Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articles: Background

Uploaded by

DayannaPintoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles: Background

Uploaded by

DayannaPintoCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Antepartum dalteparin versus no antepartum dalteparin for

the prevention of pregnancy complications in pregnant

women with thrombophilia (TIPPS): a multinational

open-label randomised trial

Marc A Rodger, William M Hague, John Kingdom, Susan R Kahn, Alan Karovitch, Mathew Sermer, Anne Marie Clement, Suzette Coat,

Wee Shian Chan, Joanne Said, Evelyne Rey, Sue Robinson, Rshmi Khurana, Christine Demers, Michael J Kovacs, Susan Solymoss, Kim Hinshaw,

James Dwyer, Graeme Smith, Sarah McDonald, Jill Newstead-Angel, Anne McLeod, Meena Khandelwal, Robert M Silver, Gregoire Le Gal,

Ian A Greer, Erin Keely, Karen Rosene-Montella, Mark Walker, Philip S Wells, for the TIPPS Investigators

Summary

Background Thrombophilias are common disorders that increase the risk of pregnancy-associated venous Published Online

thromboembolism and pregnancy loss and can also increase the risk of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications July 25, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

(severe pre-eclampsia, small-for-gestational-age infants, and placental abruption). We postulated that antepartum S0140-6736(14)60793-5

dalteparin would reduce these complications in pregnant women with thrombophilia.

See Online/Comment http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-

Methods In this open-label randomised trial undertaken in 36 tertiary care centres in five countries, we enrolled 6736(14)60850-3

consenting pregnant women with thrombophilia at increased risk of venous thromboembolism or with previous Thrombosis Program, Division

placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. Eligible participants were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either of Hematology, Department of

Medicine, University of

antepartum prophylactic dose dalteparin (5000 international units once daily up to 20 weeks’ gestation, and twice daily

Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

thereafter until at least 37 weeks’ gestation) or to no antepartum dalteparin (control group). Randomisation was done (Prof M A Rodger MD); Ottawa

by a web-based randomisation system, and was stratified by country and gestational age at randomisation day with a Hospital Research Institute,

permuted block design (block sizes 4 and 8). At randomisation, site pharmacists (or delegates) received a randomisation Ottawa, ON, Canada

(Prof M A Rodger,

number and treatment allocation (by fax and/or e-mail) from the central web randomisation system and then dispensed

A M Clement RN,

study drug to the local coordinator. Patients and study personnel were not masked to treatment assignment, but the Prof G Le Gal MD,

outcome adjudicators were masked. The primary composite outcome was independently adjudicated severe or early- Prof E Keely MD, M Walker MD,

onset pre-eclampsia, small-for-gestational-age infant (birthweight <10th percentile), pregnancy loss, or venous Prof P S Wells MD); Obstetric

Medicine, Robinson Institute,

thromboembolism. We did intention-to-treat and on-treatment analyses. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov,

University of Adelaide,

number NCT00967382, and with Current Controlled Trials, number ISRCTN87441504. Women’s and Children’s

Hospital, Adelaide, South

Findings Between Feb 28, 2000, and Sept 14, 2012, 292 women consented to participate and were randomly assigned Australia, Australia

(Prof W M Hague MD); Division

to the two groups. Three women were excluded after randomisation because of ineligibility (two in the antepartum

of Maternal-Fetal Medicine,

dalteparin group and one in the control group), leaving 146 women assigned to antepartum dalteparin and 143 assigned Department of Obstetrics and

to no antepartum dalteparin. Some patients crossed over to the other group during treatment, and therefore for on- Gynecology, Mount Sinai

treatment and safety analysis there were 143 patients in the dalteparin group and 141 in the no dalteparin group. Hospital, University of Toronto,

Toronto, ON, Canada

Dalteparin did not reduce the incidence of the primary composite outcome in both intention-to-treat analysis (Prof J Kingdom MD,

(dalteparin 25/146 [17·1%; 95% CI 11·4–24·2%] vs no dalteparin 27/143 [18·9%; 95% CI 12·8–26·3%]; risk difference Prof M Sermer MD); Centre for

−1·8% [95% CI –10·6% to 7·1%)) and on-treatment analysis (dalteparin 28/143 [19·6%] vs no dalteparin 24/141 Clinical Epidemiology, Jewish

[17·0%]; risk difference +2·6% [95% CI –6·4 to 11·6%]). In safety analysis, the occurrence of major bleeding did not General Hospital, Montreal, QC,

Canada (Prof S R Kahn MD);

differ between the two groups. However, minor bleeding was more common in the dalteparin group (28/143 [19·6%]) Department of Medicine,

than in the no dalteparin group (13/141 [9·2%]; risk difference 10·4%, 95% CI 2·3–18·4; p=0·01). University of Ottawa/Ottawa

Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Interpretation Antepartum prophylactic dalteparin does not reduce the occurrence of venous thromboembolism, (A Karovitch MD, Prof G Le Gal,

Prof E Keely, Prof P S Wells);

pregnancy loss, or placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in pregnant women with thrombophilia at high risk Robinson Institute, University

of these complications and is associated with an increased risk of minor bleeding. of Adelaide, Adelaide, South

Australia, Australia

Funding Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and Pharmacia and UpJohn. (S Coat PhD); Department of

Medicine, University of British

Columbia, Vancouver, BC,

Introduction women.2 Thrombophilia acts synergistically with Canada (W S Chan MD);

Thrombophilias are common acquired or genetic pregnancy to increase further the risk of venous Maternal Fetal Medicine,

NorthWest Academic Center,

predispositions to develop venous thromboembolism.1 thromboembolism during pregnancy.3

University of Melbourne,

Venous thromboembolism, which comprises deep vein Placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, comprising Melbourne, Australia

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is more frequent pre-eclampsia, birth of a small-for-gestational-age infant, (J Said MBBS); Departments of

in pregnant women than in non-pregnant age-matched placental abruption, or pregnancy loss, are also common4,5 Medicine and Obstetrics and

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 1

Articles

Gynecology, University of and lead to substantial maternal and fetal or neonatal the Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia), or the

Montreal, and CHU Sainte- morbidity and mortality.4 Placental microvascular and Medicines and Healthcare Product Regulatory Agency

Justine Research Center,

Montreal, QC, Canada

macrovascular thrombosis is a frequent, overlapping, (UK), and local research ethics board approvals before we

(E Rey MD); Department of pathophysiological link in many affected pregnancies.5 began the study. All women participating in the study

Medicine, Dalhousie University, Patients with previous placenta-mediated pregnancy provided written informed consent.

Halifax, NS, Canada complications have a raised risk of both recurrent We screened 3022 women with previous pregnancy

(Prof S Robinson MD);

Departments of Medicine and

placenta-mediated pregnancy complications6 and venous complications, venous thromboembolism risk factors, or

Obstetrics and Gynecology, thromboembolism during subsequent pregnancies.7,8 thrombophilia for eligibility. Women were eligible for

University of Alberta, Royal Similarly, evidence suggests that women with previous inclusion if they had a confirmed thrombophilia (panel 1),

Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton,

venous thromboembolism have a raised risk of placenta- were at raised risk of placenta-mediated pregnancy

AB, Canada (R Khurana MD);

Department of Medicine, mediated pregnancy complications in subsequent complications or venous thromboembolism (panel 1),

Université de Laval, Quebec, QC, pregnancies.9 were pregnant, and had provided written informed

Canada (C Demers MD); Thrombophilias are consistently associated with early consent. Women were excluded if they were 21 weeks or

Department of Medicine,

and late pregnancy loss10,11 and can also be related to more gestational age at the time of randomisation, had a

London Health Sciences Centre,

University of Western Ontario, severe pre-eclampsia, birth of a small-for-gestational-age contraindication to heparin treatment (panel 1), were

London, ON, Canada infant below the third percentile of birthweight, and geographically inaccessible, needed anticoagulant therapy

(Prof M J Kovacs MD); placental abruption.10 Since the initial discovery of an as judged by the local investigator (panel 1), had already

Department of Medicine, McGill

association between thrombophilia and placenta- previously participated in the study, or were younger than

University, St Mary’s Hospital

Center, Montreal, QC, Canada mediated pregnancy complications more than 15 years the legal lower age limit to provide consent according to

(S Solymoss MD); Department of ago,12 clinicians, patients, guideline developers, and policy country-specific regulations. We maintained screening

Obstetrics, Sunderland Royal makers have struggled to address the question of whether records to detail any reason for ineligibility in all patients

Hospital, Sunderland, Tyne and

pregnant women with thrombophilia should receive approached for the study.

