Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Myasthenia Gravis: Murali Thavasothy DCH MRCP FRCA Nicholas Hirsch FRCA

Uploaded by

Mirela CiobanescuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Myasthenia Gravis: Murali Thavasothy DCH MRCP FRCA Nicholas Hirsch FRCA

Uploaded by

Mirela CiobanescuCopyright:

Available Formats

Myasthenia gravis

Murali Thavasothy DCH MRCP FRCA

Nicholas Hirsch FRCA

Aetiology Table 1 Classification of myasthenia gravis

Key points

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune Type

Myasthenia gravis is an

condition in which IgG autoantibodies interact I Ocular signs and symptoms only

autoimmune disease in

with the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors IIA Generalised mild muscle weakness responding

which IgG antibodies

well to therapy

decrease postsynaptic (AChR) at the nicotinic neuromuscular junction IIB Generalised moderate muscle weakness

receptor density at the (NMJ). The AChR antibodies reduce the num- responding less well to therapy

neuromuscular junction III Acute fulminating presentation and/or

ber of functional receptors by blocking attach-

The cardinal feature is respiratory dysfunction

ment of acetylcholine molecules, by increasing IV Myasthenic crisis requiring artificial ventilation

weakness and fatigability

of voluntary muscles the rate of degradation of the receptors and by

Pre-operative manage- complement-induced damage to the NMJ.

ment must include care- Thus, patients with MG have a reduced AChR exercise (fatigability) and is relieved with rest.

ful assessment of respira- density and, on average, have 30% of the nor- In 15% of patients, the disease is confined to the

tory and bulbar muscle eyes with diplopia and ptosis being the most

mal number of AChR. Therefore, the normal

function and optimisation

‘margin of safety’ found at the NMJ in health is common symptom and sign. However, in the

of medication

lost. remaining 85%, the disease is generalised with

Patients are extremely

sensitive to non-depolar- Although it is widely accepted that MG is an weakness of ocular, facial, bulbar and limb

ising neuromuscular antibody-mediated condition, the origin of the muscles. Although respiratory muscles are nor-

blocking drugs mally affected only mildly, respiratory failure

process remains uncertain. However, the thy-

There may be resistance mus gland has been implicated as a possible requiring artificial ventilation may occur, i.e.

to the effects of succinyl- myasthenic crisis. The distribution of weakness

choline generator of the immune process. The gland is

abnormal in 75% of patients with MG (85% and the response to drug therapy allows classi-

A period of postopera-

hyperplasia, 15% thymoma). One hypothesis fication of MG (Table 1).

tive ventilation may be

necessary following suggests that the B and T lymphocytes within

major surgery Diagnosis

the thymus become sensitised to AChR found

on ‘myoid’ cells within the gland. The reason The diagnosis of MG depends on a careful his-

for a breakdown in the normal immune toler- tory and examination, pharmacological tests,

ance between these components in the thymus electromyography (EMG) and detection of the

gland remains obscure. anti-AChR antibodies. Although historically an

exaggerated response to a small dose of curare

was taken as evidence supporting the diagnosis

Clinical features of MG, the Tensilon test, in which up to 10 mg

Murali Thavasothy

Myasthenia gravis affects 1 in 10,000 of the of edrophonium is administered i.v., is the stan-

DCH MRCP FRCA

Specialist Registrar, Department of population, predominantly young women dard pharmacological test. Patients with MG

Anaesthesia,The Royal Free (20–30 yr) and older men (60–70 yr). The often show a marked improvement in muscle

Hospital, Pond Street,

London NW3 2GQ, UK reduced AChR density seen in MG results in power after 30 s and this is sustained for

Nicholas Hirsch FRCA decreased amplitude of action potentials in the approximately 5 min. A negative result does not

Consultant Anaesthetist,The postsynaptic region causing a failure in initia- exclude MG. The most commonly used EMG

