Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ACOG Committee Opinion No 757 Screening For.42 PDF

ACOG Committee Opinion No 757 Screening For.42 PDF

Uploaded by

Diana Mendoza0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pagesOriginal Title

ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__757__Screening_for.42.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pagesACOG Committee Opinion No 757 Screening For.42 PDF

ACOG Committee Opinion No 757 Screening For.42 PDF

Uploaded by

Diana MendozaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

INTERIM UPDATE

ACOG COMMITTEE OPINION

Number 757 (Replaces Committee Opinion No. 630, May 2015)

Committee on Obstetric Practice

This Committee Opinion was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice.

INTERIM UPDATE: This Committee Opinion is updated as highlighted to reflect a limited, focused change in the

language and supporting evidence regarding prevalence, benefits of screening, and screening tools.

Screening for Perinatal Depression

ABSTRACT: Perinatal depression, which includes major and minor depressive episodes that occur during

pregnancy or in the first 12 months after delivery, is one of the most common medical complications during

pregnancy and the postpartum period, affecting one in seven women. It is important to identify pregnant and

postpartum women with depression because untreated perinatal depression and other mood disorders can have

devastating effects. Several screening instruments have been validated for use during pregnancy and the

postpartum period. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that obstetrician–

gynecologists and other obstetric care providers screen patients at least once during the perinatal period for

depression and anxiety symptoms using a standardized, validated tool. It is recommended that all obstetrician–

gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being

(including screening for postpartum depression and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive

postpartum visit for each patient. If a patient is screened for depression and anxiety during pregnancy, additional

screening should then occur during the comprehensive postpartum visit. There is evidence that screening alone

can have clinical benefits, although initiation of treatment or referral to mental health care providers offers

maximum benefit. Therefore, clinical staff in obstetrics and gynecology practices should be prepared to initiate

medical therapy, refer patients to appropriate behavioral health resources when indicated, or both.

Recommendations and Conclusions during pregnancy, additional screening should then

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecolo- occur during the comprehensive postpartum visit.

gists (the College) makes the following recommendations c Women with current depression or anxiety, a his-

and conclusions: tory of perinatal mood disorders, risk factors for

c The American College of Obstetricians and Gyne- perinatal mood disorders, or suicidal thoughts

cologists (the College) recommends that warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation,

obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care and assessment.

providers screen patients at least once during the

c There is evidence that screening alone can have clinical

perinatal period for depression and anxiety symp-

benefits, although initiation of treatment or referral to

toms using a standardized, validated tool. It is rec-

mental health care providers offers maximum benefit.

ommended that all obstetrician–gynecologists and

other obstetric care providers complete a full Therefore, clinical staff in obstetrics and gynecology

assessment of mood and emotional well-being practices should be prepared to initiate medical ther-

(including screening for postpartum depression apy, refer patients to appropriate behavioral health

and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the resources when indicated, or both.

comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient. If c Systems should be in place to ensure follow-up for

a patient is screened for depression and anxiety diagnosis and treatment.

e208 VOL. 132, NO. 5, NOVEMBER 2018 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Introduction Anxiety is a prominent feature of perinatal mood

The prevalence of perinatal depression is a significant disorders, as is insomnia. It may be helpful to ask a woman

cost to individuals, children, families, and the commu- whether she is having intrusive or frightening thoughts or is

nity. In 2011, 9% of pregnant women and 10% of post- unable to sleep even when her infant is sleeping. Women

partum women met the criteria for major depressive with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal

disorders (1). It is important to identify pregnant and mood disorders, risk factors for perinatal mood disorders

postpartum women with depression because untreated (Box 1), or suicidal thoughts warrant particularly close mon-

perinatal depression and other mood disorders can have itoring, evaluation, and assessment. These women may ben-

devastating effects. Regular contact with the health care efit from evidence-based psychologic and psychosocial

delivery system during the perinatal period should pro- interventions and, in some cases, pharmacologic therapy

