Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Book Reviews JOYA CHATTERJI Bengal Divid

Uploaded by

Tanvir AhmedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Reviews JOYA CHATTERJI Bengal Divid

Uploaded by

Tanvir AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

Indian Economic & Social History

Review

http://ier.sagepub.com

Book Reviews : JOYA CHATTERJI, Bengal Divided: Hindu

Communalism and Partition, 1932-1947, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, 1994, 303 pp

Indivar Kamtekar

Indian Economic Social History Review 1996; 33; 347

DOI: 10.1177/001946469603300306

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ier.sagepub.com

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Indian Economic & Social History Review can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ier.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ier.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.in/about/permissions.asp

Downloaded from http://ier.sagepub.com at UNIV ARIZONA LIBRARY on July 29, 2009

347

because of the line drawings and photographs which accompany the

text.

Nandini Sundar

JOYA CHATTERJI, Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition,

1932-1947, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, 303 pp.

This book tells the sad story of Bengal’s bhadralok. According to Chatterji,

their decline in the last fifteen years of British rule was both political and

economic. The Communal Award of 1932 gave Muslims more seats than

Hindus in Bengal’s legislature, reducing to bhadralok to a minority in an

Assembly they expected to dominate. The Government of India Act 1935

substantially expanded the electorate, pulled the mofussil into the arena,

enfranchised many rich peasants, and thus increased the importance of

Muslims in Bengal’s politics. In their effort to counter this and sustain their

position, the bhadralok leaders tried to create a unified Hindu constituency;

this forced them to solicit the support of the lower castes whom they

despised. The economic nail in the Bhadralok coffin was the Depression,

which made the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Bengal unable to

repay loans, or reluctant to part with the rent that contributed to bhadralok

income. Muslims also began to make inroads into the bhadralok share of

government jobs and their control over education.

Chatterji sees the Bengal Congress as the party of the bhadralok. It was

urban, elitist, communal, and committed to protecting zamindari rights.

While the radicals were more noisy, the conservatives were more numerous.

When this urban party needed to win a rural vote, Sarat Bose tried to shift

its programme and expand its social base; but the expulsion of the Bose

group from the Congress in 1939 confirmed its conservative and communal

character. As the Hindus were a minority in Bengal, the bhadralok feared

that democracy would damage them, and favoured minority rights and

safeguards. Therefore, measures desired by the All-India Congress were

detested by the Bengal Congress. This predicament, difficult to transcend,

kept the all-India party and the Bengal Congress out of tune.

Forced to retreat on all fronts, and fearing that their nightmare of

Muslim domination might become reality, the bhadralok abandoned their

broad nationalism for narrow communalism. This was a way of trying to

regain their influence. The bhadralok therefore supported partition. Parti-

tion was a considered Hindu choice, advocated and indeed demanded by

the Congress party, rather than a purely Muslim one, as is, commonly

believed. The crowning evidence presented for this, discovered in the

Downloaded from http://ier.sagepub.com at UNIV ARIZONA LIBRARY on July 29, 2009

348

All-India Congress Committee papers at the Nehru Museum Library in

Delhi, is a collection of petitions from Hindus in Bengal to the president of

the AICC, asking for partition. Chatterji argues that Leonard Gordon is

mistaken in attributing the pro-partition campaign to the Hindu Mahasabha:

’In fact, the Bengal Congress was the chief organiser of the campaign for

the partition of Bengal’ (p. 249). By the mid-1940s, there was little to

distinguish the Bengal Congress from the Mahasabha, in its defence of

Hindu interests. Hardly anyone had any time for the United Bengal

Scheme, promoted by Sarat Bose and Suhrawardy, quixotically envisaging

a sovereign and undivided Bengal. So the bhadralok, who had vehemently

opposed the partition of Bengal in 1905, supported it in 1947.

