Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction To The System of Halachah

Uploaded by

jorge davilaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction To The System of Halachah

Uploaded by

jorge davilaCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Introduction to the System

of Halachah - Jewish Law

“The Kuzari,” a medieval book on Jewish philosophy, tells of a certain king who is disturbed by

a recurring dream of an angel telling him, “Your intentions are worthy; your actions are not.”

Whether or not we have personally experienced such a dream, we are all challenged by the

dilemma it presents: How do we know what the right course of action is? How do we convert our

noble intentions into truly moral actions?

Why Is There Halachah?

Indeed, no less than one of the greatest Sages of Jewish history faced this very problem. Rabbi

Akiva related an incident that had a strong impact on his own spiritual development:

ומצאתי מת, פעם אחת הייתי מהלך בדרך,אמר ר' עקיבא כך היה תחילת תשמישי לפני חכמים

וכשבאתי והרציתי את, וקברתיו, עד שהבאתיו למקום בית הקברות, ונטפלתי בו בארבעת מילין,מצוה

מעלה עליך כאילו שפכת, אמרו לי על כל פסיעה ופסיעה שפסעת,הדברים לפני ר' אליעזר ור' יהושע

בשעה שלא נתכוונתי, נתחייבתי, אם בשעה שנתכוונתי לזכות, למה, רבותי, אמרתי להם,דם נקי

... על אחת כמה וכמה,לזכות

Rabbi Akiva said: The following incident introduced me to the importance of

learning from Torah scholars: I was once traveling and found an unclaimed corpse. I

dealt with it, carrying it nearly four mil (Persian miles) until I found a graveyard and

buried him. When I told my teachers Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua about it,

they said to me, “Every step that you took was like an act of murder (for you should

have buried it on the spot).” I said to them, “My teachers, why, if at a time that I

intended to do something meritorious, I in fact did something blameworthy, then

how much more so when I don’t even have such honorable intentions!?” (Talmud

Bavli, Derech Eretz 8; see also Tosafot to Ketubot 17a)

Although he intended to do the right thing, due to his unawareness of the proper recourse in such

a situation, Rabbi Akiva made a mistake. How can we avoid such blunders? Rabbi Akiva’s answer,

indeed the answer Judaism has always offered to those wanting to bridge the gap between good

intentions and ethical behavior, is to learn Torah:

מאותה שעה לא זזתי מלשמש תלמידי חכמים

From that time on I did not cease from being in attendance of Torah scholars.

Judaism teaches that we are expected to “do the right thing.” “What does the Lord, your God, ask

of you?” queried Moshe (Moses), “only that you remain in awe of God your Lord, so that you will

follow all His paths and love Him” (Devarim/Deuteronomy 10:12). How do we get from the lofty

aspirations of love and awe of God to actually following His path? The only way is to follow God’s

instructions for life, the Torah.

1 The System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Where Does Halachah Come From?

The Torah offers a way of life guided by Divine law, grounded in the national revelation of the mitzvot

(commandments) at Mount Sinai, elucidated and transmitted from generation to generation throughout

the ages. In truth, though, our knowledge of God’s will dates back further than Sinai. Indeed, the very first

person, Adam, talked with God and received mitzvot from him. Noah too was told about mitzvot; he and

his immediate descendants were prophets who taught others in the name of God. Judaism itself was born

with the rediscovery of God by our Patriarch Avraham and the spiritual paths forged by his immediate

descendants. And when this family blossomed into a nation of over 2.5 million in Egypt, God took them out

under the leadership of Moshe and finally revealed His Torah to them at Mount Sinai.

The content of God’s revelations to mankind is contained succinctly in the written Torah with its history

of the world and the 613 mitzvot, followed by the writings of the Prophets. Nevertheless, without the

Oral Torah to clarify, elucidate, and interpret it into practical applications, the written Torah alone is a

closed book. Seeming contradictions abound, laws are worded vaguely, fundamental institutions are left

unexplained. And that is why the original content of the Written Torah was transmitted with an oral

explanation. An oral tradition overcomes the disadvantages of a written text by resolving ambiguity and

clarifying the original intent of the Author. At the same time it facilitates the multifaceted reading of the text

which itself remains concise, yet layered with meaning.

This oral tradition was originally meant to be transmitted by word of mouth. It was handed down from

teacher to student in such a manner that if the student had any question, he would be able to ask, and

thus avoid ambiguity. A written text, on the other hand, no matter how perfect, is always subject to

misinterpretation. Furthermore, the Oral Torah was meant to cover the infinitude of cases which would arise

in the course of time, which is why it could never have been written in its entirety. God therefore gave Moshe

a set of rules through which the Torah could be applied to every possible case.