National Hospital for Neurology and tion of muscle fibre contraction. When this

Neurosurgery, Queen Square,

test in the diagnosis of MG is the recording of

London WC1N 3BG, UK occurs at many NMJs, it is manifest clinically compound muscle action potentials (CMAP)

(for correspondence)

Tel: 020 7829 8711

as weakness of voluntary muscle – the cardinal following repetitive stimulation of the motor

Fax: 020 7829 8734 feature of MG. The weakness is accentuated by nerve. In MG, repetitive stimulation results in a

British Journal of Anaesthesia | CEPD Reviews | Volume 2 Number 3 2002

88 © The Board of Management and Trustees of the British Journal of Anaesthesia 2002

Myasthenia gravis

Table 2 Autoimmune conditions associated with myasthenia gravis Thymectomy

Hyper/hypothyroidism Polymyositis/dermatomyositis Thymectomy is indicated for most patients with MG up to the

Rheumatoid disease Systemic lupus erythematosis age of 60 years and for those patients with a thymoma. The lat-

Scleroderma Pernicious anaemia ter may invade local mediastinal structures and ‘seed’ along the

Psoriasis/vitiligo

pleura. In patients with thymic hyperplasia, the aim is to induce

remission, or at least to produce sufficient improvement, to allow

the dose of immunosuppressive drugs to be reduced. The benefi-

progressive decrease (> 10%) in CMAP – a finding termed

cial effects may take several years to realise fully. Complete

decrement or fade. Single muscle fibre recordings are a more

removal of thymic tissue is necessary. Therefore, full exposure

sensitive indicator of neuromuscular junction blockade, but it

via a median sternotomy is the usual approach. However, some

must be stressed that all EMG abnormalities seen are not spe-

advocate removal via a cervical approach and mediastinoscopy.

cific for MG. Anti-AChR antibodies are detected in 80–85% of

patients with MG and are pathognomonic for the disease. Plasma exchange

Disorders associated with myasthenia gravis Plasma exchange is reserved for producing short-term remission

of myasthenic weakness in patients with a myasthenic crisis or

The immunological basis of MG is further re-inforced by the

those patients who need improvement before thymectomy. The

wide variety of other autoimmune diseases associated with the

reduction in the level of anti-AChR antibodies largely correlates

condition. These are listed in Table 2.

with the improvement in muscle power. Improvement is general-

ly seen within days of the exchange, but is usually short lived.

Treatment Complications include worsening of pre-existing infection, intra-

Standard treatment includes anticholinesterase and immunosup- venous catheter sepsis and haemodynamic instability.

pression therapy and thymectomy. In addition, short-term

improvement of myasthenic weakness may be effected by plas- Intravenous immunoglobulin

ma exchange and i.v. immunoglobulin. It must be remembered The indications for administering i.v. immunoglobulin are simi-

that some drugs may exacerbate myasthenic weakness. lar to those of plasma exchange. Improvement occurs within

days and may be sustained for months. Complications include

Anticholinesterase therapy

headaches and, rarely, renal failure.

The aim of anticholinesterase therapy is to enhance neuromuscu-

lar transmission by delaying degradation of ACh at the NMJ. Avoidance of drugs exacerbating myasthenia gravis

Pyridostigmine is the most commonly used drug in the UK. It Some drugs can worsen myasthenic weakness and should be

acts within 30 min, has a peak effect at 2 h and a clinical half-life avoided. The polymyxin group of antibacterial drugs cause

of approximately 4 h. Although often very effective initially, its blocking of AChR ion channels and the aminoglycoside antibi-

effects may diminish over months and most patients require otics decrease ACh release and postsynaptic AChR sensitivity.

immunosuppression. Procainamide, quinine and β-adrenergic receptor blocking drugs

may exacerbate weakness.

Immunosuppression therapy

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment. Prednisolone is Anaesthetic management

given initially at 20 mg day–1 and gradually increased to 60 Anaesthetic management depends on the severity of disease and

mg day–1. Many patients show a worsening of their weakness in type of surgery being considered. Local and regional anaesthesia

the first 2 weeks of therapy. Once MG is controlled, the dose is should be employed when possible. General anaesthesia requires

gradually decreased to the lowest effective alternate day regimen. meticulous pre-operative and peri-operative care.