vide an ideal circumstance for women with depression to to reduce the incidence and burden of perinatal depression

be identified and treated. The College recommends that (9). If there is concern that the patient suffers from mania or

bipolar disorder, she should be referred to a psychiatrist

obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care pro-

viders screen patients at least once during the perinatal before initiating medical therapy because antidepressant

period for depression and anxiety symptoms using monotherapy may trigger mania or psychosis (10). Mania

symptoms include inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, feeling

a standardized, validated tool. It is recommended that

all obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care pro- rested after only 3 hours of sleep, or engaging in risky

viders complete a full assessment of mood and emotional behaviors that worry her friends and family (5).

well-being (including screening for postpartum

depression and anxiety with a validated instrument)

during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each Box 1. Risk Factors for Perinatal

patient (2). If a patient is screened for depression and Depression

anxiety during pregnancy, additional screening should

then occur during the comprehensive postpartum visit. Depression during pregnancy:

When indicated, obstetrician–gynecologists and other Maternal anxiety

obstetric care providers share a role in initiating medical Life stress

therapy or referring patients to appropriate behavioral History of depression

health resources, or both.

Lack of social support

Depression, the most common mood disorder in the

general population, is approximately twice as common in Unintended pregnancy

women as in men, with its initial onset peaking during Medicaid insurance

the reproductive-age years (3). Therefore, it is not sur- Domestic violence

prising that perinatal depression, which includes major Lower income

and minor depressive episodes that occur during preg- Lower education

nancy or in the first 12 months after delivery, is one of

Smoking

the most common medical complications during preg-

nancy and the postpartum period, affecting one in seven Single status

women (4). Perinatal depression and other mood disor- Poor relationship quality

ders, such as bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders (5), Postpartum depression:

can have devastating effects on women, infants, and fam- Depression during pregnancy

ilies; maternal suicide exceeds hemorrhage and hyperten-

Anxiety during pregnancy

sive disorders as a cause of maternal mortality (6).

Perinatal depression often goes unrecognized because Experiencing stressful life events during pregnancy or

changes in sleep, appetite, and libido may be attributed to the early postpartum period

normal pregnancy and postpartum changes. In addition to Traumatic birth experience

health care providers not recognizing such symptoms, Preterm birth/infant admission to neonatal intensive care

women may be reluctant to report changes in their mood. Low levels of social support

In one small study, less than 20% of women in whom Previous history of depression

postpartum depression was diagnosed had reported their

Breastfeeding problems

symptoms to a health care provider (7). Therefore, it is

important for obstetrician–gynecologists and other

Data from Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM,

obstetric care providers to ask the pregnant or postpartum Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during preg-

patient about her mood. Newborn care appointments also nancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:5–14

may be an opportunity to ask a mother about her mood. and Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal

Obstetric providers should collaborate with their pediatric risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent

colleagues to facilitate treatment for women with mood literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:289–95.

disorders identified during newborn care (8).

VOL. 132, NO. 5, NOVEMBER 2018 Committee Opinion Perinatal Depression e209

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

In 2016, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force a mental health specialist and a primary care provider.

changed its recommendation for routine depression Systems should be in place to ensure follow-up for diag-

screening to a B, endorsing depression screening in the nosis and treatment (9, 10).

general adult population, including pregnant and post-

partum women (11). Although there are no large ran- Screening Tools

domized controlled trials that definitively prove the Several screening instruments have been validated for

benefits of screening alone without the necessary treat- use during pregnancy and the postpartum period to

ment, the task force changed its recommendation based assist with systematically identifying patients with peri-

on a large systematic review. This review combined six natal depression (Table 1). The Edinburgh Postnatal

randomized controlled trials that screened pregnant or Depression Scale (EPDS) is most frequently used in the

postpartum patients with or without additional care research setting and clinical practice for several reasons.

