Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 EatingRaoul CannibalCulture

3 EatingRaoul CannibalCulture

Uploaded by

Shamma AlkhooriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 EatingRaoul CannibalCulture

3 EatingRaoul CannibalCulture

Uploaded by

Shamma AlkhooriCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter Title: Cannibal Culture

Book Title: Our Cannibals, Ourselves

Book Author(s): PRISCILLA L. WALTON

Published by: University of Illinois Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1xcgrz.11

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Our Cannibals, Ourselves

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

7. Cannibal Culture

Expanding on the theme of the killer next door in the 1980s, a decade syn-

onymous with junk bonds, savings and loan scandals, and business mergers

and takeovers (all of which foregrounded an economy that seemed to be

cannibalizing itself), a small-budget, independent film appeared and, accord-

ing to Nick Martin and Marsha Porter, offered an “inventive but rather bi-

zarre solution to the recession” (319). Viewed in this light, Paul Bartel’s 1982

Eating Raoul embodies a microcosm of the political macrocosm, a small-time

response to a big-time movement, a movement that figuratively cannibalizes

the weak to fortify the strong.

Eating Raoul, a tongue-in-cheek black comedy, traces the dilemma of an

“average” couple searching for their piece of the American dream. Mary and

Paul Bland long to buy a restaurant, but hard times have left them with dwin-

dling resources. To resolve their financial troubles (and raise a downpayment

on a potential business property), the two devise a quick-money scheme:

Mary will pose as a prostitute and Paul will kill her would-be customers by

hitting them over the head with a frying pan. In this way, the two can help

themselves to the dead men’s wallets while leaving Mary’s “virtue” uncom-

promised. Paul and Mary muddle through their new enterprise until their

secret is discovered by a locksmith, Raoul, who wants in on the scam, offer-

ing to dispose of the bodies to earn his share of the profits. Raoul’s contri-

bution lends the scheme a much-needed “removal” service, and business

starts to boom. Unfortunately, along the way Raoul falls in love with Mary,

threatening the venture and Paul’s equilibrium. In a fit of jealousy, Paul kills

Raoul and is left, again, with a disposal dilemma. That night, having reached

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

142 our cannibals, ourselves

their downpayment goal, Paul and Mary throw a dinner party to celebrate

the purchase of their restaurant property. The meal they prepare serves both

as a celebratory feast and as a solution to “the Raoul problem,” for it features

Raoul as a main ingredient. The dinner consists of a new dish that Mary plans

to offer in “Paul & Mary’s Country Kitchen.” This specialty, which incorpo-

rates Raoul’s flesh, is a big hit: Paul finds it a little “spicy,” but Mary wistful-

ly notes that the meat is “oh, so tender.” Concluding the film, the camera

frames Paul and Mary as they contemplate a happy future together as res-

taurateurs.1

Metaphorically, Eating Raoul demonstrates how money and success can

be actualized through the consumption of others.2 That Raoul is Chicano is

significant, for, as I have discussed throughout, the racial minority often is

cast as the instigator of the anthropophagy (in this case, it is Raoul’s idea to

dispose of the corpses by selling them to a dog food company) and ultimately

he who serves as the devoured. Where The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her

Lover effects a taking back of power through cannibalism, Eating Raoul fol-

lows the more traditional pattern of eating the Other to consolidate one’s own

power.

As Martin and Porter imply, then, Bartel’s “simple” film combines the

drives predominant in the 1980s, an era when sex, death, and financial gain

were perhaps more inextricably intertwined than in earlier decades. It is also

chronicled in Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho and Mary Harron’s

2000 film adapted from it. Labeled by one critic as the “quintessential ’80s

text” (Kevin Dowler, personal communication, 1994), Ellis’s work metabo-

lizes life in the center of money and power: New York City in the mid-1980s.

Designer Cannibalism

Although American Psycho’s documentation of grisly killing sprees shocked

audiences and led to its censorship in several countries,3 leaving aside the

protagonist’s unusual extracurricular activities, in all other respects Patrick

Bateman conforms to an image of the perfect 1980s man. Bateman has gone

to all the right schools, knows all the right people, and has the right job: As

an investment banker, he is the epitome of success in the 1980s. Running

throughout the text are lists of the merchandise that establishes Bateman’s

life as an all-around triumph; these commodities spell achievement (through

their designer labels) in the 1980s: “I’m wearing a six-button double-breast-

ed chalk-striped suit by Ralph Lauren with a spread-collar pencil-striped Sea

Island cotton shirt with French cuffs, also by Polo. . . . I check myself in the

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 143

mirror . . . go back to my briefcase for some mousse to slick my hair back and

then I use a moisturizer and, for a small blemish I notice under my lower lip,

a dab of Clinique Touch-Stick” (68). Bateman has a great apartment, a beau-

tiful fiancée, a sensual mistress, and access to all the current hot spots. In-

deed, much of the book is devoted to where Patrick will spend his mealtimes

and to his assessments of how others fit in with the decor: “Evelyn stands by

a blond wood counter wearing a Krizia cream silk blouse, a Krizia rust tweed

skirt and the same pair of silk-satin d’Orsay pumps Courtney has on. Her

long blond hair is pinned back into a rather severe-looking bun and she ac-

knowledges me without looking up from the oval Wilton stainless-steel plat-

ter on which she has artfully arranged the sushi. ‘Oh honey, I’m sorry, I want-

ed to go to this darling little new Salvadorian bistro on the Lower East Side’”

(9).

