Professional Documents

Culture Documents

File 10

Uploaded by

My AccountCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

File 10

Uploaded by

My AccountCopyright:

Available Formats

24 CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF A MORPHEMIC KIND

that allomorphs are forms that are phonologically distinguishable which, none the less, are not functionally

distinct. In other words, although they are physically distinct morphs with different pronunciations, allomorphs

do share the same function in the language.

An analogy might help to clarify this point. Let us compare allomorphs to workers who share the same

job. Imagine a jobshare situation where Mrs Jones teaches maths to form 2DY on Monday afternoons, Mr Kato

on Thursday mornings and Ms Smith on Tuesdays and Fridays. Obviously, these teachers are different

individuals. But they all share the role of 'maths teacher' for the class and each teacher only performs that role on

particular days. Likewise, all allomorphs share the same function but one allomorph cannot occupy a position that

is already occupied by another allomorph of the same morpheme. To summarise, we say that allomorphs of a

morpheme are in complementary distribution. This means that they cannot substitute for each other. Hence, we

cannot replace one allomorph of a morpheme by another allomorph of that morpheme and change meaning.

For our next example of allomorphs we will turn to the plural morpheme. The idea of 'more than one' is

expressed by the plural morpheme using a variety of allomorphs including the following:

[13.8]

Singular Plural

a. rad-ius radi-i

cactus cact-i

b. dat-um dat-a

strat-um strat-a

c. analys-is analys-ex

ax-is ax-es

d. skirt skirt-s

road road-s

branch branch-es

Going by the orthography, we can identify the allomorphs -i, -a, -es and -s. The last is by far the

commonest: see section (7.3).

Try and say the batch of words in [3.8d] aloud. You will observe that the pronunciation of the plural

allomorph in these words is variable. It is [s] in skirts, [z] in roads and [Iz] (or for some speakers [ez]) in branches.

What is interesting about these words is that the selection of the allomorph that represents the plural is determined

by the last sound in the noun to which the plural morpheme is appended. We will return to this in more depth in

section (5.2).

We have already seen, that because allomorphs cannot substitute for each other, we never have two

sentences with different meanings which solely differ in that one sentence has allomorph X in a slot where another

sentence has allomorph Y. Compare the two sentences in [3.9]:

[3.9]

a. They have two cats b. They have two dogs

[el hæv tu: kæt-s] [el hæv tu: dg-z]

*[el hæv tu: kæt-z] *[el hæv tu: dg-s]

You might also like

- Linear B Lexicon PDFDocument149 pagesLinear B Lexicon PDFStavros KonhilasNo ratings yet

- Peace Corps Uzbek Language Competencies PDFDocument214 pagesPeace Corps Uzbek Language Competencies PDFAgustinusWibowoNo ratings yet

- Georgian SyntaxDocument11 pagesGeorgian Syntaxapi-247314087No ratings yet

- Keywords. Lexeme, WFRS, Deverbal Nouns, Clipping, Delocutive AdverbsDocument20 pagesKeywords. Lexeme, WFRS, Deverbal Nouns, Clipping, Delocutive AdverbsSaniago DakhiNo ratings yet

- Understanding Morphology Second EditionDocument14 pagesUnderstanding Morphology Second EditionJulia TamNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument43 pagesMorphologyالاستاذ محمد زغير100% (1)

- 5 Second Rule Game IdeasDocument1 page5 Second Rule Game IdeasJu Peixoto100% (1)

- How To Conjugate Magic Verb FAIRE in French + ExpressionsDocument4 pagesHow To Conjugate Magic Verb FAIRE in French + ExpressionsIrs DeveloperNo ratings yet

- Kurmanji BasicDocument30 pagesKurmanji BasicCarlos Alberto Ruiz Cuéllar100% (3)

- 2nd Quarter Journalism 7 & 8Document4 pages2nd Quarter Journalism 7 & 8tranie100% (1)

- Sarf Made Easy-Part 2Document18 pagesSarf Made Easy-Part 2Azhar Aziz100% (1)

- Basic Sentence Parts and PatternsDocument34 pagesBasic Sentence Parts and Patternsapi-327193447100% (1)

- Conant 1912 The Pepet Law in Philippine LanguagesDocument34 pagesConant 1912 The Pepet Law in Philippine LanguagesSCHWARZDYLE ZAMORASNo ratings yet

