Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Measuring Adolescent Attitudes Toward Classroom Incivility: Exploring Differences Between Intentional and Unintentional Incivility

Uploaded by

Leandro CardosoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring Adolescent Attitudes Toward Classroom Incivility: Exploring Differences Between Intentional and Unintentional Incivility

Uploaded by

Leandro CardosoCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/288888209

Measuring Adolescent Attitudes Toward Classroom Incivility:

Exploring Differences Between Intentional and Unintentional

Incivility

Article in Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment · December 2015

DOI: 10.1177/0734282915623446

CITATIONS READS

18 1,031

5 authors, including:

Ann H. Farrell Natalie Spadafora

Brock University McMaster University

40 PUBLICATIONS 364 CITATIONS 34 PUBLICATIONS 115 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Zopito Marini Anthony A. Volk

Brock University Brock University

48 PUBLICATIONS 2,092 CITATIONS 108 PUBLICATIONS 3,656 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

"Transdisciplinarity and Child and Youth Studies: what are the links?" View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Anthony A. Volk on 15 August 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

623446

research-article2015

JPAXXX10.1177/0734282915623446Journal of Psychoeducational AssessmentFarrell et al.

Article

Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment

2016, Vol. 34(6) 577–588

Measuring Adolescent Attitudes © The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

Toward Classroom Incivility: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0734282915623446

Exploring Differences Between jpa.sagepub.com

Intentional and Unintentional

Incivility

Ann H. Farrell1, Daniel A. Provenzano1, Natalie Spadafora1,

Zopito A. Marini1, and Anthony A. Volk1

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop a scale that measures adolescents’ attitudes toward

classroom incivility and determine whether items would reveal subscales. A sample of 549

adolescents between ages 11 and 18 (53.1% boys; Mage = 13.90, SD = 1.41) completed items

written to measure attitudes toward classroom incivility. An exploratory factor analysis

(EFA) was used on one half of the randomly split sample and a confirmatory factor analysis

(CFA) on the remainder. Results from both analyses suggested that two factors representing

unintentional and intentional incivility might be the best factor solution. In addition, evidence

for concurrent validity was found in correlations with four additional scales. Results suggest

that attitudes toward classroom incivility are heterogeneous and that adolescence may be an

important developmental period to address this construct. Future studies should continue

psychometrically developing this scale and exploring this measure with additional antisocial

beliefs and behaviors.

Keywords

classroom incivility, intentional, unintentional, adolescence, scale development

Introduction

The decline of civility in the classroom has recently been a concern in education (Bjorklund &

Rehling, 2009). Civility is defined as “polite behaviours that maintain social harmony, or demon-

strate respect for the humanity of an individual, important in maintaining a society” (Wilkins,

Caldarella, Crook-Lyon, & Young, 2010, p. 37). To conceptualize civility, two aspects must be

examined. The “civic” aspect focuses on citizenship (i.e., being aware of the others’ well-being)

and the “civil” aspect focuses on creating “learning relationships” to ensure others’ well-being

(Marini, Polihronis, & Blackwell, 2010). The opposite of civility, however, is incivility, which is

1Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Ann H. Farrell, Department of Psychology, Brock University, 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, Ontario,

Canada L2A3A1.

Email: af08tl@brocku.ca

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

578 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

the focus of this article. Andersson and Pearson (1999) defined incivility as “low intensity, devi-

ant behavior with ambiguous intent to cause harm” (p. 457). These uncivil attitudes and actions

include a general disregard for others (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Furthermore, what differen-

tiates incivility from other antisocial behaviors such as aggression and bullying are the aspects of

low intensity and ambiguous intent.

Multidimensional Model of Incivility

To better understand the concept of incivility, a clearer distinction should be made between acts

and methods of incivility. Marini (2009) described the major continuums of incivility: the form

(ranging from indirect to direct) and function (ranging from reactive to proactive). Indirect inci-

vility would be negative actions carried out covertly, whereas direct incivility would be imple-

mented overtly (Marini, 2009). On the opposing continuum, proactive incivility includes uncivil

actions used to attain a resource (i.e., stealing notes), whereas reactive incivility includes uncivil

actions used as retaliation (Marini, 2009). Thus, incivility encompasses both attitudinal and

behavioral aspects.

Along with these distinctions, incivility can also be conceptualized as being intentional or

unintentional. Intentionally uncivil actions are planned with a clear intent to harm, similar to

proactive incivility (Marini et al., 2010). An example includes spreading rumors about a class-

mate (Marini, 2009), as this action is done with intent to hurt that individual. Unintentional inci-

vility is done through inattention or thoughtlessness, rather than with intent to harm (Marini

et al., 2010). An example includes checking your email during class, as this is done without

intentions to harm but could be perceived as disrespectful.

Research has generally focused on higher intensity antisocial behaviors such as aggression

instead of lower intensity behaviors such as incivility (Eggertson, 2011; Lim, Cortina, & Magley,

2008). However, antisocial attitudes and forms of aggression should be examined to see if they

have similar origins (Marini, 2007). In addition, research on incivility primarily focuses on adult

workplace incivility or college classroom incivility. Within the workplace, incivility can affect

the attitudes and behaviors of employees (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Pearson & Porath, 2005).

Considering the negative outcomes associated with workplace incivility and the lack of research

on incivility among younger samples, the present study will focus on adolescent classroom

incivility.

Classroom In/Civility

Adolescence may be a crucial time to address incivility before behaviors become more serious.

Thus, it is increasingly important to focus on classroom incivility as it may affect both academic

and personal development (Marini, 2009). Feldmann (2001) defined classroom incivility as “any

action that interferes with a harmonious and cooperative learning atmosphere” (p. 137).

Classroom incivility has the potential to disrupt the learning environment and teaching capabili-

ties of the institution (Feldmann, 2001). Educators may often ignore uncivil behaviors to have

more instructional time and may believe these behaviors may disappear on their own. However,

not addressing uncivil behaviors may signal to students that these behaviors are acceptable,

which may encourage repetition (Feldmann, 2001). Therefore, it is important to understand ado-

lescent attitudes about uncivil behaviors to understand the origins.

