Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prone Vs Supine Positioning For Breast Cancer Radiotherapy

Uploaded by

Jave GajellomaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prone Vs Supine Positioning For Breast Cancer Radiotherapy

Uploaded by

Jave GajellomaCopyright:

Available Formats

LETTERS

cal antipsychotic medications . . . unless they have been ini- physician to initiate an atypical antipsychotic as an aug-

tiated by a psychiatrist.” Aripiprazole and quetiapine are both mentative pharmacotherapy. Atypical antipsychotics are

approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for aug- indeed effective augmentation agents for treatment-

mentation pharmacotherapy of major depressive disorder. resistant major depressive disorder. However, they have a

Given a shortage of psychiatrists,5 and wait times of up to 3 high risk of adverse effects, such as the metabolic syn-

months to see a psychiatrist, and in an age when psychiat- drome and extrapyramidal symptoms, and have been

ric disorders are the leading source of medical disability, it associated with rare but serious complications, such as

is imperative for primary care physicians to learn how to tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.4

safely use any and all available interventions, including the There is no evidence that atypical antipsychotics are

appropriate use and monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. more effective than tricyclics, lithium, thyroid hormone,

Jordan F. Karp, MD or other available augmentation therapies for major

Ellen M. Whyte, MD depressive disorder.5 Therefore, unless a primary care

physician has the expertise to select one of these strate-

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of gies for a patient who has experienced failure with all

Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (karpjf@upmc.edu).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the first- and second-line therapies (psychotherapy, selective

ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Karp reported re- serotonin reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, serotonin nor-

ceiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Alliance for

Research on Schizophrenia and Depression; holding stock in Corcept; and receiv-

epinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and mirtazapine), I

ing medication supplies for investigator-initiated trials from Pfizer and Reckitt Benck- believe that a psychiatrist should be consulted.

iser. Dr Whyte reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Mental Health,

the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s National Center Mary A. Whooley, MD

for Medical Rehabilitation Research, and the National Institute of Neurological Dis- Author Affiliation: Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Fran-

orders and Stroke Small Business Innovation Research; and the provision of study cisco, California (mary.whooley@ucsf.edu).

drugs from Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The author has completed and submitted the ICMJE

Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported receiving grants

1. Whooley MA. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in adults with comorbid from the National Institutes of Health, Roche Diagnostics, Gilead Sciences, and

medical conditions: a 52-year-old man with depression. JAMA. 2012;307(17): Somalogic Inc; and travel support from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for

1848-1857. the Clinical Crossroads presentation.

2. Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M, et al; American Academy of Sleep

Medicine. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive air- 1. Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, et al. Delivery of evidence-based treat-

way pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. ment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial.

Sleep. 2006;29(3):375-380. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1921-1928.

3. Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, Camp P, Wells KB. Prevalence of 2. Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for gen-

comorbid anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Arch Fam Med. 1996; eralized anxiety disorder among older adults in primary care: a randomized clini-

5(1):27-35. cal trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1460-1467.

4. Skapinakis P. The 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale had high sensi- 3. Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang A, et al. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive

tivity and specificity for detecting GAD in primary care. Evid Based Med. 2007; behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in primary-care settings. Depress Anxiety.

12(5):149. 2009;26(3):235-242.

5. Robiner WN. The mental health professions: workforce supply and demand, 4. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major de-

issues, and challenges. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(5):600-625. pressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J

Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

In Reply: Drs Karp and Whyte raise 2 important points re- 5. Fleurence R, Williamson R, Jing Y, et al. A systematic review of augmentation

strategies for patients with major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;

garding the management of depression in primary care set- 42(3):57-90.

tings. First, depressive symptoms can overlap with those of

OSA. Therefore, in a patient with OSA, it is important to

inquire about compliance with the CPAP device, verify proper

mask fit, and consider modafinil if excessive daytime sleepi- RESEARCH LETTER

ness persists despite appropriate therapy.

