Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bankr. Exemption Manual 4.8 Homestead Caps - Section 522 (O), (P), and (Q)

Uploaded by

adfsh-1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bankr. Exemption Manual 4.8 Homestead Caps - Section 522 (O), (P), and (Q)

Uploaded by

adfsh-1Copyright:

Available Formats

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr.

Exemption Manual § 4:8

Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

Bankruptcy Exemption Manual | June 2020 Update

William Houston Browna0

Lawrence R. Ahern, IIIa1

Nancy Fraas MacLeana2

Chapter 4. State Opt Out and Limitations on State Exemptions (Section 522(b))

§ 4:8. Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q)

West's Key Number Digest

West's Key Number Digest, Bankruptcy 2774

West's Key Number Digest, Bankruptcy 2797.1

West's Key Number Digest, Bankruptcy 2798

Legal Encyclopedias

C.J.S., Bankruptcy § 172

C.J.S., Bankruptcy §§ 176 to 177

C.J.S., Bankruptcy § 182

Subsections (o), (p), and (q) of section 522 curb perceived abuses of the homestead exemption. These subsections apply to the

debtor's homestead exemption even if the debtor's homestead choice is controlled by an opt-out state, thus significantly limiting

the opt out. The court in In re Rensin, 600 B.R. 870, 889 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2019), concluded that the sections are “intended

to work together.” The debtor argued that when section 522(p) applied to property purchased within the 1,215 days preceding

bankruptcy that section 522(o) was not applicable, but the court disagreed, holding that both sections 522(o) and (p) could

apply. “Section 522(p) automatically limits the value of a homestead exemption where the home was acquired during the 1,215

days prior to the bankruptcy. Section 522(o) provides for a reduction in the homestead value claimed, including the capped

homestead value when section 522(o) applies, where it is shown that the debtor used non-exempt assets to obtain value in a

homestead with the intent to stymie creditors.” Although the Florida home was acquired within the 1,215 days, the Rensin Court

found that the debtor was not entitled to any Florida homestead exemption because of the application of section 522(o).

10-year look-back for fraudulent transfers—Section 522(o)

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

Subsection (o) enables the trustee to reduce the amount of an exemption by the amount that it might have increased as a result

of efforts to defraud a creditor any time in the 10 years prior to the filing of the petition. 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(o) provides that:

(o) For purposes of subsection (b)(3)(A), and notwithstanding subsection (a), the value of an interest in—

(1) real or personal property that the debtor or a dependent of the debtor uses as a residence;

(2) a cooperative that owns property that the debtor or a dependent of the debtor uses as a residence;

(3) a burial plot for the debtor or a dependent of the debtor; or

(4) real or personal property that the debtor or a dependent of the debtor claims as a homestead;

shall be reduced to the extent that such value is attributable to any portion of any property that the debtor disposed of in the

10-year period ending on the date of the filing of the petition with the intent to hinder, delay, or defraud a creditor and that

the debtor could not exempt, or that portion that the debtor could not exempt, under subsection (b), if on such date the debtor

had held the property so disposed of.

Under section 522(o), prebankruptcy conversion of nonexempt assets to exempt assets is permissible as long as there was no

intent to hinder, delay or defraud a creditor. See, for example, In re Wrobel, 508 B.R. 271 (Bankr. W.D. N.Y. 2014) (construing

§ 522(o), mere pre-bankruptcy conversion of non-exempt to exempt property is not sufficient for limitation of state homestead).

Contrast In re Smither, 542 B.R. 39 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2015) (property was subject to reduction under section 522(o) to extent

attributable to fraudulent conversion from nonexempt to exempt). See also § 8:2 for discussion of prebankruptcy conversion

of assets.

The subsection is applied to limit a homestead only where there is actual intent to hinder, delay, or defraud. See In re Roberts,

527 B.R. 461 (Bankr. N.D. Fla. 2015); In re Corbett, 478 B.R. 62 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2012); In re Presto, 376 B.R. 554, 52 A.L.R.

Fed. 2d 689 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2007). The trustee or objecting creditor bears the burden of proving the fraudulent intent. In re

Coppaken, 572 B.R. 284 (Bankr. D. Kan. 2017) (judgment creditor satisfied burden of showing debtor's conversion of assets

with requisite fraudulent intent); In re Osejo, 447 B.R. 352 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2011) (trustee carried burden of showing intent

to hinder, delay, or defraud creditors); In re Agnew, 355 B.R. 276 (Bankr. D. Kan. 2006); see also In re Sissom, 366 B.R. 677

(Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2007) (discussing elements of proof on actual intent). The burden of proof is preponderance of evidence.

Wolters v. Lakey, 456 B.R. 687 (D. Kan. 2011); In re Cook, 460 B.R. 911 (Bankr. N.D. Fla. 2011). Construing section 522(o),

the court in In re Maronde, 332 B.R. 593, 55 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 51, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80394 (Bankr. D. Minn.

2005), stated some of the badges of fraud that the court may consider in passing on the debtor's intent to defraud a creditor:

1. the transfer or obligation was to an insider;

2. the debtor retained possession or control of the property transferred after the transfer;

3. the transfer or obligation was disclosed or concealed;

4. before the transfer was made or obligation was incurred, the debtor had been sued or threatened with suit;

5. the transfer was of substantially all of the debtor's assets;

6. the debtor absconded;

7. the debtor removed or concealed assets;

8. the value of the consideration received by the debtor was not reasonably equivalent to the value of the asset transferred or

the amount of the obligation incurred;

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

9. the debtor was insolvent or became insolvent shortly after the transfer was made or the obligation was incurred;

10. the transfer occurred shortly before or shortly after a substantial debt was incurred; and

11. the debtor transferred the essential assets of the business to a lienor was transferred the assets to an insider of the debtor.

Maronde, 332 B.R. at 600 (citing In re Northgate Computer Systems, Inc., 240 B.R. 328, 360–61 (Bankr. D. Minn. 1999)).

The Maronde court reduced the debtor's homestead but also used the finding of fraudulent intent as a basis to find lack of good

faith and denial of the Chapter 13 debtor's confirmation. See also In re Addison, 368 B.R. 791, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80889

(B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2007), aff'd in part, rev'd on other grounds in part, 540 F.3d 805, 60 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 299, Bankr.

L. Rep. (CCH) P 81298, 48 A.L.R. Fed. 2d 829 (8th Cir. 2008) (to determine whether debtor's eve of bankruptcy conversion

of assets was effected with intent to hinder, delay, or defraud creditors, bankruptcy court appropriately used badge-of-fraud

approach but erred in finding debtor's intent was such as to warrant the limitation of his exemption rights); In re Wilmoth,

397 B.R. 915, 61 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 463, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81373 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2008) (section 522(o) did

not change prior standard of determining fraudulent conversion of asset; it merely added 10-year look back); In re Lacounte,

342 B.R. 809, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80653 (Bankr. D. Mont. 2005).

In In re Booth, 417 B.R. 820 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2009), the court held that the debtor did not commit any acts with the intent to

hinder, delay, or defraud her creditors, therefore the Florida homestead exemption was allowed. The court stated:

None of the traditional badges of fraud are present. She fully and credibly explained her actions.