Not surprisingly, given their importance to Bateman, the consumer ves-

tiges of success, or rather the lack of them, send him into murderous rages.

In one scene, he is driven to plot a colleague’s murder because that colleague’s

business card is more impressive than his own. That Bateman could be out-

done on such a “significant” matter leaves him aghast:

I’m looking at Van Patten’s card and then at mine and cannot believe that Price

actually likes Van Patten’s better. Dizzy, I sip my drink then take a deep breath.

. . . I pick up Montgomery’s card and actually finger it, for the sensation the

card gives off to the pads of my fingers.

“Nice, hunh?” Price’s tone suggests he realizes I’m jealous.

“Yeah,” I say offhandedly, giving Price the card like I don’t give a shit, but

I’m finding it hard to swallow. . . . My card lies on the table, ignored next to an

orchid in a blue glass vase. Gently I pick it up and slip it, folded, back into my

wallet. . . .

I’m still tranced out on Montgomery’s card—the classy coloring, the thick-

ness, the lettering, the print—and I suddenly raise a fist as to strike out at Craig

and scream, my voice booming. (44–46)

Patrick, unlike most successful 1980s businesspeople, indulges in murder as

an extracurricular activity. Although American Psycho is littered with descrip-

tions of Patrick’s favorite hobby, what interests me here are not the murders

themselves but the ways in which the text includes the defilement of numer-

ous women among its other lists. Their lack of importance in the overall

narrative demonstrates how the killings are simply another of Patrick’s in-

terests, much like his favorite music, and just one more diversion from the

banality of life in the fast lane. In the following passage, Patrick discusses the

rape and torture of one of his victims: “She’s barely gained consciousness

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

144 our cannibals, ourselves

and when she sees me, standing over her, naked, I can imagine that my vir-

tual absence of humanity fills her with mind-bending horror. I’ve situated

the body in front of the new Toshiba television set and in the VCR is an old

tape and appearing on the screen is the last girl I filmed. I’m wearing a Jo-

seph Abboud suit, a tie by Paul Stuart, shoes by J. Crew, a vest by someone

Italian and I’m kneeling on the floor beside a corpse, eating the girl’s brain,

gobbling it down, spreading Grey Poupon over hunks of the pink, fleshy

meat” (328). Ironically, Patrick’s description of his cannibalization of a hu-

man brain lends new significance to a Toronto dry cleaner’s latest slogan:

“Poupon on your Prada?” (Canadian 86).

Corporate Cannibalism

If Bateman’s consumerism (in all its aspects) is a sign of the times, the novel

does note, in its final line, “THIS IS NOT AN EXIT” (399). But what is? In

our postmodern world, aspects of cannibalism have begun to underpin many

aspects of everyday life. Some theorists argue that anthropophagy is the es-

sential metaphor for late capitalism (Bartolovich, Forbes, Morris). Indeed,

the very act of consumption (especially in relation to shopping) has taken

on anthropophagic overtones. In Gone Shopping, Ann Satterthwaite notes,

“‘Cannibalization,’ or just trying to kill your competitor, is rampant in the

[retail] world” (72). Concomitantly, Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferris al-

lude in On Fashion to a “cannibalization of style” (15) that proliferates among

clothing designers. Furthermore, bell hooks suggests that the Western desire

for all things ethnic is a form of “eating the other,” and, along similar lines,

in Cannibal Culture Deborah Root attempts “to construct a topography of

the West’s will to aestheticize and consume cultural difference. The various

sites in which this occurs are organized around the central image of the leg-

endary cannibal monster who consumes and consumes, only to become

hungrier and more destructive” (xiii).

By the 1990s, the overt flaunting of retail goods had lost much of the ap-

peal it held in the 1980s, chronicled in American Psycho. But the “legendary

cannibal monster” of whom Root speaks makes an appearance in an award-

winning box-office smash. Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs

(1990), paradoxically released in “the year of the woman,” interweaves sev-

eral of the themes discussed in this chapter: Difference is literally consumed,

fashion is reconstructed, and the cannibal, instead of appearing as a savage,

becomes an ultra-sophisticated being, with impeccable taste and a refined

sensibility, whose desires are never satiated.

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 145

Lecter’s Lectures

In the film version of Silence of the Lambs (as well as the book on which it is

based) Hannibal “the Cannibal” Lecter acts as an advisor to the FBI, which is

searching for rampant serial killer Buffalo Bill (so called because he “skins his

humps”). By portraying one killer who eats his victims and another who hunts

and skins them, Silence fuses two forms of flesh-eating. Moreover, given Lect-

er’s ambiguous sexuality and Bill’s craving to become a woman (although,

Lecter warns, Bill is not really a transsexual; he only thinks he is), nonnorma-

tive sexuality is again pinpointed as a site of instability and danger.

The FBI agent assigned to Lecter, Clarice Starling, has had her own prob-

lems with flesh-eating. Clarice, who is acquiring a sense of belonging through

her performance at the FBI, is still vulnerable: She is a trainee, she is young,

she is female. Lecter’s psychiatrist, Dr. Chilton, remarks that Clarice will

appeal to Lecter (“Are you ever his taste!”), the appeal she holds seems to stem

from her vulnerability. Lecter probes Clarice about her childhood, which she

spent with relatives who ran an abattoir. The title of both movie and film are

culled from her efforts to silence the screaming of the lambs as they were led

off to slaughter. Clarice’s past interests Lecter, who trades information for

insights into her psyche. As the reservoir of information about Buffalo Bill’s

past, Lecter holds the key to Bill’s identity and modus operandi; he hints to

Clarice that, unable to qualify for a sex-change operation, Bill has decided

(again, like Gein) to sew himself a woman suit, using the flesh of his victims.