Prone vs Supine Positioning

Second, patients with depression have a high prevalence

for Breast Cancer Radiotherapy

of comorbid anxiety disorders, and screening with the 2-item

Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale can improve case iden- To the Editor: Adjuvant radiotherapy to the breast contrib-

tification. Whether routine screening for anxiety disorders utes to improved outcomes in breast cancer patients after

benefits primary care patients has not been determined. How- breast preservation surgery.1 However, whole breast radio-

ever, first-line therapies (cognitive behavioral therapy and therapy is associated with damage to the heart and lung, in-

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are the same for both creased cardiovascular mortality, and lung cancer develop-

depression and anxiety disorders,1-3 so patients treated for ment, with risks that remain 15 to 20 years after treatment.2

major depressive disorder will usually receive therapy for These consequences occur when breast cancer patients are

both conditions. treated supine. Preliminary data on prone positioning sug-

Karp and Whyte also are concerned about my state- gest that radiation exposure to the heart and lung can be

ment that “Primary care physicians should not prescribe reduced compared with supine positioning3,4 with similar

atypical antipsychotic medications . . . unless they have efficacy.5 To test the hypothesis that prone positioning is

been initiated by a psychiatrist.” They suggest there are superior to standard supine positioning, we compared the

cases when it might be appropriate for a primary care volume of heart and lung within the radiation field in a pro-

©2012 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, September 5, 2012—Vol 308, No. 9 861

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/04/2023

LETTERS

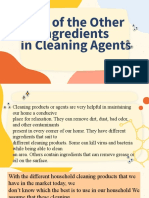

Figure. Example of a Patient With Better Exclusion of the Heart and Lung When Prone

A Supine position B Prone position

A P

Target

(breast tissue)

R L L Lung R

Latissimus Lung

Heart dorsi

Liver

Liver Heart

Lung

Target

(breast tissue)

Latissimus

dorsi

Placing the posterior edge of the fields on a plane connecting the midline to the anterior extent of the latissimus dorsi muscle ensures comparable breast coverage.

spective study of patients who underwent simulation in both Results. Four hundred consecutive patients were pro-

positions. spectively accrued, approximately 60% of those eligible. Me-

Methods. From November 15, 2005, to December 26, dian age was 56.3 years (range, 30.7-94.3 years). Ethnicity

2008, patients with stage 0-IIA breast cancer, segmental mas- was 322 (80.5%) white, 22 (5.5%) black, 21 (5.2%) His-

tectomy, negative surgical margins, and 3 or fewer in- panic, 28 (7%) Asian, and 7 (1.7%) of other ethnicity. The

volved lymph nodes referred to New York University Ra- primary insurance carrier was private in 310 (77%) pa-

diation Oncology were eligible for the study. Each patient tients, Medicare in 76 (19%), and Medicaid in 14 (4%).

underwent 2 computed tomography (CT) simulation scans, Eighty-six (21.5%) patients had ductal carcinoma in situ.

first supine and next prone. The dose from the second CT Among the 314 (78.5%) patients with invasive breast can-

was justified ethically because additional imaging enabled cer, 47 (14.96%) had involved sentinel or axillary lymph

the treating physician to choose the position that best spared nodes.

heart and lung. The treating physician contoured target and In all patients, the prone position was associated with

normal structures and placed the treatment fields. Compa- reduced in-field lung volumes compared with supine

rable coverage of the breast regardless of position was en- (TABLE) (mean difference: 104.6 cm3 [95% CI, 94.26-

sured by placing the posterior edge of the field on a plane 114.95 cm3], an 86.2% reduction for right breast cancer;

connecting the midline to the anterior extent of the latissi- 89.85 cm3 [95% CI, 80.16-99.55 cm3], a 91.1% reduction

mus dorsi muscle, visualized at CT (FIGURE). In-field heart for left breast cancer). In patients with left breast cancer, the

and lung volumes were then measured by 2 physicists (J.K.D. prone position was associated with a reduction of in-field

and G.J.) as reliable surrogates for dose.4 Three breast vol- heart volumes compared with supine (mean difference: 7.5

ume groups were defined (⬍750 cm3, 750-1500 cm3, and cm3 [95% CI, 5.16-9.85 cm3], an 85.7% reduction). How-

⬎1500 cm3). ever, in 15% of patients with left breast cancer, the supine

Two hundred patients per stratum (left and right breast position was associated with less in-field heart volume

cancer) were enrolled to detect differences smaller than ±0.30 compared with prone (mean difference: 6.15 cm3; 95% CI,

