Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Owl House (Museum)

The Owl House (Museum)

Uploaded by

Adreno CortexOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Owl House (Museum)

The Owl House (Museum)

Uploaded by

Adreno CortexCopyright:

Available Formats

Search Wikipedia Search Create account Log in

The Owl House (museum) 2 languages

Contents [hide] Article Talk Read Edit View history Tools

(Top) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 31°52′3″S 24°33′10″E

Helen Martins

The Owl House is a museum in Nieu-Bethesda, Eastern Cape, South Africa. The owner, Helen Martins,

Construction The Owl House

turned her house and the area around it into a visionary environment, elaborately decorated with ground

Death

glass and containing more than 300 concrete sculptures including owls, camels, peacocks, pyramids, and

Museum people. She inherited the house from her parents and began its transformation after they died.[1]

In popular culture

Gallery Helen Martins [ edit ]

References Helen Martins was a reclusive outsider artist[2] who remains something of an enigma.[3] Born on 23

December 1897 in Nieu-Bethesda, she was the youngest of six surviving children of Pieter Jakobus

Further reading

Martins and Hester Catharina Cornelia van der Merwe.[4][5]

External links

Helen was schooled in Graaf-Reinet and obtained a teaching diploma at the teachers college in Graaf-

Reinet (now the police training college).[5]

In 1919, Helen Martins moved to the Transvaal where she began teaching. On 7 January 1920, she

married a colleague by the name of Willem Johannes Pienaar.[6][7] The couple travelled around the

country acting in theatre productions in the Transvaal, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. Their marriage was

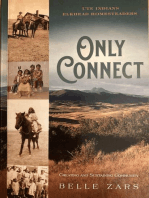

A large arch with an owl at the peak.

not a happy one, and Helen left her husband on several occasions. She eventually divorced Pienaar in

1926.[6][7]

Some time around 1927 or 1928, Helen returned to Nieu-Bethesda where she stayed for the next 31

years taking care of her elderly parents. Her mother Hester, with whom she reportedly had a close

relationship, died of breast cancer in 1941.[6][7] Her father has been various described as "eccentric and

demanding"[4] and possibly abusive.[6] He lived in an outside room, with a stove and a bed to sleep on.

After her father died of stomach cancer in 1945,[6] Helen bricked up the windows, painted his room black,

and put a sign reading "The Lion's Den".[8]

When Martins was about 60, she married Mr. J.J.M. Niemand, a pensioner and furniture restorer in the Wikimedia | © OpenStreetMap

village. The marriage lasted only three months.[4] Location Nieu-Bethesda, Eastern Cape,

South Africa

Construction [ edit ] Website owlhouse.org.za

Her parents left Helen the house. After their deaths Martins started to transform the house and the

Helen Martins

garden, spending years creating a visionary environment.[9][5]

She is believed to have begun within the house, employing locals Jonas Adams and Piet van der Merwe

to make structural alterations, and covering interior surfaces with ground glass. Windows, mirrors and

lights further enhanced the illumination inside.[1][10] Martins also used cement and wire, decorating the

interior of her home and later building sculptures in her garden.[11][12] Her partner and lover Johannes

Hattingh constructed the first cement animals and build much of the early Owl House bestiary.[8] In 1964,

she was joined in her work by Koos Malgas, who helped her build the sculptures in the outside area

called the Camel Yard.[13] Theirs was an intensely collaborative process, meeting daily to envisioning and

create new works.[14]

Martins was inspired by Christian biblical texts, the poetry of Omar Khayyam, and various works by

William Blake.[11] The Camel Yard contains more than 300 sculptures, many of owls, camels, and people.