The Debtor lives a modest lifestyle and had no financial problems until her daughter defaulted on

the line of credit payments. She has no priority unsecured debts and she is current with her car

payments. Her credit card debt is modest. Her credit card billing statements and Schedules reflect

a history of responsible credit card use. She did not purchase luxury goods or take cash advances.

She consistently paid her credit card bills. The balance of her Chase credit card was $351.56 when

she incurred the home repair charges.

Even though the Debtor's income was decreasing in early 2009, her expenses were manageable. She

was able to cover the first mortgage, her car and credit card payments, and living expenses. Her

financial world collapsed with her daughter's disclosure of the line of credit default. The default

was the tipping point, turning the Debtor's manageable financial situation to unmanageable. The

Palmetto Road debt spiraled out of control. The economic crash made her situation desperate.

Her business dwindled and Palmetto Road depreciated. The Debtor panicked. She made the best

decisions she could under tremendous financial stress and without the benefit of comprehensive

professional advice.

In re Booth, 417 B.R. 820, 825 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2009).

The Tenth Circuit Bankruptcy Appellate Panel in In re Willcut, 472 B.R. 88, 67 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep.

(CCH) P 82272 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012), interpreted the statute's phrase “value of an interest in … real property” to refer to “the

measure of the increase in monetary value of the economic interest in real property claimed as a homestead due to a fraudulent

transfer of non-exempt funds into the property, rather than a title interpretation of the word ‘interest.’” In re Willcut, 472 B.R. 88,

67 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82272 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012). The BAP found no indication that

Congress intended to change the view that “mere conversion of nonexempt property into exempt property, without fraudulent

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

intent, does not deprive the debtor of exemption rights in the converted property, … [with] the purpose of adding § 522(o) and §

522(p) in 2005 … to address the pre-BAPCPA ‘mansion loophole’ and to limit the value of homestead exemptions when there

is fraud. This leads to our interpretation of § 522(o)—that the statute was enacted to prevent the fraudulent attempt to build up

equity in a homestead.” In re Willcut, 472 B.R. 88, 67 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82272 (B.A.P.

10th Cir. 2012). When there is no equity in the homestead property, “there is no value subject to reduction.” In re Willcut, 472

B.R. 88, 67 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82272 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012). The BAP affirmed the

bankruptcy court's finding of no equity and overruling the trustee's objection to homestead exemption.

The Eighth Circuit Bankruptcy Appellate Panel stressed the importance of the word “attributable” in the statute, holding that

where a debtor's alleged fraudulent conversion of non-exempt assets was used to make improvements to the otherwise exempt

homestead, the homestead is not automatically reduced by the full amount spent on the improvements; rather, section 522(o)

requires a showing of the extent to which the improvements actually increased the value of the homestead attributable to the

conversion. In re Crabtree, 562 B.R. 749, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 83058 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2017). To prove this reduction, the

Court stated:

Where a debtor fraudulently converts nonexempt assets to make improvements to his homestead, a

bankruptcy court must therefore determine both the value of the debtor's interest in the homestead

with those improvements and the value of the debtor's interest in the homestead without those

improvements. In most such cases, the difference will be the value of the debtor's interest in the

homestead that is “attributable” to the improvements and thus the amount by which the value

of the debtor's interest in the homestead must be reduced. The amount the debtor spent on the

improvements is relevant only to the extent an appraiser might take it into account in valuing the

homestead with the improvements.

In re Crabtree, 562 B.R. at 753–754.

Assuming a reduction in homestead is established for purposes of section 522(o), the question then becomes how a trustee

realizes recovery of the reduction. The debtor may still have an exemption, but it is reduced under the statute to the extent

attributable to fraudulent disposition. However, if all proceeds attributable to property disposed of in the 10-year period were

tainted with fraudulent intent, the entire homestead exemption may be denied. See, e.g., In re Rensin, 600 B.R. 870 (Bankr. S.D.

Fla. 2019). The court in In re Colliau, 552 B.R. 158 (Bankr. W.D. Tex. 2016), agreed with another decision from its district,

holding that it would be appropriate to impose an equitable lien on the property, permitting the trustee to sell the property to

recover the amount of the reduced homestead exemption. The Colliau debtors had claimed exemption in 100% of the fair market

value, but that value was reduced by $11,156 under section 522(o), and the trustee would be allowed to sell the property to

recover $11,156, and the court concluded that it had authority to issue an equitable lien under section 105(a). The court gave

the debtors 90 days to satisfy the lien before the trustee could sell the property. See also In re Sissom, 366 B.R. 677 (Bankr.

S.D. Tex. 2007) (applying an equitable lien under section 522(o)).

Section 522(o) applies only to exemptions claimed under subsection (b)(3)(A) and not to those allowable under (b)(3)(B),

meaning that entirety or joint interests that are protected under state law are not subject to section 522(o)'s restrictions. In re

Hinton, 378 B.R. 371 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2007).

Although Florida had traditionally taken a liberal stance as to allowing its homestead exemption, courts in that state have held

that to the extent the Florida homestead conflicts with section 522(o), “by virtue of the Supremacy Clause, 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(o)

preempts Florida's constitutional homestead exemption.” In re Garcia, 2010 WL 2697020 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2010). Accord In

re Osejo, 447 B.R. 352 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2011).

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

$170,350 cap on increase in homestead value acquired within 1,215 days of petition—Section 522(p)

Subsection (p) limits the amount of the homestead that was acquired within 1,215 days of filing the bankruptcy petition. The

amount in the statute is subject to automatic adjustment every three years, under 11 U.S.C.A. § 104, and the most recent

adjustment took effect April 1, 2019. As will be discussed later, some controversy results from the language used in this

subsection, referring to “electing” state or local exemptions, a distinction from prior subsection (o), which simply refers to any

homestead exemption “for purposes” of section 522(b)(3)(A). Section 522(p) provides:

(p)(1) Except as provided in paragraph (2) of this subsection and sections 544 and 548, as a result of electing

under subsection (b)(3)(A) to exempt property under State or local law, a debtor may not exempt any amount of

interest that was acquired by the debtor during the 1215-day period preceding the date of the filing of the petition

that exceeds in the aggregate $170,350 in value in—

(A) real or personal property that the debtor or a dependent of the debtor uses as a residence;

(B) a cooperative that owns property that the debtor or a dependent of the debtor uses as a residence;

(C) a burial plot for the debtor or a dependent of the debtor; or

(D) real or personal property that the debtor or dependent of the debtor claims as a homestead.

(2)(A) The limitation under paragraph (1) shall not apply to an exemption claimed under subsection

(b)(3)(A) by a family farmer for the principal residence of such farmer.

(B) For purposes of paragraph (1), any amount of such interest does not include any interest

transferred from a debtor's previous principal residence (which was acquired prior to the beginning

of such 1215-day period) into the debtor's current principal residence, if the debtor's previous and

current residences are located in the same State.