- 5 Mi Mundo - Guia - Preguntas y Respuestas ExamenDocument20 pages5 Mi Mundo - Guia - Preguntas y Respuestas ExamenHectorGalindo100% (1)

- 1962 Halle Phonology in Generative GrammarDocument20 pages1962 Halle Phonology in Generative Grammarфцв віфNo ratings yet

- Eng.15 Course OutlineDocument4 pagesEng.15 Course OutlineChristy Maximarie Espacio100% (1)

- Gawain 6 Pagsasalin NG TayutayDocument3 pagesGawain 6 Pagsasalin NG TayutayRossana Bongcato100% (1)

- Grammatical Relations and Semantic RolesDocument8 pagesGrammatical Relations and Semantic Rolesandreea_roman29100% (1)

- A Course Module For Life and Work of RizalDocument4 pagesA Course Module For Life and Work of RizalJonnabel MasinopaNo ratings yet

- The Translation of Serious Literature & Authoritative Statements - Poetry - Patricia Iris v. RazonDocument20 pagesThe Translation of Serious Literature & Authoritative Statements - Poetry - Patricia Iris v. RazonPatricia Iris Villafuerte RazonNo ratings yet

- AdequacyDocument3 pagesAdequacySumeyya Sarica100% (1)

- Chavacano LegendsDocument3 pagesChavacano LegendsjenNo ratings yet

- SALAMAT - Lyrics PDFDocument2 pagesSALAMAT - Lyrics PDFAhlee MagatNo ratings yet

- FIL. 173 Mga TerminoDocument6 pagesFIL. 173 Mga TerminoLORINILLE BATCHINITCHANo ratings yet

- Stylistic Semasiology of The English LanguageDocument9 pagesStylistic Semasiology of The English LanguageОленка ОлійникNo ratings yet

- PANANAW NG May-AkdaDocument1 pagePANANAW NG May-AkdaJing BanasNo ratings yet

- MetatesisDocument3 pagesMetatesisArls Paler PiaNo ratings yet

- Revised Bloo M's TaxonomyDocument29 pagesRevised Bloo M's TaxonomyJAKELESTER BANGCASANNo ratings yet

- Struktur Sintaktik Noam ChomskyDocument14 pagesStruktur Sintaktik Noam ChomskyNana DianaNo ratings yet

- Page 24Document1 pagePage 24JERALD HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- 24 Close EncoynterDocument2 pages24 Close EncoynterMelissa Jean BayobayNo ratings yet

- Singular Plural Gloss: Ɣar/ Imɣar-N, Investigating TheDocument14 pagesSingular Plural Gloss: Ɣar/ Imɣar-N, Investigating Theرضا محمد رضاNo ratings yet

- Moroccan Arabic plural formation analyzed through prosodic morphologyDocument28 pagesMoroccan Arabic plural formation analyzed through prosodic morphologyDjurdjaPavlovic100% (1)

- HASPELMATH_padroes de alinhamentoDocument26 pagesHASPELMATH_padroes de alinhamentoFrida LobatoNo ratings yet

- -μι verbs: I. Quick Overview and ReassuranceDocument4 pages-μι verbs: I. Quick Overview and ReassuranceRoniePétersonL.SilvaNo ratings yet

- Exercises Catalan&JavaneseDocument11 pagesExercises Catalan&JavaneseMeylin OsegueraNo ratings yet

- Group 8 MorphoDocument12 pagesGroup 8 MorphoRedzky RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Gramática Sección 3 Reading GreekDocument16 pagesGramática Sección 3 Reading GreekagustinaNo ratings yet

- Allo Morph 1Document4 pagesAllo Morph 1Wan Nurhidayati Wan JohariNo ratings yet

- Group 7 MorphoDocument12 pagesGroup 7 MorphoRedzky RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- QC2 4B NotesDocument4 pagesQC2 4B NoteswillwillwillwillwillwillNo ratings yet

- (2011) WHEELER, Max W. - The Evolution of A Morphome in Catalan Verb InectionDocument29 pages(2011) WHEELER, Max W. - The Evolution of A Morphome in Catalan Verb InectionpradoNo ratings yet