Boice (1996) found classroom incivility was common, where two thirds of classes showed

such behaviors. Thus, it is important to address classroom incivility as there are many asso-

ciated negative outcomes. For instance, a short-term consequence includes limited class

engagement, whereas a long-term outcome includes not reaching educational goals (Hirschy

& Braxton, 2004). Moreover, incivility may reduce student commitment to current and

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

Farrell et al. 579

post-secondary education (Hirschy & Braxton, 2004). Therefore, it is important to address

this phenomenon during adolescence, a period when social ties are forming and community

building is fundamental (Schaefer, 1995). Furthermore, addressing these behaviors early

may prevent development of more serious antisociality in post-secondary institutions or in

the workplace (Boice, 1996).

Previous Measures of Classroom Incivility

To explore incivility, a valid and reliable measure relevant for adolescents is needed. Although

research suggests classroom incivility has increased, there are limited measures that exist to

examine adolescent thoughts on incivility (Wilkins et al., 2010). One known measure created by

Indiana University (Royce, 2000) assesses faculty perceptions of classroom incivility. In this

measure, faculty members are asked what behaviors they consider to be uncivil, the frequency,

and associated demographics (Royce, 2000). Thus, this measure does not assess students’ percep-

tions of incivility and targets older university students. However, several researchers have

adapted this scale to assess university students’ perceptions.

For example, a study by Nordstrom, Bartels, and Bucy (2009) adapted the Indiana University

(Royce, 2000) survey to assess college students’ perceptions of incivility. This scale included

items about negative (i.e., using cell phones in class) and positive or neutral (i.e., raising hands

in class) classroom behaviors. Students were asked the appropriateness and frequency in

engagement of each behavior. Similarly, researchers have developed scales on student percep-

tions of classroom incivility by creating 10 (Boice, 1996) to more than 20 (Al Kandari, 2011;

Bjorklund & Rehling, 2009) items compiled from existing research (e.g., Caboni, Hirschy, &

Best, 2004). All studies asked students to rate how uncivil they thought each item was. According

to Boice (1996), the most commonly reported uncivil behaviors by students included starting

class early, stopping class late, and disruptive students. Furthermore, the study found that as

classroom incivility increased, students were more likely to engage in additional disruptive

behaviors and were less involved in learning. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that

although a few measures of classroom incivility exist, they measure the attitudes of students in

college and university instead of middle and high school. These young adults are developmen-

tally different from adolescents. Furthermore, the structure of classrooms and lessons are differ-

ent for colleges and universities, in comparison with middle and high schools. Therefore, it is

evident that a scale is needed to measure similar uncivil attitudes with items that are relevant

specifically for adolescents.

Current Study

Most research on attitudes on incivility has been conducted on young adults in post-secondary

institutions or adults in the workplace. Although these scales may be valid and reliable for their

target sample, the items may not be developmentally relevant to incivility specifically for adoles-

cents in a secondary school classroom. To our knowledge, there are no scales that measure ado-

lescents’ attitudes toward classroom incivility. As a result, there were two main goals of the

present study: (a) develop a Classroom Incivility scale with items that are relevant to adolescents’

attitudes and (b) determine whether subscales of incivility would emerge in this scale. We hypoth-

esized that subscales would emerge based on behavior intentionality (i.e., intentional or uninten-

tional). Finally, to provide evidence for concurrent validity, we correlated emerging subscales of

incivility with three measures of antisociality (antisocial beliefs, friend antisociality, and conduct

problems) and a measure of prosocial behavior. We predicted significant positive correlations

between all types of incivility and measures of antisociality and a significant negative correlation

between incivility and prosocial behavior.

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

580 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

Method

Participants

Adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 (N = 549, 53.1% boys; Mage = 13.90, SD = 1.41) were

recruited from extracurricular activities in Southern Ontario, including sports teams and youth

groups. Participants were recruited for a larger study on adolescent relationships. Self-reported

ethnicities included Caucasian (70.9%), Asian (2.9%), Hispanic (1.8%), African-Canadian

(1.8%), Mixed (1.8%), Indigenous peoples (1.1%), and Other (9.0%). The remainder did not

report ethnicity (10.7%). For self-reported perceptions of socioeconomic status (SES), the major-

ity of adolescents reported his or her family to be “about the same” (66.4%) in wealth as the

average Canadian, whereas fewer reported “more rich” (21.4%) and “less rich” (10.9%). The

remainder (1.3%) did not report SES.

A subsample of participants completed measures for scales added during a later phase of data

collection, which were used to assess concurrent validity. These subsamples include antisocial

beliefs (n = 278, 51.1% girls; Mage = 13.79, SD = 1.34), friend antisociality (n = 191, 51.8% boys;

Mage = 13.92, SD = 1.49), conduct problems (n = 313, 53.4% boys; Mage = 13.87, SD = 1.34), and

prosocial behavior (n = 319, 52.0% boys; Mage = 13.79, SD = 1.32).

Measures

Incivility. Questionnaires were presented in random order. Participants completed 11 items written

to measure a variety of attitudes toward incivility relevant to adolescents. Items were selected from

a pool of 20 items written for previous work on developing an Adolescent Classroom Incivility

scale (Marini, 2007). Although this study was unpublished, we narrowed down the number of items

we thought were most relevant to reduce the length of the scale. The questionnaire asked, “Please

circle the answer that best describes your belief about each of the following situations.” A sample

item for unintentional incivility is “Packing up books before a lesson is over.” A sample item for

intentional incivility is “Calling a classmate names because they did not agree with your opinion.”

Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = definitely wrong to 5 = definitely okay).

Antisocial beliefs. Participants completed a modified 11-item version of the Attitudinal Intolerance of

Deviance Scale (α = .86; Jessor, Van Den Bos, Vanderryn, Costa, & Turbin, 1995). The questionnaire

asked to check the box that best fit how wrong they thought it was to behave in the way described in

each item. A sample item includes, “To take little things that don’t belong to you.” Items were rated

on a 5-point scale (1 = very wrong to 5 = not at all wrong). An average score was computed.

Friend antisociality. Participants completed a modified seven-item version of the Delinquent Peer

Exposure Scale (α = .82; Mazerolle & Maahs, 2000). Participants were asked how many of their

friends have engaged in delinquent activities. A sample item includes, “Skipped school without

an excuse?” Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = none of them to 5 = all of them). An average

score was computed.