Most are oriented toward the east as a tribute to Martins' fascination with Mecca and the Orient. A sign in Born December 23, 1897

Nieu-Bethesda, Eastern Cape,

the yard says "This is My World."[1]

South Africa

There are suggestions that their neighbours may have been suspicious of the relationship between Died August 8, 1976

[15]

Malgas, a coloured man, and Martins, a white woman. There are also suggestions that Martins got Known for The Owl House

along better with her coloured neighbours (to whom she reportedly sold illegally brewed alcohol) than with

members of the austere Dutch Reformed Church.[6][7] Nonetheless, although she was somewhat reclusive (and External video

became increasingly so as she grew older), Helen Martins invited her neighbours to view her house when

decorated for Christmas.[15] There are also indications that her neighbours helped to care for Helen's father in

his last years, and that they gave her food when she did not care for herself.[6] Relationships between her and

the community she lived in were clearly complicated and often difficult.[6]

Death [ edit ]

Martin's longtime exposure to the fine crushed glass she used to decorate her walls and ceilings eventually “Helen Martin's Owl House – Nieu

caused her eyesight to start failing. This led her to attempt suicide by ingesting caustic soda on 6 August 1976 Bethesda” , Adrienne Allderman

at the age of 78.[8][6][16] She was found and taken to a hospital in Graaff-Reinet, where she died on 8 August

1976.[17]

Museum [ edit ]

As per her wishes,[5] the Owl House has been kept intact as a museum. In 1991, the Friends of The Owl House arranged for Koos Malgas to return to

Nieu-Bethesda to care for the site. The Owl House Foundation, which was formed in 1996, now manages the site.[1] The house was declared a

provincial heritage site in 1989[4] and was opened as a museum in 1992.[18]

In popular culture [ edit ]

Athol Fugard published a play based on Helen Martins[19] in 1985 called The Road to Mecca, which was later made into a film of the same name. In

2015, a Marathi play Prawaas was produced by Abbhivyaktee theatre group from Panaji (Goa). Written and directed by Saish Deshpande, the play was

influenced by Martin's story and Athol Fugard's play.

Gallery [ edit ]

One of the interior rooms Sculptures in the garden, Close-up of one of the

with crushed glass on most are facing east. sculptures.

the walls.

References [ edit ]

1. ^ a b c d "The Owl House, Nieu-Bethesda, South Africa" . PBS 11. ^ a b Pinchuck, Tony; Heuler, Hilary; Marle, Jeroen van; Mouritsen, Lone

Independent Lens. Retrieved 11 March 2016. (2012). The rough guide to South Africa, Lesotho & Swaziland. London:

2. ^ "Helen Martins" . Outsider Art Now. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 11 March Rough Guides. p. 394. ISBN 978-1405386500.

2016. 12. ^ Collins, Niki (1 June 1986). "South African Gaudi: Helen Martins" .

3. ^ Marsh, Rob (1994). Unsolved mysteries of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Women Artists News: 28. ISSN 0149-7081 . Retrieved 4 March 2016.

Struik. ISBN 9781868254064. 13. ^ McLean, Ian (2014). Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous

4. ^ a b c d Verwey, E. J. (1995). New dictionary of South African biography Contemporary Art. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 265.

(1st ed.). Pretoria: HSRC Publishers. pp. 160–162. ISBN 9780796916488. ISBN 9781443867436.

5. ^ a b c d "Helen Elizabeth Martins" . South African History Online. 14. ^ Malgas, Julia; Couzyn, Jeni (2008). Koos Malgas, sculptor of the Owl

Retrieved 11 March 2016. House. Nieu Bethesda: Firelizard. ISBN 9780953505821.

6. ^ a b c d e f g h i Ross, Sue Imrie (1997). This is my world : the life of Helen 15. ^ a b "Outsider Art, Outsider Artists : South Africa's Queen of Outsider Art,

Martins, creator of the Owl House. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. Helen Martins" . Art and Design Inspiration. 15 December 2013.

ISBN 978-0195715163. 16. ^ Smiedt, David (2004). Are we there yet : chasing a childhood through

7. ^ a b c d "The Extraordinary Life of Helen Martins" . lynnssite. February South Africa. St. Lucia, Qld.: University of Queensland Press. p. 289.

2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015. ISBN 978-0702233845.

8. ^ a b c Emslie, Anne (1997). A journey through the Owl House. 17. ^ "Helen Martins – The owlhouse" . theowlhouse.co.za. Retrieved

Johannesburg: Penguin Books. p. 3. ISBN 9780140255560. 4 March 2016.

