Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heaven: This Article Is About The Divine Abode in Various Religious Traditions. For Other Uses, See

Uploaded by

Dileep kumar0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views4 pagesHeaven is described in many religious traditions as a divine abode where deities, angels, souls or ancestors reside. It is often conceived as the highest place, holiest place or paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld. In Abrahamic faiths like Christianity, Islam and some forms of Judaism, heaven is an afterlife realm where the righteous are eternally rewarded, while hell is a place of eternal punishment for the wicked. The concept of heaven has roots in ancient Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Phoenician and Zoroastrian religions, among others, and is believed by some to have influenced later traditions like Greek philosophy and Buddhism.

Original Description:

Heaven details

Original Title

3

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHeaven is described in many religious traditions as a divine abode where deities, angels, souls or ancestors reside. It is often conceived as the highest place, holiest place or paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld. In Abrahamic faiths like Christianity, Islam and some forms of Judaism, heaven is an afterlife realm where the righteous are eternally rewarded, while hell is a place of eternal punishment for the wicked. The concept of heaven has roots in ancient Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Phoenician and Zoroastrian religions, among others, and is believed by some to have influenced later traditions like Greek philosophy and Buddhism.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views4 pagesHeaven: This Article Is About The Divine Abode in Various Religious Traditions. For Other Uses, See

Uploaded by

Dileep kumarHeaven is described in many religious traditions as a divine abode where deities, angels, souls or ancestors reside. It is often conceived as the highest place, holiest place or paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld. In Abrahamic faiths like Christianity, Islam and some forms of Judaism, heaven is an afterlife realm where the righteous are eternally rewarded, while hell is a place of eternal punishment for the wicked. The concept of heaven has roots in ancient Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Phoenician and Zoroastrian religions, among others, and is believed by some to have influenced later traditions like Greek philosophy and Buddhism.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Heaven

82 languages

Article

Talk

Read

Edit

View history

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the divine abode in various religious traditions. For other uses,

see Heaven (disambiguation).

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may

interest only a particular audience. Please help by spinning

off or relocating any relevant information, and removing excessive detail that

may be against Wikipedia's inclusion policy. (February 2023) (Learn how and

when to remove this template message)

Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest heavens; from Gustave Doré's illustrations to the Divine

Comedy.

Heaven, or the heavens, is a common religious

cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such

as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate,

be enthroned, or reside. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings

can descend to Earth or incarnate and earthly beings can ascend to Heaven in

the afterlife or, in exceptional cases, enter Heaven alive.

Heaven is often described as a "highest place", the holiest place, a Paradise, in

contrast to hell or the Underworld or the "low places" and universally or conditionally

accessible by earthly beings according to various standards

of divinity, goodness, piety, faith, or other virtues or right beliefs or simply divine will.

Some believe in the possibility of a heaven on Earth in a world to come.

Another belief is in an axis mundi or world tree which connects the heavens, the

terrestrial world, and the underworld. In Indian religions, heaven is considered

as Svarga loka,[1] and the soul is again subjected to rebirth in different living forms

according to its karma. This cycle can be broken after a soul

achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Any place of existence, either of humans, souls or

deities, outside the tangible world (Heaven, Hell, or other) is referred to as

the otherworld.

At least in the Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Islam, and some schools of Judaism,

as well as Zoroastrianism, heaven is the realm of Afterlife where good actions in the

previous life are rewarded for eternity (hell being the place where bad behavior is

punished).

Etymology[edit]

"heofones", an ancient Anglo-Saxon word for heavens in Beowulf

The modern English word heaven is derived from the earlier (Middle

English) heven (attested 1159); this in turn was developed from the previous Old

English form heofon. By about 1000, heofon was being used in reference to

the Christianized "place where God dwells", but originally, it had signified "sky,

firmament"[2] (e.g. in Beowulf, c. 725). The English term has cognates in the

other Germanic languages: Old Saxon heƀan "sky, heaven" (hence also Middle Low

German heven "sky"), Old Icelandic himinn, Gothic himins; and those with a variant

final -l: Old Frisian himel, himul "sky, heaven", Old Saxon and Old High

German himil, Old Saxon and Middle Low German hemmel, Old

Dutch and Dutch hemel, and modern German Himmel. All of these have been

derived from a reconstructed Proto-Germanic form *hemina-.[3] or *hemō.[4]

