Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Geographic 1981-07 160-1 Jul

National Geographic 1981-07 160-1 Jul

Uploaded by

Ad Mina0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

212 views160 pagesNational Geographic 1981

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNational Geographic 1981

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

212 views160 pagesNational Geographic 1981-07 160-1 Jul

National Geographic 1981-07 160-1 Jul

Uploaded by

Ad MinaNational Geographic 1981

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 160

Re, Ne

VOL. 160, NO. 1 me JULY 1981

NATIONAL

GEOGRAPHIC

ee Ley

Ce eae Le eed

BOMBAY, THE OTHER INDIA 104

Se eC

N THE HEAT of EtSalvador’s civil war,

iB leftist leader told reporters that the

death of a journalist would “elearly ad-

vance the struggle here - _ _ so long asit was

amember of the U.S. press. You are more

powerful, more visible,”

Afew months later, photographer Olivier

Rebbot, a free lance working for Newsweek,

was killed by a sniper bullet. He was the

eighth journalist known dead or missing in

covering that war since April 1980, [t may

have disappointed hismurderers to find that

he was French, not American,

Halfa world away, Senior Assistant Edi-

tor Robert Jordan was deliberately fired

upon by-a Somalia Liberation Front unit

while preparingan article for our June issue,

In Nicaragua in 1979, the point-blank

murder bya government soldier of ABC-TV.

reporter Bill Stewart was filmed by his own

crew. Covering the world has always had its

risks, but these incidents stand #s tragic tes

timony that the loss of so many reporters in

recent vears is more than a twist of fate.

Not long ago most developing nations —

s¢nsitive to the power of pen and camera—

courted the foreign press. Today many still

see it as a powerful force, but one to be

controlled.

‘The International Press Institute counts

only 20 countries in the world with a truly

free press. Even UNESCO fired a volley at

press freedom when a studyit commissioned

recommended licensing reporters and issu-

ing ID cardsin orderto™“protect” them. This

idea, favored by Third World nations, has

been dropped for now, but it reflects in-

creasing hostility toward a free press.

This especially affects the Grocrapnic,

since we often require access to an area for

long periods of time. Increasingly, this has

become difficult or impos:

‘The Third World may justifiably feel that

some articlesdistort its problems, may be in-

sensitive or even inaccurate. We can only

hope it learns that a less-than-perfect free

press is better than none and can come to

agree with Thomas Jefferson, who said—

when we werea developing nation:

“The basis of our government being the

opinion of the people, the very first object

should be to keep that right; and were it left

to me to decide whether we should have a

government without newspapers, or news-

papers without a government, I should not

hesitate a moment to prefer the latter."

Hither E Chet

‘korea

NATIONAL

GEOGRAPHIC

July 1981

VOYAGER | AT SATURN

Riddles of the Rings 3

From a billion miles out, aa unmanned NASA

spacecraft sends home spectacular views of

the haleed planet, Rick Gore relates why the

images astounded and edified scientists. A double

supplement shows Saturn full face and to scale in

our solar system.

Costa Rica Steers the Middle Course 42

Kent Britt reports on a peaceable land of

prosperous optimism where democricy works and

armies are illegal—a true rarity amid Central

America’s masaic of strife.

Troubled Times for Central America 58

Political turmioil and violence still wrack most of

the nations of the tropical isthmus, whose promise

and problems are detailed ona foldeet map.

Living With Guanacos 63

Tens of millions of these fuurry wild camels roamed

South America until meat and pelt hunters

devastated thelr herds, Wildlife ecologist William

L. Franklin and his family spend months studying

them in remote Tierra del Fuego.

Buffalo Bill and

the Enduring West 76

A man whose nickname became a legend reatly wes

the quintessential Westerner—Pony Express rider,

Army scout, buffalo hunter, and master showman.

By Alice J. Hall, with photos by James L. Amas

Bombay, the Other India roy

From glittering skyscrapers to desperate slurs,

India’s commerciat capital ts one big paradax,

John Scofield and Raghubir Singh discover,

The Fungus That Walks 131

An oft beautiful something called slime mali lives

among us, behaving like both plant and animal

and creating micro-sculpture in the wild. Text by

Dougias Lee, photographs by Paul A. Zahl.

