Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Project in English 4

Uploaded by

ariannerose06Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Project in English 4

Uploaded by

ariannerose06Copyright:

Available Formats

Project In English IV

Ma. Victoria isidro IV-Apricot Ms.layaog IN THE PIECE OF STRING By Guy de maupassant

ALONG ALL THE ROADS around Goderville the peasants and their wives were coming toward the burgh because it was market day. The men were proceeding with slow steps, the whole body bent forward at each movement of their long twisted legs; deformed by their hard work, by the weight on the plow which, at the same time, raised the left shoulder and swerved the figure, by the reaping of the wheat which made the knees spread to make a firm "purchase," by all the slow and painful labors of the country. Their blouses, blue, "stiffstarched," shining as if varnished, ornamented with a little design in white at the neck and wrists, puffed about their bony bodies, seemed like balloons ready to carry them off. From each of them two feet protruded. Some led a cow or a calf by a cord, and their wives, walking behind the animal, whipped its haunches with a leafy branch to hasten its progress. They carried large baskets on their arms from which, in some cases, chickens and, in others, ducks thrust out their heads. And they walked with a quicker, livelier step than their husbands. Their spare straight figures were wrapped in a scanty little shawl pinned over their flat bosoms, and their heads were enveloped in a white cloth glued to the hair and surmounted by a cap. Then a wagon passed at the jerky trot of a nag, shaking strangely, two men seated side by side and a woman in the bottom of the vehicle, the latter holding onto the sides to lessen the hard jolts. In the public square of Goderville there was a crowd, a throng of human beings and animals mixed together. The horns of the cattle, the tall hats, with long nap, of the rich peasant and the headgear of the peasant women rose above the surface of the assembly. And the clamorous, shrill, screaming voices made a continuous and savage din which sometimes was dominated by the robust lungs of some countryman's laugh or the long lowing of a cow tied to the wall of a house. All that smacked of the stable, the dairy and the dirt heap, hay and sweat, giving forth that unpleasant odor, human and animal, peculiar to the people of the field. Matre Hauchecome of Breaute had just arrived at Goderville, and he was directing his steps toward the public square when he perceived upon the ground a little piece of string. Matre

Hauchecome, economical like a true Norman, thought that everything useful ought to be picked up, and he bent painfully, for he suffered from rheumatism. He took the bit of thin cord from the ground and began to roll it carefully when he noticed Matre Malandain, the harness maker, on the threshold of his door, looking at him. They had heretofore had business together on the subject of a halter, and they were on bad terms, both being good haters. Matre Hauchecome was seized with a sort of shame to be seen thus by his enemy, picking a bit of string out of the dirt. He concealed his "find" quickly under his blouse, then in his trousers' pocket; then he pretended to be still looking on the ground for something which he did not find, and he went toward the market, his head forward, bent double by his pains. He was soon lost in the noisy and slowly moving crowd which was busy with interminable bargainings. The peasants milked, went and came, perplexed, always in fear of being cheated, not daring to decide, watching the vender's eye, ever trying to find the trick in the man and the flaw in the beast. The women, having placed their great baskets at their feet, had taken out the poultry which lay upon the ground, tied together by the feet, with terrified eyes and scarlet crests. They heard offers, stated their prices with a dry air and impassive face, or perhaps, suddenly deciding on some proposed reduction, shouted to the customer who was slowly going away: "All right, Matre Authirne, I'll give it to you for that." Then lime by lime the square was deserted, and the Angelus ringing at noon, those who had stayed too long scattered to their shops. At Jourdain's the great room was full of people eating, as the big court was full of vehicles of all kinds, carts, gigs, wagons, dumpcarts, yellow with dirt, mended and patched, raising their shafts to the sky like two arms or perhaps with their shafts in the ground and their backs in the air. Just opposite the diners seated at the table the immense fireplace, filled with bright flames, cast a lively heat on the backs of the row on the right. Three spits were turning on which