Wear, UK (K Hinshaw MBBS);

Department of Obstetrics and antepartum thromboprophylaxis.13

Gynaecology, York Hospital, Low-molecular-weight heparin is the thrombo- Randomisation and masking

York, UK (J Dwyer MBBS); prophylactic drug of choice in pregnancy because, unlike After confirming eligibility and obtaining consent, research

Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Queen’s University,

oral anticoagulants, it does not cross the placenta and has a coordinators at each centre randomly assigned eligible

Kingston, ON, Canada favourable maternal safety profile with a low risk of major patients in a 1:1 ratio to antepartum dalteparin or no

(Prof G Smith MD); Division of bleeding, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and antepartum dalteparin by a web-based randomisation

Maternal-Fetal Medicine, heparin-induced osteoporosis.14 Nonetheless, the drug system. The computer-generated randomisation schedule

Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Department of

needs to be administered by burdensome daily or twice was stratified by country and gestational age at

Radiology, and Department of daily subcutaneous injections, is expensive, and can randomisation day (<8 weeks, 8–12 weeks, and 12–20 weeks)

Clinical Epidemiology and complicate regional anaesthetic options if not discontinued and had a permuted block design (block sizes 4 and 8). At

Biostatistics, McMaster within 12–24 h of labour onset. the time of randomisation, site pharmacists (or delegates)

University, Hamilton, ON,

Canada (S McDonald MD);

In the Thrombophilia in Pregnancy Prophylaxis Study received a randomisation number and treatment allocation

Department of Medicine, (TIPPS) we aimed to establish whether antepartum (by fax and/or e-mail) from the central web randomisation

University of Saskatchewan, prophylactic dalteparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, system. The site pharmacist (or delegate) then dispensed

Saskatoon, SK, Canada would reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism and study drug to the local coordinator who taught the study

(J Newstead-Angel MD);

Department of Medicine,

placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in pregnant participants how to self-administer the study drug and

Sunnybrook Health Sciences women with thrombophilia at high risk of pregnancy explained the trial procedures. Patients and study personnel

Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada complications. were not masked but outcome adjudicators were masked to

(A McLeod MD); Department of treatment assignment.

Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Cooper Medical School of Methods

Rowan University/Cooper Study design and participants Procedures

Hospital, Camden, NJ, USA We enrolled pregnant women with thrombophilia who We randomly assigned 292 women to receive either

(Prof M Khandelwal MD);

were at increased risk of placenta-mediated pregnancy antepartum dalteparin 5000 international units (IU)

Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, University of Utah complications, venous thromboembolism, or both in a once daily by subcutaneous self-injection from the day

Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake randomised trial to compare prophylactic dose antepartum of randomisation until 20 weeks of gestation followed

City, UT, USA dalteparin with no antepartum dalteparin. Between by 5000 IU twice daily from 20 weeks until at least

(Prof R M Silver MD); Faculty of

Feb 28, 2000, and Sept 14, 2012, the study was initiated in 37 weeks gestational age, or no antepartum dalteparin.

Health and Life Sciences,

University of Liverpool, 36 tertiary care centres in Canada, Australia, the USA, the The dose of dalteparin was doubled at 20 weeks’

Liverpool, UK (Prof I A Greer MD); UK, and France. 26 of these 36 centres screened patients gestation on the basis of pharmacokinetic studies

and Department of Medicine, for eligibility (the other ten did not because they were suggesting that the dose requirement increases in most

The Warren Alpert Medical

either unable to implement local trial operations or get women after this point.15 During the initial 26 months

School of Brown University,

Women’s Medicine referrals to screen potentially eligible patients) and of the study, the control group received matching,

Collaborative, Providence, RI, 21 centres recruited at least one patient. We obtained identically supplied and formulated placebo in prefilled

USA (Prof K Rosene-Montella MD) appropriate regulatory approvals from Health Canada syringes. Owing to poor recruitment (only 19 participants

(Canada), the US Food and Drug Administration (USA), were recruited in 26 months), on June 25, 2002, the trial

2 www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5

Articles

Correspondence to:

Panel 1: Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria Prof Marc A Rodger, Ottawa

Hospital, General Campus,

Inclusion criteria (1, 2, 3, and 4 must have been met for 3 Pregnancy confirmed by a positive serum, or urine 501 Smyth Road, Box 201A,

inclusion): βhCG, or by ultrasound Ottawa, ON, K1H 8L6, Canada

4 Signed informed consent mrodger@ohri.ca

1 Thrombophilia confirmed by one or more of the following:

1·1 Factor V Leiden: one positive DNA based assay for factor V Exclusion criteria (any one criterion met led to exclusion):

Leiden (homozygous or heterozygous), or documented

1 21 weeks or more gestational age at time of randomisation

activated protein C resistance and a first-degree relative

testing positive once for factor V Leiden in a DNA-based assay 2 Contraindication to heparin therapy, including:

1·2 Prothrombin gene mutation (homozygous or heterozygous) in 2·1 History of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

a DNA-based assay 2·2 Platelet count lower than 100 000 × 106/L

or 2·3 History of osteoporosis or steroid use (potential

Two abnormal tests, and no normal tests, for one or more of increased risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic

the following: fracture with heparin therapy)

1·3 Protein C deficiency 2·4 Actively bleeding

1·4 Protein S deficiency: at least one test done outside 2·5 Documented peptic ulcer within 6 weeks

pregnancy or the 6 week post-partum period, or, in addition (contraindication to anticoagulation)

to two abnormal tests in pregnancy, one abnormal test 2·6 Heparin, bisulphite, or fish allergy

obtained in a first-degree relative 2·7 Severe hypertension (systolic blood pressure

1·5 Antithrombin deficiency >200 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure

or >120 mm Hg: contraindication to anticoagulation)

1·6 Anti-phospholipid antibody confirmed by two positive tests 2·8 Severe hepatic failure (international normalised ratio

for one or more of the following: anticardiolipin IgG >1·8): increased likelihood of bleeding

(>30 U/ml), anticardiolipin IgM (>30 U/ml), anti-β2 2·9 Women with serum creatinine level greater than

glycoprotein IgG (>20 U/ml), anti-β2 glycoprotein IgM 80 μmol/L (1·3 mg/dL) and 24-h creatinine clearance

(>20 U/ml), or positive Lupus anticoagulant less than 30 mL/min. However, women with serum

creatinine clearance of 80 μmol/L (1·3 mg/dL) or less

2 One or more of the following high-risk criteria for

did not require a normal 24-h creatinine clearance to

pregnancy complications (venous thromboembolism,

be eligible.

pregnancy loss, or placenta-mediated complications):

2·1 Previous history of pre-eclampsia (including late-onset and 3 Geographical inaccessibility (less likely to comply with

non-severe pre-eclampsia) necessary follow-up visits and care)

2·2 Previous unexplained birth of a small-for-gestational-age

4 Need for anticoagulants as judged by the local

infant (birthweight <10th percentile, corrected for sex and

investigator, including (but not limited to):

gestational age)

4·1 Women with recurrent pregnancy loss with

2·3 Previous major placental abruption, defined as an abruption

antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

associated with: vaginal bleeding or concealed

4·2 Women with previous unprovoked§ proximal¶

haemorrhage, and uterine tenderness, and fetal distress,

venous thromboembolism, whose pulmonary

maternal shock, or maternal coagulopathy

embolism or deep vein thrombosis was treated with

2·4 Previous pregnancy loss* defined as:

anticoagulants (more than 1 month of heparin or

2·4·1 Three or more unexplained pregnancy losses at

warfarin) or inferior vena cava interruption

less than 10 weeks’ gestation, or

4·3 Women with mechanical heart valves

2·4·2 Two or more unexplained pregnancy losses between

4·4 Women on long-term anticoagulants before

10 and 16 weeks’ gestation, or

pregnancy

2·4·3 One or more unexplained pregnancy losses at or more

than 16 weeks’ gestation 5 Previous participation in the TIPPS trial

2·5 Women with a history of one or more of the following

6 Below the legal age limit to provide informed consent

thromboembolic events/risk factors:

according to country-specific regulations

2·5·1 Previous documented provoked proximal† venous

thromboembolism *Examples of explained miscarriage or fetal loss include loss associated with severe congenital

2·5·2 Previous documented calf vein‡ thrombosis malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, neonatal alloimmune haemolytic anaemia,

recent cytomegalovirus infection, positive fetal or placental listeria cultures, and women with

2·5·3 Previous superficial phlebitis known abnormal uterine anatomy. †Proximal venous thromboembolism includes pulmonary

2·5·4 A first-degree relative with a history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis occurring at or above the trifurcation of the popliteal vein.