- Intro Lecture 10Document30 pagesIntro Lecture 10Jana SaadNo ratings yet

- Chaha (Gurage) MorphologyDocument61 pagesChaha (Gurage) MorphologyNagendra ModeNo ratings yet

- Class 21 AllomorphyDocument13 pagesClass 21 AllomorphyThuận Ngô HùngNo ratings yet

- Spanning: Peter Svenonius CASTL, University of Tromsø April 25, 2012Document17 pagesSpanning: Peter Svenonius CASTL, University of Tromsø April 25, 2012Francesco-Alessio UrsiniNo ratings yet

- Biber Et Al 2021 - NumberDocument8 pagesBiber Et Al 2021 - NumberОлександра КоротченкоNo ratings yet

- X-Bar Theory, 2021Document9 pagesX-Bar Theory, 2021Sara Belemkaddem100% (1)

- 650 Boudlal 5 0Document45 pages650 Boudlal 5 0JekillNo ratings yet

- Morphological Analysis and Generation of Arabic Nouns: A Morphemic Functional ApproachDocument8 pagesMorphological Analysis and Generation of Arabic Nouns: A Morphemic Functional ApproachzakloochNo ratings yet

- G. Rappaport: Grammatical Role of Animacy in A Formal Model of Slavic MorphologyDocument28 pagesG. Rappaport: Grammatical Role of Animacy in A Formal Model of Slavic Morphologyanon_315959073No ratings yet

- Contrastive analysis of English consonant phonemesDocument63 pagesContrastive analysis of English consonant phonemes손유림No ratings yet

- Summary of Words and Its Forms: InflectionalDocument4 pagesSummary of Words and Its Forms: Inflectionalhapsari mutyaNo ratings yet

- 0 A Unified Account of The Tagalog Verb PDFDocument16 pages0 A Unified Account of The Tagalog Verb PDFJim100% (1)

- Introductory Concepts 1Document8 pagesIntroductory Concepts 1mostarjelicaNo ratings yet

- Fossil Nominalization Prefixes in TibetaDocument18 pagesFossil Nominalization Prefixes in TibetaJason Phlip NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- Metrical Patterns PDFDocument5 pagesMetrical Patterns PDFAlcel PascualNo ratings yet

- Word StemDocument3 pagesWord StemRommelBaldagoNo ratings yet

- 01IntroProsodicHierarchy PDFDocument12 pages01IntroProsodicHierarchy PDFPaula Pinheiro CostaNo ratings yet

- Prepositions of Location: At, In, OnDocument8 pagesPrepositions of Location: At, In, OnIgor MatsuoNo ratings yet

- LexiconDocument848 pagesLexiconAnna Pazsint100% (1)

- Butskhrikidze, Marika, and Jeroen Van de Weijer - On V-Metathesis in Modern Georgian (2001)Document11 pagesButskhrikidze, Marika, and Jeroen Van de Weijer - On V-Metathesis in Modern Georgian (2001)Dominik K. CagaraNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Sound Pairs Minimal PairDocument5 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Sound Pairs Minimal PairERFIN SUGIONONo ratings yet

- Jamison Casedisharmonygvedic 1982Document22 pagesJamison Casedisharmonygvedic 1982nishaNo ratings yet

- Morpheme Identification PrinciplesDocument6 pagesMorpheme Identification PrinciplesB19 JarNo ratings yet

- ExercisesDocument9 pagesExercisesJo SantosNo ratings yet

- TSL3104 Aspects of Connected SpeechDocument19 pagesTSL3104 Aspects of Connected SpeechSuhaniya Mahendran100% (1)

- Intervals: I. Word ListDocument32 pagesIntervals: I. Word ListfedericoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledMy AccountNo ratings yet

- Introduction to the Study of WordsDocument1 pageIntroduction to the Study of WordsMy AccountNo ratings yet

- File 11Document1 pageFile 11My AccountNo ratings yet

- Master social skills and etiquette with this presentationDocument16 pagesMaster social skills and etiquette with this presentationAjay MallavarapuNo ratings yet

- File 1Document1 pageFile 1My AccountNo ratings yet

- Electronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsDocument9 pagesElectronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsMy AccountNo ratings yet

- Electronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsDocument9 pagesElectronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsMy AccountNo ratings yet

