Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Legal Status of the Korean War

Uploaded by

SubhoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Legal Status of the Korean War

Uploaded by

SubhoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Nature of the 'War' in Korea

Author(s): L. C. Green

Source: The International Law Quarterly , Oct., 1951, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Oct., 1951), pp. 462-

468

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute of

International and Comparative Law

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/763249

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The International Law Quarterly

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NATURE OF THE 'WAR' IN KOREA

IN June, 1951, when the Minister of Local Governm

dismissed Mrs. Monica Felton from her position as c

Stevenage Development Corporation after her visit

as a member of a Commission sent to that country

International Democratic Federation,' it seemed

believed in Great Britain that this was the first occasion on which it

was necessary to consider the nature of the hostilities in Korea in

order to ascertain whether or not Mrs. Felton could be prosecuted

for treason. In fact, a similar problem had arisen two months

earlier. On April 12 the Press Association issued a letter 2 that

had been sent by the Minister of Defence to Mr. Raymond

Blackburn, M.P. In March, Mr. Blackburn had drawn attention

to certain matters appearing in the Daily Worker in connection with

the Korean war, and the Minister undertook to bring the question

to the attention of the Attorney-General. In his letter the Minister

said that the Attorney-General was 'well aware of the undesirable

activities of the Daily Worker . . ., some of which have every

appearance of coming within the definition of treasonable offences.

This does, of course, turn to some extent on the question whether or

not we are at war with China '. The Minister made no attempt to

answer this question, but said 'it seems likely that from a legal

point of view the state of hostilities between China and ourselves

is sufficient to bring the act of " giving aid and comfort " to the

Chinese within the definition of treason. The difficulty about

instituting a prosecution, however, is that no other charge than that

of treason would be possible, and that the only penalty for treason

is death '. In view of this, it was decided that no action should be

taken against the Daily Worker, just as in April the Director of

Public Prosecutions advised that no action be taken against

Mrs. Felton.

The problem of whether or not there is a war, in the technica

sense of the word, being fought in Korea has also arisen in the

United States. There, however, the matter was dealt with by legis-

lation and not administratively. An American soldier who had

returned from active service in Korea needed an operation, and

1 The report of this Commission alleging atrocities against the United Nations

and United States forces in Korea is published in the Los Angeles Korean

Independence, August 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 1951.

2 This letter is printed in The Times, April 13, 1951.

462

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OCT. 1951] The Nature of the ' War' in Korea 463