SD for each volume parameter between the supine and prone 2.97-9.33 cm3). These reductions were statistically signifi-

positions, using paired t tests with a 2-sided ␣ of .05 and cant regardless of breast volume (with the exception of

power of 80%. Differences in in-field lung and heart vol- heart in women with breast size ⬍750 cm3).

umes (and 95% confidence intervals) between the supine Comment. Prone positioning was associated with a re-

and prone positions for patients with left breast cancer and duction in the amount of irradiated lung in all patients and

in lung volumes for patients with right breast cancer were in the amount of heart volume irradiated in 85% of pa-

estimated. Data analysis was performed using SAS software tients with left breast cancer.

version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc). The study is limited to a single institution. A multi-

All patients provided written informed consent. The institutional prospective trial with outcome measures is war-

New York University institutional review board approved ranted to confirm these findings. If prone positioning bet-

the study. ter protects normal tissue adjacent to the breast, the risks

862 JAMA, September 5, 2012—Vol 308, No. 9 ©2012 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/04/2023

LETTERS

Table. Differences in Volumes of Heart and Lung Between Supine and Prone Positions by Breast Volume and Right vs Left Breast Cancer

Right Breast Cancer a Left Breast Cancer

In-Field Lung Volume, In-Field Lung Volume, In-Field Heart Volume,

Mean (95% CI), cm3 Mean (95% CI), cm3 Mean (95% CI), cm3

Breast Difference of Difference of Change From

Volume, Supine Supine Supine to

cm3 No. Supine Prone Minus Prone b No. Supine Prone Minus Prone b Supine Prone Prone b

⬍750 73 122.80 20.91 101.89 78 90.64 17.56 73.07 3.09 2.60 0.49

(106.90 to (15.54 to (87.05 to (76.80 to (10.59 to (60.42 to (1.56 to (1.17 to (−1.62 to

138.71) 26.29) 116.73) (104.47) 24.54) 85.72) 4.61) 4.02) 2.60)

750-1500 91 120.71 17.47 103.24 84 110.44 3.65 106.78 10.38 0.57 9.81

(105.31 (11.19 to (88.91 to (94.28 to (1.93 to (90.75 to (7.19 to (0.22 to (6.60 to

to 23.74) 117.58) 126.57) 5.38) 122.82) 13.57) 0.92) 13.02)

136.11)

⬎1500 36 120.20 6.66 113.54 38 88.68 1.81 86.87 16.80 0 16.79

(84.11 to (0.96 to (78.58 to (63.63 to (−1.55 to (61.50 to (8.46 to (8.45 to

156.28) 12.36) 148.49) 113.73) 5.17) 112.23) 25.13) 25.13)

Total 200 121.38 16.78 104.60 200 98.58 8.73 89.85 8.75 1.25 7.50

(110.44 (13.15 to (94.26 to (88.77 to (5.72 to (80.16 to (6.53 to (0.66 to (5.16 to

to 20.41) 114.95) 108.39) 11.74) 99.55) 10.97) 1.84) 9.85)

132.32)

a There was no in-field heart volume in any of the patients with right breast cancer.

b The 95% CIs are based on paired t statistics.

of long-term deleterious effects of radiotherapy may be re- Role of the Sponsor: The funding agency of the feasibility study on prone breast

radiotherapy that permitted the current trial had no role in the design and con-

duced. duct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in

the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Silvia C. Formenti, MD

J. Keith DeWyngaert, PhD 1. Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, et al; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative

Gabor Jozsef, PhD Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-

year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual pa-

Judith D. Goldberg, ScD tient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):

Author Affiliations: Departments of Radiation Oncology (Drs Formenti, DeWyn- 1707-1716.

gaert, and Jozsef) (silvia.formenti@nyumc.org) and Environmental Medicine (Dr 2. Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW, Peto R. Long-term mortality from heart dis-

Goldberg), New York University School of Medicine, New York. ease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective co-

Author Contributions: Dr Formenti had full access to all of the data in the study hort study of about 300,000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol.

and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data 2005;6(8):557-565.

analysis. 3. Formenti SC, Gidea-Addeo D, Goldberg JD, et al. Phase I-II trial of prone ac-