The first part of this book, dealing with the Communal Award and the

Government of India Act, follows the lines of argument set out in the

epilogue of J.H. Broomfield’s Elite Conflict in a Plural Society: Twentieth

Century Bengal (Berkeley, 1968), where he describes ’legislative attacks’

on bhadralok power. Here the analysis is on the whole convincing, though

in addition to legislatures and local institutions, there is also a case for

looking at trade unions, student associations, the Communist Party of

India, and the leadership of mass movements: many of the bhadralok

peered away from legislative politics, and that should form part of this

story. The indices of economic decline also need to be identified. Was the

bulk of bhadralok income from land, or from salaries? The Depression,

with its fall in food prices, was not such a catastrophe for Indians with

salaries in the cities; rather, it was wartime inflation which hurt the salaried

classes (but the war also increased employment, benefiting the unemployed

among the bhadralok). Some account needs to be taken of the impact of

the war, and greater account needs to be taken of differentiation within the

bhadralok. What is documented and brought out extremely well is the

specificity of the Bengal Congress, its contradictions and contortions, and

the conflicts with the Congress High Command. In short, the decline

hypothesis is plausible, but needs a firmer backing, especially of economic

history.

The argument on Hindu communalism is interesting and sharp. Rather

than positing a shift from nationalism to communalism, it is, however,

better to see the two as coexisting: during 1946 both exploded in demon-

strations and riots on the streets of Calcutta. Many of Bengal’s Hindus

wanted partition, but did they all want it? The petitions cited are over-

whelmingly from areas in Hindu-majority West Bengal. This is logical, as

the bhadralok of Muslim-majority East Bengal were unlikely to be enthusi-

astic about a partition which might endanger their zamindaris. What was

the reasoning of those Hindus who did desire partition? Previous work has

emphasised the immediate political impact of the 1946 killings, suggesting

that the Great Calcutta Killing made Hindus feel unsafe; Chatterji, by

contrast, emphasises a longer process of bhadralok decline.

Downloaded from http://ier.sagepub.com at UNIV ARIZONA LIBRARY on July 29, 2009

349

The Hindu demand for partition came, however, very late in the day, in

the last months of British rule. This is all-important. The situations in 1905

and 1947 were completely different. 1905 concerned the partition of a

province; 1947 concerned the partition of a nation. If the bhadralok

demanded the partition of Bengal in 1947, it was because they believed the

partition of India to be inevitable (the demand for a United Independent

Bengal was a non-starter). They were not asking for the partition of the

country, but for the partition of the province if the country was to be

partitioned. To miss the conditionality of the demand is to misjudge the

whole issue. The burning question, and the real choice before the bhadralok,

was whether they were to be part of the Indian or Pakistani states, and

their desire for the division of the province must be viewed in this context.

It did not mean that they wanted to partition India; it meant that they did

not want to be part of Pakistan.

Bengal Divided is a thought-provoking and valuable book. With refreshing

skepticism, it questions the self-image of the social group studied. Sources

like the Bengal Police records and the Bengal Home Department records

are fruitfully used, with abundant detail lucidly presented. The book offers

a clear and coherent-if partially disputable-thesis. It succeeds in placing

bhadralok decline and bhadralok communalism firmly on the research

agenda. This work establishes the author as an authority on modern

Bengal’s political history. The author claims that the originality of her

work lies in looking at partition from a provincial point of view, and at the

role Hindu communalism played. Yet her work also reminds us to look,

not just at why the dramatic events of 1947 happened, but at what happened

to the people who could do little about them.

Indivar Kamtekar

Centre for Historical Studies

Jawaharlal Nehru University

EUGENE F. IRSCHICK, Dialogue and History: Constructing South India,

1795-1895, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles,

1994.

The author of this book questions the argument put forward by such

scholars as Edward Said that the view constructed in the colonial period of

the local society was a product of European values imposed on a subordinate

colonised society. By analysing how people created knowledge regarding

space and cultural identity in a south Indian district, later called Chingelput,

Dr Irschick instead convincingly demonstrates that the British and

local

agricultural groups interacted in this heteroglot and dialogic process of

cultural formation and that, therefore, the view thus formed was neither

Downloaded from http://ier.sagepub.com at UNIV ARIZONA LIBRARY on July 29, 2009

You might also like

- Dwaipayan Sen - No Matter How, Jogendranath Had To Be DefeatedDocument45 pagesDwaipayan Sen - No Matter How, Jogendranath Had To Be DefeatedAnirban GhatakNo ratings yet

- Voices in the Wilderness: Critiquing Indian Constituent Assembly DebatesFrom EverandVoices in the Wilderness: Critiquing Indian Constituent Assembly DebatesNo ratings yet

- Colonialism Politics of Language and Partition of BengalDocument74 pagesColonialism Politics of Language and Partition of BengalShahid Ul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Muslim Politics in Bihar Changing Contours (Mohammad Sajjad)Document397 pagesMuslim Politics in Bihar Changing Contours (Mohammad Sajjad)uvaisahamedNo ratings yet

