Professional Documents

Culture Documents

"Young Malinowski and His Later Years

Uploaded by

Museu da MOOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

"Young Malinowski and His Later Years

Uploaded by

Museu da MOCopyright:

Available Formats

comments and reflections

young Malinowski and his later years

FELIKS GROSS-Brooklyn College, CUNY

This essay is a revised version of a talk at Barnard College, 23 April 1985. We wish to thank

loan Vincent and Morton Klass for their part in organizing this occasion. Feliks Gross, Emeritus

Professor at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, is director of the Polish lnstitute

of Arts and Sciences of America.

Let me begin with a question. Is it entirely coincidental that in the same city of Cracow,

divided only by a single generation, two men, JosephConrad and Bronislaw Malinowski, had

an impact on both British and world culture? Let me tell you briefly the story of both as I see it,

and I shall try to comment on this question.

Joseph Conrad came from eastern Poland and studied at St. Anna Gymnazium in Cracow,

which my father attended at about the same time or only a few years later. Conrad received a

classical education in Latin and Greek, but did not finish, if I remember correctly. Bronislaw

Malinowski went to another gymnazium, Sobieski, where I was a student. Although we were

divided by two academic generations, we had some of the same professors. At the university I

knew personally Professor Wladyslaw Heinrich, philosopher and psychologist; Malinowski

was his student and respected him highly.

Malinowski and Conrad were from similar backgrounds. They were both from the gentry,

which had a tradition of national independence and liberty. After the partition of Poland, every

generation mounted an uprising or an insurrection against the Russian conquerors, and every

insurrection was lost, From Conrad’s Personal Record it seems that his generation was tired of

hopeless struggles that ended in defeat. But that was the nature of the national tradition at that

time, that the insurrection had to be mounted even if it was defeated.

When speaking of Conrad and Malinowski, it is perhaps proper to tell something about the

historical context. Polish political emigration to France began early in the 18th century, and by

the 19th century political exiles went also to England. From the 14th century on (perhapseven

earlier), Polish students were already in Bologna and in other Italian universities. In the 15th

century, Copernicus, a student from the University of Cracow, was teaching in Italy, and many

other Polish scholars were dispersed throughout Europe. Now, the Poles who emigrated to

France during the French Revolution joined the army, and a Polish Legion was later formed

that fought under Bonaparte. The Polish literature that developed a generation later included

poets such as Mickiewicz and Slowacki, who settled in France; their poetry was not inferior to

that of Pushkin, and they had a wide audience, primarily, perhaps, among the Poles, and they

remained national poets.

Both Conrad and Malinowski, however, were absorbed by British culture in a way that the

others were not absorbed by French culture. The French did not have this quality of cultural

fusion. There is a continuity of Polish presence in France, but the immigrants, at least for a

generation or two, remained a Polish colony. In England, on the other hand, Conrad’s and

Malinowski’s work became a part of British culture. Why? I have only a tentative suggestion.

556 american ethnologist

Those who were in France spoke above all to the Poles, appealed to longings and sentiments

that were shared by them. They wrote for them. Both Malinowski and Conrad, however,

touched on what is universal in mankind. They could identify with the universal elements in

British culture and with the universal elements in world culture. Moreover, neither Conrad nor

Malinowski were alone. There were others, especially the descendants of the insurrection of

1831 (amongthem Stokowski and Gielgud) who had settled in England. This is a part of Polish

history that is less known.

Next Iwill say a little about the environment that Bronislaw Malinowski came from-the city

of Cracow.

We are indeed in a different epoch when we speak about Cracow in the early decades of this

century. Cracow, an ancient capital of Poland, was a major cultural center of the old com-

monwealth. From 1815 to 1846 a free city, it preserved some of the political tradition of its

unique, local freedom. By 1860 it was a city of about 50,000. Next to an important and ancient

university, it had theaters, influential newspapers, and many coffee houses where there was

discussion, conversation, and politics as people sipped coffee and read newspapers. By the first

decade of this century it was a city of 200,000 or more. A typical Central European intellectual

center, although an impoverished one, Cracow was also a center of political life. The Polish

conservative party exercised a powerful influence in Austro-Hungary, and the powerful dem-

ocratic socialist party, with its adult education, health insurance system, and trade unions had

the overwhelming support of the working class and an energetic and intelligent leadership. In

addition, Cracow was at that time a Polish center of literary and artistic life. This was the city

of Malinowski’s childhood and youth: a modern and lively cultural center in a medieval frame.

Bronislaw Malinowski was born into the family of a university professor, Lucian Malinowski,

who died early. Lucian Malinowski was quite well known as a professor of linguistics, one of

several prominent linguists at the university at this time. Baudouin de Courtenay, one of the

fathers of modern linguistics, was the most outstanding.

Bronislaw, called throughout his life by his family and friends by the diminutive Bronio, went

to the Sobieski Gymnazium as a sickly, weak boy. Gymnazium life was demanding and diffi-

cult. The entire curriculum consisted of required courses, no electives. At the time when I at-

tended, if you failed in only two subjects you had to repeat not a term but the entire year; if you

repeated and failed again, you were out.

The faculty and administration were quite severe. School infractions were punished by car-

cer-hours of additional attendance; one had to copy an ancient text. Sobieski was a classical

gymnazium with Greek and Latin. However, Malinowski attended classes only for a few

months every year. It seems to me that it was only in the fourth class that he was there for a full

year. He suffered from poor eyesight all his life, and he was not very healthy. So the coaching

was done by his father, and that may partially explain his interest in linguistics, or rather his

knowledge of linguistics. After his father’s death he was tutored by Kazimierz Nitsch, also a

renowned linguist.

When Malinowski spoke to me about these early years, the person he mentioned frequently

was his mother, for whom he had a profound sentiment. He told me how his mother read the

books to him when he couldn’t read very well because of his poor eyesight, and he said that

some of his happiest days were in Cetynya in Montenegro. At that time, Montenegro was a

romantic kingdom, famous among the stamp collectors, and ruled by King Nikita. He was there

with his mother recovering from illness, and his mother read to him for hours. Equally happy

were the long vacations on the Canary Islands in 1907. His father died when he was only 14,

in 1898.

Now it is time to comment on his education, his early interests, and last but not least, his

friends of those young student years. But before that, let us ask still another question. How did

it happen that in this northern city-so far from the tropics, distant in history, interest, and space

from what was falsely considered at that time “a romance of the colonies,” that here, in a rather

comments and reflections 557

medieval urban setting, you find a young man who dedicated his life primarily to the anthro-

pology of the Pacific. (There was no chair of ethnology at that time at the University of Cracow.)

In the introduction to one of his essays dedicated to James G. Frazer, Malinowski says that

he was particularly influenced by Frazer's The Golden Bough. I don't think that was the only

influence. At this time, there was a passionate interest-more than an interest-a fascination

with the unknown, with undiscovered lands and their inhabitants.We lived in entirely different

times then. When we were 11 or 12 years old, we got our school atlases for our first geography

classes. (Iremember well my Atlas Kozenna-the most valued book next to Robinson Crusoe.)

On some maps we found white spots. This was the mark to indicate that the region was still

unknown, untraveled. That was what we were looking for. It made us think that perhaps there

was a place where we would be the first visitors. It fascinated us tremendously when we studied

those maps in the evenings with a glass of tea on a dining table. In the 18th century Alexander

Humboldt described how he was attracted by the unknown, the undiscovered world. Joseph

Conrad also wrote about it. When we studied geography and anthropology at the university,

we were referred to such publications (today almost entirely forgotten) as Clobus or Peters Re-

ports-if I remember the name correctly-where you had the reports of recent discoveries.

There we read about Colonel Przewalski (of Equus Przewalskifame) reporting from Central Asia

about the lakes of Lop Nor and Kuku Nor. We read about Sven Hedin, a young Swedish geog-

rapher and explorer. And I think Malinowski, like many others, was fascinated by the romance

of the unknown, not solely by anthropology itself.