Azathioprine 1–2 mg kg–1 day–1 is often given in conjunction

with prednisolone in order to allow a reduction in the dose of cor- Pre-operative considerations

ticosteroid. Cyclosporine 5 mg kg–1 day–1 has been used as an Patients undergoing major elective surgical procedures should

alternative to prednisolone, but its high cost and nephrotoxicity be admitted 48 h prior to surgery. This allows detailed assess-

may limit its use. ment and monitoring of respiratory and bulbar function as

British Journal of Anaesthesia | CEPD Reviews | Volume 2 Number 3 2002 89

Myasthenia gravis

well as allowing adjustment of anticholinesterase and corti- ventilation. Many anaesthetists achieve tracheal intubation by

costeroid medication, if indicated. Chest physiotherapy is deepening anaesthesia using inhalational anaesthetic agents.

started at this time. Patients with severe MG may need a Patients with MG are more sensitive to the neuromuscular

course of plasma exchange or i.v. immunoglobulin before blocking effects of these agents and they often provide suffi-

surgery is considered. cient muscle relaxation without having to resort to the use of

The airway must be assessed carefully as associated neuromuscular blockers. Most avoid the latter because of the

rheumatoid disease may limit neck extension and flexion. In abnormal responses of MG patients. These responses are seen

addition, although unusual, a large thymoma may cause dis- even in patients with purely ocular myasthenia and those in

tortion and compression of the trachea. Respiratory muscle remission. Because of the reduced number of functional post-

function may be assessed in a number of ways, but serial mea- synaptic AChR, there is often a relative resistance to usual

surements of forced vital capacity (FVC) are the most repro- doses of succinylcholine and higher doses may be required.

ducible and easily performed test on the general ward. Pre- However, this may be followed by the development of a phase

operative factors that correlate with the need for prolonged II block.

ventilation following thymectomy include FVC < 2.9 litres, a In contrast, patients with MG are extremely sensitive to

history of chronic respiratory disease, grades III and IV MG non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs. This sensi-

and a long history of the disease (> 6 yr). tivity varies according to agent. Thus, only one-tenth of the

Care must also be taken during the pre-operative assessment dose of tubocurare or pancuronium may be required for ade-

to exclude associated autoimmune disease (Table 2). Thyroid quate relaxation whereas 30–40% of the normal dose of

function testing is essential as approximately 15% of MG atracurium or vecuronium may be needed. The latter two

patients have some abnormality of the gland. Following pre- agents have gained popularity as they have a more predictable

operative evaluation, a full explanation of the procedure and duration of action than older agents. Furthermore, reversal of

anaesthetic course is given to the patient and this should their affects with anticholinesterases is often unnecessary and

include the possibility of needing postoperative mechanical this avoids the potential for a cholinergic crisis in the postop-

ventilation. erative period.

Many avoid the use of sedative premedication but, in the

absence of respiratory muscle compromise, it may be used

Postoperative management

safely. Antimuscarinic agents such as glycopyrronium are The majority of patients who have well-controlled MG pre-oper-

helpful in reducing secretions. Corticosteroid treatment is atively can have their tracheas safely extubated at the end of the

continued pre-operatively and additional hydrocortisone procedure. This especially applies to patients undergoing trans-

administered on the day of surgery. Traditionally, anti- cervical thymectomy who are less likely to require a period of

cholinesterase therapy is withheld on the morning of surgery postoperative ventilation than those undergoing trans-sternal

as myasthenic patients often do not require these drugs in the thymectomy. They should be nursed in a high-dependency area

immediate postoperative period. In theory, anticholinesterases and adequate analgesia provided. A combination of non-

may prolong the action of succinylcholine and possibly steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and parenteral opioids usually

increase the requirements of non-depolarising neuromuscular provides good analgesia. Anticholinesterases are restarted at a

blocking drugs (but see below). reduced dose in the immediate postoperative period and are then

increased as necessary as the patient becomes ambulant.