Study concept and design: Formenti, DeWyngaert, Goldberg. celerated intensity modulated radiation therapy to the breast to optimally spare

Acquisition of data: Formenti, DeWyngaert, Jozsef. normal tissue. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2236-2242.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Formenti, DeWyngaert, Goldberg. 4. Lymberis SC, Dewyngaert JK, Parhar P, et al. Prospective assessment of opti-

Drafting of the manuscript: Formenti, DeWyngaert, Goldberg. mal individual position (prone versus supine) for breast radiotherapy: volumetric

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Formenti, and dosimetric correlations in 100 patients [published online April 9, 2012]. Int J

Jozsef, Goldberg. Radiation Oncol Biol Physics. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.040.

Statistical analysis: Jozsef, Goldberg. 5. Stegman LD, Beal KP, Hunt MA, Fornier MN, McCormick B. Long-term clinical

Administrative, technical, or material support: Formenti, DeWyngaert. outcomes of whole-breast irradiation delivered in the prone position. Int J Radiat

Study supervision: Formenti, Goldberg. Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(1):73-81.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the

ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Formenti reported

institutional receipt of payment from the David Geffen School of Medicine at the

University of California, Los Angeles, for a presentation at a conference; and in-

stitutional receipt of payment for a continuing medical education course offered CORRECTION

at New York University. Dr Goldberg reported institutional receipt of a cancer cen-

ter support grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Incorrect Author’s Name: In an Editorial entitled “The JAMA Network Journals:

Health. Drs DeWyngaert and Jozsef did not report any disclosures. New Names for the Archives Journals,” published in the July 4, 2012, issue of JAMA

Funding/Support: Federal IDEA grant DAMD17-01-1-0345 from the Department (2012;308[1]:85), one of the names in the byline had the wrong middle initial.

of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program awarded to Dr Formenti enabled the The name should have appeared as Rita F. Redberg, MD, MSc. The article has

initial feasibility study on prone breast radiotherapy that permitted the current trial. been corrected online.

©2012 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, September 5, 2012—Vol 308, No. 9 863

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/04/2023

You might also like

- P76 Depression AnnIntMed 2007Document16 pagesP76 Depression AnnIntMed 2007Gabriel CampolinaNo ratings yet

- Artigo InglesDocument11 pagesArtigo InglesEllen AndradeNo ratings yet

- Prescribing Antipsychotics in Geriatric Patients:: First of 3 PartsDocument8 pagesPrescribing Antipsychotics in Geriatric Patients:: First of 3 PartsAlexRázuri100% (1)

- MetabolicIssuesSevereMentalIllnessReview CITROME SouthernMedJ2005Document7 pagesMetabolicIssuesSevereMentalIllnessReview CITROME SouthernMedJ2005Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- InsomniaDocument14 pagesInsomniaSebastián Camilo DuqueNo ratings yet

- Depression: Annals of Internal MedicinetDocument16 pagesDepression: Annals of Internal MedicinetjesusNo ratings yet

- Tugas Skill - UnlockedDocument9 pagesTugas Skill - Unlockednamasaya1No ratings yet

- DepressionDocument16 pagesDepressionLEONARDO ANTONIO CASTILLO ZEGARRA100% (1)

- Manejo Depresion 1Document10 pagesManejo Depresion 1Luis HaroNo ratings yet

- Park, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionDocument10 pagesPark, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionFabian WelchNo ratings yet

- 1er ArticuloDocument7 pages1er ArticuloAlexRázuriNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology AntidepresantDocument17 pagesPharmacology Antidepresantandhita96No ratings yet

- Datadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDocument9 pagesDatadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDiana IstrateNo ratings yet

- Panic Disorder: A Common Yet Underdiagnosed and Misunderstood Psychological Illness in PakistanDocument3 pagesPanic Disorder: A Common Yet Underdiagnosed and Misunderstood Psychological Illness in PakistanSharii AritonangNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2300184Document11 pagesNejmoa 2300184Hector RivasNo ratings yet

- The Role of Psychotropic Medications in The ManagementDocument24 pagesThe Role of Psychotropic Medications in The ManagementloloasbNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument8 pagesGeneralized Anxiety DisorderTanvi SharmaNo ratings yet