were chickens, pigeons and legs of mutton, and an appetizing odor of roast beef and gravy dripping over the nicely browned skin rose from the hearth, increased the jovialness and made everybody's mouth water. All the aristocracy of the plow ate there at Matre Jourdain's, tavern keeper and horse dealer, a rascal who had money. The dishes were passed and emptied, as were the jugs of yellow cider. Everyone told his affairs, his purchases and sales. They discussed the crops. The weather was favorable for the green things but not for the wheat. Suddenly the drum beat in the court before the house. Everybody rose, except a few indifferent persons, and ran to the door or to the windows, their mouths still full and napkins in their hands. After the public crier had ceased his drumbeating he called out in a jerky voice, speaking his phrases irregularly: "It is hereby made known to the inhabitants of Goderville, and in general to all persons present at the market, that there was lost this morning on the road to Benzeville, between nine and ten o'clock, a black leather pocketbook containing five hundred francs and some business papers. The finder is requested to return same with all haste to the mayor's office or to Matre Fortune Houlbreque of Manneville; there will be twenty francs reward." Then the man went away. The heavy roll of the drum and the crier's voice were again heard at a distance. Then they began to talk of this event, discussing the chances that Matre Houlbreque had of finding or not finding his pocketbook. And the meal concluded. They were finishing their coffee when a chief of the gendarmes appeared upon the threshold. He inquired: "Is Matre Hauchecome of Breaute here?" Matre Hauchecome, seated at the other end of the table, replied:

"Here I am." And the officer resumed: "Matre Hauchecome, will you have the goodness to accompany me to the mayor's office? The mayor would like to talk to you." The peasant, surprised and disturbed, swallowed at a draught his tiny glass of brandy, rose and, even more bent than in the morning, for the first steps after each rest were specially difficult, set out, repeating: "Here I am, here I am." The mayor was awaiting him, seated on an armchair. He was the notary of the vicinity, a stout, serious man with pompous phrases. "Matre Hauchecome," said he, "you were seen this morning to pick up, on the road to Benzeville, the pocketbook lost by Matre Houlbreque of Manneville." The countryman, astounded, looked at the mayor, already terrified by this suspicion resting on him without his knowing why. "Me? Me? Me pick up the pocketbook?" "Yes, you yourself." "Word of honor, I never heard of it." "But you were seen." "I was seen, me? Who says he saw me?" "Monsieur Malandain, the harness maker." The old man remembered, understood and flushed with anger. "Ah, he saw me, the clodhopper, he saw me pick up this string here, M'sieu the Mayor." And rummaging in his pocket, he drew out the little piece of string. But the mayor, incredulous, shook his head. "You will not make me believe, Matre Hauchecome, that Monsieur Malandain, who is a man worthy of credence, mistook this cord for a pocketbook."

The peasant, furious, lifted his hand, spat at one side to attest his honor, repeating: "It is nevertheless the truth of the good God, the sacred truth, M'sieu the Mayor. I repeat it on my soul and my salvation." The mayor resumed: "After picking up the object you stood like a stilt, looking a long while in the mud to see if any piece of money had fallen out." The good old man choked with indignation and fear. "How anyone can tell--how anyone can tell--such lies to take away an honest man's reputation! How can anyone---" There was no use in his protesting; nobody believed him. He was con. fronted with Monsieur Malandain, who repeated and maintained his affirmation. They abused each other for an hour. At his own request Matre Hauchecome was searched; nothing was found on him. Finally the mayor, very much perplexed, discharged him with the warning that he would consult the public prosecutor and ask for further orders. The news had spread. As he left the mayor's office the old man was sun rounded and questioned with a serious or bantering curiosity in which there was no indignation. He began to tell the story of the string. No one believed him. They laughed at him. He went along, stopping his friends, beginning endlessly his statement and his protestations, showing his pockets turned inside out to prove that he had nothing. They said: "Old rascal, get out!" And he grew angry, becoming exasperated, hot and distressed at not

being believed, not knowing what to do and always repeating himself. Night came. He must depart. He started on his way with three neighbors to whom he pointed out the place where he had picked up the bit of string, and all along the road he spoke of his adventure. In the evening he took a turn in the village of Breaute in order to tell it to everybody. He only met with incredulity. It made him ill at night. The next day about one o'clock in the afternoon Marius Paumelle, a hired man in the employ of Matre Breton, husbandman at Ymanville, returned the pocketbook and its contents to Matre Houlbreque of Manneville. This man claimed to have found the object in the road, but not knowing how to read, he had carried it to the house and given it to his employer. The news spread through the neighborhood. Matre Hauchecome was informed of it. He immediately went the circuit and began to recount his story completed by the happy climax. He was in triumph. "What grieved me so much was not the thing itself as the lying. There is nothing so shameful as to be placed under a cloud on account of a lie." He talked of his adventure all day long; he told it on the highway to people who were passing by, in the wineshop to people who were drinking there and to persons coming out of church the following Sunday. He stopped strangers to tell them about it. He was calm now, and yet something disturbed him without his knowing exactly what it was. People had the air of joking while they listened. They did not seem convinced. He seemed to feel that remarks were being made behind his back. On Tuesday of the next week he went to the market at Goderville, urged solely by the necessity he felt of discussing the case.

