Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ijissh 030604

Uploaded by

pro officialOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ijissh 030604

Uploaded by

pro officialCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

Life worlds of the bidi workers in Murshidabad district of West

Bengal: A qualitative assessment

Selim Jahangir

Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi

Abstract: Bidi manufacturing is a highly labour intensive unorganised sector where women and girl children are

mainly involved in bidi rolling. On the other hand, men are mostly involved in sorting, checking, baking, labelling,

wrapping and packing where they get higher wages than bidi rollers. This paper intends to explain the limited and

confined lifeworlds of the bidi workers in Murshidabad district of West Bengal. Though they are involved in bidi making

sector with minimal wages for generations, there is no shift of occupational structure. Most of the bidi rollers are

having low socio-economic status and living in poor housing condition. Due to exposure to the tobacco there is

hazardous health condition of the bidi workers particularly the women and young girl children.Based on the in-depth

interviews in Jangipur block of Murshidabad district of West Bengal, this qualitative study aims to bring out the

insights of the everyday life worlds of the bidi workers. Besides, this study also employed non participatory observation

to bring out the ground reality of their everyday social lives. The study found that the bidi workers are being exploited

and are in perpetual poverty due to their lack of education, unemployment and under-employment, less mobility and

socio-religious practices. However, more and more public as well as Non-Government Organisations (NGOs)

interventions are necessary for their socio-economic and occupational upliftment.

Keywords: Bidi Workers, Unorganised Sector, Lifeworlds, Women and Children, Qualitative Method.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bidi sector is an informal, unorganised, home-based high labour intensive manufacturing industry in India. This

traditional agro-forestry based industry provides large number of workers in India, after agriculture, handloom and

construction (Government of India, 1995).This sector encompasses workforce involved in the collection and

processing of the two main raw materials, tendu (bidi wrapper) leaves and tobacco.Government sources have

estimated that there were about 5.5 million workers in the bidi rolling industry spreading over 16 states, majority

of who are home based women workers (Ministry of Labour and Employment Report 2001).But trade unions claim

that there are over 7 million bidi workers. However, the Standing Committee on Labour, Ministry of Labour and

Employment (2005) reported that there are about 4.5 million workers engaged in bidi industry in India with largest

number in Madhya Pradesh (18.3 %), followed by Andhra Pradesh (14.4 %) and Tamil Nadu (13.8 %)(Dube and

Mohandoss, 2013).

Bidi industry is spread across the country but mostly located in states like Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Andhra

Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Karnataka in India. Bidi manufacturing units are also found in in

Gujarat, Kerala, Orissa, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Assam. Most of the bidi making work is carried out in rural and semi-

urban areas under the contractual, homebased, piece rate system. However, the making activities vary from place to

place in terms of size of bidi, gender and child composition of workers and so on (Giriappa, 1987; Prasad and

Prasad, 1985). Most of the bidi rolling workers belong to weaker socio-economic groups with poor household;

usually having no other means of sustainable employment. Women and children are predominantly involved in this

bidi rolling activities accounting for around 90 per cent of all homebased workers.The bidi rolling is primarily

carried by Schedule Castes (SC) and Muslims OBC who lost their traditional source of livelihood (weaving, potteries

etc.). Muslim women dominate the bidi rolling activity because of socio-cultural structure considering it as the most

acceptable ‘home-based’ work (Bhatty1987; Koli 1990; Mohandas and Kumar, 1992; Gopal, 2000).

2. BIDI-A BRIEF HISTORY

The word bidi is derived from ‘beeda’ (a word in Marwari – a dialect of Hindi predominantly spoken by the trader

caste from Marwar of Gujarat and Rajasthan), which is a betel leaf-wrapped offering of betel nuts, herbs and

© 2018, IJISSH Page 21

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

condiments. The beeda is a symbol of esteem, and display of respect and reverence across the Indian subcontinent,

and the bidi gradually started being equated with it. The Indian medicinal systems, especially Ayurveda, also

prescribe inhalation of the fumes of medicinal herbs, rolled in leaves. The myth of tobacco’s medicinal properties

along with parallels in Ayurveda, led to easy acceptance of the bidi in sub-cultures.

