Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Demographic Data

Uploaded by

Neha ChawlaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Demographic Data

Uploaded by

Neha ChawlaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE IMPORTANCE OF COLLECTING DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

Dr. Rashawn Ray

David M. Rubenstein Fellow, The Brookings Institution

Chairwoman Velázquez, Ranking Member Chabot, and distinguished members of the Committee

on Small Business, thank you for inviting me to testify on “Enhancing Patent Diversity for

America’s Innovators.” I am a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at The Brookings Institution. I am

also an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland and the Executive

Director of the Lab for Applied Social Science Research (LASSR). LASSR is a research center

that regularly partners with government agencies, organizations, and corporations to conduct

objective research evaluations and develop innovative research products such as our virtual

reality work with law enforcement and incarcerated people.

My comments will center on the voluntary collection of demographic data. My written testimony

will primarily focus on three specific questions: 1) What are public attitudes and behaviors

regarding the collection of demographic data? 2) Is the collection of demographic data

important? and 3) What do we know about United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)

patent assignees?

What are the Public Attitudes and Behaviors regarding Demographic Data?

A majority of Americans want to be in control of who collects data on them, what is collected,

and for how long the data are stored.1 However, context matters. For example, 90% of

Americans view their social security number as very sensitive whereas only eight percent view

their purchasing habits as very sensitive.2 People are also willing to provide information about

their political and religious views. At the same time, Americans are becoming accustomed to

limited control over their information. About 80% of Americans report having awareness about

the government collecting information about verbal, written, and online communication.

Roughly 50% of people in a Pew survey reported having little to no control over that

information. Overall, what most Americans desire is more transparency about what data is

collected, how long it will be stored, and what those data will be used for.

People seem to be quite comfortable with credit card companies collecting and storing data on

them, followed closely by the government. They are much less likely to be comfortable with

websites they visit online as well as cable and cell phone companies collecting and storing

information on them. In fact, over 50% of Americans think that the government should be able to

store data for a few years or as long as they need to. Still, people are not confident about the

1 Madden, Mary and Lee Raine. 2015. “America’s Views about Data Collection and Security.” Pew Research

Center. < https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/05/20/americans-views-about-data-collection-and-security/>

(accessed on January 13, 2020).

2Madden, Mary. 2014. “Public Perceptions of Privacy and Security in the Post-Snowden Era.” Pew Research

Center.” < https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2014/11/12/public-privacy-perceptions/> (accessed on January 13,

2020).

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 1

privacy and security of their data from any source. Slightly less than one-third of Americans

perceive the government will keep their data safe and private. This is comparable to views about

cell phone and cable companies.

Over 50% of Americans say they have very little or no understanding about data protection

laws,3 and 75% say there should be more regulation. People disapprove of the government

collecting their phone and email records. Part of this simply has to do with a decline in public

trust in social institutions.4 However, the public is much more likely to trust science and

medicine than other social institutions.

Despite people’s attitudes about data collection, how do people actually behave? Do people

actually voluntary provide demographic information on a survey when asked? In short, yes.

My experience collecting data is that people overwhelmingly answer demographic questions on

surveys. I have conducted surveys and interviews with the general public, police officers,

families, parents, employees of companies, members of religious organizations, government

employees, protesters and march attendees, people who have lost large amounts of weight,

people living in urban, suburban, and rural areas, people living in the Midwest, on the west coast,

in the south, and in the northeast, and high risk groups. I have conducted these surveys and

interviews in-person, online, on paper, and on tablets and other smart devices. I have asked

demographic questions verbally too and the response rate is similar.

Generally, I have asked respondents about an assortment of topics ranging from discussions

about police-community relations to marital and relationship issues to sexual assault on college

campuses. No matter the topic, people still overwhelmingly volunteer their demographic

information. I typically ask respondents their gender, age, race/ethnicity, national origin, sexual

orientation, education level, household income, military or veteran status, and disability. I have

also asked people about who lives in their household as well as their political and religious

beliefs. In a typical survey, less than 5% of respondents refuse to answer demographic questions.