Section 522(p) is concerned with an “interest” acquired by the debtor during the 1,215-day period preceding the filing of the

petition. The term “interest” has been interpreted to refer to equity in the homestead property, rather than title or ownership

interests. In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. 102 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2017); Parks v. Anderson, 406 B.R. 79, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH)

P 81492 (D. Kan. 2009); see also In re Willcut, 472 B.R. 88, 67 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH)

P 82272 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012), agreeing with the Parks interpretation of “interest” and applying it in section 522(o). The

Meguerditchian Court found that the word “interest” appears in subsections (p)(1) and (p)(2)(B), and while not “expressly

defined” in the statute, in section 541(a)(1) it is clear that the “interests of the debtor in property” of the bankruptcy estate

can be “solely equitable in nature.” In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 109. That Court further concluded that section 522(p)

(1)'s reference to “interest” is in the context of “something quantifiable,” with a focus of economic value, “and there is nothing

unusual about speaking of an ‘amount of’ equity.” In contrast, “it would be strange to speak of someone having an ‘amount

of’ title, so title sits uneasily with subsection (p)(1) in this respect.” In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 110. Going further,

that Court found subsection (p)(2)(B)'s reference to transfer of an “interest” from one residence to another to “rule out any

definition of ‘amount of interest’ that reduces it to title.” Equity in one residence can be transferred to another, but title in one

residence cannot be transferred into another residence. In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 110. That court also found that “the

majority position is by far the more persuasive, that ‘interest’ in § 522(p) is plain in meaning and can only mean equity.” In

re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 110.

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

Other courts have adopted a “title” interpretation of “interest.” See cases cited in In re Willcut, 472 B.R. 88, 67 Collier Bankr.

Cas. 2d (MB) 1636, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82272 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012), and see discussion below of interpretations of

acquisition of the “interest.”

If the debtor acquired the interest prior to the 1,215-day period, subsection (p) does not apply. While it may appear

straightforward, application of the statute depends upon the facts and underlying state law. For example, the term “acquired”

was interpreted by one court applying Minnesota law to mean that delivery of a deed and the debtor's acquisition of the property

occurred when the conveying father instructed his attorney to record the deed, not at the time of the father's execution of the

deed. Since the deed was recorded within the 1215-day period, section 522(p) applied. In re Bruess, 539 B.R. 560 (B.A.P. 8th

Cir. 2015).

Section 522(p) was applied to limit the debtor's homestead where:

• The debtor partitioned community property with fraudulent intent to avoid the cap of section 522(p), resulting in the non-

debtor spouse being limited to what she could recover under the debtor's capped homestead. Matter of Wiggains, 848 F.3d

655, 77 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 511 (5th Cir. 2017).

• The debtor had lived in the home for more than a decade prior to the petition date but only acquired legal title within 1,215

days of the petition date. In re Aroesty, 385 B.R. 1, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81216 (B.A.P. 1st Cir. 2008). But compare In

re Peake, 480 B.R. 367 (Bankr. D. Kan. 2012)(distinguishing Aroesty).

• The debtor acquired the property more than 1,215 days prior to commencement of the bankruptcy case, but, less than three

months before filing for bankruptcy, converted nonexempt assets of $240,000 to pay the mortgagee significantly increasing

the equity in the residence. Parks v. Anderson, 406 B.R. 79, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81492 (D. Kan. 2009).

• The debtor acquired the interest in his residence, within section 522(p)'s meaning, when he conveyed the property to a trust

of which he was the trustee. In re Stella, 470 B.R. 1 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2012).

• The debtor acquired the property more than 1,215 days prepetition but only began to use it as a homestead within the 1,215

days. However, on appeal, the court reversed, holding that debtor's acquisition of ownership interest outside of 1,215-day

period protected his homestead exemption from monetary cap. In re Greene, 346 B.R. 835, 56 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB)

627, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80798 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2006), subsequently aff'd in part, rev'd on other grounds in part, 583

F.3d 614, 62 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 829, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81596 (9th Cir. 2009).

• The spouses transferred homestead property between themselves within 1,215 days, with fact that they continually resided

there not overcoming effect of transfer. In re Gentile, 483 B.R. 50 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2012).

• The debtors acquired the property within section 522(p)'s coverage when the prior conveyance was in fraud of creditors, and

re-conveyance was within statutory time period. In re Dickey, 517 B.R. 5 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2014).

Section 522(p) was not applied to limit the debtor's homestead where:

• Under Nevada law, the debtor had sufficient beneficial and equitable interest in the property as homestead prior to transfer of

legal title within the 1215 days from a limited liability company, so that section 522(p)(1) did not apply. In re Caldwell, 545

B.R. 605, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82932 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 2016).

• Section 522(p) was a limitation on the debtor's homestead exemption but did not convert a pre-bankruptcy unenforceable

judgment lien, under Texas law, into an enforceable lien against the homestead. In re McCombs, 659 F.3d 503, 66 Collier

Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 873, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 82086 (5th Cir. 2011).

• The debtor had inherited the property more than 1,215 days prepetition, although she had begun to occupy the property as a

homestead within the 1,215-day period. In re Rogers, 513 F.3d 212, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81081 (5th Cir. 2008).

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

• The objecting creditor failed to prove that the debtor acquired an interest in the homestead within 1,215 days before filing

bankruptcy. In re Migell, 569 B.R. 918 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2017).

• The trustee failed to prove that the debtor acquired equity in the homestead in excess of section 522(p)'s cap. In re Schreiber,

466 B.R. 903 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2012).

• The debtor acquired the property more than 1,215 days prior to commencement of the bankruptcy case, although the debtor

did not designate the property as a homestead until within the 1,215-day look-back period. In re Reinhard, 377 B.R. 315

(Bankr. N.D. Fla. 2007).

• The debtor acquired the property more than 1,215 days prior to commencement of the bankruptcy case, although the debtor

did not establish residency by moving a recreational vehicle and tent onto the property until within 1,215-day period. In re

Greene, 583 F.3d 614, 62 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 829, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81596 (9th Cir. 2009).

• The debtor moved from a larger to a smaller home the debtor already owned. In re Jones, 397 B.R. 765 (Bankr. D. S.C. 2008).

• Under Kansas law, debtor may claim residential exemption in equitable interest in land, and transfer of legal title to self-

settled trust and subsequent transfer back to debtor within 1,215 days did not trigger section 522(p). In re Peake, 480 B.R.

367 (Bankr. D. Kan. 2012) (distinguishing In re Aroesty, 385 B.R. 1, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81216 (B.A.P. 1st Cir. 2008),

based on difference in Massachusetts and Kansas law).