Malandain, standing at his door, began to laugh on seeing him pass. Why? He approached a farmer from Crequetot who did not let him finish and, giving him a thump in the stomach, said to his face: "You big rascal." Then he turned his back on him. Matre Hauchecome was confused; why was he called a big rascal? When he was seated at the table in Jourdain's tavern he commenced to explain "the affair." A horse dealer from Monvilliers called to him: "Come, come, old sharper, that's an old trick; I know all about your piece of string!" Hauchecome stammered: "But since the pocketbook was found." But the other man replied: "Shut up, papa, there is one that finds and there is one that reports. At any rate you are mixed with it." The peasant stood choking. He understood. They accused him of having had the pocketbook returned by a confederate, by an accomplice. He tried to protest. All the table began to laugh. He could not finish his dinner and went away in the midst of jeers. He went home ashamed and indignant, choking with anger and confusion, the more dejected that he was capable, with his Norman cunning, of doing what they had accused him of and ever boasting of it as of a good turn. His innocence to him, in a

confused way, was impossible to prove, as his sharpness was known. And he was stricken to the heart by the injustice of the suspicion. Then he began to recount the adventures again, prolonging his history every day, adding each time new reasons, more energetic protestations, more solemn oaths which he imagined and prepared in his hours of solitude, his whole mind given up to the story of the string. He was believed so much the less as his defense was more complicated and his arguing more subtile. "Those are lying excuses," they said behind his back. He felt it, consumed his heart over it and wore himself out with useless efforts. He wasted away before their very eyes. The wags now made him tell about the string to amuse them, as they make a soldier who has been on a campaign tell about his battles. His mind, touched to the depth, began to weaken. Toward the end of December he took to his bed. He died in the first days of January, and in the delirium of his death struggles he kept claiming his innocence, reiterating: "A piece of string, a piece of string--look--here it is, M'sieu the Mayor."

Biography of GUY DE MAUPASSANT

Henri-Ren-Albert-Guy de Maupassant was born on August 5, 1850 at the chteau de Miromesnil, near Dieppe in the SeineInfrieure (now Seine-Maritime) department. He was the first son of Laure Le Poittevin and Gustave de Maupassant, both from prosperous bourgeois families. When Maupassant was eleven and his brother Herv was five, his mother, an independentminded woman, risked social disgrace to obtain a legal separation from her husband. After the separation, Le Poittevin kept her two sons, the elder Guy and younger Herv. With the fathers absence, Maupassants mother became the most influential figure in the young boys life. She was an exceptionally well read woman and was very fond of classical literature, especially Shakespeare. Until the age of thirteen, Guy happily lived with his mother, to whom he was deeply devoted, at tretat, in the Villa des Verguies, where, between the sea and the luxuriant

countryside, he grew very fond of fishing and outdoor activities. At age thirteen, he was sent to a small seminary near Rouen for classical studies. In October 1868, at the age of 18, he saved the famous poet Algernon Charles Swinburne from drowning off the coast of tretat at Normandy.[2] As he entered junior high school, he met the great author Gustave Flaubert. He first entered a seminary at Yvetot, but deliberately got himself expelled. From his early education he retained a marked hostility to religion. Then he was sent to the Lyce PierreCorneille in Rouen[3] where he proved a good scholar indulging in poetry and taking a prominent part in theatricals. The Franco-Prussian War broke out soon after his graduation from college in 1870; he enlisted as a volunteer and fought bravely. Afterwards, in 1871, he left Normandy and moved to Paris where he spent ten years as a clerk in the Navy Department. During these ten tedious years his only recreation and relaxation was canoeing on the Seine on Sundays and holidays. Gustave Flaubert took him under his protection and acted as a kind of literary guardian to him, guiding his debut in journalism and literature. At Flaubert's home he met mile Zola and the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, as well as many of the proponents of the realist and naturalist schools. In 1878 he was transferred to the Ministry of Public Instruction and became a contributing editor of several leading newspapers such as Le Figaro, Gil Blas, Le Gaulois and l'cho de Paris. He devoted his spare time to writing novels and short stories. In 1880 he published what is considered his first masterpiece, "Boule de Suif", which met with an instant and tremendous success. Flaubert characterized it as "a masterpiece that will endure." This was Maupassant's first piece of short fiction set during the Franco-Prussian War, and was followed by short stories such as "Deux Amis", "Mother Savage", and "Mademoiselle Fifi". The decade from 1880 to 1891 was the most fertile period of Maupassant's life. Made famous by his first short story, he worked methodically and produced two or sometimes four