Turning to the contents of the Oral Torah, it contains both Biblical and rabbinic law. By Biblical law we mean

the accepted tradition of proper interpretation of the Torah text. For instance, God told Moshe not to cook

a calf in its mother’s milk (chaleiv), as opposed to its mother’s fat (cheilev), even though both words have the

same Hebrew spelling in the Torah. Biblical law includes 1) any law passed directly down from Moshe, 2)

laws derived from the Torah using one of the interpretive tools (Thirteen Midot), or 3) Talmudic reasoning

(Sevarah). Examples of these three categories include 1) the type of parchment and ink used in Torah scrolls,

2) the placement of tefillin on top of the head and 3) the responsibility of the one making a financial claim to

produce proof of damage, respectively.

Aside from Biblical laws, the Sages are empowered by the Torah to introduce new laws of rabbinic nature.

These laws fall into two general categories based on the impetus behind them: (1) gezeirot – protective

enactments, and (2) takanot/minhagim – amendments/customs. Generally, a gezeirah is a law that restricts

or prohibits certain acts, while a takanah is an institution calling for the fulfillment of an act. These laws,

also passed down through the generations as part of the Oral Torah, served to safeguard the practice of the

mitzvot and to promote social welfare.

Transmission

Originally, the Oral Torah was passed on orally from teacher to student; however, safeguards were in place

to ensure its accurate transmission. While it was prohibited to formally publish works of the Oral Torah

until the Mishnah was transcribed in 200 CE, individual students kept written records of their studies. In

every generation, the leaders of the Torah academies took the responsibility of ensuring the integrity of the

transmission, buttressed by thousands of students debating and clarifying the law. The system of Semichah,

or rabbinic ordination, was developed. In order to be authorized to render halachic decisions or to carry the

The System of Halachah - Jewish Law 2

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

tradition on to the next generation, a scholar had to be ordained by someone from the previous generation

who himself had been ordained in this manner. Hence, only those who had proven themselves worthy of this

ordination were trusted to pass the tradition further.

Aside from the official teachings of the Oral Torah, the practice of halachah itself has proven to be the

greatest safeguard against distortion or loss of the Oral tradition. The careful implementation of halachah has

continued unabated since its inception some 3,300 years ago. Whether in the Land of Israel or in the lands

of the Diaspora, in good times as well as challenging periods, the Jewish people have observed the Torah

through adherence to its laws. Following the halachah has always been seen as a direct fulfilment of God’s

wishes. The desire to do God’s will alone has been the binding force of halachah throughout the ages.

There is a well-known Hasidic tale that recounts that, one Passover eve, the Berditchever Rebbe

announced that he would not begin the Seder until a quantity of outlawed Turkish wool, Austrian

tobacco and Oriental silk were brought to him from within the Jewish village. Within a short time

everything that he requested was procured. Thereupon, he announced that one additional item

was required: a crust of bread. His disciples were taken aback by this strange request but they

unquestioningly set out to fulfil their master’s command. They scoured the town, but to no avail – they

were forced to return empty-handed. The Berditchever listened in silence as they reported their lack

of success. Then, with a smile enveloping his face, he raised his hands and exclaimed, “Master of the

Universe! The Russian Czar deploys thousands of guards to patrol his borders, employs countless

numbers of police officers in order to enforce his edicts and administers a vast penal system to punish

those who violate his laws. But look at the contraband that can be found within his borders! You, Master

of the Universe, have no guards, no police, and no prisons. Your only weapon is a brief phrase in the

Torah, forbidding Jews to retain chametz (leavened bread) in their possession on Passover, but not a bit

of chametz can be found in all of Berditchev!” (Rabbi J. David Bleich, Contemporary Halachic Problems,

Vol. 3, pp. xiii-xiv).

Codification and Publication

משה קבל תורה מסיני ומסרה ליהושע ויהושע לזקנים וזקנים לנביאים

)א:ונביאים מסרוה לאנשי כנסת הגדולה…(פרקי אבות א

Moshe received the Torah from Sinai and gave it over to Yehoshua. Yehoshua gave it over to

the Elders, the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets gave it over to the Men of the Great

Assembly… (Pirkei Avot/Ethics of the Fathers 1:1)

The oral method of transmission lasted fifteen hundred years from the time of the giving of the Torah in 1312

BCE until the final redaction of the Mishnah in approximately 200 CE. The actual process of committing the

Oral Torah to writing did not happen overnight. It stretched over several centuries starting with the Men of

the Great Assembly, the leaders of the nation around the time of the construction of the second Temple (fifth

century BCE). These Sages codified much of the Oral Torah in a system that facilitated its memorization,

organizing in it into treatises and chapters.