- References: Monotherapy Versus Polypharmacy For Hospitalized Psychiatric PatientsDocument1 pageReferences: Monotherapy Versus Polypharmacy For Hospitalized Psychiatric PatientsLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- JCPDocument11 pagesJCPChangNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkDocument6 pagesTreatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkStephNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasDocument15 pagesTrastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasManuel Dacio Castañeda CabelloNo ratings yet

- Provisional: Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment OptionsDocument73 pagesProvisional: Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment OptionsDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Benign Fasciculations and Health AnxietyDocument9 pagesThe Association Between Benign Fasciculations and Health AnxietyTravis ReddenNo ratings yet

- Artigo Lancet Medicamentos AnsiedadeDocument10 pagesArtigo Lancet Medicamentos AnsiedadeRebecca DiasNo ratings yet

- Paper 2Document5 pagesPaper 2fernanda cornejoNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument12 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofwardahNo ratings yet

- Adjusting To Traumatic Stress ResearchDocument2 pagesAdjusting To Traumatic Stress ResearchSimonia CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Quetiapine or Haloperidol As Monotherapy For Bipolar Mania A 12week Doubleblind Randomised Placebo Controlled Trial - Europ Neuropsych 2005Document13 pagesQuetiapine or Haloperidol As Monotherapy For Bipolar Mania A 12week Doubleblind Randomised Placebo Controlled Trial - Europ Neuropsych 2005Pedro GargoloffNo ratings yet

- A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Quetiapine and Paroxetine As Monotherapy in Adults With Bipolar Depression (EMBOLDEN II)Document12 pagesA Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Quetiapine and Paroxetine As Monotherapy in Adults With Bipolar Depression (EMBOLDEN II)HugoMattosNo ratings yet

- Severe Illness Anxeit Treated by Integrating Inpatient Psychotherapy With Medical Care and Minimizing ReassuranceDocument6 pagesSevere Illness Anxeit Treated by Integrating Inpatient Psychotherapy With Medical Care and Minimizing ReassuranceJan LAWNo ratings yet

- CorrespondenceDocument3 pagesCorrespondenceklysmanu93No ratings yet

- Should Psychiatrists Use Atypical Antipsychotics To Treat Nonpsychotic Anxiety?Document9 pagesShould Psychiatrists Use Atypical Antipsychotics To Treat Nonpsychotic Anxiety?Andoni Trillo PaezNo ratings yet

- ASCP Corner Increased Risk of Cerebrovascular Adverse Events and Death in Elderly Demented PatienDocument1 pageASCP Corner Increased Risk of Cerebrovascular Adverse Events and Death in Elderly Demented PatienSantosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Psychological And Behavioral Treatment Of Insomnia UpdateDocument17 pagesPsychological And Behavioral Treatment Of Insomnia UpdateM SNo ratings yet

- AripiprazolDocument15 pagesAripiprazolFabrício de Souza XavierNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument16 pagesGeneralized Anxiety Disordernns5rrg2rdNo ratings yet

- The Naturalistic Course of Major Depression N The Absence of Somatic TherapyDocument6 pagesThe Naturalistic Course of Major Depression N The Absence of Somatic TherapyCarlos CostaNo ratings yet

- Management of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical AntipsychoticsDocument17 pagesManagement of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical Antipsychoticsnithiphat.tNo ratings yet

- Treating Migraine and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDocument3 pagesTreating Migraine and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesCharbel Rodrigo Gonzalez SosaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Depression and Suicidal Patients in The Emergency RoomDocument15 pagesEvaluation of Depression and Suicidal Patients in The Emergency RoomjuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- NEJMPsilocybinDocument12 pagesNEJMPsilocybinpaul casillasNo ratings yet

- Nej MCP 2305428Document10 pagesNej MCP 2305428Josue LeivaNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDocument10 pagesLong-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDewi SariNo ratings yet

- Komorbid 1Document15 pagesKomorbid 1ErioRakiharaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareMaria Jose OcNo ratings yet