volumes annually. He combined talent and practical business sense, which made him wealthy. In 1881 he published his first volume of short stories under the title of La Maison Tellier; it reached its twelfth edition within two years; in 1883 he finished his first novel, Une Vie (translated into English as A Woman's Life), 25,000 copies of which were sold in less than a year. In his novels, he concentrated all his observations scattered in his short stories. His second novel Bel-Ami, which came out in 1885, had thirtyseven printings in four months. His editor, Havard, commissioned him to write new masterpieces and Maupassant continued to produce them without the slightest apparent effort. At this time he wrote what many consider to be his greatest novel, Pierre et Jean. With a natural aversion to society, he loved retirement, solitude, and meditation. He traveled extensively in Algeria, Italy, England, Brittany, Sicily, Auvergne, and from each voyage brought back a new volume. He cruised on his private yacht "Bel-Ami," named after his earlier novel. This feverish life did not prevent him from making friends among the literary celebrities of his day: Alexandre Dumas, fils had a paternal affection for him; at Aix-les-Bains he met Hippolyte Taine and fell under the spell of the philosopher-historian. Flaubert continued to act as his literary godfather. His friendship with the Goncourts was of short duration; his frank and practical nature reacted against the ambience of gossip, scandal, duplicity, and invidious criticism that the two brothers had created around them in the guise of an 18th-century style salon. Maupassant was but one of a fair number of 19th-century Parisians who did not care for the Eiffel tower; indeed, he often ate lunch in the restaurant at its base, not out of any preference for the food, but because it was only there that he could avoid seeing its otherwise unavoidable profile.[4] Moreover, he and forty-six other Parisian literary and artistic notables attached their names to letter of protest, ornate as it was irate, against the tower's construction to the then Minister of Public Works.[5]

Maupassant also wrote under several pseudonyms such as Joseph Prunier, Guy de Valmont, and Maufrigneuse (which he used from 1881 to 1885). In his later years he developed a constant desire for solitude, an obsession for self-preservation, and a fear of death and crazed paranoia of persecution, that came from the syphilis he had contracted in his early days. On January 2, in 1892, Maupassant tried to commit suicide by cutting his throat and was committed to the celebrated private asylum of Dr. Esprit Blanche at Passy, in Paris, where he died on July 6, 1893. Guy De Maupassant penned his own epitaph: "I have coveted everything and taken pleasure in nothing." He is buried in Section 26 of the Cimetire du Montparnasse, Paris. Significance Maupassant is considered one of the fathers of the modern short story. He delighted in clever plotting, and served as a model for Somerset Maugham and O. Henry in this respect. His stories about expensive jewelry ("The Necklace", "Les Bijoux") are imitated with a twist by Maugham ("Mr Know-All", "A String of Beads") and Henry James. Taking his cue from Balzac, Maupassant wrote comfortably in both the high-Realist and fantastic modes; stories and novels such as "L'Hritage" and Bel-Ami aim to recreate Third Republic France in a realistic way, whereas many of the short stories (notably "Le Horla" and "Qui sait ?") describe apparently supernatural phenomena. The supernatural in Maupassant, however, is often implicitly a symptom of the protagonists' troubled minds; Maupassant was fascinated by the burgeoning discipline of psychiatry, and attended the public lectures of Jean-Martin Charcot between 1885 and 1886.[6] This interest is reflected in his fiction. Criticism Maupassant is notable as the subject of one of Leo Tolstoy's essays on art: The Works of Guy de Maupassant. Friedrich Nietzsche's autobiography mentions him in the following text:

"I cannot at all conceive in which century of history one could haul together such inquisitive and at the same time delicate psychologists as one can in contemporary Paris: I can name as a sample for their number is by no means small, ... or to pick out one of the stronger race, a genuine Latin to whom I am particularly attached, Guy de Maupassant."