There is no historical record of the exact period during which the practice of smoking tobacco rolled in leaves

started in India. The cultivation of tobacco started in southern Gujarat in the late 17th century. Hookah smoking

was popular among local people. Men of the same caste or sub-caste gathered around in the evenings to share a

common hookah. Because the hookah was tedious to carry around, a cheaper and portable form of the hookah was

developed, called the chillum. Bidis were developed soon after, possibly around the Kheda and Panchamahal

districts of Gujarat, where cultivation of tobacco was high. Labourers would roll leftover tobacco in leaves of the

astra tree (Bauhinia variegata) and smoke at leisure. Communities across India experimented using leaves of

mango (Mangiferaspp.), jackfruit (Artocarpusspp.), banana, sal (Shorearobusta), pandanus (Pandanusodoratissimus,

kewda) and palash (Buteamonosperma). Initially, communities in Gujarat made bidis only for their own

consumption, but their increasing popularity inspired some to make it into a home-grown business. Soon bidis

made locally became more popular than hookahs, largely because bidis overcame the obstacle of sharing the

hookah, as individuals could smoke without hurting caste and religious sentiments, and also because they were

portable and did not require assembling and extensive preparation to light up. The early business model of the bidi

industry in Gujarat involved the businessmen and their workers rolling their own bidis, putting them in a thali

(tray) and selling them along with tobacco and matches in local haats (weekly markets). Gujarati families that had

settled down in Bombay saw the potential of the bidi business and soon started manufacturing bidis on a larger

scale. Bidis penetrated into other parts of the country outside of Bombay, but until 1900 bidi manufacturing was

largely restricted to Bombay and southern Gujarat. It was during the severe drought of 1899 in Gujarat, which

compelled many families to migrate in search of a livelihood that the bidi become a small-scale industry.

When it was discovered that Leaves of Tendu tree are the best for making bidis, the bidi industry became an

important and widespread cottage industry in urban shanties and rural areas. Tendu was found abundantly around

the degraded forests of Jabalpur, and was far better than astra leaves. The tendu tree grows in the degraded

deciduous forests of peninsular India. More importantly, tendu leaves were widely available soon after the tobacco

crop was ready and cured, when most other trees had shed their leaves. The tendu leaves have all the

characteristics of an excellent wrapper material – they are large and pliable, and do not crack on rolling when dry;

their leathery texture was more acceptable than the veins and rough textures of other leaves; and they matched

well with the taste of tobacco, without interfering with the tobacco flavour.

Bidi rolled in tendu leaf soon found wide consumer acceptance. The rapid expansion of the railways in Central India

in 1899 opened new tobacco markets to this region. Between 1912 and 1918, the rapid expansion of the railways

established more such clusters in Vidharba, Telangana, Hyderabad, Mangalore and Madras. The bidi cult rapidly

spread to all parts of the country, gaining a strong foothold in the informal urban and rural economies. The habit of

smoking trickled down from cities and towns to remote villages with the development of the railways. While new

clusters were being created rapidly, several old clusters like Vidharba dissipated. Even strongholds like Madhya

Pradesh, which accounted for more than half the bidis produced till the 1980s, have lost out to new epicentres of

bidi rolling like West Bengal where labour is cheaper.

3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In the above mentioned context the present study intends to address the following research questions:

a. How the bidi workers are confined in their limited life worlds in that particular setting?

b. Why they work in bidi industry and are not shifting other work force?

4. OBJECTIVES

The main purposes of this study are

a. To look into the everyday life world of the bidi workers.

b. To examine the reasons of their perpetual poverty.