Another question under section 522(p) is whether the term “interest acquired” includes equity that accrues on the homestead

within the 1,215 days. In re Blair, 334 B.R. 374, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80415 (Bankr. N.D. Tex. 2005), considered this,

distinguished “equity” from “interest,” and held that subsection 522(p) does not apply to equity gained as a result of appreciation

within the 1,215-day period; see also In re Sainlar, 344 B.R. 669, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80712 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2006)

(same). In Blair, the Chapter 7 debtors also continued to make mortgage payments while the case was pending, improving the

equity value. These courts essentially found “interest” to mean an ownership interest, not the accumulation of equity gained

after ownership was acquired; since the ownership was acquired outside the 1,215-day period, section 522(p) was not triggered.

In what may foretell more case authority on this subject, another court concluded that the statute's term “interest” did encompass

equity acquired during the 1,215-day period. In re Rasmussen, 349 B.R. 747 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2006). In Rasmussen, the court's

analysis focused on the term “acquired by the debtor,” concluding that what the statute contemplated was the debtor's acquisition

of an interest by active means, including purchase, making a down payment, or paying down a mortgage. In contrast to these

“active” acquisitions, accumulating equity is, according to that court, a “passive” acquisition, and the court held that appreciation

of equity by mere increase in market value was not an acquisition “by the debtor.” While this is a thoughtful distinction, in an

appropriate cases, it could be argued that a debtor acquired equity by knowingly, “actively” purchasing property, albeit outside

that 1,215-day period, that the debtor knew would increase substantially in value, including during the 1,215 days. To find

a debtor's “active” role in gaining equity may not be that difficult in the right case, and it is predictable that the Rasmussen

rationale will be seen in new attacks by trustees on homesteads with equity issues. See In re Chouinard, 358 B.R. 814 (Bankr.

M.D. Fla. 2006) (following Rasmussen's passive market increase approach). The Fifth Circuit avoided adoption of a strict

“title” or “equity” approach to section 522(p), holding that the debtor's Texas homestead exemption was limited by that statute

when proof established that appreciation in value to the property within the 1,215 days pre-bankruptcy was attributed to actual

improvements to the property, constituting “actively acquired home equity.” In re Fehmel, 372 Fed. Appx. 507 (5th Cir. 2010).

In the Meguerditchian case, discussed above in the context of “equity,” a trustee argued that section 522(p)'s cap should apply

when it was alleged that the debtor acquired “equity” within the 1,215 days by rolling over the proceeds from sale of a previous

residence to pay down a mortgage on the present homestead. The court concluded that section 522(p)(2)(B) protected this type

of acquisition of equity, excluding from the statutory cap such amount of interest “transferred from a debtor's previous principal

residence into the debtor's current principal residence. Notably, this subsection requires only a transfer ‘into the debtor's current

principal residence’; it does not require that the transfer have funded the acquisition of the current form of title of the current

principle residence.” In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 116. That court found the only other case directly addressing the issue

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

to be In re Welch, 486 B.R. 1 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2013), and the Meguerditchian Court concluded that Welch “stands for the

proposition that a simple change in the form of title to equity that a debtor already owns is not an acquisition of interest within

the meaning of subsection (p)(1).” In re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 117. Although the issue was raised on appeal in In re Khan,

375 B.R. 5, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81024 (B.A.P. 1st Cir. 2007), the Meguerditchian Court found that it was not decided. In

re Meguerditchian, 566 B.R. at 117.

The same court that had decided Welch applied section 522(p)'s cap when a debtor actively acquired his entire equity ownership

within the 1,215 look-back period. In re Zakarian, 570 B.R. 680 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2017). In that case, the Chapter 7 debtor had

been the trustee of a trust of which his wife was beneficiary, with the debtor having no beneficial interest in the property under

that trust, but the trust conveyed the property to the spouses as tenants by entirety within the 1,215 days before the husband filed

bankruptcy. The court concluded that the debtor actively acquired his equity interest and his homestead exemption was capped.

It has been held that the trustee may not keep the case open to wait for the value of the homestead to appreciate in value so that

the trustee could potentially recover value above section 522(p)'s statutory cap. In re Colliau, 552 B.R. 158 (Bankr. W.D. Tex.

2016). That court held that the “snapshot rule,” which had been reaffirmed by the Fifth Circuit in In re Brown, 807 F.3d 701

(5th Cir. 2015), required that “exemptions are determined by the law and facts as they exist on the petition date and that they

do not change due to subsequent events.” Colliau, 552 B.R. at n. 24 (citing cases on “snapshot rule”).

Since some states have opted out of the federal exemption scheme and mandate the debtor's use of state law exemptions, while

other states permit the debtor to elect whether to claim exemptions under federal or state law, the question has arisen as to

whether subsections (p) and (q), which both use the term “electing,” apply both in opt-out states and in non-opt-out states. Most

courts agree that the cap on homesteads fixed by section 522(p) applies in every state, whether or not the state has opted out

of the federal exemptions. In In re Wayrynen, 332 B.R. 479, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80391 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2005), the court

held that the phrase in subsection (p), “as a result of electing under subsection (b)(3)(A) to exempt property under State or

local law,” could not be interpreted to make the provision applicable only to debtors in states where a debtor may elect between

federal and state schemes but not in states where the debtor has no choice other than the state scheme. “The gravamen of §

522(p)(1) is to limit the ability of individuals desiring to take advantage of the lenient exemption provisions of ‘debtor-friendly’

states by relocating to such states.” Wayrynen, 332 B.R. at 486. Again, in In re Virissimo, 332 B.R. 201 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2005),

the court held the provision to apply in both opt-out and non-opt-out states. Agreeing that the caps applied in opt-out states,

another court, in In re Summers, 344 B.R. 108 (Bankr. D. Ariz. 2006), held that the caps did not permit debtors to increase

the effective state-law homestead. See also In re Kaplan, 331 B.R. 483, 54 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1676 (Bankr. S.D.

Fla. 2005); In re Landahl, 338 B.R. 920, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80514 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2006); In re Kane, 336 B.R. 477,

55 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1148, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80492 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2006); In re Greene, 346 B.R. 835, 56

Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 627, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80798 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2006), subsequently aff'd in part, rev'd on

other grounds in part, 583 F.3d 614, 62 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 829, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81596 (9th Cir. 2009); In

re Rasmussen, 349 B.R. 747 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2006).

So far, in only one reported case has the court held that section 522(p)'s cap does not apply to debtors in opt-out states. In re

McNabb, 326 B.R. 785, 54 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 750, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80333 (Bankr. D. Ariz. 2005) (rejected by,

In re Rasmussen, 349 B.R. 747 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2006)). In this case, the court held that the Code's homestead cap applies only

in non-opt-out states. The court rather reluctantly found the statute's “plain meaning” of the phrase in subsection (p), “as a result

of electing under subsection (b)(3)(A) to exempt property under State or local law,” to compel the application of the statute

only to debtors who may choose between federal and state exemptions, not to debtors in states allowing only state exemptions.

In its criticism of the McNabb holding, the court in In re Kaplan, 331 B.R. 483, 54 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 1676 (Bankr.

