Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Internal Medicine Journal - 2020 - Gilmore - Cytomegalovirus in Inflammatory Bowel Disease A Clinical Approach

Uploaded by

Diego Fernando Ortiz TenorioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Internal Medicine Journal - 2020 - Gilmore - Cytomegalovirus in Inflammatory Bowel Disease A Clinical Approach

Uploaded by

Diego Fernando Ortiz TenorioCopyright:

Available Formats

doi:10.1111/imj.

15085

REVIEW

Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical

approach

Robert B. Gilmore,1,2 Kirstin M. Taylor,1,3 C. Orla Morrissey3,4 and Bradley J. Gardiner 3,4

Departments of 1Gastroenterology, and 4Infectious Disease, Alfred Health, 2Department of Gastroenterology, Austin Health, and 3Central Clinical

School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Key words Abstract

inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis,

cytomegalovirus. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection can be a challenging clinical problem in patients with

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly ulcerative colitis. Clinical presentation is

Correspondence difficult to distinguish from an underlying disease flare. Several diagnostic modalities

Bradley J. Gardiner, Department of Infectious are now available and when combined can aid clinicians in the identification of patients

Diseases, Alfred Health, 55 Commercial Road, who are most likely to benefit from antiviral therapy. The aim of this article is to review

Melbourne, Vic. 3004, Australia. the available literature and outline a practical approach to the diagnosis and manage-

Email: bradgardiner@gmail.com ment of CMV in patients with IBD.

Received 21 July 2020; accepted

27 September 2020.

Introduction

Reactivation of latent cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection immune activity is required to inhibit viral replication

is increasingly recognised as an important clinical prob- and prevent reactivation. With immunosuppression,

lem in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), CMV reactivation can occur and lead to a spectrum of

particularly among those with acute severe colitis receiv- clinical disease. It is estimated to affect 10–30% of

ing high doses of immunosuppression.1 Diagnosis can be patients with active IBD.4 The highest risk subgroup is

complicated given the multiple testing modalities avail- patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis (UC),

able, and identifying which patients are most likely to although it can also affect those with Crohn disease.5

benefit from antiviral therapy can be challenging. The Acute (primary) CMV infection in previously seronega-

aim of this article is to review the relevant literature and tive individuals can also occur, resulting in significant

propose an updated practical clinical approach to these clinical illness.

difficult cases. Several studies have explored risk factors for CMV

reactivation in patients with IBD. In one large meta-anal-

ysis, glucocorticoids (odds ratio (OR) 2.05; 95% confi-

Epidemiology dence interval (CI) 1.40–2.99) and thiopurines (OR 1.56;

CMV is a ubiquitous herpesvirus with a seroprevalence 95% CI 1.01–2.39) were associated with CMV reac-

in Australia around 75%, increasing with age.2 Infection tivation, but not tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α antago-

is frequently acquired in childhood or adolescence via nists such as infliximab (OR 1.44; 95% CI 0.93–2.24).6

exposure to blood or body fluids and is typically mini- There is emerging evidence to suggest that patients

mally symptomatic.3 Viral DNA integrates into the host receiving the gut-selective integrin inhibitor vedolizumab

and persists, resulting in life-long latency. Ongoing are also at higher risk of developing CMV disease com-

pared with those receiving infliximab (hazard ratio 2.3;

95% CI 0.5–9.3).7 While the role of CMV as a pathogen

Funding: B. J. Gardiner is supported by the National Health and

versus bystander has been long debated, it is increasingly

Medical Research Council of Australia (grant number

GNT1150351). apparent that CMV colitis can result in significant mor-

Conflict of interest: None. bidity and mortality in patients with IBD, and contributes

Internal Medicine Journal 52 (2022) 365–368 365

© 2020 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

14455994, 2022, 3, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/imj.15085 by Cochrane Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [15/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

Gilmore et al.

to increased risk of hospitalisation and colectomy.5,8,9 the relative contribution of CMV to a patient’s presenta-

Antiviral treatment can lead to clinical improvement in tion, in general the higher the burden of CMV seen on