‡Calf vein thrombosis is a deep vein thrombosis that occurs below the trifurcation of the

embolism or deep vein thrombosis treated with

popliteal vein. §Unprovoked refers to a venous thromboembolism that occurs outside all of

anticoagulants (more than 1 month of heparin or the following periods: surgery, immobilisation, cast, and/or malignancy. ¶Proximal refers to a

warfarin) venous thromboembolism that occurs above the trifurcation of the popliteal vein.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 3

Articles

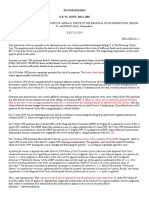

3022 women assessed for eligibility

2730 excluded

2378 did not meet eligibility criteria

175 had ≥1 exclusion criteria

177 refused to participate

292 randomised

148 initially allocated to antepartum dalteparin 144 initially allocated to no antepartum dalteparin

2 excluded for ineligibility 1 excluded for ineligibility

146 allocated to antepartum dalteparin 143 allocated to no antepartum dalteparin

12 crossed over to the control group 14 crossed over to the antepartum

dalteparin group

14 patients crossed over from other group 12 patients crossed over from other group

148 received antepartum dalteparin 141 received no antepartum dalteparin

0 lost to follow-up (note: 3 patients did not 0 lost to follow-up (note: 6 patients did not

have a 6-week post-partum visit) have a 6-week post-partum visit)

15 non-compliant with dalteparin 14 non-compliant with post-partum

1 had <80% antepartum doses dalteparin (<80% post-partum doses)

10 had <80% post-partum doses

4 had <80% doses in both periods

146 women in intention-to-treat analysis 143 women in intention-to-treat analysis

143 women in on-treatment and safety analyses* 141 women in on-treatment and safety analyses

Figure 1: Trial profile

*The five patients who were non-compliant with antepartum dalteparin were excluded from the on-treatment and safety analyses.

steering committee changed the study design to an assessment for protein and blood, complete blood

open-label trial comparing antepartum open-label count, and serum creatinine and liver function tests.

dalteparin with no antepartum dalteparin control. Post Bone mineral density was measured at the 6-week post-

partum, all participants were prescribed dalteparin at a partum visit. Additionally, follow-up visits, either in

dose of 5000 IU once daily by subcutaneous self- person or on the telephone, were done at 8, 16, 24, 30,

injection from day 1 (administered 6–28 h after delivery) 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, and 40 weeks’ gestation. We assessed

until day 42. All participants received otherwise similar outcomes and adverse events at the time of labour and

obstetrical care (according to local practices) and study delivery by review of participants’ medical records and

follow-up. any gaps were resolved at the 6 weeks post-partum

We defined crossovers as participants who switched follow-up visit.

study groups within 10 days of randomisation.

Participants who discontinued dalteparin after 10 days Outcomes

were labelled as non-compliant. Throughout study The primary endpoint was a composite outcome that

follow-up, we recorded cointerventions (eg, aspirin) and included any of the following events: objectively

concomitant use of other medications. documented symptomatic major venous thrombo-

Patients attended clinic follow-up visits within embolism (deep vein thrombosis proximal to the calf

7–9 days of randomisation and then at 12, 20, 28, 32, trifurcation, pulmonary embolism, or sudden maternal

36 weeks’ gestation and at 6 weeks post partum. These death); severe or early-onset (<32 weeks) pre-eclampsia

visits included assessments of outcome and adverse (defined as severe if accompanied by blood pressure

events, measurement of weight and blood pressure, ≥160/110 mm Hg or liver function tests three-times

study drug compliance diary review, urine dipstick above normal limits, platelet count <100 000 × 10⁶/L,

4 www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5

Articles

oliguria [<30 mL/h urine output in a 24 h period], Hemostasis17) and minor bleeding (non-major bleeding),

pulmonary oedema [on chest x-ray], coagulopathy bone mineral density measured at 6 weeks post partum,

[partial thromboplastin time >1·5 ×baseline, preterm delivery, placental abruption, heparin-induced

international normalised ratio >1·5 ×baseline, or thrombocytopenia, and symptomatic fracture.

fibrinogen <1·0 g/dL], proteinuria >5 g/24 h, or All suspected primary and secondary outcome events

seizures); birth of a small-for-gestational-age infant were adjudicated independently and blindly by at least

(birthweight <10th percentile);16 or pregnancy loss. two physicians in a panel that included experts in

Placental abruption was not included in the composite obstetrics and thrombosis.

primary outcome because of the hypothetical possibility

that dalteparin might increase the frequency of this

Antepartum No

bleeding complication. dalteparin antepartum

Secondary outcomes included major bleeding (as group dalteparin

defined by the International Society of Thrombosis and (n=146) group (n=143)

(Continued from previous column)

Antepartum No High-risk inclusion criteria

dalteparin antepartum

Previous pregnancy complications 92 (63%) 84 (59%)

group dalteparin

(any of those listed below)

(n=146) group (n=143)

Pre-eclampsia 20 (14%) 25 (18%)

Age (years) 31·9 (4·7) 31·6 (5·1)

Eclampsia 3 (2%) 3 (2%)

Gestational age at randomisation 12·0 (4·5) 11·7 (4·7)

(weeks) SGA infant (<10th percentile) 26 (18%) 19 (13%)

Ethnic origin Major placental abruption 16 (11%) 10 (7%)

White 133 (91%) 129 (90%) Three or more miscarriages at 24 (16%) 20 (14%)

<10 weeks’ gestation

Black 3 (2%) 3 (2%)

Two or more fetal losses at 11 (8%) 14 (10%)

Asian 8 (6%) 4 (3%) 10–16 weeks’ gestation

Native Canadian 0 3 (2%) One or more fetal losses at 27 (19%) 33 (23%)

Other 2 (1%) 4 (3%) ≥16 weeks’ gestation

Smoking status VTE risk factors/events (any of the 67 (46%) 61 (43%)

Ever smoker 56 (38%) 51 (36%) following)

Current smoker 5 (3%) 4 (3%) Family history of VTE in first- 45 (31%) 46 (32%)

degree relatives

BMI (kg/m²)

Mean number of first-degree 1·1 1·1

Pre-pregnancy 26·3 (6·6) 27·0 (6·8) relatives with VTE, per participant

At time of randomisation 27·7 (6·8) 27·8 (6·5) Previous secondary VTE 11 (8%) 9 (6%)

Baseline blood pressure (mm Hg) Previous calf deep vein thrombosis 10 (7%) 6 (4%)

Systolic 112·3 (12·0) 114·4 (12·6) Previous superficial phlebitis 7 (5%) 5 (4%)

Diastolic 67·9 (8·9) 69·6 (9·5) Concurrent medications during study

Obstetrical history pregnancy

Gravidity 3·1 (1·8) 3·3 (1·9) Aspirin (all participants) 43 (30%) 57 (40%)

Parity 1·0 (1·2) 1·0 (1·0) Aspirin (participants with previous 15/37 (41%) 19/28 (68%)

Preterm deliveries 0·33 (0·54) 0·32 (0·53) pre-eclampsia or SGA infants)

Spontaneous abortions 1·1 (1·48) 1·2 (1·5) Vitamins including folic acid 136 (93%) 142 (99%)

Therapeutic abortions 0·2 (0·58) 0·2 (0·45) Analgesic use in pregnancy 67 (46%) 49 (34%)

Living children 0·7 (1·0) 0·6 (0·75) Antibiotic use in pregnancy 45 (31%) 40 (28%)

Multiple pregnancies (ie, twins, 0·01 (0·1) 0·03 (0·18) Labour and delivery of study pregnancy

triplets) Induced 64 (44%) 55 (39%)

Outcomes after previous livebirths Epidural use 80 (55%) 82 (57%)

Neonatal death 13 (9%) 14 (10%) Caesarean section 61 (42%) 53 (37%)

Infant death 5 (3%) 4 (3%) Emergency caesarean section 25 (17%) 19 (13%)

Thrombophilia inclusion criteria Peri-partum haemorrhage 6 (4%) 9 (6%)

Factor V Leiden* 94 (64%) 82 (57%) Major 2 (1%) 2 (1%)

Prothrombin gene mutation 30 (21%) 33 (23%) Minor 4 (3%) 7 (5%)

Protein S deficiency 11 (8%) 13 (9%) Estimated blood loss at delivery (mL) 467·4 (201·0) 470·4 (237·1)

Protein C deficiency 6 (4%) 11 (8%)

Data are mean (SD) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. SGA=small for

Antithrombin deficiency 2 (1%) 1 (1%) gestational age. VTE=venous thromboembolism. *Four patients with

Antiphospholipid antibody 12 (8%) 10 (7%) homozygous Factor V Leiden.

(Table continues in next column)

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 5

Articles

expected minimal clinically important difference of 16%

Antepartum No antepartum Difference (95% CI) p

dalteparin dalteparin value (ie, 33% relative risk reduction), we aimed for a sample size

(n=146) (n=143) of 284 to achieve 80% power with a two-tailed α of 0·05.

