Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fernando Sor Seguidillas PDF Free

Fernando Sor Seguidillas PDF Free

Uploaded by

Lionel Andrés Messi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views59 pagesSeguidillas Sor

Original Title

fernando-sor-seguidillas-pdf-free

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSeguidillas Sor

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views59 pagesFernando Sor Seguidillas PDF Free

Fernando Sor Seguidillas PDF Free

Uploaded by

Lionel Andrés MessiSeguidillas Sor

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 59

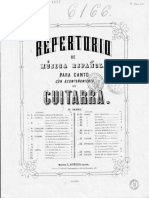

FERNANDO SOR

SEGUIDILLAS

for voice and guitar or piano

| : ‘ 5 ey

: BRIAN JEFFERY

Cow atte

FERNANDO SOR

SEGUIDILLAS

for voice and guitar or piano

edited by

BRIAN JEFFERY

TECLA EDITIONS

SOAR CHAPEL - PENDERYN

SOUTH WALES - GB-CF44 93¥

Tecla Editions,

My warm thanks are due to the Anglo-Spanish Cultural

Foundation for a Vicente Cafiada Blanch Secior Research Fellow

ship which enabled me to carry out research on Sor. Also to

Robert Spencer for allowing the publication of songs in a manux

seript in his collection; to the British Museum for similar

pennission; and to Roger Boase for valuable assistance with the

texts

‘Any of these songs may be performed in a public concert

without formalities, provided that the concer: is not recorded and

that the programme bears the words ‘From Sor’s Seguidillas,

edited by Brian Jeffery (London, Tecla Editions, 1976). All other

rights, including all kinds of recording ard broadcasti

reserved.

Reprinted 1983. This reprint incorporates no new material; but to

misprints have been corrected, and the opportunity has been taken to

improve the legibility of the facsimile of Sor’s important article

‘Le Bolero’,

Reprinted 1990

© Brian Jeffery 1976.

ISBN: 0 906053 01 4

Photocopying this edition is illegal.

CONTENTS

Inteoduetion

ditorial practice

Notes to the songs

esa de atormentarme

De amor en las prisiones

Acuérdate, bien mio

Prepirame la tomba

Como ha de resolverse

Muchacha, y la vergiienza

Si dices que mis ojes

Los eandnigos, madre

EL que quisiera amando

Si a otro cuando me quieres

Las mujeres y cuerdas

Mis descuidados ojos

Facsimiles of nos. 2 and 9

Facsimile of Sor’s article “Le Bolero’, from the

Encyclopédie Pittoresque de la Musique of

‘A. Ledhuy and H. Bertini (Paris, 1835)

Page

12

13

INTRODUCTION

Hone are twelve songs in Spanish by Fernando Sor (1778-1839)

nine with guitar accompaniment, two with piano, and one with

tither guitar or piano. Sor is known today for his guitar music,

but until now almost no songs by him have been published in a

modlern edition. Yet, he composed many different kinds of songs:

Spanish patriotic songs, English theatre songs, Italian arietts,

French romanees, and— these Spanish seguidillas. Antonio Petia

y Goni heard some of them sung in Paris by the famous Catalan

Singer Lorenz Pagans, and wrote:

Por mi parte, he ldo varias canciones espaiiolas,

originales de Sors, cantadas por Pagans en Paris y puedo

ascuurar que la originalidad y frescara de la melodia, el

nterés arménico y Ia viveza del ritmo aventajan con mu-

cho las de Manuel Garcia € Iradier. Débense sobre todo

4 Sors aligunos boleros que son verdaderas joyas.*

(For my past, I have heard a number of Spanish songs,

Driginal works of Sor, sung by Pagans in Paris, and 1 can

E ig by Pag

‘Antonio Petia y Gani, La dpere espefiola y la misica dram:

Fapoia en el siglo XIX (Madesl, ISB1), pp. 13L2. Two pictures by

showing Pagans singing and accompanying himself on tho guitar are

reproduced W's The Art and Times of tho Guiter (London,

1968), pp. 244-5

ear witness that the

jginality and freshness of the

melody, the harmonic interest and the vivacity of

the rhythm, are much superior to those of Manuel Gar-

cia and of Iradier. Above all we owe to Sor some boleros

which aro veritable jewels.)

What exactly are seguidillas (or boleras)? One of our most

important sources of information is an article by Sor himself,

called “Le Holere’, which he wrote for the Encyclopédie Pitto

resque de la Musique of A. Ledhuy and H. Bertini (Paris, 1835).

‘This article is reproduced in facsimile at the end of the present

edition. In it, Sor begins by explaining how seguidillas are related

to the bolero. A seguidilla is a type of poem, which may be

set to music. If it is set in such a way as to suit the dance known

as the bolero, it is called a soguidilla bolora or seguiclilias boteras

(or simply, in the musical sources, boleras or voleras). This is the

terminology used in Spain before the French invasion of 1898,

ani it is the terminology used in this edition. However, outside

Spain after the invasion, the one word that everyborly knew was

“bolero’, and this is why Sor called his article “Le Bolero’, why

elsewhere he called his own songs boteros rather than seguidillas,

and why Peia y Goni in 1881 also called them boleros. It is

penedpally a later usage rather than the original one.

Sor sets out the history of the dance, the bolero. The first

seguidillas that were danced to, he says, were Seguidillas Man-

‘chegas (j., from La Mancha), ‘a cause de lear mouvement plus

vite que celui des Murcianas, et surtout des Sevillanas'. This dance

‘was adopted by the “bas peuple’. Then a young man nicknamed

bolero, ‘the flyer’, because of his agility, added faster steps and

in order to fit them in used the slower music of the Seguidillas

Murcianas, while still (says Sor) beginning his dance with eight

Das of the Manchegas. The dance was named, after him, the

bolero. ‘This form of the dance became very popular, espectall

in theatres, where it was danced during ihe cntactor as Gi

witnessed in Barcelona in 1797. But it soon became very com:

plex, grotesque, even lascivions, and fell out of Fashion; yet at

the same time the songs that were associated with it becan

more favoured:

Au fur et & mesure que cette danse perdait de sa

vorgue, les Segnidiflas que Ton y chantait furent général

ment adoptees, ct clks_ sont” encore jour iui a. Ja

mode, sons le nom de Boleros ou Seguidillas Boleras.

(AL the sume time as this dance lost its popalarity, the

Sounidlillas that were sung to it eame to De generally

adopted, and they are still fashionable today, under the

name of Boleros or Seguidilles Boloras'.)

This passage is important because this is the stage fo which Sor's

seguidillas in this edition probably belong.