At this time, Poles were making a contribution to the ethnology of Siberia and East Asia. Here

I should mention Waclaw Sieroszewski, who wrote a classic study on the Yakuts, and the lin-

guist and ethnographer of the Ainu of northeast Asia, Bronislaw Pilsudski (brother of Joseph

Pilsudski, later president of Poland). These two were socialists of the insurrectionist tradition,

exiled to Siberia, who carried out fieldwork while in political exile. Talko Hryncewicz, a phys-

ical anthropologist, was a prominent scholar in his field and, finally, there was Jan Czeka-

nowski, whose Forschungen in Nil-Congo Zwischengebiet-a study of the African territories

between the Nile and the Congo-was considered a major contribution in my time. I do not

know whether Malinowski was familiar with these writings, although he knew Czekanowski,

since he mentions him in his letters. He never mentioned them in conversation.

In his entire bibliography, I found only a single and early review on Slavic ethnography, of

L. Niederle's "La Race Slave" (Man, 1911) and he wrote an introduction to a major volume

(which I could not locate). He had no interest in Slavic or Polish ethnography or folklore.

Now let us talk about the university environment, and then go to his peer group, and then

return to his family. Malinowski finished his gymnazium with highest honors. He passed with

brilliance the "Matura," a difficult comprehensive exam at the end of the gymnazium.

When he entered the University of Cracow, he did not study any social sciences, nor was

there a department of social sciences at that time. Social sciences, economics, statistics, and

political theory formed a part of juridical study. We are again at the turn of the century, and

there is no social anthropology in continental Europe. What we today call social anthropology

could be found in the faculty of law (there it was called comparative law), perhaps in philos-

ophy (or those few chairs of sociology), or in geography.

Still the well-known and prominent cultural anthropologist Leonhard Adam, author of the

pioneering book on primitive art was at that time-if I remember correctly-a practicing law-

yer. Adam was the editor of a journal on comparative law and published studies in juridical

anthropology and also in American journals. But Malinowski, it seems, did not dwell on this

tradition. The university, like many medieval universities, was at that time divided into four

faculties: philosophy, law, theology and medicine. Physical anthropology belonged in the

medical faculty.

Malinowski was primarily interested in science and philosophy. He studied physics, math-

ematics, natural science, and philosophy. There was some psychology in philosophy-he stud-

558 american ethnologist

ied this with Wladyslaw Heinrich, a broadminded and quite independent scholar. With time,

Malinowski developed a strong interest in and taste for philosophy. Bronislaw found an intel-

ligent and witty mentor, who fitted well into this unique intellectual milieu of Cracow. Father

Stefan Pawlicki, a Roman Catholic priest and professor of philosophy, was-as 1 see it-a kind

of a refugee from theology. Pawlicki-a monk and priest-came from the Warsaw University.

His interest oscillated between theology and positivism, ancient philosophy and rationalism. A

member of the Papal Academy of Rome, he was described by one of Malinowski‘s friends and

a prominent writer (Boy Zelenski) as “a monk who was an admirer of Renan and Anatole

France. A positivist philosopher, epicurean, gourmet and charming buffoon.” Pawlicki was a

brilliant scholar-original, openminded, friendly, and pleasant. This secular, irregular, glutton-

ous, ebullient and talented monk (not Freud or Marx) was Malinowski’s admired philosopher

and teacher.

Malinowski was not only his student, he was also his friend. At the Polish Institute we have

copies of letters written by Malinowski to Pawlicki. They are lettersof friends. I have the impres-

sion that Pawli.cki was a kind of substitute father, since Malinowski lost his father very early.

He wrote Pawlicki very cordial letters when he was in England, and also I think when he was

doing some of his fieldwork.

In his early years, Malinowski does not show any interest in anthropology. His interest is in

philosophy. We also have his long handwritten manuscript on Schopenhauer and Nietzche.

He was interested particularly in the history of philosophy, which he studied very carefully,

and in “hard” sciences. Even in his memoirs, when he mentions his colleagues, they are often

from the sciences.

On a distant Pacific island, in the midst of his ethnological field work, he returns in his dreams

to sciences, to his laboratory and his colleagues. He writes in his Diary (January 21, 1915):

“Strange dreams. In one I dreamed that I was experiencing the chemical discoveries made by

Dr. Felbaum and Gumplowicz, and that I was reading their works or rather studying them from

a book. I was in the corner of a laboratory. A table, instruments, and Dr. Felbaum sitting there.

He made six inventions . . . ” Science, his major, intense interest like early love came back in

his dreams. Perhaps he was still undecided: anthropology or perhaps a return to chemistry or

physics. He was a very young man at this time. He could have made a turn.

His doctoral dissertation, “On Principles of Economy of Thinking,” submitted in 1908, is

indeed quite short. It is a manuscript written in longhand of about 72 pages and 21 footnotes.

In a recent Polish edition of Malinowski’s collected works (1 980) it covers 31 printed pages. It

is not his handwriting (so it seems to me) but perhaps his mother’s. It is short, indeed very short

in terms of our current academic standards. The dissertation deals primarily with the theories

of Mach and Avenarius, and its major theme is the function of science. Here one finds already

the beginnings of functionalism and his theory of function. Malinowski poses the question:

What i s the function of science?The answer is as short as it is seminal: economy of thinking.

We become more and more economic, while perfectingour thinking. The economy of thinking

is tantamount-he argue-to a minimum expenditure of work to achieve a result or maximum

result given the same means. In his reasoning Malinowski follows closely (although in a critical

way) theories of Mach and Avenarius.

At this time, he had little interest in sociology. His theory of functionalism originates with

philosophy, not with Spencer or Durkheim. It was a brilliant dissertation. Malinowski-at this

time 22 years old-earned a special distinction, the Sub Auspiciis Imperatoris, a special rec-

ognition of the Emperor Francis Joseph (Cracow at that time was under Austrian rule), a dis-

tinction very seldom awarded. He received a golden ring from the emperor, which was later

lost or stolen.

An early interest in cultural anthropology by the future author of Coral Gardens appears in

his studies of primitive religion and belief. Perhaps Pawlicki’s interest in theology and later in

positivism is also reflected here.

comments and reflections 559

In 1911 he writes a number of articles on James Frazer and on totemism for the Polish eth-

nographic review, Lud, and in 1915 his major Polish volume on primitive beliefs and society

(Primitive Beliefs and Forms of Social Order. . . The Origin of Religion and Totemism) was

published by the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Critical as he was, years later he told me he did not like this study at all. Between 1910 and

1914, Malinowski published a number of studies and book reviews in Polish and English,

largely on Australian religion or social systems, some of a more general nature. However, a

major step was his lecture at the Polish Academy of Sciences in 1912 entitled “Tribal Male

Association of the Australian Aborigines” (published in the Bulletin of the Academy in 1912).

A lecture in the Academy was tantamount to an acceptance into the company of scholars, rec-

ognition of his work and knowledge. It was a gradus ad Parnassum. (Papers were submitted

first for acceptance by the members of the Academy’s section. Following presentation and ac-

ceptance, the digest appeared in the Bulletin and the full text was frequently published by the

Academy.)

Malinowski‘s education, however, was not limited to his mentors and teachers at the Uni-

versity of Cracow. He traveled extensively in Europe, studied in Germany, later of course in

England, and in 1908-09 after his Ph.D. he studied in Leipzig. We learn from the detailed work

on Malinowski of Prof. K. Symmons-Symonolewicz that, in addition to his study of chemistry,

he also attended classes of the psychologistWilhelm Wundt and an early social anthropologist

(probably at that time called an economic historian) Karl Bucher. Today almost forgotten, Karl

Bucher, admired by Friedrich Engels, wrote at that time his famous Rhytmus und Arbeit

(Rhythm and Work). The original function of music-particularly rhythm, wrote Bucher-was

the organization of collective effort in agricultural work. There is thus some foreshadowing of

the functional approach in Karl Bucher’s sociology of music.

At this time, Malinowski’s study abroad was a part of the tradition of a sound education.