offered based on results of screening. Most of the trials The scale, which has been translated into 50 different

provided some type of treatment or support beyond languages, consists of 10 self-reported questions that

screening, such as counseling, treatment protocols, or are health literacy appropriate and take less than 5 mi-

training to clinicians and ancillary staff. Thus, it is diffi- nutes to complete. The EPDS includes anxiety symp-

cult to distinguish the effect solely due to screening or toms, which are a prominent feature of perinatal mood

screening combined with some type of intervention. disorders, but excludes constitutional symptoms of

Nevertheless, follow-up of these patients several weeks depression, such as changes in sleeping patterns, which

to months later demonstrated an absolute risk reduction can be common in pregnancy and the postpartum

in depression prevalence of as much as 9% (12). Greater period. The inclusion of these constitutional symptoms

benefits were seen if clinical support and training were in other screening instruments, such as the Patient

offered to the staff that provided the screening tool. Health Questionnaire 9, the Beck Depression Inventory,

Initiation of treatment or referral to mental health and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression

care providers offers maximum benefit. Clinical staff in Scale (Table 1), reduces their specificity for perinatal

obstetrics and gynecology practices should be prepared depression. In addition, with the exception of the

to initiate medical therapy, refer patients to appropriate Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and the EPDS, other

behavioral health resources when indicated, or both. instruments have at least 20 questions and, thus, require

Recent evidence suggests that collaborative care models more time to complete and to score. As with any

implemented in obstetrics and gynecology offices screening test, results should be interpreted within the

improve long-term patient outcomes (13). For example, clinical context. A normal score for a tearful patient

in one model of collaborative care, a depression care with a flat affect does not exclude depression; an ele-

manager, such as a nurse or social worker, can provide vated score in the context of an acute stressful event

psychotherapy and support under the supervision of may resolve with close follow-up.

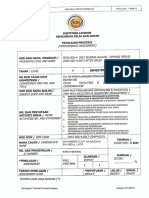

Table 1. Depression Screening Tools

Number of Time to Complete Sensitivity and Spanish

Screening Tool Items (Minutes) Specificity Available

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 10 Less than 5 Sensitivity 59–100% Yes

Specificity 49–100%

Postpartum Depression Screening 35 5–10 Sensitivity 91–94% Yes

Scale Specificity 72–98%

Patient Health Questionnaire 9 9 Less than 5 Sensitivity 75% Yes

Specificity 90%

Beck Depression Inventory 21 5–10 Sensitivity 47.6–82% Yes

Specificity 85.9–89%

Beck Depression Inventory-II 21 5–10 Sensitivity 56–57% Yes

Specificity 97–100%

Center for Epidemiologic Studies 20 5–10 Sensitivity 60% Yes

Depression Scale Specificity 92%

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale 20 5–10 Sensitivity 45–89% No

Specificity 77–88%

e210 Committee Opinion Perinatal Depression OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Conclusion 6. Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ.

Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings

Perinatal depression is a common complication of from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet

pregnancy with potentially devastating consequences if Gynecol 2011;118:1056–63.

it goes unrecognized and untreated. There is evidence

that screening alone can have clinical benefits, although 7. Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L. The pathway to care in

initiation of treatment or referral to mental health care post-natal depression: women’s attitudes to post-natal

providers offers maximum benefit. Systems should be in depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:

427–8.

place to ensure follow-up for diagnosis and treatment.

Therefore, the College recommends that obstetrician– 8. Earls MF. Incorporating recognition and management of

gynecologists and other obstetric care providers screen perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric prac-

patients at least once during the perinatal period for tice. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and

depression and anxiety symptoms using a standardized, Family HealthAmerican Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics

validated tool. It is recommended that all obstetrician– 2010;126:1032–9.

gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete 9. Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiol-

a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being ogy, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and

(including screening for postpartum depression and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:961–77.

anxiety with a validated instrument) during the

comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient. If 10. Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell

DL, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression dur-

a patient is screened for depression and anxiety during ing pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric

pregnancy, additional screening should then occur Association and the American College of Obstetricians

during the comprehensive postpartum visit. and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:703–13.