IBD patients with CMV, facilitating ongoing immuno- microscopic examination of the colon, the more likely

modulatory therapy and sustained remission that antiviral treatment will be helpful in achieving reso-

afterwards.10 lution of colitis. The presence of >5 IHC positive cells per

2 mm tissue is significantly higher in patients with

steroid-refractory disease.14 Patients with >10 IHC posi-

Clinical features

tive cells per section, have an increased risk of cole-

In patients with IBD, CMV typically presents as colitis ctomy.15 Tissue PCR is increasingly used and can detect

with or without systemic features such as fever, malaise very small amounts of CMV present in tissue, which may

and leukopenia. CMV can also cause a diverse variety of at times be of questionable clinical significance.13 Sensitiv-

syndromes best described in transplant recipients includ- ity is higher on fresh tissue, although many laboratories

ing pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis and a non-specific are able to perform it on formalin-fixed paraffin-

febrile illness termed ‘CMV syndrome’. While not com- embedded samples. Higher tissue viral loads may be more

monly seen in patients with IBD, symptoms apart from significant but have not been well validated and quantita-

colitis are possible. Although CMV disease occurs most tive testing of biopsy samples is not routinely available.10

commonly in those with acute severe or chronically While stool CMV PCR is appealing due to the ease of sam-

active UC, and in particular steroid-refractory disease, it ple collection, this test is not currently recommended out-

should be considered in all patients with acute colitis, side of a research setting as the sensitivity and specificity

due to the inability to distinguish clinically or endoscopi- are not well established.16

cally from an idiopathic disease flare. A recent meta- A suggested approach to evaluating IBD patients with

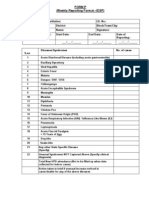

analysis has concluded that patients with acute severe suspected CMV colitis is shown in Figure 1.

colitis and concurrent CMV are more likely to have

steroid-refractory disease, with an increase in steroid

Management

resistance from 30% in the CMV-negative group to 52%

in the CMV positive group (OR 3.63; 95% CI 1.99–6.62; Identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from

P < 0.0001).11 antiviral therapy can be challenging; however, it is clear

that treatment is of most benefit in patients with a high

burden of CMV who have received corticosteroids with-

Diagnosis

out clinical improvement. Antiviral therapy has been

There are several diagnostic modalities available to detect associated with reduced need for colectomy in this sub-

CMV, each with their own advantages and limitations. group.5 In patients with a low burden of CMV identified

These tests must be used in combination when evaluat- on diagnostic testing (e.g. isolated positive tissue PCR or

ing a suspected case for optimal results. Serology is a low-level viraemia), antiviral treatment can be deferred

simple, highly sensitive, inexpensive and readily avail- while awaiting a response to empiric corticosteroids.17

able way to confirm prior exposure to CMV or evaluate Two studies looking at patients with active UC and CMV

for acute infection. Negative serology can preclude the infection diagnosed on positive serum PCR alone found

need for further investigation for CMV if obtained no differences in length of hospital stay, rate of relapse,

promptly. Quantitative serum viral load (polymerase colectomy rates or mortality compared to CMV negative

chain reaction (PCR)) testing is now widespread and able patients.18,19 If salvage therapy is used, the case for CMV

to detect very low levels of CMV. While high viral loads treatment becomes stronger as increased immunosup-

are more likely to indicate severe disease in a more pression can lead to further CMV reactivation. Once a

heavily immunosuppressed patient, the absence of vir- diagnosis of CMV colitis is made, priority should be given

aemia does not rule out CMV colitis. to weaning corticosteroids while using another agent to

Histopathologic evaluation of tissue specimens remains reduce inflammation and induce remission. Infliximab is

the gold-standard diagnostic investigation. Early flexible preferred over ciclosporin where possible due to the

sigmoidoscopy is recommended, targeting inflamed areas potential TNF-avidity of CMV.20 Thiopurines should be

for biopsy, with more biopsies increasing the diagnostic ceased, at least temporarily. A randomised controlled

yield. Sampling error is minimised with 11–16 biopsies trial is underway to determine the optimal strategy for

but this number can be difficult to obtain routinely.12,13 patients receiving vedolizumab.21

The presence of viral inclusions is highly specific for CMV The mainstay of antiviral therapy is intravenous ganci-

and sensitivity is increased with immunohistochemical clovir and its oral equivalent valganciclovir. Patients

(IHC) staining.9,12 While it can be difficult to determine should be initiated on intravenous therapy, then

366 Internal Medicine Journal 52 (2022) 365–368

© 2020 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

14455994, 2022, 3, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/imj.15085 by Cochrane Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [15/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