applied for admission to the Veterans' Administration hospital

Tucson, Arizona. He was denied admission, it having been poin

out by the manager of the hospital that the United States is t

nically not at war in Korea, and that a Korean ex-service man

the same status as a soldier discharged from the army in peace t

Immediately this incident became known Congress, at the reque

President Truman, passed legislation putting Korean ex-service

in the same position as ex-service men of both world wars.3

We are not here concerned with the application of the Engl

law of treason, or with other questions of municipal law. O

problem relates to the nature of the hostilities themselves, an

suffices for our purpose to accept the comment of the Attorn

General in September, 1950, when dealing with a question rela

to the presence of a Daily Worker correspondent with the No

Korean forces. On that occasion, Sir Hartley Shawcross pointed

that although the Korean war raised complicated questions of in

national and municipal law, there was no doubt that the law of

treason was applicable.4

The problem with which we are concerned was considered by

the Australian courts during 1950 and 1951. On April 6, 1951, only

six days before the publication of the Minister of Defence's letter,

the appeal of the publisher of the Australian communist newspaper

The Tribune, against a sentence of nine months for sedition, was

dismissed.5

The Crown had alleged that articles printed in The Tribune

dealing with the Korean war were intended to promote feelings of

ill-will and hostility between different classes of His Majesty's

subjects so as to endanger the peace, order and good govern-

ment of the Commonwealth, and to promote disaffection against

the Government and Parliament. The article that was most strongly

objected to appeared on July 12, 1950, and was occasioned by the

seamen's strike of that month. Under banner headlines reading

' Seamen's Patriotic Lead-Stop War in Korea ', the newspaper

declared ' Not a man, not a ship, not a plane, not a gun for war on

Colonial liberation movements in Asia '. In August a Summary

Court sentenced William Fardon Burns, the newspaper's publisher,

to nine months for sedition, and his appeal against this verdict came

before Judge Berne in Sydney on November 13 and 14.6

Judge Berne was seriously concerned with the nature of the

hostilities in Korea, and for that matter in Malaya, for he said : 'It

seems to me that the articles could not possibly be seditious . . . if

3 New York Herald Tribune, May 11, 1951.

4 The Times, September 20, 1950.

5 Sydney Morning Herald, April 7, 1951.

6 Sydney Morning Herald, November 14-5, 1950.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

464 The International Law Quarterly [VOL. 4

this is an illegal war '. In order to prove the legality of t

war and of the participation of Australian troops therei

cuting counsel referred to Australia's obligations under th

of the United Nations. This argument, apparently, did n

to Judge Berne who took an exceedingly narrow view of t

of the Australian Charter of the United Nations Act.' This statute

was described as ' An Act to approve the Charter of the United

Nations ', and the learned judge stated: ' The view I take is that

the United Nations Charter is only an agreement. . . . The Crown

did not ratify it. It said it approved of the agreement. It would

have been very easy for the Crown to have said that the Charter

was approved and ratified. . . . The agreement did not supersede

the Constitution and any assistance given in Korea must be justified

by law'. There is no need to consider whether Judge Berne's inter-

pretation of this Act and of the nature of the Charter is correct or

not, for he immediately went on to say": 'The Commonwealth will

not tell me whether we are at war with Korea or not. I insist on

knowing that. . . . If what is going on in Korea is not a war, th

the newspapers are lying. I refuse to believe it is not a war. . ...

want to know why Commonwealth Ministers say we are at w

Only His Majesty could declare war '.

The learned judge seemed equally doubtful as to the nature of

the operations in Malaya. These he described as ' merely pol

action against terrorists. It is quite legal to use troops to bre

strikes and load ships. But I do not think it would be legal to qu

risings in other countries '.

The problem with which we are concerned was referred to th

Australian Foreign Office, whose replies to a number of questions put

to it were read in Court. The reading of these replies caused a mo

unpleasant scene in the court-room. At first Judge Berne refused

allow the Foreign Office statement to be read, and demanded a dir

answer, either positive or negative, to the question whether Australia

was at war with Korea. When the complete statement was read

there were mutual accusations of bad faith and inexactitudes

between the judge and leading counsel for the prosecutio

questions were supposed to have been taken from the tran

the proceedings, but of one question-relating to the 38th

Judge Berne said : ' If I asked that question as you have p

it a sinister construction could be placed on it '. Counsel

Commonwealth insisted that 'you definitely said it ', and

threatened to order him to leave the court if he continued to contra-

dict. Counsel refused to withdraw his statement and left. After

his departure junior Crown counsel refused to continue and Judg

7 Act No. 32 of 1945.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OCT. 1951] The Nature of the ' War' in Korea 465

Berne said he would inform the Attorney-General when he was r

to resume. During the dispute between judge and counsel,

Shand, for the Commonwealth, requested that a case be stated

include the question ' Whether his Honour's conduct of the tria

resulted in the respondent-the Commonwealth-being deprived

natural justice? '. On February 12, 1951, a writ of certiorari w

granted to the Commonwealth and a new judge instructed to

the appeal,8 and, as has already been pointed out, on April 6 t

appeal was dismissed.

What is important in the Burns Case is not the decision, nor

unseemly quarrels between judge and counsel. From the point

view of international law the most significant feature of the case w

the statement issued by the Foreign Office. This was as follow

' Q. Is Australia at war with North Korea ?

'A. The Government has sent land, sea and air forces to

Korea to assist in taking military measures in order to restore

international peace and security in Korea as provided in

Chapter 7 of the Charter of the United Nations. The Australian

forces are engaged in active hostilities and have suffered inten-

sive casualties. That Australia is at war de facto is clear.

Whether or not Australia is at war de jure depends on the

interpretation of the Charter as applied in the circumstances.

' Q. Is North Korea at war with Australia ?

' A. Answer as above.

' Q. What is the nature of the warlike operations at pr

north of the 38th Parallel ?

' A. The military operations have proceeded against the

38th Parallel against the resistance of North Korean forces,

and are now being carried on in the vicinity of the border

between Korea and Manchuria. A feature of these operations is

at present under consideration by the Security Council. The

Australian Government regards all the Korean operations as

having been conducted under the Security Council and in pur-

suance of the United Nations Charter.10

' Q. Is Australia at war with Malaya?

'A. No.