S.D. Fla. 2005), noted that “[m]ore than two-thirds of the states have opted out of the federal exemptions and, if McNabb is

followed, these new caps would only apply in Texas and Minnesota, not in states like Arizona or Florida, in which debtors must

utilize state exemptions.” Kaplan, 331 B.R. at 484.

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 8

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

In view of the specific language “electing,” it is somewhat surprising that only the McNabb court reached this result. At this

point, no appellate court has spoken on the issue, which future editions of this manual will continue to follow. For further

examination of the new sections 522(o), (p), and (q), see Howard, Exemptions Under the 2005 Bankruptcy Amendments: A

Tale of Opportunity Lost, 79 Am. Bankr. L.J. 397, 402 (2005) (available on Westlaw).

The meaning of section 522(b)(1)'s “election” was an issue in In re Connor, 419 B.R. 304 (Bankr. E.D. N.C. 2009), discussed

previously in §§ 3:9 and 4:6. In Connor, the court held that when one joint debtor was not eligible for a state-law exemption,

but the other joint debtor was, the noneligible debtor was forced to use section 522(d) exemptions under section 522(b)(3)'s

domiciliary requirements; therefore, no “election” was made by that debtor, resulting in the husband and wife using different

exemption schemes. The Connor court did not discuss the McNabb or other court's discussion of election in the context of

section 522(p).

Since joint debtors are each entitled to their exemptions, joint debtors may stack their capped homestead exemptions. See In

re Nestlen, 441 B.R. 135, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 81915 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2010) (statutory cap of section 522(p) was doubled

in joint case filed by spouses); In re Limperis, 370 B.R. 859 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2007) (where the homestead exemption was

unlimited as to value under Florida law but was limited by the section 522(p) cap to $125,000 (now $170,350) as to each debtor

for residential property acquired during the 1,215-day period, joint Chapter 13 debtors' were entitled to stack their Florida

homestead exemptions in the maximum amount of $250,000).

$170,350 cap on homestead value where fraud or crime involved—Section 522(q)

Like subsection (p)'s reference to “electing” state or local exemptions, subsection (q) limits the amount of the homestead to

$170,350 if fraud or criminal activity was involved in its acquisition. The amount in the statute is subject to automatic adjustment

every three years, under 11 U.S.C.A. § 104, and the most recent adjustment took effect April 1, 2019. 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(q)

provides:

(q)(1) As a result of electing under subsection (b)(3)(A) to exempt property under State or local law, a debtor may

not exempt any amount of an interest in property described in subparagraphs (A), (B), (C), and (D) of subsection

(p)(1) which exceeds in the aggregate $170,350 if—

(A) the court determines, after notice and a hearing, that the debtor has been convicted of a felony (as defined in

section 3156 of title 18), which under the circumstances, demonstrates that the filing of the case was an abuse

of the provisions of this title; or

(B) the debtor owes a debt arising from—

(i) any violation of the Federal securities laws (as defined in section 3(a)(47) of the Securities Exchange Act

of 1934), any State securities laws, or any regulation or order issued under Federal securities laws or State

securities laws;

(ii) fraud, deceit, or manipulation in a fiduciary capacity or in connection with the purchase or sale of any

security registered under section 12 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 or under section 6 of

the Securities Act of 1933;

(iii) any civil remedy under section 1964 of title 18; or

(iv) any criminal act, intentional tort, or willful or reckless misconduct that caused serious physical injury or

death to another individual in the preceding five years.

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 9

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

(2) Paragraph (1) shall not apply to the extent the amount of an interest in property described in

subparagraphs (A), (B), (C), and (D) of subsection (p)(1) is reasonably necessary for the support of

the debtor and any dependent of the debtor.

One court has interpreted this subsection in the context of what is required to meet the “criminal act” element of section 522(q)(1)

(B)(iv). In re Larson, 340 B.R. 444, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 80511 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2006), opinion aff'd, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH)

P 80951, 2007 WL 1444093 (D. Mass. 2007), aff'd, 513 F.3d 325, 59 Collier Bankr. Cas. 2d (MB) 90, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH)

P 81109 (1st Cir. 2008). In Larson, the debtor had not been “convicted” in the sense of going to trial and having a jury verdict

of guilty; rather, the debtor had been involved in an automobile accident resulting in death of another driver. She was charged

with vehicular homicide, and she entered into a pretrial diversion under which she was placed on probation. The state judge

had, however, made findings sufficient to establish guilt of the vehicular homicide, for which a civil judgment had also been

entered in the amount of $1 million. The bankruptcy court determined that the state court findings were sufficient to constitute

a “criminal act” under section 522(q). A further hearing was required, however, to determine the extent to which the debtor

might need the claimed homestead in excess of the cap for her “reasonably necessary support.” 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(q)(2). For

interpretation of “reckless misconduct” see In re Burns, 395 B.R. 756 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2008). See also In re Bounds, 491 B.R.

440 (Bankr. W.D. Tex. 2013), concluding that proof of an increased amount reasonably necessary must be by preponderance

of evidence and finding that the debtor failed that burden.

The combination of the look-back period, the issues raised by extraterritorial use of state exemptions, and the possible

applications of subsections 522(o), (p), or (q) raise an unknown number of possible scenarios. To illustrate the difficulty of

determining the applicable law and the effect of these subsections, here is just an example of one of endless potential fact

variations:

A Tennessee businessman left his business partnership after a conflict with his former partners. This

conflict resulted in extensive litigation and the risk of a judgment in the amount of $5 million. The

businessman liquidated his real estate and other liquid assets in Tennessee where his homestead

exemption would be $5,000 (or $7,500 in a joint filing). The assets were liquidated after first

transferring them to his wife's name. They moved on January 1, 2005, to the state of Florida where

they acquired a home with $500,000 equity.

Assuming that the former business partners succeed in obtaining an overwhelming judgment, the debtor has several difficult

choices:

• If he files within two years (730 days) after moving his domicile to Florida, his homestead exemption will be capped at the

amount of the Tennessee limit ($5,000/$25,000). If Tennessee, like some states, prohibits nonresidents from using its rules,

he may be governed by the federal exemption scheme, with its $25,150 homestead. 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(d)(1).

• If he files more than two years but less than three years and four months (1,215 days) after acquiring the Florida home, the

(otherwise unlimited) Florida exemption will be capped at $170,350. 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(p).

• If he files more than 1,215 days after acquiring the house but within 10 years and if the value in the house can be found to

be attributable to the disposition of property with intent to hinder, delay, or defraud a creditor, all or such attributable part of

the homestead exemption may be set aside. 11 U.S.C.A. § 522(o).

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 10

§ 4:8.Homestead caps—Section 522(o), (p), and (q), Bankr. Exemption Manual § 4:8

Westlaw. © 2020 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

a0 United States Bankruptcy Judge, Western District of Tennessee

a1 of the Tennessee Bar

a2 of the Tennessee Bar

End of Document © 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government

Works.