“The next step (says Sor) was the rehabilitation of the dane

about 1801, by a dancer named Requejo. He is said to have

come from Murcia. He made it slower, more dignified and

graceful, and replaced the guitar with a small orchestra. This

was the form of the holero that

vogue when the French,

lancers had fled, and those

aban Calderiny

‘agrees with thi and says the

thin Covezo from La Mancha or A

theories about the origin of the name bolero have been achanced; see, for

instance, the article ‘Bolero’ in the Enciclopedia Universal Europeo-Ame

‘or himself composed “boleros! in Barcelona that were performed in

fan entacle (Diario de Barcelona, 10 Decomber 1798), But whether these

‘ete instrumental music or songs i mnt elear,

'S Katchaner Calderin, Excrnas andaluzes, p, 28,

who remained snd danced for the invader added gipsy steps to

TeThe Frensh alded sowie ol the ofie; en Gi Halo’ that

conquered Burope was unrecognizable,

M. Conlon a éprowvé plus de difficulté A instruire

‘mademoiselle Mereandotti. Espagnole [the famous dane-

fer], qui dansait deji le Bolero dans Ie veritable genre

caractéristique, que si elle n'et jamais rien appris.

(ML. Coutlon tad move difficulty in teaching, Mlle Mes-

eandotti, who as a Spaniard already daneed the Bolero

inn the characteristic style, than if she had never learned

anything at all.)

In the same Encyclopédie is a biography of Sor, written in the

third person but in such detail that it was almost certainly he

who wrote it. From this we learn that he composed “boleros’ in

Bareelona in about 1802-3 and in Madrid in about 1803-4, where

they were much in demand. This coincides exactly with the sta

ment above, that after about 1797 seguidillas boleras became

very popular in Spain while at the same time becoming dissociated

from tho dance, and very probably this is the stage to which

mist of the songs in this edition belong, They are related to the

dance yet independent of it. They can hardly date from before

about TIT, when Sor as a young man of nineteen was just

beginning his career as a composer in Barcelona; ancl (except for

no. 12) they certainly date from before his exile in 1813. Therefore

they are products of the late Spanish baroque, “the age of the

growth of the bullight, of the flowering of the minor arts and

Tandierafts, and above all of popular music and dance’ (Gerald

Brenan, The Literature of the Spanish People, London, 1963,

1p. 902}. It was an age in which, despite the strong influence of

talian music, the native popular tradition was vigoros and

respected. Manfred Bukofzer writes, in his Music in the Baroque

Era (London, 1948), py 175: ‘Here [in Spanish secular music of

the 17th and 18th centuries] we have one of the very few exam-

ples in baroque music in which the influence of folk music on art

music is more than wishful thinking’. Sor’s seguidillas reflect just

such an influence: they are the contibution of the greatest

{guitarist of his age to a popular tradition which is still alive today.

‘The text of a sogui ally had seven lines, and sometimes

only four. The fist four were called the copla, and the last throe

the estribillo. A strict metrical form was observed in which the

Tines always had alternately seven and five syllables. The rhyme-

scheme, however, was looser than the metre: the second and

fourth lines had to rhyme together, and the fifth and seventh, but

either rhyme or assonance would do, and the other Tines might

for might not rhyme together. Here is an example from this

edition, no. 11:

Las mujeres y euerdas

‘De la guitarra,

Es menester talento,

Para templarlas,

Flojas no suenan,

¥ suelen saltar muchas

Si las aprietan,

(Women and guitar strings: you need

talent to tune them. If they're slack they

don't sound; and lots of them, if you

tighten them too much, break’)

So short a poem, like the limerick in English or the haikw in

Japanese, must make its effect ina small space. It often does so

by playing on words. In the above example, templar refers both

to women and to guitar strings; and in no. 12, cara means “face

‘and also ‘dear, costly’, ‘The subject-matter is nearly always

amorous, Either a mood is set, generally a sad one, or a humorous

point is made. Sor says of the poems: “En effet, les paroles en

sont généralement tr2s spirituelles.

cr brevity has a long tradition behind it, going back to the

‘comat Iysies of the Spanish Renaissance, to certain medieval poems

throughout Europe, even pethaps to the very oldest of all

Romance love poems, the tiny Kharias of Moslem Spain (see, for

instance, Peter Dronke’s The Medieval Lyric, London, 1968,

Dp. 86-51}; and similar eoplas are stil being written, composed,

sung. and collected today. The imagery is traditional too. For

example, ‘Si dices que mis ojos' (no. 7) is a love lyric but uses

us terminology, just as did the Spanish Renaissance court

lyric: the woman says ‘IF you say that my eyes kill you, then you'd

Detter make confession; take the sacrament; for Tm on my

‘The music of seguidilas, like the text, is short. But repetition

is used, according to certain fixed p

musical sections, just as it had been centuries before in. the

Spanish villancico, the French rondeay, or the Italian ballata, In

Sor’s seguidillas, the repetition scheme is nearly always the same.

And the rhythm is always triple, Other musical features are char

acteristic but not invariable, Thus, within the basic triple rhythm,

triplets are common. A favourite melodic interval is the descending

augmented second: for instance, C sharp to B flat, or D sharp to

C natural. An instrumental introduction is frequent. And the

accompanying instrument most favoured is the guitar, though

the piano is also found, as in nos. 8 and 10 in this edition. In

seguidillas of this period, a solo voice is usual, though some are

duets or trios.

‘These features are found again and again in seguidillas

composed in Spain at this time. ‘They occur in seguidillas by

Moretti; in anonymous songs of a simpler and more primitive

mutations of words and

7

type than Sor's; and in more advanced anonymous ones. Bat

the situation changed. ‘The bolero caught the imagination of

Europe and became part of the Spanish aura of Romantieism,

a that produced such works ay Hugo's Hernani or Bizet’s

Carmen. Te was danced and sung everywhere in Europe, and

examples were composed and published outside Spain. by Sor

and by many others. Its popularity culminated in. the most

famous bolero of all, Ravel's Boléro for orchestra (1928), And in

the boleros published outside Spain in the nineteenth century, the

style changed. ‘The guitar yielded to the piano as the favourite

accompanying instrument; duets and trios with piano accom

ment becune more frequent; the characteristic repetitions were

abandoned; and more and more the songs betray that they are

no longer the genuine product of a culture on fis own ground,

Sor played his part in this later diffusion, by composing andl

publishing both arrangements of his old. seguidillas and what

appear to be new ones, under the name of boleros, But these

Tater songs are not included here. This is an edition of those

songs, ancl only those, which Sor composed before leaving Spain

in 113 (or within a year of leaving it) and which therefore belong,

to an anthentically Spanish tradition. The later ones are excluded,

although for the sake of reference they are listed in the Catalogue

below.