The further derivation of this form is uncertain. A connection to Proto-Indo-

European *ḱem- "cover, shroud", via a reconstructed *k̑emen- or *k̑ōmen- "stone,

heaven", has been proposed.[5] Others endorse the derivation from a Proto-Indo-

European root *h₂éḱmō "stone" and, possibly, "heavenly vault" at the origin of this

word, which then would have as cognates ancient Greek ἄκμων (ákmōn "anvil,

pestle; meteorite"), Persian ( آسمانâsemân, âsmân "stone, sling-stone; sky, heaven")

and Sanskrit अश्मन ् (aśman "stone, rock, sling-stone; thunderbolt; the firmament").

[4]

In the latter case English hammer would be another cognate to the word.

Ancient Near East[edit]

See also: Category:Conceptions of heaven and Religions of the ancient Near East

Mesopotamia[edit]

Ruins of the Ekur temple in Nippur, believed by the ancient Mesopotamians to be the "Dur-an-ki", the

"mooring-rope" of heaven and earth [6][7]

Main article: Ancient Mesopotamian religion

The ancient Mesopotamians regarded the sky as a series of domes (usually three,

but sometimes seven) covering the flat Earth.[8] Each dome was made of a different

kind of precious stone.[9] The lowest dome of heaven was made of jasper and was

the home of the stars.[10][11] The middle dome of heaven was made of saggilmut stone

and was the abode of the Igigi.[10][11] The highest and outermost dome of heaven was

made of luludānītu stone and was personified as An, the god of the sky.[12][10]

[11]

The celestial bodies were equated with specific deities as well.[9] The

planet Venus was believed to be Inanna, the goddess of love, sex, and war.[13]

[9]

The Sun was her brother Utu, the god of justice, and the Moon was their

father Nanna.[9]

In ancient Near Eastern cultures in general and in Mesopotamia in particular,

humans had little to no access to the divine realm. [14][15] Heaven and Earth were

separated by their very nature;[11] humans could see and be affected by elements of

the lower heaven, such as stars and storms,[11] but ordinary mortals could not go to

Heaven because it was the abode of the gods alone. [15][16][11] In the Epic of

Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh says to Enkidu, "Who can go up to heaven, my friend? Only

the gods dwell with Shamash forever."[16] Instead, after a person died, his or her soul

went to Kur (later known as Irkalla), a dark shadowy underworld, located deep below

the surface of the earth.[15][17]

All souls went to the same afterlife,[15][17] and a person's actions during life had no

impact on how he would be treated in the world to come. [15][17] Nonetheless, funerary

evidence indicates that some people believed that Inanna had the power to bestow

special favors upon her devotees in the afterlife. [17][18] Despite the separation between

heaven and earth, humans sought access to the gods through oracles and omens.

[6]

The gods were believed to live in Heaven, [6][19] but also in their temples, which were

seen as the channels of communication between Earth and Heaven, which allowed

mortal access to the gods.[6][20] The Ekur temple in Nippur was known as the "Dur-an-

ki", the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth. [21] It was widely thought to have been

built and established by Enlil himself.[7]

Zoroastrians[edit]

Further information: Zoroastrian mythology

Zoroaster, the Zoroastrian prophet who introduced the Gathas, spoke of the

existence of Heaven and Hell.[22][23]

Historically, the unique features of Zoroastrianism, such as its conception of heaven,

hell, angels, monotheism, belief in free will, and the day of judgement, among other

concepts, may have influenced other religious and philosophical systems, including

the Abrahamic religions, Gnosticism, Northern Buddhism, and Greek philosophy. [24][25]

Canaanites and Phoenicians[edit]

Main article: Canaanite religion

Almost nothing is known of Bronze Age (pre-1200 BC) Canaanite views of heaven,

and the archaeological findings at Ugarit (destroyed c. 1200 BC) have not provided

information. The first century Greek author Philo of Byblos may preserve elements

of Iron Age Phoenician religion in his Sanchuniathon.[26]