Induction and maintenance of anaesthesia

Routine monitoring is supplemented with invasive blood pres- Key references

sure measurement in those patients undergoing median ster- Baraka A. Anaesthesia and myasthenia gravis. Can J Anaesth 1992; 39:

1992–6

notomy for thymectomy. Neuromuscular transmission should

Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1797–808

be monitored continuously during the procedure.

Krucylak PE, Naunheim KS. Preoperative preparation and anaesthetic

Following pre-oxygenation, anaesthesia is induced with management of patients with myasthenia gravis. Semin Thorac

thiopental or propofol. The trachea is then intubated using an Cardiovasc Surg 1999; 11: 47–53

oro- or nasotracheal tube. The latter may be preferred if there is

a possibility of requiring prolonged postoperative mechanical See multiple choice questions 62–66.

90 British Journal of Anaesthesia | CEPD Reviews | Volume 2 Number 3 2002

You might also like

- 2 Myasthenia Gravis and MS 2Document50 pages2 Myasthenia Gravis and MS 2Rawbeena RamtelNo ratings yet

- Miastenia GravisDocument28 pagesMiastenia Gravismariateresajijon7No ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis and Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome - Continuum December 2016Document28 pagesMyasthenia Gravis and Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome - Continuum December 2016Habib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Motor Endplate Disorders Myasthenia Gravis Overview and DefinitionDocument4 pagesMotor Endplate Disorders Myasthenia Gravis Overview and DefinitionPJHGNo ratings yet

- 51.differential Diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis - A ReviewDocument11 pages51.differential Diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis - A ReviewSeptime TyasNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis Anesthetic Implications and ManagementDocument31 pagesMyasthenia Gravis Anesthetic Implications and Managementaashish45No ratings yet

- Review: Myasthenic CrisisDocument11 pagesReview: Myasthenic CrisisRaisha TriasariNo ratings yet

- RJN 2017 2 Art-04Document3 pagesRJN 2017 2 Art-04Ana GabrielaNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis and Other Neuromuscular Junction DisordersDocument8 pagesMyasthenia Gravis and Other Neuromuscular Junction Disordersidno1008No ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: A Review: Hideyuki Matsumoto, MD, PHD and Yoshikazu Ugawa, MD, PHDDocument7 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: A Review: Hideyuki Matsumoto, MD, PHD and Yoshikazu Ugawa, MD, PHDZainal AbidinNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Junction DisordersDocument32 pagesNeuromuscular Junction Disordersepic sound everNo ratings yet

- L 7 ANESTHESIS Myasthenia GravisDocument20 pagesL 7 ANESTHESIS Myasthenia Graviskatherinerance331No ratings yet

- Myesthenia Gravis MedscapeDocument8 pagesMyesthenia Gravis MedscapeSarah OvinithaNo ratings yet

- Bja MGDocument6 pagesBja MGVignesh VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Referat MG Desya BismillahDocument20 pagesReferat MG Desya BismillahDesya BillaNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rodica BălașaDocument31 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rodica BălașaIstván MáthéNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular DisordersDocument3 pagesNeuromuscular DisordersMaharaniDewiNo ratings yet

- Source 3Document3 pagesSource 3PJHGNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Junction DisorderDocument10 pagesNeuromuscular Junction DisorderZosmita Shane GalgaoNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis Lecture 12Document59 pagesMyasthenia Gravis Lecture 12Pop D. MadalinaNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument11 pagesMyasthenia GravisParvathy RNo ratings yet

- Presented By: VIVEK DEVDocument38 pagesPresented By: VIVEK DEVFranchesca LugoNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument17 pagesMyasthenia GravisYanski DarmantoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Trigeminal Neuralgia 1Document12 pagesJurnal Trigeminal Neuralgia 1nabilla putriNo ratings yet