For More Information 11. Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC,

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. Screening for depression in

has identified additional resources on topics related to this adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommenda-

document that may be helpful for ob–gyns, other health tion Statement. US Preventive Services Task Force

(USPSTF). JAMA 2016;315:380–7.

care providers, and patients. You may view these resources

at www.acog.org/More-Info/PerinatalDepression. 12. O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Bur-

These resources are for information only and are not da BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depres-

meant to be comprehensive. Referral to these resources sion in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report

does not imply the American College of Obstetricians and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task

and Gynecologists’ endorsement of the organization, Force. JAMA 2016;315:388–406.

the organization’s website, or the content of the resource. 13. Melville JL, Reed SD, Russo J, Croicu CA, Ludman E, LaR-

The resources may change without notice. occo-Cockburn A, et al. Improving care for depression in

obstetrics and gynecology: a randomized controlled trial.

References Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1237–46.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PRAMStat System.

Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/work- Published online on October 24, 2018.

directly-PRAMS-data.html. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

Copyright 2018 by the American College of Obstetricians and

2. Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG Committee Opinion Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may

No. 736. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecol- be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

ogists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written

3. Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in women: implica- permission from the publisher.

tions for health care research. Science 1995;269:799–801. Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be directed to

Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA

4. Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner 01923, (978) 750-8400.

G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1071–83.

409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statisti- Screening for perinatal depression. ACOG Committee Opinion No.

cal manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): 757. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet

APA; 2013. Gynecol 2018;132:e208–12.

VOL. 132, NO. 5, NOVEMBER 2018 Committee Opinion Perinatal Depression e211

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

This information is designed as an educational resource to aid clinicians in providing obstetric and gynecologic care, and use of this information is

voluntary. This information should not be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. It

is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating clinician. Variations in practice may be warranted when, in the

reasonable judgment of the treating clinician, such course of action is indicated by the condition of the patient, limitations of available resources, or

advances in knowledge or technology. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reviews its publications regularly; however, its

publications may not reflect the most recent evidence. Any updates to this document can be found on www.acog.org or by calling the ACOG

Resource Center.

While ACOG makes every effort to present accurate and reliable information, this publication is provided “as is” without any warranty of accuracy,

reliability, or otherwise, either express or implied. ACOG does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse the products or services of any firm, organization, or

person. Neither ACOG nor its officers, directors, members, employees, or agents will be liable for any loss, damage, or claim with respect to any liabilities,

including direct, special, indirect, or consequential damages, incurred in connection with this publication or reliance on the information presented.

All ACOG committee members and authors have submitted a conflict of interest disclosure statement related to this published product. Any potential

conflicts have been considered and managed in accordance with ACOG’s Conflict of Interest Disclosure Policy. The ACOG policies can be found on acog.

org. For products jointly developed with other organizations, conflict of interest disclosures by representatives of the other organizations are addressed by

those organizations. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the

development of the content of this published product.

e212 Committee Opinion Perinatal Depression OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Psychotropic Medications During PregnancyDocument20 pagesPsychotropic Medications During PregnancyMaria Von ShaftNo ratings yet

- Screening Tools For PostpartumDocument9 pagesScreening Tools For PostpartumNeni RochmayatiNo ratings yet

- RP Pattern Patsy Party Dress Ladies US Letter PDFDocument99 pagesRP Pattern Patsy Party Dress Ladies US Letter PDFЕкатерина Ростова100% (5)

- Postpartum PsychosisDocument25 pagesPostpartum PsychosisWinset Bimbitz JacotNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Depression: Clinical PracticeDocument11 pagesPostpartum Depression: Clinical PracticeCasey Daisiu100% (1)

- Velez - Trade For WealthDocument91 pagesVelez - Trade For Wealthwappler99100% (14)