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 11

You might also like

- How To File Your Own Bankruptcy: The Step-by-Step Handbook to Filing Your Own Bankruptcy PetitionFrom EverandHow To File Your Own Bankruptcy: The Step-by-Step Handbook to Filing Your Own Bankruptcy PetitionNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Harold P. WALTERS and Patricia A. Walters, His Wife, Debtors, v. United States National Bank in Johnstown, AppellantDocument6 pagesIn The Matter of Harold P. WALTERS and Patricia A. Walters, His Wife, Debtors, v. United States National Bank in Johnstown, AppellantScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Selected Chapter 13 Issues: Richard H. Thomson Clark & Washington, P.C. Atlanta, GeorgiaDocument11 pagesSelected Chapter 13 Issues: Richard H. Thomson Clark & Washington, P.C. Atlanta, Georgiabeluved2010No ratings yet

- How to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersFrom EverandHow to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- In Re Michael Duane MULLET, Debtor. First Bank of Colorado Springs, A State Banking Corporation, Appellant, v. Michael Duane MULLET, AppelleeDocument8 pagesIn Re Michael Duane MULLET, Debtor. First Bank of Colorado Springs, A State Banking Corporation, Appellant, v. Michael Duane MULLET, AppelleeScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- California Infrastructure Projects: Legal Aspects of Building in the Golden StateFrom EverandCalifornia Infrastructure Projects: Legal Aspects of Building in the Golden StateNo ratings yet

- In Re Budd George Belanger, Janice Leigh Belanger, Debtors. Home Owners Funding Corporation of America v. Budd George Belanger Janice Leigh Belanger, 962 F.2d 345, 4th Cir. (1992)Document6 pagesIn Re Budd George Belanger, Janice Leigh Belanger, Debtors. Home Owners Funding Corporation of America v. Budd George Belanger Janice Leigh Belanger, 962 F.2d 345, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 12 Collier Bankr - Cas.2d 630, Bankr. L. Rep. P 70,339 Birmingham Trust National Bank, A National Banking Association v. John P. Case, JR., 755 F.2d 1474, 11th Cir. (1985)Document5 pages12 Collier Bankr - Cas.2d 630, Bankr. L. Rep. P 70,339 Birmingham Trust National Bank, A National Banking Association v. John P. Case, JR., 755 F.2d 1474, 11th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reopening A Bankruptcy CaseDocument7 pagesReopening A Bankruptcy Case83jjmack100% (3)

- Shawmut Bank v. Goodrich, 1st Cir. (1993)Document19 pagesShawmut Bank v. Goodrich, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Riggs National Bank of Washington, D.C. v. John Gillis Perry, JR., in Re John Gillis Perry, JR., Debtor, 729 F.2d 982, 4th Cir. (1984)Document8 pagesRiggs National Bank of Washington, D.C. v. John Gillis Perry, JR., in Re John Gillis Perry, JR., Debtor, 729 F.2d 982, 4th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Preferential Transfers: A Focus On The 3rd CircuitDocument21 pagesPreferential Transfers: A Focus On The 3rd CircuitBrent Diefenderfer100% (1)

- Billy Dampier, Jr. v. United States Bankruptcy Court For The District of Colorado, 10th Cir. BAP (2017)Document13 pagesBilly Dampier, Jr. v. United States Bankruptcy Court For The District of Colorado, 10th Cir. BAP (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 14 Collier Bankr - Cas.2d 1215, Bankr. L. Rep. P 71,050 in Re Gerald T. Black and Denise B. Black, Debtors. Garth L. Driggs v. Gerald T. Black, 787 F.2d 503, 10th Cir. (1986)Document5 pages14 Collier Bankr - Cas.2d 1215, Bankr. L. Rep. P 71,050 in Re Gerald T. Black and Denise B. Black, Debtors. Garth L. Driggs v. Gerald T. Black, 787 F.2d 503, 10th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Jerry Daniel WILSONDocument5 pagesIn The Matter of Jerry Daniel WILSONScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Robert H. Clark, Debtor. Robert H. Clark v. Thomas J. O'neill, As Trustee. Robert H. Clark, 711 F.2d 21, 3rd Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesIn Re Robert H. Clark, Debtor. Robert H. Clark v. Thomas J. O'neill, As Trustee. Robert H. Clark, 711 F.2d 21, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The First Interstate Bank of Idaho v. The Small Business Administration and James C. Sanders, Administrator, Small Business Administration, 868 F.2d 340, 1st Cir. (1989)Document11 pagesThe First Interstate Bank of Idaho v. The Small Business Administration and James C. Sanders, Administrator, Small Business Administration, 868 F.2d 340, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilding v. Citifinancial Consum, 475 F.3d 428, 1st Cir. (2007)Document8 pagesWilding v. Citifinancial Consum, 475 F.3d 428, 1st Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New YorkDocument10 pagesUnited States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New YorkChapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- In Re David Larry Davis, Debtor. Charles A. Gower, Trustee v. Ford Motor Credit Company and Maxwell Ford Tractor, Inc., 734 F.2d 604, 11th Cir. (1984)Document6 pagesIn Re David Larry Davis, Debtor. Charles A. Gower, Trustee v. Ford Motor Credit Company and Maxwell Ford Tractor, Inc., 734 F.2d 604, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MERS Bankruptcy and IdahoDocument17 pagesMERS Bankruptcy and IdahoForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- USCOURTS TXWB 5 - 16 BK 51059 0Document11 pagesUSCOURTS TXWB 5 - 16 BK 51059 0NameNo ratings yet

- In Re Anastas 94 F.3d 1280Document11 pagesIn Re Anastas 94 F.3d 1280Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CLARK ET UX. v. RAMEKER, TRUSTEE, ET AL.Document13 pagesCLARK ET UX. v. RAMEKER, TRUSTEE, ET AL.ted5075No ratings yet

- In Re Randall Clark Burns and Deborah A. Burns, Debtors. Citizens National Bank v. Randall Clark Burns, 894 F.2d 361, 10th Cir. (1990)Document4 pagesIn Re Randall Clark Burns and Deborah A. Burns, Debtors. Citizens National Bank v. Randall Clark Burns, 894 F.2d 361, 10th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bankr. L. Rep. P 71,503 Chandler Bank of Lyons v. David Jay Ray and Jerold E. Berger, 804 F.2d 577, 10th Cir. (1986)Document4 pagesBankr. L. Rep. P 71,503 Chandler Bank of Lyons v. David Jay Ray and Jerold E. Berger, 804 F.2d 577, 10th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gary T. Napotnik v. Equibank and Parkvale Savings Association, 679 F.2d 316, 3rd Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesGary T. Napotnik v. Equibank and Parkvale Savings Association, 679 F.2d 316, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bankruptcy LawDocument17 pagesBankruptcy LawPP KPNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Roger Burnett Treadwell, Debtor. James D. Walker, JR., Trustee v. Roger Burnett Treadwell, and Regina Taylor, 699 F.2d 1050, 11th Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesIn The Matter of Roger Burnett Treadwell, Debtor. James D. Walker, JR., Trustee v. Roger Burnett Treadwell, and Regina Taylor, 699 F.2d 1050, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bank of Boston v. Burr, 160 F.3d 843, 1st Cir. (1998)Document10 pagesBank of Boston v. Burr, 160 F.3d 843, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Car Renovators, Debtors. Thomas E. Reynolds, Trustee of The Bankruptcy Estate of Car Renovators, Inc. v. Dixie Nissan, 946 F.2d 780, 11th Cir. (1991)Document6 pagesIn Re Car Renovators, Debtors. Thomas E. Reynolds, Trustee of The Bankruptcy Estate of Car Renovators, Inc. v. Dixie Nissan, 946 F.2d 780, 11th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Strickland, Response, Objection and Memo.Document9 pagesStrickland, Response, Objection and Memo.Ron HouchinsNo ratings yet