Cytomegalovirus infection in IBD

Figure 1 An approach to the clinical evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease patients with suspected cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis. †Biopsies sent

both fresh for CMV tissue polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and in formalin for histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical staining.

switched to valganciclovir once improving and reliably extremely challenging to manage in some cases, requir-

absorbing oral medications. Myelosuppression is the ing alternative agents such as foscarnet and cidofovir

most common serious adverse event. Patients require which have problematic side effect profiles.24 Guidelines

weekly monitoring with full blood count and G-CSF sup- have not traditionally recommended routine CMV sero-

port is occasionally required. Optimising antiviral dosing logical screening in patients with IBD, but this could be

is crucial, particularly in patients with renal dysfunction, considered at baseline to inform of risk of reactivation

as dose reduction is required but underdosing can and facilitate rapid diagnostic evaluation during the pre-

increase the risk of treatment failure and subsequent sentation of a flare.22,23,25

resistance.22

The overall duration of treatment should be individua-

Conclusion

lised and guided by the clinical and virologic response.

The minimum recommended duration is 2 weeks but can CMV infection is an increasingly common clinical prob-

extend to 6 or more if required. If the viral load is detect- lem in patients with IBD and is associated with adverse

able at initial diagnosis, serum PCR can be performed outcomes. Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and

weekly to guide ongoing therapy beyond the resolution effective treatment strategies, selecting which patients

of viraemia. In patients without viraemia, assessing will benefit from antiviral therapy remains challenging.

response can be more challenging and is generally guided A growing body of evidence suggests that patients most

by symptomatic improvement in diarrhoea.22,23 Repeat likely to benefit are those with steroid-refractory colitis,

endoscopic evaluation may be required if symptoms fail particularly where serum viral loads are high or multiple

to improve. inclusions are seen on histology. A collaborative

While antiviral prophylaxis is used routinely in trans- approach to management involving gastroenterologists,

plant recipients, there is little evidence to guide primary infectious diseases physicians and colorectal surgeons is

or secondary prophylaxis in patients with IBD. Recur- recommended to ensure optimal outcomes for these

rent, refractory and resistant CMV can occur and can be complex patients.

Internal Medicine Journal 52 (2022) 365–368 367

© 2020 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

14455994, 2022, 3, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/imj.15085 by Cochrane Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [15/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

Gilmore et al.

References with worse outcomes in inflammatory 17 Travis S, Farrant J, Ricketts C, Nolan D,

bowel disease hospitalizations Mortensen N, Kettlewell M et al.

1 Park SC, Jeen YM, Jeen YT. Approach nationwide. Int J Colorectal Dis 2020; 35: Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative

to cytomegalovirus infections in patients 897–903. colitis. Gut 1996; 38: 905–10.

with ulcerative colitis. Korean J Intern 10 Roblin X, Pillet S, Oussalah A, 18 Delvincourt M, Lopez A, Pillet S,

Med 2017; 32: 383–92. Berthelot P, Del Tedesco E, Phelip JM Bourrier A, Seksik P, Cosnes J et al. The

2 Lancini DV, Faddy HM, Ismay S, et al. Cytomegalovirus load in inflamed impact of cytomegalovirus reactivation

Chesneau S, Hogan C, Flower RL. intestinal tissue is predictive of and its treatment on the course of

Cytomegalovirus in Australian blood resistance to immunosuppressive inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment

donors: seroepidemiology and therapy in ulcerative colitis. Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 712–20.

seronegative red blood cell component Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 19 Matsuoka K, Iwao Y, Mori T,

inventories. Transfusion 2016; 56: 2001–8. Sakuraba A, Yajima T, Hisamatsu T et al.

1616–21. 11 Lv YL, Han FF, Jia YJ, Wan ZR, Cytomegalovirus is frequently

3 Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, Gong LL, Liu H et al. Is cytomegalovirus reactivated and disappears without

Josephson F, Lundgren J, Nichols G infection related to inflammatory bowel antiviral antigens in ulcerative colitis

et al. Definitions of cytomegalovirus disease, especially steroid-resistant patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:

infection and disease in transplant inflammatory bowel disease? A meta- 331–7.

patients for use in clinical trials. Clin analysis. Infect Drug Resist 2017; 10: 20 Criscuoli V, Mocciaro F, Orlando A,

Infect Dis 2017; 64: 87–91. 511–9. Rizzuto MR, Renda MC, Cottone M.

