-405: Written By: Priyanka ChowdharyPriyanka ChowdharyNo ratings yet

- Welfare Impact of Food PriceDocument37 pagesWelfare Impact of Food PriceIoproprioioNo ratings yet

- Guido Alfani - Cormac O Grada - Famine in European History-Cambridge University Press (2017)Document340 pagesGuido Alfani - Cormac O Grada - Famine in European History-Cambridge University Press (2017)JimmyNo ratings yet

- The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First CenturyFrom EverandThe Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- 0521847567Document453 pages0521847567Sybella Antonucci Antonucci100% (1)

- John RuleDocument143 pagesJohn Ruleivanpiermatei71No ratings yet

- F.M.L. Thompson - The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750-1950, Vol. 02. People and Their EnvironmentDocument380 pagesF.M.L. Thompson - The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750-1950, Vol. 02. People and Their EnvironmentStevens DornNo ratings yet

- Everyday Life in Medieval EnglandDocument353 pagesEveryday Life in Medieval Englandbrianb@mbarchitects.us100% (27)

- Humphries 2013Document22 pagesHumphries 2013Historia UdeChile DosmilOchoNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Economic and Social History) Donald N. McCloskey (Auth.) - Econometric History-Macmillan Education UK (1987) PDFDocument115 pages(Studies in Economic and Social History) Donald N. McCloskey (Auth.) - Econometric History-Macmillan Education UK (1987) PDFLuis Angel Velastegui-MartinezNo ratings yet

- Household Strategies For SurvivalDocument17 pagesHousehold Strategies For SurvivalVíctor Ferreras PresaNo ratings yet

- Population GrowthDocument13 pagesPopulation GrowthManel MamitooNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 39Document42 pages10 1 1 39bensbloom159No ratings yet

- The Historical Fertility Transition: A Guide For Economists: Timothy W. GuinnaneDocument27 pagesThe Historical Fertility Transition: A Guide For Economists: Timothy W. GuinnaneValentina PortoNo ratings yet

- ContentserverDocument25 pagesContentserverapi-317753006No ratings yet

- English Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionDocument26 pagesEnglish Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionPradyumna BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Munro5@chass - Utoronto.ca John - Munro@utoronto - CaDocument73 pagesMunro5@chass - Utoronto.ca John - Munro@utoronto - CaAhmad SyahirNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.030Document23 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.030Camila CrumoNo ratings yet

- A Long History of Blaming Peasantsthe Journal of Peasant StudiesDocument21 pagesA Long History of Blaming Peasantsthe Journal of Peasant Studies周思中No ratings yet

- The Myth of The Agricultural RevolutionDocument9 pagesThe Myth of The Agricultural RevolutiontrashcanxtxNo ratings yet

- Malthusian TrapDocument3 pagesMalthusian TrapfataoulNo ratings yet

- English Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionDocument26 pagesEnglish Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionKrissy937No ratings yet

- The Emergence of Britain As The WorldDocument7 pagesThe Emergence of Britain As The Worldumar13aliNo ratings yet

- Allen Impact On PeopleDocument12 pagesAllen Impact On PeopleobamaNo ratings yet

- A Short History of English Agriculture by Curtler, W. H. R.Document270 pagesA Short History of English Agriculture by Curtler, W. H. R.Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- 16 - 92 - Past and Present Definitions of The Energy and Protein Requirements For RuminantsDocument16 pages16 - 92 - Past and Present Definitions of The Energy and Protein Requirements For Ruminantsabdelaziz CHELIGHOUMNo ratings yet

- Agriculture PDFDocument54 pagesAgriculture PDFMeer FaisalNo ratings yet

- Paradigm ShiftDocument7 pagesParadigm Shiftapi-356397636No ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument27 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldAnonymous GPiFpUpZ9gNo ratings yet

- BBC - History - British History in Depth - Agricultural Revolution in England 1500 - 1850Document4 pagesBBC - History - British History in Depth - Agricultural Revolution in England 1500 - 1850Ayush SinghalNo ratings yet