- Management of Postpartum DepressionDocument12 pagesManagement of Postpartum DepressionAnnisa Chaerani BurhanuddinNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Medication Use in Pregnancy and BreastfeedingDocument19 pagesPsychiatric Medication Use in Pregnancy and BreastfeedingYamiletRomeroVillaNo ratings yet

- Bollard Design Rev 2Document5 pagesBollard Design Rev 2Sameera JayaratneNo ratings yet

- The Oil and Gas Engineering GuideDocument8 pagesThe Oil and Gas Engineering GuideRiad Alsaleh67% (3)

- ONLINE JEWELLERY SHOPPING FinalDocument58 pagesONLINE JEWELLERY SHOPPING Finalkapoorggautam9078% (58)

- MJDF Part 1 OCTOBER 2019Document7 pagesMJDF Part 1 OCTOBER 2019sajna1980No ratings yet

- Volkswagen Golf: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument23 pagesVolkswagen Golf: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchKhaled FatnassiNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Depression Among Saudi Pregnant WomenDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Depression Among Saudi Pregnant WomenIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Treatment and Management of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum ACOG June 2023Document27 pagesTreatment and Management of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum ACOG June 2023kaiorm2k100% (3)

- Depresia Postpartum PDFDocument25 pagesDepresia Postpartum PDFAndreea Tararache100% (1)

- Committee Opinion: Screening For Perinatal DepressionDocument4 pagesCommittee Opinion: Screening For Perinatal Depressionjanicesusanto2000No ratings yet

- Mental Health in PregnancyDocument9 pagesMental Health in PregnancypunchyNo ratings yet

- Postnatal Depression Shakespeare BMJ - 2014Document3 pagesPostnatal Depression Shakespeare BMJ - 2014Tebah AlatwanNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Perinatal DepressionDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Perinatal Depressionc5rf85jq100% (1)

- Mekanisme Post PartumDocument20 pagesMekanisme Post PartumMei RohdearniNo ratings yet

- Whe 09 3Document9 pagesWhe 09 3Gabriela MarcNo ratings yet

- Wisner Et Al - Antipsychotic Treatment During PregnancyDocument8 pagesWisner Et Al - Antipsychotic Treatment During PregnancymirasaqqafNo ratings yet

- Complex Challenges in Treating Depression During Pregnancy: Linda H. Chaudron, M.D., M.SDocument9 pagesComplex Challenges in Treating Depression During Pregnancy: Linda H. Chaudron, M.D., M.SMauro JacobsNo ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument18 pagesNIH Public AccessCorina IoanaNo ratings yet

- 2008 - Psychotropic Drugs in PregnancyDocument12 pages2008 - Psychotropic Drugs in Pregnancyotnayibor1No ratings yet

- Depression Screening During PregnancyDocument5 pagesDepression Screening During PregnancyLuvastranger Auger100% (1)

- Pregnancy Is Like The Beginning of All Things: Wonder, Hope and A Dream of Possibilities .."Document7 pagesPregnancy Is Like The Beginning of All Things: Wonder, Hope and A Dream of Possibilities .."ReshmaNo ratings yet

- E Table of Contents. Postpartum Psychosis: The Role of Women's Health Care Providers and The Health Care SystemDocument15 pagesE Table of Contents. Postpartum Psychosis: The Role of Women's Health Care Providers and The Health Care System4mdw25zqghNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Behavioral Emergencies Special Considerations in The Pregnant PatientDocument14 pages2017 - Behavioral Emergencies Special Considerations in The Pregnant PatientAna María Arenas DávilaNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Srivarshini SDocument30 pagesUnit 4 - Srivarshini Ssania.mustafa0123No ratings yet

- When Should Women Be Screened For Postnatal Depression?: EditorialDocument4 pagesWhen Should Women Be Screened For Postnatal Depression?: Editorialklysmanu93No ratings yet

- Abm Clinical Protocol 18 PDFDocument10 pagesAbm Clinical Protocol 18 PDFMarianaNo ratings yet