- MyasteniaDocument7 pagesMyastenialmcarmonaNo ratings yet

- Lambru2021 2Document12 pagesLambru2021 2Deyvid CapeloNo ratings yet

- MG Desya BismillahDocument20 pagesMG Desya BismillahDesya BillaNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis in Clinical Practice: Miastenia Gravis Na Prática ClínicaDocument9 pagesMyasthenia Gravis in Clinical Practice: Miastenia Gravis Na Prática ClínicaMasDhedotNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis ReferenceDocument19 pagesMyasthenia Gravis ReferenceIka Wulan PermataNo ratings yet

- Trigeminal Neuralgia - A Practical GuideDocument12 pagesTrigeminal Neuralgia - A Practical Guide전영우No ratings yet

- Myastenia Gravis PDFDocument7 pagesMyastenia Gravis PDFAdrian CiurciunNo ratings yet

- MG 2Document5 pagesMG 2vaishnaviNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Children WithDocument5 pagesAnaesthesia For Children Withnanang hidayatullohNo ratings yet

- Debilidad Muscular en UciDocument16 pagesDebilidad Muscular en UcipakokorreaNo ratings yet

- Crisis MiastenicaDocument12 pagesCrisis MiastenicaOsvaldo CortésNo ratings yet

- Update On Ocular Myasthenia GravisDocument12 pagesUpdate On Ocular Myasthenia GravisAnonymous QLadTClydkNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Myasthenia Gravis: Emerging Clinical and Biological HeterogeneityDocument16 pagesAutoimmune Myasthenia Gravis: Emerging Clinical and Biological HeterogeneityGiuseppeNo ratings yet

- Search Criteria: Table 1Document16 pagesSearch Criteria: Table 1Armansyah Nur DewantaraNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument18 pagesMyasthenia GravisvandanaNo ratings yet

- Step 7 1. Mengapa Pada Skenario Pasien Merasakan Lemah Pada Kelopak Mata Dan Mengapa Paling Berat Dirasakan?Document11 pagesStep 7 1. Mengapa Pada Skenario Pasien Merasakan Lemah Pada Kelopak Mata Dan Mengapa Paling Berat Dirasakan?novkar9No ratings yet

- MG-New and Emerging Treatments (Bmjmed-2023)Document6 pagesMG-New and Emerging Treatments (Bmjmed-2023)Apostolos T.No ratings yet

- Presentation On Myasthenia Gravis: Presented By: Sandhya Harbola M.Sc. Nursing 1 Year PcnmsDocument32 pagesPresentation On Myasthenia Gravis: Presented By: Sandhya Harbola M.Sc. Nursing 1 Year PcnmsShubham Singh Bisht100% (3)

- 114 Clinical Evaluation and Management of Myasthenia Gravis - DONEDocument22 pages114 Clinical Evaluation and Management of Myasthenia Gravis - DONEpyshcotNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: Submitted ToDocument6 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: Submitted ToRomans 6:23No ratings yet

- 156 FullDocument7 pages156 FullDorotea ArlovNo ratings yet

- A Case ReportDocument8 pagesA Case ReportYosephine MulianaNo ratings yet

- CME Article 2010 JulyDocument10 pagesCME Article 2010 JulyIlda EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: Moderator: DR Anitha PG: DR VijethaDocument45 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: Moderator: DR Anitha PG: DR VijethaJerusha VijethaNo ratings yet

- Myastenia GrvaisDocument4 pagesMyastenia GrvaisteenaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia and Myasthenia GravisDocument12 pagesAnaesthesia and Myasthenia Gravis37435rlcNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument11 pagesMyasthenia GravisSandeepSethiNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis - A Review of Current TherapeutiDocument7 pagesMyasthenia Gravis - A Review of Current TherapeutiZainal AbidinNo ratings yet