‘These early songs were distributed not in printed editions but

in manuscripts. In Spain at that time it was customary to have

music copied by 2 seribe, in an establishment called a copisteria,

and the three manuscripts used for this edition show every sign

of having been copied in this way. Though they are all’ three

now in London, they certainly originated in Spain, in one case

9, MS Egerton

about 1613 and in the others by 1819 at the Tatest. The one

printed edition that has been used (for no. 12) was published in

Paris within a year of Sor’s arrival there in 1813. Despite extensive

search, 10 manuscripts containing seguidillas by Sor have been

Sor's sophisticated yet simple accompaniments. respeet and

jcately. support the texts. They show an awareness amd ap-

preciation of these elegant, brief, and witty poems. The maning

‘uiplets in ‘Las mujeres y euerdas’ (no. 11) gradually nse to sug,

gest the idea of tuning a guitar (or, in this poem, a woman); and

the repeated bass notes and arpeggios in Muchacha, y la ver

_gienza’ (vo. 6) are appropriate to that grotesque poem, The

iceompaniments are generally for guitar, and in only two known,

‘eases for piand (00. 12 has altemative guitar and piano aceon

ptniments). When performing the songs. it is important to

remember that in the early nineteenth century” the piano

‘yas lighter in tone than it is today, and that the guitar wa

smaller, lighter in tone, and gutstrung

How far are Sor's seguidillas original compositions, andl how

far arrangements of popnlar songs? We cannot know the full

answer without much more research on this neglected period,

bat the evidence suggests that the concept of originality is not

relevant to this still pre-Romantie period. Sor took his phice

uuithin a tradition, rather than asing its materials to make entively

new compositions. The various different versions that are knowin

of his songs demonstrate this fact. Someti

Jnown in which the words are the same but the music different

(vos. «4 and M1); sometimes versions in whieh the musie is the

same but the words different (nos. 2 and 8); and sometimes both

words and music are similar but changes have been made (no, 6

exists in a version for two voices instead of one and with piano

accompaniment instead of guitar). It seems that interchanges

secre made readily, that there was little attempt to preserve

this rich wadition allowed for

adaptation, Sor’s seguidillas. spring

t include anything composed after that

es pone here is a list of all his

sh arranged aceording to source: first

he present edition, and then all these later

fuscum, MSS Egerton 3288 and 3289. These are

ly Eau! mans ech Uearng on the

we words ‘CANCIONES ESPANOLAS" and

"TOM. Il" respectively, and consisting of groups

Pees ea en Te

ively, Egerton 9288 is inseribed inside the

yd

cur

los 11

words ‘Seis Voleras / Con acompatiamto, de

wing the following. group of six songs:

1, Hf, 106 verso-107.

somes’, ff. 107 vers0=108.

“Acueidate, bien mio’, ff. 108 verso-108.

‘Prepirame a tambe’, ff. 109 versc-110.

‘Cémo ha de resolverse’, Ff. 110 verso-ILL

“Muchacha, y ta verguenza’, ff. 111 verso-L12,

Pues

‘This manuscript also contains a version of a three-voice song

hy Sor; see below, Copenhagen, Royal Library, Rung Collec

tion, MS 1066.

Egerton 3285:

7. ‘Si dices que mis ojos, Hf. $8 verso-89.

London, collection of Robert Spencer. A bound manuscript bearing

-on the front cover the words ‘SPANISH SONGS j LADY

HARRIET CLIVE’ and on the spine “SPANISH SONGS’.

Oblong format, c 30 X BL em. 3H pp. Like Egerton 3388

arn! 3289, it consists of many songs and groups of songs bound

together, It is uniform in binding amd forinat with another

manuscript in the collection of the present editor, which bears

the same words on its front cover and spine. The signature ‘RIL

Clive’ appears many times in both volumes. ‘This was Robert

Henry Clive (1759-1854), M.P. for Ludlow from 1818, who in

1812.14 accompanied Lord John Russell and G.AP.H. Bridge

man (afterwards Earl of Bradford) on a journey through Spain

and other countries, Bridgeman wrote letters back to England,

which were published as Letiers from Portugal, Spain, Sicily,

‘and Malta, in 1812, 1813, and 1814 (London, 1875), and ina

letter dated from Madrid on 10 July 1813 he writes ‘L have

got some Spanish music here, which Twill send the first

‘opportunity’ (Letters, p. 120), Clive's signature in these two

volumes suggests that it was on this joumey that they were

acquired.

8. ‘Los eandnigos, made’, pp. 89-91

9. “El que quisiera amando’, pp. 93-95.

10, “Si a otro cuando me quieres’, pp. 97-99.

“Al mediator jugando’, pp. 101-103, a version of no. 2 in

this edition.

Morena de mis ojos, pp. 105-107, another version of

no. 2 in this edition.

LL. ‘Las mujeres y cuerdas’, pp. 109-111.

BOLERO DE SOCIETE / avec Accompagnement de Guitare

et Piano |) COMPOSE ET DEDIE / A S.E. MADAME LA

DUCHESSE DE ROVIGO / PAR M. FERDINAND SOR.

(Paris, Mme Benoist, nd. (1513 or 1814))

Two pages. No plate number. Copy: Paris, Bibliothéque

Nationale. A printed edition of:

12, “Mis deseuidades ojos’

SoNcs NOT IN THUS EDITION

A printed colle«

di Musica.

Contains a version for two voices and piano or guitar of no. 8

in this edition; see the notes to that song.

on of unknown ttle. Copy: Milan, Conservatorio

IMPROMTU, / dans le genre du Boléro,

Harmonie Institution, n.d. (1819)

Copy: London, British Museum.

A printed version, for two voices and piano, of no. § in this

edition; see the notes to that song.

‘A manuscript in the collection of Robert Spencer, London,

Contains a version of no, 8 in this edition; see the notes to

that song

(London, Regent's

10

Copenhagen, Royal Librar Collection, MS 1065. A manu-

scaipt apparently of the early nineteenth century. Oblong

format, ©. 36 X 25 om. Includes:

“Cuantas naves se han visto!

For three voices aud piano, in C. Headed “Bolero @ tres voces

de Sor. Four lines of text. Other versions are in London,

British Musenm, MS Egerton 3289, ff, 152 verso-154, where it

appears as an anonymous song for three voices and guitar,

in D, with words beginning ‘Mucha tierra he comidk

Centos Espaioles, for which see below.

and in

“Tres | SEGULDILLAS { Boleras / A DOS YOCES / con Acom-

ppafiamiento de Piano Forte / Compuestas / y Respetuosamente

Dedicadas / la Exma. Seiora / Duquesa de San Carlos /

por su humilde servidor / F. SOR. / PRIX 6f. | Paris, Chez,

AUTEUR, Place des Italiens, Hotel Favart / et Chez

MEISSONNIER, Boulevard Montmartte, No. 25 Ten pages.

No plate number. Copy: London, British Museum, A printed

collection of three seguidillas by Sor for two voices and piano.

Published not earlier than late 1826 or early 1827, when Sor

returned from Russia to live in Paris, andl not later than about

1892, when the publisher Meissonnier moved from 25 Bd.

Montmartre (C. Hopkinson, A Dictionary of Parisian Music

Publishers 1700-1950, London, 1954), The Duke of San Carlos,

Spanish ambassador to Paris, died on 17 July 1525, and thi

edition may well have been published before that date.

“Puede tuna buena moze’, pp. 24

“Me pregumta un amigo’, pp. 5-7

“Lo que no quieras darme’, pp. 610.

REGALO LIRICO / Coleccién de Boleras, Seguidillas, Titanas /

y Denuis Canciones Expatiolas. / Por los mejores Autores de

Andalucian Anntal for 1837 (London, 1836). Copy: London,

British Museum, A printed book including on page 23 0

i version without words of ‘No quiero, no, que vengo’ (sce

Oblon 6 Regalo Lirico above).