Incidentally, the concept of “postgraduate studies” was absent. After the gymnazium and the

academic exam (matura) a student could matriculate. The university study consisted of a pat-

tern of courses, of many electives culminating in a doctoral dissertation and degree. The tra-

dition of traveling abroad in search of academic knowledge was an ancient one in Poland. it

went back to the 14th, perhaps even the 13th century, and extended also to crafts. In my youth,

apprentices in the printing trade in Cracow still traveled abroad, especially to Germany. In this

study abroad a student did not collect any degrees. Often he already had one, and in a true

scholarly tradition, one searches for knowledge not for honors-one degree i s enough. Mali-

nowski was enrolled at Leipzig.

In 1910 he left for England and began study under his new mentor, C. G. Seligman, but re-

turned in 1913 to read at the Academy a paper on “Relations Between Primitive Religion and

Social Structure: A Theory of Totemism.” Now, his “other”-English-life story begins.

But the picture would not be complete without at least mentioning his peer group. Stanislaw

Witkiewicz (Witkacy) the well-known surrealist playwright; Leon Chwistek, mathematician,

logician, art theoretician, and modernistic painter; and the poet Tadeusz Szymberski were

close, brotherly friends, very close indeed.

Leon Chwistek was a kind of Renaissance man, a mathematician pioneering in new ways

and in logic, experimenting in modernistic painting; Chwistek was my mathematics teacher for

all the eight years of gymnazium. I learned about Malinowski from him. He told us that the

pearl pin on his tie was given to him by “my friend Bronislaw Malinowski-he got it from the

native pearl fishermen.” Chwistek was later a professor of the University of Lwow and Moscow.

All three were talented and creative men. All thre-r their painting+appeared on Polish

stamps, Malinowski also on the stamps of New Zealand or Australia. But their friendship was

marred later by strong discord-with Chwistek even by silent animosity. Malinowski had a

deep sentiment for Szymberski, calling him by the diminutive “Tadzio.” He remarked several

times that “Szymberski was the most talented, the most promising of all of us.” He is now a

560 american ethnologist

long-forgotten poet of “Young Poland,” a group that was at the time what we would today call

“trendy.” But he never gained the fame the others did.

There were others whom Malinowski liked and appreciated. Boy Zelenski, a writer, a kind

of Polish Voltaire who was popular among liberals, opposed the power and influence of the

Church. Zygmunt Zulawski, later a prominent labor leader and democratic socialist, and a dep-

uty in the Polish Diet, was one of this promising group of young men as well as his brother,

Jerzy Zulawski, an early science-fiction writer. This group of three or four friends selected lec-

tures together as well as the subject matter to study. They went mountain climbing, meeting in

Zakopane in the Tatra Mountains, in the villa of Chwistek‘s father or in Zulawski’s.

Malinowski also mentioned once that Jan Kasprowicz, a well-known poet, had invited him

to tea. As Malinowski recounted it, the poet had said: “Come over for tea. You will meet a quite

interesting man. He is a Russian revolutionary. His name is Lenin.” Lenin lived in Poronin, a

village next to Zakopane. Malinowski replied: “Listen, they tell the same stories, they always

lecture you about Karl Marx, they are a dull crowd.” But Kasprowicz said: “Come over. He is

an intelligent man, and we have to be polite.” And so he went over. He had a long conversation

with Lenin and found him sympathetic and pleasant. In personal relations with those unrelated

to his political religion, Lenin‘s authoritarian, despotic, and dogmatic qualities were not re-

vealed.

Let me correct some of my earlier statements. On the one hand, Malinowski did not refer to

Polish ethnologists in his early writings. Also, when we spoke about the past, he did not men-

tion them. Still, his early work appears in a Polish ethnographic review, Lud. Hence, he must

have known the editors, who were ethnologists. Furthermore, he presented his work at the Pol-

ish Academy in the same section where Bronislaw Pilsudski had presented his work in ethno-

linguistics, on the language of the Ainu. The sometime president of the Academy, Jan Rozwa-

dowski, a linguist, probably presided over Pilsudski’s and Malinowski’s meeting.

Malinowski knew Polish linguists very well-his father was among the group. So was Roz-

wadowski, for whom Malinowski felt warm friendship and appreciation. An extensive and per-

sonal correspondence testifies to it. Malinowski’s tutor was a prominent linguist, Kazimierz

Nitsch. Malinowski‘s original linguistic theories and work can probably be traced to this early

association.

However, he did not care much for a purely descriptive ethnography. At one time he made

critical comments about descriptive, patriotic ethnography, concerned, as he said, with em-

broidery and ornamentation, a study of embroideries on ladies’ panties.

The author of Freedom ,nd Civilization had a sentiment for Poland, but not a nationalistic

one. He loved his friends, appreciated scholarship, and was attached to the landscape. In fact,

during my last stay in London-I think it was in 1937 or 1938-he asked me to take care of

two things: to discuss with Rector Estreicher his lectures at the University of Cracow, and also

to take care of Szymberski, whr, was working at that time in Paris. No one remembered his

“Young Poland” poetry anymore, and Bronislaw thought he must be very lonely. In Cracow I

spoke to Rector Estreicher, at that time president of the Academy, and a professor who was

really interested in Malinowski and supported his work. He wrote some letters on this matter.

It was Estreicher who in 1914-1 915 took care of publication and proofreading of the book on

primitive religion when Malinowski was in the Trobriand Islands. I told Estreicher that Mali-

nowski wanted to come back to the university to give a few lectures, that he had told me in a

nostalgic way that he would like to walk through Planty, a garden that surrounds the old city

wall, and also to visit Wawel Castle, stopping at Dominican Square w h e r e a s he told me smil-

ing-in an old cukiernia (pastry shop), they had very good ice cream. Estreicher arranged

through the Academy for a salary increase for Szymberski, but despite his support, was unable

to arrange an invitation for Malinowski to visit the university. The Vice Minister for Public In-

struction was strongly opposed, and did not appreciate social anthropology as a discipline.

comments and reflections 561

This was rather strange and unusual. During his entire life in England and in Western Europe,

Malinowski remained in cordial and direct correspondence as well as friendly relations with

the academic community of the University of Cracow as well as with the Polish Academy of

Sciences. In 1922 he was offered a chair of ethnology at the ancient university, which he how-

ever refused to accept, indicating that his primary commitment was to continue to prepare for

publication his scholarly materials, especially his New Guinea fieldwork of 1914-1 8. In 1931

he was elected a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences, which he represented later at

scholarly meetings, among others at the centenary celebration of the University of London and

also at Harvard.

At this point, however, let us ask another question: How far did his formative years, his stud-

ies in Cracow, his peer groups, and a broader scholarly and cultural Community affect his per-

sonality, his work, and his outlook? Is it possible at all to identify this influence? It is of course

only a guess, an impression. Any quantitative attempt would indeed lead to pretentious non-

sense. No doubt his classic education and later his studies in science and philosophy formed

his way of thinking, his scientific logic. The original idea of function appears very early, already

in Malinowski’s dissertation. His aesthetic sentiment and literary tastes were shaped in those

early years by his close Polish friends: poets, painters, and literary critics. His linguistic interests

and concepts originated in the Cracow intellectual community.

As late as 10 November, 1922, he wrote to the Polish linguist Nitsch Kazimierzu: “Dear

Casimir [in fact, it is both more cordial and more formal at the same time, but not easy to trans-

late: ”Beloved Mister Casimir” (Kochany Panie Kazimierzu)] I wrote during the last few weeks

a linguistic article, which summarizes our discussion. I shall send you a reprint as soon as it is

printed.” (Perhaps this was “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages” as Dr. G. Gra-

zyna-Klyszcz suggests.) Malinowski’s science and philosophy were nurtured in his young years

in Poland, his anthropology primarily in England.

His taste for and interest in cultural anthropology was prompted, and later educated (to fol-

low his own statement in the introduction to his “Myth in Primitive Psychology”) by such writ-

ers as James Frazer and other British scholars. It did not come from Polish ethnographers, al-

though this branch of scholarship was already well developed in Poland in his youth. His an-

thropology was primarily English, of course, but such a statement is neither complete nor

sufficient.