- Lowry Federal Credit Union, Creditor-Appellant v. James Dale West and Sharon Kay West, Debtors-Appellees, 882 F.2d 1543, 10th Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesLowry Federal Credit Union, Creditor-Appellant v. James Dale West and Sharon Kay West, Debtors-Appellees, 882 F.2d 1543, 10th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- C.W. Mining Company v. Bank of Utah, 10th Cir. (2014)Document9 pagesC.W. Mining Company v. Bank of Utah, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 4 - in Re Carbone Companies IncDocument5 pages4 - in Re Carbone Companies IncJun MaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Bank v. Dalton, 4th Cir. (2000)Document8 pagesConsolidated Bank v. Dalton, 4th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Remert 141 F.3d 277Document10 pagesIn Re Remert 141 F.3d 277Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- In Re C.A. Thurman, Debtor. McOrp Management Solutions, Inc. v. C.A. Thurman, 901 F.2d 839, 10th Cir. (1990)Document5 pagesIn Re C.A. Thurman, Debtor. McOrp Management Solutions, Inc. v. C.A. Thurman, 901 F.2d 839, 10th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rushton v. State Bank of South, 164 F.3d 1338, 10th Cir. (1999)Document11 pagesRushton v. State Bank of South, 164 F.3d 1338, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Preferential Payment AvoidanceDocument5 pagesPreferential Payment AvoidanceJun MaNo ratings yet

- In Re Andrew S. Bland and Sonia J. Bland, Debtors. Finance One v. Andrew S. Bland and Sonia J. Bland, 793 F.2d 1172, 11th Cir. (1986)Document7 pagesIn Re Andrew S. Bland and Sonia J. Bland, Debtors. Finance One v. Andrew S. Bland and Sonia J. Bland, 793 F.2d 1172, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kham & Nate's Shoes No. 2, Inc., Debtor-Appellee v. First Bank of Whiting, 908 F.2d 1351, 1st Cir. (1990)Document15 pagesKham & Nate's Shoes No. 2, Inc., Debtor-Appellee v. First Bank of Whiting, 908 F.2d 1351, 1st Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cordillera Golf Club, LLC Dba The Club at CordilleraDocument26 pagesCordillera Golf Club, LLC Dba The Club at CordilleraChapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- In Re BDT Farms, Inc., Debtor, John E. Foulston, United States Trustee, Region 20 v. BDT Farms, Inc., 21 F.3d 1019, 10th Cir. (1994)Document6 pagesIn Re BDT Farms, Inc., Debtor, John E. Foulston, United States Trustee, Region 20 v. BDT Farms, Inc., 21 F.3d 1019, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Union Bank v. Wolas, 502 U.S. 151 (1991)Document12 pagesUnion Bank v. Wolas, 502 U.S. 151 (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bankr. L. Rep. P 77,385 Robert D. MacY v. Anna Lowell MacY, 114 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesBankr. L. Rep. P 77,385 Robert D. MacY v. Anna Lowell MacY, 114 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Authority to Enforce Promissory Note Indorsed in BlankDocument22 pagesAuthority to Enforce Promissory Note Indorsed in BlankBeth Stoops Jacobson0% (1)

- SASCO LBHI OpinionDocument15 pagesSASCO LBHI OpinionDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- Cordillera Golf Club, LLC Club at Cordillera,: "Motion") "Debtor")Document49 pagesCordillera Golf Club, LLC Club at Cordillera,: "Motion") "Debtor")Chapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- Colombo Bank v. Sharp, 4th Cir. (2009)Document27 pagesColombo Bank v. Sharp, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Edwin Leo Vann, Debtor. City Bank & Trust Co. v. Edwin Leo Vann, 67 F.3d 277, 11th Cir. (1995)Document10 pagesIn Re Edwin Leo Vann, Debtor. City Bank & Trust Co. v. Edwin Leo Vann, 67 F.3d 277, 11th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dominion Bank of The Cumberlands, Na v. James R. Nuckolls Judy M. Nuckolls, 780 F.2d 408, 4th Cir. (1985)Document16 pagesDominion Bank of The Cumberlands, Na v. James R. Nuckolls Judy M. Nuckolls, 780 F.2d 408, 4th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rake v. Wade, 508 U.S. 464 (1993)Document10 pagesRake v. Wade, 508 U.S. 464 (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Exhibits in Civil Cases - New York City Accident Attorney GGCRBHS&MDocument10 pagesIntroduction of Exhibits in Civil Cases - New York City Accident Attorney GGCRBHS&Madfsh-1No ratings yet

- NPL BiblioDocument23 pagesNPL Biblioadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Confirmation NoticeDocument1 pageConfirmation Noticeadfsh-1No ratings yet

- 2022 Can LIIDocs 3318Document10 pages2022 Can LIIDocs 3318adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Bouvier Law Dictionary Knowledge (Know or Knowing or KNDocument2 pagesBouvier Law Dictionary Knowledge (Know or Knowing or KNadfsh-1No ratings yet

- RC 2119Document3 pagesRC 2119adfsh-1No ratings yet

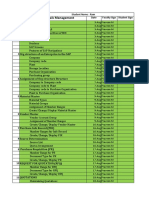

- Billing: Spreadsheet - XlisxDocument1 pageBilling: Spreadsheet - Xlisxadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Lex-Nex Intent Fy20Document2 pagesLex-Nex Intent Fy20adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Ahmed v. Morgans Hotel Group Mgt. - LLC - 2017 N.Y. Misc PDFDocument6 pagesAhmed v. Morgans Hotel Group Mgt. - LLC - 2017 N.Y. Misc PDFadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Panel 1Document76 pagesPanel 1adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Employment/W: PullingDocument2 pagesEmployment/W: Pullingadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Stays in Civil Appeals: Clerk of The Court, New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division Fourth Department RochesterDocument6 pagesStays in Civil Appeals: Clerk of The Court, New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division Fourth Department Rochesteradfsh-1No ratings yet