Primary analysis The data safety monitoring board reviewed study

Patients with one or more of major 25 (17·1%) 27 (18·9%) −1·8% (−10·6 to 7·1) 0·70 performance and safety outcomes regularly. The board

VTE, severe or early onset also did a single planned formal blinded interim analysis

pre-eclampsia, SGA (<10%), or after 50% of study participants completed follow-up.

pregnancy loss

All data analyses were done according to a pre-

Stratified by gestational age at

randomisation

established analysis plan, with an intention-to-treat

approach. Intention-to-treat analysis was supplemented

<8 weeks 9/33 (27·3%) 12/32 (37·5%) −10·2% (−32·9 to 12·4) 0·38

by an on-treatment sensitivity analysis to assess the

8–12 weeks 9/33 (27·3%) 3/32 (9·4%) 17·9% (−0·3 to 36·1) 0·06

robustness of our findings.

12–20 weeks 7/80 (8·8%) 12/79 (15·2%) −6·4% (−16·5 to 3·6) 0·21

For the primary analysis, we compared the proportion

Stratified by location

of patients experiencing one or more of the composite

Australia 8/38 (21·0%) 8/36 (22·2%) −1·2% (−19·9 to 17·6) 0·90

outcome events between the dalteparin group and the

Canada 17/102 (16·7%) 19/104 (18·3%) −1·6% (−12·0 to 8·8) 0·76

control group using an unadjusted χ² test of proportions.

Europe 0/3 0/1 NA NA

We did prespecified subgroup analyses, in which we

USA 0/3 0/1 NA NA

analysed treatment effects in subgroups based on

Secondary analysis: efficacy outcomes

stratification variables (country and gestational age at

Symptomatic major VTE 1 (0·7%) 2 (1·4%) −0·7 (−3·1 to 1·6) 0·62

recruitment), thrombophilia, previous history of specific

Pre-eclampsia 8 (5·5%) 5 (3·5%) 2·0 (−2·8 to 6·8) 0·42 placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, and history

Severe or early onset pre- 7 (4·8%) 4 (2·8%) 2·0 (−2·4 to 6·4) 0·38 of venous thromboembolism events or risk factors.

eclampsia

In secondary analyses, for each of the binary outcomes

Small-for-gestational-age infant 9 (6·2%) 12 (8·4%) −2·2 (−8·2 to 3·8) 0·47

(<10%) (major bleeding, minor bleeding, preterm delivery,

SGA (<5%) 2 (1·4%) 3 (2·1%) −0·7 (−3·7 to 2·3) 0·68 heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and fractures), we

SGA (<3%) 3 (2·0%) 0 2·0 (−0·2 to 4·4) 0·25

used an unadjusted χ² test of proportions to compare the

Pregnancy loss (any) 12 (8·2%) 10 (7·0%) 1·2 (−4·9 to 7·3) 0·69

proportion of patients with these outcomes between the

Early (≥3 at <10 weeks) 4 (2·7%) 5 (3·5%) 0·8 (−4·8 to 3·2) 0·75

dalteparin group and the control group. We compared

mean bone mineral density, gestational age at delivery,

Late (≥2 at >10 weeks or ≥1 at 6 (4·1%) 2 (1·4%) 2·7 (−1·0 to 6·5) 0·28

>16 weeks) and birthweight in the dalteparin and control groups with

Any pre-eclampsia, SGA, or loss 27 (18·5%) 28 (19·6%) −1·1 (−10·1 to 8·0) 0·81 independent t tests. We also did on-treatment sensitivity

or abruption analyses for the primary and secondary analyses.

Placental abruption 4 (2·7%) 3 (2·1%) 0·6 (−2·9 to 4·2) 0·72 Descriptive data are presented as percentages or means

Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) 23 (15·8%) 17 (11·9%) 3·9 (−4·1 to 11·8) 0·34 (SDs). All statistical tests were two-sided and significance

Birthweight of livebirths (g) 3186·2 (758) 3241·4 (764) −55·2 (−238·6 to 0·55 was set at p<0·05. SAS version 9.3 was used for all

128·1) analyses. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov,

Gestational age at delivery (weeks) number NCT00967382, and with Current Controlled

Of livebirths 38·1 (2·84) 38·2 (3·1) −0·13 (−0·86 to 0·59) 0·72 Trials, number ISRCTN87441504.

Of pregnancy loss 16·8 (8·2) 10·8 (5·3) 6·0 (−0·09 to 12·11) 0·06

Secondary analysis: safety outcomes (on-treatment analysis) (n=143 in dalteparin group, n=141 in Role of the funding source

control group) The funders of the study had no role in the design or

Major bleeding 3 (2·1%) 2 (1·4%) 0·7 (−2·4 to 3·7) 1·0 conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and

Minor bleeding (non-major) 28 (19·6%) 13 (9·2%) 10·4 (2·3 to 18·4) 0·01 interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or

Heparin-induced 0 0 ·· ·· approval of the report. MAR, TR, RM, DF, and AMC had

thrombocytopenia

complete access to all the data in the study, and MAR,

Osteoporotic fracture 0 0 ·· ··

PSW, AK, JK, MS, WMH, SRK, WSC, and AMC had final

Bone mineral density measured at 2·16 (0·35) 2·23 (0·42) −0·07 (−0·19 to 0·04) 0·21

6 weeks post partum (g/cm³)

responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data are n (%) or mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated. VTE=venous thromboembolism. SGA=small for gestational Results

age. NA=not applicable.

Between Feb 28, 2000, and Sept 14, 2012, we approached

Table 2: Primary and secondary analysis 469 eligible women to participate in the study, of whom

292 consented and were randomly allocated to either

Statistical analysis antepartum dalteparin (n=148) or no antepartum

A priori, based on the prediction that venous dalteparin (n=144; figure 1). Three women were excluded

thromboembolism, severe or early onset pre-eclampsia, post-randomisation because of ineligibility (two in the

small-for-gestational-age infants, or pregnancy loss would antepartum dalteparin group [who received the drug but

occur in 49% of the control participants12,18–20 and an were not eligible to participate] and one in the control

6 www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5

Articles

Events/total (n/N) Risk ratio (95% CI) p value

Dalteparin Control

Subgroup

Maternal age <35 years 14/109 17/98 0·70 (0·4–1·4) 0·37

Maternal age <40 years 22/135 26/136 0·90 (0·5–1·4) 0·54

Previous pregnancy loss 14/69 17/74 0·90 (0·5–1·6) 0·70

Previous early loss 7/24 4/20 1·50 (0·5–4·3) 0·49

Previous late loss 9/37 12/44 0·90 (0·4–1·9) 0·76

Previous pre-eclampsia 7/20 6/25 1·50 (0·6–3·6) 0·42

Previous severe/early pre-eclampsia 6/13 2/9 2·10 (0·5–8·1) 0·29

Previous SGA <10% 7/26 5/19 1·02 (0·4–2·7) 0·96

Previous SGA <5% 1/3 0/1 1·50 (0·1–22·6) 0·77

Previous SGA <3% 3/13 3/11 0·80 (0·2–3·4) 0·81

Previous abruption 0/16 4/10 0·10 (0·004–1·2) 0·07

Previous secondary VTE 2/11 0/9 4·20 (0·2–77·1) 0·34

Previous calf deep vein thrombosis 0/10 3/6 0·10 (0·01–1·5) 0·09

Family history of VTE 5/45 6/46 0·80 (0·3–2·6) 0·78

Factor V Leiden 17/94 13/82 1·10 (0·6–2·2) 0·70

Prothrombin gene mutation 3/30 4/33 0·80 (0·2–3·4) 0·79

APLA 4/12 3/10 1·10 (0·3–3·8) 0·87

Protein C/protein S/antithrombin 1/19 7/25 0·20 (0·03–1·4) 0·10

Aspirin users 3/43 12/57 0·30 (0·1–1·1) 0·07

Aspirin non-users 22/103 15/86 1·20 (0·7–2·2) 0·50

0·01 0·1 1 10 100

Favours dalteparin Favours control

Figure 2: Subgroup analysis forest plot with risk ratio (95% CI) for the primary composite outcome

The primary composite outcome was major VTE or severe/early-onset pre-eclampsia, SGA infant (<10th percentile), or pregnancy loss. SGA=small for gestational age.

VTE=venous thromboembolism. APLA=anti-phospholipid antibodies.

group), leaving 146 patients assigned to antepartum >40 g/L decrease in haemoglobin at 24 h post-partum)

dalteparin and 143 to no antepartum dalteparin. were similar between groups, as was estimated blood loss

Therefore, for the intention-to-treat analyses, there were at delivery (table 1).

