Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Visceral Leishmania-IDU Presentation

Uploaded by

Fran Camilleri0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views26 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views26 pagesVisceral Leishmania-IDU Presentation

Uploaded by

Fran CamilleriCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 26

A neglected cause of lymphadenopathy

Case

59 year old male who is a known case of HIV and previously

treated for visceral leishmaniasis. Presented to HIV clinic for

routine check up, with the main complaint of generalised

lethargy.

• On examination

– cervical and inguinal lymphadenopathy

•approximately 2cm in size in both areas

•hepatosplenomegaly: distended but soft and non tender

• Also of note was a recent weight loss and a long-standing dry cough

• No reported fever or night sweats

• No other positive findings were of note

• Drug History

– Symtuza

– NKDA

Patient was directly admitted for further investigations

– US guided lymph node biopsy

– CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis

– Bone marrow aspiration

Pancytopenia was also noted in his blood work

– WCC 1.02

– Neutrophils 0.58

– Platelets 57

– Hb 7

2 units of RCC were subsequently transfused after which Hb was

still 7.7 and another unit of RCC was transfused.

In view of his past history of visceral leishmania and the tell tale signs

and symptoms he was exhibiting, patient was started on

Amphotericin B.

CT Abdomen & Pelvis

• Thorax:

– 10mm nodule in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe

– Enlarged lymph nodes in anterior mediastinum, supradiaphramatically

– Circumferential wall thickening of distal oesophagus with few surrounding lymph

nodes

• Abdomen

– Hepatosplenomegaly with hypodense lesions within both structures

– Dilated portal and hepatic veins

– Moderate ascites

– Liver hilar, perigastric, coeliac, mesenteric, aortocaval and bilateral inguinal

lymphadenopathy

– Cholecyctitis- 2 calculi in gallbladder neck

US guided biopsy:

Biopsy of enlarged lymph node in the left groin

– granulomatous infiltrate accompanied by lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Numerous leishmania amastigotes with no evidence of neoplasia.

Bone marrow aspiration:

Decreased iron stores with no ring sideroblasts, very few fragments present.

Marrow is heavily infiltrated by Leishman Donovan bodies

Leishmania Spp PCR Urine:

Detected

As the diagnosis was now re-confirmed, the patient was

thus continued on Amphotericin B with appointments to

continue treatment in hospital as an outpatient.

Case planned to be discussed at MDT meeting in view of

multiple findings on CT TAP

Leishmaniasis

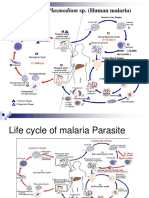

• 3 main forms of leishmaniases:

– visceral (commonly fatal without treatment)

– cutaneous (the most common, usually causing skin ulcers)

– mucocutaneous (affecting mouth, nose and throat)

• The protozoan parasites causing Leishmaniasis are transmitted by the bite of

infected sandfly

• The disease is associated with malnutrition, population displacement, poor

housing and immunosuppression.

• An estimated 700 000 to 1 million new cases occur annually

•Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a zoonotic vector-borne

disease caused by the Leishmania donovani protozoa

complex

•Highly endemic in Iran, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.

Common in the tropics, subtropics, and the Mediterranean.

•Complex parasite–host interactions, predispose certain

individuals to developing the disease or to controlling the

infection hence influencing a spectrum of clinical

manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to fatal visceral

infections.

In non-endemic areas, VL is mostly opportunistic, with up to

70% adult cases related to HIV co-infection. The greatest

prevalence of co-infection in non-endemic areas is in the

Mediterranean area. Atypical presentations of VL are reported

in HIV patients (WHO, 2007).

The numbers of leishmaniasis cases are increasing worldwide

due to:

• lack of vaccines

• difficulties in controlling vectors

• increasing number of parasites resistance to chemotherapy.

Clinical Presentation

• Fever & night sweats

• Weight loss

• Hepatosplenomegaly

• Pancytopenia

• Hypergammaglobulinemia

• Skin darkening

Patients typically appear cachectic with abdominal

distention due to massive hepatospenomegaly. Jaundice

is rarely seen and is considered a bad prognosticator.

In the immunosuppressed:

• gastrointestinal and respiratory involvement

Investigations

• Parasites can be detected through direct evidence in the form of amastigotes

(differentiated promastigotes in the phagosome) in tissue; from peripheral

blood, bone marrow, liver or splenic aspirates

• Immunodiagnostic serologic tests

– Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test, which is 80-100% sensitive in

patients who are not co-infected with HIV.