IN THE TELL-TALE HEART BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

TRUE! --nervous --very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses --not destroyed --not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then,

am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily --how calmly I can tell you the whole story. It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture --a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees --very gradually --I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever. Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded --with what caution --with what foresight --with what dissimulation I went to work! I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him. And every night, about midnight, I turned the latch of his door and opened it --oh so gently! And then, when I had made an opening sufficient for my head, I put in a dark lantern, all closed, closed, that no light shone out, and then I thrust in my head. Oh, you would have laughed to see how cunningly I thrust it in! I moved it slowly --very, very slowly, so that I might not disturb the old man's sleep. It took me an hour to place my whole head within the opening so far that I could see him as he lay upon his bed. Ha! would a madman have been so wise as this, And then, when my head was well in the room, I undid the lantern cautiously-oh, so cautiously --cautiously (for the hinges creaked) --I undid it just so much that a single thin ray fell upon the vulture eye. And this I did for seven long nights --every night just at midnight --but I found the eye always closed; and so it was impossible to do the work; for it was not the old man who vexed me, but his Evil Eye. And every morning, when the day broke, I went boldly into the chamber, and spoke courageously to him, calling him by name in a hearty tone, and inquiring how he has passed the night. So you see he would have been a very profound old man, indeed, to suspect that every night, just at twelve, I looked in upon him while he slept. Upon the eighth night I was more than usually cautious in opening the door. A watch's minute hand moves more quickly than did mine. Never before that night had I felt the extent of my own powers --of my sagacity. I could scarcely contain my

feelings of triumph. To think that there I was, opening the door, little by little, and he not even to dream of my secret deeds or thoughts. I fairly chuckled at the idea; and perhaps he heard me; for he moved on the bed suddenly, as if startled. Now you may think that I drew back --but no. His room was as black as pitch with the thick darkness, (for the shutters were close fastened, through fear of robbers,) and so I knew that he could not see the opening of the door, and I kept pushing it on steadily, steadily. I had my head in, and was about to open the lantern, when my thumb slipped upon the tin fastening, and the old man sprang up in bed, crying out --"Who's there?" I kept quite still and said nothing. For a whole hour I did not move a muscle, and in the meantime I did not hear him lie down. He was still sitting up in the bed listening; --just as I have done, night after night, hearkening to the death watches in the wall. Presently I heard a slight groan, and I knew it was the groan of mortal terror. It was not a groan of pain or of grief --oh, no! --it was the low stifled sound that arises from the bottom of the soul when overcharged with awe. I knew the sound well. Many a night, just at midnight, when all the world slept, it has welled up from my own bosom, deepening, with its dreadful echo, the terrors that distracted me. I say I knew it well. I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him, although I chuckled at heart. I knew that he had been lying awake ever since the first slight noise, when he had turned in the bed. His fears had been ever since growing upon him. He had been trying to fancy them causeless, but could not. He had been saying to himself --"It is nothing but the wind in the chimney --it is only a mouse crossing the floor," or "It is merely a cricket which has made a single chirp." Yes, he had been trying to comfort himself with these suppositions: but he had found all in vain. All in vain; because Death, in approaching him had stalked with his black shadow before him, and enveloped the victim. And it was the mournful influence of the unperceived shadow that caused him to feel --although he neither saw nor heard --to feel the presence of my head within the room. When I had waited a long time, very patiently, without hearing him lie down, I resolved to open a little --a very, very little

crevice in the lantern. So I opened it --you cannot imagine how stealthily, stealthily --until, at length a simple dim ray, like the thread of the spider, shot from out the crevice and fell full upon the vulture eye. It was open --wide, wide open --and I grew furious as I gazed upon it. I saw it with perfect distinctness --all a dull blue, with a hideous veil over it that chilled the very marrow in my bones; but I could see nothing else of the old man's face or person: for I had directed the ray as if by instinct, precisely upon the damned spot. And have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but over-acuteness of the sense? --now, I say, there came to my ears a low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I knew that sound well, too. It was the beating of the old man's heart. It increased my fury, as the beating of a drum stimulates the soldier into courage. But even yet I refrained and kept still. I scarcely breathed. I held the lantern motionless. I tried how steadily I could maintain the ray upon the eve. Meantime the hellish tattoo of the heart increased. It grew quicker and quicker, and louder and louder every instant. The old man's terror must have been extreme! It grew louder, I say, louder every moment! --do you mark me well I have told you that I am nervous: so I am. And now at the dead hour of the night, amid the dreadful silence of that old house, so strange a noise as this excited me to uncontrollable terror. Yet, for some minutes longer I refrained and stood still. But the beating grew louder, louder! I thought the heart must burst. And now a new anxiety seized me --the sound would be heard by a neighbour! The old man's hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once --once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eve would trouble me no more.