Fashion plays a prominent role in the cinematic conclusion, for, ultimately,

Clarice “pieces together” Bill’s identity through the clues Lecter has offered

her. Repeating like a mantra Lecter’s words—“How do we first start to cov-

et? We covet what we see every day.”—she visits the first victim’s home. When

her gaze is arrested by nude pictures of the young woman, she equates the

female body objectified by the camera’s gaze with the gaze of the killer and

with the objectified female form of a tailor’s dummy. She then perceives a

correlation between sewing patterns and the patterns of the wounds she has

seen on the victims, reading domestic clues to arrive at the insight that Buf-

falo Bill is using women’s skins as material with which to sew himself a new

body. For him, the victims’ bodies are the materials of his own sexual trans-

formation, and in this way, to borrow hooks’s terms, he “eats the other.”

As a result of Clarice’s efforts, Bill is apprehended, but halfway through

the narrative, Lecter manages to escape his imprisonment. In the final scenes,

he is pictured walking down a tropical street that is thronged with people of

color. The placement of the white Lecter in a white suit amid a sea of non-

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

146 our cannibals, ourselves

white faces spotlights him as the new savage, particularly because he is stalk-

ing another victim—his former psychiatrist, Dr. Chilton—whom he will

consume, and thus consume the position Chilton used to hold over him.

Incorporations

As readers learn in Hannibal, Lecter’s penchant for flesh stems largely from

the Nazis’ rape and murder of his sister. Hence, from a psychoanalytic per-

spective, his suppressed desires for her and his failure to cope with her loss

parallel, to some degree, Penelope Deutscher’s analysis of mourning in

“Mourning the Other, Cultural Cannibalism, and the Politics of Friendship

(Jacques Derrida and Luce Irigaray).” Deutscher’s argument offers some

insight into Lecter’s situation when she notes, quoting Derrida, that unsuc-

cessful mourning occurs when the “incorporated dead . . . continues to lodge

there like something other and to ventrilocate through the ‘living. . . . I lose

a loved one, I fail to do what Freud calls the normal work of mourning, with

the result that the dead person continues to inhabit me, but as a stranger’”

(162). Deutscher contends that in Derrida’s discussion, “the term ‘incorpo-

rated’ signal[s] precisely that one has failed to digest or assimilate it totally”

(162). If Lecter’s love for flesh stems from his inability to “swallow” his sis-

ter’s loss (a failed mourning), “‘normal’ or ‘successful’ mourning” occurs

when “the dead object is ‘taken back inside the self, digested, assimilated’”

(162). As Deutscher quotes Derrida, “‘The dead other . . . is taken into me: I

kill it and remember it. . . . I interiorise it totally and it is no longer other’”

(163). For Deutscher, “cannibalism, then, (digestion of the other) would ap-

pear to be an ethical miscarriage” (163).

Indeed, successful mourning (which Deutscher pace Derrida contends is

impossible) involves the consumption of the other within the self. Deutscher

foregrounds the cannibalistic movements of Derrida’s assertions and insists,

“It is the interiorizing normal work of mourning that Derrida marks as the

taking with me of the dead other, total interiorization, described with met-

aphors of digestion and cannibalism: ‘I kill it . . . and it is no longer other’

(The Ear of the Other 58), through the taking within oneself of ‘the body and

voice of the other, the other’s visage and person, ideally and quasi-literally

devouring them’ (Mémoires 34). By contrast, in encryptment there is an en-

veloping within one’s boundaries of an other that remains undigested, like

Jonah to the whale” (163). In other words, and in accord with de Certeau’s

theory of shifting boundaries, the Other must become a part of the self in

order for successful mourning to occur. One must consume the Other, be-

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 147

come the Other, assimilate the Other, and the inability to do so leaves the

mourner haunted by the dead.

Ne Plus Ultra

David Madsen’s Confessions of a Flesh-Eater provides a dramatization of

Deutscher’s reading of Derrida. In it, the absorption of the Other, as a result

of an obsession with the mother, illustrates a failed mourning—and its (lit-

eral) cannibalistic results.

Madsen’s text, published in 1997, follows the life of a flesh-lover—in all

senses of that term. The protagonist, Orlando Crispe, begins life knowing one

thing: “My first craving was for flesh” (10). This first craving is manifested

in a compulsion for the maternal breast, but when Orlando loses his moth-

er at an early age, he sublimates his love for her into his passion for meat. He

finds an outlet for his compulsion in cooking and becomes a chef, leaving

him free to fondle flesh whenever he likes:

The cold-store was . . . the tabernacle before which I made my own private de-

votions, for there the great carcasses hung—alluring and suaveolent, raw and

richly sweaty; sometimes I stood for five or ten minutes at a time, perfectly mo-

tionless, my face pressed against the smooth marble-veined flesh, my nostrils

caressed by the perfume of coagulated blood, rapt in ecstatic dulia. And I con-

templated the phantasms that projected themselves upon the silkscreen of my

ravished imagination. My penis trembled. On these occasions I was in a state of

intense aching, of bitter-sweet longing for my apprenticeship in the art and sci-

ence of self-expression in flesh to commence; running the tip of my tongue slowly

and salaciously across the fibrous plane of a wine-dark flank, I craved the sweet-

ness of that communion between creator and primal matter which only those

who burn with the flame of genius can truly know or comprehend. (34)