I am also the co-editor of an academic publication, Contexts Magazine: Sociology for the Public,

and have authors who publish on a range of topics. No matter how obscure, rarely do the

researchers report having difficulty getting respondents to answer demographic questions.

Additionally, there are large datasets that social scientists commonly utilize such as the General

Social Surveys, which has been asked since the 1970s. People regularly provide answers to

demographic questions on these surveys. A government survey, such as the U.S Census, that

3Auzier, Brooke And Lee Rainie. 2019. “Key Takeaways on Americans’ Views about Privacy, Surveillance and

Data-sharing.” Pew Research Center. < https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/15/key-takeaways-on-

americans-views-about-privacy-surveillance-and-data-sharing/> (accessed on January 13, 2020).

4 McGeeney, Kyley, Brian Kriz, Shawnna Mullenax, Laura Kail, Gina Walejko, Monica Vines, Nancy Bates, and

Yazmín García Trejo. 2019. “2020 Census Barriers, Attitudes, and Motivators Study Survey Report.” United States

Census Bureau. < https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/final-analysis-

reports/2020-report-cbams-study-survey.pdf> (accessed January 13, 2020).

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 2

collects a series of demographic data is also useful to note.5 Ninety percent of Americans view

the Census as very or somewhat important. And, over 80% of Americans say they definitely or

probably will participate in it. Interestingly, I had to fill out a demographic data form to be here

today. I did not think twice about filling it out, similar to most Americans. I think it is safe to say

that Americans are more than willing to provide their demographic data.

Why is it Important to Collect Demographic Data?

Collecting demographic data is important for a few central reasons. First, more data is normally

better because they help to eliminate false positives. For example, the lack of demographic data

may inflate the likelihood of certain groups catching a deadly disease, having an early onset of

dementia, or having a child with autism. These false positive may inadvertently funnel resources

to the wrong areas. Second, the collection of demographic data allows for the determination of

whether a sample is representative. If researchers are conducting a study on vaccines, for

example, a representative sample is paramount. If there is under- or over-representation of

certain groups, the analysis will likely over or underestimate the impact of those vaccines. Third,

there is a long and torrid history of the consequences of not collecting demographic data on real

life outcomes that have shifted public opinion. Certain groups have historically and

systematically been left out of the data collection process. What many Americans desire more

than anything is transparency, inclusion, and equity. Demographic data help to provide this. A

lack of demographic data often leads to bad science, does a disservice to Americans, and inhibits

the United States’ ability in continuing to be innovative and comprehensive.

In the case of patents, demographic data could show us whether certain groups are more or less

likely to apply and receive patents. Demographic data may show that the percentage of women

and racial minorities who apply for patents are lower than their percentage in the U.S.

population. But, demographic data may show that the percentage of women and racial minorities

who apply for patents is on par with their percentage in certain STEM fields. Demographic data

may show that people with lower levels of education are applying for patents but less likely to

receive them. This may suggest that people with higher levels of education may have more

knowledge and expertise about the patent process that leads to a higher level of success. We do

have some information about inventors that is important to share that may help shed light on

some of these propositions.

What do we know about who is Awarded Patents?

The National Science Foundation provides some data on patent assignees (inventors and owner

of patents) from 2000-2016 from USPTO.6 I provide graphs for ease of use. Figure 1 shows the

number of patents by U.S. versus foreign owners during this period. Though the number of

assignees suggest parity between U.S. and foreign inventors, the percentages in Figure 2 suggest

a different story. The percentage of U.S. inventors has decreased over time, while the percentage

5Pew Research Center. 2010. “Most View Census Positively, But Some Have Doubts.” < https://www.people-

press.org/2010/01/20/most-view-census-positively-but-some-have-doubts/> (accessed on January 13, 2020).

6 National Science Foundation. 2018. “Invention, Knowledge Transfer, and Innovation.” <

https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/report/sections/invention-knowledge-transfer-and-

innovation/invention-united-states-and-comparative-global-trends> (accessed on January 13, 2020).