' Q. In both cases, has war been declared ?

'A. No declaration has been made in either case.

1 Radio Australia News (London), February 13, 1951

9 Sydney Morning Herald, November 15, 1950.

10o For a discussion of the activities of the Security Council in connection wit

Korean war, see the writer's ' Korea and the United Nations ', 4 World Aff

(New Series), 1950, p. 414.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

466 The International Law Quarterly [VOL. 4

'Q. What is the nature of the operations being car

in Malaya ?

'A. The Australian Government has sent air forces to assist

His Majesty's Government in the defence of Malaya in suppres-

sing armed insurgents conducting guerrilla warfare in that

country to the prejudice of the peace and safety of His Majesty's

subjects and territories.

' Q. On what authority does the Commonwealth rely for

sending troops to either of these places or the expending of

public money for equipping those troops ?

' A. The Commonwealth Parliament, having by the Charter

of the United Nations Act, 1945, approved the Charter, the

Government deposited on November 1, 1945, an instrument of

ratification, and the Charter thereupon became binding upon

the Commonwealth in international law. The Commonwealth

has acted in pursuance of the Charter and of the Defence Ac

the Naval Defence Act, and the Air Force Act, and under the

provision of appropriations made by Parliament.

' Q. What nations were present as required under Article 27

when the resolution was carried that North Korea was the

aggressor ?

' A. All members of the Security Council except the

U.S.S.R.x1

' Q. Has the Commonwealth ever recognised North Korea ?

' A. The Commonwealth has not recognised " The People's

Democratic Republic of Korea ".'

This statement makes it perfectly clear that in practice the

Commonwealth of Australia regards itself as at war with an

unrecognised entity known as 'The People's Republic of Korea'.

That being so, even Judge Berne agreed that the article in The

Tribune was seditious.

It is unnecessary to study in detail the differences between

de jure and a de facto war. The practical effects of both ar

virtually the same. Experience in the Korean war has mad

clear that the United Nations and its enemies regard themselve

at war, and have both declared their intention of conducting th

hostilities in accordance with the rules of war. All that need be

said is that a war, whatever be the strictly technical meaning of th

word, is being fought in Korea. This appears to be the attitude o

all the nations that are engaged, and from what has already bee

said this seems to be clearly the case with the United Kingdom an

the United States as well as Australia. Nevertheless, in the

11 The legality of this decision of the Security Council is examined in the writer's

article cited in n. 10 above, at pp. 427--8 and p. 432.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OCT. 1951] The Nature of the 'War' in Korea 467

Conimunist Party Dissolution Case (1951)12 each of the judges c

stituting the majority (Dixon, McTiernan, Williams, Webb, Fulla

and Kitto JJ.) pointed out that in October, 1950, the date of t

passing of the Communist Party Dissolution Act, Australia was

peace. This was important, because the validity of the Act depen

to a great extent on the exercise of the Commonwealth's defen

power. Not all the judges referred to Korea, although Dixon

McTiernan JJ. did so expressly. Dixon J. pointed out that

' Australian forces were involved in the hostilities in Korea, but

country was not of course upon a war footing, and, though

hostilities were treated as involving the country in a contributio

force, the situation bore little relation to one in which the applicati

of the defence power expands because the Executive Governme

has become responsible for the conduct of the war '. McTierna

expressed the situation even more simply: 'At the time the

came into force the Commonwealth was not engaged in any hostiliti

except in Korea. The state of affairs was peace not war '.

The Burns Case is not the first case in which a British court has

recognised the possibility of a de facto as distinct from a de jure

war. In Kawasaki Kisen Kabushiki Kaisha of Kobe v. Bantham

S.S. Co. [1939] 2 K.B. 544, the Foreign Office pointed out that it

was not prepared to say that a ' war ' then existed between China

and Japan, and stated that ' the attitude of His Majesty's Govern-

ment may not necessarily be conclusive on the question whether a

state of war exists within the meaning of the term " war " as used

in particular documents or statutes '. It will be recalled that the

Master of the Rolls held that, for the purposes of the charterparty in

issue before him, a war was in existence.

Where civil wars are concerned it is not uncommon to find the

hostilities being regarded as war de facto. As it was expressed by

the Supreme Court of the United States in The Prize Cases (1862

' A civil war is never declared, it becomes such by its accidents..