Conduct problems. Participants completed a five-item version of the Conduct Problems subscale

of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (α = .40; Goodman, Meltzer, & Bailey, 1998),

which asked to check the box that best described their opinion for each statement. A sample item

includes, “I get very angry and often lose my temper.” Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0 =

not true to 2 = certainly true). An average score was computed.

Prosocial behavior. Participants completed a five-item version of the Prosocial Behavior subscale

of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (α = .60; Goodman et al., 1998), which asked to

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

Farrell et al. 581

check the box that best described their opinion for each statement. A sample item includes, “I try

to be nice to people and care about their feelings.” Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not

true to 2 = certainly true). An average score was computed.

Procedure

After university ethics approval, extracurricular activity leaders were contacted for consent to

approach adolescents. Once consent was obtained, the researchers went to the activities and

invited adolescents to participate in a study on adolescent relationships. Interested participants

were given two envelopes: one with a parental consent form and the second with an assent form

and questionnaires. Participants were informed that both forms needed signatures for question-

naires to be used and to complete the questionnaires in private. Approximately 1 week later,

researchers returned, collected completed packages, and debriefed participants. Participants were

given C$15 in compensation.

Data Analysis

After missing data and plausible values were assessed, the sample was randomly split in half. For

the first half, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with promax

rotation (Costello & Osborne, 2005; Norris & Lecavalier, 2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013) was

conducted with the 11 items using SPSS 22 software. We decided to conduct an EFA first because

our study was exploratory in nature, and to our knowledge, no studies exist on developing ado-

lescents’ attitudes toward incivility. Therefore, we did not specify the number of factors in our

model. We used a promax rotation as we expected subscales would be oblique. We used multiple

oblique rotations and found that all yielded similar factor solutions and loadings. Item loadings

were assessed to determine which factor each item should be assigned to, and items with poor

loadings were excluded. EFA was then rerun with remaining items to determine whether the

number of factors and loadings changed as a result of the exclusion.

Following the EFA, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 22 soft-

ware on the second half of the randomly split sample. The CFA was conducted to determine

whether our hypothesis that subscales based on intentionality would be supported and to see

whether results similar to the EFA would be found. Therefore, we assigned the items to two fac-

tors based on the item loadings from the EFA. Finally, to assess concurrent validity, composite

scores of the two subscales were created and correlated with antisocial beliefs, friend antisocial-

ity, conduct problems, and prosocial behavior for a subsample of participants who had completed

these four scales.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Assessment of missing data revealed that three items had one missing case, two items had two

missing cases, four items had three missing cases, and two items had 100 missing cases.

Expectation–Maximization (EM) Estimated Statistics with a criterion of p < .05 revealed that the

data may not be missing completely at random, χ2(127) = 174.10, p = .004, although there were

no age and sex differences. Missing data were likely due to the fact that the two items with the

most number of missing cases were added to the questionnaires at a later point in the data collec-

tion. Missing cases were not replaced to prevent any biases. Pairwise deletions were used for

subsequent analyses, reducing the sample size to 247 for the EFA and 246 for the CFA. All

descriptive values were plausible (see Tables 1 and 2). Six items had univariate outliers outside

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

582 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

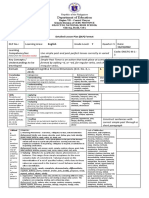

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics, Factor Loadings, Communalities (h2), and Percentage of Variance for

EFA With Promax Rotation on Final Incivility Items.

Item Factor 1 Factor 2 H2 n M (SD)

Posting nasty notes 0.86 –0.21 0.74 247 1.27 (0.75)

Calling classmate names 0.78 0.04 0.60 247 1.28 (0.68)

Fighting with student 0.77 0.02 0.59 247 1.41 (0.84)

Spreading rumors 0.69 –0.02 0.48 199 1.47 (0.86)

Making fun of classmate 0.57 0.22 0.32 247 1.59 (0.87)

Eating during class –0.04 0.77 0.59 247 3.06 (1.17)

Packing up books –0.31 0.72 0.52 247 2.55 (1.28)

Online during a lesson 0.08 0.69 0.48 247 2.38 (1.31)

Sending a text in class 0.04 0.66 0.43 247 1.98 (1.14)

Sleeping in class 0.26 0.56 0.31 246 1.80 (1.04)

Percentage of variance 42.03 11.41

Note. Loadings more than 0.45 (20% variance) are bolded to facilitate interpretation. EFA = exploratory factor

analysis; Factor 1 = intentional incivility; Factor 2 = unintentional incivility.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Standardized Factor Loadings for CFA on Final Incivility Items (N = 246).

Item Factor 1 Factor 2 M (SD)

Posting nasty notes 0.77 1.22 (0.63)

Spreading rumors 0.88 1.30 (0.64)

Calling classmate names 0.75 1.39 (0.74)

Fighting with student 0.80 1.39 (0.83)

Making fun of classmate 0.68 1.60 (0.94)

Packing up books 0.53 3.04 (1.26)

Eating during class 0.70 2.36 (1.22)

Sending a text in class 0.74 2.34 (1.32)

Online during a lesson 0.80 1.89 (1.10)

Sleeping in class 0.76 1.76 (1.08)

Note. CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; Factor 1 = intentional incivility; Factor 2 = unintentional incivility.

of the |3.29| cutoff for standardized scores (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), and there were three

multivariate outliers outside the χ2(10) = 29.59 cutoff. However, outliers were expected as some

items measuring incivility are often considered more antisocial than other items. Therefore, all

outliers were kept in subsequent analyses. Interitem correlations ranged from small to moderate

(.16-.65), reflecting no issues with multicollinearity. All items met the assumptions of multivari-

ate normality and linearity.

EFA

After conducting an EFA with promax rotation on the 11 items, we decided on a two-factor solu-

tion, which accounted for 52.72% of the variance in incivility. We decided on this solution

because two factors had eigenvalues that were greater than 1, and the greatest jump in eigenval-

ues occurred after Factors 2 and 3. After exploring the items and loadings on the pattern matrix

and using a cutoff value of 0.45 (20% variance; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), the first factor

reflected intentional incivility and consisted of five items. The second factor reflected uninten-

tional incivility and consisted of six items. Both factors had good internal-consistency

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

Farrell et al. 583

reliabilities (intentional: α = .86, unintentional: α = .84) and a large correlation between the two

factors (r = .59). After exploring the structure matrix, one item representing unintentional incivil-

ity had relatively equal correlations to both factors, despite a higher loading on unintentional. To

maximize the differences of the two factors and maintain consistency in the number of items for

each factor, a second EFA was conducted after removing this item.