146 women in the antepartum dalteparin group and No participants were lost to follow-up during the

143 in the control group. However, 26 women crossed antepartum period or at labour and delivery. Five of

over within 10 days of randomisation (12 from dalteparin 146 women (3·4%) in the antepartum dalteparin group

to no dalteparin, and 14 from no dalteparin to dalteparin), were non-compliant with antepartum dalteparin (ie, they

and an additional five patients in the treatment group took <80% of the prescribed doses). In the post-partum

were non-compliant with antepartum dalteparin and period, non-compliance with post-partum dalteparin was

were excluded from on-treatment and safety analyses. similar between the groups (9·6% [14/146] in the

Therefore, there were 143 women on antepartum antepartum dalteparin group vs 9·8% [14/143] in the

dalteparin and 141 women on no antepartum dalteparin control group).

for the on-treatment and safety analyses (figure 1). Overall, 52 of 289 randomised women experienced one

The baseline characteristics of the two groups were or more components of the primary composite outcome

similar (table 1). Overall, the mean age of the women was measure (symptomatic major venous thromboembolism,

31·8 years (SD 4·9), mean gestational age at randomisation severe or early onset pre-eclampsia, birth of a small-for-

was 11·9 weeks (4·6), and most participants were white gestational-age infant [<10th percentile], or pregnancy

(91% [262/289]). Most women had either the factor V loss). 25 of 146 (17·1% [95% CI 11·4–24·2%]) had the

Leiden (60% [176/289]) or prothrombin gene mutation primary composite outcome in the antepartum dalteparin

(22% [63/289]). During a mean of 2·2 previous pregnancies group compared with 27 of 143 (18·9% [12·8–26·3]) in the

(SD 1·8) and a mean of 1·0 (1·0) previous deliveries, 61% no antepartum dalteparin group (p=0·70), with a difference

(176/289) of the study population had experienced of −1·8% in favour of dalteparin (95% CI of difference

pregnancy complications. 44% (128/289) of participants –10·6% to 7·1%) (table 2). None of the component

had a risk factor for venous thromboembolism, most of outcomes of the primary composite outcome measure

whom (79% [101/128]) had a first-degree relative with the differed between the two groups (table 2). There were also

disorder. During the study pregnancy, aspirin use was no between-group differences with alternate severity

slightly more common in the control group (difference definitions for these component outcomes (table 2). Three

+10·4% [95% CI −0·5% to 21·3%]) whereas analgesic use patients had symptomatic major venous thromboembolism

was slightly more frequent in the antepartum dalteparin while on dalteparin (two with previous calf deep vein

group (difference +11·6% [−0·4% to 22·8%]). thrombosis had venous thromboembolism during the

The proportions of patients undergoing a caesarean post-partum period and one patient with previous

section or experiencing peri-partum haemorrhage (a provoked proximal deep vein thrombosis and anti-

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 7

Articles

phospholipid antibodies had venous thromboembolism at mid-1990s led to widespread off-label use of low-molecular-

11 weeks’ gestation while on antepartum dalteparin). Mean weight heparin in pregnant women—both with and

birthweight and gestational age at delivery of livebirths without thrombophilia—who had previous pregnancy

were similar between the groups. complications. This off-label use has been fuelled by the

Our prespecified subgroup analyses showed no emotional consequences of these complications21

significant differences between groups in terms of combined with expert opinion,22,23 consensus panels,24,25

thrombophilia, previous pregnancy complications, and small non-randomised studies suggesting benefit.26–28

previous venous thromboembolism events or risk Antepartum low-molecular-weight herparin is not a

factors, aspirin use, gestational age at enrolment or benign intervention; it can be complicated by heparin-

country, in both intention–to-treat and on-treatment induced thrombocytopenia29,30 (albeit rarely), withholding

See Online for appendix analyses (table 2, figure 2, and appendix). of epidural analgesia, and, as shown in our trial, increased

Although we recorded no differences in major bleeding minor bleeding,14 allergic reactions,14 skin reactions,14 raised

events, more minor bleeding events occurred in the ante- liver transaminase concentrations, and the risk of

partum dalteparin group (19·6% [28/143]) than in the no induction of labour. Additionally, up to 400 subcutaneous

antepartum dalteparin group (9·2% [13/141]; p=0·01) injections of the drug per term of pregnancy is both a

(table 2). No patients had heparin-induced thrombo- personal and financial burden. Clinicians and patients can

cytopenia, changes in bone mineral density, or clinical be reassured that dalteparin use throughout the

fracture. antepartum period does not lead to significant changes in

One patient who received antepartum dalteparin had a bone mineral density. Finally, the continued belief in

left parieto-occipital transient ischaemic attack (expressive ineffective therapy hampers further research for efficacious

aphasia and right visual field loss for 1 h) at 27 weeks’ treatments for women at risk of venous thromboembolism

gestation with no thrombocytopenia. One participant in and pregnancy complications.

the control group had a severe allergic reaction (lip/ We designed the trial to detect a minimal clinically

tongue swelling) after a first dose of post-partum important difference of 16% in the composite primary

dalteparin. Allergic-type skin reactions were noted in outcome (severe or early-onset pre-eclampsia, small-for-

15 participants on dalteparin (nine antepartum and six gestational-age infants <10th percentile, pregnancy loss, or

post partum) and in four participants not on dalteparin major venous thromboembolism). This 16% absolute

(three antepartum and one post partum in a non- difference translates into a number needed to treat of six—

compliant participant). Raised levels of liver enzymes ie, six women would need to inject up to 400 needles per

(aspartate aminotransferase or alanine transaminase)— pregnancy at a drug cost of more than US$8000 per

defined as two-times normal values—were recorded in pregnancy to prevent one outcome. The lower bound of

11 participants on dalteparin (ten antepartum and one the 95% CI of the difference in composite event rates

post partum) and in none of the control participants. between groups in our intention-to-treat analysis (−1·8%

Three neonatal deaths occurred in infants born favouring dalteparin [95% CI of difference –10·6% to

prematurely. One of these deaths occurred in the 7·1%) and in our on-treatment analysis (+2·6% favouring

antepartum dalteparin group (preterm rupture of control [95% CI –6·4 to 11·6%]), excludes a 16% difference

membranes at 24 weeks’ gestation) and two were in the favouring dalteparin; therefore, we can conclude that

control group (preterm rupture of membranes at 24 weeks’ important treatment effects have been excluded. Although

gestation and pre-eclampsia at 30 weeks). Six children in our trial was not designed to detect important differences

pregnancies exposed to antepartum dalteparin had in each individual component of our composite outcome,

congenital anomalies (ankyloglossia [n=2], ectopic kidney, our secondary analyses do not support important treatment

trisomy, strawberry haemangioma, and cataract). Two effects in these outcomes. We noted that in the relevant

children in the control group had congenital anomalies subgroups of women with thrombophilia, such as those

(hemi-vertebrae/scoliosis and duplex renal collecting with previous pregnancy loss, previous pre-eclampsia,

system). previous birth of a small-for-gestational-age infant, and a

family history of venous thromboembolism, antepartum

Discussion dalteparin did not seem to reduce the risk of pregnancy

In our trial, antepartum dalteparin did not reduce the loss, placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, or

risk of either pregnancy loss, venous thromboembolism, venous thromboembolism. Although these secondary and

or placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution,

pregnant women with thrombophilia at high risk of they suggest that women with thrombophilia should not

pregnancy loss, venous thromboembolism, or placenta- be prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent

mediated pregnancy complications. these complications unless further research suggests

This trial addresses a key therapeutic question in a large benefit in these subgroups or individual outcomes.

and vulnerable patient group. The absence of benefit is an The strengths of our trial include its generalisability

important finding. The discovery of an association between provided by the multinational design, the strategies used

thrombophilia and pregnancy complications in the to protect against bias (including allocation concealment

8 www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5

Articles

from central web randomisation, masked independent

adjudication of all outcome events, and no loss of patients Panel 2: Research in context

to follow-up), and a dosing regimen that ensured Systematic review

prophylactic dose anti-factor Xa activity throughout We did a systematic review and meta-analysis following a systematic review protocol

pregnancy in most women.15 Our primary composite previously published39 and updated in January, 2014, to explore the benefit of

outcome measure included events that are all clinically low-molecular-weight heparin in preventing placenta-mediated pregnancy complications

important, and equal weighting of these events was judged and pregnancy loss. We also added the search terms “venous thrombosis”, “deep vein

appropriate by the investigators and grant reviewers a thrombosis”, and “pulmonary embolism” to explore the benefit of antepartum low-

priori. In view of the fact that women with thrombophilia molecular-weight heparin to prevent venous thromboembolism in thrombophilic women.

who have had previous complications seem to be at higher The latter search identified no trials. We assessed the quality of the evidence with the

risk of all of these complications in subsequent Cochrane Handbook’s risk of bias assessment tool.

pregnancies, and that these complications often overlap, to

study a composite outcome measure in this therapeutic Interpretation

area also seemed to be a sensible and pragmatic approach. Our findings are consistent with previously published high-quality evidence that suggests