7

ongs by Sor, the fi os Espanoles, cd. E. Ovén (Miilaga, 1874). Copy: Madrid

‘ \ Re “nt lage,

Nacional, A printed book inchiding versions of

‘ongs by Sor, the first for three voiees and piano, and the

second for solo voice and plano.

*Yo sembré una mirada’, pp. 25-29. A version in C of “Cuantas

faves se Han visto’ (see above, Copenhagen, Royal Library,

Rung, Collection, MS 1085),

_Pa)irillo amoroso, pp. 98-43. A version of no. 7 in this edition;

see the notes to that song,

3

s, Bibliothique Nati

icle by Sor ent e

u

EDITORIAL PRACTICE

Sretanc is modemized. Punctuation, capitalization, and indenta-

tion are editorial. In this edition, 1 have printed each poem

separately before each song. In the original sources the usual

practice was to underlay only the copla (lines 1-4) and to write

the estribillo (lines 5-7) out separately. Only in nos. 8 and 9 is the

estribillo underlaid in the original sources. In no. 5 there is

no estribillo at all

All omaments and slurs are original, All accidentals and tempo

indications are original except those in brackets, which are

editorial. Obvious errors are corrected without note; all other

changes are recorded in the notes.

Sometimes when « passage recurs, there are minor differences

such as the different spacing of a chord, or the different order

of the notes in an arpeggio. [have not standardized these, though

there secms no reason why a player should not do so if he wishes.

Strict observance of these details is inappropriate to these songs.

‘The underlay of the original sources has been reproduced

exactly. Sometimes the accentuation of the Spanish is a little odd,

for instance in ne, 11 where the music implies menester instead

of menester, and performers may feel free to alter the accen-

tuation if they so wish.

T have given no fingering. The accompaniments are simple,

and any competent guitatist should be able to work out his own.

Originally the singer probably accompanied himself.

2

1¢ indication ‘Andante’ almost certainly does not mean so

slow a tempo as would usually be meant today. Its meaning is

rather ‘with movement’

In the original sources, repeats are indicated by a form of

shorthand. In the set of six seguidillas in MS Egerton 3289

(nos. 1-6 in this edition), the music of the first part is always

fully written out once more at the end, and there is always a

final bar with two heats rest and the direction ‘Al Segno’ (see

facsimile of no. 2). This final bar is to be interpreted as the final

bar of the whole piece, and the frst time through the performer

is expected to proceed without a break as he had done at the

conesponding point earlier in the song. The printed source of

no, 12 confirms that this interpretation is correct, and the tram:

scriptions of nos. 1-6 have been established accordingly. The same

is true of nos. 9 and 10. But the sources of nos. 7 and 11 are

Aifferent: they do not write ont the music of the first part once

more at the end, and there is no final bar. In this edition it has

been assumed that the repetition pattern and underlay sequence

of these two songs should be the same as in nos. 1-6, and the

transcriptions have been prepared accordingly. Final bars have

been invented for them on the analogy of nos. 1-6. No. 8 is @

special case which does not follow the usual repetition pattem

at all

In this 1983 reprint, the facsimiles of ‘De amoren las prisiones’, “PL

‘que quisiera amanda’, and Sor's article ‘Le Roléra’, are all reproduced

at actual size.

“this ghee one

i ehtnged searing, ©

f MS in the collection of Robert

rite itlo-page with the words ‘Siguidilles / Pova

Ipod a Revo Guitar soeeranncn. Te

Np recar juzando

ve ti Se

Lasriltdos yobs.

¥ ol cash ha sido,

fe Sno met Basto

Me dan Catillo.

" Kore Liwas playing “meaiater’ with three tadice,

in less tha wero. gave them xo

what happened then ‘was, that #1

i ace OF clibs, T was oat of the

“an amorous poem is full of double meanings. ‘Mediator’ is

ne Spanish cant game which wae extwomely fashenable

tho ond of the eighteenth century, The term Ombre or The

ye pity who undertakes to play aga the teat of

re was played by three persons, with a pool of counters and

vthe eight, nine, and ten being withdeawn, Mediator

sons The terminology of the game fe Spanish and.

® In Tine 3 of this poem, om menor do dor credo

itso eredos' ‘very quickls”, Volas means tricks —or, nove

lato means the ace of clubs — or, snore commonly. a stick

¥ esto ez Io certo,

Merern de mis ops,

No" pongst Pleo

(Come with mo, O dack giel of my eyes: even if

you have. no father, you" shall havo a husband

Zod hy cnt 0 gt my dont

complain)

“The morene or dark girl 1s a traditional figure in Spanish folksongs. She

may have Moorish ancestry, and here sho is fatherless. ‘The lest line, No

pong Plesta isa litle cbscure, Usually, plete moans a ivssut or Migation,

bat in this contest i scems to mean singly a complaint

3. Acuérdate, bien mio

London, British Muscum, MS Egerton 9289, ff, 108 vorso-109, the third

sis Voleras’. Heads! "De Ydem': ie, by Sor.

‘and 20° In the last chord the second highest note reads © at bar 6

1A at lar 20 in the original Ether is possible; in the transcription C

has heen adopted.

of

4. Prepirame In tumba

London, British Muscum, MS Egerton 3980, ff. 109 verso-110, the fourth

of ‘Sets Volerae’. Heald “ilo Yen" be, by Sor

[A different anonymous setting for voice and guitar of this poom is in

the same manuscript, (124 verso-125, The words differ lightly, being as

follows

Prenat ne ly wre

aso epi

& Boner asus aoe

BOWS eda

No siento tanto

BL more como el bese

Entre sus brazos

5. Como ha de resolverse

London, British Museum, MS.Eygerton 3289, ff. 110 verso-111, the fifth

‘of “Sele Voloras’. Headed “de Yen's ie, by Soe

6, Muchacha, ¥ ta vereiiensa

London, British Museum, MS Egerton $288, ff 111 versol12,

of Seis Veloras’.

Unlike the other five songs in this sot of six, this one is not epecifically

atebuted to Sor, but it is probable that the attebution was omitted in

for The place of the ual atributicn on the page is taken by the heading

‘La Senta en far, that sy the sath string (or cone) 48 to be tuned to

twill be found, in fact, that the scordatara sn unnecessary. The accom.

niment can readily be played with tho sith string tuned to E.

"A version of this song for two voices and piano is ia London, Clive MS

in the collection of Brian Jolfery. pp. 91-93. tn which the word cucarachas

it roplaced by musaraas (shrews, mice). This version 1 headed “Sogyiilas

ss dup / de Leow, he., by Jou Rodeiguer de Leén.

‘A wealth of popular superstition and symbolism was attached to

cockroaches. For instance, was sspposel that the black beetle, wih which

the cockroach war often Hentifed, ate the core of the apple

1. 21 Voice part frst beat; in the original the eyllable is

writen in each ease st quaver, ‘This has been alterel for the

‘Ske of the acceatuation

16 Voice part, final beat: the original has two quavers, Dutted following

lar 4

15. Voice part, final beat: the omament is Incking in the original, Aled

following bar

1 Si dices que mis ojos

London, British Museum, MS Egeiton 9288, ff, $8 verso-89, The song. is

headed “Valerss de Sere

“All Sor’s are good’, someone has written against this ng in the manu

script. He most have meant not only this one, which is the only. song

ftbuted to Sor in this manuscript but ako those in the twin manuscript

Egerton 3280,

fon schome is not clear in the original. Since the song. is

the repetition scheme of seguidill boleras, as in nos. 1-6,

idopted in the teanscrption, a5 explained tn the elo’ rake

“ve, ‘The final bar is editorial.