You might also like

- Contract of LeaseDocument4 pagesContract of LeaseIelBarnachea100% (5)

- East Coast Yacht's Expansion Plans-06!02!2008 v2Document3 pagesEast Coast Yacht's Expansion Plans-06!02!2008 v2percyNo ratings yet

- Magic in Ancient Egypt - "I Am The Resurrection"Document13 pagesMagic in Ancient Egypt - "I Am The Resurrection"Karima Lachtane84% (19)

- Serpent CultsDocument8 pagesSerpent CultsAnthony Forwood100% (4)

- Hades: 2 God of The UnderworldDocument9 pagesHades: 2 God of The UnderworldValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Grade-9 (1st)Document42 pagesGrade-9 (1st)Jen Ina Lora-Velasco GacutanNo ratings yet

- Fritz Springmeier InterviewDocument59 pagesFritz Springmeier InterviewCzink Tiberiu100% (4)

- Lguvisitation-Municipality of CaintaDocument23 pagesLguvisitation-Municipality of CaintaDaniel BulanNo ratings yet

- Chthonic - WikipediaDocument1 pageChthonic - WikipediasuryokingposNo ratings yet

- World Egg: Jacob Bryant's Orphic Egg (1774)Document7 pagesWorld Egg: Jacob Bryant's Orphic Egg (1774)xRxTNo ratings yet

- Astral Projection OTTIMA DISANIMADocument6 pagesAstral Projection OTTIMA DISANIMAFiorenzo TassottiNo ratings yet

- ChaosDocument8 pagesChaosD HernandezNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian Conception of The SoulDocument9 pagesAncient Egyptian Conception of The Soulg711kNo ratings yet

- Adf CosmologyDocument5 pagesAdf Cosmologysamanera2No ratings yet

- Ananke: νάγκη ἀ fateDocument8 pagesAnanke: νάγκη ἀ fatevineeth kumarNo ratings yet

- 1Document5 pages1Ginaly PicoNo ratings yet

- Unaging TimeDocument38 pagesUnaging TimeJames HansNo ratings yet

- البا كعنصر فني ديني من مصر القديمه حتي عصر النهضهDocument31 pagesالبا كعنصر فني ديني من مصر القديمه حتي عصر النهضهMamdoh MohamedNo ratings yet

- Cosmic EggDocument4 pagesCosmic EggSlick Shaney100% (1)

- DuatDocument3 pagesDuatNabil RoufailNo ratings yet

- What Was The RaqiaDocument16 pagesWhat Was The RaqiaTim WrightNo ratings yet

- Concepts From The Bahir The Tree of Life in The KabbalahDocument3 pagesConcepts From The Bahir The Tree of Life in The Kabbalahek0n0m1k100% (1)

- After The AscentDocument14 pagesAfter The Ascenthieratic_headNo ratings yet

- This Article Is About The Abode of The Dead in Various Cultures and Religious Traditions Around The World. For Other Uses, SeeDocument4 pagesThis Article Is About The Abode of The Dead in Various Cultures and Religious Traditions Around The World. For Other Uses, SeeDileep kumarNo ratings yet

- Fossil Gods FinalDocument263 pagesFossil Gods FinalWK WK100% (2)

- Eye of HorusDocument19 pagesEye of Horusztanga7@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- AfterlifeDocument7 pagesAfterlifeBalaji SNo ratings yet

- Sky Father: in Historical MythologyDocument3 pagesSky Father: in Historical MythologyShadeNo ratings yet

- Indra: A Case Study in Comparative Mythology: Ev CochraneDocument28 pagesIndra: A Case Study in Comparative Mythology: Ev Cochranethade86No ratings yet

- Ancient Mesopotamian Underworld: Kigal and in Akkadian As ErDocument8 pagesAncient Mesopotamian Underworld: Kigal and in Akkadian As ErErdinc100% (1)

- Cosmology: Myth or Science?: Hannes AlfvénDocument20 pagesCosmology: Myth or Science?: Hannes AlfvénChirag SolankiNo ratings yet