- Why Study The Literatures of The Partition (1947) ?: Subhor NjanDocument16 pagesWhy Study The Literatures of The Partition (1947) ?: Subhor NjanHeather CarterNo ratings yet

- Fazlul Haq and AlternativeDocument38 pagesFazlul Haq and AlternativecbacademicsNo ratings yet

- 3 Communal Riots in IndiaDocument36 pages3 Communal Riots in IndiaGRACE JOSEPHNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument80 pagesChapterapurba mandalNo ratings yet

- Allah Baksh Versus SavarkarDocument2 pagesAllah Baksh Versus SavarkarChessellPiquet100% (1)

- A Partition of Contingency Public Discourse in Bengal, 1946-47Document40 pagesA Partition of Contingency Public Discourse in Bengal, 1946-47Subarno PandeNo ratings yet

- 3 Communal Riots in IndiaDocument35 pages3 Communal Riots in IndiaFahad UsmaniNo ratings yet

- Rural India Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarDocument12 pagesRural India Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarMarcos MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Role of Jinnah in PartitionDocument4 pagesRole of Jinnah in PartitionPradipta KunduNo ratings yet

- Allah Baksh Versus SavarkarDocument4 pagesAllah Baksh Versus SavarkarAnilNauriyaNo ratings yet

- Sacred Symbol As Mobilizing Ideology The North Indian Search For A Hindu CommunityDocument30 pagesSacred Symbol As Mobilizing Ideology The North Indian Search For A Hindu CommunityfizaisNo ratings yet

- The Swadeshi Movement: Nationalism in Bengal 1905-1908Document25 pagesThe Swadeshi Movement: Nationalism in Bengal 1905-1908Rishali ChauhanNo ratings yet

- North South University Student's Coursework on Bengali Nationalism and HistoryDocument7 pagesNorth South University Student's Coursework on Bengali Nationalism and HistoryAhanaf FaminNo ratings yet

- Sabhyasachi Amiyo ReviewDocument12 pagesSabhyasachi Amiyo ReviewBipul BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Hindus and Muslims in Historical IndiaDocument17 pagesDifferences Between Hindus and Muslims in Historical IndiaJuanid AsgharNo ratings yet

- 4 2 KaDocument17 pages4 2 KaMUSKAN AGARWALNo ratings yet

- Muslim Resistance to Communal Separatism in BiharDocument15 pagesMuslim Resistance to Communal Separatism in BiharManojNo ratings yet

- Muslim League Leader Khwaja Nazim Uddin and 1937 EDocument6 pagesMuslim League Leader Khwaja Nazim Uddin and 1937 Emuhammadwaseem1759No ratings yet

- Democracy against Development: Lower-Caste Politics and Political Modernity in Postcolonial IndiaFrom EverandDemocracy against Development: Lower-Caste Politics and Political Modernity in Postcolonial IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Anglo Indians and The Punjab Partition IDocument33 pagesAnglo Indians and The Punjab Partition IafatqiamatNo ratings yet

- Partition and Indian Literature Chaman LalDocument17 pagesPartition and Indian Literature Chaman LalAgrimaNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 5 PDFDocument30 pages10 - Chapter 5 PDFGiyasul IslamNo ratings yet

- Jogendranath Mandal and The Politics of PDFDocument18 pagesJogendranath Mandal and The Politics of PDFOmar BaigNo ratings yet

- The Sikhs in History by Dr. Sangat SinghDocument453 pagesThe Sikhs in History by Dr. Sangat SinghSikh Texts100% (2)

- SSRN Id3549805Document14 pagesSSRN Id354980549 FdNo ratings yet

- Researchgate publication on peasant and tribal movements in colonial BengalDocument17 pagesResearchgate publication on peasant and tribal movements in colonial BengalNeha GautamNo ratings yet

- Bhagat Singh As SatyagrahiDocument11 pagesBhagat Singh As SatyagrahiShreya RakshitNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument31 pagesHistoryProdosh HaldarNo ratings yet

- Babasaheb Ambedkar: A Dalit Leader or A National Leader: A Critical AnalysisDocument5 pagesBabasaheb Ambedkar: A Dalit Leader or A National Leader: A Critical Analysisa86092067No ratings yet