COVER: Multiringed Sarum glows with bands of

colar in a far-off springtime. Voyager 1 image

with colors added by NASA.

VOYAGER 1 AT SATURN

Riddles

of the

Rings

Still 18 million kilometers away,

Voyager | takes a portrait of

Saturn and two of its moons, one

casting its shadow on the cloud

tops below the rings. Shortly,

Voyager would find the bizarre

peality—puzzles in the rings and

enigmas on the moons. With

worlds yet to reveal, the

unmanned Voyager spacecraft

have proved themselves

instruments of wonder on the

frontier that forever recedes

By RICK GORE

Photographs by NASA

aon

‘SHEPHERD

Saturn's

rings

OVEMBER 10, 1980. The Voy

pacecraft is a bi

ientisisare hop at cle

hide its

ace, Some even

ve evolved on T

ying most attention,

rings. Wh

hought Gi

fe could

yager has

ever, to the

tronic eyes. The Cassini Division, a sup-

posedly clear zone between the outer A ring

nd the middle i hat least

The close-in C ring looks

dark and different.

Voyager is watching two

that se to be

round Saturn in alt

ling moon is traveling fa

and should catch up wi

s. Big, my

Piney

Sey

a

z t. The JPL pr

ems with repo

ame for the Jupite

monite to the imag

tion. Not f h ad psyched

f Jupite look cool, ethereal

N AURA OF ASTONISHMENT 1 from a distance orderly enough to have

in Pasadena, California. Twenty Saturn és a my

months earlier this same \ r hud notes Reta Beebe, a mission scientist

Liscovered so many marvels at Jupite Through even a small telescope, it’s t

plex, storm-tossed atmosphere, a thin ‘most beautiful thing in th

c m on one mo¢ {evidence Right now, to Brad Smith, t r of

fancient Earth-like crustal movements on Voyager Continued 0.

another—that its Saturn encounter hac 1 {

threatened to be anticlimactic.* er'sdazzling 3866

The rings: spoked,

tilted, and eccentric

d it to bx

Seen farther oust in’ the gre

the A ring are two brigl

ether. Between them

t begins as white

right-hand corner, When fold

upper

ise, the ringlet turns

wh

nn be roughly de

upon them

te view (right, middle) 1

lit, halfwwas t

Lapproached. Regions thick w

reflect light and thus

void of material appear dark.

Jed, halfoftheimage

ent from beneath the ring:

material

Re

tietes but also, because

of low density, all ht to pa

throu bright from ab

dark below

no fi

nsity so great that

ms. dark

tthet va

ject to perturba

bedded

The complex

pls

the rin

bur obvious. As: mission s

uct (right) points out: “t

th ture is going to to

's not something t

at jtist clic

Riddles of the Rings

Shepherd moons

imaging team, Saturn is also the most be-

deviling thing in the sky. Today he is most

baffled by those odd spokes, or fingerlike

projections, that are slightly darker than the

rings themselves and that stretch across the

Bring.

“We've never been confused for so long

about anything so obvious,” he savs, swat-

ting rolled-up paper against his palm, “It's

just so damned frustrating professionally.

‘We first saw them three weeks ago, and we

still don’t have any good ideas.”

‘These spokes emerge from theshaded side

of Saturn, sometimes in bursts of five or so,

and revolve with the rings. Gradually they

fade away, Theoretically each particle that

makes up the spokes should behave like a

mini-satellite, Those closer to Saturn should

be moving much faster than those farther

out. The spokes should tear apart. Yet they

seem to stay perfectly aligned

“Haw do they form in the first place?”

asks the frustrated Smith. “How do all those

particles know to turn dark and line them-

selves up over 25,000 kilometers?”