The second EFA with 10 items demonstrated a similar factor solution with the greatest jump in

eigenvalue after Factor 2, and therefore, we retained two factors accounting for 53.44% of vari-

ance. After exploring the items and loadings on the pattern matrix, the first factor reflected unin-

tentional incivility, whereas the second factor reflected intentional incivility. Both factors consisted

of the same items as in the first EFA. After removing the one item, the internal-consistency reli-

ability for unintentional incivility was still good (α = .82). There was also still a large correlation

between the two factors (r = .56). See Table 1 for rotated loadings on factors, communalities, and

percentage of variance. Average scores for each factor revealed plausible means and standard

deviations (intentional: M = 1.43, SD = 0.67; unintentional: M = 2.35, SD = 0.91).

CFA

Based on the results of the EFA, we tested how well the items loaded onto a two-factor solution,

where five items loaded on each factor and the two factors were allowed to correlate. The results

indicated a poor model fit when assessing model chi-square, χ2(34) = 64.274, p = .001. However,

a significant model chi-square is often found in larger sample sizes, and therefore, other fit indi-

ces should be explored to determine model fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Examining these

additional fit indices using Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2013) criteria indicated good model fit. The

relative chi-square using a cutoff of <0.20 indicated good model fit (χ2/df = 1.890). Using a cutoff

of >0.95, both the goodness of fit index (GFI = 0.952) and the comparative fit index (CFI =

0.975), demonstrated good model fits. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation

(RMSEA) using a cutoff of ≤0.60 indicated good model fit (RMSEA = .06, 90% CI = [0.41,

0.81]). Therefore, our hypothesized two-factor model was supported by our observed data. Both

factors had good internal-consistency reliabilities (intentional: α = .87, unintentional: α = .83),

and there was a high correlation between the two factors (r = .69). All standardized factor load-

ings were larger than 0.53, indicating large loadings (see Table 2). Average scores for each factor

revealed plausible means and standard deviations (intentional: M = 1.40, SD = 0.64; uninten-

tional: M = 2.28, SD = 0.93).

See the appendix for a list of the final items for each subscale. In summary, two factors repre-

senting intentional and unintentional incivility, with five items each, may be the best solution.

Concurrent Validity

Subscales of incivility revealed moderate correlations with measures of antisociality and small cor-

relations with prosocial behavior. For antisocial beliefs, the correlations with unintentional and inten-

tional incivility were .57 and .43 (ps < .001, n = 278), respectively. For friend antisociality, the

correlations with unintentional and intentional incivility were .50 and .49 (ps < .001, n = 191), respec-

tively. For conduct problems, the correlations with unintentional and intentional incivility were .35

and .29 (ps < .001, n = 313), respectively. For prosocial behavior, the correlations with unintentional

and intentional incivility were −.19 (p = .001) and −.22 (p < .001, n = 319), respectively.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a scale to measure adolescents’ attitudes on different

types of classroom incivility. As hypothesized, the EFA and CFA indicated subscales of incivility

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

584 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

based on the function of the behavior (i.e., intentional and unintentional) with similar sizes of

item loadings, means, standard deviations, and correlations between the two subscales. These

results support previous studies that suggested incivility can be conceptualized along a contin-

uum of intentionality (e.g., Hunt & Marini, 2012). Previous research on incivility has conceptual-

ized the behavior in a number of different ways. However, we believe that the intentional facet of

incivility from our scale overlaps with Hunt and Marini’s (2012) proactive facet of their

Multidimensional Model, given that both intentional and proactive behaviors are deliberately

meant to harm others (i.e., spreading rumors about a classmate you dislike). By demonstrating

that our scale measures attitudes on different subtypes of classroom incivility, it may help pro-

vide a better understanding of how this construct can be conceptualized.

Factors did not emerge based on the form of the behavior, suggesting that the items had more

commonalities based on attitudes of intentionality. Perhaps both intentional and unintentional

incivilities may share multiple forms of behavior with the same function (Marini, 2009). For

example, intentional incivility can be both direct (i.e., fighting with a student) and indirect (i.e.,

spreading rumors). In addition, the correlation between the two subtypes was moderate in size,

suggesting that although attitudes on intentional and unintentional subtypes may share an overlap

in incivility, they may still have independent factors, reflecting differences in function of the

behaviors.

Furthermore, based on the item mean ratings for both the EFA and CFA, intentional incivility

was more positively skewed. In other words, adolescents rated the intentional items to be more

uncivil than the unintentional items. This further reflects previous research suggesting that incivil-

ity should be thought of as a continuum ranging from low (i.e., cell phone ringing or packing up

books before class is over) to high intensity (i.e., insults or threats made toward other students;

Marini et al., 2010). Specifically, low intensity uncivil behaviors are considered minor occur-

rences, whereas high intensity behaviors are considered more serious, especially if safety becomes

an issue (Marini, 2009). Although we did not measure frequency, perhaps the acceptability of

minor occurrences may reflect the high frequency of these behaviors found in previous studies

(e.g., Boice, 1996) in comparison with more serious behaviors that may occur less frequently.

Finally, the significant correlations between both subtypes of incivility with antisocial beliefs,

friend antisociality, conduct problems, and prosocial behavior provide evidence for concurrent

validity. As expected, both types of incivility revealed positive moderate correlations with other

antisocial variables and negative small correlations with prosocial behavior. However, it is

important to note that the Cronbach’s alphas for conduct problems and prosocial behavior were

unusually low for the well-established Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, and therefore,

the results should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, these correlations provided evidence

for concurrent validity.

Implications

Theory. The findings have implications for the conceptualization of incivility. Developing a

Classroom Incivility scale to measure the attitudes toward different subtypes of incivility demon-

strates adolescents can think of an uncivil behavior as being both intentional and unintentional.

Previous research has suggested the heterogeneity of uncivil behaviors, ranging from low to high

intensity, active to passive, and part of a Multidimensional In/Civility Identification Model (Hunt

& Marini, 2012). In addition to these dimensions, our scale provides support for a continuum

ranging from unintentional to intentional.