Our trial has some limitations. Crossover and non- no benefit of antepartum low-molecular-weight heparin in women with previous

compliance might have led to a reduction in detectable pregnancy loss, women with previous non-severe or late-onset pre-eclampsia, or women

treatment effect. However, crossover was balanced, non- with previous small-for-gestational-age birth between the 5th and 10th percentile. Our

compliance was negligible (3·4% of participants randomised trial is the first to show that thrombophilic women without previous venous

administered <80% of antepartum dalteparin doses), and thrombosis do not benefit from antepartum low-molecular-weight-heparin. Our meta-

our on-treatment sensitivity analysis did not change the analysis shows that lower quality evidence suggests that low-molecular-weight heparin

conclusions of the study. Recruitment challenges led to might prevent recurrent severe placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (severe or

the trial being completed after more than 12 years of early-onset pre-eclampsia, small-for–gestational-age birth <5th percentile, and placental

enrolment and introduce the possibility of time trend or abruption) but we did not record this benefit in the subgroup analyses of our trial.

cohort effects. The characteristics of participants, co-

interventions, or both, might have varied over time and thromboembolism in our trial had a history of calf deep

led to changes in participants’ risk for outcomes. A vein thrombosis or provoked venous thromboembolism.

plausible notion is that the combination of dalteparin with All three women had venous thromboembolism while on

aspirin is effective whereas dalteparin alone is not prophylactic dalteparin (one antepartum and two post-

effective. Indeed, in our subgroup analysis in aspirin partum), and the overall event rate was 3 of 36 (8·3%;

users, antepartum dalteparin trended toward a treatment 95% CI 1·7–22·5%) in the subgroup with previous calf

effect but did not reach significance. Ideally, all patients deep vein thrombosis or previous provoked venous

would have been randomised in early pregnancy to thromboembolism. This finding suggests that these

maximise the possibility that dalteparin could positively patients might need more aggressive prophylaxis.13

affect placental development. Our subgroup analysis of Our subgroup analysis in women with thrombophilia

treatment effect by gestational age at enrolment did not and previous pregnancy loss suggesting no improvement

suggest differential effect but had low power to explore in livebirth rate with low-molecular-weight heparin is

this hypothesis. Future research into higher doses of low- consistent with other multicentre trials that have shown no

molecular-weight heparin with and without aspirin, or increase in livebirth rate with this treatment in unselected

trials that start treatment with low-molecular-weight patients,31–34 women without thrombophilia,34 and in

heparin earlier in pregnancy, might be warranted. women with thrombophilia.35 This finding contrasts with

Our findings need to be considered in the context of the results of three single-centre trials, with a higher risk of

previous trials exploring the benefit of low-molecular- bias, suggesting benefit in women with thrombophilia36

weight heparin to prevent pregnancy-associated venous and without thrombophilia.37,38 Overall, the existing

thromboembolism, recurrent pregnancy loss, and late evidence does not support the use of low-molecular-weight

placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. Our study is heparin to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss.

the first randomised trial to assess the risks and benefits of To analyse the cumulative evidence assessing the use of

low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent pregnancy- low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent recurrent late

associated venous thromboembolism in women with placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (late

thrombophilia (panel 2). None of the pregnant women pregnancy loss, pre-eclampsia, abruption, or small-for-

with thrombophilia without previous distal or provoked gestational-age infants <10th percentile), we updated our

venous thromboembolism had symptomatic major recently published meta-analysis39 with our present

antepartum venous thromboembolism in the control findings (figure 3). This updated meta-analysis suggests a

group (0%, 95% CI 0–2·8%). This result affirms consensus benefit in reducing recurrent late placenta-mediated

guidelines that suggest that women with thrombophilia complications (RR 0·57, 95% CI 0·36–0·91) but showed

without previous venous thromboembolism can have substantial heterogeneity (I²=68%). We did subgroup

antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis withheld.13 analyses to assess the causes of this heterogeneity. When

However, all three women who had venous we explored the summary effects and heterogeneity in

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 9

Articles

multicentre trials,40–42 including TIPPS (RR 0·86 [95% CI complications, or venous thrombosis does not reduce the

0·53–1·41]; I²=47%) compared with single-centre trials43–45 occurrence of these complications. Further research is

(0·36 [0·24–0·52]; I²=0%), we noted a reduction in overall needed to establish whether low-molecular-weight heparin

heterogeneity and no clear treatment effect from the reduces the risk of recurrent severe pre-eclampsia,

results of multicentre trials. When we explored trials severely small-for-gestational-age infants (birthweight

registered in a clinical trials registry before completion,40,42 <5th percentile), or placental abruption.

including TIPPS (RR 1·08 [95% CI 0·74–1·60]; I²=0%) Contributors

compared with trials not registered before completion41,43–45 MAR and PSW participated in study design, data collection and

(0·35 [0·25–0·50]; I²=0%), we also noted an important interpretation, writing and critical review of the report, and approval of

the final version. WMH, JK, SRK, AK, EK, and MW participated in study

reduction in heterogeneity and no clear treatment effect design, data collection, critical review of the report, and approval of the

in registered trials. Conversely, when we analysed trials final version. DF* and TR* contributed to study design, data analysis, data

that included only women with previous severe late interpretation, critical review of the report, and approval of the final

placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, at a study version. AMC and GLG participated in data collection, data analysis, data

interpretation, writing and critical review of the report, and approval of

level41,44,45 (RR 0·37 [95% CI 0·25–0·55]; I²=0%) compared the final version. RM participated in data analysis and interpretation,

with trials that included women with previous non-severe critical review of the report, and approval of the final version. MS, SC,

late placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, at a WSC, JS, ER, SR, RK, CD, MJK, SS, KH, JD, GS, SM, JN-A, AM, MK,

study level,40,42,43 including TIPPS (RR 0·80 [95% CI RMS, IAG, KR-M, BM*, NT*, JM*, LO*, MB*, WF*, LM*, PvD*, MP*,

MC*, HC*, PC*, AT*, CC*, and SM* participated in data collection,

0·44–1·46]; I²=68%), we also noted a reduction in critical review of the report, and approval of the final version. CN*

heterogeneity and no clear treatment effect in trials (deceased), PG* (deceased), and RL* (deceased) participated in study

including women with non-severe late placenta-mediated design and data collection. *Denotes members of the TIPPS investigators

pregnancy complications. In summary, higher quality not listed in main author list.

evidence suggests that low-molecular-weight heparin The TIPPS investigators

does not prevent recurrent non-severe placenta-mediated M A Rodger, W M Hague, J Kingdom, S R Kahn, A Karovitch, M Sermer,

A M Clement, S Coat, W S Chan, J Said, E Rey, S Robinson, R Khurana,

pregnancy complications, whereas lower quality evidence C Demers, M J Kovacs, S Solymoss, K Hinshaw, J Dwyer, G Smith,

suggests that low-molecular-weight heparin might S McDonald, J Newstead-Angel, A McLeod, M Khandelwal, R Silver,

prevent recurrent severe placenta-mediated pregnancy G Le Gal, I A Greer, E Keely, K Rosene-Montella, M Walker, P S Wells,

B McCarron, N Thomas, J Martel, C Nimrod (deceased), L Opatrny,

complications. However, given that the latter evidence is

M Blostein, L Magee, P von Dadelszen, M Carrier, R Mallick, T Ramsay,

mainly driven by single-centre unregistered trials, the E Pasquier, D Fergusson, and M Paidas. Data Safety Monitoring Board:

quality of evidence dictates that further research is needed M Cushman (Chair 2007–12), H Clark (Chair 2003–06), P Garner

to explore this hypothesis. Meanwhile, women with and (deceased) (Chair 2000–02), R Lee (deceased), P Callas, A Tinmouth,

C Code, and S McFaul.

without thrombophilia, with previous late-onset and non-

severe pre-eclampsia and previous mildly small-for- Declaration of interests

AM has received honoraria for educational activities from Leo Pharma,

gestational-age infants (birthweight between 5th and 10th

Sanofi, and Bayer. The other authors declare no competing interests.

percentile) should not be offered low-molecular-weight

Acknowledgments

heparin to prevent recurrent pregnancy complications. This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research

In conclusion, antepartum prophylactic dose (MCT 82205) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (NA 4849).

dalteparin in women with thrombophilia at increased risk Partial start-up funding (US$150 000) and initial study drug were provided

of pregnancy loss, placenta-mediated pregnancy by Pharmacia and UpJohn (2000–02). MR was supported by a Heart and

Stroke Foundation of Ontario Career Investigator Award (CI6225 and

CI7441) and a University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research

Relative risk Chair in Venous Thrombosis and Thrombophilia. SRK is supported by a

(95% CI)

National Research Scientist award from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé

Rey et al (2009) 0·35 (0·15–0·79) du Québec. SM is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Gris et al (2010) 0·39 (0·21–0·68) New Investigator Award. JK was supported by the Rose Torno Chair.