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs. I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eye --not even his --could have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash out --no stain of any kind --no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught all --ha! ha! When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clock --still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart, --for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises. I smiled, --for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search --search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim. The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears: but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct: --It continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definiteness --until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale; --but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased --and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound --much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath --and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly --more vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men --but the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what could I do? I foamed --I raved --I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder --louder --louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God! --no, no! They heard! --they suspected! --they knew! --they were making a mockery of my horror!-this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! and now --again! --hark! louder! louder! louder! louder! "Villains!" I shrieked, "dissemble no more! I admit the deed! --tear up the planks! here, here! --It is the beating of his hideous heart!" -THE END-

BiOGRAPHY OF EDGAR ALLAN POE

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809 October 7, 1849) was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction.[1] He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.[2] He was born as Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts; he was orphaned young when his mother died shortly after his father abandoned the family. Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan, of Richmond, Virginia, but they never formally adopted him. He attended the University of Virginia for one semester but left due to lack of money. After enlisting in the Army and later failing as an officer's cadet at West Point, Poe parted ways with the Allans. His publishing career began humbly, with an

anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to "a Bostonian". Poe switched his focus to prose and spent the next several years working for literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of literary criticism. His work forced him to move among several cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. In Baltimore in 1835, he married Virginia Clemm, his 13-year-old cousin. In January 1845 Poe published his poem, "The Raven", to instant success. His wife died of tuberculosis two years after its publication. He began planning to produce his own journal, The Penn (later renamed The Stylus), though he died before it could be produced. On October 7, 1849, at age 40, Poe died in Baltimore; the cause of his death is unknown and has been variously attributed to alcohol, brain congestion, cholera, drugs, heart disease, rabies, suicide, tuberculosis, and other agents.[3] Poe and his works influenced literature in the United States and around the world, as well as in specialized fields, such as cosmology and cryptography. Poe and his work appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. A number of his homes are dedicated museums today.

characters

The main character here in this story is MAITRE HAUCHECOME,economical,like a true Norman.He is very thrifty.He is very practical person.For him,everything that is still benificiable must be picked up or must be kept.He is the one who accused as the stealer of the leather pocketbook containing five hundred francs and some business papers. He did his best

You might also like

- 1 Le Tabac Vert Green TobaccoDocument23 pages1 Le Tabac Vert Green Tobaccoecriture67% (3)

- Literary Analysis: The Wolf by Guy de Mauppassant: ChaseDocument3 pagesLiterary Analysis: The Wolf by Guy de Mauppassant: ChaseDeirdre DizonNo ratings yet

- The Piece of StringDocument5 pagesThe Piece of StringJOHN EDSEL CERBASNo ratings yet

- A Piece of String by Guy de MaupassantDocument6 pagesA Piece of String by Guy de MaupassantHoneyNo ratings yet

- The Piece of String Plot AnalysisDocument10 pagesThe Piece of String Plot Analysismaricon elleNo ratings yet

- The Piece of StringDocument4 pagesThe Piece of StringJeral Mae DabuNo ratings yet

- Guy de Maupassant's "A Piece of StringDocument9 pagesGuy de Maupassant's "A Piece of StringAndrea Cruz ChamorroNo ratings yet

- A Piece of StringDocument5 pagesA Piece of Stringmain.rebecca.bumalayNo ratings yet

- Undefined Undefined: Exposition: It Was Market-Day, and From All The Country Round Goderville The Peasants and TheirDocument3 pagesUndefined Undefined: Exposition: It Was Market-Day, and From All The Country Round Goderville The Peasants and TheirAnthony ChanNo ratings yet

- The Pied Piper HamelinDocument21 pagesThe Pied Piper HamelinjohnacresNo ratings yet

- The Honor of The Name by Gaboriau, Émile, 1832-1873Document367 pagesThe Honor of The Name by Gaboriau, Émile, 1832-1873Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- THE COUNT'S MILLIONS: Pascal and Marguerite & Baron Trigault's Vengeance - Historical Mystery NovelsFrom EverandTHE COUNT'S MILLIONS: Pascal and Marguerite & Baron Trigault's Vengeance - Historical Mystery NovelsNo ratings yet