9. ^ "Other Visionary Art Environments" . Philadelphia Magic Garden. 18. ^ Plessis, Heather du (2000). Tourism destinations southern Africa.

Retrieved 11 March 2016. [Kenwyn, South Africa]: Juta. p. 152. ISBN 9780702152726.

10. ^ "The Owl House – The owlhouse" . theowlhouse.co.za. Retrieved 19. ^ "The Owl House of Nieu-Bethesda" . Encounter South Africa. Retrieved

4 March 2016. 11 March 2016.

Further reading [ edit ]

Gotthardt, Alexxa (June 13, 2018). "The South African Teacher Who Turned Her Home into a Sanctuary of Color and Light" . Artsy. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

Lyster, Rosa (February 1, 2018). "A Visit to South Africa's Strange, Astonishing Owl House" . The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X .

External links [ edit ]

Official website Wikimedia Commons has

Site by The Owl House , at SAHRA media related to Owl House.

Categories: Visionary environments Monuments and memorials in South Africa Museums in the Eastern Cape Karoo

Art museums and galleries in South Africa Outsider artists Women outsider artists

This page was last edited on 10 April 2023, at 10:17 (UTC).

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Code of Conduct Mobile view Developers Statistics Cookie statement

You might also like

- The Demarest FamilyDocument1,323 pagesThe Demarest FamilyStephen Miller100% (7)

- Art 2 Unit 5Document8 pagesArt 2 Unit 5api-264152935100% (4)

- The Art Deco Mansion in St Lucia: What drove the man who built it?From EverandThe Art Deco Mansion in St Lucia: What drove the man who built it?No ratings yet

- Modern ArchitectureDocument45 pagesModern ArchitectureShrishank Rudra100% (1)

- The New Yorker - September 19.2016Document97 pagesThe New Yorker - September 19.2016Rosmirella Cano100% (1)

- Fakes and Forgeries PDFDocument2 pagesFakes and Forgeries PDFTracyNo ratings yet

- Visionary Environment Helen Martins and The Owl House of Nieu Bethesda 02Document6 pagesVisionary Environment Helen Martins and The Owl House of Nieu Bethesda 02Tony McGregorNo ratings yet

- The Outback Songman Chapter SamplerDocument22 pagesThe Outback Songman Chapter SamplerAllen & UnwinNo ratings yet

- 21CLPW - Lesson 5Document2 pages21CLPW - Lesson 5des oroNo ratings yet

- The House of Grass and Sky by Mary Lyn Ray and E.B. Goodale Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesThe House of Grass and Sky by Mary Lyn Ray and E.B. Goodale Press ReleaseCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- SVS News February 2009Document7 pagesSVS News February 2009jameshwhiteNo ratings yet

- IndonesiaDocument8 pagesIndonesiaguinilingjojieNo ratings yet

- Arts Unit 2Document27 pagesArts Unit 2lawrenze visandeNo ratings yet

- (Jan Rensel, Margaret Rodman) Home in The IslandsDocument272 pages(Jan Rensel, Margaret Rodman) Home in The Islandsermar1127No ratings yet

- ngm7 CP PDFDocument8 pagesngm7 CP PDFlauranistNo ratings yet

- Introduction (Eyden)Document2 pagesIntroduction (Eyden)api-3838677100% (1)

- Activity 02Document2 pagesActivity 02Eckereltigre OrbegosoNo ratings yet

- Guboo Ted ThomasDocument5 pagesGuboo Ted ThomasMatheus RochaNo ratings yet

- Settlement Patterns and Housing of Central New GuineaDocument45 pagesSettlement Patterns and Housing of Central New GuineauscngpNo ratings yet

- SuppliersDocument2 pagesSuppliersArun AKNo ratings yet

- Lebanese Architecture PDFDocument9 pagesLebanese Architecture PDFaboudehNo ratings yet

- Min 20170324 A16 01Document1 pageMin 20170324 A16 01Anonymous KMKk9Msn5No ratings yet