Furthermore, Marini (2007) has suggested a conceptual link between incivility and other anti-

social behaviors. Behaviors exhibited in both classroom incivility and bullying may originate

from similar cognitive and emotional structures including problems forming healthy relation-

ships (Marini, Dane, & Kennedy, 2010; Marini, Polihronis, Dane, & Volk, 2010). This suggests

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

Farrell et al. 585

attitudes on classroom incivility may be a potential precursor to more serious antisocial behav-

iors, such as bullying, harassment, or aggression (Eggertson, 2011; Lim et al., 2008; Marini,

2007). Therefore, future studies looking at the link between incivility and antisocial behaviors

may want to make distinctions based on intentionality.

Practice. The findings also have implications for interventions. General interventions may want

to focus on reducing less severe uncivil behaviors earlier in adolescence to prevent more severe

antisocial behaviors later in development (Wilkins et al., 2010). One of the most effective meth-

ods previously found may be fostering a classroom environment that promotes civility (Wilkins

et al., 2010). However, general interventions may treat incivility as a homogeneous behavior.

Considering our results on the subtypes, a general intervention may not be the most effective

method for adolescents. In fact, previous research has found antibullying interventions to be

largely ineffective (e.g., Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), which may in part be due to treating bullying

as a homogeneous behavior (Volk, Camilleri, Dane, & Marini, 2012). If incivility and bullying

are conceptually linked, then interventions may also want to treat incivility as a heterogeneous

behavior.

For more specific strategies, Marini (2009) suggested that types of uncivil classroom behav-

iors may first need to be distinguished. Disruptive behaviors can arise from students who are

unaware of the rules and expected classroom norms (i.e., unintentional incivility) or can arise

from students trying to harm others (i.e., intentional incivility). Because there is a distinction

between the different types of disruptive behavior, interventions can be tailored specifically to

the needs of those students who fall into one of those subtypes.

According to Feldmann (2001), for students who lack the knowledge of appropriate classroom

behavior, teachers can take a proactive approach. For example, at the beginning of a school year,

teachers can outline the expectations with a syllabus that includes course instructions and objec-

tives. Feldmann also suggests that throughout the school year, teachers can foster classroom

civility by maintaining an open dialogue with students. Meanwhile, for students who participate

in uncivil behaviors to harm others, Feldmann suggests that teachers can take an educative

approach. For example, Marini (2009) suggested that after a transgression, teachers could calmly

discuss civility individually with that student and also remind the class about the importance of

harmonious relationships. In addition, teachers can get support from other faculty at the school

in promoting civility. For example, Feldmann suggests if a teacher is having difficulty addressing

a student, they may ask another faculty member for assistance. Thus, all faculty members may

help encourage a positive school climate.

Although school faculty plays an important role in establishing classroom civility, students

may also contribute. Uncivil attitudes and actions can disrupt students’ concentration on school-

work (Hirschy & Braxton, 2004). By encouraging students to take responsibility for their own

learning, they may be more focused on their schoolwork, which could reduce their inclination to

engage in uncivil behaviors (Lewis, 2001). These strategies demonstrate how students and fac-

ulty can work together to maintain classroom civility.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

There were a few limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, self-report mea-

sures were used to obtain intentional and unintentional incivility, and thus, results are limited to

adolescent perceptions of classroom incivility. However, this is a first step at developing an

Adolescent Classroom Incivility scale. Future studies may want to adapt such items to measure

the observations of peers or teachers as have been done with college students (Royce, 2000).

Items may also be adapted to measure incivility in younger samples in elementary school to

investigate their attitudes on incivility, which may allow for earlier interventions.

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

586 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

A second limitation was that we assessed beliefs on incivility as opposed to the frequency of

uncivil behaviors. Thus, we were not able to determine the prevalence of classroom incivility. It

is possible that the factor structure of incivility may be different for behaviors in comparison with

attitudes. However, exploring perceptions of what is considered an uncivil behavior is the first

step in addressing them (Peter, 2011). Future studies may want to incorporate frequency with this

scale to compare factor structures.

A third limitation was that we know the subtypes of incivility, but are not yet sure what they

are related to. Future studies should explore this measure in the context of additional individual

differences and antisocial behaviors. This may help reveal which factors contribute to incivility

or how it may be linked to more serious antisocial behavior. For example, as has already been

done with other antisocial behaviors such as bullying (e.g., Book, Volk, & Hosker, 2012), future

studies may investigate personality traits that may be related to uncivil behaviors.

Seeing as this is the first study on the “Attitude Toward Classroom In/Civility Scale,” there are

several future directions for psychometric evaluation and development. First, several studies can

examine validity. Considering that we found evidence for concurrent validity, future studies may

want to explore predictive validity with other scales of classroom incivility, or additional scales

of antisociality, such as aggression or bullying. In addition, researchers may look at convergent

and discriminant validity by developing observer reports, such as peer or teacher reports. Second,

researchers may want to look at the reliability in other adolescent samples. For instance, research-

ers may want to replicate our exploratory study with the other samples to determine whether

subscales based on intentionality emerge.

In summary, in this study, we developed a Classroom Incivility scale for adolescents and

revealed two subscales: Intentional and Unintentional. This suggests that adolescent incivil-

ity is heterogeneous, and future studies should explore how these subtypes differentially

associate with both individual- and social-level factors, as well as other types of antisocial

behaviors.

Appendix

Attitudes Toward Classroom In/Civility Questionnaire

Final list of items for Incivility scale broken down by unintentional and intentional incivility:

Unintentional incivility

1. Packing books up before a lesson is over

2. Sending text messaging or notes during class

3. Reading, going online, or playing a game during a lesson

4. Eating lunch during class

5. Sleeping in class

Intentional incivility

1. Making fun of a classmate who answered a question wrong

2. Posting nasty notes on bulletin boards about a classmate

3. Calling a classmate names because they did not agree with your opinion

4. Spreading rumors about or try to exclude a classmate you dislike

5. Fighting with another student in class (physical or verbal)

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or

publication of this article.

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

Farrell et al. 587

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Al Kandari, N. (2011). The level of student incivility: The need of a policy to regulate college student inci-

vility. College Student Journal, 45, 257-268.