The personality of such a scholar is a result of the fusion of several cultures and traditions.

The two major sources of his early scholarship can be found in the Polish and British academic

and intellectual environment. The dominant impact on his professional education was British,

and it was not Frazer alone. Malinowski wrote to the president of the Polish Academy, JanM.

Rozwadowski(7 January, 1922): ”I wrote also to my friend, teacher and pour ainsi dire impre-

sario, Seligman [C. G. Seligman], professor of Ethnology in London, most decent person under

the sun to me-as long as I have known him-he is and was an older brother.” Rozwadowski

had again extended an invitation offering him a chair in anthropology at the University of Cra-

cow. Malinowski writes, “Seligman asks me not to make any plans without consulting him prior

to his return to London. Now,” continues Malinowski, “he makes a promenade between Sudan

and Uganda.” Throughout his correspondence one finds his strong identification with English

scholarship and this fuses with his younger years and education. But can we reduce the form-

ative influences only to those two? To relax, he enjoyed reading Goldoni’s comedies in the

original, Italian text (he had those beautiful, illustrated volumes handy on his shelf), or listened

to French music or Mexican folk songs.

During the war the author of Freedom and Civilization became engaged with postwar plans,

the future. During the interwar period, he strongly opposed any form of totalitarianism. In the

Italian fascist press he had an honorable place next to Freud, Hirschfeld, and others as a cor-

ruptor of youth. I remember there was an article in 1938 in the Italian newspaper Corrieredella

Sera by ProfessorCipriano Crispi entitled “I1Problema di Semitismo” in which Malinowski was

562 american ethnologist

very strongly attacked as a Jewish corruptor of society. The same charge, if I recall, appeared

in I / Popolo d‘ltalia, a fascist newspaper (on the right side in italics you could find short edito-

rials by Mussolini).

On the Jewish question, I perhaps should add a little more, because there is a good deal of

misunderstandingon this score. When I met him for the first time, he invited me to his office in

Aldwych and we had a short conversation. We had dinner in the Commons, where I met var-

ious luminaries of the London School such as Harold Laski and Carr Saunders, names I knew

only from books. Then he said, “Tomorrow you will come for lunch.” I went and he prepared

lunch, opening a tin of peas and other dishes. He said in a somewhat apologetic way (it was a

time when professors had servants and private secretaries) that he was at that moment alone

(his first wife had died), since he had sent his secretary and servant to Vienna. This was after

the occupation of Vienna by the Nazis, or rather when sections of the Austrian population

turned to fascism in the worst way. “I sent them,” he said “to help my Jewishfriends. They still

respect an English professor, and I’m doing my best to help them.” His close friends in Vienna

were Paul and Hedy Kuhner. Kuhner pioneered in the manufactureof vegetable oil. Margarine

in Austria was known as Kunerol, Kuhners Oil. He had spent some time with the Kuhners in

the Pacific Islands when the Kuhners were interned. He also had sympathy for JewishGerman

refugees, and his personal physician was a young Tyrolean Jewishdoctor. I was personally the

recipient of his friendly attitude. When, because of my religion, origin, and political views, it

was not possible for Rector Estreicher to suggest my name at the university, Malinowski was

instrumental in my appointment to the University of London as occasional lecturer in cultural

anthropology; a stipend of f50 per term was attached to my paid entitlement as his research

assistant. Malinowski also wrote an introduction to my book on nomadism and recommended

it to the Academy for publication. He appointed me on the basis of this book, and one other,

called Proletariat and Culture, based on fieldwork in the coal mines and factories. I remember

it was still in proofs when I came to London. He would stay with me day by day and I would

read him sections of the book, and he would comment.

Ethnic, racial prejudice? His Diary, published in 1967, was quoted by some anthropologists

as evidence of his prejudice. His use of the term “nigger”-although in a polonized version

(he wrote those pages in Polishkas Professor Symmons-Symonolewicz correctly indicates,

does not have this connotation (see the Postscript below).

Amicus Plato, magis arnica veritas. Let me still add that in one of his letters, one may notice

at times what we may call a minor ambivalence, but with a definite bend. He wrote in a friendly

and informal letter to the presidentof the Polish Academy, Rozwadowski (1 2 December, 1923),

that ”Vienna now is full of Jews-but as far as myself, I can now only stand the company of

Jews-and among them I have my best friends-and this,” he continues, “leads me to my first

business.” Here he recommends Dennis Cohen, from the Palestinian civil service, who in-

tended to visit Poland in connection with the emigration of the Jews. He asks the president of

the Academy to introduce him to “decent Poles, not to the extreme nationalists. Could you

perhaps talk with him, introduce him also to some Moguls and generally help him?” Inciden-

tally, Malinowski liked to use in Polish some of the terms that were used in a daily parlance of

his time, not too respectful, sometimes witty, but with no malice.

May I add that his Polish was direct, witty with some Cracow student slang. Even in his formal

letters, he will, in a direct and cordial way, break into some expressions that could be called

nasty. In conversation he expressed strong, warm friendship, but sometimes also strong abra-

sive, critical views about those he did not approve of or like. I know this from my own expe-

rience and conversation, not from letters. He might have changed his views in his lifetim+

one way or another as he himself indicated. But as I knew him in the late 1930s and during the

war years, he was a courageous opponent of fascism, racism, and any form of totalitarianism.

He helped and assisted victims of antisemitism; his convictions were not reduced to words

only.

comments and reflections 563

Malinowski felt that scholars, and he personally, should contribute to building a more hu-

mane world. Extreme political nationalism and racism he believed were a "major curse." As

you know from his book freedom and Civilization, he made a distinction between nation-state

and nation-culture, between tribal-state and tribal-culture. He thought it important to empha-

size the relevance of nation-culture, but he suggested that the political power connected with

the nation should be separated from the cultural. Perhaps he didn't realize that these were ideas

not very far from those of Otto Bauer and Karl Renner, the Austrian democratic socialists, who

suggested a similar solution for Austro-Hungary before World War I. Bauer and Renner ad-

vanced plans for full cultural autonomy for all ethnic groups (nationalities), cultural self-gov-

ernment separated from political territorial power.

We were working together on a book on nationality in this vein. In his theory of nationality

he emphasized the objective empirical elements, those you can observe. He was critical of any

study of subjective concepts of nationality, of national consciousness. His emphasis was always

on phenomena, facts that could be observed. However, in political behavior, self-identification

is relevant, it may and it does determine behavior. After 191 8, the principle of "subjective"

nationality, expressed by self-identification (for example, in plebiscites and referendums),had

in extreme cases negative social effects. It contributed to the emotional manipulation of na-

tionalistic issues, and eventually led in Germany to racist self-identification. The principle,

however, has to be distinguished from its extremist use. He considered the nationality issue as

paramount in postwar planning. Institutions were needed, he thought, which would secure

cultural freedom for various nationalities and also prevent the use of political power and vio-

lence for nationalistic policies of conquest and oppression.

Czechoslovakia,Greece, Yugoslavia, and Poland formed at that time the Central and Eastern

European Planning Board. Its purpose was planning for a democratic reconstruction of Central

and Eastern Europe in the spirit of social justice and confederation. A regional confederation

as a part of a European Community was already outlined. The Planning Board was an early

initiative toward a future European Community, and I was elected secretary general of the Plan-

ning Board, in charge of general planning. Malinowski was interested in our work, and we met

once together with Jaromir Necas, Czechoslovakian Minister of Reconstruction, a democratic

socialist and one of the most constructive postwar planners among the allies.

Some of his views in freedom and Civilization reflect our discussions. War dominated his

interest and conscience. He wanted to make a constructive contribution toward solutions that

would protect mankind against the repetition of the brutal follies of our generation.

In those war years, he considered it his foremost task and duty to devote his time to construc-

tion of a better, more humane world. His freedom and Civilization was a consequence of this

world outlook and desire to contribute in a positive way to reconstruction of a brutalized man-

kind.