- Bisterne News Dec 2021Document5 pagesBisterne News Dec 2021api-605229282No ratings yet

- The Life To Come Chapter SamplerDocument21 pagesThe Life To Come Chapter SamplerAllen & Unwin100% (2)

- Tree Magic PDFDocument8 pagesTree Magic PDFNinaNo ratings yet

- Posts Hearths and Thresholds The Iban Lo PDFDocument256 pagesPosts Hearths and Thresholds The Iban Lo PDFAgung Nakula SetiawanNo ratings yet

- The Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellers: An Isabel Soto Archaeology AdventureFrom EverandThe Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellers: An Isabel Soto Archaeology AdventureNo ratings yet

- Lebanese House PDFDocument9 pagesLebanese House PDFtamersfeirNo ratings yet

- The Diary of Anne FrankDocument5 pagesThe Diary of Anne FrankGrapes als Priya100% (1)

- O'Connor - Mrs La Touche of HarristownDocument10 pagesO'Connor - Mrs La Touche of HarristownDerek O'ConnorNo ratings yet

- Dorset Farmhouse. Country Homes & InteriorsDocument10 pagesDorset Farmhouse. Country Homes & InteriorsJuliet Benning100% (1)

- Ferny Pete Rugs!: Published by BS CentralDocument10 pagesFerny Pete Rugs!: Published by BS CentralBS Central, Inc. "The Buzz"No ratings yet

- Love, Duty & Sacrifice: One Hundred years of a Victorian Nottinghamshire familyFrom EverandLove, Duty & Sacrifice: One Hundred years of a Victorian Nottinghamshire familyNo ratings yet

- Family History IntroDocument2 pagesFamily History Introapi-329454821No ratings yet

- Santa Ana Manila Experience: - HeritageDocument31 pagesSanta Ana Manila Experience: - HeritageKristelle Charlotte CruzNo ratings yet

- Vdocuments - MX - Palo Alto Weekly 05242013 Section 2Document20 pagesVdocuments - MX - Palo Alto Weekly 05242013 Section 2andersonvallejosfloresNo ratings yet

- Back Roads Kaipara Issue 4Document3 pagesBack Roads Kaipara Issue 4Storm GeromeNo ratings yet

- Types of Houses Around The World: Ondol (Heated Floor During Winer) Suwon, Korea Gel South Gobi Desert, MongoliaDocument7 pagesTypes of Houses Around The World: Ondol (Heated Floor During Winer) Suwon, Korea Gel South Gobi Desert, MongoliaENo ratings yet

- Combo TestDocument9 pagesCombo TestHồng NhậtNo ratings yet

- 25 Beautiful Homes, October 2017Document2 pages25 Beautiful Homes, October 2017Juliet BenningNo ratings yet

- WritingDocument4 pagesWritingTaylor CarpenterNo ratings yet

- The Tudors PackDocument16 pagesThe Tudors PackMusdalifah HalimNo ratings yet

- George Muller LifestyleDocument2 pagesGeorge Muller LifestyleTolulope OlakitanNo ratings yet

- Myddle: The life and times of a Shropshire farmworker's daughter in the 1920sFrom EverandMyddle: The life and times of a Shropshire farmworker's daughter in the 1920sNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Family Days in Vietnam OfficialDocument9 pagesGroup 2 Family Days in Vietnam OfficialNgô LưuNo ratings yet

- Timeline 2Document1 pageTimeline 2Tajimi Faith CastañoNo ratings yet

- ST Oswald's House PDFDocument2 pagesST Oswald's House PDFpjmc1716No ratings yet

- Scan 0003Document4 pagesScan 0003EdwardsRealtyTeamNo ratings yet

- That HooDoo You Do! (The J. Col - Robert P. RobertsonDocument855 pagesThat HooDoo You Do! (The J. Col - Robert P. RobertsonZymi Smilez82% (11)