Andersson, L., & Pearson, C. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiralling effect of incivility in the workplace.

Academy of Management Review, 24, 452-471.

Bjorklund, W., & Rehling, D. L. (2009). Student perceptions of classroom incivility. College Teaching,

58, 15-18.

Boice, R. (1996). Classroom incivilities. Research in Higher Education, 37, 453-485.

Book, A., Volk, A. A., & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: An adaptive approach.

Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 218-223.

Caboni, T. C., Hirschy, A. S., & Best, J. R. (2004). Student norms of classroom decorum. New Directions

for Teaching and Learning, 99, 59-66.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommenda-

tions for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(7).

Retrieved from http://pareonline.net/pdf/v10n7.pdf

Eggertson, L. (2011). Targeted: The impact of bullying and what needs to be done to eliminate it. Canadian

Nurse, 107, 16-20.

Feldmann, L. J. (2001). Classroom civility is another of our instructor responsibilities. College Teaching,

49, 137-140.

Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., & Bailey, V. (1998). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A pilot study

on the validity of the self-report version. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 7, 125-130.

Hirschy, A. S., & Braxton, J. M. (2004). Effects of student classroom incivilities on students. New Directions

for Teaching & Learning, 99, 67-76.

Hunt, C., & Marini, Z. A. (2012). Incivility in the practice environment: A practice from clinical nursing

teachers. Nurse Education in Practice, 12, 366-370.

Jessor, R., Van Den Bos, J., Vanderryn, J., Costa, F. M., & Turbin, M. S. (1995). Protective factors in adolescent

problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology, 31, 923-933.

Lewis, R. (2001). Classroom discipline and student responsibility: The students’ view. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 17, 307-319.

Lim, S., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and

health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 95-107.

Marini, Z. A. (2007). The Academic In/Civility Questionnaire (AI/CQ-V.1): Assessing intentional and

unintentional in/civility (Unpublished manuscript). Department of Child and Youth Studies, Brock

University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada.

Marini, Z. A. (2009). The thin line between civility and incivility: Fostering reflection and self-awareness to

create a civil learning community. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 2, 61-67.

Marini, Z. A., Dane, A., & Kennedy, R. (2010). Multiple pathways to bullying: Tailoring educational

practices to variations in students’ temperament and brain function. In M. Ferrari & L. Vuletic (Eds.),

Developmental interplay of mind, brain, and education: Essays in honour of Robbie Case (pp. 257-291).

New York, NY: Springer.

Marini, Z. A., Polihronis, C., & Blackwell, W. (2010). Academic in/civility: Co-constructing the foundation

for a civil learning community. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 3, 89-93.

Marini, Z. A., Polihronis, C., Dane, A., & Volk, A. (2010, June). Towards the development of a civil

learning community: Differentiating between intentional and unintentional in/civility. Poster ses-

sion presented at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (STLHE) 30th Annual

Conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Mazerolle, P., & Maahs, J. (2000). General strain and delinquency: An alternative examination of condi-

tioning influences. Justice Quarterly, 17, 753-778.

Nordstrom, C. R., Bartels, L. K., & Bucy, J. (2009). Predicting and curbing classroom incivility in higher

education. College Student Journal, 43, 74-85.

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

588 Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 34(6)

Norris, M., & Lecavalier, L. (2010). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in developmental

disability psychological research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 8-20.

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility:

No time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 7-18.

Peter, E. (2011). Fostering social justice: The possibilities of a socially connected model of moral agency.

Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 43, 11-17.

Royce, A. P. (2000). A survey on academic incivility at Indiana University: Preliminary report. Bloomington:

Center for Survey Research, Indiana University.

Schaefer, L. (1995). Reinventing civility. NAMTA Journal, 20, 138-147.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A

systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 27-56.

Volk, A. A., Camilleri, J. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2012). Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary

adaptation? Aggressive Behavior, 38, 222-238.

Wilkins, K., Caldarella, P., Crook-Lyon, R., & Young, K. R. (2010). Implications of civility for children

and adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues in Religion and Psychotherapy, 33, 37-45.

Downloaded from jpa.sagepub.com at BROCK UNIV on August 15, 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Manual-Coach-yourself EMDR 6-StepsDocument94 pagesManual-Coach-yourself EMDR 6-StepsRosalía Pérez RuizNo ratings yet

- Magic of FaithDocument0 pagesMagic of Faithqford.global5298100% (6)

- Conversational Dashboard: DistrustDocument1 pageConversational Dashboard: DistrusttigerloveNo ratings yet

- MisbeliefDocument23 pagesMisbeliefnyq2qkbpvz100% (1)

- FrameworksDocument54 pagesFrameworksKaren RoseNo ratings yet

- A Systems View of Mother-Infant Face-to-Face Communication: Developmental Psychology February 2016Document17 pagesA Systems View of Mother-Infant Face-to-Face Communication: Developmental Psychology February 2016inesbominoNo ratings yet

- Evidence of Moderation PracticeDocument4 pagesEvidence of Moderation Practiceapi-350555574No ratings yet

- Ling-6 Sound Test - How ToDocument7 pagesLing-6 Sound Test - How ToJohnson JayarajNo ratings yet

- Parents' Self-Reported AttachmentDocument33 pagesParents' Self-Reported AttachmentAnca GurzaNo ratings yet

- Perfectionism in Gifted Adolescents: A Replication and ExtensionDocument20 pagesPerfectionism in Gifted Adolescents: A Replication and ExtensionStefan HlNo ratings yet

- Tongwei Tak DonDocument14 pagesTongwei Tak DonNguyễn Việt TùngNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Automatic ProcessingDocument8 pagesJurnal Automatic ProcessingDesi Laila AmriNo ratings yet

- Running Head: ARTICLE CRITIQUEDocument19 pagesRunning Head: ARTICLE CRITIQUEpatrick wafulaNo ratings yet

- Fletcheretal 2015PPSPairBondingLoveandEvolutionDocument18 pagesFletcheretal 2015PPSPairBondingLoveandEvolutionCristina TudoranNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders Risk FactorsDocument25 pagesEating Disorders Risk FactorsBhumika BhallaNo ratings yet