"I am a world citizen by now," he once said to me in a conversation. Was he a British or a

Polish scholar-a question Raymond Firth once discussed with me. Professor Firth (it seems to

me) felt that he was in fact a British anthropologist. But-one can be both. We have created a

social myth of a single ethnic identification.

In 1923, Malinowski seems to be quite aware of his own binationality. In 1923 (a letter of 7

July), he writes to the president of the Polish Academy about representing the latter at an an-

niversary of the University of Naples: "I could of course represent the University of London.

But 1 prefer to represent as a Pole. I could represent as a doctor of University of Cracow or as a

Polish "savant," the Jagiellonian University or the Polish Academy."

His idea of world citizenship reconciled his emotional or rational conflicts. "We stress so

much cultural differences," he once said to me, "that we forget the unity of mankind."

Malinowski felt sympathy for England and for the United States, but he also had strong Polish

sentiments of a specific kind. He liked the landscape, he liked his friends, he liked part of the

tradition. When he went to Mexico, I asked him not to climb mountains and run around so

564 american ethnologist

much in case he ran into health problems. He said, “You know, it’s so pleasant in these small

towns. There is mud, dirt roads, just like in the old country. It’s not all asphalt. I can walk on

the dirt roads in the towns, among crumbling houses. It’s nice to see that again.”

As late as in 1923 (letterof 12 December), he writes to the linguist Jan Rozwadowski, “Please

answer this letter and write to me something which would give me a chance to breathe again

the air and mood of Cracow. I am monstrously depressed-mostly health. How do you feel?’

And agai-prior to this (7 January, 1922)-“Please write to me a long letter. At times there are

moments that I am very homesick, lonesome for the (old) country, but I almost fear to return.”

He already sensed that he had changed and so had his native town. When he was still on the

Pacific Islands, he returned continuously even in his dreams to his Polish past, his mother,

friends, places he knew, and he recorded this carefully in his Diary. His sentimentstoward his

old country and old friends were human, humane but not political. Extreme political nation-

alism was an ideology he rejected.

He was very critical of his own work as well as of himself. His criticism, sharp and intelligent,

extended to the academicians as well as to nations and societies he was a part of. Once, when

we discussed the general, cultural contribution of Poland, he said curtly, “Only music, good

music-what you find among the people.” He was similarly critical of American Poles. I was

associated with the Polish-American labor movement, vigorous at that time. I told him about

those intelligent, dedicated, and progressive people. “You may not know them,” I commented.

He thought a moment and said curtly: “I know them. One of my ancestors was cut in half with

a saw in Rabatsia.” [Rabatsia of 1846 was a peasant rebellion in southern Poland, tolerated if

not instigated by the Austrian administration against the nobility.] Family l o r w r truth-I do

not know.

freedom and Civilization was his last book. We often discussed his ideas, and he sent me

some chapters for comments. He expressed his views clearly; an opponent of total government,

he did not spare Stalinism. Malinowski’s death came suddenly. A few days after he died, Valetta

(his wife) told me that this manuscript (previously accepted by a well-known publishing house)

had been rejected. I told her to keep the advance. While walking through Central Park to my

office I met Marian Kister, the publisher of Roy, at that time a successful publishing house from

Warsaw transferred to New York. I asked if he would take a book of Malinowski’s, and he said

“lmmediately.” And that is how freedom and Civilization came to be published first by Roy.

Let me add a few comments on Malinowski’s personality and on his methodology. Now, we

are back a decade prior to World War II. Modest in his personal expenses, he used to buy those

five-guinea tweed suits at Burton’s in London. He spent little money on himself, but was gen-

erous to others, and did not forget the friends of his young years. Malinowski enjoyed eating in

inexpensive places. Sometimes he indulged himself in a treat, and once invited me to join him

for coffee at a place in Rockefeller Center next to the ice skating rink. It was the closest thing

to an old-time cafe; the coffee was quite expensive-25 cents, five times as much as at Horn

and Hardart. (Subway fare was at that time a nickel, so in those terms it was a horrendous five-

dollar cup of coffee.)

He liked inexpensive clean restaurants, like Horn and Hardart or Childs, and we met there

when he came from New Haven. In his home in New Haven, as well as here, we discussed

many topicstheories, war and its tragedies, and postwar plans for reconstruction. But there

were also moments of leisure when we sat in the corner of this 42nd Street restaurant and ob-

served people-trying to identify their background from the dishes and ways they ate. Many of

the New York Public Library readers congregatedhere, especially those from the Slavonic read-

ing room. The rye-bread eaters at that time were East European ethnics. They, like the Russians,

preferred tea from a glass rather than a cup. Here were those who never got used to white toast

or peanut butter.

We used to meet at his seminar in the New School. Sometimes, when he was casually de-

veloping his theory of culture, students interrupted, at times abrasively. He did not like it at all.

comments and reflections 565

We continued our conversations while walking toward the old Penn station, from where he

took a coach to New Haven.

Professor Konstanty Symmons-Symonolewicz, in his remarkable study of the author of Free-

dom and Civilization (see Postscript), gathered a variety of learned, friendly and unfriendly

opinions about Malinowski's personality. In an attempt to be unbiased or objective, Symmons-

Symonolewicz has leaned somewhat toward the critical, may I say negative. He wrote, "One

of his characteristics many of his critics disliked was his megalomania, combined with lack of

responsibility and seriousness, and thedisplay of a certain actor's skill in his writings, addresses,

lectures." George P. Murdock and Ashley Montague stressed, however, his warmth, friendli-

ness, and personal modesty. His vanity hid his warm, sensitive personality, suggested George

Murdock, a generous comment since Malinowski was quite critical of Murdock's cross-cultural

approach.

It is not my purpose, though, to present to you this variety of views. I shall relate here only

my own experience and impressions. Perhaps because of it, a personal note is justified. He was

friendly and helpful to a young stranger, willing to assist and generously give his time. This may

also bias my evaluation. I found him a warm and friendly person who remembered his old

friends and was always ready to assist. He was a devoted and concerned father of his three

talented and handsome daughters, Wanda, Josefa and Helena. In conversation, he was sharp

in his criticism. But his strong criticism was expressed in personal conversation, not in print.

Yes, he was critical of Boas, Margaret Mead, and Ruth Benedict in various degrees. But in writ-

ing, in his published material, he was courteous and restrained. Remember too, that he was

quite critical of his own work.

Malinowski was very well read, but never showed this. Until recent years, I did not know

about his studies of Mach, Avenarius, Nietzsche, and so many others. He never mentioned or

displayed his erudition.

He concentrated above all on writing his own books, limiting his reading to what he consid-

ered the most relevant works. Florian Znaniecki, at that time at the University of Illinois, was a

major social scientist of our times. When I asked whether he had read any of his work, he said

No, but he added: "Tomorrow we shall go for a walk, you will tell me whatever you know

about Znaniecki's work."

Megalomania?In his books, he repeats continuously that he is not the first, that others had

similar theories.

Hypochondriac, as some argue?He was quite often sick, and losing his eyesight. Toward the

end of his years he told me that he had lost sight in one eye. He knew this was not helpful with

many professional colleagues, and asked me not to tell anybody about it.

His political views? We have discussed these extensively already. But his political outlook

could have changed too. His theories were shaped by facts and observation. Observation was

his habit and could affect his world outlook. It seems to me that in 1940 he was far more po-

litically alert than in 1914. During the war period his views approached moderate, democratic

socialism. He said once that he had revised and changed his views after he visited the workers'

colony, public housing built by the social democratic municipality of Vienna. He was im-

pressed by the contribution they had made to the welfare of the working class in this-at that

time-impoverished city and country. There was also an emphasis on aesthetics in Viennese

workers' quarters, absent in our public housing. What the Austrian Labor administration con-

tributed in municipal government was rather amazing at that time.

In his young years, in his Diary he may appear a self-centered but searching and honest

young man. In his mature years his liberal viewsare clearly expressed. He responds openly and

in an uncompromising way to the European counterculture and countercivilization.