Th Cantos Espafoles, ed. E, Oobn (Milaga, 1874), pp. 38-43, is a song,

Alo voice and piano, “Pasi amoroco. wich 4 headed “trust. poe

{Sort y por etros & Munguia. On examination, % ture out to bean

FR Ge Ss gun ais Gel, will tines ‘gato Ufloont stares

“in elaborate piano part, Pethaps Marguia, who was organist of Milaga

Cathedral and a friend of Sors, was responsible for *, or perhaps Ocin ot

pine other acranger,

8, Soguidilias del Requiem eternam: Los canénigos, madre

onion, Clive MS in the collection of Kobert Spencer, pp. 89.91

Sepa il pge with tho wos Seguin del gute earn / Con

“Aconnpto, de Botte Piano / de Sor

‘This was one of Sor's mest populer songs and exists in the following

‘thor versions:

4) A piled veson for two voices and plano, publi London

in 1SL9: a e “

IMPROMTU, / dans To gente dy Bolo, / fait au Sujt di grand

Laruit que on fait / "avec tes Clochos Papeis midi do Ta /

‘Toussaint en Espagne, / Par /F. SOR, 7 Malaga Tan,

180W, as sung by! the / Misses ‘Ashe / Proprdts donne par

Youttur AMF, Ashe. / Ent. Sta. Hall, Price 26/ /- Londen,

ined) by / THE RECENT'S HARMONIC INSTITUTION,

Seven pages, Plate umber 115. Copy: London, Brith Meum,

TWN eo to we alone

No tocarin campanas

oes,

“Muy poco sve

¥ en tal entero

Solon osengese

ita do deel

vont ring belle when 1 die, for the

Seath oft sad person docee't male much nolo.

Belang ina ey mtr Os

oe despa

¥) A printed version for to voices and plano or guitar. The only

known copy, in the Conservatorio di Musica in Mila, lacks title-page, bat

it appears to have formed part of « printed collection of songs, probably

published in Paris. The plate number is $35, and the title BOLERO A

SOCIETE / PAR MA. SOM. The sone ocspes to pages The worts are

Los canbnigos made

Ro teve Mos

(Que Tos que hay en a casa

on seb

Ay madre mio,

A.ch Gananige quire

Paar |

Ne tea coms

Que a muerte de ta tee

‘tur poco suena.

¥ on Las parcequias

EL ieres neal

Mueve fae bolas.

©) A momscript version for solo voice and guitar in the collection of

Robert Spencer, London. Te ocears as 'Boleras / de Sor, one of a numbor

fof songs i a manuscript volume bearing the ttle “Songs / with Accom

ppaniments 7 for the / Spanish Guitar. / 1816, the inseription

and the book-plate of ‘John White Esq’

‘The words ae as follows:

No doblacin campanas

‘Quando yo inuera,

Que la muerte de ui cise

Mui poco suena

‘Two sets of words, then, aro associated with thie melody: "Ne tocarin

‘campanas’ ard “Los eanénigos, madre’. ‘The former ate more appropriate #0

7

& melody based on the Requiem Mass, and te All Saints’ Day, andl so may

well have een the original ones, Of the four sources ouly the’ Clive matin

script certainly dates from Sor's time in Spain, and 0° it ts that version

which Is given im this edition.

The demisemiquavers in bars 1, 3, 19, and 21 are perhaps not to be

taken in strict time,

13. The tie in the piano part & editor

9. EI que quisiera amando

London, Clive MS in the collection of Robert Spencer, pp. 93.95,

Separate title-page with the words ‘Seguiillas / Con Acompto, de'Cruitarma /

Dol Sr. Sots’, ‘original’, and “Revised

4h line 1, the original reads quisler, am older form for quisiera

In line 6, the suelden change from the thitd person to the second seems

to serve to emphasize the signifcance of that lite

30. The oviginal adds a C sharp below the Es in the guitar part

Akered following har 4,

10. Sia otro cuando me quieres

London, Clive MS in the collection of Robert Spencer, pp. 97.99

Separate title-page with the words “Seguidillas / de: Séx

In line 5, mala is short for mala cova

1 Tbe first note ie crowded with no Kes than three vowels: “Si a 0”

Hut the soguidilla form requires a fst ine of seven syllables only, and so

there is no way in which this ean be avoided,

4 and 16 There is no accidental against the F in the piano part in the

‘original The natural & editorial; but it may be that this should be a sharp,

11. Las mujeres y euerdas

London, Clive MS in the collection of Robert Spencer, pp. 109-111,

fe with the words “Segutdila/ Para Guitare / Del SO

‘The repetition scheme is not eloar in the original. ‘The tepetiton scheme

f seguidilar boleas, as in nos. 1-6, las been adopted in the trantenption,

6

as explained in the editorial rote alone. The final bae

original time-sigaature is 3/4,

tn Tine 6, salar means to break, when one is speaking of guitar strings:

bat in connection with people, ie can mean to be initated of estless

3 and 5 In the origina, the underlay in these two bais 4s different

The version of har & has been adopted for the transcription,

35 tn the origina, the A in the voice part is sharp and tke C in the

sitar part x. This has heom altered in the transeriotion

Another anonymoas and totally different setting of this poem, for voice

and gitar, it in London, British Museum, MS Egerton 3980, If. 139 verso

30.

voditoral. The

12. Mis deseuidades ojos

‘The source is a printed edition:

BOLERO DE SQOUETE / avec Accompagnment de Cultare e

a

Piano / COMPOSE ET DEDIE SE. MADAME LA

DUCHESSE DE ROVIGO /PAR M. FERDIN,

ND SOR,

“The song wan pbb in Pare probably carly in 1614, tht is shory

sce Sor ative therefrom Spain ie 1810; by Name Bers as re

fume Cine pubs the fet Hapa elton of hs Sie Petes Pla ae

Jeu a8 bis op. 5) ane tino patron sone by ine tes Ine

Lblogrephe do TEnpie Fretran on 4 Febery Told. The oa feat

«ony, sind by Sor, fn the BibltNeque Naso, Pai

The delist, the Duches of Rovigh vas the wile of Anne ean Mari

ent Swvmry, Due de Rovio, Frowh soldier and contdant ef Nope,

Tho song i exception ht tn tm Wat K camer om 6 Pee

euro, that ‘tht source dates rom after Sor's departure fom Spin hee a

ts ‘original altermative accompeniments for guar or fo" panes ant th

Cutt mere than one sara. Silly, phage should aor'he Seta

hu fe boon inched, Rly beciute probably was compen wie

Spe wat atl in Spain, ae secon onder to compte The cht

al So" Koon bolero: and guile wih guar tal he Ir ne ae

wh plano

12 The origin undety does not sido me and ei. This gives one

slble ta many forthe ne and hs heen change) accel

35 uit: pat: in the exgal thve 4 a slur tom the of the fst

leat to the Gof the second be

17 In the hast goup of seniguavers, the Bs are presumably Ht, both

becaue of the B Ri in de accomprnatent and on the analy of har

wee the Mati specited Hat Ht not lear whether the fe veo We

Sar shut bo fat‘ naturel Inthe transciponi has been sme to he

natural on the analogy of bue 4 whe the fat Is specibal

21 The gaia and piano pats (bat not the sce) have & queer Sted

of crotehe in the eral "

7

CESA DE ATORMENTARME

Gesa de atormentarme,

Cruel Memoria,

Acordindome un tiempo

Que fui dichoso,

Y atin Io seria

Si olvidarme pudiera

De aquellas dichas.