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 3

of foreign inventors has increased. With additional demographic data, policymakers may want to

know whether the proportion of U.S. versus foreign applicants shows a similar pattern.

Figure 1: Number of USPTO Patents Granted by Owner,

2002-2016

160,000

140,000

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

Assigned to foreign owner Assigned to U.S. owner

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics; SRI

International; Science-Metrix; PatentsView and USPTO patent data, Science and Engineering Indicators

2018; Accessed January 2020.

Figure 2: Percentage of USPTO Patents Granted by

Owner, 2002-2016

60%

58%

56%

54%

52%

50%

48%

46%

44%

42%

40%

200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013201420152016

Assigned to foreign owner Assigned to U.S. owner

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics; SRI

International; Science-Metrix; PatentsView and USPTO patent data, Science and Engineering Indicators

2018; Accessed January 2020.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of USPTO patents granted by world region from 2000-2016. As

noted above, the percentage of U.S. assignees has decreased over time. The rest of Northern,

Southern, and Central America has stayed relatively stable at less than three percent. Besides the

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 4

U.S., most of the patent assignees from the Americas come from Canada. Africa, Middle East,

and Australia has increased slightly from over one percent to over 2 percent. Israel is the main

representative from this region. Europe has decreased slightly from 17.2% in 2000, dipping to

14.4% in 2009, and then increasing to 16.2% in 2016. Germany followed by the United

Kingdom are the main assignees from Europe. Asia, primarily represented by inventors from

Japan, have encompassed at least 25% of assignees each year. Asian inventors have represented

nearly one-third of assignees every year since 2008. With additional demographic data,

policymakers may want to know the educational trajectories (university affiliations) of assignees.

That piece of demographic information may provide useful insights about inventors from other

regions of the world.

Figure 4 shows the number of USPTO patent assignees for U.S. owners. It shows a substantial

increase in the number of patents assigned to people in the private sector. The number of

inventors classified as individuals has decreased over time. The number of patent assignees from

the government remains low. The number of patents to U.S. universities has increased over the

past 15 years. In 2016, slightly over one-third of patents to U.S. universities were for

pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and medical technology.

Figure 3: USPTO Patents Granted by World Region,

2000-2016

60%

40%

20%

0%

United States America except US

Europe Asia

Africa, Middle East, and Australia

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics; SRI

International; Science-Metrix; PatentsView and USPTO patent data, Science and Engineering Indicators

2018; Accessed January 2020.

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 5

Figure 4: Number of USPTO Patents Granted by Sector

for U.S. Owners, 2002-2016

140,000

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

0

Private Individual Academic

Government Other Unclassified

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics; SRI

International; Science-Metrix; PatentsView and USPTO patent data, Science and Engineering Indicators

2018; Accessed January 2020.

In addition to government records about national origin and sector of inventors, some researchers

and organizations have aimed to gain information about gender and race by examining the names

of inventors. More recent research has aimed to estimate women’s patent activity and impact by

estimating their proportional representation on a patent based on the number of inventors listed.

The Institute for Women’s Policy Research has done extensive research in this area.

Results show some notable trends as they pertain to gender.7 First, the number of women listed

on patents still remains significantly low, despite increasing from less than 2,000 in the 1970s to

over 20,000 by 2010. Second, the number of patents with no women listed also increased from

the late 1970s to 2010. In 2010, nearly 100,000 patents had no women listed as inventors. Third,

women inventors are more likely to be in the sectors of apparel and jewelry rather than

technology and pharmaceuticals. Fourth, men are more likely to apply for patents relative to

women.