- Environmental Science NotesDocument109 pagesEnvironmental Science NotesHira ZafarNo ratings yet

- Terence Kealey - The Economic Laws of Scientific Research-Palgrave Macmillan (1997)Document398 pagesTerence Kealey - The Economic Laws of Scientific Research-Palgrave Macmillan (1997)Diego Barbosa dos ReisNo ratings yet

- European PopulationsDocument5 pagesEuropean PopulationswinstonandchiaoNo ratings yet

- Making A Living in The Middle Ages The People of Britain, 850-1520Document437 pagesMaking A Living in The Middle Ages The People of Britain, 850-1520Юра Шейх-ЗадеNo ratings yet

- Ehi 7 emDocument10 pagesEhi 7 emFirdosh KhanNo ratings yet

- Bickham - Eating The EmpireDocument40 pagesBickham - Eating The EmpireMarуana MyroshNo ratings yet

- Cambridge British Industrial RevolutionDocument38 pagesCambridge British Industrial RevolutionRachael VazquezNo ratings yet

- Agricrultural Révolution in England 1500-1850: An EnduringDocument3 pagesAgricrultural Révolution in England 1500-1850: An Enduringhaythemtroudi90No ratings yet

- Written AssignmentDocument6 pagesWritten AssignmentChau KerstinNo ratings yet

- Economic SystemsDocument33 pagesEconomic SystemsThu PhạmNo ratings yet

- Fjellstrom - Food Cultures in SapmiDocument120 pagesFjellstrom - Food Cultures in SapmiEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Horacio Biord Castillo - Estudio de Los Aborigenes Centro-Norte de VenezuelaDocument1 pageHoracio Biord Castillo - Estudio de Los Aborigenes Centro-Norte de VenezuelaEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Slatta, 1982 - Pulperías and Contraband Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Buenos Aires ProvinceDocument17 pagesSlatta, 1982 - Pulperías and Contraband Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Buenos Aires ProvinceEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Sima 2017 (Communist Heritage)Document18 pagesSima 2017 (Communist Heritage)EloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Marcuse Segregationandthe PDFDocument15 pagesMarcuse Segregationandthe PDFgiljermoNo ratings yet

- How To Make Caramel SauceDocument2 pagesHow To Make Caramel SauceEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Françoid Prendas y Pulperias PDFDocument40 pagesFrançoid Prendas y Pulperias PDFEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Curcuma - Physiological Barriers To The Oral Delivery of CurcuminDocument7 pagesCurcuma - Physiological Barriers To The Oral Delivery of CurcuminEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Web Resources For Metagenome StudiesDocument8 pagesWeb Resources For Metagenome StudiesEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- WRAHNGHAM, R. Cooking As A Biological TraitDocument12 pagesWRAHNGHAM, R. Cooking As A Biological TraitEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- AMBROSE, H. 2001. Paleolithic Technology and Human Evolution PDFDocument6 pagesAMBROSE, H. 2001. Paleolithic Technology and Human Evolution PDFEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- DIAMOND, J. The Worst Mistake in The History of HumanityDocument12 pagesDIAMOND, J. The Worst Mistake in The History of HumanityEloisaOTNo ratings yet

- Application & Registration Form MSC International Business Management M2Document11 pagesApplication & Registration Form MSC International Business Management M2Way To Euro Mission Education ConsultancyNo ratings yet

- Analog Circuits - IDocument127 pagesAnalog Circuits - IdeepakpeethambaranNo ratings yet

- Valuation of Bonds and Stocks: Financial Management Prof. Deepa IyerDocument49 pagesValuation of Bonds and Stocks: Financial Management Prof. Deepa IyerAahaanaNo ratings yet

- SWVA Second Harvest Food Bank Spring Newsletter 09Document12 pagesSWVA Second Harvest Food Bank Spring Newsletter 09egeistNo ratings yet