- Verrier Elwin by R C GUHADocument14 pagesVerrier Elwin by R C GUHAAnish AgnihotriNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The Partition of BangalDocument14 pagesAnalysis On The Partition of BangalZubair MadniNo ratings yet

- Ambedkar GitaDocument16 pagesAmbedkar GitaAcharya G Anandaraj100% (1)

- Communal Riots in BengalDocument3 pagesCommunal Riots in BengalSonal SinghNo ratings yet

- Ambedkar's Views On UntouchabilityDocument45 pagesAmbedkar's Views On Untouchabilityanilkumarduvvuru100% (1)

- India-Pakistan Partition by Kanwaljit KaurDocument13 pagesIndia-Pakistan Partition by Kanwaljit KaurReadnGrowNo ratings yet

- A Review of Dr. B R Ambedkar's Social IdeologyDocument11 pagesA Review of Dr. B R Ambedkar's Social IdeologyIshita KothariNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh StudiesDocument31 pagesBangladesh StudiesSabbir HossenNo ratings yet

- GEBS101 3. Reconsideration of Discovery of Bangladesh Akbar Ali Khan - MIST ME UG SJS 2020DECDocument39 pagesGEBS101 3. Reconsideration of Discovery of Bangladesh Akbar Ali Khan - MIST ME UG SJS 2020DECnishanderoyalNo ratings yet

- How Accurate Was Clement Attlee in His Assertion That The Indian National Army Was The Principal Reason For Britain's Withdrawal From India in 1947?Document50 pagesHow Accurate Was Clement Attlee in His Assertion That The Indian National Army Was The Principal Reason For Britain's Withdrawal From India in 1947?David Tomlinson100% (6)

- Caste and Class in IndiaDocument311 pagesCaste and Class in IndiasaturnitinerantNo ratings yet

- Growth of Communalism in IndiaDocument54 pagesGrowth of Communalism in IndiaChetan Aggarwal100% (1)

- Rise of communalism in India 1920-1947Document5 pagesRise of communalism in India 1920-1947smrithi100% (2)

- Urdu-Hindi Controversy (1867) : Emergence of 'Two Nation Theory'Document11 pagesUrdu-Hindi Controversy (1867) : Emergence of 'Two Nation Theory'Bilal Akhter100% (1)

- Chapter - 2 Discourses of Nation / NationalismDocument54 pagesChapter - 2 Discourses of Nation / NationalismShruti RaiNo ratings yet

- M. A Political Science Iind Sem (202) Jharkhand MovementDocument6 pagesM. A Political Science Iind Sem (202) Jharkhand MovementbibinNo ratings yet

- Ideological, Cultural, Organisational and Economic Origins of Bengali Separatist MovementDocument20 pagesIdeological, Cultural, Organisational and Economic Origins of Bengali Separatist MovementMH. SyarifNo ratings yet

- Two Nations Theory, Negotiations On Partition of India and PakistanDocument26 pagesTwo Nations Theory, Negotiations On Partition of India and PakistanRishali ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Bik Ash Deb Article in Social TrendsDocument39 pagesBik Ash Deb Article in Social TrendsDebdeep SinhaNo ratings yet

- 421165Document30 pages421165Anonymous rvBXIDNo ratings yet

- History I - Mughal Sikh ConflictDocument26 pagesHistory I - Mughal Sikh ConflictPrateek Mishra100% (2)

- Formation of Communist Thought in IndiaDocument176 pagesFormation of Communist Thought in IndiaMomalNo ratings yet

- B R Ambedkar S Idea On Equality and Freedom An Indian Perspective PDFDocument9 pagesB R Ambedkar S Idea On Equality and Freedom An Indian Perspective PDFvidushiiiNo ratings yet

- A.R. Desai's Marxist Sociological AnalysisDocument33 pagesA.R. Desai's Marxist Sociological AnalysisAvinashKumarNo ratings yet

- WSFR Ir 9 Ir 12 Fact SheetDocument4 pagesWSFR Ir 9 Ir 12 Fact Sheetapi-507949775No ratings yet

- Ancient+Greek+Society+ +World+History+EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesAncient+Greek+Society+ +World+History+EncyclopediaElliot ReichardtNo ratings yet

- Report SipriDocument12 pagesReport SipriDavide FalcioniNo ratings yet

- Bangalore University Memorial Challenges Validity of Marriage Reforms OrdinanceDocument32 pagesBangalore University Memorial Challenges Validity of Marriage Reforms OrdinanceAnushka VermaNo ratings yet