© 2018, IJISSH Page 22

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

5. DATA SOURCES AND METHODS

This qualitative study is based on primary data collection. The data were collected through in-depth interview

method. 6 in-depth interviews were conducted with the help of in-depth interview guide. A semi-structured

questionnaire was prepared for the interview. The semi-structured interview method has been used because it

allowed some flexibility to the ordered questions according to the issues from the respondents. This technique is

very helpful to fulfil the objectives of mapping life worlds of the bidi worker’s community.

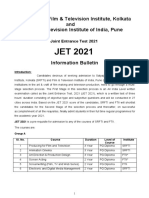

Fig 1: Flowchart of interview method.

In addition to it, non-participatory observation technique was also employed for the insight information. Besides,

metal mapping was conducted to get expressions and opinions of social behaviour from different respondents.

Study area has been shown through a map prepared with ArcGIS 10.1 software.

All the in-depth interviews were transcribed and then translated into English. The interview documents were

analysed with the weft QDA, a software tool for the analysis of textual data such as interview transcripts, field notes

and other documents.

6. STUDY AREA

Murshidabad district of West Bengal has been selected as the study area for the research. The main reason of highly

concentration of bidi workers in this region is that there is availability of low waged women workers. The whole

region is dominated by the Muslim community and they are poor, less educated and engaged in manual labourer for

their livelihood. Murshidabad is home to many of the big bidi companies and has the largest number of bidi workers

in the state. At present, the Jangipur subdivision in Murshidabad is a very sought after area for bidi manufacturing.

Selected Block for the Study:

Jangipur is the northern most sub-division of Murshidabad district. Dhulian Municipality, where the largest bidi

manufacturer of the district, i.e. ‘502 Pataka’, is located in this particular division only. Thus, Samsherganj block,

where Dhuliyan Municipality is located, is the selected block for the study where substantial proportion of

population engaged with the bidi industry. There, the total bidi rolling population in Murshidabad is about 0.6

million, of which about 90% of the workers are women and children. Among the women bidi workers about 72%

belong to the Muslim community.

Source: The author

© 2018, IJISSH Page 23

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

7. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The lifeworlds and everyday geographies of the bidi workers centred around the world of bidi making activities.

The literal meaning of the term ‘lifeworld’ is "as lived" prior to reflective representation or analysis. In other words,

the ‘lifeworld’ is a grand theatre of objects variously arranged in space and time relative to perceiving subjects. The

lifeworld can be thought of as the horizon of all our experiences, in the sense that it is that background on which all

things appear as themselves and meaningful. The lifeworld cannot, however, be understood in a purely static

manner; it isn't an unchangeable background, but rather a dynamic horizon in which we live, and which "lives with

us" in the sense that nothing can appear in our lifeworld except as lived.

The life worlds of the bidi workers are confined within their everyday activities; they occasionally access beyond

their limited social spaces. This is because of their nature of works that compel them to intact that space. As one of

the participants while explaining the everyday life and accessibility to social spaces expressed that

“After getting up in the early morning I sit for cutting leaves up to 8 or 9 o’clock. Then I pack the leaves for rolling bidi.

Then I go for market and after that I sit for rolling bidi. I rolled up to evening then go for submitting bidi to karkhana.

Then I go market for nothing and after coming back I sit for rolling bidi. We cannot keep relation with the high class

people who are engaged in services and business. They have different world and have different attitudes towards us.

We have to live within ourselves. Once one becomes rich, we cannot maintain the earlier relation. Still our society is

good and cooperative because all people in harmony. if someone falls sick other people help him as people think that all

are poor and they have to live together”.

This is the situation of most of the bidi workers in that particular setting. The everyday life worlds of women are

more limited than men. Men sometimes go for local club (a single roof building for gathering of local people for

entertainment like playing carom and cards) whereas women do not have access that spaces as well. However, the

life worlds of the bidi workers can be frames as below.