Orlando eventually opens his own restaurant in which he can experiment

to his heart’s content. And as he experiments, he discovers that human flesh is

the ne plus ultra. Soon, both friends and enemies fall prey to Orlando’s knife:

Cutting up and disposing of Heinrich Hervé’s massive corpse was not the

difficult task I at first imagined it would be; in fact, in the end, it proved to be

rather easy. Since both Heinrich’s appearance and character were exceptional-

ly pig-like, I followed the joint markings for that particular beast, using a Rev-

lon Sunset Glow lipstick to cover his pale, bloated body with the bright red lines

that would show me where I had to cut. The two really weren’t so very differ-

ent—head, loin, chump, leg, belly, it was all there—except that I had to make

do without the trotters, for even I blanched at the thought of Heinrich’s sev-

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

148 our cannibals, ourselves

ered hands and feet served up as Pieds de Porc Grillé, garnished with apple sauce

and gherkins. (171).

Orlando disposes of many bodies in this fashion, including those of his closest

relatives—“I ate my father” (174)—and his illicit activities go unnoticed until

he finds himself involved in the murder of a hostile food critic. But luck is

with Orlando, who evades the charges of murder levied against him and

moves to Geneva. There, he opens a new restaurant, Le Piat d’Argent, which

evolves into a widely acclaimed and exclusive club:

Flesh! I surround myself with it, I luxuriate in it, I shape it, mould it, dissect it,

transform and adore it! I never cease to develop my alchemical art—honing

and refining my techniques, constantly discovering new methods and means,

giving myself over unreservedly to its certainties and possibilities. . . .

If you are ever passing through Geneva, I invite you to try the gastronomic

delights of my restaurant—ask anyone, and they will tell you how to find it. But

be warned, if you intend to dine chez Orlando Crispe, you had better be a true

flesh-eater. (221–23)

Orlando’s memoirs are interlaced with various recipes (aiguillettes de cane-

tons au esprit de femme: “The breasts used to create my version of this dish were

taken from a lady well-known in certain circles for her lavish distribution of

sexual favours. . . . I specify duck as an excellent substitute” [222]) and the re-

ports of his prison psychiatrist, Enrico Balletti. Dr. Balletti is so horrified by

what he hears from his patient (whom he calls “the monster”) that he devel-

ops his own philosophy, in opposition to Orlando’s: “I have called my philos-

ophy ‘Sacrificialism’—an antidote to the murderous heresy of Absorptionism,

spewed forth by the monster. Life and death are met in deadly combat, as the

scriptures truly say! Mors et vita: for my speculations, agonizing as they have

been, concern themselves with life, while the monster—with his obscene meta-

physic—is none other than the Master of Death” (151). Dr. Balletti soon swears

off all meat and turns into a reluctant vegetarian: “We must cease to eat flesh.

We must cease to slaughter millions of innocent creatures for our own gastro-

nomic pleasure. . . . Have we so glutted ourselves on flesh—thick and blood-

ily crimson—that we have forgotten the delights of the gentle green children

of the soil?” (153). Eventually, he suffers from a complete nervous collapse (200),

his psychoanalytic frame unable to incorporate or absorb Orlando.

Cross-Global Transfers

Confessions of a Flesh-Eater offers an interiorized view of Western anthro-

pophagy, which, in my reading here, draws on theories of alterity. To shift

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 149

theoretical paradigms, I want to return to a postmodern shift to sliding

signifiers (as in the displacements of germ theory) because this text, along

with The Silence of the Lambs, Eating Raoul, and American Psycho, indicates

a firm acceptance that the cannibal is “here,” manifesting a twist on anthro-

pophagic movements of the early century wherein the culprits were “there”

and only threatening to come “here.” To compound matters, and as the con-

clusion of The Silence of the Lambs suggests, not only is the cannibal “here,”

he is now (once again) moving “there,” further destabilizing the boundaries

between “us” and “them,” as dramatized in Lecter’s final placement in the

tropics. This theme is picked up in millennial texts such as Ruth L. Ozeki’s

1998 debut novel My Year of Meats, which highlights Western anthropoph-

agy and its spread to other cultures.

My Year of Meats features Jane Takagi-Little, Ozeki’s Japanese American

protagonist, who subverts all Japanese American stereotypes: “I am just un-

der six feet myself. In Japan this makes me a freak. After living there for a

while, I simply gave up trying to fit in: I cut my hair short, dyed chunks of it

green. . . . It suited me. Polysexual, polyracial, perverse” (9). Jane is an un-

employed documentary filmmaker who takes a job in television to make ends

meet. She becomes the producer of a Japanese series called “My American

Wife,” which is sponsored by a multinational beef conglomerate, and dra-

matizes American cooking habits for Japanese women (in the hope that it

will inspire greater meat consumption).

Jane and her multicultural crew travel around the United States to scout

out “real” American housewives who will agree to appear on the program

and cook their favorite meat dishes. The more interviews Jane conducts,

however, the more disturbed she becomes by the impetus of the series: “This

was the heart and soul of My American Wife: recreating for Japanese house-

wives this spectacle of raw American abundance. . . . Locating our subjects

felt like a confidence game, really. I’d inveigle a nice woman with her civic

duty to promote American meat abroad and thereby help rectify the trade

imbalance with Japan” (35). Jane’s real problem is that she grows fond of her

subjects and dislikes using them in the program (where, unbeknownst to the

Americans, they are viewed with great amusement by the Japanese).