- Checklist Registrant Other Cons Equip Pre-Permit-2Document1 pageChecklist Registrant Other Cons Equip Pre-Permit-2adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Clarifying PEO Arrangement QuestionsDocument2 pagesClarifying PEO Arrangement Questionsadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Checklist Registrant Other Cons Equip CompletionDocument1 pageChecklist Registrant Other Cons Equip Completionadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Checklist Registrant Other Cons Equip On-Going ProjectDocument1 pageChecklist Registrant Other Cons Equip On-Going Projectadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Prevailing Wage Requirements in New YorkDocument55 pagesPrevailing Wage Requirements in New Yorkadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Appellate 2719 BakerDocument48 pagesAppellate 2719 Bakeradfsh-1No ratings yet

- Checklist Registrant CF CompletionDocument1 pageChecklist Registrant CF Completionadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Annual Report of The NYS Labor Relations BD 1947Document150 pagesAnnual Report of The NYS Labor Relations BD 1947adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Contractor GuideDocument2 pagesContractor Guideadfsh-1No ratings yet

- PR 08 157Document15 pagesPR 08 157adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Labor Market Information Handbook FOR Oc Cupational Planners and Administrators INDocument353 pagesLabor Market Information Handbook FOR Oc Cupational Planners and Administrators INadfsh-1No ratings yet

- Ia116 3Document2 pagesIa116 3adfsh-1No ratings yet

- PR 11 180Document6 pagesPR 11 180adfsh-1No ratings yet

- Part 222 - Hauling of Aggregate Supply Construction Materials 222.1 DefinitionsDocument1 pagePart 222 - Hauling of Aggregate Supply Construction Materials 222.1 Definitionsadfsh-1No ratings yet

- The Jobseeker 1989Document93 pagesThe Jobseeker 1989adfsh-1No ratings yet

- PR 07035Document9 pagesPR 07035adfsh-1No ratings yet

- PR 09 127Document17 pagesPR 09 127adfsh-1No ratings yet

- PR 07014Document7 pagesPR 07014adfsh-1No ratings yet

- NHBC Standards 2011 Bre SD 1 SRCDocument5 pagesNHBC Standards 2011 Bre SD 1 SRCSuresh RaoNo ratings yet

- Hedonomics: Bridging Decision Research With Happiness ResearchDocument20 pagesHedonomics: Bridging Decision Research With Happiness ResearchgumelarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tentang Akuntansi Dengan Metode Kualitatif IDocument8 pagesJurnal Tentang Akuntansi Dengan Metode Kualitatif IAfni FebrianaNo ratings yet

- Discharging A ClientDocument6 pagesDischarging A ClientNorman Batalla Juruena, DHCM, PhD, RNNo ratings yet

- Proximate Cause ExplainedDocument3 pagesProximate Cause ExplainedJoanne BayyaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Plasticity: Dong Phill Jang, Piemaan Fazily, Jeong Whan YoonDocument17 pagesInternational Journal of Plasticity: Dong Phill Jang, Piemaan Fazily, Jeong Whan YoonGURUDAS KARNo ratings yet

- IB Urban Environments Option G (Latest 2024)Document154 pagesIB Urban Environments Option G (Latest 2024)Pasta SempaNo ratings yet

- S Sss 001Document4 pagesS Sss 001andy175No ratings yet

- KEDIT User's GuideDocument294 pagesKEDIT User's GuidezamNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Analysis - Certified Reference Material: Cetyl PalmitateDocument6 pagesCertificate of Analysis - Certified Reference Material: Cetyl PalmitateRachel McArdleNo ratings yet

- Technical Data About The Production of Steel StructuresDocument2 pagesTechnical Data About The Production of Steel StructuresPress EscapeNo ratings yet

- Engine Tune-UpDocument43 pagesEngine Tune-UpЮра ПетренкоNo ratings yet

- Personal Styling Service-Contract - No WatermarkDocument5 pagesPersonal Styling Service-Contract - No WatermarkLexine Emille100% (1)

- Procedures For Drill String Design Engineering EssayDocument16 pagesProcedures For Drill String Design Engineering EssayGerardy Cantuta AruniNo ratings yet

- National Electrification Administration Vs GonzagaDocument1 pageNational Electrification Administration Vs GonzagaDonna Amethyst BernardoNo ratings yet

- Digital Undated Portrait Cosy MondayDocument133 pagesDigital Undated Portrait Cosy MondayholajackNo ratings yet

- IBM OpenPages Admin Guide 7.0 PDFDocument822 pagesIBM OpenPages Admin Guide 7.0 PDFMba NaniNo ratings yet

- Subhasis Patra CV V3Document5 pagesSubhasis Patra CV V3Shubh SahooNo ratings yet

- Ram SAP MM Class StatuscssDocument15 pagesRam SAP MM Class StatuscssAll rounderzNo ratings yet

- SDA HLD Template v1.3Document49 pagesSDA HLD Template v1.3Samuel TesfayeNo ratings yet

- Case Study - NISSANDocument5 pagesCase Study - NISSANChristy BuiNo ratings yet

- Sample BudgetDocument109 pagesSample BudgetAnjannette SantosNo ratings yet

- Systemverilog Interview QuestionsDocument31 pagesSystemverilog Interview QuestionsDivya Dm100% (1)

- Gliffy Public Diagram - ATM FlowchartDocument3 pagesGliffy Public Diagram - ATM Flowchartmy nNo ratings yet

- Zodiac Working Boat MK6HDDocument4 pagesZodiac Working Boat MK6HDdan antonNo ratings yet

- Seed FilesDocument1 pageSeed Filesارسلان علیNo ratings yet

- People v. ChuaDocument1 pagePeople v. ChuaErnie Gultiano100% (1)

- SRX835 Spec Sheet - 11 - 11 - 19Document4 pagesSRX835 Spec Sheet - 11 - 11 - 19Eric PageNo ratings yet

- Government's Role in Public HealthDocument2 pagesGovernment's Role in Public Healthmrskiller patchNo ratings yet

- Buffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorFrom EverandBuffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- IFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASFrom EverandIFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- Getting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorFrom EverandGetting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- How to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseFrom EverandHow to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseNo ratings yet

- The Business Legal Lifecycle US Edition: How To Successfully Navigate Your Way From Start Up To SuccessFrom EverandThe Business Legal Lifecycle US Edition: How To Successfully Navigate Your Way From Start Up To SuccessNo ratings yet

- Disloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpFrom EverandDisloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (214)

- Wall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementFrom EverandWall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- Learn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysFrom EverandLearn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- AI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersFrom EverandAI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersNo ratings yet

- How to Structure Your Business for Success: Choosing the Correct Legal Structure for Your BusinessFrom EverandHow to Structure Your Business for Success: Choosing the Correct Legal Structure for Your BusinessNo ratings yet

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (24)

- The Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesFrom EverandThe Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Legal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessFrom EverandLegal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the PublicFrom EverandThe Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the PublicRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Competition and Antitrust Law: A Very Short IntroductionFrom EverandCompetition and Antitrust Law: A Very Short IntroductionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- LLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessFrom EverandLLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Building Your Empire: Achieve Financial Freedom with Passive IncomeFrom EverandBuilding Your Empire: Achieve Financial Freedom with Passive IncomeNo ratings yet