0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views10 pagesA Tale of Two Cities PDF

A Tale of Two Cities is set in London and Paris in the late 18th century during the French Revolution. In the first book, Dr. Alexandre Manette is released from the Bastille prison in Paris after 18 years of imprisonment. His daughter Lucie travels from London to Paris with Mr. Jarvis Lorry and is reunited with her father. In the second book, Charles Darnay is on trial for treason in London but is acquitted after witnesses testify on his behalf. In Paris, Darnay renounces his aristocratic inheritance. In the third book, Darnay is imprisoned during the Revolution and faces execution. Lucie, Dr. Manette, and others travel to Paris to try to

Uploaded by

exam purposeCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views10 pagesA Tale of Two Cities PDF

A Tale of Two Cities is set in London and Paris in the late 18th century during the French Revolution. In the first book, Dr. Alexandre Manette is released from the Bastille prison in Paris after 18 years of imprisonment. His daughter Lucie travels from London to Paris with Mr. Jarvis Lorry and is reunited with her father. In the second book, Charles Darnay is on trial for treason in London but is acquitted after witnesses testify on his behalf. In Paris, Darnay renounces his aristocratic inheritance. In the third book, Darnay is imprisoned during the Revolution and faces execution. Lucie, Dr. Manette, and others travel to Paris to try to

Uploaded by

exam purposeCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

- Introduction

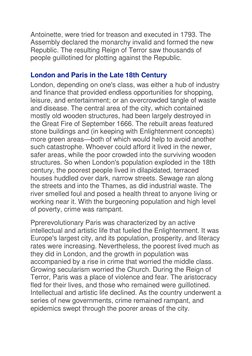

- Historical Context

- Summary and Book Content

- Characters