Soon her buried documentary instincts begin to emerge, and she starts to

film episodes for “My American Wife” that focus on those whom she per-

ceives as the “real” Americans—the “other” Americans who rarely garner TV

time. In one segment, which comes to be labeled “the Lesbian Show,” Jane

interviews a female interracial couple who are also vegetarians, a fact that does

not go down well with her sponsors (176–80). Nonetheless, as Jane and her

crew get closer to their interviewees, they also indirectly influence cross-global

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

150 our cannibals, ourselves

transfers. In one instance, one of Jane’s crew members alerts a Southern farm-

er to the special qualities of kudzu: “Back at the house, he [Suzuki] showed

Vern how to turn them into starch, then how to use the starch to thicken

sauces and batters. He made a salad with the shoots and the flowers, and even

a hangover medicine that resembled milk of magnesia. Vern was astounded.

He’d never thought of the plant as anything but an invasive weed” (76).

Such transfers go both ways, however, as is apparent when Jane, still try-

ing to remain faithful to her ethics as a documentarian, decides to produce

a segment on a family that owns a feedlot and a slaughterhouse. In doing so,

she walks a tightrope, for “If the feedlot is anything like the ones I’ve been

reading about, there should be plenty of opportunity to shoot some pretty

horrifying material. And the slaughterhouse—I have high hopes for that.

What am I hoping to accomplish? Am I trying to sabotage this program? I

need this job. I can’t afford to get fired now. On the other hand, I can’t con-

tinue making the kind of programs Ueno wants, either. What am I supposed

to do?” (210). Jane films the feedlot and the slaughterhouse, including its

practice of “‘recycling cattle right back into cattle.’ ‘That’s cannibalism!’ . . .

‘They ain’t humans’” (258). Not surprisingly, as soon as the sponsors view

this footage, Jane is fired from “My American Wife.” Yet after a period of

depression, she reemerges undaunted and decides to make a video about what

she has discovered on the farm: “Editing my video was hard. It was not a TV

show: just the feedlot with its twenty thousand head of cattle, and Gale talk-

ing about food and drug technologies; the drugs in the feedmill; . . . the cow-

boys with their hypodermic needles and the aborted calf fetus; the slaugh-

terhouse, and the vat of hormone-contaminated livers, oozing viscous yellow.

. . . I still couldn’t imagine what I would do with the tape, once I’d finished

editing it. I mean, who would want to see it?” (335).

Despite Jane’s misgivings, the video, which clearly documents the toxici-

ty of mass-produced meat, generates a flurry of interest. In shooting this

particular feedlot, Jane has inadvertently exposed an illegal operation wherein

the cows are injected with a synthetic hormone, diethylstilbestrol, once used

as a pregnancy drug in women and now used as a growth stimulant in cat-

tle. The hormone has been outlawed in the United States because it produces

abortions, ovarian cysts, and ultimately cancer (which can be passed from

mother to child) but is still available and is used at this slaughterhouse in meat

processed for home and abroad. Consequently, another cross-global trans-

fer takes place wherein Western flesh-eating practices begin to infect the earth

and generate international conflicts: The “interview about cattle feed, espe-

cially the practice of feeding cow parts back to cattle, stirred up a wave of

media concern about bovine spongiform encephalopathy and its human

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 151

equivalent, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. It had first made the news back in 1987,

when the disease was identified in England and given the media-sexy name

‘mad cow.’ Yet despite awareness of the dangers, the practice of feeding offal

to ruminants continued in America. The Japanese didn’t like this” (358).

Ultimately, when news of the local practice breaks, the global uproar forces

an investigation into the mass production of beef. In My Year of Meats, then,

media (be it novel, television, or video) bring worldwide pressure to bear on

Western production measures that threaten to taint other societies. Indeed,

the cultural anxieties apparent in Ozeki’s novel are especially portentous at

the turn of the century, for as Elaine Showalter argues in both Sexual Anar-

chy and Hystories, centurial changes are prone to divergent forms of cultur-

al hysteria.

Millennial Musings

As the world prepared for the coming millennium, Jim Wright resigned his

post as speaker of the House in 1997, decrying the “‘mindless cannibalism’

he said was consuming Congress” (Verhovek). Shortly thereafter, fears of the

potential damage that might be caused by the change from 1999 to 2000 in

computer systems swept throughout the world. Anticipating computer fail-

ures, which could lead to international breakdowns (via stock markets, bank-

ing codes, flight patterns, and other systems), countries still devoted them-

selves to celebrations of international unity. On New Year’s Eve, 1999,

television offered spectators a chance to celebrate the coming millennium

around the globe; CNN broadcast live coverage of the festivities in a remote

village in Kenya, the enormous fireworks display in London, and the multi-

media extravaganza in Washington, D.C. As the Eiffel Tower danced, audi-

ences cheered.

The global celebration provided a spectacular manifestation of the changes

that took place in the twentieth century, in itself illustrating how the world

has become more “known” (via mass media and international travel) and

thus more assimilated into the cultural consciousness. Former boundaries

between the familiar and the strange have become porous, allowing bleed-

ings and leakages between the two. As a result of cultural familiarity, divi-

sions between “us” and “them” no longer hold, leaving the Other to slip and

slide, without a firm base in the “strange” it previously occupied.