This codification was known as the Mishnah. One reason for this name was that it was meant to be

repeatedly reviewed (shana) until memorized. The final, most precise and authoritative redaction of the Oral

Torah was engineered by Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi (Judah the Prince) around 200 CE. At this time, a great

conference of the leading Sages reviewed, ratified, and codified everything that had been transmitted as the

Oral Torah.

The writing of the Mishnah was a historical necessity to prevent the Oral Torah from being lost. With the

3 The System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

loss of sovereignty of the Land of Israel to the Romans, the destruction of the Temple and the exile of many

Jews, rabbis did not have the peace of mind required for the great demands of mastering the Oral Torah. The

legal basis for publishing the Oral Torah came itself from a verse in Scripture: “There is a time to act for God;

they voided Your Torah” (Tehillim/Psalms 119:126). This verse implies that when the Torah is in danger of

becoming forgotten, it is a time to take action for the sake of God, even by means normally forbidden.

As the socio-political situation of the Jewish people continued to deteriorate under Babylonian and Roman

rule in the Second through Fourth Centuries, eventually the Oral Torah required the publishing of further

elucidation to ensure its survival. The Talmud was therefore developed to serve as a record of the debates and

logic that underpinned the rulings of the Mishnah. It also recorded developments in rabbinic law, as well as

Aggadata – the philosophical and ethical teachings of the Oral Torah.

The historical circumstances in which the Talmud was written and the consensus that developed around it

invest it with the ultimate authority in Jewish law. Political conditions were favorable in Babylon during the

years just before the writing of the Talmud. This enabled a massive convention of all the world’s recognized

Torah scholars, where they were able to compare notes and come up with decisions. Since this convention

was so comprehensive and exhaustive, the conclusions that were formed there became absolutely binding.

Dynamics of Dispute

Why were “decisions” necessary in the first place? Aren’t we talking about a body of knowledge passed down

through the generations – what needed to be decided? Actually, the Oral Torah is not just a body of law. It is

also a system of law with its own unique methodology that can lead to multiple legal outcomes. The Torah

itself empowered the Sages to determine stances in Jewish law. Even Moshe himself was taught different ways

of resolving legal matters, and he left many issues for future generations to analyze and then determine the

halachic practice for themselves. This process of determining the halachah is characterized by disagreements

among Talmudic sages. Yet, the Talmud ascribes to the notion that even legal opinions not accepted as

halachah have credibility in Heaven: “These and these are the words of the living God” [Eruvin 13b]. As

such, many views were recorded in the Mishnah, even though they were rejected in practice, simply because

they are also considered “the words of the living God.”

Historically, differing legal opinions were resolved as Torah law through a court system that worked by

majority rule. For this reason, disputes were few and short lasting. In Temple times, the Sanhedrin, or Jewish

Supreme Court, sat in the Temple compound and issued ruling in Jewish law based on majority vote of its

Sages. These were scholars of the highest rank who had mastered the Oral Torah and integrated it within

their own personalities with the utmost integrity. However, because of the oppression of the conquering

powers and the harsh decrees imposed, it became more difficult for the Sages to concentrate well enough to

clarify the disputes. Differences of opinion became more rampant until the time of the Mishnah. Moreover,

the increased number of disputes was attributed to the students’ failure to adequately study under their

Torah mentors and to learn from their personal examples.

The first ongoing disputes were few in number. However, with the development of the academies of Hillel

and Shammai (first century BCE), the disciples differed on many fine points of Jewish law; disputes became

so prevalent that there appeared to be two distinct schools of thought regarding Jewish law.

Oppression temporarily subsided in the days of Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi. This great sage and leader found

favor in the eyes of the governing Romans and was able to convene a mass assemblage of Torah scholars

to debate and discuss all that was known of the Oral Torah to date. The disputes were clarified and often

resolved. While the Mishnah still records many of these disputes, Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi arranged the

Mishnah in such a way that it would be known which opinion was accepted as halachah. For instance,

an opinion recorded anonymously takes precedent over one attributed to a particular sage. Furthermore,

The System of Halachah - Jewish Law 4

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

documenting disputes was necessary in order to maintain a record of minority opinions that might be relied

upon in the future.

It should be noted that even with the publication of the Mishnah, the Oral Torah remained largely oral, in

need of those who had mastered it to teach it to the next generation. It is true that with the compilation of

the Mishnah many disputes were clarified and often resolved. The Mishnah records many of these disputes,

but it is arranged in such a way that the accepted opinion could be gleaned simply by the structure in which

it was presented. However, the correct interpretation of the Mishnah was not always agreed upon. Eventually

the Talmud developed to explain the disputes in the Mishnah, a process that itself led to more disputes.