- The Plébiscite; or, A Miller's Story of the War: By One of the 7,500,000 Who Voted "Yes"From EverandThe Plébiscite; or, A Miller's Story of the War: By One of the 7,500,000 Who Voted "Yes"No ratings yet

- A Piece of Stri WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesA Piece of Stri WPS OfficeStephanie BanzuelaNo ratings yet

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin, and Other Poems: Every Boy's LibraryFrom EverandThe Pied Piper of Hamelin, and Other Poems: Every Boy's LibraryNo ratings yet

- Dr. Massarel Declares Republic in Small French TownDocument7 pagesDr. Massarel Declares Republic in Small French TownPaula JatzNo ratings yet

- Vadriel Vail - Vincent VirgaDocument382 pagesVadriel Vail - Vincent Virganatsudragneel1967No ratings yet

- The Complete Poetical Works: Hermann and Dorothea, Reynard the Fox, The Sorcerer's Apprentice, Ballads, Epigrams, Parables, Elegies and many moreFrom EverandThe Complete Poetical Works: Hermann and Dorothea, Reynard the Fox, The Sorcerer's Apprentice, Ballads, Epigrams, Parables, Elegies and many moreNo ratings yet

- Pied Piper of HamelinDocument28 pagesPied Piper of HamelinSermuga PandianNo ratings yet

- Bel Ami (A Ladies' Man) The Works of Guy de Maupassant, Vol. 6From EverandBel Ami (A Ladies' Man) The Works of Guy de Maupassant, Vol. 6No ratings yet

- Within An Inch of His Life by Gaboriau, Émile, 1832-1873Document352 pagesWithin An Inch of His Life by Gaboriau, Émile, 1832-1873Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Woolf Virginia The Duchess and The JewellerDocument8 pagesWoolf Virginia The Duchess and The Jewellerია თურმანიძეNo ratings yet

- EloquentpeasantDocument3 pagesEloquentpeasantBlackpool123 KickassNo ratings yet

- Stories of The Fool: Tony's Scrap Book: 1937-38 EditionDocument4 pagesStories of The Fool: Tony's Scrap Book: 1937-38 EditionDusty DealNo ratings yet

- The Adopted SonDocument7 pagesThe Adopted SonNaishika VadakattuNo ratings yet

- 22 The Sea Still RisesDocument6 pages22 The Sea Still RisesBojanNo ratings yet

- The Mayor of GantickDocument4 pagesThe Mayor of GantickaravindpunnaNo ratings yet

- An Affair of StateDocument6 pagesAn Affair of StateSimran OberoiNo ratings yet

- The Man in The High-Water Boots1909 by Smith, F. HopkinsonDocument16 pagesThe Man in The High-Water Boots1909 by Smith, F. HopkinsonGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Clever Tales (1897) by Charlotte Potter & Hele ClarkeDocument254 pagesClever Tales (1897) by Charlotte Potter & Hele Clarkeioannis zezasNo ratings yet

- Upton Sinclair - The JungleDocument333 pagesUpton Sinclair - The Junglefulai100% (1)

- Sac-Au-Dos1907 by Huysmans, J.-K. (Joris-Karl), 1848-1907Document24 pagesSac-Au-Dos1907 by Huysmans, J.-K. (Joris-Karl), 1848-1907Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Project Gutenberg E-Text of Bel Ami, by Guy de MaupassantDocument212 pagesThe Project Gutenberg E-Text of Bel Ami, by Guy de MaupassantKhishig JargalNo ratings yet

- How a vagabond's idea of the world as a trap led to his own downfallDocument10 pagesHow a vagabond's idea of the world as a trap led to his own downfallAdil HossainNo ratings yet

- Table of ContentsDocument1 pageTable of Contentsariannerose06No ratings yet

- MyanmarDocument3 pagesMyanmarariannerose06No ratings yet

- MyanmarDocument3 pagesMyanmarariannerose06No ratings yet

- EthicsDocument9 pagesEthicsariannerose06No ratings yet

- Taximan's StoryDocument1 pageTaximan's Storyariannerose06No ratings yet

- Activity NoDocument3 pagesActivity Noariannerose06No ratings yet

- Religion IIDocument2 pagesReligion IIariannerose06No ratings yet

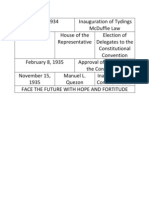

- Phil ConstitutionDocument1 pagePhil Constitutionariannerose06No ratings yet

- SPO PsychDocument3 pagesSPO Psychariannerose06No ratings yet

- Periodic Table of ElementsDocument6 pagesPeriodic Table of Elementsariannerose06No ratings yet