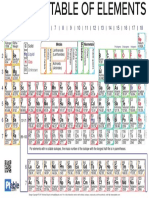

- Periodic Table PDFDocument1 pagePeriodic Table PDFpreetamNo ratings yet

- Electronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsDocument9 pagesElectronics Lab #3: Voltage Dividers and More Complicated CircuitsMy AccountNo ratings yet

- Master social skills and etiquette with this presentationDocument16 pagesMaster social skills and etiquette with this presentationAjay MallavarapuNo ratings yet

- Periodic Table PDFDocument1 pagePeriodic Table PDFpreetamNo ratings yet

- Master social skills and etiquette with this presentationDocument16 pagesMaster social skills and etiquette with this presentationAjay MallavarapuNo ratings yet

- Our Vision Is To-1Document119 pagesOur Vision Is To-1Al RafioNo ratings yet

- Reading comprehension and possessive nouns exercise in EnglishDocument11 pagesReading comprehension and possessive nouns exercise in EnglishAngela Patricia RiosNo ratings yet

- MATERI KD 3.1 BAHASA INGGRIS KELAS X SEMESTER GANJIL-ARIF N Bagian 2Document7 pagesMATERI KD 3.1 BAHASA INGGRIS KELAS X SEMESTER GANJIL-ARIF N Bagian 2Arif NurrahmanNo ratings yet

- Definition of The Present Perfect TenseDocument10 pagesDefinition of The Present Perfect Tenseluis manuelNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Words 1Document42 pagesVocabulary Words 1Maitee AgueroNo ratings yet

- Arabic Grammar Par 00 Soci RichDocument364 pagesArabic Grammar Par 00 Soci RichYaksá HiperbólicoNo ratings yet

- Some and Any Explanation PDFDocument2 pagesSome and Any Explanation PDFjanssNo ratings yet

- Vii Cycle English Quiz #02: FULL NAME: - DATE: - / - / - SCOREDocument3 pagesVii Cycle English Quiz #02: FULL NAME: - DATE: - / - / - SCORESalito de Ap100% (1)

- Teaching Grammar in ESL ClassroomsDocument57 pagesTeaching Grammar in ESL ClassroomsHeaven's Angel LaparaNo ratings yet

- Gerun D: Group 8 Level 1ADocument14 pagesGerun D: Group 8 Level 1APark DhitaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Wonder 6 Test Prep SheetDocument2 pagesUnit 1 Wonder 6 Test Prep SheetfrexmaNo ratings yet

- Eim 2 S&s PDFDocument2 pagesEim 2 S&s PDFiraklius0% (1)

- Membaca Dibaca: Di (Is, Am, Are, Wa, Were, Been Oleh By. Langkah-Langkah Dan Rumus Kalimat PassiveDocument2 pagesMembaca Dibaca: Di (Is, Am, Are, Wa, Were, Been Oleh By. Langkah-Langkah Dan Rumus Kalimat Passivenaziroh herliaNo ratings yet

- The Passive Voice Explanation Grammar Drills Grammar Guides - 24303Document9 pagesThe Passive Voice Explanation Grammar Drills Grammar Guides - 24303Ваня НиколоваNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Frequency Use of The Adverbs of Frequency: AlwaysDocument1 pageAdverbs of Frequency Use of The Adverbs of Frequency: AlwaysMaria Camila FOLLECO NINO100% (1)

- Passive VoiceDocument3 pagesPassive VoicePeterNo ratings yet

- MATERIAL GUIA ERT (Links)Document19 pagesMATERIAL GUIA ERT (Links)Alejandra Nayeli Arreola LeosNo ratings yet

- Namma Kalvi 10th English Minimum Study Material Surya Guide 216703Document209 pagesNamma Kalvi 10th English Minimum Study Material Surya Guide 216703Sakthi SakthiNo ratings yet

- Helping Verb6Document5 pagesHelping Verb6samreeniqbalNo ratings yet

- Order of AdjectivesDocument2 pagesOrder of AdjectivesYajaira Navarro100% (1)

- Compound Words WorksheetDocument2 pagesCompound Words WorksheetRicky YoungNo ratings yet

- Presentasi Bahasa Inggris Recount TextDocument21 pagesPresentasi Bahasa Inggris Recount TextAcha100% (1)