Fig 2: Life worlds of the bidi workers

Source: the author

The major reasons of rolling bidi are illiteracy and ignorance, unemployment and under-employment, poverty,

indebtedness, lower rates of wages, in adequate social security, agrarian social structure, lack of basic facilities and

amenities such as education system, health services etc. However, bidi making has different sections of works. The

division of labour or mode of employment has four categories based on the status of the work viz. (i) bidi checkers

(ii) bidi labeler/ packers (iii) helper and (iv) bidi rollers. All four types of occupation do not carry similar earning

potentials. For instance, the maximum average daily earning of labeler/packer is 42% higher than the maximum

average daily earnings of bidi rolling workers. Even, the male participation rate is higher in the first three types

© 2018, IJISSH Page 24

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

which considered being higher in post having higher earnings prospects. The whole bidi making process and spaces

used can be tabulated as below:

Table 1: Different activities for Bidi industry and concerned spaces used by workers.

Activities Spaces Work done by

Bidi Rolling a) ‘varanda’ or corridor, beneath the tree. a) Women and their daughter.

b) In some shadow place outside the home. b) Young men and boys.

Distributing raw materials and a) Corridors or ‘Baithakkhana’ of their own houses. ‘Merchen’. (Middle men)

colleting bidi from bidi rollers b) In a particular shadow place of other houses in the village.

Bidi checking with helpers In factories Specially trained men.

Bidi baking In houses of people and ‘vattis’ of particular company. Men and boys.

Bidi packing In factories Men and boys.

Women have contributed to the bidi sector right from its inception till date and also for the continuous

improvement of the sector. The working hours are very high, and they spend 14- 16 hours a day earning income to

support their families. The wages they receive is less than the wages set by the minimum wages act. The women

were less aware on the claims against health insurance, loan allowance provident fund which adds benefit to the

bidi sector. The women being home based workers do not claim for better working conditions. There is no

considerable investment made by the bidi industry on such labour force. The women supply a continuous and

stable work force to industry. The work is learnt by every member of the family and thus continues without

interruption. Since bidi employs large numbers of women workers, it adopts exploitative practices which affect

women workers in general. The home workers are exploited more since they have no operative trade union forum

as in the organized sector.

8. CONCLUSIONS

It has been observed that most of the bidi workers are drawn from low castes like scheduled tribes, more from

Muslims and a very small percentage of poorer sections from the general castes. The inadequate income, various

unauthorized deductions, less payment than the agreed wages, etc. degraded the socio-economic status of bidi

workers. Moreover, bidi workers, more particularly those who are working in the informal/unorganised sector, are

facing many problems. There is a wide gap, from the point of view of benefits, between the bidi workers in the

organized sector and those in the unorganized sector. Some of the problems that bidi workers face are

1. Low wages of payment which is, usually, under piece rate system and the piece rate is very low.

2. Exposure to tobacco related health hazard.

3. Superior strength of employer and this strength is used to exploit the poor bidi workers.

4. Inadequate social security.

5. A poor growth of Trade Union movement.

However, the governments (both the central and state governments) have made some attempts to protect the

interest, and for the welfare, of bidi workers in the form of enacting Laws, establishing boards to give effect to the

policy decisions of the governments, etc. The most surprising and unfortunate thing is that bidi workers themselves

are not aware of their legal rights and privileges. Despite various security legislations, the socio-economic condition

of the bidi workers in the unorganized sector has not improved. On the other these poor bidi workers are being

exploited by the powerful employers and by their agents/contractors.

REFERENCES

Bhatty, Z. (1987). Economic contribution of women to household budget: A case study of the beedi industry. In

Invisible hands: Women in home-based production, edited by Andrea Menefee Singh, Anita Kelles-Viitanen,

35–50. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Dube, Y. and Mohandoss, G. (2013). A Study on Child Labour in Indian Beedi Industry, National Commission for

Protection of Child Rights.