- Team 5: 1. Lê Thị Hoa 2. Lê Huyền Anh 3. Bùi Huy Hoàng 4. Trần Công HoàngDocument13 pagesTeam 5: 1. Lê Thị Hoa 2. Lê Huyền Anh 3. Bùi Huy Hoàng 4. Trần Công HoàngTran Cong Hoang (BTEC HN)No ratings yet

- Edel Quinn Pull Up Banners X 3Document3 pagesEdel Quinn Pull Up Banners X 3JNo ratings yet

- Paradise, At Last: Ashes to Ashes, East to West; A Swiss-American Family's Migration, #2From EverandParadise, At Last: Ashes to Ashes, East to West; A Swiss-American Family's Migration, #2No ratings yet

- Adler and Gibb Tim CrouchDocument2 pagesAdler and Gibb Tim CrouchMacarena C. AndrewsNo ratings yet

- big 4 9 tập 1Document101 pagesbig 4 9 tập 1lucnguyenNo ratings yet

- A Review On Investigation of Casting Defects With SimulationDocument5 pagesA Review On Investigation of Casting Defects With SimulationInternational Journal of Innovations in Engineering and ScienceNo ratings yet

- Where The Walls Whisper: TravelDocument8 pagesWhere The Walls Whisper: TravelMohit JangidNo ratings yet

- Rennaisance PeriodDocument3 pagesRennaisance PeriodDiana Niña Jean LuiNo ratings yet

- LI - L4 - End - Practice - Test - Reading - 1Document11 pagesLI - L4 - End - Practice - Test - Reading - 1Lizbeth Katherine PradaNo ratings yet

- Egypt in Its African Context Note 3Document62 pagesEgypt in Its African Context Note 3xdboy2006100% (2)

- Chinese LiteratiDocument4 pagesChinese LiteratiJong PerrarenNo ratings yet

- Hum2 Lesson1 PDFDocument33 pagesHum2 Lesson1 PDFJohn Paul TaromaNo ratings yet

- Civil Works: List of Approved Makes/AgenciesDocument2 pagesCivil Works: List of Approved Makes/AgenciesprudhiviNo ratings yet

- Actors Workout GuideDocument7 pagesActors Workout GuideNina SaboNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan IX-EnglezaDocument9 pagesLesson Plan IX-EnglezaSonikkaNo ratings yet

- 1 Durham CathedralDocument11 pages1 Durham CathedralAdi KaviwalaNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Human Anatomy 7th Edition Martini Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Human Anatomy 7th Edition Martini Test Bank PDF Full Chapterallisontaylorfnrqzamgks100% (8)

- Fayum Mummy PortraitsDocument19 pagesFayum Mummy PortraitsLemuel BacliNo ratings yet

- 5 Famous Poems by Robert Frost A) From North of Boston (1914)Document10 pages5 Famous Poems by Robert Frost A) From North of Boston (1914)Francisco EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Classical OrderDocument7 pagesClassical OrderKristine Joy LisingNo ratings yet

- Elements Principles: of andDocument36 pagesElements Principles: of andSHIRLEY M. CLARIDADESNo ratings yet

- Michael Hampton Figure Drawing Design An TextDocument241 pagesMichael Hampton Figure Drawing Design An Textjoao vitor100% (4)

- ART. Abstract ArtDocument1 pageART. Abstract ArtCrabanNo ratings yet

- Art Journal 12Document3 pagesArt Journal 12Mafe Nenia MejiasNo ratings yet

- Maternity, Infants & Children - Infant Nursing & TeethingDocument103 pagesMaternity, Infants & Children - Infant Nursing & TeethingThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (3)

- EmporiumDocument5 pagesEmporiumessicajmj100% (1)

- Archl Design CompreDocument50 pagesArchl Design CompreCharleneGraceLimNo ratings yet

- Mesina, Cyril Sp. Art App Bsge - 3A Quiz 1Document3 pagesMesina, Cyril Sp. Art App Bsge - 3A Quiz 1cy100% (2)

- 1 - U1L1-Importance Meaning Assumptions of Art-AAPDocument5 pages1 - U1L1-Importance Meaning Assumptions of Art-AAPFemme ClassicsNo ratings yet