Similarly, Talmudic commentators emerged to explain how the halachah was to be concluded from its

discussion in the Mishnah and the Talmud. And so the process of dispute and debate continued, and persists

to this very day.

The Structure of Jewish Law

The development of the Oral Torah, with all of its dynamics of disputes and decisions, did not stop with

the sealing of the Talmud. It has developed in stages throughout Jewish history. Starting with the Mishnah

and the Talmud, then the Rishonim, Acharonim and Shulchan Aruch, each phase has established binding

precedents for those that follow.

While the Talmud is the first word in Jewish Law, it is not the last. Even though its authority cannot be

disputed, the Talmud nevertheless was not written as an organized reference book of laws. It is very hard to

extract practical halachah from it without complete mastery of it in its entirety. Over time, this difficulty led

to the eventual codification of Talmudic law in the Middle Ages by Rambam (Maimonides) and others. The

Sages of this later period, up to the publication of the Shulchan Aruch, the Code of Jewish Law, are called

the Rishonim (First-Stage Scholars: 11th – 15th centuries). Their works served as precedents and as bases for

further elucidation of the halachah by the Acharonim (Later-Stage Scholars: 16th – 19th centuries). And the

process continues to this day, when present-day rabbis apply Torah law to new questions as they arise, based

on the legal principles of the Oral Torah and the precedents set by the rulings of earlier authorities. In this

sense, halachah functions as a living system of law not unlike other contemporary legal systems.

The structure of Jewish law is in many ways analogous to that of Western legal systems. While

the analogy is somewhat simplistic, it is instructive to give a sense of how the halachic process

is organized. Just as the written basis of the United States legal system is the constitution, the

Torah is the basis of the halachic system…Like any Western legal system, our laws are compiled

into statute books. Just as there are tomes of federal and state laws, we have compilations of

Jewish law dating back over 800 years. The earliest extensive organized compilation of Jewish

law was performed by Moses Maimonides, a great rabbi and physician of the 12th century. His

Yad HaChazaka, also known as the Mishnah Torah, covers all areas of Jewish law and remains

one of the most authoritative legal guides in Judaism. The next great statute book, the Arbah

Turim, was written by Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher in the early 14th century. Probably the most

famous compilation of Jewish law is the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law), written by the

Sephardic Posek (halachic decision maker) Rabbi Yosef Karo, who lived in Safed, Israel, with

glosses by the Polish Ashkenazi Posek Rabbi Moshe Isserles. This seminal work was completed

in the late 16th century, and while hundreds of subsequent commentaries have been written,

it remains the preeminent guide to Jewish law. (Daniel Eisenberg, MD, “Why Jewish Medical

Ethics,” www.aish.com)

5 The System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Hi Tech / Low Tech – Halachah is Eternally Relevant

Many of us may become aware of halachah, Jewish law, from life cycle events – through interactions with

rabbis and observant Jews during a Brit Milah (circumcision ceremony), Bat and Bar Mitzvah, weddings and

funerals. And we may think that, aside from additional customs related to commemorating Jewish festivals,

these events are the full extent of Jewish law. However, what might be less known is that halachah is the

profound expression of our relationship with an infinite God, and as such permeates every aspect of life.

The Industrial Revolution, the advent of high-speed travel, rapid advancements in electricity and technology

have changed our world so much. Since the Talmud and Rishonim obviously did not discuss these things,

contemporary scholars have applied the Talmud’s principles to our modern lifestyle and thereby rule on the

halachah as it pertains to all these new nuances of lifestyle.

The contemporary Torah scholar searches for precedents in the works of earlier Poskim (halachic decision

makers) whenever he needs to issue a ruling, much as a lawyer or judge searches for precedents for a

legal decision. In order to be able to render a ruling on something new, the scholar must be eminently

familiar with the Talmud, its commentaries, the Arbah Turim , the Beit Yosef and Shulchan Aruch and its

commentaries, besides the enormous volume of halachic responsa that grows larger with each passing

generation.

Regardless of how unique a situation may appear, the approach of the halachic system remains

unchanged. As the book of Ecclesiastes states: “There is nothing new under the sun.” Infertility

treatments (including IVF and surrogacy), artificial prolongation of life, abortion, rationing,

self-endangerment, and a myriad of other contemporary ethical issues have been dealt with in

Jewish law for millennia. The challenge is to appropriately recognize the salient issues in order

to properly apply Jewish law. (Daniel Eisenberg, MD, “Why Jewish Medical Ethics,” from www.

aish.com).