- Instructions For Form 8824Document4 pagesInstructions For Form 8824Abdullah TheNo ratings yet

- Inhuman Exclusive PreviewDocument12 pagesInhuman Exclusive PreviewUSA TODAY Comics100% (1)

- Handling and Working With Analytical StandardsDocument6 pagesHandling and Working With Analytical StandardsPreuz100% (1)

- Norma MAT2004Document12 pagesNorma MAT2004Marcelo Carvalho100% (1)

- Caso Contra Ángel Pérez: Respuesta de La Fiscalía A Moción de La Defensa Sobre Uso de FotosDocument8 pagesCaso Contra Ángel Pérez: Respuesta de La Fiscalía A Moción de La Defensa Sobre Uso de FotosEl Nuevo DíaNo ratings yet

- Rtcclient Tool Quick Guide: Date Jan. 25, 2011Document3 pagesRtcclient Tool Quick Guide: Date Jan. 25, 2011curzNo ratings yet

- CPS Fitting Stations by County - 22 - 0817Document33 pagesCPS Fitting Stations by County - 22 - 0817Melissa R.No ratings yet

- CASE Assignment #4Document3 pagesCASE Assignment #4Matti Hannah V.No ratings yet

- 6063 Grade Aluminum ProfileDocument3 pages6063 Grade Aluminum ProfileVJ QatarNo ratings yet

- Sim5360 Atc en v0.19Document612 pagesSim5360 Atc en v0.19Thanks MarisaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To The Automation Body of Knowledge, 2nd EditionDocument8 pagesA Guide To The Automation Body of Knowledge, 2nd EditionTito Livio0% (9)

- Pravin Raut Sanjay Raut V EDDocument122 pagesPravin Raut Sanjay Raut V EDSandeep DashNo ratings yet

- Jacob Engine Brake Aplicación PDFDocument18 pagesJacob Engine Brake Aplicación PDFHamilton MirandaNo ratings yet

- Growth of Luxury Market & Products in IndiaDocument60 pagesGrowth of Luxury Market & Products in IndiaMohammed Yunus100% (2)

- Barangay San Pascual - Judicial Affidavit of PB Armando DeteraDocument9 pagesBarangay San Pascual - Judicial Affidavit of PB Armando DeteraRosemarie JanoNo ratings yet

- Vashi Creek Water Quality NaviMumbaiDocument27 pagesVashi Creek Water Quality NaviMumbairanucNo ratings yet

- Dialux BRP391 40W DM CT Cabinet SystemDocument20 pagesDialux BRP391 40W DM CT Cabinet SystemRahmat mulyanaNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Law & Practice Code: BBA-301 Unit - 2: Ms. Manisha Sharma Asst. ProfessorDocument32 pagesIncome Tax Law & Practice Code: BBA-301 Unit - 2: Ms. Manisha Sharma Asst. ProfessorVasu NarangNo ratings yet

- DWC Ordering InformationDocument15 pagesDWC Ordering InformationbalaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Civil Liberties Union Vs Executive SecretaryDocument3 pages2 - Civil Liberties Union Vs Executive SecretaryTew BaquialNo ratings yet

- NAVA - Credit TransactionsDocument79 pagesNAVA - Credit Transactionscarrie navaNo ratings yet

- Legend Sheet P&ID For As-Built - Drafting On 20210722-5Document1 pageLegend Sheet P&ID For As-Built - Drafting On 20210722-5Ludi D. LunarNo ratings yet

- Skott Marsi Art Basel Sponsorship DeckDocument11 pagesSkott Marsi Art Basel Sponsorship DeckANTHONY JACQUETTENo ratings yet

- Ips M PM 330Document25 pagesIps M PM 330Deborah MalanumNo ratings yet

- Bafb1023 Microeconomics (Open Book Test)Document4 pagesBafb1023 Microeconomics (Open Book Test)Hareen JuniorNo ratings yet