- ShwetaDocument9 pagesShwetasagar KumarNo ratings yet

- NEJMra 1602678Document12 pagesNEJMra 1602678Olga Manco GuzmánNo ratings yet

- NMJ Disorders: For Clinical I StudentsDocument49 pagesNMJ Disorders: For Clinical I StudentsdenekeNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument32 pagesMyasthenia GravisSandhya HarbolaNo ratings yet

- Maddison 2006Document10 pagesMaddison 2006Mayara MoraisNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: by Neha Mhapralkar MSCBT 12015Document20 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: by Neha Mhapralkar MSCBT 12015Neha MhapralkarNo ratings yet

- Locuri A 2-A Specialitate NOIEMBRIE 2023Document2 pagesLocuri A 2-A Specialitate NOIEMBRIE 2023Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Quinlan 2006Document5 pagesQuinlan 2006Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Mks 054Document7 pagesMks 054Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Guidelines ProcessDocument3 pagesGuidelines ProcessMirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- MKN 051Document5 pagesMKN 051Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics: Acute Labyrinthitis Revealing COVID-19Document3 pagesDiagnostics: Acute Labyrinthitis Revealing COVID-19Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Enter Patient Weight in KG: Anticonvulsant and CNS DrugsDocument1 pageEnter Patient Weight in KG: Anticonvulsant and CNS DrugsMirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Pre Operative Fasting in Children A Guideline.2Document22 pagesPre Operative Fasting in Children A Guideline.2Yulieth VanessaNo ratings yet

- Euroanaesthesia 2022 Full Programme - DBD May22Document53 pagesEuroanaesthesia 2022 Full Programme - DBD May22Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- SodiumChloridesharedcare Guideline14Document2 pagesSodiumChloridesharedcare Guideline14Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Diploma Guide - English 2019 ApprovedDocument11 pagesDiploma Guide - English 2019 ApprovedMinaz PatelNo ratings yet

- Noradrenaline Infusion Rate BSUH Critical CareDocument4 pagesNoradrenaline Infusion Rate BSUH Critical CareAndreiCostei100% (1)

- 2021 ESC Guidelines On Cardiac Pacing andDocument94 pages2021 ESC Guidelines On Cardiac Pacing andLeo Purba100% (1)

- Antibiotic Guidelines (2020) - 0Document55 pagesAntibiotic Guidelines (2020) - 0yudhit bessieNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Guideline On Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitDocument32 pagesESPEN Guideline On Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitDiana MonroyNo ratings yet

- Dannandd PhillllDocument1 pageDannandd PhillllMirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- MetamizoleDocument15 pagesMetamizoleFahri AnugrahNo ratings yet

- Reasons Why Phil Lester Is Phil BesterDocument1 pageReasons Why Phil Lester Is Phil BesterMirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Nume: Varsta: Conditii de Viata Si Munca: Motivele InternariiDocument7 pagesNume: Varsta: Conditii de Viata Si Munca: Motivele InternariiMirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- BM Notes SeniorDocument393 pagesBM Notes SeniorShreya KishorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 27 Chest Injuries Final TermDocument4 pagesChapter 27 Chest Injuries Final Termluwi vitonNo ratings yet

- Health Talk On AnemiaDocument15 pagesHealth Talk On Anemiasimonjosan89% (63)

- Endoscopy For Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Procedures Standard Operating Procedure UHL Gastroenterology LocSSIPDocument15 pagesEndoscopy For Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Procedures Standard Operating Procedure UHL Gastroenterology LocSSIPIlu SinghNo ratings yet

- 10 Penyakit Terbanyak Di Rawat Jalan Di Puskesmas Provinsi Dki Jakarta TW I Tahun 2019Document9 pages10 Penyakit Terbanyak Di Rawat Jalan Di Puskesmas Provinsi Dki Jakarta TW I Tahun 2019Klinik pratama Iqra' medical centreNo ratings yet

- Osmosis 4Document1 pageOsmosis 4dysa ayu shalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Allopurinol (Drug Study)Document2 pagesAllopurinol (Drug Study)Daisy PalisocNo ratings yet