- Pi Wi Scale Development P MM 2018Document18 pagesPi Wi Scale Development P MM 2018andinurzamzamNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Research: Intimate Adult Relationships Introduction: Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory Studies ofDocument9 pagesCross-Cultural Research: Intimate Adult Relationships Introduction: Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory Studies ofwqewqewrewNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Research: Intimate Adult Relationships Introduction: Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory Studies ofDocument9 pagesCross-Cultural Research: Intimate Adult Relationships Introduction: Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory Studies ofwqewqewrewNo ratings yet

- Self-Compassion From Adolescent PerspectiveDocument24 pagesSelf-Compassion From Adolescent PerspectiveArzaci ArzaciNo ratings yet

- Psaltis Zapiti 2016 Published PDFDocument8 pagesPsaltis Zapiti 2016 Published PDFLucienne IrianaNo ratings yet

- Screening Bully and Victim - Farmani2021Document24 pagesScreening Bully and Victim - Farmani2021Raluca GeorgescuNo ratings yet

- Brown Stanton Watson JOBA2020Document18 pagesBrown Stanton Watson JOBA2020royNo ratings yet

- Oracle Summer 2015Document89 pagesOracle Summer 2015Asad khanNo ratings yet

- 2001 - JAP - Misunderstanding Analysis of CovarianceDocument9 pages2001 - JAP - Misunderstanding Analysis of CovarianceBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- SeneseEtAl2016 MI PARQDocument39 pagesSeneseEtAl2016 MI PARQdevyani tapariaNo ratings yet

- Interactive and Mediational Etiologic Models of Eating Disorder Onset: Evidence From Prospective StudiesDocument25 pagesInteractive and Mediational Etiologic Models of Eating Disorder Onset: Evidence From Prospective StudiesZaiaNo ratings yet

- Lilienfeld Et Al. (2014) - Why Ineffective Psychotherapies Appear To WorkDocument35 pagesLilienfeld Et Al. (2014) - Why Ineffective Psychotherapies Appear To WorkNathalia RochaNo ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Study On The Influences of Gender Based Friendships Among Regional Science High School For Region VI StudentsDocument104 pagesA Phenomenological Study On The Influences of Gender Based Friendships Among Regional Science High School For Region VI StudentsShane UretaNo ratings yet

- 2002TCPLiving Up ToParentalExpectationInventoryDocument29 pages2002TCPLiving Up ToParentalExpectationInventoryDesiree RamaNo ratings yet

- OutDocument24 pagesOutRose Ann DingalNo ratings yet

- Loneliness and The Feeling of Abandonment, Related To Age, As Factors of Risk To LifeDocument5 pagesLoneliness and The Feeling of Abandonment, Related To Age, As Factors of Risk To LifeIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Parental NarcissismDocument13 pagesParental NarcissismjoaoroxopsicologiaNo ratings yet

- LearningstyleJEEHPDocument7 pagesLearningstyleJEEHPfitri amaliah kasimNo ratings yet

- Selfie Posting and Self-Esteem Among Young Adult Women: A Mediation Model of Positive Feedback and Body SatisfactionDocument12 pagesSelfie Posting and Self-Esteem Among Young Adult Women: A Mediation Model of Positive Feedback and Body SatisfactionWaode SyaifatulNo ratings yet

- Evaluación de La Conducta Adolescente Con Las Escalas de AchenbachDocument8 pagesEvaluación de La Conducta Adolescente Con Las Escalas de AchenbachAndrea MassuchettiNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses of Research On Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory: Constructs and MeasuresDocument18 pagesA Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses of Research On Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory: Constructs and MeasureswqewqewrewNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Adjustment, Decision Making Ability in Relation To Personality of AdolescentsDocument9 pagesAssessment of Adjustment, Decision Making Ability in Relation To Personality of AdolescentsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Dever, B. V. Et Al (2016) - Examining Subtypes of Behavioral-Emotional Risk Using Cluster Analysis.Document5 pagesDever, B. V. Et Al (2016) - Examining Subtypes of Behavioral-Emotional Risk Using Cluster Analysis.saddsa dasdsadsaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Critical Thinking Disposition and Locus of Control in Pre-Service Teachers (Öğretmen Adaylarında Eleştirel Düşünme Eğilimleri Ve Kontol Odağı Arasındaki Il..Document12 pagesThe Relationship Between Critical Thinking Disposition and Locus of Control in Pre-Service Teachers (Öğretmen Adaylarında Eleştirel Düşünme Eğilimleri Ve Kontol Odağı Arasındaki Il..alexNo ratings yet

- Contemplative Neuroscience, Self-Awareness, and Education: Progress in Brain Research January 2019Document32 pagesContemplative Neuroscience, Self-Awareness, and Education: Progress in Brain Research January 2019Renata AndradeNo ratings yet

- Ortega Baron Et Al 2020 Design and Validation of The Brief Self Online Scale So 8 in Early Adolescence An ExploratoryDocument17 pagesOrtega Baron Et Al 2020 Design and Validation of The Brief Self Online Scale So 8 in Early Adolescence An ExploratoryDesi HemavianaNo ratings yet

- Causadias, Salvatore, & Sroufe, 2012Document11 pagesCausadias, Salvatore, & Sroufe, 2012GriselNo ratings yet

- Mahmoudi2015 - The Role of School Culture and Basic Psychological Needs On Iranian Adolescents' Academic AlienationDocument21 pagesMahmoudi2015 - The Role of School Culture and Basic Psychological Needs On Iranian Adolescents' Academic AlienationAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Czopp, Kay, & Cheryan, 2015Document13 pagesCzopp, Kay, & Cheryan, 2015Micaella TimpugNo ratings yet

- Madness and CreativityDocument3 pagesMadness and CreativityEllen LapelNo ratings yet

- Self Concept PaperDocument11 pagesSelf Concept PaperLakshita GomaNo ratings yet

- Dumontheil Wolfe BlakemoreDocument11 pagesDumontheil Wolfe Blakemorediana.pocolNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Framework Exploring Social Media, Eating Disorders, and Body Dissatisfaction Among Latina AdolescentsDocument15 pagesA Conceptual Framework Exploring Social Media, Eating Disorders, and Body Dissatisfaction Among Latina AdolescentsIsmayati PurnamaNo ratings yet