- Ancient Stories: The Mythology Behind the Sky: Ancient Stories, #1From EverandAncient Stories: The Mythology Behind the Sky: Ancient Stories, #1No ratings yet

- Astral ProjectionDocument8 pagesAstral ProjectionNill Salunke100% (1)

- Bowden Nameless GodsDocument19 pagesBowden Nameless GodsHugh BowdenNo ratings yet

- Rochberg Mesopotamian Cosmology (2005)Document7 pagesRochberg Mesopotamian Cosmology (2005)葛学斌No ratings yet

- ZeusDocument39 pagesZeusstn28092No ratings yet

- 1.1. The Beginning How The World Were CreatedDocument52 pages1.1. The Beginning How The World Were Createdfroilan.tinduganNo ratings yet

- World Egg: Jacob Bryant's Orphic Egg (1774)Document7 pagesWorld Egg: Jacob Bryant's Orphic Egg (1774)Alison_VicarNo ratings yet

- Lucian's "True History". Its Credible Parts InterpretedFrom EverandLucian's "True History". Its Credible Parts InterpretedRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- Hollow EarthDocument8 pagesHollow EarthIrish TagayloNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology - 1Document472 pagesGreek Mythology - 1Gabriel Rok100% (8)

- Demigods BSHJDocument5 pagesDemigods BSHJInvisible CionNo ratings yet

- Oracle InformationDocument7 pagesOracle InformationAnonymous 2HXuAeNo ratings yet

- Tabula Smaragdina HermetisDocument7 pagesTabula Smaragdina HermetisMyndianNo ratings yet

- Belief and MeaningsDocument3 pagesBelief and MeaningsiamkuttyNo ratings yet

- The Gnostic Creed, Seeds of Self KnowledgeDocument11 pagesThe Gnostic Creed, Seeds of Self KnowledgeChristsballs100% (1)

- 2652-Article Text-11126-1-10-20230510Document15 pages2652-Article Text-11126-1-10-20230510Hassan Jacob AguimesheoNo ratings yet

- Forgotten History - Mike GascoigneDocument5 pagesForgotten History - Mike GascoigneSammy DavisNo ratings yet

- Cern LHCDocument5 pagesCern LHCWilliam Scott100% (1)

- Stellar Lightning - The Inventory StelaDocument10 pagesStellar Lightning - The Inventory StelaDAVIDNSBENNETTNo ratings yet

- Religious CosmologyDocument7 pagesReligious Cosmologysebastian431No ratings yet

- Aphrodite and Theology Pp. 94-110 in BL PDFDocument17 pagesAphrodite and Theology Pp. 94-110 in BL PDFcodytlseNo ratings yet

- Anunnaki Nephilim: (Willy Schrodter, Commentaries On The Occult Philosophy of Agrippa)Document4 pagesAnunnaki Nephilim: (Willy Schrodter, Commentaries On The Occult Philosophy of Agrippa)nikoNo ratings yet

- Afterlife - WikipediaDocument7 pagesAfterlife - WikipediaNyx Bella DarkNo ratings yet

- Civilization Egyptian: Men and Occult PowersDocument6 pagesCivilization Egyptian: Men and Occult Powerscalmafermezza100% (1)

- Claudio Mutti - The Doctrine of Divine Unity in Hellenic TraditionDocument7 pagesClaudio Mutti - The Doctrine of Divine Unity in Hellenic TraditionashfaqamarNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - MythoDocument18 pagesLesson 2 - MythoBrixylle AnneNo ratings yet

- The Divinity of The Pharaoh in Greek SourcesDocument5 pagesThe Divinity of The Pharaoh in Greek Sources田富No ratings yet

- Hades: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument21 pagesHades: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchmagusradislavNo ratings yet

- The Decadence of The Shamans or Shamanism As A Key To The Secrets of CommunismDocument43 pagesThe Decadence of The Shamans or Shamanism As A Key To The Secrets of CommunismPeter SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Cornutus On Greek TheologyDocument24 pagesCornutus On Greek TheologyPainThuzadNo ratings yet