© 2018, IJISSH Page 25

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities

(IJISSH)

ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 6 | June 2018

Giriappa, S. 1987. Beedi-rolling in rural development. Delhi; Daya Publication. pp. 128.

Gopal, M. (2000). Health of women workers in the beedi industry. Medico Friends Circle Bulletin (JanFeb)

http://www.mfcindia.org/mfcpdfs/MFC268-269.pdf

Government of India. (1995). Unorganised Sector Services: Report on the Working and Living Conditions of

Workers in Beedi Industry in India, Ministry of Labour, New Delhi.

Koli, P. P. (1990). Socio-economic conditions of female beedi workers in Solapur district. Social Change, 20(2):76-81

Ministry of Labour. (2001). Annual Report 1999-2000, page 109.

Mohandas, M., and Kumar, P. V. (1992). Impact of Cooperativisation on Working Conditions: Study of Beedi Industry

in Kerala. Economic and Political Weekly XXVII (26): 1333–38

Prasad, K. V. E. and Prasad, A. (1985). Beedi workers of Central India: a study of production process and working

and living conditions. Noida: The Institute. Pp. 196.

© 2018, IJISSH Page 26

You might also like

- The Beedi Industry in India: An OverviewDocument41 pagesThe Beedi Industry in India: An OverviewBest Practices Foundation100% (1)

- 08 Chapter 01 (Beedi Industry)Document27 pages08 Chapter 01 (Beedi Industry)asih hkasaNo ratings yet

- Development of Beedi Industry in Murshidabad District (1950 - 2020)Document5 pagesDevelopment of Beedi Industry in Murshidabad District (1950 - 2020)・Sαγҽɳ࿐ ・No ratings yet

- 7 EconomicImportanceofJuteDocument14 pages7 EconomicImportanceofJutesattom halderNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Condition of Kanshari CommunityDocument16 pagesSocio-Economic Condition of Kanshari CommunitySezan Tanvir0% (1)

- Haat An Instrument of Cultural, Social, Economic and Political SocializationDocument6 pagesHaat An Instrument of Cultural, Social, Economic and Political SocializationResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Cash Crops of Bangladesh: BPH101: Bangladesh Political HistoryDocument8 pagesCash Crops of Bangladesh: BPH101: Bangladesh Political Historywasiul hoqueNo ratings yet

- Ensuring Traditional Handicraft Promotion To Sustain Tribal Livelihoods: A Case Study of Kisan Tribe in Sundargarh District, OdishaDocument5 pagesEnsuring Traditional Handicraft Promotion To Sustain Tribal Livelihoods: A Case Study of Kisan Tribe in Sundargarh District, OdishaDebasish PradhanNo ratings yet

- Ensuring Traditional Handicraft Promotions To Sustain Tribal Livelihood: A Case Study of Kisan Tribe in Sundargarh District, OdishaDocument5 pagesEnsuring Traditional Handicraft Promotions To Sustain Tribal Livelihood: A Case Study of Kisan Tribe in Sundargarh District, OdishaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- X DissertationDocument68 pagesX DissertationRahul MajumderNo ratings yet

- Beedi IndustryDocument69 pagesBeedi IndustryBargavi NarayananNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Structure and Amp SustainDocument7 pagesSocio Economic Structure and Amp SustainJatin Singh AryaNo ratings yet

- Employmnet To Women in Indian Beedi Indutry An Opportunity or Threat: "A Case Study of Nizamabad District"Document10 pagesEmploymnet To Women in Indian Beedi Indutry An Opportunity or Threat: "A Case Study of Nizamabad District"kumardattNo ratings yet

- Sociological AnalysisDocument31 pagesSociological AnalysisAbdul Rafay NawazNo ratings yet

- Historical Tradition and Socio-Cultural Transformation of The Malakar Community in Rural Bengal, IndiaDocument11 pagesHistorical Tradition and Socio-Cultural Transformation of The Malakar Community in Rural Bengal, IndiaKousik D. MalakarNo ratings yet