Malinowski died on May 16, 1942. He had a heart attack following a meeting at the Polish

Institute when he was elected its first president. To be honest, he was quite hesitant about ac-

cepting the presidency. It was suggested that the historian Oskar Halecki, a professor from For-

566 american ethnologist

dham, or the Columbia papyrologist Rafael Taubenschlag be nominated. However, leading

persons in London thought that Malinowski would be far better suited to chair the continuation

of the Polish Academy of Sciences if people cared to elect him. I conveyed this information to

him and tried to convince him. At this time, when Polish scholars in Cracow had been sent to

the concentration camp and executed in Lwow, establishment of the Institute was an act of

struggle, survival, and protest. Valetta said to me later that deciding this matter was psycholog-

ically stressful for him. It was however a moral imperative to which he was sensitive.

Finally he accepted, but we had met many times to discuss it. When I got the telegram from

Valetta and a call from Maurice Davie, chairman of sociology at Yale, I went immediately to

Yale to take care of his manuscripts and to do whatever was necessary. After we cleaned up his

room, I thought perhaps there was something I had forgotten. I remembered asking him once

if he had ever written his memoirs. That was one time when he was very brisk with me, even

somewhat unpleasant. He said, “You shouldn‘t ask that question. I never wrote them.” I

thought perhaps I should not have asked. It was a personal matter. Still, I thought perhaps he

had written them. just as we were leaving I thought again about the memoirs. I climbed the

shelving and touched the shelves on top. By accident I found three or four books, bound in

black, I think. I opened them. Here were the memoirs, the ones he had said did not exist. I

opened at the middle. The paragraphs I read were very personal. I glanced at a few pages and

thought that it was up to the family to decide what they wanted to do. So I gave them to Valetta.

Valetta (Swan Malinowska, his second wife) was a talented, self-taught artist-her paintings

were exhibited in the National Museum in Mexico. Intelligent and openminded, Valetta was

devoted to her husband and his work. She had a keen, self-taught understanding of anthropol-

ogy, and was also a good editor. It was Valetta who completed-through her editorial work-

the volume on Scientific Theory of Culture. She was also responsiblefor publishing his memoirs

and for the choice of texts.

On leaving Yale, I went home and recorded in my notebook the major issues we had recently

discussed together, especially his advice and comments. That was on May 19th. On 7 May, we

were still working together on the book on nationality. This experience was indeed the best

education in social anthropology I ever received. Malinowski believed that the problem of na-

tionality/ethnicity was one of the key issues for world peace, and that nationalism in its totali-

tarian political expression was a dangerous ideology. We worked out an outline that I still have.

One of my tasks was to check and compile the bibliography; at this time, the New York Public

Library was still open late at night. I gathered extensive notes on works from the middle of the

19th century to our time, but this project did not advance beyond many discussions, a draft of

a chapter, and our initial outline. He wanted to make a strong distinction between the nation

as a culture, which was essential and creative, and the nation-state as an armed power. After

discussing this issue he said, “Now we have to discuss the different types of war”-and here

he made a rough inventory-“(I) social, (2) ideological, (3)political, (4) revolutionary, and (5)

national.” This was quite typical of him. He would just list his ideas in a random way. He would

jot down all the ideas he had, make a rapid list. Then he would follow it up and analyze, or-

ganize.

Let me read to you the notes I made on 19 May, 1942, concerning his comments on methods:

1. Present the problem immediately at the beginning in a very definite and broad way. (This,

I should say, is different from Pascal who said in PensCe that the first chapter i s always written

at the end.) State the problem immediately; it will give you the guideline. While you work,

change continuously. Don’t be afraid to change and improve, perfectionner. (He often used

terms in different languages during the discussions, and knew many languages well. He was

quite critical when you made mistakes.)

2. Now the logic: Examples, yes; analogy, metaphor, never. Metaphor is very dangerous,

analogy a risky business. It was almost Seneca’s brevis iter per exempla. He acquired a vigorous

comments and reflections 567

logic in his young years. (I must say that I had reservations about his views on analogy later.

Cautious, reserved analogy is in fact nothing else but an effort at Comparison.)

3. It is essential to be careful, not to follow or advance easy or sensational theories or findings.

(He was critical of Margaret Mead for following impressive things.) Be very careful of anything

that has a smell of a sensational discovery because it might not be true In research don’t take

the easy way. (That he said in Polish-Latwizna-meaning that you take the easy way because

it‘s natural, palatable, impressive.)

4. Study phenomena from facts, behavior, never from ”consciousness“ or “introspection.”

In your definitions return always to the objective processes of life.

5. First read the most intelligent books on a subject matter, later the others. Don’t read the

Chinese or the Jews (he said jokingly). They have said everything. Once you have read them

you are too discouraged to do anything yourself. Quote your sources in your introduction and

then go on with your own ideas. (Today, we quote heavily, but English scholarly practice at

this time was to put your sources in the introduction and then go on with your own ideas. He

just followed this method.)

6 . Write an inventory of your ideas. As you proceed, you will come across ideas, data that

you may later forget. Do not try to organize the ideas and data all the time. Just jot them down

in rough form when you think of them. Then, while you work, return to them and incorporate

them if they are valid and relevant.

Let us make an additional comment. Malinowski valued criticism highly. “Welcome always

those willing to read and criticize your manuscripts or work-this does not mean that you

should accept their criticism, but listen always,” he said in one of our conversations.

Valetta organized the text of The Scientific Theory of Culture after his death. You may find it

9 little repetitive in certain places. He actually rewrote the text several times. He dictated sev-

eral versions. With each edited or improved text, he was not sure which one was better. And

indeed, at times the differences were small and it was hard to choose. He said that when he

was young he did not hesitate to accept an early version, but later he became a perfectionist. I

have been told that Flaubertwrote a paragraph a day. Malinowski rewrote his text many times.

As I have indicated, Malinowski did not come to anthropology straight from a department of

anthropology. In this he was not unique. Pasteur came from chemistry and not from a depart-

ment of medicine; the sociologist Pareto graduated from the famous Polytechnic Institute of

Turin and wrote a dissertation on “The Index Functions of Equilibrium in Solid Bodies.” The

great French sociologist, Gabriel Tarde, was a judge. We are at the turn of the century, when

the disciplines are still planted in general departments or “faculties.”

I should mention that Rector Estreicher, who took care of publishing his first book, died in

Saxenhausen concentration camp. After the German occupation, all the professors of the Uni-

versity of Cracow were invited one day to the university auditorium, where they were sur-

rounded by the Gestapo. Rector Estreicher was asked whether he would take over the presi-

dency of the province, like Quisling later. The commandant told the Rector he had half an hour

to decide (as I was later told by his son, Karol). Estreicher replied immediately: “The half hour

i s over, Colonel. I have decided no!” They were sent to concentration camps, where many of

them died. The faculty of the University of Lwow was largely executed. Witkacy, his close

friend whom you meet often in his memoirs, committed suicide at the moment the Germans

entered Warsaw. He couldn’t take it any more. This was a part of society closely related to

Malinowski, and he felt strongly the fate of these people.

Whatever the critics may argue-that Malinowski spent his life writing about small, un-

known, and little-appreciated human societies, not about the great civilizations that paved the

roads of history-he introduced to us, like a 19th-century gentleman, unknown people, called

at that time around the globe “savages,” and he said, “Here are our brothers. They have a

culture just as we do, at times a fascinatingone. Though their culture differs from our own, they

are the same as we are.” This was his message. His way was one perhaps first taken by Mon-

568 american ethnologist

taigne and later the philosophers of the Enlightenment-a road toward mankind-followed by

Malinowski with wit and gusto. A great scholar, excellent and witty in conversationand debate,

he was above all a good, humane, and generous man.

postscript

The intention of my Barnard College lecture was to present, in a rather informal way, my

personal recollections of Bronislaw Malinowski. What was not intended was a formal paper,

with all the academic paraphernalia. This casual presentation was taped and later typed and

edited by Shirley Lindenbaum and Pamela Smith. My lecture was casual, and I am thankful for

the excellent and hard work of both editors. Their version followed the spoken text.