- Cholecystitis: By: Myla Rojas. BalandraDocument5 pagesCholecystitis: By: Myla Rojas. BalandraMyla Rojas BalandraNo ratings yet

- Sports Taping Techniques Expected OutcomesDocument5 pagesSports Taping Techniques Expected OutcomesMarc Angelo DareNo ratings yet

- PSW1365 Care of The Client With Dementia Assignment Revsion S2023Document11 pagesPSW1365 Care of The Client With Dementia Assignment Revsion S2023Odia OaikhenaNo ratings yet

- Sars-Cov-2 (Covid 19) Detection (Qualitative) by Real Time RT PCRDocument3 pagesSars-Cov-2 (Covid 19) Detection (Qualitative) by Real Time RT PCRShivam GarodiaNo ratings yet

- Majorsol CottonDocument5 pagesMajorsol CottonAries Agro LimitedNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology of The EyeDocument22 pagesAnatomy and Physiology of The EyeBalkos 61No ratings yet

- Contact Dermatitis BADDocument13 pagesContact Dermatitis BADDurgaMadhab TripathyNo ratings yet

- Chapter I 5Document51 pagesChapter I 5RamNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modeling of COVID-19 Spreading With Asymptomatic Infected and Interacting PeoplesDocument23 pagesMathematical Modeling of COVID-19 Spreading With Asymptomatic Infected and Interacting PeoplesYjhvhgjvNo ratings yet

- Formative Test DMS 2021-2022Document37 pagesFormative Test DMS 2021-2022Lidwina ChandraNo ratings yet

- Myofascial and Endodontics. 2022Document15 pagesMyofascial and Endodontics. 2022David MonroyNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury: Barrios, Kevin George BDocument52 pagesSpinal Cord Injury: Barrios, Kevin George B乔治凯文No ratings yet

- AARC Clinical Practice Guideline - Management of Airway EmergenciesDocument7 pagesAARC Clinical Practice Guideline - Management of Airway EmergenciesdoterofthemosthighNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Travel Recommendations by Destination - CDCDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 Travel Recommendations by Destination - CDCAli Ben HusseinNo ratings yet

- Implementation of New Safety Protocols of Calle Arco Restaurant in Pagsanjan, Laguna During Pandemic CrisisDocument42 pagesImplementation of New Safety Protocols of Calle Arco Restaurant in Pagsanjan, Laguna During Pandemic CrisisOliveros John Brian R.No ratings yet

- Pune CME 2011 BrochureDocument4 pagesPune CME 2011 BrochuredrpajaniNo ratings yet

- Endodontics Principles and Practice (139 279)Document141 pagesEndodontics Principles and Practice (139 279)Daniel Ricardo Moreno HernandezNo ratings yet

- Effect of Social Media Health Communication On Knowledge Attitude and Intention To Adopt Health-Enhancing BehavDocument170 pagesEffect of Social Media Health Communication On Knowledge Attitude and Intention To Adopt Health-Enhancing Behavchukwu solomonNo ratings yet

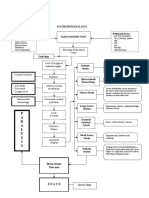

- Pathophysiology: P A R A L Y S I SDocument1 pagePathophysiology: P A R A L Y S I SJordan Garcia AguilarNo ratings yet

- Lower Limb BlocksDocument5 pagesLower Limb BlocksParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Bones and Joints Quiz Questions - Footprints-Science GCSE Science Animations and QuizzesDocument1 pageBones and Joints Quiz Questions - Footprints-Science GCSE Science Animations and Quizzescpcp6n7tc5No ratings yet

- Common River Medicinal Plant Handbook FINAL4Document40 pagesCommon River Medicinal Plant Handbook FINAL4Shime EthiopianNo ratings yet

- Cholinergic DrugsDocument22 pagesCholinergic Drugsmug ashNo ratings yet