- Depresión 2 y Temas Que Podrían Ser de InterésDocument2 pagesDepresión 2 y Temas Que Podrían Ser de InterésYalile Venegas FernándezNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Unipolar Major Depression - General Principles of Treatment - UpToDateDocument15 pagesPostpartum Unipolar Major Depression - General Principles of Treatment - UpToDatemayteveronica1000No ratings yet

- Perinatal Psychiatric Disorders: An Overview: ObstetricsDocument15 pagesPerinatal Psychiatric Disorders: An Overview: ObstetricsAdolfoLaraRdzNo ratings yet

- Contraception For Women With Psychiatric DisordersDocument14 pagesContraception For Women With Psychiatric DisordersFourtiy mayu sariNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Disorders in PregnancyDocument4 pagesPsychiatric Disorders in PregnancyCabdiraxman Ibarahim KhalifNo ratings yet

- Perinatal Psychiatry TranscriptDocument10 pagesPerinatal Psychiatry TranscriptRitamariaNo ratings yet

- Depression During Pregnancy Rates Risks and Consequences Motherisk Update 2008Document8 pagesDepression During Pregnancy Rates Risks and Consequences Motherisk Update 2008Lastry WardaniNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Therapeutic Management Postpartum DepressionDocument2 pagesClinical and Therapeutic Management Postpartum DepressionVicky Dian FebrianiNo ratings yet

- Postpartum DepressionDocument6 pagesPostpartum Depressionapi-522555065No ratings yet

- Perinatal Psychiatric Disorders An OverviewDocument15 pagesPerinatal Psychiatric Disorders An OverviewZakkiyatus ZainiyahNo ratings yet

- PQCNC 2023 Enhancing Perinatal Mental HealthDocument10 pagesPQCNC 2023 Enhancing Perinatal Mental HealthkcochranNo ratings yet

- Becker 2016Document9 pagesBecker 2016PAULA SOFIA MORENO CASTRONo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document5 pagesAssignment 1maryamNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pearls in Perinatal Mental HealthDocument10 pagesClinical Pearls in Perinatal Mental HealthJona JoyNo ratings yet

- Maternal Age As A Factor Influencing Prenatal Distress in Indonesian PrimigravidaDocument4 pagesMaternal Age As A Factor Influencing Prenatal Distress in Indonesian Primigravidanur fadhilahNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument12 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptLecery Sophia WongNo ratings yet

- PNP 60 PDFDocument4 pagesPNP 60 PDFAndrian FajarNo ratings yet

- Enfermeria GlobalDocument12 pagesEnfermeria GlobalLuciaZanetiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Postpartum DepressionDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Postpartum Depressionea6bmkmc100% (1)

- JOURNAL PSYCHIATRIC (B.ing)Document13 pagesJOURNAL PSYCHIATRIC (B.ing)Aprilia Fani PNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between The Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression: A Study Among Cameroonian WomenDocument4 pagesRelationship Between The Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression: A Study Among Cameroonian Womendesthalia cyatraningtyasNo ratings yet

- สูติปี5 (21พค63) EPDocument51 pagesสูติปี5 (21พค63) EPNat PitchayaNo ratings yet

- Background and Purpose: Revision ProcessDocument8 pagesBackground and Purpose: Revision Processandiummul 2412No ratings yet

- Depresion Posaborto 2Document7 pagesDepresion Posaborto 2ESE HOSPITAL SAN PEDRO CLAVERNo ratings yet

- (09 17) V9N3PTDocument9 pages(09 17) V9N3PTSuba KalkiNo ratings yet

- Depression During PregnancyDocument3 pagesDepression During PregnancySellymarlinaleeNo ratings yet