– ELISA can be combined with IFA and Western blot to increase sensitivity

and specificity. PCR is being used more frequently; it is more accurate in

determining new-onset leishmaniasis as compared to serum tests (92-99%

sensitivity; 100% specificity)

– Serologic tests such as isoenzyme or monoclonal antibody analysis are not

well established.

Investigations: Routine Labs

• CBC:

– normocytic, normochromic anaemia

– leukopenia; reduced neutrophils, monocytosis and lymphocytosis

– thrombocytopenia

• LFT:

– mild increase in ALP, AST and ALT

• Hypogammaglobulinemia, immune complexes and rheumatoid

factors are present in most patients

• Definitive diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis requires organ aspiration and

microscopic examination of tissue specimens.

• Noninvasive diagnosis by strip test detection of anti-K39 immunoglobulin (Ig)

G antibody in blood specimens obtained by fingerstick is available

• For active case detection, the recombinant K39 immunochromatographic test

(rK39 ICT) offers a simple, non-invasive and accurate test with increased

patient compliance. Reliable tests are also required to estimate actual disease

burden, track disease trends over time, improve diagnosis-treatment

algorithms and to verify disease elimination within communities

Management

Leishmaniasis is a somewhat neglected tropical disease in terms of drug

discovery and development.

Several drugs, differing in their cost, toxicity, treatment duration and

emergence of drug resistance, are used for different types of

leishmaniasis.

Recent improvements have been achieved by combination therapy,

reducing the time and cost of treatment. Nonetheless, new drugs are

still urgently needed.

Management

Treatment approach depends on host and parasite factors

•Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®), which is

administered by IV infusion

•Oral agent miltefosine for treatment of cutaneous, mucosal,

and visceral leishmaniasis caused by particular Leishmania

species

Lipid formulations of Amphotericin B

improve its bioavailability and

pharmacokinetics whilst also reducing side

effects. The lipid molecules are rapidly

assimilated by hepatic macrophages, where

the parasite accumulates. Another

advantage is that smaller liposomes stay in

the blood stream longer than the free drug.

The main limitations are its high cost,

administration route and lack of stability at

high temperature.

Adapted from Visceral leishmaniasis treatment: What do we have, what do we need and how to deliver it? Freitas-Junior et al.

2012

Management

• Until now, the recommendation for treatment of a VL episode in an

HIV co-infected patient was first to consider lipid formulations of

amphotericin B, infused at a dose of 3–5 mg/kg daily or in 10

intermittent doses (on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31 and 38) to a total dose

of 40 mg/kg.

• Evidence from clinical trials on the efficacy of combination therapy

(liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB) plus miltefosine) to treat VL in

HIV co-infected patients instead of monotherapy has offered new

possibilities for case management.

• Immunosuppression is a risk factor for VL and can alter disease

presentation and management.

• Leishmania with HIV coinfection has several characteristic features:

– lower cure rates

– higher rates of drug toxicity

– higher relapse and mortality rates

• Use of an effective systemic therapy is important, as is supportive

care: therapy for malnutrition, anemia/bleeding, and intercurrent

infections. Antiretroviral therapy should be started or optimized;

appropriate use of ART may delay relapses and improve survival.

HIV infection and leishmaniasis share an immunopathological pathway

that enhances replication of both pathogens and accelerates the

progression of both VL and HIV (Tremblay et al., 1996; Alvar et al., 2008; Mock et al., 2012)

Prevention

• No vaccines or drugs available for prevention

• The best way for travelers and susceptible people to prevent infection

is to protect themselves from sand fly bites.

– Personal protective measures include:

•minimizing nocturnal outdoor activities

•wearing protective clothing

•applying insect repellent to exposed skin

• Prevention measures must be tailored to the local setting and typically

are difficult to sustain. Control measures against sand fly vectors or

animal reservoir hosts might be effective in some settings

References

• Ramos et al. Is Visceral Leishmaniasis Different in Immunocompromised Patients Without Human

Immunodeficiency Virus? A Comparative, Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2017 Oct;97(4):1127-1133. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0940. Epub 2017 Oct 10. PMID: 29016284; PMCID:

PMC5637592.

• Sundar et al. Noninvasive Management of Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis: Clinical Application of Diagnosis by

K39 Antigen Strip Testing at a Kala-azar Referral Unit. Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 35, Issue 5, 1

September 2002, Pages 581–586

• Singh O.P., Sundar S. Developments in diagnosis of visceral Leishmaniasis in the elimination era. J. Parasitol.