- Zin 2014 Hell PDFDocument28 pagesZin 2014 Hell PDFPrakriti AnandNo ratings yet

- Devil: For Other Uses, SeeDocument4 pagesDevil: For Other Uses, SeeDileep kumarNo ratings yet

- 4Document4 pages4Dileep kumarNo ratings yet

- This Article Is About The Abode of The Dead in Various Cultures and Religious Traditions Around The World. For Other Uses, SeeDocument4 pagesThis Article Is About The Abode of The Dead in Various Cultures and Religious Traditions Around The World. For Other Uses, SeeDileep kumarNo ratings yet

- Drilling RigDocument4 pagesDrilling RigDileep kumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 and 2Document75 pagesChapter 1 and 2Balamurali SureshNo ratings yet

- Advertising & SALES PROMOTIONAL-AirtelDocument78 pagesAdvertising & SALES PROMOTIONAL-AirtelDasari AnilkumarNo ratings yet

- pr40 03-EngDocument275 pagespr40 03-EngLUZ CERONNo ratings yet

- Human Rights RapDocument4 pagesHuman Rights Rapapi-264123803No ratings yet

- The Wise Old WomenDocument2 pagesThe Wise Old WomenLycoris FernandoNo ratings yet

- Forest Field Trip ReportDocument8 pagesForest Field Trip Reportapi-296213542100% (2)

- ASA 105: Coastal Cruising Curriculum: Prerequisites: NoneDocument3 pagesASA 105: Coastal Cruising Curriculum: Prerequisites: NoneWengerNo ratings yet

- Bearing CapacityDocument4 pagesBearing CapacityahmedNo ratings yet

- List of All ProjectsDocument152 pagesList of All ProjectsMhm ReddyNo ratings yet

- SnapManual PDFDocument77 pagesSnapManual PDFnaser150No ratings yet

- Part 1-2 ProblemsDocument4 pagesPart 1-2 ProblemsDMYKNo ratings yet

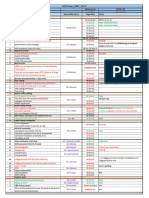

- Hach - MWP (Plan Vs Actual) Status - 22 Oct-1Document1 pageHach - MWP (Plan Vs Actual) Status - 22 Oct-1ankit singhNo ratings yet

- Ayesha Ali: 2Nd Year Software Engineering StudentDocument1 pageAyesha Ali: 2Nd Year Software Engineering StudentShahbazAliRahujoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Customer Knowledge Management (CKM) in Improving Organization-Customer RelationshipDocument7 pagesThe Role of Customer Knowledge Management (CKM) in Improving Organization-Customer RelationshipAbdul LathifNo ratings yet

- Hidden FiguresDocument4 pagesHidden FiguresMa JoelleNo ratings yet

- 131101-2 Gtu 3rd Sem PaperDocument4 pages131101-2 Gtu 3rd Sem PaperShailesh SankdasariyaNo ratings yet

- Indira Gandhi Apprentice FormDocument3 pagesIndira Gandhi Apprentice FormDevil Gamer NeroNo ratings yet

- Pierre Jeanneret Private ResidencesDocument21 pagesPierre Jeanneret Private ResidencesKritika DhuparNo ratings yet

- Performance APDocument29 pagesPerformance APMay Ann100% (1)

- Yangon Technological University Department of Civil Engineering Construction ManagementDocument18 pagesYangon Technological University Department of Civil Engineering Construction Managementthan zawNo ratings yet

- Solar Geometry FinalDocument17 pagesSolar Geometry Finalsarvesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Indian Knowledge SystemDocument7 pagesIndian Knowledge Systempooja.pandyaNo ratings yet

- Cherrylene Cabitana: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesCherrylene Cabitana: ObjectiveMark Anthony Nieva RafalloNo ratings yet

- Unit 13. Tidy Up!Document10 pagesUnit 13. Tidy Up!Nguyễn Thị Ngọc HuyềnNo ratings yet

- Electric Charges & Fields: Chapter-1 class-XIIDocument20 pagesElectric Charges & Fields: Chapter-1 class-XIIMohit SahuNo ratings yet