OVEMBER 11, 1980. Voyager is two

million kilometers from Saturn and

tonight flies within 4,000 kilometers

of Titan, More ring close-ups have come in

Life grows no simpler for Brad Smith

“The mystery of the rings keeps getting

deeper and deeper, until we think it's a bot-

tomless pit,” he saysata press briefing, “The

thing [east expected to see was an eccentric

ring—and we have found two,”

‘He flashes on a picture of one ringlet dra-

matically fatter on one side of Saturn thanon

the other (page 7)

‘Odd things too are happening out at the

thin F ring, the one being shepherded by two

little moons. Voyager images now show

clumps in the F ring. Could these clumps be

satellites trying to form? Are they moontets

being eroded? Do gravitational forces from

the shepherding satellites focus ring mate-

nial into odd-shaped regions? The mission

scientists are clearly thinking on their feet.

The F ring is close to what astrophysicists

call the Roche limit. Inside this limit the

gravitational pull from huge Saturn should

keep larue satellites from forming.

‘The Roche limit helpsexplain why Saturn

has rings. Most scientists believe that more

10

than 4.6 billion years ago, when Saturn was

forming out of thesolar nebula, it was much

larger. It collapsed suddenly, then began

spinningso rapidly that some ofits gases and.

dust were left in a flat disk around its equa-

tor, Hot, young Saturn kept this disk much

warmer than the minus 185°C (-300°F) tem-

peratures in the rings today, Heavier mate-

rials stich as metals and silicates either

coalesced into Saturn's forming moons or

swirled inward to form its deeply buried

Earth-size core, which may be molten.

As the planet shrank further, it;cooled, as

did the ring region. The water vapor that

was left there froze, says a leading theorist,

Jim Pollack, and the resulting ice crystals

gradually accreted into ring purticles

thoughtto beno morethanameterindiame-

ter, At some point a phenomenal blast of

solar wind blew away any gas that had not

yet condensed. The ring particles would

thus be the pieces of a large ice moon that

could never pull itself together.

‘There has long been a competing view,

however. Perhaps all those particles did not

form where they are today. Perhaps they

resulted from some catastrophe. The rings

could actually be the end product of a moon,

suggests mission geologist Gene Shoe-

maker. They could be a satellite smashed

to pieces by another icy body. Or perhaps

such a bedy, a traveling, homeless moon,

was torn apart by Saturn's gravity.

‘However the rings formed, most astrono-

mers believe they have been choreographed

ever since by the laws of orbital mechanics,

especially the process called resonance,

‘Through resonance the gravitational ef

fects of Saturn's moons on parts of the rings

are greatly magnified. For instance the

moon Mimas and the inner edge of the Cas-

sini Division are in resonance, Mimas takes

exactly twice as long to orbit Saturn as do.

certain Cassini particles. This regularity

means that these particles meet a slight

gravitational tug from Mimas at precisely

the same place every other orbit, Over time

that extra tug stretches their circular orbits

intoellipses, Eons ago Cassini particles thus

started to crash into particles in adjacent

orbits. Colliding particles were thrown into

other parts of the rings. Gradually a large

gap was swept out.

Before Voyager such resonances. were

National Geographic, July 1981

nsible for what little

wn. But now the

thought to be resp

structure the rings had

monitors at JPL are showing more

ture, not only in the rings but a

the Cassini Division, thanany symphony of

-es could explain.

truc-

resonant

HE NAME Peter Goldreich keeps pop-

h is not onthe Voy

ager team. He teaches at the nearby

California Institute of Technology. But of

the minds that probe the dynamics of the

solar system, his is among the very best.

Nearly two years ago in his Caltech off

he noted: “The rings of Saturn are not going

to be th ct then was U

nus. At w, very peculia

rings had recently been di round

that plan t one out from Saturn

One is only three kilometers

wide. The oute i¢; its width

varies from 20 to 100

Goldreich and Scott T

posed that it was not re

little moons, too

hat created Uran:

atellites orbiting close tog

ng up, Ge

these ri

t is eecent

nces but rather

all to be viewed

ings

therean

into

confine small particles in betw

a thin ring,” he had explai

causes each satellite to repel the

a

Gravity repel? The explan

ht

ion isa riddle

lover's deli

The lawsof ¢ han e that

satellites in higher orbits go more slowly

ian those below because they need less ve:

locity to overcome the pull

the planet. So if you have two moons with

lots of ring particles between them, theinner

on will move faster than the partic

he outer moon will move more

sider the inner moon first, Asit r

the slower ring particles, its gravity does in

deed tug at them, pulling the particles close

to it and slowing them down. But as the

ses, its gravity then starts to pull

of gravity from

mi

an

owls

ie

moon f

the particles along after it, speeding them

Because the parti ve been pulled

closer to the moon, thi lite's g

ffect on them after

Se before, So they are accel

{more than they were slowed down. Th

ting partis get a net energy gain from

the inner moon. That ene

bonsts—

Saturn: Riddles of the Rings

ncoun

At the

the kel

ron its appoii

r 2 will use

rs

2ved

outer limits of ¢}

ipa re the

ger expand aga

make some

at least to Earth.

olar wind can

fe prisgure oF

the pressure 0)

cles into at orbit

s true ter moor

svertaking it. So. as the

moon, it speeds them up and draws

ct

with the

4 are

ing them down. The particles are

closer to the moon when they start being

d. So they have a net energy |

Losing energy, they fall

The moon pushes the

yen though the moons themselves gain

dl lose energy interacting with the p

eles, resonances with other moons «

et them in their orbit

Many considered such gravitations

gamesmanship unconvineing. “It's a terri

ble thing to have to make a model when you

ed nine I tcllites that can't be

seen,” Goldreich ceded, “but Thawe

no doubt that it’s correct.”

ato

pherding moons act just like

of Uranus

lel, Coul

rturb

in his 11

ave

ible

OVEMBER 12, 1980. The tir

tinue to confound. “We

had seen all there wa:

Smith tells the press. “But

Saturn's ri

When we

s what we

become commonplace

the F ring today, th

What Smith shows is a picture of the F

ring split into three strands—two of them

uppear intertwined. They resemble a DNA

double helix. Someone jokes that Voyager

discovered life

at the > ki

Braiding defie

pics for

at Saturn, Smit

he strand:

the laws of orbital me

ihe says. “But

doing the right

ierstand the

everal reasons

iously these ring:

very well

ntion is about to be drawn away from

ight the closest images

re long. Cloud.

Titan

ry W

tures. But today begins a

zzying series of closest encounters with

Saturn's other {moe

Mimas, E Tet

Rhea, Ni tion Hyperion, Tapetis

nd Phoebe, “Too many moons,” grumbles

arty Soderblom, Until this

ek: { moons were

merely p

Project sc

nunciation. Some ss

My-mas. Some maki

und like a Mexican dish

bodies are much smaller than

s and Jupiter moons, or th

A dangerous reef

in the rings

HE 15-GENERATION GAP: For cen

turies after Franeo-T astronemer

Jean Dominique Cass what

cemed to he a gap in Saturn's rings and

sketched it (above), the Cassini Div

was thought to beaclearzone.A detail ofa

and reject

aft to Saturn,

would have

Division

and final way,

or

321 20:38:03

YORI SATURN ENC

Some tr]

Cr nr

ei

brother satellite Titan, yet larger than most

asteroids and the tiny moons around M

Jupiter, or Sate

They should be m

m:

oughly the

om 6

rial—dust and ices

should be too small to

fioactive rocky mate

bodies heats uj

geologic pro

esses suchas volcanism, These

watery moons should have frozen fast soon

after i. They

‘ked with craters, the sears of «

collisi with celestial

debris

ions

they are any-

< enough to

Iapetus to reveal much, It will

otograph Phoebe, the farthest

‘out. Phoebe has long been known totravelin

the opposite direction from Saturn's other

moons. It is most likely debris captured by

Satu by

Inpetus is perplexing. Even from Earth,

OWS ) faces. One side is five timy

ter than the other. No onereally knows

n’s gravity as it pa

it

brigh

Navigation so precise it all bur

defies

put and

nation was reg

ep the ty

ired to

course. ¥ trated work

went inte wr 10,000 possi

ble trajectories aceeraft

fis to be sorted

and

For example

enormou:

tune

Three days after Voyager 1's clos:

to Saturn, Charles

and Ray Hea

go over data for Voyager 2's en.