Jewish law is a comprehensive, methodological system that applies to the entire Jewish people. Although

there is one master framework, worldwide dispersion has led to rabbinic legislation that now reflects

differences between Sephardim, Ashkenazim, and Yemenites. Moreover, legal rulings may differ depending

on unique circumstances of a given case. For example, the communal observance of Yom Kippur requires

fasting as part of the introspection and repentance of the day, but a person with a life-threatening medical

condition is obligated to eat and drink to preserve his life. Consequently, when questions arise, there is

a prerequisite to seek a qualified Posek, who will thoroughly examine each situation to provide personal

halachic guidance.

The Way to Go!

Through the Oral Torah in all its written manifestations as we have them today – the Mishnah, Talmud,

Rishonim, Acharonim, and contemporary Poskim – the Written Torah is transformed into a practical system

for living. In short, it becomes halachah, the Hebrew word for Jewish law derived from the term halach,

meaning “to go” or “to walk.” The halachah teaches us how to go through this world, how to walk the

straight path before God. Jewish law guides nearly every aspect of human endeavor and interaction so that

we may achieve our essential missions in life – to perfect our character, develop a relationship with God, lead

an ethical life, raise productive families, and build a just, meaningful world.

Many people claim, “I’m a good person; I have values. Isn’t that sufficient?” Values are nice, but they cannot

guarantee that we will always make the right decisions. For that, we need instructions, the manual given by

the Creator to mankind to guide them through life. That is the Torah – Written and Oral – and halachah is

the way the Torah is put into action.

The System of Halachah - Jewish Law 6

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

The halachah, which was given to us from Sinai, is the objectification of religion in clear and

determined forms, in precise and authoritative laws, and in definite principles. It translates

subjectivity into objectivity, the amorphous flow of religious experience into a fixed pattern of

lawfulness. (Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Halachic Man, pg. 59)

Ethical behavior is therefore given to absolute standards. Getting 90% on an exam may be praiseworthy,

but someone who in principle is moral 90% of the time – and does whatever he wants the rest of the time

– is not moral at all. So too, someone who steals even small amounts, or who robs from those with a lot of

money, is still a thief even if he would never dream of stealing larger amounts or from people who couldn’t

afford it.

For this reason, halachah is precise down to the last detail. This can be compared to other systems in the

physical world, when even a small detail is lacking, the entire structure ceases to function. Take a car, for

example. It is a large and complex system, yet if even the smallest working part is removed, the car will not

operate. The laws of the Torah are a spiritual reality and its complexity demands no less attention to detail

than our physical reality does. Halachah therefore applies the mitzvot of the Torah to every facet of our lives

with the attention to detail required for truly ethical living. (Rabbi Mayer Twersky, Why Halacha is Focused

on Details, www.yutorah.org)

From a traditional Jewish approach, Jewish Law, Halachah, defines ethics. Halachah is the code

of conduct by which the traditional Jew leads his or her life. Extra-halachic ethics is somewhat

of a non-sequitur. We apply Jewish law to each case and the answers that we reach should

represent an ethical paradigm. For this reason, Jewish medical ethics is merely the application

of Jewish law to medicine, just as kashrut is the application of Jewish law to food, or Jewish tort

law is the application of Jewish law to monetary damages. (Daniel Eisenberg, MD, “Why Jewish

Medical Ethics,” from www.aish.com)

When the Jewish people keep the Torah through the system of halachah, they are able to walk the straight

path before God. By virtue of this system, they are able to avoid the pitfalls of subjective values, of misguided

religious fervor, and even of good intentions.

Contents of the Morasha Series on the System of Halachah

The Morasha System of Halachah Series seeks to explain the foundation, development, transmission,

integrity and contemporary application of Jewish law. We also seek to understand the relationship between

the Written and Oral Torahs, the role of the Prophets, rabbinic authority, machloket (dispute), as well as the

rabbis’ mandate to interpret the Torah and legislate new laws. The series consists of eight classes and are

organized as follows:

I. The Revelation of Torah

Section I. The Heritage of Humanity

Section II. The Avot (Forefathers)

Section III. The Exodus and Buildup to Mount Sinai

Section IV. Mount Sinai

Section V. Forty Years in the Desert

Section VI. The Book of Devarim (Deuteronomy)