4 Sager K, Alam S, Bond A, 12 Mills AM, Guo FP, Copland AP, Pai RK, Cytomegalovirus disappearance after

Chinnappan L, Probert CS. Review Pinsky BA. A comparison of CMV treatment for refractory ulcerative

article: cytomegalovirus and detection in gastrointestinal mucosal colitis in 2 patients treated with

inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment biopsies using immunohistochemistry infliximab and 1 patient with

Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 725–33. and PCR performed on formalin-fixed, leukapheresis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;

5 Shukla T, Singh S, Loftus EV Jr, paraffin-embedded tissue. Am J Surg 15: 810–1.

Bruining DH, McCurdy JD. Antiviral Pathol 2013; 37: 995–1000. 21 Impact of Anti-cytomegalovirus

therapy in steroid-refractory ulcerative 13 Kim JJ, Simpson N, Klipfel N, Debose R, (Valganciclovir) Treatment in the

colitis with cytomegalovirus: systematic Barr N, Laine L. Cytomegalovirus Management of Relapsing Ulcerative

review and meta-analysis. Inflamm infection in patients with active Colitis (UC) Requiring Vedolizumab

Bowel Dis 2015; 21: 2718–25. inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci Therapy. NCT04064697, ClinicalTrials.

6 Shukla T, Singh S, Tandon P, 2010; 55: 1059–65. gov. 2020.

McCurdy J. Corticosteroids and 14 Jung KH, Kim J, Lee HS, Choi J, 22 Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM,

thiopurines, but not tumor necrosis Jang SJ, Jung J et al. Clinical Huprikar S, Chou S, Danziger-Isakov L

factor antagonists, are associated with implications of the CMV-specific T-cell et al. The third international consensus

cytomegalovirus reactivation in response and local or systemic CMV guidelines on the management of

inflammatory bowel disease: a viral replication in patients with cytomegalovirus in solid-organ

systematic review and meta-analysis. moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. transplantation. Transplantation 2018;

J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51: 394–401. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6: ofz526. 102: 900–31.

7 Hommel C, Roblin X, Brichet L, Bihin B, 15 Kuwabara A, Okamoto H, Suda T, 23 Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C,

Pillet S, Rahier J-F. Risk of CMV Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y

reactivation in UC patients with previous Clinicopathologic characteristics of et al. Second European evidence-based

history of CMV infection following clinically relevant cytomeglovirus consensus on the prevention, diagnosis

infliximab or vedolizumab treatments. infection in inflammatory bowel and management of opportunistic

J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12: S400. disease. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42: 823–9. infections in inflammatory bowel

8 Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS, Jeong SY, 16 Prachasitthisak N, Tanpowpong P, disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8: 443–68.

Park SJ, Cheon JH et al. Long-term Lertudomphonwanit C, 24 Hakki M, Chou S. The biology of

outcomes of cytomegalovirus Treepongkaruna S, Boonsathorn S, cytomegalovirus drug resistance. Curr

reactivation in patients with moderate Angkathunyakul N et al. Short article: Opin Infect Dis 2011; 24: 605–11.

to severe ulcerative colitis: a multicenter stool cytomegalovirus polymerase chain 25 Fakhreddine AY, Frenette CT,

study. Gut Liver 2014; 8: 643–7. reaction for the diagnosis of Konijeti GG. A practical review of

9 Hendler S, Barber G, Okafor P, cytomegalovirus-related gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus in gastroenterology

Chang M, Limsui D, Limketkai B. disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; and hepatology. Gastroenterol Res Pract

Cytomegalovirus infection is associated 29: 1059–63. 2019; 2019: 6156581.