- Historical Evolution of Agricultural LabourDocument6 pagesHistorical Evolution of Agricultural LabourNivedha SundharalingamNo ratings yet

- Peerzadoetal Ijds 7 2Document10 pagesPeerzadoetal Ijds 7 2muhammad irsyadNo ratings yet

- Problems of Beggars: A Case Study: January 2013Document9 pagesProblems of Beggars: A Case Study: January 2013skarthiphdNo ratings yet

- Critically Analyse The "Civilizational Challenges" of COVID-19 in IndiaDocument7 pagesCritically Analyse The "Civilizational Challenges" of COVID-19 in IndiaSuyash GoenkaNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2007558Document7 pagesIJCRT2007558Amitrajit BasuNo ratings yet

- Juili Bhadari - SYBA - B - 20 - Sociology - 2Document18 pagesJuili Bhadari - SYBA - B - 20 - Sociology - 2Your ProjectNo ratings yet

- DemographyDocument7 pagesDemographyAyushi BhattNo ratings yet

- What Is Rural?Document9 pagesWhat Is Rural?Roon SenNo ratings yet

- Impact of Forest On Socio Economic Development of Tribals in Balaghat DistrictDocument8 pagesImpact of Forest On Socio Economic Development of Tribals in Balaghat DistrictEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- DevelopmentAmong-1 1 PDFDocument13 pagesDevelopmentAmong-1 1 PDFLeonard Ayson FernandoNo ratings yet

- Issues and Problems in Agricultural Development: A Study On The Farmers of West BengalDocument13 pagesIssues and Problems in Agricultural Development: A Study On The Farmers of West BengalLeonard Ayson FernandoNo ratings yet

- Market Access of Bangladesh's Jute in The Global Market: Present Status and Future ProspectsDocument10 pagesMarket Access of Bangladesh's Jute in The Global Market: Present Status and Future Prospectsshahadat hossainNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Impact of Cordyceps Collection On Cordyceps Collectors in Sephu Gewog of BhutanDocument8 pagesSocio-Economic Impact of Cordyceps Collection On Cordyceps Collectors in Sephu Gewog of BhutanInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- IJAEPaperDocument10 pagesIJAEPapernazmaira523No ratings yet

- Patachitra-A Micro Scale Industry: Overview and Challenges: Subhamoy Banik, Utpal KunduDocument6 pagesPatachitra-A Micro Scale Industry: Overview and Challenges: Subhamoy Banik, Utpal KunduTanima GuhaNo ratings yet

- Sociology Paper-Ii: Comprehensive Course On Optional FOR UPSC CSE 2020/2021 Paper-2 Tribes in India-IiDocument18 pagesSociology Paper-Ii: Comprehensive Course On Optional FOR UPSC CSE 2020/2021 Paper-2 Tribes in India-IiNaga Siddhartha VemuriNo ratings yet

- GOONJ1 PDFDocument19 pagesGOONJ1 PDFsantosh muragodNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Satranji RangpurDocument10 pagesChapter 2 Satranji RangpurSharif Shariful Islam100% (1)

- A Study On The Present Condition of The Weavers of Handloom Industry: A ReviewDocument8 pagesA Study On The Present Condition of The Weavers of Handloom Industry: A ReviewKavi Prasath RNo ratings yet

- RURAL SOCIETY and DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA TDocument6 pagesRURAL SOCIETY and DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA Tyociped339No ratings yet

- Impact of Globalisation On Rural Odisha: ChallengesDocument5 pagesImpact of Globalisation On Rural Odisha: ChallengesAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.40.196.176 On Sun, 10 Apr 2022 07:12:23 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.40.196.176 On Sun, 10 Apr 2022 07:12:23 UTCpaapoonNo ratings yet

- 2470-Article Text-3230-2-10-20190424Document12 pages2470-Article Text-3230-2-10-20190424Arifin Bin WafirNo ratings yet