Gris et al (2011) 0·36 (0·18–0·69) References

Mello et al (2005) 0·30 (0·14–0·60) 1 Rodeghiero F, Tosetto A. The epidemiology of inherited

Martinelli et al (2012) 1·10 (0·55–2·21) thrombophilia: the VITA Project. Vicenza Thrombophilia and

Atherosclerosis Project. Thromb Haemost 1997; 78: 636–40.

de Vries et al (2012) 1·10 (0·63–1·93)

2 Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR,

Rodger et al (2014) 1·05 (0·50–2·25) Melton LJ 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism

Combined (random effects) 0·57 (0·36–0·91) during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study.

Ann Intern Med 2005; 143: 697–706.

0·1 0·2 0·5 1 2 5 3 Gerhardt A, Scharf RE, Beckmann MW, et al. Prothrombin and

Relative risk (95% CI) factor V mutations in women with a history of thrombosis during

pregnancy and the puerperium. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 374–80.

Figure 3: Meta-analysis of published randomised trials assessing the relative risk reduction (random effects) 4 Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related

of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications with low-molecular-weight heparin in women mortality in the United States, 1987–1990. Obstet Gynecol 1996;

with previous placenta-mediated pregnancy complications 88: 161–67.

Recurrent placenta-mediated complications were defined as any pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, birth of a 5 Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Causes of

small-for-gestational-age infant (birthweight <10th percentile), or pregnancy loss at more than 20 weeks. death among stillbirths. JAMA 2011; 306: 2459–68.

Previous placenta-mediated complications were pre-eclampsia, birth of a small-for-gestational-age infant 6 van Rijn BB, Hoeks LB, Bots ML, Franx A, Bruinse HW. Outcomes

(birthweight <10th percentile), late pregnancy loss (>12 weeks), or placental abruption. of subsequent pregnancy after first pregnancy with early-onset

preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 195: 723–28.

10 www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5

Articles

7 van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Cohn A, Katib Y, Walker M, 27 Grandone E, Brancaccio V, Colaizzo D, et al. Preventing adverse

Rodger MA. Risk of subsequent thromboembolism for patients obstetric outcomes in women with genetic thrombophilia.

with pre-eclampsia. BMJ 2003; 326: 791–92. Fertil Steril 2002; 78: 371–75.

8 Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Ante- and postnatal risk 28 Kupferminc MJ, Fait G, Many A, et al. Low-molecular-weight

factors of venous thrombosis: a hospital-based case-control study. heparin for the prevention of obstetric complications in women

J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6: 905–12. with thrombophilias. Hypertens Pregnancy 2001; 20: 35–44.

9 Pabinger I, Grafenhofer H, Kaider A, et al. Preeclampsia and fetal 29 Huhle G, Geberth M, Hoffmann U, Heene DL, Harenberg J.

loss in women with a history of venous thromboembolism. Management of heparin-associated thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21: 874–79. with subcutaneous r-hirudin. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2000; 49: 67–69.

10 Rodger MA, Betancourt MT, Clark P, et al. The association of factor 30 Lepercq J, Conard J, Borel-Derlon A, et al. Venous

V leiden and prothrombin gene mutation and placenta-mediated thromboembolism during pregnancy: a retrospective study of

pregnancy complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of enoxaparin safety in 624 pregnancies. BJOG 2001; 108: 1134–40.

prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med 2010; 7: e1000292. 31 Visser J, Ulander VM, Helmerhorst FM, et al. Thromboprophylaxis

11 Rey E, Kahn SR, David M, Shrier I. Thrombophilic disorders and for recurrent miscarriage in women with or without thrombophilia.

fetal loss: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 361: 901–08. HABENOX: a randomised multicentre trial. Thromb Haemost 2011;

12 Kupferminc MJ, Eldor A, Steinman N, et al. Increased frequency of 105: 295–301.

genetic thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. 32 Kaandorp SP, Goddijn M, van der Post JA, et al. Aspirin plus

N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 9–13. heparin or aspirin alone in women with recurrent miscarriage.

13 Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1586–96.

Vandvik PO. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and 33 Clark P, Walker ID, Langhorne P, et al, and the Scottish Pregnancy

pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, Intervention Study (SPIN) collaborators. SPIN (Scottish Pregnancy

9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Intervention) study: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial of

Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141 (2 suppl): e691S–736S. low-molecular-weight heparin and low-dose aspirin in women with

14 Greer IA, Nelson-Piercy C. Low-molecular-weight heparins for recurrent miscarriage. Blood 2010; 115: 4162–67.

thromboprophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in 34 Dolitzky M, Inbal A, Segal Y, Weiss A, Brenner B, Carp H.

pregnancy: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. Blood 2005; A randomized study of thromboprophylaxis in women with

106: 401–07. unexplained consecutive recurrent miscarriages. Fertil Steril 2006;

15 Hunt BJ, Doughty HA, Majumdar G, et al. Thromboprophylaxis 86: 362–66.

with low molecular weight heparin (Fragmin) in high risk 35 Laskin CA, Spitzer KA, Clark CA, et al. Low molecular weight

pregnancies. Thromb Haemost 1997; 77: 39–43. heparin and aspirin for recurrent pregnancy loss: results from the

16 Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al, and the Fetal/Infant Health randomized, controlled HepASA Trial. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 279–87.

Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A new 36 Gris J-C, Mercier E, Quéré I, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin

and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight versus low-dose aspirin in women with one fetal loss and a

for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001; 108: E35. constitutional thrombophilic disorder. Blood 2004; 103: 3695–99.

17 Schulman S, Kearon C, and the Subcommittee on Control of 37 Fawzy M, Shokeir T, El-Tatongy M, Warda O, El-Refaiey AA,

Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of Mosbah A. Treatment options and pregnancy outcome in women

the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage: a randomized placebo-

Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of controlled study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008; 278: 33–38.

antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. 38 Badawy AM, Khiary M, Sherif LS, Hassan M, Ragab A, Abdelall I.

J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 692–94. Low-molecular weight heparin in patients with recurrent early

18 Friederich PW, Sanson BJ, Simioni P, et al. Frequency of miscarriages of unknown aetiology. J Obstet Gynaecol 2008; 28: 280–84.

pregnancy-related venous thromboembolism in anticoagulant 39 Rodger MA, Carrier M, Le Gal G, et al, and the Low-Molecular-

factor-deficient women: implications for prophylaxis. Weight Heparin for Placenta-Mediated Pregnancy Complications

Ann Intern Med 1996; 125: 955–60. Study Group. Meta-analysis of low-molecular-weight heparin to

19 Lie RT, Rasmussen S, Brunborg H, Gjessing HK, Lie-Nielsen E, prevent recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications.

Irgens LM. Fetal and maternal contributions to risk of pre- Blood 2014; 123: 822–28.

eclampsia: population based study. BMJ 1998; 316: 1343–47. 40 de Vries JIP, van Pampus MG, Hague WM, Bezemer PD,

20 Sibai BM, Ewell M, Levine RJ, et al, and the The Calcium for Joosten JH, and the FRUIT Investigators. Low-molecular-weight

Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) Study Group. Risk factors heparin added to aspirin in the prevention of recurrent early-onset

associated with preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women. pre-eclampsia in women with inheritable thrombophilia: the

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177: 1003–10. FRUIT-RCT. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10: 64–72.

21 Rodger MA, Makropoulos D, Walker M, Keely E, Karovitch A, 41 Rey E, Garneau P, David M, et al. Dalteparin for the prevention of

Wells PS. Participation of pregnant women in clinical trials: will recurrence of placental-mediated complications of pregnancy in

they participate and why? Am J Perinatol 2003; 20: 69–76. women without thrombophilia: a pilot randomized controlled trial.

22 Brenner B. Antithrombotic prophylaxis for women with J Thromb Haemost 2009; 7: 58–64.

thrombophilia and pregnancy complications—Yes. 42 Martinelli I, Ruggenenti P, Cetin I, et al, and the HAPPY Study

J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1: 2070–72. Group. Heparin in pregnant women with previous placenta-

23 Lockwood CJ. Inherited thrombophilias in pregnant patients: mediated pregnancy complications: a prospective, randomized,

detection and treatment paradigm. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 99: 333–41. multicenter, controlled clinical trial. Blood 2012; 119: 3269–75.

24 Duhl AJ, Paidas MJ, Ural SH, et al. Antithrombotic therapy and 43 Mello G, Parretti E, Fatini C, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin

pregnancy: consensus report and recommendations for prevention lowers the recurrence rate of preeclampsia and restores the

and treatment of venous thromboembolism and adverse pregnancy physiological vascular changes in angiotensin-converting enzyme

outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; 197: 457.e1–.e21. DD women. Hypertension 2005; 45: 86–91.