- Stupid Is ForeverDocument24 pagesStupid Is ForeverKimberlyPlazaNo ratings yet

- Reconstructions - Amalgamation, Mergers, TakeoversDocument5 pagesReconstructions - Amalgamation, Mergers, Takeoversmasiga mauriceNo ratings yet

- Cultural Studies and The Centre: Some Problematics and Problems (Stuart Hall)Document11 pagesCultural Studies and The Centre: Some Problematics and Problems (Stuart Hall)Alexei GallardoNo ratings yet

- GJERDINGEN - The Future of Legal Scholarship and The Search For A Modern TheorDocument99 pagesGJERDINGEN - The Future of Legal Scholarship and The Search For A Modern TheorFarrah HabibieNo ratings yet

- The Organisation of The Independent State of Croatia's Administrative BranchDocument13 pagesThe Organisation of The Independent State of Croatia's Administrative BranchLamijaBesirovicNo ratings yet

- Socialist Tentacles in Alberta Education: H. C. Newland, Supervisor of SchoolsDocument2 pagesSocialist Tentacles in Alberta Education: H. C. Newland, Supervisor of SchoolsMichael WagnerNo ratings yet

- Joselito Peralta Y Zareno, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, Respondent. DecisionDocument5 pagesJoselito Peralta Y Zareno, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, Respondent. DecisionGinn UndarNo ratings yet

- Letter No 008 Reply by Authority EngineerDocument8 pagesLetter No 008 Reply by Authority EngineerAbhishek BhandariNo ratings yet

- Fam 020 PDFDocument2 pagesFam 020 PDFCrystalNo ratings yet

- Class-2-3rd Term-MathematicsDocument14 pagesClass-2-3rd Term-MathematicsHabibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Ebook Economic Way of Thinking 13Th Edition Heyne Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument44 pagesEbook Economic Way of Thinking 13Th Edition Heyne Test Bank Full Chapter PDFkhondvarletrycth100% (8)

- Annual Return For A Company Limited by GuaranteeDocument4 pagesAnnual Return For A Company Limited by GuaranteeAtisang Tonny SethNo ratings yet

- Policy Schedule Personal Accident Insurance Policy: (Plan 5)Document2 pagesPolicy Schedule Personal Accident Insurance Policy: (Plan 5)Rana BiswasNo ratings yet

- Capitol Wireless V Prov TreasurerDocument13 pagesCapitol Wireless V Prov TreasurerDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- Shelley Walia: On Rights For AllDocument1 pageShelley Walia: On Rights For AllvishuNo ratings yet

- Veer PetitionerDocument19 pagesVeer Petitionerpriyanka100% (1)

- Factors Affecting Folk DanceDocument2 pagesFactors Affecting Folk DanceSheryll80% (10)

- Aznar vs. COMELEC G.R. No. 83820Document2 pagesAznar vs. COMELEC G.R. No. 83820theresaNo ratings yet

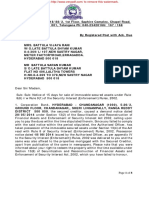

- 1546 Battula Vijaya Rani PDFDocument8 pages1546 Battula Vijaya Rani PDFSneha AdepuNo ratings yet

- Overseas Filipino WorkerDocument2 pagesOverseas Filipino WorkerMonica HermoNo ratings yet

- STATCON Prelims Reviewer PDFDocument42 pagesSTATCON Prelims Reviewer PDFLes PaulNo ratings yet

- Petition For Issuance of The Writ of KalikasanDocument12 pagesPetition For Issuance of The Writ of KalikasanInnoKalNo ratings yet

- Democracy & Justice: Collected Writings 2019Document133 pagesDemocracy & Justice: Collected Writings 2019The Brennan Center for JusticeNo ratings yet

- Lec - 20 On GPSC RTO Class 2 & 3 Acts/Rules/Guideline/Institute/JudgementsDocument22 pagesLec - 20 On GPSC RTO Class 2 & 3 Acts/Rules/Guideline/Institute/JudgementsHaveNo ratings yet

- Finance Department: Section Officer AdmnDocument438 pagesFinance Department: Section Officer AdmnRam ReddyNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Education: A Challenge To Global Teachers: (Reflection)Document3 pagesMulticultural Education: A Challenge To Global Teachers: (Reflection)Florencio Diones Delos Santos Jr.No ratings yet