(Cease tormenting me, cruel Memory, re-

minding me of a time when 1 was happy.

Happy wouki I be still, if 1 could but

forget that happiness.)

In all adversity of fortune the, most

wretched is once to have been happy.’ Thus

Beethius (De Consolatione Philosephiae, 11

i), and the theme was very much in vogue

in Spanish Renaissance poetry and there-

ajter in traditional love. poetry. Memory

here torments the poet with recollections

of past happiness. The personification of

Memory is a technique characteristic of ear

lier tove poetry

Bes aie 5 mes tae fa, A-cor- din- do- me un

Siol-vi-dar- me pu-

Que fut die A cor- din- do- me un

Dea-que- las Siol- vi- dar- me pu-

Que fui di-

Dea-que- les

2

DE AMOR EN LAS PRISIONES

De amor en las prisiones

Gozosa vivo — jay!

Y sus dulees cadenas

Beso y bendigo — jay!

Y ol verme libre

Mis que el morir me fuera

Duro y sensible — jay!

(Happy I live in Love's prisons, and 1 kiss

tnd Pies its sweet chine "And to, Bid

iyself free would bo harder and more

ful for me than death.)

GUITAR

A woman's song. as the word gozosa shous.

This was rightly one of the most popular

of Sor's songs: see the notes for details of

other versions.

- 2 sve Yo sus dul- ces

Ye ver-me ik = 5+ = -bre Mis que el mo- rir me

———____. ————— - i

at = = Sate

6 SS SS Sr es

ra Du- ro ysen- i - = = = ble, Mis que el mo-rir me fue = = = =

fe SS

yp?

ae Be- so yben-di- go

ra Du- 10 ysen- si- ble.

6 ~ ze o = = =

a i a +e"

2 7

23

3

ACUERDATE, BIEN M[O

Aenérdate, bien mio,

Cuando solias

Buscar las ocasiones

Para las dichas.

Y ahora mudable

Huyes atin de las mismas

Casualidades.

(Remember, my dear, how you used to look

for opportunities for happiness. And now,

fickle, ‘you flee from just such opportu:

nities.)

The opportunities for happiness which the

poet has in mind are, doubtless, oppor

tunities for amorous encounters.

Andante _

: E == eer See eee

7 SS =

Feur- da- te, bien mf 4

GUITAR,

4

Cuan do Bus- car las o-

Y aho-ra Hu- yes atin de

jus -car las o-

Hu- yes aun de

fie a ome Pa- ra as di - - - ~chas.

mas Casa-He da- == = + + des, Ca-sua- is das = ~des.

Prepirame a tumba,

Que voy a expitar

Fn manos de ky madre

De la falsedad.

No siento tanto

1} morir como hallarme

En tales brazos.

for 1 shall die

of all falschood.

to find myself in

(Prepate for me my tor

the agms of the moth

th L fear less. tha

sich arms)

Andante

4

PREPARAME LA TUMBA

Death in this poem is probably to be taken

in an amorous rather than i 4 literal sense.

‘The mother of all falschood’ is a strong

expression; yet the lover is still in her arms.

—— phere ges

GUITAR

oJ

me En tar les

re De la fal

é P = ips

@é Zs

wu

aS

re De In fal- s6-

me En ta-les bra

——

pt

aL

7

GUITAR

=

COMO HA DE RESOLVERSE

No doubt the ship of passion and the sea

fof love are meant, No estribillo is gévon; if

there ever was one, perhaps it developed

this image.

Para 86

Aquel que desde lejos

Ve tempestades?

(How can he resolve to set sail who sees

tempests approaching from afar?)

Andante

Pos mem- bar- ears = - 2 = - =

z

a =

f =e

h :

" 6-8 fe Sa

- ww

6

MUCHACHA, Y LA VERGUENZA

Muchacha, y la vergiienza, Tooth-marks, it seems, have aroused the

{Dénde se ha ido? ‘mother’s suspicions regarding her daugh-

“Las cucarachas, madre, ter's honour. But what exactly is meant by

Se Ta han comido” the cockroaches?

Muchacha, mientes,

~ Hussy, you're

lying: cockroaches don't have teeth.)

Andante

gDin- dese ha

GUITAR

o>

Dén -de se ha i+ + do? ‘Las

Mu -cha~ cha, = = + = tes, Por

la han co- —mi- ~~ do, Las cu-ca- ra- chas, mad- re, Se la han wo

No tie- men dien = : - Por-que ls ets cas me No ties nen

Si dices que mis ojos

Te dan la muerte,

Confiésate y comulga,

ue voy a verte,

Porque yo creo

Me suceda lo

Sino te veo.

(If you say that my eyes Kill you, then

make confession; take the sacrament; for

Tm going to see you. For 1 believe that

the same thing will happen to me unless

L see you)

[Andante]

7

SI DICES QUE MIS OJOS

Awoniew’s song. The so guice_ of

seeen line, the pom gives @ teat it to

Se Moves then kee anced Ue

Teel Enon liché about dying. of. 1000:

the porer of hits lady's eyes has bewitched

hi! 99 tt only “deuth-—embicalntiy,

either in the literal or sexual sense —can

fellove hin. For hor, lovceoen, iis the

‘other xy found: nol to sce her lover te

Macth for hen The avo of reigns erm

nology tn lows poolg ta omclon, ane cher

cleric of the worly Spanish: Rewaisscace

canons

= oa

di- ces que mis o- = = jos Te dan la

GurraR|

mis In

To dan la mace - = = = T= te, Con-fié. sas teyo- ml. . == SS a Que voy a

Porque yo oe-- =~ Deo) Me su-ce-da lo miss 2-22 eee mo Si- no te

mul = = ga, Que voy a

mis-- -mo Si- no te ve- 0

Fi) TF

Fo-yi =

sa- te y co- mul- ga, Que voy a ver

ce- da lo mis- mo $i- no te ve

~

8

SEGUIDILLAS DEL REQUIEM ETERNAM

Los canénigos, madre,

(Canons, mother, don't have children; those

that they have in their house are little

nephews and nieces. Oh, mother, T want a

‘Son sobrinitos. canon, s0 that I can be an aunt!)