However, after the lecture, I received from Poland a symposium dedicated to Bronislaw Mal-

inowski’s biography and work edited by Mariola Flis and Andrzej K. Paluch, Antropologia Spo-

leczna Bronislawa Malinowskiego (Social Anthropology of Bronislaw Malinowski; Warsaw:

Panstwowe Wydaw Naukowe, 1985). This excellent collection of studies and source material,

with interesting insights, but above all some new and heretofore unpublished data, necessitated

a revision of my text, and some additions.

Dr. Konstanty Symmons-Symonolewicz’ penetrating study of the personality of this promi-

nent anthropologist (“Osobowosc Tworcza Bronislawa Malinowskiego,” [The Creative Per-

sonality of Bronislaw Malinowski], pp. 63-92) called for some comments. My personal expe-

rience often differed from those of other students and scholars, whom Professor Symmons

quoted carefully and without bias.

I admit of course that I could be at times partial. But I wrote as I knew him and the social

milieu of his young years. I was rather shocked that some considered him arrogant, aggressive,

almost mean. I knew him always as a kind and friendly person, ready to help, direct and un-

pretentious, superb company and a wonderful conversationalist. Of course, perceptions may

differ. True, he had strong opinions and dislikes, but this goes for his critics too.

Incidentally, Professor Symmons-Symonolewicz‘ earlier studies, particularly his “Ethnogra-

pher and His Savages. An Intellectual History of Malinowski‘s Diary,” (Polish Review, 1982),

a careful review of evaluations and opinions by various scholars of Malinowski’s attitudes and

personality as a research scholar complement this last study. I found it very useful.

Furthermore, a collection of lettersedited by Dr. G. Kubica-Klyszcz (pp. 253-300) contained

some data unknown to me, which permitted me to expand on some topics. A careful research

of Malinowski‘s university study by Dr. Bronislaw Sredniawa, Institute of Physics, University of

Cracow (pp. 235-247), gives a revealing story of Malinowski’s extensive study and background

in the exact sciences. Bronislaw’s godfather, we learn from another study of Dr. Sredniawa’s,

was the prominent physicist August Witkowski. Malinowski’s precision in his work, even some

of his techniques (suggestedalso my late friend Professor Andrzej Waligorski and by Bronislaw

Sredniawa), may have come from physics and perhaps under the influence of Witkowski, who

befriended Malinowski’s family (Bronislaw Sredniawa, “An Anthropologist as a Young Physi-

cist: Bronislaw Malinowski’s Apprenticeship,” h i s 72:1981, p. 614). This new data also called

for revision of my original text and some additions.

I have reduced somewhat the original text, especially some of the anecdotal material. In

addition, I found in two cases a certain minor variance between what I remembered from our

conversations and what I found in letters. I remember distinctly that he told me once he spent

a few weeks or so in Montenegro. But Icould not find a trace of it in the published letters or in

his biography. I have tried to check my recollections against the published material.

In memoirs, recollections, even in direct observation, there i s always the problem of choice

of facts, perception of facts and memory. Whatever I have written is of course influenced that

way. And a good deal of what was said was a matter of my memory. I have checked as far as I

comments and reflections 569

could in an honest attempt to be truthful. This paper, however, corresponds in large measure

and general theme to what was said at Barnard.

Sources that were consulted for this paper have been quoted in this postscript. May I add an

early, thorough, and very valuable study on Malinowski by Eva Borowskaentitled Years of fol-

ish Youth of Bronislaw Malinowski, which covers his early life till his departure from Poland in

1910. This master's thesis of 1971, written in Polish, was submitted at the University of Cracow

and sponsored by Professor A. Waligorski. It could well qualify as a doctoral dissertation. I had

an opportunity to read this dissertation in manuscript form; it was never published.

A careful (although perhaps not yet fully complete) bibliography of Malinowski's publica-

tions as well as a bibliography of studies dedicated to his life and work, edited and gathered by

Professor Konstanty Symmons-Symonolewiczand Dr. G. Kubica-Klyszcz, have been published

in a recent symposium on Malinowski (1985, quoted above). This symposium contains also

several interesting and valuable studies (including Andrzej Flis's on "Philosophy in 19th-cen-

tury Cracow and Development of Malinowski's Scientific Views") related to our topic.

Karol Estreicher's volume Leon Chwistek Biografia Artysty (Biography of an Artist; Cracow:

Panshvowe Wydaw Naukowe, 1971) gives a lively account of the young years of Malinowski,

Witkiewicz, and Chwistek. Professor Raymond Firth's contributions on his work and life are of

course well known and highly recommended.

submitted 1 June 1985

accepted 20 November 1985

final version received 15 March 1986

570 arnerican ethnologist

You might also like

- Science and Spirituality 2Document37 pagesScience and Spirituality 2Samaksh KumarNo ratings yet

- Old Norse Element in Swedish RomanticismDocument212 pagesOld Norse Element in Swedish RomanticismTim GladuNo ratings yet

- Kolakowski - Interview (Danny Postel)Document7 pagesKolakowski - Interview (Danny Postel)Guilherme Gomez De AndradeNo ratings yet

- The Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the NazisFrom EverandThe Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the NazisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Wat Aleksander Lucifer UnemployedDocument140 pagesWat Aleksander Lucifer Unemployedlaurkaunissaare1919100% (1)

- Russian LiteratureDocument8 pagesRussian LiteratureCollege LibraryNo ratings yet

- A Diary in The Strict Sense of The TermDocument347 pagesA Diary in The Strict Sense of The Termbin100% (3)

- National Development in Romania and Southeastern Europe: Papers in Honor of Cornelia BodeaFrom EverandNational Development in Romania and Southeastern Europe: Papers in Honor of Cornelia BodeaNo ratings yet

- The Conscious Resistance - Reflections On Anarchy and SpiritualityDocument117 pagesThe Conscious Resistance - Reflections On Anarchy and SpiritualityAEMendez541No ratings yet

- Article 14 - Sections With ExplanationDocument10 pagesArticle 14 - Sections With ExplanationJennifer Ruelo100% (8)

- Prague in Danger: The Years of German Occupation, 1939-45: Memories and History, Terror and Resistance, Theater and Jazz, Film and Poetry, Politics and WarFrom EverandPrague in Danger: The Years of German Occupation, 1939-45: Memories and History, Terror and Resistance, Theater and Jazz, Film and Poetry, Politics and WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Firth - Introduction To Malinowski's DiaryDocument18 pagesFirth - Introduction To Malinowski's Diaryguo100% (1)

- A History of The Alans in The West (1973)Document186 pagesA History of The Alans in The West (1973)BogNS100% (2)

- Abduction Versus Inference To The Best ExplanationDocument3 pagesAbduction Versus Inference To The Best ExplanationkkadilsonNo ratings yet

- Pan-Slavism: RussianDocument231 pagesPan-Slavism: RussianDilek TzlNo ratings yet

- Pan Tadeusz: or The Last Foray in LithuaniaFrom EverandPan Tadeusz: or The Last Foray in LithuaniaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- In Light of Another's Word: European Ethnography in the Middle AgesFrom EverandIn Light of Another's Word: European Ethnography in the Middle AgesNo ratings yet

- Oath-Taking in Hungary, Central and Eastern EuropeDocument317 pagesOath-Taking in Hungary, Central and Eastern EuropemeteaydNo ratings yet

- Erasmus and The Age of Reformation by Huizinga, Johan, 1872-1945Document170 pagesErasmus and The Age of Reformation by Huizinga, Johan, 1872-1945Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Helena Wayne Mulheres Na Vida de MalinowskiDocument12 pagesHelena Wayne Mulheres Na Vida de MalinowskiMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Pan Tadeusz: Or, the Last Foray in Lithuania; a Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812From EverandPan Tadeusz: Or, the Last Foray in Lithuania; a Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812No ratings yet

- Memoirs of the Polish Baroque: The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek, a Squire of the Commonwealth of Poland and LithuaniaFrom EverandMemoirs of the Polish Baroque: The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek, a Squire of the Commonwealth of Poland and LithuaniaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Voyage of the Yacht, Dal: from Gdynia to Chicago, 1933-34From EverandThe Voyage of the Yacht, Dal: from Gdynia to Chicago, 1933-34No ratings yet