When the party in rebellion occupy and hold in a hostile manner

certain portion of territory, have declared their independence; . .

have organised armies; have commenced hostilities . . . , the wor

acknowledges them as belligerents, and the contest a war'."

Similarly, in Prats v. United States, decided under the Convention

of 1868, the United States-Mexican Mixed Claims Commission stated

that ' had Great Britain never recognised the Confederates as belli-

gerents at all, the consequences of the state of war as a fact to

Great Britain, as to all other neutral powers, would have been the

12 83 C.L.R. 1. The extracts from the judgment are reproduced from the galley

proof which has been made available through the courtesy of The Law Book Co.

of Australasia Pty. Ltd., the publishers of the Commonwealth Law Reports.

13 2 Black 635, at pp. 666-7.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

468 The International Law Quarterly [VOL. 4

same. . . . These rights the United States exercised ag

and all other nations, and did it in virtue of the fact of w

because of the recognition of the belligerency of the

those powers or any one of them '.14

One could produce numerous examples of de facto

nection with civil wars all tending to show that in practic

when the facts of war exist. The same is true in international

hostilities, for 'the principles of the laws of war . . . are in the

essence independent of the formal status of the parties to

struggle. The same considerations of humanity, the same fear

reprisals, and the same desire to avoid involvement exist, whet

it be a civil or an international war '.1" Thus, in the Kelley Cas

(1930)"' the United States-Mexican General Claims Commission

concerned with a claim arising out of the activities of Gen

Huerta in Mexico. In 1914 American forces landed at Vera Cruz

and, after engaging in hostilities with Mexican troops, occupied

city. In the words of the Commission, the ' President expressed

"deep and genuine friendship " on the part of the American peop

for the people of Mexico, and he stated that he earnestly hoped t

war was not at the time in question. However, there was fighti

between the Mexican and American forces and the city of Vera C

was occupied.... In whatever light the landing of American troo

at Vera Cruz and the clash of military forces that followed may

viewed, it seems to be clear that when these occurrences took pl

. . . hostilities of some considerable duration may reasonably ha

been anticipated. . ... Without undertaking to classify the inciden

of 1914 at Vera Cruz in precise terms of the international law p

taining to war, or measures stopping short of war, or something else

or to apply to such incidents concrete rules of that law, we are

opinion that a proper disposition of the present case may be fou

in principles of law to which proper application may be given i

determining the question of international responsibility '."

Commission then proceeded to refer to 'non-combatants' and

employ other terms which only have meaning in war, includin

lengthy analysis of trading with the enemy. Despite the no

existence of any de jure war the Commission applied practical te

and made full use of analogies drawn from the laws of war, trea

both parties as belligerents.

It would appear from what has been said, and regardless of

situation in municipal law, that from the point of view of int

national law a war is being fought in Korea whether the parties t

describe it as a de facto or a de jure war. L. C. GREEN.

14 3 Moore, International Arbitrations, p. 2886, at pp. 2888-9.

15 Chen, The International Law of Recognition, 1951, p. 356.

16 Opinions of the Commissioners, 1931, p. 82. 17 Ibid., pp. 85, 84.

This content downloaded from

157.40.86.82 on Sun, 19 Mar 2023 05:28:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- War Law: Understanding International Law and Armed ConflictFrom EverandWar Law: Understanding International Law and Armed ConflictRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Building Bridges Not Walls Final ReportDocument35 pagesBuilding Bridges Not Walls Final Reportben7872No ratings yet

- The Case Against WarDocument270 pagesThe Case Against WarDaniel SolisNo ratings yet

- Hartzel v. United States, 322 U.S. 680 (1944)Document10 pagesHartzel v. United States, 322 U.S. 680 (1944)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dennis MORA Et AlDocument5 pagesDennis MORA Et AlGRAND LINE GMSNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Waldron, Torture and Positive LawDocument67 pagesJeremy Waldron, Torture and Positive LawChirtu Ana-MariaNo ratings yet

- Noto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290 (1961)Document9 pagesNoto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290 (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Britain and Its Mandate over Palestine: Legal Chicanery on a World StageFrom EverandBritain and Its Mandate over Palestine: Legal Chicanery on a World StageNo ratings yet

- Three - Fifths.pereeson - More.than - Cow.an - Insurrecting.cow 01FinkelmanVol.43.3Document34 pagesThree - Fifths.pereeson - More.than - Cow.an - Insurrecting.cow 01FinkelmanVol.43.3reidrenNo ratings yet