Section VII. The Prophets

7 The System of Halachah - Jewish Law

Introduction to the System of Halachah - Jewish Law

II. The Written Torah, the Oral Torah, and their Interrelationship

Section I: The Two Torahs: Written and Oral

Section II. Relationship between the Written and Oral Torahs

Section III. Why the Oral Torah was Written Down

III. The Contents of the Oral Torah

Section I. Legal Component of the Oral Torah

Section II. Philosophic Component of Oral Torah – Aggadata

Section III. The Oral Torah in Writing - Redactions

IV. Necessity, Advantages and Accuracy of the Oral Torah

Section I. Necessity of the Oral Torah

Section II. Advantages of Having the Oral Torah

Section III. Accuracy of the Transmission

V. The Chain of Torah Transmission

Introduction. A Daily Workout with Great Personal Spiritual Trainers

Section I. Overview – The Many Unbroken Chains of Transmission

Section II. The Biblical Period

Section III. The Talmudic Period

Section IV. The Post-Talmudic Period

VI. Rabbinic Authority

Introduction. The Three Hats of Rabbinic Attire

Section I. The Qualifications of the Sages

Section II. Sages as the Carriers of the Explanations of Torah Law

Section III. The Sages as Interpreters of the Torah to Establish Laws

Section IV. The Sages as Legislators of Rabbinic Law and Decrees

VII. The Concept and Dynamics of Machloket – Dispute

Section I. The Origin of Disputes

Section II. The Nature of Disputes

Section III. Both Sides are Right (Eilu ve’Eilu)

Section IV. Machloket in Contemporary Rulings

VIII. The Halachic Process

Section I. The Stages of Halachah

Section II. Sample Halachic Process: Visiting the Sick

The System of Halachah - Jewish Law 8

You might also like

- A Map of the Universe: An Introduction to the Study of KabbalahFrom EverandA Map of the Universe: An Introduction to the Study of KabbalahNo ratings yet

- Hebraic Literature: Translations from the Talmud, Midrashim and KabbalaFrom EverandHebraic Literature: Translations from the Talmud, Midrashim and KabbalaNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From "The Divine Code" by Rabbi Moshe WeinerDocument6 pagesExcerpts From "The Divine Code" by Rabbi Moshe WeinerChristophe Mazières100% (1)

- The Talmud - A Gateway To The Common LawDocument46 pagesThe Talmud - A Gateway To The Common LawKatarina ErdeljanNo ratings yet

- Sor Notes-JudaismDocument8 pagesSor Notes-JudaismJohnNo ratings yet

- What Is Zohar in Kabbalah According To The Previous ScholarsDocument5 pagesWhat Is Zohar in Kabbalah According To The Previous ScholarsNaalain e SyedaNo ratings yet

- Daas Torah: The Role of A Talmid Chacham in SocietyDocument4 pagesDaas Torah: The Role of A Talmid Chacham in SocietygavNo ratings yet

- Emor 4:7:23Document7 pagesEmor 4:7:23Kenneth LickerNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument24 pagesUntitledoutdashNo ratings yet

- Rav Soloveitchik-The Common-Sense Rebellion Against Torah AuthorityDocument6 pagesRav Soloveitchik-The Common-Sense Rebellion Against Torah AuthorityTechRav100% (7)

- World Religions PowerpointDocument96 pagesWorld Religions Powerpointjeffpatten100% (13)

- Toronto TorahDocument4 pagesToronto Torahoutdash2No ratings yet

- Guiding Immigrants with Jewish TeachingsDocument2 pagesGuiding Immigrants with Jewish TeachingsDaniel ChrysNo ratings yet

- Hebraic Literature; Translations from the Talmud, Midrashim and KabbalaFrom EverandHebraic Literature; Translations from the Talmud, Midrashim and KabbalaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionDocument19 pagesFundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionYoel Ben-AvrahamNo ratings yet

- The Ways of ReasonDocument12 pagesThe Ways of ReasonAntonio LimasNo ratings yet

- Radicals, Rebels, & Rabblerousers: 3 Unusual Rabbis - #1 R. Shmuel AlexandrovDocument8 pagesRadicals, Rebels, & Rabblerousers: 3 Unusual Rabbis - #1 R. Shmuel AlexandrovJosh RosenfeldNo ratings yet

- Oral Law-Not So Fun Facts!Document81 pagesOral Law-Not So Fun Facts!Justin EmmonsNo ratings yet

- Toronto TorahDocument4 pagesToronto Torahoutdash2No ratings yet

- Teaching The Mesorah: Avodah Namely, He Is Both A Posek (Halachic Decisor) and An Educator For The EntireDocument5 pagesTeaching The Mesorah: Avodah Namely, He Is Both A Posek (Halachic Decisor) and An Educator For The Entireoutdash2No ratings yet

- Traditia Orala FileDocument18 pagesTraditia Orala FilecristiannicuNo ratings yet

- Discipleship Is JewishDocument9 pagesDiscipleship Is JewishHugo MartinNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Iberian Anusim - SCJSDocument40 pagesTreatment of Iberian Anusim - SCJSdramirezg100% (16)

- Pirke Avot (English-Hebrew)Document171 pagesPirke Avot (English-Hebrew)Bibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNo ratings yet