‘Ay, madre mia,

Un canénigo quiero This Iumorous anti-clerical song. parodies

the ‘intonation of a requiem mass.

Andante

ae =) 2 Peja eee]

3 a ina = ¥ See

Los ca-né -ni-gosymad -re, No tie-nen hi- fos; Los que tie-nen en ca- sa Son sob-ri- ni- tos. Los

ca- nd- nt- gos,

| eS |

we

PIANO

que tie-nenen ca-sa Son soberie nhs = = 2 tos,

g

EL QUE QUISIERA AMANDO

E] que quisiora amando

Vivir sin. pena,

Ha de tomar el tiempo

Conforme venga.

Quiers querido;

Y $i te aborrecieren

Haga lo mismo.

(Fle who wants to Jove and yet live

svithout problems, must just take time as it

comes, Take someone to love; and then,

even if they hate you for it — just take time

as ite

Andante

= = —————— = SS ES ae f=

BL que quis sie- mw a

curr aR l@y > aS SSS a es Sl ow == AS =

: == =

é 3 o —e =

10

SIA OTRO CUANDO ME QUIERES

Sis to euidy me quiere {Hf you givo your hand to someone eso

| mano le das, even when you love me, just think wha

Guando ya no me quieras, you'll give him, when you've stopped lovin

TDi qué le daria Beal Te wenldet bo a bad thing’ 1 died

Joving such a bitch)

No fuera mala .

E] que yo me muriera A man is addressing a woman, as the word

Por umm canalla otro shoves, And in the last three lines it

seems that even knowing her ficklencss, he

Andantino cant stop loving her

Siaot-ro cuando me quie- ~~ a m-no le

PIANO

das, ds, Cuando ya no me

aL que yo ime

38

—

Cutan-do me quie

i qué le

toe EL que mu = rie

Por un ca

Di qué Te qué Ie

Por um ca- meas na

i

LAS MUJERES Y CUERDAS

Las mujeres y cuerdas

De Ia guitarra,

Es menester talento

Para templarlas.

Flojas_ no suenan,

Y suelen saltar muchas

Si las aprietan,

(Women and guitar strings: you need

falene to tune them Ir theyre Mack they

don't sound; and lots of them, if you

tighten them too much, break.)

Allegro poco

Las mu- je-resy cuer= das,

GUITAR

De la gui- tar

An ainusing song, to a poem widely current

in ts day. in which the guitar aceompan

ment provides a firm reinforcement for the

flowing rhythm,

—

Tas mu =je-tes y

gui

De Ia gui-

Flo- jas no

to Pa-ra tem- prs. - ~~

has, Y sue-len sal-tar mu-- ~~ - = = -chas Pa a

Pa-m tem- plar- - +--+ - las, Es me- nes-ter ta- Ten - to, i me- nes-ter ta-

las y sie~ Ten sal-tar ma = chas, sue- Ten sal-tar

= to Pa-ratem= plar- fas, Pa-ra tem- plar

chas Silas ap -rie~ tan, Si Iasap> tie

Mis desenidados ojos

Vieron tu cara.

10h qué cara me ha sido

Esa miradal

Me cautivaste,

Y encontrar no he podido

Quien me rescate,

Ya tomardn mis ojos

‘A buen partido,

Para. no. verte siempre,

No haberte visto

Pues tienes cosas

Que slo debe verlas

EL que las goza.

De mi parte a tus ojos

Dies que callen,

Porque si les respondo

Quieren matarme,

Y es fuerte cosa

Que ha de callar un hombre

Si le provocan.

a

nr

MIS DESCUIDADOS OJOS

(My careless eyes saw your face. Ob, how

dear that sight cost_me! You captivated

‘me, and [ have found no one to rescue me

My eves will now resolve never to have

‘seen you, in order that they may not be

Obliged to see you eternally, Por you

fess things wiih should be seen only

¥y him who enjoys them.

Tell your eyes, on my behalf, to be silent;

for if T reply, they seck to kill me. And it is

Heed for be silent if they provoke

him,

This love poem begins with a play on cara

Cjace’) and cara. (costly). The word ojos

appears at the heginning of each stanza,

‘and the whole poem plays on the amorous

innugery associated with eyes: the sight of

the beloved cost the Tover dear: his eyes

try to forget that they, ever saw hers the

lady's eyes try to slay him, and he asks her

to prevent them jrom doing 90.

Andantino

Mis dex -eui- da- dos

curraR

PIANO

{alternative to guitar)

8

ro a 2

Vie- ron twee

Vern ge 3 63H Sues = « Oh qué ct ame ha

- 2 iin 3 ned 8 aed Yen-con= ar no he po-

E- sa mie

Quien meres

Se

9

ep

Oh qué ca- mame bn

Yen-oon- tar 10 he p=

\

=F

45

FACSIMILES

wi

Dene

<

——S

Sie oil

#

ces --

LU « legyev.

yr

Hts

que el wiergy HES

Ze 5 ta

Pf SEULLOS

PU AALIUE

VL hl

' TF

af

egurdillaf

ara ., C®

YO on Arorye.” de itrarnn.

vv

Voor a.” Sort y

yo

Vt

femaPey

ca

= == ———

pane aE S==

=a SSE

a7 que gui Jie yea man ~~ ~~ ~ Fg = > vir vizpe —

ee ————

o F = GF ¥e

— j= 5 SSS A= 255

na vt vir J) PE-~ ~ -> Aa er =e

pale em a

aw

LE BOLERO.

LH SOLERO, |

bstantivement pour dsigner

tune danse espagnole, toujours appelée Sagudla done

laquelle un danseur, nommé olor, introduisit des pss

«gui exigdront queljues modieations dans e mouvement

cele rhythme daccompagnement de Fair pr

porlant de Uair ainsi modifié, on Tappelait Segnédtn |

Bolera et en parlant de la danse, ef baile Bolero (la

danse Bolériennw) , et You Bnit par diee simplement ef

Bolero. On a eependant consersé un souvenir de son

origine, puisqac, dans les contrdles des troupes de theitre

cx Espagne , celui qui exdoute cette danse est appelé ef |

Bolero jon nome aussi la danseuse a Bolera, par la

seule raison qu'elle est sa compagne. Crest ainsi qu'on |

it en frangsis des Dugazon, les Posie, quand on parle

dia Hide cee pari ces atieura, |

Ge qui constitue le Bolero, cest Yair scul et non le|

hythe daccompagnement. Ce rhythme peut varier

sans que fe Bolero perde son caractive distinetif, et on

fon sert encore pour accompagner une polonaise on

plusieurs pidees d'un genre diftérent

Cot air est fondé sur le métre et Taccentuat

vers qui forment le couplet et MBurivillo, dont Ven

semble est appelé Segudlla, Le couplet est composé

de quatre vers; Ie premier ct le troisitme sont de sept

aqllabes, et les deus autres de cing, L'Bstrvdio ost com

poséide trois vers, qui répondent, quant & Ja quanti

de syllshes, aus second, (oisiéme et quatribme vers da

couplet, La rime est do Hgueur entre Je second tb |

4 du couplet, et entre Te premier ot ke

tiisirme de Purvis es autres vers peuvent ne pas

me peut tre consonante ou assonantc

Zr BOLERO. a

assonnant

wwe identité du voyeles d

es de chayue vers. quoiqa

rents. Lit rime consonn:

al

a plusiours manicres de mettre dus Seguiditlas en

excepHe trois (Saguidillas serins,

st celle qui consti

Is deus dernitnes | au Tiew d@ow sur Pavantderniére, dans le second et le

quatriéane vers du couplet, ainsi que sur le premier et le

troisiéme de I Estrivillo , mais jamais dans les utes,

Lexemple UF indique Teneadvement des pi

sort do formule A tous les Bolerns, c'est-a-dine a In Se-

_gnidilla Bolero

res Segnidillas qui ser

les conson

qui les

te cat

oles, qi

mnt 8 faire danser

Je-eow;alors| appa pourenit se trouver sur a dernigre-ssiibe

}

rililas de teatro y Seguidlfas do sociedad’, soot ¢

nesure a trois temps, ot se troavent renfermées dans | Furent les Mnchegazs, cause le leur mouvement plus

c enchissennent musical; le degeé de Jentewr ou | vite quc eelui des Marcians, t surtout des Sorldanas ¢

de vitesse dans le mouvement ct la difference d t V0 presque tou » note par syllabe,

rhythine daecompagnement,désignent les nuanees entre | excepts eur Vavant-dernién tla durée de la

Seguitillas Manchegas, Murcianas, Sevillanas, Boleras, quelle on fait quelyu ion (exomple ID), La gui=

del Kojo, quo Von finit par appeler Reyugjo, et ane tare maryue le temps Fort et faible de fam

en eroches, en commencant avee le pouce La note ind

quée, plus basse que los autres; Findex ot Ie med

cen remontant, passe avee rapidité sur lee des ou

re deus, trois on quatre | condes infiriewres et produit la seconde erochos Ia»

temps en ame eroche etdeus doubles eroches et le veste | chute de La main, sons éearter les doigts, produit la

de In mesure en eroches. Del partie forte du second temps, Finds wédins la

de le nnit, qui ne ressemble pas plas an earactére de | portic faible; et le mime proc 1 jusqu'an second

| musique éspaguote que te mode wiincur, et surtout Ie} temps de ta seconde mesures que Ton Frappe ayce le

tan chant d'ailleurs trés joli du| pouee, en faisant de suite Tautre eroche avec Tindex

netire Geossais, On voit souvent |en remontant; an fait Je dernier temps de méme que |

le second et Fe woisiéme de Ta prem

| doigts de la main droite restent toujours dans Ia meme

ps, et dont Le com est préeéde par | position, Ie pouce et Findex un pew ceartés

(s du pretenda aliythaie d'accompagnement | Toutre, Le méatius touchant Findex, et los deus eutros

rv natinell «a

du premier temps d'une i

| seconle minewre da

air, n'a le ca

n met ¢

ua de

deus,

que Tautear conlond arce le Zolere. On éviterait cos) dane leur posit w diattaquer lea corde

méprises en faisant des recherehos qui n’exigeraient | dépend on du poignet, Le nombre de

qu'un peu dobservation ot de prtionee. fois que li guitare répéte les deus premicres mesures

Pour bien saisir la coupe de Fair, il faut se introduction n'est point &; mais une fois le

He des paroles ainsi que de leur thythme. Je désive yonee il doit continuer ainsi, On pourrait, si

seulement foire sentir en Francais Pellet dun couplet de a danser, prolonger Ie rhythme

Seguitdlda. Caccompagnement, pouirvin que le chemtewr attende,

de

coveare csriewe pour continuer, la quatritme eroche d'une seconde me-

Nie die ulnar | sure.

as eae quieres pas du Bolero est compose ile six temps, qui com

Mira que te mencent & compter sure second temps de La einguieme

i P r i

sy me is rmosnne, of fnissent au cinguiéme temps de Ia teoisieme,

qui ost le pren

pas de Segwidiléa emploie d

‘exemple il). Le pas se fat ain

position , le pied de devant marque le premier’ temps de

danse; en baissa ‘ome

position, on manque le second temps en faisant jouer un |

oops d'une anter, ce qui Fait qu’an

Sita vewe wie rejoin,

v

Se sera ss Le muasqu

‘Tes Folie

Cluonehe Mais

(ui porte wae personel,

Ta Nene elise

Ia pointe et en premant In quat

1 Te geno, comme si Ton voulait faire un rond de

xe, 61 toijours av eela pointe baissée, om porte le pied

ila deusigme position ; Ie troisiéme temps se manque en |

portent le pied qui a manquéles deux premiers temps tout:

we,

Formate de Segatillla

Br beoo7, le lg bo oer(r cet

St ter veux me re you dire viens ine the a-

a

l-b-Wrete co belie op oer ite ad BI

Pen oe tm nome in sn

meer 2.8 Sse SS

Soe eee Se

IP Loe ocreolelo ete rl

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Dokumen - Tips - Partitura La VioleteraDocument6 pagesDokumen - Tips - Partitura La VioleteraLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- 2022 - 10 - 10 - Programacao Externa Outubro Com Sinopses - Teatro AmazonasDocument15 pages2022 - 10 - 10 - Programacao Externa Outubro Com Sinopses - Teatro AmazonasLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- La Direction D'orchestre: Table Des MatièresDocument4 pagesLa Direction D'orchestre: Table Des MatièresLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- El Cant Dels Ocells, CelloDocument1 pageEl Cant Dels Ocells, CelloLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Nava Op39Document7 pagesNava Op39Lionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Nava 6itarian AriettsDocument7 pagesNava 6itarian AriettsLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Porro Op04Document31 pagesPorro Op04Lionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Fernando Sor Seguidillas PRDocument59 pagesFernando Sor Seguidillas PRLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Moretti F-La InsinuacionDocument2 pagesMoretti F-La InsinuacionLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Damas T-La HechiceraDocument4 pagesDamas T-La HechiceraLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Damas T-Asi Son TodosDocument4 pagesDamas T-Asi Son TodosLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Damas T-Fandango y CoplasDocument4 pagesDamas T-Fandango y CoplasLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- PEC Actualiz 21 - 22Document36 pagesPEC Actualiz 21 - 22Lionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Damas T-Dulce MemoriaDocument4 pagesDamas T-Dulce MemoriaLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Castro Journal Espagnol 13Document3 pagesCastro Journal Espagnol 13Lionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- India BellaDocument1 pageIndia BellaLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Agrupaciones de Lengua y Cultura Españolas en Francia: Currículo AlceDocument2 pagesAgrupaciones de Lengua y Cultura Españolas en Francia: Currículo AlceLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet

- Audicià N Departamental de La Asignatra de Guitarra Viernes 20 de Mayo 2022 17 - 00 H. Salà N de Actos de San Estebã¡nDocument2 pagesAudicià N Departamental de La Asignatra de Guitarra Viernes 20 de Mayo 2022 17 - 00 H. Salà N de Actos de San Estebã¡nLionel Andrés MessiNo ratings yet