- Why Ineffective Psychotherapies Appear To Work: Perspectives On Psychological Science July 2014Document35 pagesWhy Ineffective Psychotherapies Appear To Work: Perspectives On Psychological Science July 2014Alyson BarrosNo ratings yet

- AcceptVersionCogProfIntellGifted DefDocument47 pagesAcceptVersionCogProfIntellGifted DefsumeyyeNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Properties of The Theory of Mind Assessment Scale in A Sample of Adolescents and AdultsDocument13 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Theory of Mind Assessment Scale in A Sample of Adolescents and AdultsThe English TeacherNo ratings yet

- Does The Number of Response Options Matter? Psychometric Perspectives Using Personality Questionnaire DataDocument12 pagesDoes The Number of Response Options Matter? Psychometric Perspectives Using Personality Questionnaire DataRonnagrit PNo ratings yet

- 318 ArticleText 1903 2 10 20210831Document13 pages318 ArticleText 1903 2 10 20210831Usama SpiffyNo ratings yet

- Comparing Perfectionist Types On Family Environment and Well-Being Among Hong Kong AdolescentsDocument7 pagesComparing Perfectionist Types On Family Environment and Well-Being Among Hong Kong AdolescentsflixrtNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of ArticleDocument7 pagesCritical Analysis of Articleapi-511908080No ratings yet

- Divergent Perceptions Among Internship StakeholdersDocument16 pagesDivergent Perceptions Among Internship StakeholdersCarl Dhaniel Garcia SalenNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Young Children's Compliance To Maternal Directives - A MethanalysisDocument11 pagesGender Differences in Young Children's Compliance To Maternal Directives - A MethanalysisMichelle PajueloNo ratings yet

- The Experiences of Parents WhoDocument228 pagesThe Experiences of Parents WhoMaría GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Educational Stress Scale For Adolescents DevelopmeDocument15 pagesEducational Stress Scale For Adolescents DevelopmeshilpaNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles and Children's Emotional Intelligence: What Do We Know?Document9 pagesParenting Styles and Children's Emotional Intelligence: What Do We Know?Winda CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Emotional Abuse in ChildrenDocument6 pagesEmotional Abuse in Childrenapi-356938005No ratings yet

- Effects of Gender and Thinking Style On Student S Creative Thinking AbilityDocument5 pagesEffects of Gender and Thinking Style On Student S Creative Thinking AbilityAlbert NewtonNo ratings yet

- Adversity Quotient As Correlates To Temperament and Emotional Profile of An Abused Teenager in Manila Boystown ComplexDocument127 pagesAdversity Quotient As Correlates To Temperament and Emotional Profile of An Abused Teenager in Manila Boystown ComplexRichard Cafino GawalaNo ratings yet

- UnderstandDocument163 pagesUnderstandSanty ManuelNo ratings yet

- Problems in Co Education in PakistanDocument6 pagesProblems in Co Education in Pakistansaeedkhan228880% (5)

- Early Child-Parent Attachment and Peer Relations: A Meta-Analysis of Recent ResearchDocument14 pagesEarly Child-Parent Attachment and Peer Relations: A Meta-Analysis of Recent ResearchBrix Untiveros EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Quest To Learn: Developing The School For Digital KidsDocument165 pagesQuest To Learn: Developing The School For Digital KidsThe MIT Press100% (2)

- Digital Harbor Foundation - Strategic Plan - 2019-2021Document20 pagesDigital Harbor Foundation - Strategic Plan - 2019-2021Andrew CoyNo ratings yet

- The Significance of CALLDocument11 pagesThe Significance of CALLapi-343102601No ratings yet

- Module 9 - PROJECT PLANNING - Communication and Stakeholder EngagementDocument6 pagesModule 9 - PROJECT PLANNING - Communication and Stakeholder EngagementJohncel TawatNo ratings yet

- Ethical Guidance For ODDocument11 pagesEthical Guidance For ODDV VillanNo ratings yet

- Maths Implementation ReportDocument6 pagesMaths Implementation Reportapi-265573453No ratings yet

- Career Education 1Document33 pagesCareer Education 1Lorna GabalesNo ratings yet

- Being With OthersDocument18 pagesBeing With OthersBambi IbitNo ratings yet

- Co DLP 1-2022Document7 pagesCo DLP 1-2022Marisor MercadoNo ratings yet

- Presentation GoalsettingtheoryDocument16 pagesPresentation GoalsettingtheorySasNo ratings yet

- Deeply Fully WhollyDocument4 pagesDeeply Fully WhollypilgrimNo ratings yet

- EappDocument39 pagesEappellahNo ratings yet

- Demonstration Teaching in Mapeh 9 Content Standards: The Learner Demonstrate Understanding of The ConceptsDocument6 pagesDemonstration Teaching in Mapeh 9 Content Standards: The Learner Demonstrate Understanding of The ConceptsRacma PanigasNo ratings yet

- Display Blindness: The Effect of Expectations On Attention Towards Digital SignageDocument2 pagesDisplay Blindness: The Effect of Expectations On Attention Towards Digital SignageChristianGuevaraNo ratings yet

- Monir Birouk - Taha Abderrahman's MOral and Spiritual Foundations of Dialogue - 2016Document6 pagesMonir Birouk - Taha Abderrahman's MOral and Spiritual Foundations of Dialogue - 2016yieldsNo ratings yet

- Tuesday: Map Symbols and TitlesDocument6 pagesTuesday: Map Symbols and TitlesNeo SequeiraNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument2 pagesEssaycheNo ratings yet

- OT4a 12. Documentation of Assessment Part of The Initial EvaluationDocument4 pagesOT4a 12. Documentation of Assessment Part of The Initial EvaluationMarianna MessinezisNo ratings yet

- Context, Text Type and TextDocument8 pagesContext, Text Type and TextCristina Maria MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Rezumat in EnglezaDocument2 pagesRezumat in EnglezaBianca DorofteiNo ratings yet

- Sufi Hudaibiah Firmani-FitkDocument42 pagesSufi Hudaibiah Firmani-FitkNurlianaNo ratings yet

- FS1 Ep.9Document4 pagesFS1 Ep.9Rhea Mae ArcigaNo ratings yet

- Scientific Method Graphic OrganizerDocument2 pagesScientific Method Graphic Organizerapi-335094608No ratings yet