nter—still 283 days away, yet an

ate and pressing concern

43a navigation aid, eamputer-

enerated im ¢ the region

ere Voyager 2 witt pass between

cd Uranus (right) and its moon

reach Nept

orth pole jus

the surface

why will not

But Voyager 1 has begun s

startling features on the inner m

y the

the bland snowballs everye

cept for an eno im ppa

16-17), Its walls are five kilometers deep, its

diameter a third that of the moon. It is

among the largest craters, relative to the size

f the body hit, ever seen. Mimas came ve

ose to being blown ap:

Like the other moons, Mimas is so cold

that ice 01

putal

and Voyager it well

ms,

ast, looks the most like

xpected, ex-

t crater

ern

ju pages

n its surface is ock. “It's

This cratering has “fluffed up" or

dened" the surface to a depth of at least

several kilometers. So walking on Mim:

would bealittle like walking on a large snow

cone, with many ice chunks, some larger

than a house, sticking up from the rubble.

Farther out and much larger is Tethys. A

great branching trench 63 kilometers wi

stretches nearly from one end of this well

National Geographic, July 1981

ture. ILappea

within. Perhap:

tress y ng and expanding

terior cracked the surface of the

haps i

trench, Yet

pur

rswallowing

les of the Rir

IOVEMBER 13, 1980. Scientist Ruc

Hanel, leader of the NASA inftare

spectroscopy and radiometry team

The

ple, but

Hane!

Mimas: a satellite

nearly shattered

Meth

fer vapor is on Eart

eis only a minor

that Titan's thi

heat down below to make

There are not that many

t lar system. Titan has one be

massive enough t

tationally, Also, its

that gas

id onte gases grav

mperatures

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Gina Luker - How To Start A Home-Based Etsy Business-Globe Pequot (2014)Document239 pagesGina Luker - How To Start A Home-Based Etsy Business-Globe Pequot (2014)Ad MinaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

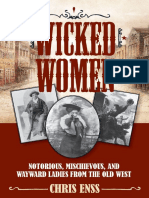

- Chris Enss - Wicked Women - Notorious, Mischievous, and Wayward Ladies From The Old West (2015, TwoDot)Document225 pagesChris Enss - Wicked Women - Notorious, Mischievous, and Wayward Ladies From The Old West (2015, TwoDot)Ad MinaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Jackie and Cassini Lauren MarinoDocument127 pagesJackie and Cassini Lauren MarinoAd MinaNo ratings yet

- St. John Bosco - Forty Dreams of St. John Bosco - The Apostle of Youth (2009, TAN Books) - Libgen - LiDocument222 pagesSt. John Bosco - Forty Dreams of St. John Bosco - The Apostle of Youth (2009, TAN Books) - Libgen - LiAd MinaNo ratings yet

- Scivias 0000 HildDocument568 pagesScivias 0000 HildAd MinaNo ratings yet

- Versace 0000 WhitDocument88 pagesVersace 0000 WhitAd MinaNo ratings yet

- National Geographic 1994-03 185-3 MarDocument172 pagesNational Geographic 1994-03 185-3 MarAd MinaNo ratings yet

- Dara Defaoíte - Paranormal Ireland - An Investigation Into The Other Side of Irish Life (2012, Maverick Publishing LTD) - Libgen - LiDocument237 pagesDara Defaoíte - Paranormal Ireland - An Investigation Into The Other Side of Irish Life (2012, Maverick Publishing LTD) - Libgen - LiAd MinaNo ratings yet

- National Geographic 1996-07 190-1 JulDocument168 pagesNational Geographic 1996-07 190-1 JulAd MinaNo ratings yet

- Management of Free-Ranging Dogs (FRD) in and Around Wildlife Protected Areas in IndiaDocument105 pagesManagement of Free-Ranging Dogs (FRD) in and Around Wildlife Protected Areas in IndiaAd MinaNo ratings yet

- Troy Deeney Troy Deeney RedemptiDocument241 pagesTroy Deeney Troy Deeney RedemptiAd MinaNo ratings yet