- The Enduring Meaning of The Covenant of The PatriarchsDocument4 pagesThe Enduring Meaning of The Covenant of The Patriarchsoutdash2No ratings yet

- Kabbalah for Beginners: An Introduction to Jewish MysticismFrom EverandKabbalah for Beginners: An Introduction to Jewish MysticismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- A Historical Research of The Ten TribesDocument57 pagesA Historical Research of The Ten TribesDavidChichinadze100% (1)

- Ghulam Ahmad ParwezDocument6 pagesGhulam Ahmad Parwezapi-26737352No ratings yet

- Paul's High View of Torah LawDocument9 pagesPaul's High View of Torah LawRoxana BarnesNo ratings yet

- Secret of Brit BookDocument33 pagesSecret of Brit BookDavid Saportas Lièvano100% (1)

- Hebraic Literature Translations From The Talmud, Midrashim Andkabbala by VariousDocument271 pagesHebraic Literature Translations From The Talmud, Midrashim Andkabbala by VariousGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Inaugural Address of Solomon SchechterDocument32 pagesInaugural Address of Solomon SchechterdeblazeNo ratings yet

- Nderstanding Rabbinic Midrash/: Texts and CommentaryDocument11 pagesNderstanding Rabbinic Midrash/: Texts and CommentaryPrince McGershonNo ratings yet

- Thinking Like A Hebrew by Morris SalgeDocument14 pagesThinking Like A Hebrew by Morris SalgeSandra Crosnoe100% (1)

- Toward a Meaningful Life: The Wisdom of the Rebbe Menachem Mendel SchneersonFrom EverandToward a Meaningful Life: The Wisdom of the Rebbe Menachem Mendel SchneersonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Repentance As FreedomDocument4 pagesRepentance As Freedomoutdash2No ratings yet

- Noahide-Ancient-Path Co Uk-The Path of The Righteous Gentile EbookDocument73 pagesNoahide-Ancient-Path Co Uk-The Path of The Righteous Gentile Ebookapi-268900674100% (1)

- CHABAD CHASSIDUS - Various AspectsDocument25 pagesCHABAD CHASSIDUS - Various AspectsRabbi Benyomin Hoffman100% (1)

- The Chanukah Controversy and Its Relevance Today: Rabbi Laurence Doron PerezDocument9 pagesThe Chanukah Controversy and Its Relevance Today: Rabbi Laurence Doron Perezoutdash2No ratings yet

- 889Document40 pages889B. MerkurNo ratings yet

- Shalom for the Heart: Torah-Inspired Devotions for a Sacred LifeFrom EverandShalom for the Heart: Torah-Inspired Devotions for a Sacred LifeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4-A Brief History of Hermeneutics-CompletedDocument35 pagesChapter 4-A Brief History of Hermeneutics-CompletedArockiaraj RajuNo ratings yet

- TalmudDocument6 pagesTalmudnsalahNo ratings yet

- The God We Believe in - Ariel Edery's ArticleDocument6 pagesThe God We Believe in - Ariel Edery's ArticleAriel EderyNo ratings yet

- Shaar HaEmunah Ve'Yesod HaChassidut - en - Merged - PlainDocument159 pagesShaar HaEmunah Ve'Yesod HaChassidut - en - Merged - PlainJesse GlaserNo ratings yet

- Israel and HumanityDocument187 pagesIsrael and HumanityRoberto Y TenganNo ratings yet

- 06 Chapter2 Religions PDFDocument9 pages06 Chapter2 Religions PDFCaroline L M FlowerNo ratings yet

- Kitzur Shul'Han ArujDocument357 pagesKitzur Shul'Han ArujEdiciones Yojéved100% (2)

- ChasidotDocument5 pagesChasidotcarlos incognitosNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Judaism from Ezra to the Present: Part One: Pharisaic JudaismFrom EverandThe Evolution of Judaism from Ezra to the Present: Part One: Pharisaic JudaismNo ratings yet

- Biblical Characters and Judaism Explained in Under 40 WordsDocument29 pagesBiblical Characters and Judaism Explained in Under 40 WordsMelisa Cantonjos100% (2)

- 613 LawsDocument15 pages613 Lawsdavidpchristian100% (1)

- Jewish Wisdom: The Wisdom of the Kabbalah, The Wisdom of the Talmud, and The Wisdom of the TorahFrom EverandJewish Wisdom: The Wisdom of the Kabbalah, The Wisdom of the Talmud, and The Wisdom of the TorahNo ratings yet

- From the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)From EverandFrom the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)No ratings yet

- August 24 Shabbat Announcements Great Neck SynagogueDocument4 pagesAugust 24 Shabbat Announcements Great Neck SynagoguegnswebNo ratings yet