Contiguously, the losses suffered over the past hundred years—through

genocide, changes in global power, and even divergent ways of life—may also

mean that the world is in mourning, not having completely digested and

incorporated the centurial losses, as Deutscher argues. The dawn of a new

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

152 our cannibals, ourselves

century leaves people poised to move on but perhaps unable to do so, still

caught in the last century’s cultural perceptions and social paradigms. Many

of the ensuing anxieties are expressed anthropophagically as cannibalism

becomes a major cultural metaphor in everyday life. From serial killers to

disease narratives to organ transplants to the spread of mad cow disease,

flesh-eating (in one form or another) pervades twentieth- and twenty-first-

century existence. Thus, although cannibal tales are certainly not new, their

transformation into household phenomena is unique to this era. Following

a postmodern displacement paradigm, flesh-eating has shifted from “there”

to “here,” and although one might speculate endlessly as to its cause, the effect

is clear. To cite Dr. Henry Lee’s testimony at the O. J. Simpson trial, “Some-

thing wrong here.”

To return to de Certeau’s contentions, with which I began this study, the

twentieth century has witnessed a redistribution of cultural space that gives

rise to divergent representations of the cannibal. Some of these representa-

tions are recirculated versions of older narratives. For example, I am writing

this conclusion days after Toronto mayor Mel Lastman announced, just be-

fore his trip to Africa to recruit supporters for Toronto’s 2008 Olympic bid,

“Why the hell would I want to go to a place like Mombasa? I just see myself

in a pot of boiling water with all these natives dancing around me” (“Tor-

onto”). Unlike Lastman’s reinvocation of a nineteenth-century construction,

other representations of the cannibal are innovative and used to describe

scientific and technological developments in terms familiar to contemporary

audiences. All too often, cannibalism is referenced as a means of explaining

virus mutations, cyberspace innovations, and patterns of consumption. The

cannibal seems to be the signifier of both familiarity and strangeness, a double

denotation that appears to reinforce its recurrent usage. Perhaps this is why

it crops up over and over again in disparate venues. As the ultimate indica-

tor of familiarity and strangeness, it is the one representation that is both

abhorrent and easily recognizable, a means of targeting practices that are

strange and making them familiar—an “Othering” stratagem that, while it

shifts and mutates (constantly destabilizing the binary it seeks to maintain),

still retains its efficacy in distancing as loathsome, as well as rendering com-

monplace, new threats to the home space. And it continues over into the new

epoch, if in unexpected ways.

Cannibalism and Everyday Life

While Camel cigarettes ran an advertisement in major magazines featuring

a group of men in a hot tub–stew pot tended by women (with cannibalism

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cannibal Culture 153

seemingly operating as a trope for gender anxieties), Thomas Harris’s Han-

nibal was released in theaters in 2001. Audiences watched as Hannibal Lect-

er sliced brain tissue from a still-conscious FBI agent, braised the slices, and

presented the ensuing “sweetbreads” to Clarice as a token of his love and

esteem. Perhaps not surprisingly, on February 12, 2002, Canada’s The National

Post reported on a new chocolate development for Valentine’s Day: “Medi-

cal supply companies offer an array of anatomically correct, truly heart-

shaped products” (B9), providing a twist on the old adage “eat your heart

out.” In turn, and in the wake of the millennial celebrations, CBS broadcast

a TV replacement show that suddenly captured media headlines.

“Survivor,” a docudrama–cum–game show, riveted TV audiences, who,

week after week, followed a group of Westerners “stranded” on a tropical

island, trying to outlast their companions long enough to win the million-

dollar prize. Viewers could also visit Web sites that enabled them to watch

the survivors throughout the day, and, once a week, a summary program was

broadcast on primetime TV. Its ratings suggested that the audience was en-

thralled with the survivors’ searches for food (eating bugs and snakes, among

other island delicacies) and their attempts to navigate for political promi-

nence among their peers and to manipulate their own “survival” on the pro-

gram.

One particular Web site devoted to the program, called “Survivor Sucks,”4

highlighted the underlying movement of the series as it cast its update of the

survivors’ “demise” in cannibalistic terms. As one person was ushered off the

island each week, the site described him or her as having been “cannibalized.”

For example, in the first episode Sonja was voted off the island, and the site

concluded, “Voting to eat Sonja was probably a bad idea, as we assume, due

to her age and frail condition, that she was a bit tough and chewy, and didn’t

provide much sustenance. A rat would probably have been a better meal than

Sonja. SS thinks that the group should have chosen Richard. We’re sure he’s

tender and juicy.” In the seventh week, the site noted how the remaining

survivors could “chow down on Gretchen’s hide. But as she has a good bit

of meat on her bones, their sorrow shouldn’t last long.” It later turned to

Gervase, the only African American man, and described him as “thin and

lean, but all meat. This should provide enough energy to tide the group over

until the next bloodletting.” “Survivor Sucks” waxed enthusiastic in the

twelfth week, when its excitement over the nearing final episode pervaded

its assessment of Sean’s “demise”: “And what about the meal—how did Sean

taste? We hate to say it, but let’s just hope that they gutted him well before

digging in. Remember: this is the guy who only goes to the bathroom once

every two weeks. Maybe they served him up as a pu-pu platter. So what’s next?