However, the gender gap seems to not solely be about who applies for a patent. There is a gender

gap in patent acceptance rates. While 73% of men had their patents accepted from 2002-2016,

only 67% of women did. This means that women are nearly 10% less likely to have a patent

accepted. When a woman is the primary assignee, the patent is rejected roughly 30% of the time,

compared to slightly less than 20% when the main patent assignee is a man. These results are

7 Milli, Jessica Milli, Emma Williams-Baron, Meika Berlan, Jenny Xia, and Barbara Gault. 2016. “Equity in

Innovation: Women Inventors and Patents.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <

https://iwpr.org/publications/equity-in-innovation-women-inventors-and-patents/> (accessed January 13, 2020).

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 6

troubling considering that women-owned firms have increased four times that of men over the

past 20 years but still represent roughly one-fifth of employer firms.8

An examination of race showed that less than 1,000 inventors of over 1 million were Black. 9

Black and Hispanic college graduates are less than half as likely to hold a patent relative to their

White counterparts. 10 Children born in poverty are 10 times less likely than children born to the

most affluent families to receive a patent. Still, Black and Hispanic men, compared to White and

Asian men, are less likely to have their patents accepted. But, Black men are more likely than

Black women to apply for patents. The intersection of race and gender matters in this context

considering that minority women firms are mostly driving the increase in women-owned firms.

College degrees do play a role in patent applications and gender disparities. While the number of

women obtaining degrees in biology and engineering increased from the late 1970s-2010, the

number of women obtaining computer science degrees decreased. However, degree is not the

only issue. There are leaks in the pipeline that cannot be adequately identified because the U.S

government does not currently collect demographic data. It is clear that disparities extend from

who applies to who is ultimately awarded a patent.

Collecting demographic data can help fill these important gaps, create more understanding and

equity in the process,11 and better streamline resources for trainings and funding so all

Americans can assist the United States in continuing to be a major world innovator for new

products that can help drive the economy and create jobs.

8 Williams-Baron, Emma, Jessica Milli, and Barbara Gault. 2018. “Innovation and Intellectual Property among

Women Entrepreneurs.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research. < https://iwpr.org/publications/innovation-

intellectual-property-women-entrepreneurs/> (accessed January 13, 2020).

9Cook, Lisa D. and Chaleampong Kongcharoen. 2010. The Idea Gap in Pink and Black. Michigan State University.

<https://www.msu.edu/~lisacook/pink_black_0810.pdf> (accessed January 13, 2020).

10Fechner, Holly and Matthew S. Shapanka. 2018. Closing Diversity Gaps in Innovation: Gender, Race, and Income

Disparities in Patenting and Commercialization of Inventions.” Technology and Innovation, 19: 727-734.

11Shaw, Elyse Shaw and Cynthia Hess. 2018. “Closing the Gender Gap in Patenting, Innovation, and

Commercialization: Programs Promoting Equity and Inclusion.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <

https://iwpr.org/publications/gender-diversity-patenting-program-scan/> (accessed January 13, 2020).

Dr. Rashawn Ray, The Brookings Institution 7

You might also like

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Methods of Studying DevianceFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Methods of Studying DevianceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- How We Became Our Data: A Genealogy of the Informational PersonFrom EverandHow We Became Our Data: A Genealogy of the Informational PersonNo ratings yet

- The Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionFrom EverandThe Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionNo ratings yet

- Identity Crisis: How Identification is Overused and MisunderstoodFrom EverandIdentity Crisis: How Identification is Overused and MisunderstoodNo ratings yet

- Between Movement and Establishment: Organizations Advocating for YouthFrom EverandBetween Movement and Establishment: Organizations Advocating for YouthNo ratings yet

- Project Syndicate - Org Aleksander DardeliDocument3 pagesProject Syndicate - Org Aleksander Dardeligh4 gh4No ratings yet

- A House Divided: What Would We Have to Give Up to Get the Political System We Want?From EverandA House Divided: What Would We Have to Give Up to Get the Political System We Want?No ratings yet

- The Blind Scientist: Unmasking the Misguided Methodology of Neo-DarwinismFrom EverandThe Blind Scientist: Unmasking the Misguided Methodology of Neo-DarwinismNo ratings yet

- Collection of Sources For Youth Voters 1Document6 pagesCollection of Sources For Youth Voters 1api-456181564No ratings yet