368 Internal Medicine Journal 52 (2022) 365–368

© 2020 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

You might also like

- Fast Facts: Complex Perianal Fistulas in Crohn's Disease: A multidisciplinary approach to a clinical challengeFrom EverandFast Facts: Complex Perianal Fistulas in Crohn's Disease: A multidisciplinary approach to a clinical challengeNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors of Cytomegalovirus Reactivation in UlcerativeDocument15 pagesRisk Factors of Cytomegalovirus Reactivation in UlcerativeNatalyFuertesNo ratings yet

- A Rose Is A Rose Is A Rose But CVID Is Not CVID - Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) What Do We Know in 2011Document61 pagesA Rose Is A Rose Is A Rose But CVID Is Not CVID - Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) What Do We Know in 2011vishnupgiNo ratings yet

- UEG Mistakes in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis and How To Avoid Them 2023Document3 pagesUEG Mistakes in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis and How To Avoid Them 2023Mohamad MostafaNo ratings yet

- Physical, Laboratory, Radiographic, and Endoscopic Workup For Clostridium Difficile ColitisDocument5 pagesPhysical, Laboratory, Radiographic, and Endoscopic Workup For Clostridium Difficile ColitisJoaquin Martinez HernandezNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1083879118313909Document2 pagesPi Is 1083879118313909Ljc JaslinNo ratings yet

- Biology of Blood and Marrow TransplantationDocument6 pagesBiology of Blood and Marrow TransplantationSeruni Allisa AslimNo ratings yet

- Ibd1156 PDFDocument8 pagesIbd1156 PDFPrakashNo ratings yet

- Nneoma Odoemena Preceptor Richard Williams February 23, 2018Document3 pagesNneoma Odoemena Preceptor Richard Williams February 23, 2018Nneoma OdoemenaNo ratings yet

- Em Article C DiffDocument6 pagesEm Article C Diffsgod34No ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus Infection and Disease in The New Era of Immunosuppression Following Solid Organ TransplantationDocument9 pagesCytomegalovirus Infection and Disease in The New Era of Immunosuppression Following Solid Organ TransplantationReza Firmansyah IINo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus: Cytomegalovirus, Also Known As Human Herpesvirus (HHV-5), CMV ORDocument9 pagesCytomegalovirus: Cytomegalovirus, Also Known As Human Herpesvirus (HHV-5), CMV ORQuenzil LumodNo ratings yet

- Cdi and FMT Risks and BenefitsDocument5 pagesCdi and FMT Risks and Benefitsapi-426734065No ratings yet

- CMVDocument24 pagesCMVecko Roman100% (1)

- Severe Systemic Cytomegalovirus Infection in An Immunocompetent Patient Outside The Intensive Care Unit: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesSevere Systemic Cytomegalovirus Infection in An Immunocompetent Patient Outside The Intensive Care Unit: A Case ReportSebastián Garay HuertasNo ratings yet

- Practice - Parameter - Clostridium - Difficile - InfectionDocument15 pagesPractice - Parameter - Clostridium - Difficile - InfectionIfeanyichukwu OgbonnayaNo ratings yet

- Celiac Disease and The Potential of Stems Cells As TreatmentDocument9 pagesCeliac Disease and The Potential of Stems Cells As TreatmentAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus in Primary ImmunodeficiencyDocument9 pagesCytomegalovirus in Primary ImmunodeficiencyAle Pushoa UlloaNo ratings yet

- Severe Cytomegalovirus Infection in Apparently Immunocompetent Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesSevere Cytomegalovirus Infection in Apparently Immunocompetent Patients: A Systematic ReviewSamanta CadenasNo ratings yet

- Citomegalovirus en PostranplantadosDocument26 pagesCitomegalovirus en PostranplantadosJC ChafloqueNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic-Associated ColitisDocument10 pagesAntibiotic-Associated ColitisHendraGusmawanNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 2106516Document10 pagesNej Mo A 2106516ItaloNo ratings yet

- Clostridium y MicrobiomaDocument10 pagesClostridium y MicrobiomaSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Cis 551Document8 pagesCis 551Lina Mahayaty SembiringNo ratings yet

- Clostridium Difficile-Associated Diarrhea in The Oncology PatientDocument7 pagesClostridium Difficile-Associated Diarrhea in The Oncology PatientK. O.No ratings yet

- Clinical Diagnostic Testing For Human CytomegalovirusDocument12 pagesClinical Diagnostic Testing For Human Cytomegalovirusdossantoselaine212No ratings yet

- Ca Colon 2Document19 pagesCa Colon 2Tob JurNo ratings yet

- ACG Guideline Cdifficile April 2013Document21 pagesACG Guideline Cdifficile April 2013Fitria FieraNo ratings yet

- Invasivecandidiasis: Todd P. Mccarty,, Peter G. PappasDocument22 pagesInvasivecandidiasis: Todd P. Mccarty,, Peter G. PappasAnonymous By8a7sArRNo ratings yet