- Prostatic NCPDocument24 pagesProstatic NCPariannerose06No ratings yet

- Prostatic NCPDocument24 pagesProstatic NCPariannerose06No ratings yet

- NCP 1Document3 pagesNCP 1ariannerose06No ratings yet

- Standing Order SheetDocument2 pagesStanding Order Sheetariannerose06No ratings yet

- Assignment in EnglishIVDocument4 pagesAssignment in EnglishIVariannerose06No ratings yet

- CapsuleDocument2 pagesCapsuleariannerose06No ratings yet

- Hirschsprung Diet CowsmilkDocument3 pagesHirschsprung Diet Cowsmilkariannerose06No ratings yet

- Guy de Maupassant ThesisDocument4 pagesGuy de Maupassant ThesisAngie Miller100% (2)

- Moonlight by MaupassantDocument8 pagesMoonlight by MaupassantJes EstacionNo ratings yet

- The Necklace (Guy de Maupassant)Document4 pagesThe Necklace (Guy de Maupassant)Crizzel Mae ManingoNo ratings yet

- The Piece of StringDocument13 pagesThe Piece of StringMuhammad FaizanNo ratings yet

- Guy de MaupassantDocument9 pagesGuy de MaupassantJabin Sta. TeresaNo ratings yet

- Lit 2 Module 5Document6 pagesLit 2 Module 5Bernard Jayve PalmeraNo ratings yet

- Eng PTDocument5 pagesEng PTMikaela FabrosNo ratings yet

- The NECKLACE by Guy de Maupassant A CritDocument9 pagesThe NECKLACE by Guy de Maupassant A CritMaricel CondemelicorNo ratings yet

- At Sea Guy de MaupassantDocument14 pagesAt Sea Guy de MaupassantMhel RillonNo ratings yet

- The JewelsDocument9 pagesThe Jewelsapi-367990381100% (1)

- Guy de Maupassant's The Horla AnalysisDocument2 pagesGuy de Maupassant's The Horla AnalysisBea BonitaNo ratings yet

- The Necklace EssayDocument3 pagesThe Necklace EssaySachi pimentelNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Fantastique Le HorlaDocument6 pagesDissertation Fantastique Le HorlaWriteMyPaperKansasCity100% (1)

- The Necklace: Intr OductionDocument16 pagesThe Necklace: Intr OductionAjannakaNo ratings yet

- Guy de Maupassant - WikipediaDocument1 pageGuy de Maupassant - WikipediapbmvjnNo ratings yet

- By Guy de Maupassant: MoonlightDocument41 pagesBy Guy de Maupassant: MoonlightMary Rose Mendoza100% (1)

- English Paper IIIDocument92 pagesEnglish Paper IIIKannamaniNo ratings yet

- Sacrifice ThesisDocument105 pagesSacrifice ThesisMAHAD ZahidNo ratings yet

- Realism in FranceDocument8 pagesRealism in Francealfredo_ferrari_5No ratings yet

- Necklace: by Guy de MaupassantDocument17 pagesNecklace: by Guy de MaupassantJustin Lee Santos100% (1)

- Guy de Maupassant Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesGuy de Maupassant Thesis Statementafknbiwol100% (2)

- Two Little SoldiersDocument13 pagesTwo Little Soldiersjune0% (1)

- La Normandie Chez MaupassantDocument96 pagesLa Normandie Chez MaupassantRIDA ELBACHIR100% (1)

- Two Little SoldiersDocument10 pagesTwo Little Soldiersprask7871No ratings yet

- Guy de MaupassantDocument8 pagesGuy de MaupassantRohayu -0% (1)

- Flaubert Mau Pass 00 RiddDocument134 pagesFlaubert Mau Pass 00 RiddleocoutoNo ratings yet

- Guy de Maupassant, master of the short storyDocument7 pagesGuy de Maupassant, master of the short storyMaham SheikhNo ratings yet

- Book ReportDocument14 pagesBook ReportYeny XDNo ratings yet

- Author Guy de Maupassant Biography Reading ComprehensionDocument4 pagesAuthor Guy de Maupassant Biography Reading ComprehensionBraeden CulpNo ratings yet