25 Lussana F, Dentali F, Abbate R, et al, and the Italian Society for 44 Gris JC, Chauleur C, Molinari N, et al. Addition of enoxaparin to

Haemostasis and Thrombosis. Screening for thrombophilia and aspirin for the secondary prevention of placental vascular

antithrombotic prophylaxis in pregnancy: Guidelines of the Italian complications in women with severe pre-eclampsia. The pilot

Society for Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET). Thromb Res 2009; randomised controlled NOH-PE trial. Thromb Haemost 2011;

124: e19–25. 106: 1053–61.

26 Brenner B, Hoffman R, Carp H, Dulitsky M, Younis J, and the 45 Gris JC, Chauleur C, Faillie JL, et al. Enoxaparin for the secondary

LIVE-ENOX Investigators. Efficacy and safety of two doses of prevention of placental vascular complications in women with

enoxaparin in women with thrombophilia and recurrent pregnancy abruptio placentae. The pilot randomised controlled NOH-AP trial.

loss: the LIVE-ENOX study. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 227–29. Thromb Haemost 2010; 104: 771–79.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5 11

Comment

TIPPing practice away from anticoagulation in pregnancy

Clinical management of women with a history of adverse comprised the composite primary outcome (severe or

pregnancy outcomes (ie, recurrent early pregnancy early-onset pre-eclampsia, small-for-gestational-age

loss, severe pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, and infants [<10th percentile], pregnancy loss, or venous

unexplained fetal growth restriction or stillbirth) is a thromboembolism); in both intention-to-treat and on-

challenging area in obstetrics because of the paucity treatment analyses; and across pre-planned subgroup

of evidence-based preventive therapies. In the face analyses. From a patient safety perspective, although

Science Photo Library

of emotionally charged requests for preventive treat- no differences in major bleeding or bone mineral density

ment by women with adverse pregnancy outcomes, were recorded, dalteparin was associated with an

clinicians are often tempted to provide non-evidence- increase in minor bleeding, abnormal liver enzymes, and

based therapies that might seem to be both biologically local skin reactions. Published Online

July 25, 2014

plausible and of minimum harm. The TIPPS study design was methodologically http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

In the 1990s, epidemiological data emerged showing an rigorous. The investigators used pragmatic eligibility S0140-6736(14)60850-3

association between genetic thrombophilias and adverse criteria (which make the results broadly generalisable See Articles

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

pregnancy outcomes.1,2 The proposed pathophysiological to pregnant women with thrombophilias), event S0140-6736(14)60793-5

mechanism linking maternal prothrombotic tendencies adjudication was masked, there was no loss to follow-

with adverse pregnancy outcomes is through placental up for the primary outcome, participant adherence to

insufficiency caused by microvascular or macrovascular dalteparin was high, and crossover rates were similar

thrombosis of this crucial maternal–fetal interface. This in the two study groups. The study limitations include

concept led researchers to investigate low-molecular- the low event rates (18·9% events observed vs 49%

weight heparin as a potential treatment to reduce anticipated in the control group), differential use of

placental thrombosis and thereby reduce adverse aspirin between the study groups, slow recruitment

pregnancy outcomes. Early studies showed promising rate, and the small subgroup sizes. However, several

results3,4 and, despite the absence of high-quality important points should be noted. First, the lower than

evidence, clinicians and guideline committees5 quickly anticipated event rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes

adopted use of these drugs. However, subsequent higher is consistent with recent prospective observational data

quality randomised clinical trials6,7 were unable to replicate showing lower (and often non-significant) associations

the success of earlier research. between thrombophilias and adverse pregnancy

The Thrombophilia in Pregnancy Prophylaxis Study outcomes.9 The difference in event rates in TIPPS still

(TIPPS),8 undertaken by Marc Rodger and colleagues reliably excludes the trial’s prespecified minimally

and reported in The Lancet, is the first large international clinically significant difference of 16% (ie, resulting in a

randomised controlled trial designed to resolve the number needed to treat of six).

clinical equipoise of the effect of antepartum low- Second, the rate of aspirin use was higher in the

molecular-weight heparin (dalteparin) on adverse non-dalteparin group (40%) than in the dalteparin

pregnancy outcomes in women at the highest risk of group (30%), especially in women with previous pre-

these outcomes (ie, women with both thrombophilia eclampsia or small-for-gestational-age infants (68%

and a history of either adverse pregnancy outcomes or control vs 41% dalteparin). This finding probably

venous thromboembolism). The results of this study represents the clinicians’ perceived need to intervene

are convincingly negative: following randomisation (because the study was unmasked), but aspirin use is

of 292 women, antepartum dalteparin did not unlikely to have significantly biased the trial results,

significantly reduce the incidence of adverse pregnancy since other large studies have not shown a benefit of

outcomes, the trial’s primary outcome, recorded in aspirin in reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes10,11

25 of 146 women (17·1%) in the dalteparin group versus apart from a minor reduction in pre-eclampsia.12

27 of 143 (18·9%) in the control group (risk difference Third, although the 12-year recruitment period was

–1·8%, 95% CI –10·6 to 7·1). The results were consistent extremely long, treatments for prevention of adverse

across the wide range of clinically important events that pregnancy outcomes did not change substantially

www.thelancet.com Published online July 25, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60850-3 1

Comment

during this period. Fourth, despite the small subgroup *Paul S Gibson, Kara A Nerenberg

sizes, TIPPS showed no statistically significant benefit Departments of Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynecology,

University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, T3L 2Y3, Canada (PSG); and

across any of these subgroups, which is consistent

The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa,

with the investigators’ updated systematic review Ottawa, ON, Canada (KAN)

and meta-analysis.8 Finally, caution should be used in gibsonp@ucalgary.ca

interpretation of the subgroup analysis that showed PSG receives an unrestricted educational grant from Sanofi. KN declares no

an apparent non-significant benefit of low-molecular- competing interests.

1 Kupferminc MJ, Eldor A, Steinman N, et al. Increased frequency of genetic

weight heparin in patients who used aspirin, in view of thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. N Engl J Med

the high number of subgroups compared and the small 1999; 340: 9–13.

2 Rey E, Kahn SR, David M, Shrier I. Thrombophilic disorders and fetal loss:

subgroup size. Nonetheless, this latter finding might a meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 361: 901–08.

merit further research. 3 Gris JC, Mercier E, Quéré I, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus

low-dose aspirin in women with one fetal loss and a constitutional

TIPPS emphasises other important messages for thrombophilic disorder. Blood 2004; 103: 3695–99.

clinicians and researchers. Despite vigorous recruitment 4 Brenner B, Hoffman R, Carp H, Dulitsky M, Younis J. Efficacy and safety of

two doses of enoxaparin in women with thrombophilia and recurrent

efforts, it took more than 12 years to recruit 292 women pregnancy loss: the LIVE-ENOX study. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 227–29.

at 36 centres in five countries. 15 centres did not recruit 5 Bates SM, Greer IA, Hirsh J, Ginsberg JS. Use of antithrombotic agents

during pregnancy: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and

any participants at all, mainly because the use of low- Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004; 126: 627S–44S.

6 de Vries JIP, van Pampus MG, Hague WM, Bezemer PD, Joosten JH. Low-

molecular-weight heparin had already become local molecular-weight heparin added to aspirin in the prevention of recurrent

standard practice. This situation draws attention to the early-onset pre-eclampsia in women with inheritable thrombophilia: the

FRUIT-RCT. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10: 64–72.

fact that clinicians’ altruistic intentions to treat these 7 Martinelli I, Ruggenenti P, Cetin I, et al. Heparin in pregnant women with

high-risk women might have inadvertently caused them previous placenta-mediated pregnancy complications: a prospective,

randomized, multicenter, controlled clinical trial. Blood 2012;

minor harm, potentially increased the rates of labour 119: 3269–75.

induction, reduced access to regional anaesthetics, 8 Rodger MA, Hague WM, Kingdom J, et al. Antepartum dalteparin versus no

antepartum dalteparin for the prevention of pregnancy complications in

increased health-care costs (because of the high cost of pregnant women with thrombophilia (TIPPS): a multinational open-label

randomised trial. Lancet 2014; published online July 25. http://dx.doi.

low-molecular-weight heparin), and slowed the research org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60793-5.

momentum in this area. Importantly, TIPPS also shows 9 Rodger MA, Betancourt MT, Clark P, et al. The association of factor V Leiden

and prothrombin gene mutation and placenta-mediated pregnancy

that withholding of antepartum low-molecular- complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective

cohort studies. PLoS Med 2010; 7: e1000292.