- Mistakes in Series 06 2021 Colitis SurveillanceDocument3 pagesMistakes in Series 06 2021 Colitis SurveillanceFaisal BaigNo ratings yet

- State-Of-The-Art Diagnostic Evaluation of Common Variable ImmunodeficiencyDocument9 pagesState-Of-The-Art Diagnostic Evaluation of Common Variable ImmunodeficiencyGreen LightNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Diagnosis of CMV Infection: A ReviewDocument6 pagesLaboratory Diagnosis of CMV Infection: A ReviewAchmad ArrizalNo ratings yet

- Transplantation and Cellular TherapyDocument8 pagesTransplantation and Cellular TherapyAnak MuadzNo ratings yet

- MKSAP 16 - Infectious DiseaseDocument340 pagesMKSAP 16 - Infectious DiseaseBacanator75% (4)

- Clostridioides Difficile Infection in Patients WitDocument10 pagesClostridioides Difficile Infection in Patients WitElena Cuiban100% (1)

- RCUH Ghid 2010Document23 pagesRCUH Ghid 2010Georgiana CrisuNo ratings yet

- Cadazolid: A New Hope in The Treatment of Clostridium Difficile InfectionDocument10 pagesCadazolid: A New Hope in The Treatment of Clostridium Difficile InfectionMaria KNo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) HepatitisDocument3 pagesCytomegalovirus (CMV) HepatitisN NwekeNo ratings yet

- GLILD Mimicking Sarcoidosis 2021Document11 pagesGLILD Mimicking Sarcoidosis 2021Edoardo CavigliNo ratings yet

- 2022 Blood HIT Profilaxis Antimicrobiana Neoplasias LinfoidesDocument12 pages2022 Blood HIT Profilaxis Antimicrobiana Neoplasias LinfoidesMaria GarciaNo ratings yet

- Cvid Lancet 2008Document14 pagesCvid Lancet 2008Andre GarciaNo ratings yet

- Ulcerative Colitis: An Update: Authors: Jonathan P SegalDocument5 pagesUlcerative Colitis: An Update: Authors: Jonathan P SegalManoel Victor Moreira MachadoNo ratings yet

- Crohn 1 EspDocument8 pagesCrohn 1 EspRomina GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Pseudomembranouse ColitisDocument37 pagesPseudomembranouse ColitisFitria FieraNo ratings yet

- Fecal TransplantationDocument26 pagesFecal TransplantationjamalNo ratings yet

- Clostridioides No IdosoDocument14 pagesClostridioides No IdosoSCIH HFCPNo ratings yet

- An Updated Review of Clostridium Difficile Treatment in PediatricsDocument9 pagesAn Updated Review of Clostridium Difficile Treatment in PediatricsKhadijah Rizky SumitroNo ratings yet

- Nanoparticle-Mediated-Therapeutic-Approach-for-Ulcerative-Colitis-TreatmentDocument22 pagesNanoparticle-Mediated-Therapeutic-Approach-for-Ulcerative-Colitis-TreatmentAchudan JiiNo ratings yet

- RMV 2034Document6 pagesRMV 2034Ga HernandezNo ratings yet

- C Diff PDFDocument6 pagesC Diff PDFBobNo ratings yet

- Vaccination For Inflammatory Bowel Disease PatientsDocument10 pagesVaccination For Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patientsmusyawarah melalaNo ratings yet

- Herpesvirus Infections in Immunocompromised Patients: An OverviewDocument29 pagesHerpesvirus Infections in Immunocompromised Patients: An OverviewAyioKunNo ratings yet

- Opportunistic InfectionsDocument15 pagesOpportunistic InfectionsHimanshu MehtaNo ratings yet

- Wa0006.Document12 pagesWa0006.Jose VillasmilNo ratings yet

- CMV A Troll in ICUDocument11 pagesCMV A Troll in ICUMajd ShakerNo ratings yet

- Autoimmunity in Common Variable ImmunodeficiencyDocument11 pagesAutoimmunity in Common Variable ImmunodeficiencyAldito GlasgowNo ratings yet

- Clostridium Difficile ColitisDocument33 pagesClostridium Difficile ColitisLaura Anghel-MocanuNo ratings yet