- Law Divided into Substantive and AdjectiveDocument9 pagesLaw Divided into Substantive and Adjectivegivamathan100% (1)

- LEGAL ASSIGDocument15 pagesLEGAL ASSIGRohan BhumkarNo ratings yet

- Gerrit, What Does RC Stands For?: ConstitutionalistDocument5 pagesGerrit, What Does RC Stands For?: ConstitutionalistGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- International Law and The Use of Force: What Happens in Practice?Document23 pagesInternational Law and The Use of Force: What Happens in Practice?Yashika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Application of Absent Sovereign Law in Occupied TerritoryDocument31 pagesApplication of Absent Sovereign Law in Occupied TerritoryNatalina Dass Tera LodatoNo ratings yet

- South Korea Truth Commission: Preliminary ReportDocument143 pagesSouth Korea Truth Commission: Preliminary ReportCEInquiryNo ratings yet

- This Side of Silence: Human Rights, Torture, and the Recognition of CrueltyFrom EverandThis Side of Silence: Human Rights, Torture, and the Recognition of CrueltyNo ratings yet

- Those Forgotten SoldiersDocument7 pagesThose Forgotten SoldiersKyle TatumNo ratings yet

- Farlin Research Paper Pol407 - The War Powers Resolution of 1973Document15 pagesFarlin Research Paper Pol407 - The War Powers Resolution of 1973api-700323027No ratings yet

- MG - Co.za Deep Read The Blair Necessity Opinion Comment and AnalysisDocument2 pagesMG - Co.za Deep Read The Blair Necessity Opinion Comment and AnalysisSCRUPEUSSNo ratings yet

- The Third Zionist War - 1951 by George W. ArmstrongDocument69 pagesThe Third Zionist War - 1951 by George W. ArmstrongKeith Knight100% (1)

- Neutral Rights and Obligations in the Anglo-Boer WarFrom EverandNeutral Rights and Obligations in the Anglo-Boer WarNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of The Declaration of IndependeceDocument6 pagesThe Analysis of The Declaration of IndependeceNarendran Sairam100% (3)

- Korematsu v. United States Research PaperDocument7 pagesKorematsu v. United States Research Papernepwuhrhf100% (1)

- Lawyer PDFDocument274 pagesLawyer PDFbaabdullahNo ratings yet

- Civil War Term PapersDocument4 pagesCivil War Term Papersea6xrjc4100% (1)

- Turning Points: The Role of the State Department in Vietnam (1945–1975)From EverandTurning Points: The Role of the State Department in Vietnam (1945–1975)No ratings yet

- To Raise and Discipline an Army: Major General Enoch Crowder, the Judge Advocate General’s Office, and the Realignment of Civil and Military Relations in World War IFrom EverandTo Raise and Discipline an Army: Major General Enoch Crowder, the Judge Advocate General’s Office, and the Realignment of Civil and Military Relations in World War INo ratings yet

- Esej Divided N IrelandDocument11 pagesEsej Divided N IrelandNataliaNo ratings yet

- An Open Letter To His Excellency Ban Ki Mon DraftDocument3 pagesAn Open Letter To His Excellency Ban Ki Mon DraftဒီမိုေဝယံNo ratings yet

- Law in War: Freedom and restriction in Australia during the Great WarFrom EverandLaw in War: Freedom and restriction in Australia during the Great WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- SSRN Id461721Document25 pagesSSRN Id461721Akhmad Fikri YahmaniNo ratings yet

- Armstrong - Korea & VietnamDocument15 pagesArmstrong - Korea & VietnamLiuLingNo ratings yet

- The Tokyo JudgementDocument29 pagesThe Tokyo JudgementRyan CamachoNo ratings yet

- English Legal System Coursework 2009Document7 pagesEnglish Legal System Coursework 2009monicaomidvarNo ratings yet

- Sexual Slavery and The Comfort Women of World War IIDocument16 pagesSexual Slavery and The Comfort Women of World War IIiamjasfNo ratings yet

- ICL Project 7th SemesterDocument18 pagesICL Project 7th SemesterAstha DehariyaNo ratings yet

- Congress Surrenders The War Powers: Libya, The United Nations, and The Constitution, Cato Policy Analysis No. 687Document32 pagesCongress Surrenders The War Powers: Libya, The United Nations, and The Constitution, Cato Policy Analysis No. 687Cato Institute100% (1)