- Shabbat Morning Inc Rosh Hodesh Musaf and Hallel SIDDUR SIM SHALOMDocument255 pagesShabbat Morning Inc Rosh Hodesh Musaf and Hallel SIDDUR SIM SHALOMjorge davilaNo ratings yet

- Bialik Halacha and Aggadah-1Document24 pagesBialik Halacha and Aggadah-1jorge davilaNo ratings yet

- Siddur StapleDocument29 pagesSiddur StapleKamil NovotnyNo ratings yet

- Effects of Music On Psychological Arousal Tempo and GenreDocument26 pagesEffects of Music On Psychological Arousal Tempo and GenreMiassssNo ratings yet

- BGLG 73 20 Tetzaveh 5773Document44 pagesBGLG 73 20 Tetzaveh 5773api-245650987No ratings yet

- HaAzinu - Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinDocument2 pagesHaAzinu - Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Headlines: Halachic Debates of Current EventsDocument18 pagesHeadlines: Halachic Debates of Current EventsChabad Info EnglishNo ratings yet

- VaYeira Shem MishmuelDocument5 pagesVaYeira Shem MishmuelPracticleSpiritNo ratings yet

- Sample of PBM PDFDocument17 pagesSample of PBM PDFmichaelchaimgreenNo ratings yet

- Lauterbach-Midrash and Mishna-1916 PDFDocument132 pagesLauterbach-Midrash and Mishna-1916 PDFphilologusNo ratings yet

- 1012Document32 pages1012Beis MoshiachNo ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Eruvin 97: A Knotty Problem: Yona Wallach, Tefillin From Wild Light 1983Document36 pagesDaf Ditty Eruvin 97: A Knotty Problem: Yona Wallach, Tefillin From Wild Light 1983Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- EJ Midreshei HalakhahDocument12 pagesEJ Midreshei HalakhahBenjamin CrowneNo ratings yet

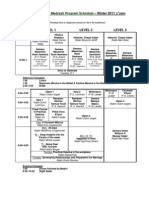

- IBMP Schedule Winter 2011Document2 pagesIBMP Schedule Winter 2011yehoshuadovidNo ratings yet

- HeptarchiaDocument5 pagesHeptarchiamaxNo ratings yet

- Torah Wellsprings - Bo 5780 A4Document21 pagesTorah Wellsprings - Bo 5780 A4Boat DrinXNo ratings yet

- Charles R. Gianotti-The New Testament and The Mishnah - A Cross-Reference Index-Baker (1983) PDFDocument63 pagesCharles R. Gianotti-The New Testament and The Mishnah - A Cross-Reference Index-Baker (1983) PDFVladimir CarlanNo ratings yet

- Curse Israel Ritual by High Priestess Maxine DietrichDocument2 pagesCurse Israel Ritual by High Priestess Maxine DietrichKoty StrongburgNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument269 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Taanis 12: Personal Trials and FastingDocument54 pagesDaf Ditty Taanis 12: Personal Trials and FastingJulian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- CSZ Autumn 2014 RecorderDocument32 pagesCSZ Autumn 2014 RecorderWilliam ClarkNo ratings yet

- Sukkah 51Document81 pagesSukkah 51Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Significance of Numbers in JudaismDocument10 pagesSignificance of Numbers in Judaismnieotyagi0% (1)

- Likutei Ohr: A Publication of YULA Boys High SchoolDocument2 pagesLikutei Ohr: A Publication of YULA Boys High Schooloutdash2No ratings yet

- Maimonide’s Division of the 248 Positive MitzvotDocument16 pagesMaimonide’s Division of the 248 Positive MitzvotAlma SlatkovicNo ratings yet

- Holiness in Time Introduction To The Jewish CalendarDocument6 pagesHoliness in Time Introduction To The Jewish Calendaroutdash2No ratings yet

- TLS KabShab Guitar ChordsDocument6 pagesTLS KabShab Guitar ChordsBob BaoBab100% (1)

- October 17, 2015 Shabbat CardDocument12 pagesOctober 17, 2015 Shabbat CardWilliam ClarkNo ratings yet

- Sacrifice and Sanctification: LeviticusDocument16 pagesSacrifice and Sanctification: LeviticusshaqtimNo ratings yet

- Lesson 21 - Torah Study IIDocument9 pagesLesson 21 - Torah Study IIMilan KokowiczNo ratings yet

- Noam Elimelech Moadim SampleDocument12 pagesNoam Elimelech Moadim Sampletalmoshe613No ratings yet

- Kedoshim Selectons From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinDocument4 pagesKedoshim Selectons From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Zionist HaggadotDocument4 pagesZionist Haggadotjezg1No ratings yet