- Anorexia Nervosa - Aetiology, Assessment, and TreatmentDocument13 pagesAnorexia Nervosa - Aetiology, Assessment, and TreatmentDouglas SantosNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1059131106001208Document5 pagesPi Is 1059131106001208Murli manoher chaudharyNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative StudyDocument6 pagesA Qualitative StudyPaula CelsieNo ratings yet

- AP JayubDocument4 pagesAP JayubUsama Bin ZubairNo ratings yet

- 2016 AHS Manejo de Migraña en EMGDocument30 pages2016 AHS Manejo de Migraña en EMGSolange Vargas LiclaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal SkizoafektifDocument7 pagesJurnal SkizoafektifkhairinanurulNo ratings yet

- Contraception For Women With Psychiatric DisordersDocument14 pagesContraception For Women With Psychiatric DisordersFourtiy mayu sariNo ratings yet

- E Cacy of Modern Antipsychotics in Placebo-Controlled Trials in Bipolar Depression: A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesE Cacy of Modern Antipsychotics in Placebo-Controlled Trials in Bipolar Depression: A Meta-AnalysisRisda AprilianiNo ratings yet

- H1P S A C: Sychological Ymptoms in Dvanced AncerDocument11 pagesH1P S A C: Sychological Ymptoms in Dvanced AnceryuliaNo ratings yet

- Boston Medical and Surgical Journal Volume 359 Issue 26 2008 (Doi 10.1056/nejmoa0804633) Walkup, John T. Albano, Anne Marie Piacentini, John Birmaher, - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, SertralineDocument14 pagesBoston Medical and Surgical Journal Volume 359 Issue 26 2008 (Doi 10.1056/nejmoa0804633) Walkup, John T. Albano, Anne Marie Piacentini, John Birmaher, - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, SertralineKharisma FatwasariNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0025712514000893Document32 pagesPi Is 0025712514000893Christoph HockNo ratings yet

- 121 Full PDFDocument6 pages121 Full PDFMatheus SilvaNo ratings yet

- ENERGY PSYCH THERAPY EVIDENCEDocument19 pagesENERGY PSYCH THERAPY EVIDENCElandburender100% (1)

- Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in The Diagnosis and Management of The Adult Psychiatric Patient in The Emergency DepartmentDocument19 pagesClinical Policy: Critical Issues in The Diagnosis and Management of The Adult Psychiatric Patient in The Emergency Departmentedurne19907249No ratings yet

- Your Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022From EverandYour Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022No ratings yet

- The State of The World's RefugeesDocument2 pagesThe State of The World's RefugeesabhiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Consumer Pharmacuteical AdvertisisngDocument3 pagesResearch Paper On Consumer Pharmacuteical Advertisisngyashjadhav08No ratings yet

- Dysfunctional Adiposity and The Risk of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes inDocument10 pagesDysfunctional Adiposity and The Risk of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes inWeird XgamingNo ratings yet

- Spending Differences Associated With The Medicare Physician Group Practice DemonstrationDocument9 pagesSpending Differences Associated With The Medicare Physician Group Practice DemonstrationWeird XgamingNo ratings yet

- Challenges To Excellence in Child Health ResearchDocument2 pagesChallenges To Excellence in Child Health ResearchabhiNo ratings yet

- Multiply Recurrent Solitary Fibrous Tumor of The Orbit Without Malignant Degeneration - A 45-Year Clinicopathologic Case StudyDocument3 pagesMultiply Recurrent Solitary Fibrous Tumor of The Orbit Without Malignant Degeneration - A 45-Year Clinicopathologic Case StudyJave GajellomaNo ratings yet

- Intralesional Ethanol For An Unresectable Epithelial Inclusion CystDocument2 pagesIntralesional Ethanol For An Unresectable Epithelial Inclusion CystJave GajellomaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Physician-, Biomarker-, and Symptom-Based Strategies For Adjustment of Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy in Adults With AsthmaDocument11 pagesComparison of Physician-, Biomarker-, and Symptom-Based Strategies For Adjustment of Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy in Adults With AsthmaDasi HipNo ratings yet

- Users' Views of Dietary SupplementsDocument3 pagesUsers' Views of Dietary SupplementsJave GajellomaNo ratings yet

- Basic Chemistry For Pre KDocument28 pagesBasic Chemistry For Pre KJave GajellomaNo ratings yet