- Korean War Research PaperDocument6 pagesKorean War Research Paperfveec9sx100% (1)

- Command Responsibility For War Crimes - Parks V7.130216Document102 pagesCommand Responsibility For War Crimes - Parks V7.130216Exo MxyzptlcNo ratings yet

- Prosecutor V TadicDocument18 pagesProsecutor V TadicTafadzwa ChamisaNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth HistoryDocument19 pagesThe Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth HistoryTrepNo ratings yet

- Sambiaggio Case Short SummaryDocument10 pagesSambiaggio Case Short SummaryJean Jamailah TomugdanNo ratings yet

- Currentevent 1Document3 pagesCurrentevent 1api-359004798No ratings yet

- SSRN-Id1374454-Law, War, and The History of TimeDocument45 pagesSSRN-Id1374454-Law, War, and The History of TimeSapodriloNo ratings yet

- Pol and ToT 1Document18 pagesPol and ToT 1Deon FernandesNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-99 November 16, 1945 caseDocument316 pagesG.R. No. L-99 November 16, 1945 caseryan_macadangdangNo ratings yet

- U.S. Supreme Court Case on Military Tribunal AuthorityDocument51 pagesU.S. Supreme Court Case on Military Tribunal AuthorityJohanes Alverandy ArioNo ratings yet

- 15 Sydney LRev 3Document28 pages15 Sydney LRev 3Liam ScullyNo ratings yet

- US Vs Delos ReyesDocument6 pagesUS Vs Delos ReyesDagul JauganNo ratings yet

- Nishikawa v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 129 (1958)Document14 pagesNishikawa v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 129 (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Historical Review Volume 09 - Number - 2-1989Document127 pagesThe Journal of Historical Review Volume 09 - Number - 2-1989wahrheit88No ratings yet

- The Caroline Incident and Article 51 of The United Nations Charte1Document2 pagesThe Caroline Incident and Article 51 of The United Nations Charte1Abdul SattarNo ratings yet

- EXONERATION FINALLY!: The true story of a Vietnam reporter’s fight to prevent conviction by the US governmentFrom EverandEXONERATION FINALLY!: The true story of a Vietnam reporter’s fight to prevent conviction by the US governmentNo ratings yet

- Assassination of Lincoln: A History of the Great Conspiracy. Trial of the Conspirators by a Military Commission, and a Review of the Trial of John H. SurrattFrom EverandAssassination of Lincoln: A History of the Great Conspiracy. Trial of the Conspirators by a Military Commission, and a Review of the Trial of John H. SurrattNo ratings yet

- Takatori Tokyo Trial FinalityDocument20 pagesTakatori Tokyo Trial FinalityCrisCastro100% (1)

- Association For Asian Performance (AAP) of The Association For Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE), University of Hawai'i Press Asian Theatre JournalDocument4 pagesAssociation For Asian Performance (AAP) of The Association For Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE), University of Hawai'i Press Asian Theatre JournalSubhoNo ratings yet

- Binodini Dasi My Story and My Life As An Actress ReviewDocument4 pagesBinodini Dasi My Story and My Life As An Actress ReviewSubho100% (1)

- 'Public Women' - Early Actresses of The Bengali Stage-Role and RealityDocument29 pages'Public Women' - Early Actresses of The Bengali Stage-Role and RealitySubhoNo ratings yet

- (Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, 93) Rini Bhattacharya Mehta (Editor), Debali Mookerjea-Leonard (Editor) - The Indian Partition in Literature and Films_ History, Politics, And Aesthetics-RouDocument205 pages(Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, 93) Rini Bhattacharya Mehta (Editor), Debali Mookerjea-Leonard (Editor) - The Indian Partition in Literature and Films_ History, Politics, And Aesthetics-Rousuprnd79No ratings yet

- The 'Beshya' and The 'Babu' - Prostitute and Her Clientele in 19th Century BengalDocument13 pagesThe 'Beshya' and The 'Babu' - Prostitute and Her Clientele in 19th Century BengalSubhoNo ratings yet

- DERIVATIONDocument2 pagesDERIVATIONSubhoNo ratings yet

- Sociology and HistoryDocument3 pagesSociology and HistorySubhoNo ratings yet

- Sociology and HistoryDocument3 pagesSociology and HistorySubhoNo ratings yet

- Weber's view of action and subjective meaningDocument1 pageWeber's view of action and subjective meaningSubhoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledSubhoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledSubhoNo ratings yet