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

154 our cannibals, ourselves

The moment we’ve all been waiting for is just around the corner: The Alli-

ance will be forced to cannibalize itself.” The Alliance was “forced to canni-

balize itself” and left Richard, the gay white man, as the sole survivor and the

million-dollar winner. That week, the site celebrated Richard’s win and his

savvy game-playing: “Who would have thought way back at the beginning

of the season that the ‘Fat Naked Fag’ would take it in the end? (Quite a few

of us, actually. . . .) But seriously, we happily, almost gleefully, admit that

Richard played ‘The Game’ far, far better than the others. His duplicity, his

arrogance, his scheming, his alliance building, his pouting in the tree dur-

ing the first episode, his running around naked, his crowing over his fishing

skills, and his lying to Jeff were all fascinating to watch.” Ruefully, “Survivor

Sucks” acknowledged that, “like the other 15 castaways, we would have wound

up Rich’s dinner.” “Survivor,” it seems, taught both game players and view-

ers alike how to cannibalize and how to recognize a great (gay) cannibal in

action.

Importantly, “Survivor” illustrated how Western viewers no longer had to

look to “darkest Africa” or the jungles of Borneo for flesh-eaters because

“cannibals,” just like “us,” were stalking primetime TV. Indeed, the incred-

ible popularity of the program indicated all too well how “them” had become

“us” in a pattern that (appeared to) set the stage for broadcast TV in the new

millennium. “Survivor Outback” (aired in the 2001 winter season) main-

tained this trend, which continued in “Survivor Africa” (fall 2002) and “Sur-

vivor Marquesas” (spring 2002, wherein cannibalism, given the history of the

island, was front and center). Consequently, if we are all cannibals who can

recognize and honor the “grand cannibal,” then the globalization celebrat-

ed on December 31, 1999, is complete in that cannibalism has come full cir-

cle: “We” have become “them” in the twenty-first century.

This content downloaded from

128.122.149.92 on Sat, 13 Nov 2021 23:27:44 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and ArtFrom EverandTrickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Health Certificate For US Pet TravelDocument1 pageHealth Certificate For US Pet TravelPetRelocation.comNo ratings yet

- Teach Yourself AbdomenDocument35 pagesTeach Yourself AbdomenSambili Tonny100% (4)

- ABMLI Sample Questions 000Document7 pagesABMLI Sample Questions 000samy100% (1)

- The Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of ScienceFrom EverandThe Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (47)

- Realm of Shadows 1940sDocument212 pagesRealm of Shadows 1940sNestor NovoaNo ratings yet

- Realm of Shadows (1940s)Document212 pagesRealm of Shadows (1940s)eris555100% (9)

- The Sticky SublimeDocument17 pagesThe Sticky SublimeHarriet SalemNo ratings yet

- Wide Open Fear: Collected Southern Dark Columns: Writer Chaps, #8From EverandWide Open Fear: Collected Southern Dark Columns: Writer Chaps, #8No ratings yet

- Behind the Slickrock Curtain: A Project Petrichor Environmental ThrillerFrom EverandBehind the Slickrock Curtain: A Project Petrichor Environmental ThrillerNo ratings yet

- The Age of Dystopia One Genre, Our Fears and Our Future by Louisa MacKay DemerjianDocument180 pagesThe Age of Dystopia One Genre, Our Fears and Our Future by Louisa MacKay DemerjianKapil Bhatt100% (1)

- When the Rooster Crows at Midnight: The Mallory Shane Witch Detective SeriesFrom EverandWhen the Rooster Crows at Midnight: The Mallory Shane Witch Detective SeriesNo ratings yet

- Back Roads Literary Review Scary Short Story Anthology - Fall 2023From EverandBack Roads Literary Review Scary Short Story Anthology - Fall 2023Michael D Van NattaNo ratings yet

- Wonder and Glory Forever: Awe-Inspiring Lovecraftian FictionFrom EverandWonder and Glory Forever: Awe-Inspiring Lovecraftian FictionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- PROUD GODS AND COMMODORES Volume II: Selected Poetry and Epic TalesFrom EverandPROUD GODS AND COMMODORES Volume II: Selected Poetry and Epic TalesNo ratings yet

- The2ndhand #30Document2 pagesThe2ndhand #30Todd DillsNo ratings yet

- WTW Serial 12Document9 pagesWTW Serial 12Filip MarinovichNo ratings yet

- El Seno Escondido Nodrizas y Nanas Como Agentes Maravillosos en La Novela Latinoamericana de La Segunda Mitad Del Siglo VeinteDocument317 pagesEl Seno Escondido Nodrizas y Nanas Como Agentes Maravillosos en La Novela Latinoamericana de La Segunda Mitad Del Siglo VeinteycescuderoNo ratings yet

- A Piece of Stri WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesA Piece of Stri WPS OfficeStephanie BanzuelaNo ratings yet

- "Deconstructing Psycho Killer Clowns" (Chapter, THE PYROTECHNIC INSANITARIUM, Mark Dery)Document27 pages"Deconstructing Psycho Killer Clowns" (Chapter, THE PYROTECHNIC INSANITARIUM, Mark Dery)Mark Dery100% (3)

- Article 2Document15 pagesArticle 2Arsalan Siddiqui MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Mortification: Writers’ Stories of their Public ShameFrom EverandMortification: Writers’ Stories of their Public ShameRobin RobertsonRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (42)