- Rural Visit ReportDocument16 pagesRural Visit ReportPrachi VermaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Status of Female Workers Engaged in Traditional Chikankari Under Sitapur DistrictDocument7 pagesSocio-Economic Status of Female Workers Engaged in Traditional Chikankari Under Sitapur DistrictAsian Journal of Basic Science & ResearchNo ratings yet

- Fashion Outputon Khadiin Bangladesh AReviewDocument24 pagesFashion Outputon Khadiin Bangladesh AReviewZarin Tasnim RezaNo ratings yet

- Issues and Problems in Agricultural Development: A Study On The Farmers of West BengalDocument13 pagesIssues and Problems in Agricultural Development: A Study On The Farmers of West BengalParth PandeyNo ratings yet

- Alternativeemploymentfor Beedi WorkersDocument37 pagesAlternativeemploymentfor Beedi Workersashwini arulrajhanNo ratings yet

- IJRCS202105010 FullarticleDocument7 pagesIJRCS202105010 FullarticleSai SiddharthaNo ratings yet

- Status of Agarbatti Industry in India With Special Reference ToNortheastDocument15 pagesStatus of Agarbatti Industry in India With Special Reference ToNortheastPRANAV W 32No ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Indian Textile Industry: An Insight Into Inclusive Growth and Social ResponsibilityDocument10 pagesA Critical Analysis of Indian Textile Industry: An Insight Into Inclusive Growth and Social ResponsibilityJanhavi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Gondi 4Document7 pagesGondi 4Environment bellampalliNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument47 pagesChapterThe Style ProjectNo ratings yet

- 2018 DahlanDocument11 pages2018 Dahlanbikincv40No ratings yet

- Formate - Hum - "A Historical Case Study On Hat Tola Movement in Jalpaiguri District in Pre - Independence India"Document6 pagesFormate - Hum - "A Historical Case Study On Hat Tola Movement in Jalpaiguri District in Pre - Independence India"Impact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health Problems Faced by Female Beedi Workers at Khajamalai, Trichy District, Tamil NaduDocument6 pagesOccupational Health Problems Faced by Female Beedi Workers at Khajamalai, Trichy District, Tamil NaduS.SRINIVASANNo ratings yet

- Article On Dungaria Kondh-IJCRTDocument8 pagesArticle On Dungaria Kondh-IJCRTkrishnakumarsnairNo ratings yet

- IJCRT1133950Document3 pagesIJCRT1133950Jeetendra MeherNo ratings yet

- Ecobiz Newsletter III IssueDocument4 pagesEcobiz Newsletter III IssuerutwikdphatakNo ratings yet

- Status of Agarbatti Industry in India With Special Reference To NortheastDocument15 pagesStatus of Agarbatti Industry in India With Special Reference To NortheastAkash KumarNo ratings yet

- Marginal Occupations and Modernising CitiesDocument11 pagesMarginal Occupations and Modernising CitiessuedesuNo ratings yet

- Public Policy For The Future of Primitive Tribes in The Suku Anak Dalam, Jambi-IndonesiaDocument21 pagesPublic Policy For The Future of Primitive Tribes in The Suku Anak Dalam, Jambi-IndonesiaRandi KhampaiNo ratings yet

- Sericulture Industry in India - A ReviewDocument27 pagesSericulture Industry in India - A ReviewNaveen Kamat100% (1)

- Folklore of Munda Tribe in OdishaDocument4 pagesFolklore of Munda Tribe in OdishaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- IJCRTDRBC078 HowtomDocument9 pagesIJCRTDRBC078 Howtompro officialNo ratings yet

- Carpet Weaving BhadohiDocument53 pagesCarpet Weaving Bhadohipro officialNo ratings yet

- Information Bulletin JET2021Document7 pagesInformation Bulletin JET2021BROZ CreationsNo ratings yet

- Wooden Mask1Document28 pagesWooden Mask1pro officialNo ratings yet