- CRAC Lecture Series - On Bravo - Sir SandovalDocument128 pagesCRAC Lecture Series - On Bravo - Sir SandovalJam JamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument2 pagesChapter 4 - Doctrine of State ImmunityAaron Te100% (4)

- Communist Marxist Rule in IndiaDocument13 pagesCommunist Marxist Rule in Indiaharahara sivasivaNo ratings yet

- Security Guard ModuleDocument65 pagesSecurity Guard Moduleshela lapeña100% (1)

- UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM THROUGH FAIRNESSTITLEDocument50 pagesUNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM THROUGH FAIRNESSTITLEArianne SagumNo ratings yet

- Genealogy of The National-Popular Project of Social Transformation in The Philippines (1896-1940)Document25 pagesGenealogy of The National-Popular Project of Social Transformation in The Philippines (1896-1940)Cha BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- BNM Case Study DefinitionsDocument3 pagesBNM Case Study DefinitionsBhavesh JaniNo ratings yet

- 1906arunachala Tyaga RajanDocument2 pages1906arunachala Tyaga Rajanmahadi473No ratings yet

- Islamic Political PhilosophyDocument8 pagesIslamic Political PhilosophyKhalil-Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Memo On BIDA ProgramDocument52 pagesMemo On BIDA ProgramBarangay Mabulo100% (2)

- California Residential Purchase AgreementDocument11 pagesCalifornia Residential Purchase AgreementKoko CatedrillaNo ratings yet

- PFR Review Syllabus USC 2021Document38 pagesPFR Review Syllabus USC 2021Tatak BuganonNo ratings yet

- Expressing Nationalism in the PhilippinesDocument3 pagesExpressing Nationalism in the Philippinesxcxcxcscs gsksksknsnsNo ratings yet

- Consti 1 NotesDocument7 pagesConsti 1 NotesCatNo ratings yet

- Temporary Resident Visa Application InstructionsDocument13 pagesTemporary Resident Visa Application Instructionsnaik16No ratings yet

- Letter President of Ecuador Rafael CorreaDocument1 pageLetter President of Ecuador Rafael CorreaMichael GaardsøeNo ratings yet

- 1st Exam Criminal Justice System 121Document34 pages1st Exam Criminal Justice System 121ceilo trondilloNo ratings yet

- NIYOGA Smita Sahgal PDFDocument36 pagesNIYOGA Smita Sahgal PDFAnshika SinghNo ratings yet

- IRFR 420-IRFU 420-SiHFR420-SiHFU420 - MosfetDocument11 pagesIRFR 420-IRFU 420-SiHFR420-SiHFU420 - MosfetTiago LeonhardtNo ratings yet

- Simon Morris Deputy Chief Executive Complaint Case 1220093Document4 pagesSimon Morris Deputy Chief Executive Complaint Case 1220093CharonNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of TaaghootDocument2 pagesThe Meaning of TaaghootAl FurqaanNo ratings yet

- 3 Labor Reviewer - Labor StandardsDocument25 pages3 Labor Reviewer - Labor StandardsBiboy GSNo ratings yet

- Ideologies' Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument1 pageIdeologies' Advantages and DisadvantagesKamil DumpNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) : "Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls."Document3 pagesSustainable Development Goals (SDGS) : "Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls."Peter Odosamase OsifoNo ratings yet

- B5a 2105 10Document128 pagesB5a 2105 10Moto MotoNo ratings yet

- Theories (Juvenile Delinquency) : Strain TheoryDocument15 pagesTheories (Juvenile Delinquency) : Strain TheoryJim CB LunagNo ratings yet

- Tender Evaluation Report for PROJECT NAME ConstructionDocument7 pagesTender Evaluation Report for PROJECT NAME ConstructionDanny EricoNo ratings yet

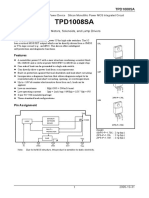

- TPD1008SA High-Side Power Switch GuideDocument11 pagesTPD1008SA High-Side Power Switch GuideOlga PlohotnichenkoNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Local SelfDocument4 pagesEvolution of Local SelfAyush DuttaNo ratings yet

- Charles Tilly From Mobilization To RevolutionDocument192 pagesCharles Tilly From Mobilization To RevolutionVasilije Luzaic100% (1)