- AAFP Postpartum DepressionDocument8 pagesAAFP Postpartum DepressionDrFaryal AbbassiNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Depression and Its Risk Factors in Women With A Potentially Lifethreatening ComplicationDocument18 pagesPostpartum Depression and Its Risk Factors in Women With A Potentially Lifethreatening Complicationgrace liwantoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy OnDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy OnindrasariyuliantiNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between The Baby Blues and PostpartumDocument5 pagesRelationship Between The Baby Blues and PostpartumTanu BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Childbirth Related Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocument12 pagesChildbirth Related Posttraumatic Stress DisorderMor OB-GYNNo ratings yet

- Synth Final2Document10 pagesSynth Final2api-679675055No ratings yet

- Psychopharmacology and Pregnancy: Treatment Efficacy, Risks, and GuidelinesFrom EverandPsychopharmacology and Pregnancy: Treatment Efficacy, Risks, and GuidelinesNo ratings yet

- Baby Blues: A Naturopathic Approach for Postpartum HealthFrom EverandBaby Blues: A Naturopathic Approach for Postpartum HealthNo ratings yet

- Iphone Issues On Call Set-UpDocument32 pagesIphone Issues On Call Set-UpEfosa Aigbe100% (1)

- Real Life Application of Linear AlgebraDocument9 pagesReal Life Application of Linear AlgebraSeerat BatoolNo ratings yet

- Manila Activity 1 Group 6Document5 pagesManila Activity 1 Group 6BOTIN, Kiarrah KatrinaNo ratings yet

- LED Strip Light Power Supply CalculatorDocument3 pagesLED Strip Light Power Supply CalculatorNadeem Muhammad NadzNo ratings yet

- Key Takeaways From The Topic Sexual SelfDocument2 pagesKey Takeaways From The Topic Sexual Selfshane.surigaoNo ratings yet

- CUETAdmitCard 233511034178Document2 pagesCUETAdmitCard 233511034178Sajal NahaNo ratings yet

- Taxiway Signs, Markings, LightsDocument2 pagesTaxiway Signs, Markings, Lightsapi-282893463No ratings yet

- RFCM - Compassionate Pastor Dec-2011Document44 pagesRFCM - Compassionate Pastor Dec-2011pacesoft321No ratings yet

- The Problem and Its SettingDocument7 pagesThe Problem and Its SettingLove Nowena GandawaliNo ratings yet

- AppendicesDocument12 pagesAppendicesAkosibaby FerrerNo ratings yet

- Shell Mysella S2 Z 40 Old Name R 40 PDFDocument2 pagesShell Mysella S2 Z 40 Old Name R 40 PDFhananNo ratings yet

- Tata Steel PowerDocument37 pagesTata Steel PowerChetana DiduguNo ratings yet

- 5th International Congress of Archaelogy of The Near EastDocument117 pages5th International Congress of Archaelogy of The Near EastJa AsiNo ratings yet

- How I Live Now Teach NotesDocument12 pagesHow I Live Now Teach NotesDavid Román SNo ratings yet

- Medical Parasitology LabDocument28 pagesMedical Parasitology LabJanielle Medina FajardoNo ratings yet

- IBM Blockchain Hands-On Hyperledger Composer PlaygroundDocument32 pagesIBM Blockchain Hands-On Hyperledger Composer PlaygroundPushpamNo ratings yet

- Unturned Pages of My HeartDocument47 pagesUnturned Pages of My HeartSomya TiwariNo ratings yet

- Parallel Max ServersDocument1 pageParallel Max ServersKoushik SinghaNo ratings yet

- Penyelaras Penggunaan Kemudahan Dan InventoriDocument13 pagesPenyelaras Penggunaan Kemudahan Dan InventoriIzzat D-OneNo ratings yet

- Sebm013408 A2 PRTDocument17 pagesSebm013408 A2 PRTAhmad Mubarok100% (1)

- CV Bayu Buana Natanagara Feb 2024Document4 pagesCV Bayu Buana Natanagara Feb 2024bayu.natanagaraNo ratings yet

- PertDocument52 pagesPertMuhammad FawadNo ratings yet

- View ItineraryDocument1 pageView ItineraryAbhishek NareshNo ratings yet