- Epidemic: America's Trade in Child RapeFrom EverandEpidemic: America's Trade in Child RapeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- On the Principles of Social Gravity [Revised edition]: How Human Systems Work, From the Family to the United NationsFrom EverandOn the Principles of Social Gravity [Revised edition]: How Human Systems Work, From the Family to the United NationsNo ratings yet

- Are Americans Worried About The NSA? AEI Political Report July/August 2013Document9 pagesAre Americans Worried About The NSA? AEI Political Report July/August 2013American Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Americans-and-Cyber-Security-finalDocument43 pagesAmericans-and-Cyber-Security-finalteyoto2620No ratings yet

- Researching Developing Countries: A Data Resource Guide for Social ScientistsFrom EverandResearching Developing Countries: A Data Resource Guide for Social ScientistsNo ratings yet

- Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your OwnFrom EverandHive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your OwnRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Project Part 1 - Needs AssessmentDocument2 pagesProject Part 1 - Needs Assessmentapi-584372385No ratings yet

- How Much Is Data Privacy Worth-A Preliminary Investigation-Winegar & Sunstein-2019Document17 pagesHow Much Is Data Privacy Worth-A Preliminary Investigation-Winegar & Sunstein-2019Manohar BhatNo ratings yet

- You: For Sale: Protecting Your Personal Data and Privacy OnlineFrom EverandYou: For Sale: Protecting Your Personal Data and Privacy OnlineNo ratings yet

- Americans' Complicated Feelings About Social Media in An Era of Privacy ConcernsDocument5 pagesAmericans' Complicated Feelings About Social Media in An Era of Privacy ConcernsPhương HàNo ratings yet

- Americans' Mixed Feelings on Social Media PrivacyDocument5 pagesAmericans' Mixed Feelings on Social Media PrivacyPhương HàNo ratings yet

- Public Opinion and MeasurementDocument5 pagesPublic Opinion and MeasurementGISELLE GUERRANo ratings yet

- Summary of Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really AreFrom EverandSummary of Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really AreNo ratings yet

- Your Life, Your Way: An Introduction to the Foundation Forty LifestyleFrom EverandYour Life, Your Way: An Introduction to the Foundation Forty LifestyleNo ratings yet

- Summary of Recoding America by Jennifer Pahlka: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do BetterFrom EverandSummary of Recoding America by Jennifer Pahlka: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do BetterNo ratings yet

- The Truth About Lying: Why and How We All Do It and What to Do About ItFrom EverandThe Truth About Lying: Why and How We All Do It and What to Do About ItNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Treatment of Abused and Neglected Children and Their Families: It Takes a VillageFrom EverandMultidisciplinary Approaches to the Treatment of Abused and Neglected Children and Their Families: It Takes a VillageNo ratings yet

- Managing Privacy: Information Technology and Corporate AmericaFrom EverandManaging Privacy: Information Technology and Corporate AmericaNo ratings yet

- Collateral Damage: The Imperiled Status of Truth in American Public Discourse and Why It Matters to YouFrom EverandCollateral Damage: The Imperiled Status of Truth in American Public Discourse and Why It Matters to YouNo ratings yet

- Sense and Nonsense About SurveysDocument9 pagesSense and Nonsense About Surveysluiscebada6No ratings yet

- Transparent and Reproducible Social Science Research: How to Do Open ScienceFrom EverandTransparent and Reproducible Social Science Research: How to Do Open ScienceNo ratings yet

- DEMOCRATS versus REPUBLICANS: Research on the Behaviors of High School StudentsFrom EverandDEMOCRATS versus REPUBLICANS: Research on the Behaviors of High School StudentsNo ratings yet

- Committed to Availability, Conflicted about Morality: What the Millennial Generation Tells Us about the Future of the Abortion Debate and the Culture WarsFrom EverandCommitted to Availability, Conflicted about Morality: What the Millennial Generation Tells Us about the Future of the Abortion Debate and the Culture WarsNo ratings yet