Res., 2015 (2015), p. 239469

• Lucio H. Freitas-Junior, Eric Chatelain, Helena Andrade Kim, Jair L. Siqueira-Neto. Visceral leishmaniasis

treatment: What do we have, what do we need and how to deliver it? International Journal for Parasitology:

Drugs and Drug Resistance 2 (2012) 11-19

THANK YOU

You might also like

- Gastroenterology For General SurgeonsFrom EverandGastroenterology For General SurgeonsMatthias W. WichmannNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphocytic LeukemiaDocument8 pagesAcute Lymphocytic LeukemiaWendy EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Fever, Hepatosplenomegaly, and Pancytopenia in A 46-Year-Old WomanDocument6 pagesProlonged Fever, Hepatosplenomegaly, and Pancytopenia in A 46-Year-Old WomanFerdy AlviandoNo ratings yet

- Case 13-2008-Rheum Arthritis, LymphadenopathyDocument59 pagesCase 13-2008-Rheum Arthritis, Lymphadenopathypalak32No ratings yet

- Medicine Seminar Combined-1Document30 pagesMedicine Seminar Combined-1Deepanshu KumarNo ratings yet

- An Sell 2005Document11 pagesAn Sell 2005Rachel AutranNo ratings yet

- Lymphoma and HIVDocument20 pagesLymphoma and HIVALEX NAPOLEON CASTA�EDA SABOGAL100% (1)

- Malignancy DR RashaDocument29 pagesMalignancy DR RashaRasha TelebNo ratings yet

- Hodgkins Lymphoma: DR - Vaijanath DugganikarDocument22 pagesHodgkins Lymphoma: DR - Vaijanath Dugganikararjun_paulNo ratings yet

- 7-IV Pathology and Management of Periodontal Problems in Patients With Hiv InfectionsDocument35 pages7-IV Pathology and Management of Periodontal Problems in Patients With Hiv InfectionsSamridhi SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Non Hodgin's LymphomaDocument27 pagesNon Hodgin's LymphomaJeevitha VanithaNo ratings yet

- Hodgkin's LymphomaDocument21 pagesHodgkin's LymphomaRavi K N100% (1)

- Leukopenia and Bone Marrow TransplantationDocument20 pagesLeukopenia and Bone Marrow Transplantationdhanya jayanNo ratings yet

- Lymphomas: Reported by J.P. Calibuso, S.M.Macapugay, M.G.Malihan, J.C.RuedaDocument32 pagesLymphomas: Reported by J.P. Calibuso, S.M.Macapugay, M.G.Malihan, J.C.RuedaRui Si GbNo ratings yet

- DR Anil Sabharwal MDDocument57 pagesDR Anil Sabharwal MDsaump3No ratings yet

- LymphomaDocument40 pagesLymphomaMans Fans100% (1)

- Conditions of The Lymph SystemDocument37 pagesConditions of The Lymph Systemkurage_07No ratings yet

- Lymphadenopathy: Clinical ApproachDocument31 pagesLymphadenopathy: Clinical ApproachPooja ShashidharanNo ratings yet

- View Media GalleryDocument9 pagesView Media GallerynandaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Glomerular Disease: C.M. Yuan Nephrology SVC Walter Reed Army Medical Center Washington, DC 20307Document40 pagesUnderstanding Glomerular Disease: C.M. Yuan Nephrology SVC Walter Reed Army Medical Center Washington, DC 20307mondy199646No ratings yet

- AIDS and PeriodontiumDocument25 pagesAIDS and PeriodontiumPathivada LumbiniNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Lymphoscintigraphy ForDocument4 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Lymphoscintigraphy ForMARIA FLAVIA MACEDO PÉREZNo ratings yet

- LymphomasDocument34 pagesLymphomasanimesh vaidyaNo ratings yet

- Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)Document55 pagesFever of Unknown Origin (FUO)mohamed hanyNo ratings yet

- 74 Year Old Woman With Fatigue, Anorexia, and AbdoDocument6 pages74 Year Old Woman With Fatigue, Anorexia, and AbdoRamiro Arraya MierNo ratings yet

- Lymphoma in Children: DR Sunil JondhaleDocument42 pagesLymphoma in Children: DR Sunil JondhaleSunjon JondhleNo ratings yet

- Lymphoma (Hodgkin's Disease andDocument20 pagesLymphoma (Hodgkin's Disease andKulgaurav RegmiNo ratings yet