- Toxic Megacolon: Daniel M. Autenrieth, MD, and Daniel C. Baumgart, MD, PHDDocument8 pagesToxic Megacolon: Daniel M. Autenrieth, MD, and Daniel C. Baumgart, MD, PHDGoran TomićNo ratings yet

- Hal1-R 2Document15 pagesHal1-R 2ronianandaperwira_haNo ratings yet

- Extrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent PersonsDocument9 pagesExtrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent Personsrajesh Kumar dixitNo ratings yet

- Catatonia Revived. A Unique Syndrome UpdatedDocument10 pagesCatatonia Revived. A Unique Syndrome UpdatedElisa PavezNo ratings yet

- Anti Psychotic DrugsDocument6 pagesAnti Psychotic DrugsJoseph NyirongoNo ratings yet

- CROSSWORD PUZZLE - Health ProblemsDocument4 pagesCROSSWORD PUZZLE - Health ProblemsVeZ xNo ratings yet

- Ward DrugsDocument5 pagesWard DrugsMary Grace AgataNo ratings yet

- Image Production & Evaluation - HandoutDocument30 pagesImage Production & Evaluation - HandoutKarl Jay-Ronn GubocNo ratings yet

- Levels of Neonatal CareDocument3 pagesLevels of Neonatal CareDelphy Varghese100% (11)

- Geron QuestionsDocument10 pagesGeron QuestionsTrisha ArizalaNo ratings yet

- Free Water ProtocolDocument42 pagesFree Water ProtocolMabel Uribe CerdaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Common Nail Disorders - YostDocument94 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Common Nail Disorders - Yosthaytham aliNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis MergedDocument73 pagesOsteoporosis MergedrlpmanglicmotNo ratings yet

- Respiratory System CaseDocument7 pagesRespiratory System CaseKanwaljeet SinghNo ratings yet

- IPC Vol1 Refernce Manual LaunchedDocument410 pagesIPC Vol1 Refernce Manual LaunchedAlwan YusufNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Diagnosis of Ascites of Undetermined Origin in A Developing Country: A Prospective StudyDocument9 pagesEtiology and Diagnosis of Ascites of Undetermined Origin in A Developing Country: A Prospective StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Bab3Document24 pagesBab3Setiawan Prayudha Wilyadana EndhangNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyDocument3 pagesEndoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyLoNo ratings yet

- About LevofloxacinDocument48 pagesAbout LevofloxacinMuhammad Ali Syahrun MubarokNo ratings yet

- NCM 118 Critical Thinking Exercises No. 1Document2 pagesNCM 118 Critical Thinking Exercises No. 1Trisha SuazoNo ratings yet

- We Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDocument22 pagesWe Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsKriti KumariNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine ActionDocument9 pagesAbnormal Uterine ActionAnu ThomasNo ratings yet

- Nejmra 2207410Document15 pagesNejmra 2207410rindayusticia100% (1)

- Adhesive CapsulitisDocument25 pagesAdhesive CapsulitisHari PrasadNo ratings yet

- Tutorial PathologyDocument4 pagesTutorial PathologyNURIN INSYIRAH MOHD ZAMRINo ratings yet

- Reflection-Personal HygieneDocument2 pagesReflection-Personal HygienePang ChixxNo ratings yet

- IDSP P&L FormsDocument2 pagesIDSP P&L FormsKunal YadavNo ratings yet

- Surface Disinfection With Chlorine (Bleach)Document2 pagesSurface Disinfection With Chlorine (Bleach)cabeaureyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines in Neonatology 1st EditionDocument958 pagesClinical Guidelines in Neonatology 1st EditionGaby Rivera0% (1)

- A Manual: For Estimating Disease Burden Associated With Seasonal InfluenzaDocument128 pagesA Manual: For Estimating Disease Burden Associated With Seasonal InfluenzaAlina DrucNo ratings yet

- Vpe 311 TanuvasDocument281 pagesVpe 311 Tanuvaskaran kambojNo ratings yet

- Drug-Induced Sleepiness and Insomnia: An Update: Sonolência e Insônia Causadas Por Drogas: Artigo de AtualizaçãoDocument8 pagesDrug-Induced Sleepiness and Insomnia: An Update: Sonolência e Insônia Causadas Por Drogas: Artigo de AtualizaçãoRene FernandesNo ratings yet

- Caldas Et Al. (2021)Document13 pagesCaldas Et Al. (2021)Kesley PabloNo ratings yet