- How Moral Philosophy Broke Politics: And How To Fix ItFrom EverandHow Moral Philosophy Broke Politics: And How To Fix ItRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Save Lives or Save the Rhetoric?: Comparing the Logic of Evidence with the Power of RhetoricFrom EverandSave Lives or Save the Rhetoric?: Comparing the Logic of Evidence with the Power of RhetoricNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse Pocket Atlas, Volume 4: Investigation, Documentation, and RadiologyFrom EverandChild Abuse Pocket Atlas, Volume 4: Investigation, Documentation, and RadiologyNo ratings yet

- Policy and Research on Gender Equality: An Overview: Gender Equality, #1From EverandPolicy and Research on Gender Equality: An Overview: Gender Equality, #1No ratings yet

- Common Core Affirmative - HSS 2015Document203 pagesCommon Core Affirmative - HSS 2015albert cardenasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Justice at the Crossroads: Transforming Crime and PunishmentFrom EverandCriminal Justice at the Crossroads: Transforming Crime and PunishmentNo ratings yet

- Why Government Fails So Often: And How It Can Do BetterFrom EverandWhy Government Fails So Often: And How It Can Do BetterRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Comparing The States 10th Edition - Fall 2019 - 06.10.19 PDFDocument326 pagesComparing The States 10th Edition - Fall 2019 - 06.10.19 PDFsammy alanNo ratings yet

- 3202 Genrx ReportDocument46 pages3202 Genrx Reportinesdmg02No ratings yet

- Article Review ExamplesDocument5 pagesArticle Review ExamplesMichael G. GenobiagonNo ratings yet

- Impact of Data Collection Methods on Responses to Sensitive QuestionsDocument30 pagesImpact of Data Collection Methods on Responses to Sensitive QuestionsLucasLuiselliNo ratings yet

- Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really AreFrom EverandEverybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (369)

- Summary of Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are | Conversation StartersFrom EverandSummary of Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are | Conversation StartersNo ratings yet

- Concept of Region - James and JonesDocument15 pagesConcept of Region - James and JonesNeha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Systems Around The WorldDocument3 pagesAgricultural Systems Around The WorldNeha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- CrimeDocument17 pagesCrimeNeha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Indus Water ConflictDocument7 pagesIndus Water ConflictNeha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Communal ConflictsDocument10 pagesCommunal ConflictsNeha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Microsystems Course Covers Sensors, DesignDocument11 pagesMicrosystems Course Covers Sensors, DesignRaviNo ratings yet

- BUSINESS TALE - A Story of Ethics, Choices, Success - and A Very Large Rabbit - Theme of Ethics Code or Code of Business Con - EditedDocument16 pagesBUSINESS TALE - A Story of Ethics, Choices, Success - and A Very Large Rabbit - Theme of Ethics Code or Code of Business Con - EditedBRIAN WAMBUINo ratings yet

- Lorenzo Tan National High School 2018-2019 Federated Parent Teacher Association Officers and Board of DirectorsDocument4 pagesLorenzo Tan National High School 2018-2019 Federated Parent Teacher Association Officers and Board of DirectorsWilliam Vincent SoriaNo ratings yet

- How To Recover An XP Encrypted FileDocument2 pagesHow To Recover An XP Encrypted FileratnajitorgNo ratings yet

- A Teacher Education ModelDocument128 pagesA Teacher Education ModelMelinda LabianoNo ratings yet

- Kneehab XP Instructions and UsageDocument16 pagesKneehab XP Instructions and UsageMVP Marketing and DesignNo ratings yet

- Connect Debug LogDocument20 pagesConnect Debug LogrohanZorba100% (1)

- Subhra Ranjan IR Updated Notes @upscmaterials PDFDocument216 pagesSubhra Ranjan IR Updated Notes @upscmaterials PDFSachin SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Digest Office of The Ombudsman V Samaniego 2008Document3 pagesDigest Office of The Ombudsman V Samaniego 2008Lea Gabrielle FariolaNo ratings yet