- Af13e6df 9c91 4284 A3ae Feb2bacbcba4Document7 pagesAf13e6df 9c91 4284 A3ae Feb2bacbcba4alberto cabelloNo ratings yet

- Haematological Malignancies: Dr. Maruf Bin Habib Associate Professor of Medicine UamcDocument54 pagesHaematological Malignancies: Dr. Maruf Bin Habib Associate Professor of Medicine UamcSaifSeddikiNo ratings yet

- Therapy 2 ch4Document74 pagesTherapy 2 ch4Emad MustafaNo ratings yet

- Lymphoma in ChildrenDocument42 pagesLymphoma in ChildrenPriyaNo ratings yet

- Leukemia: Dr. C.REVATHI, M.SC (N) ., Ph.D. (N) ., Principal, Manjari Devi School & College of Nursing Bhubaneswar, OdishaDocument31 pagesLeukemia: Dr. C.REVATHI, M.SC (N) ., Ph.D. (N) ., Principal, Manjari Devi School & College of Nursing Bhubaneswar, OdishaHarshabardhan sahu100% (1)

- Hodgkin LymphomaDocument34 pagesHodgkin Lymphomaroohi khanNo ratings yet

- Hodgkin Lymphoma 1Document26 pagesHodgkin Lymphoma 1api-391376321No ratings yet

- TMP C0 BADocument12 pagesTMP C0 BAFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Hiperspenisme 2Document6 pagesHiperspenisme 2anakfkubNo ratings yet

- TMP 69 E9Document7 pagesTMP 69 E9FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Referat Lymphadenopathy NugrahaDocument13 pagesReferat Lymphadenopathy NugrahaNugraha WirawanNo ratings yet

- חומר לימודי קריפטוקוקוסDocument19 pagesחומר לימודי קריפטוקוקוסShani DavidianNo ratings yet

- Icu 2Document57 pagesIcu 2astewale tesfieNo ratings yet

- Human Immunodeficiency VirusDocument26 pagesHuman Immunodeficiency ViruspraneethasruthiNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis: Adventitial Sounds and Cervical LymphadenopathyDocument2 pagesTuberculosis: Adventitial Sounds and Cervical Lymphadenopathycaneman2014No ratings yet

- LeukemiaDocument51 pagesLeukemiaCres Padua QuinzonNo ratings yet

- Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Group 12Document14 pagesCrimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Group 12Arnold AyebaleNo ratings yet

- Radiology Case Report - Splenic AbscessDocument6 pagesRadiology Case Report - Splenic AbscessAbeebNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis and Chronic Renal FailureDocument38 pagesTuberculosis and Chronic Renal FailureGopal ChawlaNo ratings yet

- 39 BeljanDocument3 pages39 BeljanKelletCadilloBarruetoNo ratings yet

- Proceedings From The 2010 Annual Meeting of The American College of Physicians, Wisconsin ChapterDocument15 pagesProceedings From The 2010 Annual Meeting of The American College of Physicians, Wisconsin ChapterHarold FernandezNo ratings yet

- Lupus NephritisDocument33 pagesLupus NephritisNi MoNo ratings yet

- Howto Companion August2009Document4 pagesHowto Companion August2009lybrakissNo ratings yet

- 46-Year-Old Man With Fevers, Chills, and PancytopeniaDocument4 pages46-Year-Old Man With Fevers, Chills, and PancytopeniaDr Manoranjan MNo ratings yet

- 4B - Approach - To - Lymphadenopathy1234Document25 pages4B - Approach - To - Lymphadenopathy1234Omar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Caseating Granulomatous Inflammation 2Document15 pagesCaseating Granulomatous Inflammation 2Shambhu SinghNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Nephrotic SyndromeDocument42 pagesCase Study - Nephrotic Syndromefarmasi rsud cilincingNo ratings yet

- Case PresentationDocument19 pagesCase PresentationOmar SuleimanNo ratings yet

- An Etiological Reappraisal of Pancytopenia - LargestDocument9 pagesAn Etiological Reappraisal of Pancytopenia - LargestKaye Antonette AntioquiaNo ratings yet

- Cancer NursingDocument11 pagesCancer NursingFrancheskaNo ratings yet

- Neck Swellings - Reactive LymphadenitisDocument17 pagesNeck Swellings - Reactive LymphadenitisK'rtika SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Parasite Summary Table FinalDocument3 pagesParasite Summary Table FinalTamarah Yassin100% (1)