- Writing His Life Through The OtherDocument8 pagesWriting His Life Through The OtherAngelica CorreaNo ratings yet

- Blom KnorozovDocument9 pagesBlom KnorozovStrafford LuNo ratings yet

- Duke of Nevermore - Jaso12!3!1981 177 183Document8 pagesDuke of Nevermore - Jaso12!3!1981 177 183Ignacio Fernández De MataNo ratings yet

- Imperialism and Working-Class Readers in Leipzig, 1890–1914Document31 pagesImperialism and Working-Class Readers in Leipzig, 1890–1914Tasos84No ratings yet

- 20th- and 21st-Century British and American LiteratureDocument12 pages20th- and 21st-Century British and American LiteratureGianelitha Alexandra Romero QuedoNo ratings yet

- Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature - 4. Naturalism in EnglandFrom EverandMain Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature - 4. Naturalism in EnglandNo ratings yet

- Tatarkiewicz ReminiscencesDocument10 pagesTatarkiewicz ReminiscencesRafael París RestrepoNo ratings yet

- The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen's LondonFrom EverandThe Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen's LondonRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Studies in Medieval Philosophy, Science, and Logic: Collected Papers 1933–1969From EverandStudies in Medieval Philosophy, Science, and Logic: Collected Papers 1933–1969No ratings yet

- Psari U PVL PDFDocument12 pagesPsari U PVL PDFPpš MiroNo ratings yet

- Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí: Alezander CastrellonDocument4 pagesUniversidad Autónoma de Chiriquí: Alezander CastrellonJhosnot Ronal Alexander CastrellonNo ratings yet

- The Puritan Movement. in Its Broadest Sense The Puritan Movement May Be Regarded As ADocument11 pagesThe Puritan Movement. in Its Broadest Sense The Puritan Movement May Be Regarded As AKamala OinamNo ratings yet

- Towards a Scientific Theory of Culture: The Writings of Bronislaw MalinowskiFrom EverandTowards a Scientific Theory of Culture: The Writings of Bronislaw MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- English: 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World-Quarter 2Document12 pagesEnglish: 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World-Quarter 2Jessica BarguinNo ratings yet

- How Did The Ideas of Juri Lotman Reach The West?: A MemoirDocument10 pagesHow Did The Ideas of Juri Lotman Reach The West?: A MemoirFarih NourreNo ratings yet

- Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature: Naturalism in EnglandFrom EverandMain Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature: Naturalism in EnglandNo ratings yet

- Bartolomeus Kopitar and Josef DobrovskyDocument14 pagesBartolomeus Kopitar and Josef DobrovskyLegionarulNo ratings yet

- Pope John Paul IIDocument7 pagesPope John Paul IIHelenaNo ratings yet

- Sir MondDocument19 pagesSir MondAdouNo ratings yet

- The Pan-African Problem of Culture ContactDocument18 pagesThe Pan-African Problem of Culture ContactMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Anthropology's Conrad-Malinowski in The Tropics and WhatDocument24 pagesAnthropology's Conrad-Malinowski in The Tropics and WhatMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- The Political Thought of Bronislaw Malinowski - Ernest GellnerDocument3 pagesThe Political Thought of Bronislaw Malinowski - Ernest GellnerMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Some Reflections On Antrhropology's Missionary Positions - BurtonDocument10 pagesSome Reflections On Antrhropology's Missionary Positions - BurtonMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- The End of Informality - Jaro StaculDocument23 pagesThe End of Informality - Jaro StaculMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Malinowski and The New HumanismDocument18 pagesMalinowski and The New HumanismMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Bronislaw in South Tyrol - A Relational Biography of People, Places and WorksDocument17 pagesBronislaw in South Tyrol - A Relational Biography of People, Places and WorksMuseu da MONo ratings yet

- Amity Assignment ResearchDocument2 pagesAmity Assignment ResearchALI KHANNo ratings yet

- Name: Jamari Parker Student ID#: 0124159Document7 pagesName: Jamari Parker Student ID#: 0124159Isha PatelNo ratings yet

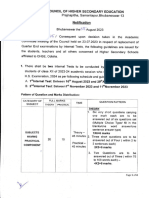

- Replacement of Quarter End Examinations by Internal TestsDocument4 pagesReplacement of Quarter End Examinations by Internal Testsrajakishore mohapatraNo ratings yet

- Mahdzar, S.S.B.S. (2008) Sociability Vs Accessibility Urban Street Life. Doctoral Thesis, University of London.Document434 pagesMahdzar, S.S.B.S. (2008) Sociability Vs Accessibility Urban Street Life. Doctoral Thesis, University of London.yoginireaderNo ratings yet

- WMO-Guidelines For The Assessment of Uncertainty of Hydrometric Measurements PDFDocument24 pagesWMO-Guidelines For The Assessment of Uncertainty of Hydrometric Measurements PDFzilangamba_s4535No ratings yet

- Literature Review Example Bachelor ThesisDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Example Bachelor Thesisdazelasif100% (1)

- GST 112 AssDocument8 pagesGST 112 AssUteh AghoghoNo ratings yet

- San Isidro Senior High School SurveyDocument4 pagesSan Isidro Senior High School SurveyLouise HenryNo ratings yet

- Unesco Technical PapersDocument315 pagesUnesco Technical PapersGerardo Maximiliano Medina QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- 4 Questions in Viva and DefenceDocument3 pages4 Questions in Viva and DefenceAbe MieNo ratings yet

- Reading Questions: Gilligan's in A Different VoiceDocument5 pagesReading Questions: Gilligan's in A Different VoiceJan Jamison ZuluetaNo ratings yet

- Aloysius ModernityDocument7 pagesAloysius ModernitySadique PK MampadNo ratings yet

- Public Forum: Richmon Allan B. GraciaDocument20 pagesPublic Forum: Richmon Allan B. GraciaRICHMON ALLAN B. GRACIANo ratings yet

- Fry - 2001 - Multifunctional Landscapes - Towards Transdisciplinary ResearchDocument10 pagesFry - 2001 - Multifunctional Landscapes - Towards Transdisciplinary ResearchDaniloMenezesNo ratings yet

- Writing Undergraduate Lab Reports: 20% DiscountDocument1 pageWriting Undergraduate Lab Reports: 20% DiscountSage of Six BowlsNo ratings yet

- ANALYSIS & DESIGN - Chen, Duan, Bridge Engineering Handbook, (CRC 1999) - 17Document1 pageANALYSIS & DESIGN - Chen, Duan, Bridge Engineering Handbook, (CRC 1999) - 17visanuNo ratings yet

- Antim Prahar Business Research MethodsDocument66 pagesAntim Prahar Business Research Methodsharshit bhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Classifying Geographical HistoryDocument14 pagesClassifying Geographical HistoryRubenNo ratings yet

- Historical Research: Reading in Philippine HistoryDocument14 pagesHistorical Research: Reading in Philippine HistoryLorven Jane Bustamante FloresNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observations What Will You Look For?Document6 pagesClassroom Observations What Will You Look For?Gamas Pura JoseNo ratings yet

- Dbms UPDATED MANUAL EWITDocument75 pagesDbms UPDATED MANUAL EWITMadhukesh .kNo ratings yet

- Self-Reflection-Chapter 1 ResearchDocument9 pagesSelf-Reflection-Chapter 1 ResearchSUUD ABDULLANo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Quantitative: CG Topic 4: Understanding Data and Ways To Systematically Collect DataDocument75 pagesPractical Research 2 Quantitative: CG Topic 4: Understanding Data and Ways To Systematically Collect DataNikkoJonesNo ratings yet

- MSC BFS Flyer - ForMedDocument2 pagesMSC BFS Flyer - ForMedShahid IrshadNo ratings yet

- 2022 Fall WOE FinalDocument24 pages2022 Fall WOE FinalhussainahmadNo ratings yet

- Ranbaxy - Annual Report 2007Document140 pagesRanbaxy - Annual Report 2007Saurabh ChandraNo ratings yet