- Cis Bin Haider GRP LTD - HSBC BankDocument5 pagesCis Bin Haider GRP LTD - HSBC BankEllerNo ratings yet

- Product Data Sheet: Standard Auxiliary Contact, Circuit Breaker Status OF/SD/SDE/SDV, 1 Changeover Contact TypeDocument2 pagesProduct Data Sheet: Standard Auxiliary Contact, Circuit Breaker Status OF/SD/SDE/SDV, 1 Changeover Contact TypeChaima Ben AliNo ratings yet

- Federal Ombudsmen Institutional Reforms Act, 2013Document8 pagesFederal Ombudsmen Institutional Reforms Act, 2013Adv HmasNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - Exercise Lab - Mini-2Document3 pagesKami Export - Exercise Lab - Mini-2Ryan FungNo ratings yet

- Detection of Malicious Web Contents Using Machine and Deep Learning ApproachesDocument6 pagesDetection of Malicious Web Contents Using Machine and Deep Learning ApproachesInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Materials Storage and BuildingDocument3 pagesMaterials Storage and BuildingAmit GoyalNo ratings yet

- Water Supply Improvement SchemeDocument110 pagesWater Supply Improvement SchemeLeilani JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Lab Exercise 3 SoilScie Group4Document10 pagesLab Exercise 3 SoilScie Group4Jhunard Christian O. AsayasNo ratings yet

- Bomani Barton vs. Kyu An and City of Austin For Alleged Excessive Use of ForceDocument16 pagesBomani Barton vs. Kyu An and City of Austin For Alleged Excessive Use of ForceAnonymous Pb39klJNo ratings yet

- Organisation Structure and Management RolesDocument26 pagesOrganisation Structure and Management RolesFiona TauroNo ratings yet

- Minhaj University Lahore: Paper: ICT BSCS Smester-1 Section C Instructor: Kainat Ilyas Exam: Mid-Term Total Marks: 25Document4 pagesMinhaj University Lahore: Paper: ICT BSCS Smester-1 Section C Instructor: Kainat Ilyas Exam: Mid-Term Total Marks: 25Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- 2015 Idmp Employee Intentions Final PDFDocument19 pages2015 Idmp Employee Intentions Final PDFAstridNo ratings yet

- Andrija Kacic Miosic - Razgovor Ugodni Naroda Slovinskoga (1862)Document472 pagesAndrija Kacic Miosic - Razgovor Ugodni Naroda Slovinskoga (1862)paravelloNo ratings yet

- TerrSet TutorialDocument470 pagesTerrSet TutorialMoises Gamaliel Lopez Arias100% (1)

- Penetron Admix FlyerDocument2 pagesPenetron Admix Flyernght7942No ratings yet

- 2DArtist Issue 019 Jul07 Lite PDFDocument53 pages2DArtist Issue 019 Jul07 Lite PDFViviane Hiromi Sampaio FurukawaNo ratings yet

- Communicate With S7-1200 Via EhernetDocument6 pagesCommunicate With S7-1200 Via EhernetRegisNo ratings yet

- Sjzl20061019-ZXC10 BSCB (V8.16) Hardware ManualDocument69 pagesSjzl20061019-ZXC10 BSCB (V8.16) Hardware ManualAhmadArwani88No ratings yet

- Comments PRAG FinalDocument13 pagesComments PRAG FinalcristiancaluianNo ratings yet

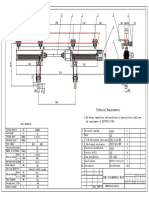

- 2X16-24 Monorail Hoist-04 - 2Document1 page2X16-24 Monorail Hoist-04 - 2RafifNo ratings yet

- MB1 - The Australian Economy PA 7092016Document8 pagesMB1 - The Australian Economy PA 7092016ninja980117No ratings yet

![On the Principles of Social Gravity [Revised edition]: How Human Systems Work, From the Family to the United Nations](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/506903532/149x198/a69b72a600/1638572554?v=1)