- Health Care Process As Applied To FamilyDocument39 pagesHealth Care Process As Applied To FamilyMarichelle Vicente- Delos Santos100% (3)

- AtsDocument3 pagesAtsIntanNirmalaNo ratings yet

- MEASLES IN CHILDREN in English Dr. Dinda Yuliasari FIXDocument8 pagesMEASLES IN CHILDREN in English Dr. Dinda Yuliasari FIXDinda yuliasariNo ratings yet

- SKDIDocument22 pagesSKDIFakhrunnisak UunNo ratings yet

- Liver Biopsy - H. Takahashi (Intech, 2011) WWDocument414 pagesLiver Biopsy - H. Takahashi (Intech, 2011) WWmientweg100% (1)

- Kalcker Parasite Protocol-K. Rivera 2014 Book PDFDocument80 pagesKalcker Parasite Protocol-K. Rivera 2014 Book PDFanarozi100% (3)

- Rickettsial InfectionsDocument45 pagesRickettsial InfectionsTarikNo ratings yet

- Pathogen Safety Data Sheet: Candida AlbicansDocument1 pagePathogen Safety Data Sheet: Candida AlbicansDila AngelikaNo ratings yet

- Presence of Enterobius Vermicularis Ova On The Fingernails and Risk Factors of Its Infection Among Schoolchildren Aged 6-9 Years in Cabili Elementary SchoolDocument11 pagesPresence of Enterobius Vermicularis Ova On The Fingernails and Risk Factors of Its Infection Among Schoolchildren Aged 6-9 Years in Cabili Elementary SchoolMartin ClydeNo ratings yet

- Phylum Aschelminthes - FormattedDocument30 pagesPhylum Aschelminthes - FormattedkingNo ratings yet

- Chapter 27aDocument228 pagesChapter 27aMiaNo ratings yet

- RJ 14Document6 pagesRJ 14Lujille Anne TalanquinesNo ratings yet

- Radiation TherapyDocument9 pagesRadiation TherapyNica PinedaNo ratings yet

- Safe Entry Contactless Symptom Detector For CovidDocument60 pagesSafe Entry Contactless Symptom Detector For CovidSujit GangurdeNo ratings yet

- FORUMDocument4 pagesFORUMGan Jia JingNo ratings yet

- Dermatologija Atlas U BojiDocument564 pagesDermatologija Atlas U BojiArmen Meskic67% (3)

- Endocrinology HandbookDocument75 pagesEndocrinology Handbookhirsi200518No ratings yet

- Lecture-Biopesticides (Compatibility Mode) PDFDocument44 pagesLecture-Biopesticides (Compatibility Mode) PDFARIJITBANIK36100% (1)

- Laboratory Test Report: Test Name Result Sars-Cov-2Document1 pageLaboratory Test Report: Test Name Result Sars-Cov-2Karthikeya MoorthyNo ratings yet

- Wsedrftghdfghx FGDFGHWJK FGHXCVBDocument2 pagesWsedrftghdfghx FGDFGHWJK FGHXCVBJay PeeNo ratings yet

- Paeds McqsDocument4 pagesPaeds McqsSidra JavedNo ratings yet

- Guias Infecciones Intraabdominales IdsaDocument32 pagesGuias Infecciones Intraabdominales IdsaSylvain ColluraNo ratings yet

- SummativeDocument2 pagesSummativeReyna Flor MeregildoNo ratings yet

- Paracytology Chart SummeryDocument15 pagesParacytology Chart SummeryOnSolomonNo ratings yet

- Patent US20120251502 - Human Ebola Virus Species and Compositions and Methods Thereof - Google PatenteDocument32 pagesPatent US20120251502 - Human Ebola Virus Species and Compositions and Methods Thereof - Google PatenteSimona von BrownNo ratings yet

- Bio-Vision - SSLC Biology em Sample QN 2019Document12 pagesBio-Vision - SSLC Biology em Sample QN 2019anandkrishnaNo ratings yet

- The Life Cycle & The Transmission Dynamic Versi 1Document14 pagesThe Life Cycle & The Transmission Dynamic Versi 1rayNo ratings yet

- Gene Therapy - Promises, Problems and ProspectsDocument4 pagesGene Therapy - Promises, Problems and ProspectsLordsam B. ListonNo ratings yet

- What Is The CervixDocument13 pagesWhat Is The CervixAgusdian Rodianingsih100% (1)