- A DISTURBING NOVEL BY LAURA SOLOMON Featured in in James Watson's Monthly Blog On Writing, Art, Culture, Film and Politics (No.42, September 2013)Document8 pagesA DISTURBING NOVEL BY LAURA SOLOMON Featured in in James Watson's Monthly Blog On Writing, Art, Culture, Film and Politics (No.42, September 2013)James WatsonNo ratings yet

- The Pit of The NamelessDocument6 pagesThe Pit of The NamelessEssenceNo ratings yet

- Molly and the Bandit: Or the Disappearance of the Celebrated Stagecoach Robber Black Bart SolvedFrom EverandMolly and the Bandit: Or the Disappearance of the Celebrated Stagecoach Robber Black Bart SolvedNo ratings yet

- Back Roads Literary Review Short Story Anthology - Spring 2024From EverandBack Roads Literary Review Short Story Anthology - Spring 2024No ratings yet

- The Yarn Spinner: A Crossroads Cafe Short StoryFrom EverandThe Yarn Spinner: A Crossroads Cafe Short StoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- LAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human Body - BS PSYCH 1 B 1Document10 pagesLAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human Body - BS PSYCH 1 B 1Louise BarrientosNo ratings yet

- STCatalog-2015-Spring Beef 2015-02-19 ReducedDocument32 pagesSTCatalog-2015-Spring Beef 2015-02-19 ReducedcrcarbonelldNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Milk Quality TestsDocument12 pagesGuidelines For Milk Quality TestsOsman Aita100% (1)

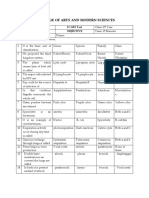

- Bagh College of Arts and Modern Sciences: 1 GST Test ObjectiveDocument2 pagesBagh College of Arts and Modern Sciences: 1 GST Test ObjectiveAbdul Waheed KhawajaNo ratings yet

- I. Topic: Pertussis II. ObjectivesDocument7 pagesI. Topic: Pertussis II. ObjectivesKaren PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Brochure XT-2000i and XT-1800i MKT-10-1136Document8 pagesBrochure XT-2000i and XT-1800i MKT-10-1136Cinthia Lizaraso VelapatiñoNo ratings yet

- Pernicious Anemia: BSMT 3D Group 1 Paniza, Erika Joy Villanueva, Andrewarnold Yandan, CharisDocument53 pagesPernicious Anemia: BSMT 3D Group 1 Paniza, Erika Joy Villanueva, Andrewarnold Yandan, CharisAndrew Arnold David VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- FCE CvičeníDocument8 pagesFCE CvičeníLucinkaNo ratings yet

- Nervous System: Mir Saleem, MD, MSDocument32 pagesNervous System: Mir Saleem, MD, MSNiyanthesh ReddyNo ratings yet

- Frog Dissection - Lab NotesDocument3 pagesFrog Dissection - Lab NotesShaniahNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Paediatric Dentistry: Lola Adewale MBCHB DCH FrcaDocument8 pagesAnaesthesia For Paediatric Dentistry: Lola Adewale MBCHB DCH FrcaJavier Farias VeraNo ratings yet

- Animal Rights - A Social Issue By: Mahima Bajpai V SemesterDocument20 pagesAnimal Rights - A Social Issue By: Mahima Bajpai V SemesterMahiema A BaajpaiNo ratings yet

- Cues/Needs Nursing Diagnosis Rationale Goals and Objectives Nursing Interventions Rationale Evaluation Subjective: - Change Position ofDocument6 pagesCues/Needs Nursing Diagnosis Rationale Goals and Objectives Nursing Interventions Rationale Evaluation Subjective: - Change Position ofWik Wik PantuaNo ratings yet

- Normal Anatomy and Physiology of Female PelvisDocument58 pagesNormal Anatomy and Physiology of Female PelvisVic RobovskiNo ratings yet

- Imaging PadaDocument77 pagesImaging PadaNaja HasnandaNo ratings yet

- Era Pelangi Form 2 ScienceDocument12 pagesEra Pelangi Form 2 ScienceSaya MenangNo ratings yet

- Rhabdo VirusDocument13 pagesRhabdo VirusSarah PavuNo ratings yet

- Neutral Zone Impression TechniqueDocument2 pagesNeutral Zone Impression Techniqueizeldien5870100% (2)

- Biology ReviewDocument197 pagesBiology ReviewEden Lucas Ginez PitpitanNo ratings yet

- Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine Answers For ExamDocument94 pagesAnesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine Answers For Exammichal ben meronNo ratings yet

- Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Infection in Adult PatientDocument10 pagesVentriculoperitoneal Shunt Infection in Adult PatientYhafapCezNo ratings yet

- UConn Prosthodontics Clinic Manual 12-13Document69 pagesUConn Prosthodontics Clinic Manual 12-13lippincott2011No ratings yet

- Common Reproductive Issues Instructor VersionDocument13 pagesCommon Reproductive Issues Instructor VersionDanielle DiorioNo ratings yet

- Pleural DiseasesDocument4 pagesPleural DiseasesJennifer DayNo ratings yet

- Properties of Cardiac Muscle PDFDocument38 pagesProperties of Cardiac Muscle PDFZaid RazaliNo ratings yet

- Danger Signs in NewbornDocument8 pagesDanger Signs in NewbornPrabhu MagudeeswaranNo ratings yet

- Raising RabbitsDocument86 pagesRaising RabbitsYousef Al-KhattabNo ratings yet